| 6 | Lone Wolf Georg Elser and the Bomb in the Beerhall |

Like many of those who would come to resist Hitler, including Claus von Stauffenberg, Johann Georg Elser was a Swabian, a native of the sleepy, south-west corner of Germany that was a region of thrift, independence and sturdily liberal political traditions. Born in January 1903 into a family of lumberjacks, smallholders and millers, Elser shared the childhood burdens of his future intended victim, Hitler, having a loving mother yet suffering a violent, drunken father, Ludwig Elser. The eldest of five children from a Protestant family, Elser grew up a slight, wiry, thin-faced loner. Fun did not enter his world, and when he was not helping his mother care for his younger siblings, he was put to work early slaving for his father, whose almost nightly beatings produced a burning sense of injustice in the boy Georg, and a corresponding burning desire to right the wrongs of a profoundly unjust universe.

Elser graduated from his secondary school in 1917, and lost no time in distancing himself from his father’s failing haulage business and taking up an apprenticeship in a foundry. But the hot, heavy work was uncongenial to the delicate boy, who always preferred his own company. He secured another apprenticeship, with a cabinet-maker, where he honed his skills at carpentry. A patient perfectionist by nature, young Elser was ideally suited to the long hours and delicate, laborious work demanded in working wood. But, although his woodworking skills became increasingly prized by a succession of employers, Elser’s world was a profoundly isolated one. Lacking even ordinary social skills, he had no friends and few contacts of any kind outside his family and his shifting workplaces. Forming a relationship was a high hurdle for the tongue-tied loner, and, according to his Gestapo interrogators, he was still a virgin at twenty-five who did not even know how to masturbate.

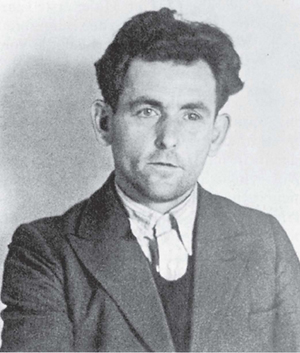

Georg Elser.

Elser was one of the millions of victims of the Wall Street Crash of October 1929. Jobs – he had worked as a clock-maker, watchmaker and as an ordinary carpenter – dried up, and he was forced to return to his parental home in the village of Hermaringen. A late starter, only now did Elser begin to develop sexual and political interests. Making up for lost time, he formed several relationships in quick succession, the first with a woman named Brunhilde from Konstanze on the Bodensee, then – as he confessed to his Gestapo tormentors – with ‘a certain Anna’ and finally with ‘Mathilde N’, ‘Hausfrau H’ and ‘Hilda N’. Despite an attempt to procure a Swiss abortion, Hilda bore Elser an unwanted son, Manfred, a child whom he was obliged to support financially, although Elser and Hilda did not live together; his payments were often either paid late or not at all. Elser, the embittered loner, would never make a contented family man, and after his father’s business finally failed he left home for the last time and resumed his lonely existence as a wandering chisel for hire, while living in a succession of rented rooms.

Elser’s revolt against the usual Swabian template of comfortable, conformist life extended to his politics. Although never a party member, he was briefly affiliated to the Communist Party’s paramilitary arm, the Red Front Fighting League, and he voted Communist at every election until the party was banned after the Nazis came to power in 1933. Although no Marxist, he regarded the KPD as the party of the working man, and believed that the pay and conditions of the working class had deteriorated sharply since Hitler had become chancellor. As an itinerant worker, he resented the increasing dragooning of the working class into state-run enterprises and, although not a religious man, he also resisted the implicit Nazi claim to replace the Christian religion with a sort of cod German paganism. Finally, Hitler’s rearmament programme and his aggressive foreign policy had not escaped Elser’s notice. He believed that the Führer was firmly set on a path to war and that he must be stopped. He was not afraid of demonstrating his hostility in public; once he ostentatiously turned his back, whistling and refusing to join the crowds giving the Hitler salute during a Nazi street parade. Such gestures could have dangerous consequences as the party tightened its grip on Germany, but Elser never lacked courage – or stubbornness. Then, in November 1938 in the wake of the Munich crisis that had brought the world to the brink of war, came the next logical step in his thought processes: if no one else was prepared to stop Hitler, then he, Georg Elser, the nobody from Hermaringen, would do the job.

On 8 November 1938, Elser took a train for Munich. His self-imposed mission in the ‘party capital’ was to closely observe the annual Nazi commemoration of the failed 1923 Beerhall putsch, Hitler’s premature attempt to seize power by naked force. The ceremonies celebrating this bloody fiasco every autumn had been elevated by the Nazis to the status of a quasi-religious cult. The increasingly portly party leaders squeezed with difficulty into their original Brownshirt uniforms and solemnly re-enacted their march through Munich’s streets until they reached the Odeonplatz, the central square where a ragged volley from a police cordon had scattered the Nazis like autumn leaves, leaving fourteen of them dead (two more putschists were killed elsewhere). Hitler, Goering, Himmler, Hess and other Nazi leaders who had taken part in the putsch appeared publicly, regular as clockwork, each 9 November to rally the faithful, pay tribute at the tombs of their sixteen fallen comrades, and re-dedicate one of the party’s founding myths.

This year, Georg Elser was also on hand to view the proceedings. On the evening of 8 November he wandered into the Bürgerbräukeller, the vast beerhall where Hitler had launched his putsch by hijacking a meeting addressed by Bavaria’s conservative leaders. This event was marked each year by the Führer giving a speech to his ‘Old Fighters’ at the same location. After Hitler had finished this year’s oration, Elser entered the beerhall and surveyed the scene with a practised eye as workmen began to take down the flags and bunting, and dirndl-clad waitresses lifted the heavy beer steins and swabbed down the long trestle tables. Here, Elser decided, was the ideal place to eliminate Hitler, either with a pistol – had not Hitler himself fired his handgun into the beerhall ceiling as the starting signal for his putsch? – or, more ambitiously, with a bomb.

The more Elser saw of the Bürgerbräukeller – and he visited it repeatedly over the next three days, making his modest stein last for hours as he eyed up the internal fittings and architecture – the more he liked what he saw. Virtually uniquely in the German calendar, he knew, twelve months in advance, exactly where Hitler would be standing a year hence. There was the speaker’s lectern he always used, ideally positioned against a stout pillar. As Elser confessed to his Gestapo interrogators later:

The idea slowly began to form in my mind that the best way to do it was by packing high explosive into the pillar behind the rostrum . . . some gadget would have to be found that would set the explosive off at the right moment. I picked the pillar because chunks of masonry from the explosion would hit the speaker and with a bit of luck the weakened roof might fall on him too.

Unbeknownst to Elser, he was not the only potential assassin at large in Munich that November with the Führer as his target. Swiss-born, French-speaking Maurice Bavaud was also a loner, but one with a very different background to the impoverished Elser. A pious Catholic, with a fervently moral standpoint, during the course of intensive discussions with his fellow students at a theological seminary in Brittany, Bavaud had become convinced that Hitler was the Antichrist and that it was his bounden duty to kill him. Learning German at his home in Neufchâtel in the summer holidays of 1938, Bavaud travelled to Germany and began a long series of fruitless attempts to gain access to Hitler. Procuring a pistol and ammunition in Berlin, Bavaud went to Hitler’s mountain retreat at Berchtesgaden, where he practised his marksmanship in the woods and repeatedly tried to secure an interview with the Führer, even going to the lengths of forging fawning letters from French Fascist leaders in an attempt to smooth his path to Hitler’s side.

Learning that his best chance of getting a clear shot at Hitler would be at the annual Beerhall putsch commemoration that November, Bavaud made his way to the Bavarian capital where he, like Elser, haunted the streets in the hope of getting a clear view of his target. He managed to get a grandstand seat in the front rank of spectators as the Nazi leaders’ parade approached, but just as he was about to pull out his pistol and fire, a forest of right arms shot up in the Hitler salute, blocking the young Swiss’s view completely. When the arms fell, Hitler had moved on, and Bavaud’s last chance of killing the ‘Antichrist’ had vanished. He made one last frantic attempt to break through the security cordon protecting Hitler at Berchtesgaden, but when that failed, Bavaud’s money ran out too, and he jumped on a train for Paris. Apprehended by a ticket inspector, his luggage was searched and his pistol discovered. Passed to the Gestapo, he was soon forced to reveal the details of his stalking of Hitler and he was sentenced to death by guillotine, a penalty that was eventually carried out on 14 May 1941, in Berlin’s Plötzensee Prison – the same grim jail where the July plotters would also meet their agonising ends.

On receiving the Gestapo report of their investigation of Bavaud’s abortive attempt on his life, Hitler remarked fatalistically that he was not surprised that 90 per cent of history’s assassination attempts had been successful. If an assassin was fanatically prepared to sacrifice their own life in taking their target’s life, said Hitler, then no security precautions on earth could stop them. The only effective way of lessening the chances of a successful assassination, the Führer opined, was by varying one’s routine and changing plans at the last minute. Although Hitler reputedly had his cap lined with metal and reportedly even kept a parachute strapped beneath his seat whenever he flew, it was only just such a variation that would save his life yet again from a second stalker in Munich.

With the time slowly ticking down to his self-imposed deadline of November 1939, Georg Elser began to prepare his own time bomb. His first move was to steal a fuse and 250 grains of gunpowder from his current employer, who was, conveniently enough, a munitions manufacturer in the small town of Heidenheim. In April 1939 he made a second visit to Munich to reconnoitre the location for his assassination attempt. Realising that he needed more sophisticated materials to fashion his bomb, he took a labourer’s job at a quarry, the Steinbruck Georg V in the nearby town of Köningsbronn, where it was a comparatively easy task to steal explosives and a detonator from the carelessly guarded site store. Ever the lonely autodidact, Elser taught himself how to construct the bomb, toiling for long hours in his workshop and telling curious enquirers that he was inventing a new type of alarm clock. He learned how to handle explosives, and tested the result by letting off small charges in the fields around his home. After Hitler occupied the rump of Czechoslovakia in March 1939, Elser, more certain than ever that the Nazis were set on launching a new war on the world, returned to Munich to finesse his plans by taking measurements and making detailed sketches of the Bürgerbräukeller’s interior. He even attempted – unsuccessfully – to get a job waiting tables at the beerhall. But, having failed in that, he resolved, undaunted, to gain access by more devious means.

At the beginning of August 1939, as the catalyst for the Second World War, Poland, began to bubble ominously, Elser gave up his job at the quarry and returned once more to Munich. He took with him his heavy tool chest; beside the usual tools of his trade – saws, hammers, chisels, files and planes – the wooden chest now contained, secreted in a hidden compartment, the illicit materials he had been working on over the previous nine months: including fifty kilograms of high-explosive sticks, detonators, wire, a battery and six clock movements with which he intended to fashion his infernal device. Like any good German, Elser reported his presence in Munich to the municipal police – then, as now, an obligatory requirement of all citizens – rented a room, and began work on his final preparations.

He followed an unvarying routine: every evening he would attend the Bürgerbräukeller, arriving around 9 p.m. A small, insignificant figure, Elser never attracted much attention at the best of times, but in the crowded, beery, raucous and smoke-filled atmosphere of the vast beerhall, sandwiched between bulky Bavarians bursting out of their lederhosen, the diminutive Swabian carpenter was almost lost to sight as he quietly sipped his beer, munched his sausage sandwich and waited for closing time. His nondescript presence became such a customary event, that the waitresses and bar staff got used to him and ceased to notice Elser altogether. He had, as he had hoped, become the invisible man: almost literally part of the beerhall’s furniture.

Around 10 p.m., regular as clockwork, Elser would finish his modest meal, wipe his lips, and casually climb the stairs to a deserted cloakroom, carrying his toolbag like any home-going worker relieving himself of the night’s intake of Bavarian beer. Here he would hide while the Bürgerbräukeller staff closed its doors, cleaned up and went home. On the first night he waited silently in the darkness for another hour to check that there was no night watchman apart from the Bürgerbräukeller cats. Then he stole silently out and got to work. For the first three nights he used a fretsaw carefully to saw out a rectangular panel in the wooden cladding casing the brick pillar. Then he fitted tiny hinges to his homemade ‘door’ so it could easily be levered open, allowing him to attack the stonework beneath.

Working by the shaded light of a torch, pausing frequently to strain his ears for any disturbing visitors, he laboured for weeks, chipping out the mortar and prising the bricks from the pillar to create his bomb-holding cavity, night after endless night. Progress was agonisingly slow. Each rasp of his hand drill, each hammer blow, echoed monstrously loud in the eerie silence of the cavernous hall. He learned to time each blow of the hammer on the metal chisel’s head to coincide with masking extraneous sounds, such as the passing of a tram, or the automatic flushing of the beerhall toilets. This made the work so slow and drawn out that Elser began to worry that his meagre and carefully hoarded funds would run out before the job was done. After his night’s sawing and chipping, in the early hours he would meticulously collect every scrap of sawdust, every splinter of brickwork and every particle of dirt, so that no trace remained of his nocturnal labours. Above all he ensured that the door to the cavity he was hacking out fitted flush and snug with the rest of the wooden cladding. Invisible even to his eye, it would have to pass the minute inspection carried out by the Nazi security men on the eve of Hitler’s speech.

Once he was satisfied that all trace of his presence had been removed, Elser would tiptoe back to his hiding place in the cloakroom and wait for the arrival of the beerhall’s staff to open up and welcome the first of the day’s customers – bleary-eyed early risers coming in for a fortifying slug of schnapps to ward off the chill of the early Munich winter. Cautiously, Elser would emerge from his hiding place, mingle briefly with the morning drinkers, then head back to his lodgings like the shift worker he was, for a much-needed daytime sleep.

He left the most intricate and dangerous part of his task to the last: priming the bomb itself. His aim was to be well clear of the beerhall by the time his months of back-breaking and dangerous toil climaxed in the huge explosion that he hoped would remove Hitler forever. Indeed, if his scheme worked out, he would not be in Munich at all – nor even in Germany. Elser’s getaway plan called for him to be miles away, in the safety of Switzerland, by the time the bomb went off. Using the clock workings he had collected from his days as a watchmaker, he constructed a long-set timer that would run for up to 144 hours before activating a lever that in turn triggered an elaborate system of springs, weights and shuttles. The end result was a steel-tipped prong that would strike a live rifle cartridge embedded in the explosive. The meticulous Elser even added an identical second system in case the first one failed. The time bomb was enclosed in a wooden clock case that he had lined with cork to muffle the telltale ticking of the clock. For the final touch, he inserted a sheet of tinplate on the inside of his wooden door so that the cavity would not sound hollow if knocked by a nosy security snoop.

By the beginning of November, with perfect timing, all was ready. On 2 November 1939 Elser again visited the beerhall that had become his home from home and safely installed his bomb. Three nights later, on 5 November, he set the timer to explode at exactly 9.20 p.m. on the evening of 8 November – right in the middle, as he hoped, of Hitler’s speech. Finally, on 7 November, after visiting his sister, and borrowing thirty marks from her to buy his train ticket to the Swiss frontier, he returned to the Bürgerbräukeller for the last time to make a final check that the timing device was still running. It was. Nothing, he calculated, could now prevent his device, so laboriously prepared and carefully concealed, from interrupting Hitler’s annual address to the party faithful with what he hoped would be fatal consequences. After paying a farewell visit to his Munich lodgings, he bought a third-class ticket at Munich’s Hauptbahnhof for the town of Konstanze on the border, a place he knew from his brief affair there with Brunhilde. As his train, dimly lit with the blue lamps of the blackout, gathered speed in the night, Elser allowed himself to relax. The Führer’s fate was fixed.

Hitler flew into Munich airport on the afternoon of 8 November 1939. For once, the dictator was distracted, with his mind not completely on the coming commemoration. His thoughts, rather, were on the war that he had launched just two months before. The day before his flight to Munich he had reluctantly rescinded his order for a surprise attack on France and the Low Countries to be launched on 12 November after receiving persistently unfavourable weather reports forecasting rain and fog for the foreseeable future. Determined to press the attack home, if at all possible, Hitler, in a foul and frustrated temper, had ordered a review of the weather situation on 9 November. That urgent business would call him back to Berlin rather earlier than usual – this year’s elaborate parades and ceremonies would be curtailed, and the exigencies of wartime would be blamed.

He had seen the bad weather for himself during his flight south. So thick was the fog that his pilot, Hans Bauer, recommended that he return to the capital not by air, but in his armoured train ‘Amerika’. That would mean a departure even earlier than anticipated. Hitler ordered that his address to the ‘Old Fighters’ in the beerhall should be brought forward by one hour – crucially, he would now begin speaking at 8 p.m. rather than at 9.

There was one piece of very personal business that Hitler attended to before duty called at the Bürgerbräukeller. He went to the hospital bedside of Unity Mitford, the half-demented English society girl who had fallen for him in a major way after stalking him at his favourite Munich restaurant, the Osteria Bavaria. With her china-doll blue eyes, blonde Aryan looks, her minor aristocratic connections and her evident dumb adoration, Unity appealed to Hitler, and he admitted her to his circle of hangers-on. In time, Unity introduced other members of her eccentric family to Hitler – including her sister Diana, who shared her sister’s Fascist sympathies and eventually, in October 1936, married her lover, British Fascist leader Sir Oswald Mosley, in Berlin with Hitler and Goebbels as guests of honour. Mortified by the outbreak of war between her British homeland and her adopted Fatherland, Unity shot herself in the Munich park appropriately called The English Garden, on 3 September 1939 – the day Britain declared war on Germany. She botched the job and the bullet lodged in the back of her head.

Hitler placed his admirer – who really was a dumb blonde now, since the shot had rendered her speechless – in an expensive private clinic on Munich’s Nussbaumstrasse and paid for her care under Professor Magnus, Germany’s leading brain surgeon. But the bullet was too deeply lodged to remove and Unity lay for day after day, semi-comatose. Hitler stopped by, left a bouquet of flowers and gave orders for Unity to be sent back to England via neutral Switzerland as soon as she was fit enough to make the journey. Then he was driven to the Bürgerbräukeller where, in the back rooms where he had held Bavaria’s ruling triumvirate hostage at the launch of the putsch in 1923, he made the final preparations for his speech.

He changed into a fresh uniform, with newly laundered silk underwear laid out by his valet Heinz Linge, gargled with glycerine and warm water to ease his throat, and began to psych himself up to meet his public. Already he could hear the hubbub of the growing throng gathering in the main hall where Elser’s bomb ticked on unheeded. Had Elser but known it, he need not have made the meticulous security arrangements to cover up his deadly handiwork, since the Nazis’ own security in the hall was cursory to the point of negligence. After a spat between Munich’s town police and the city council over responsibility for the historic hall’s security in 1936, Hitler had given a judgment of Solomon that the party itself should look after security. This was a mistake: the sharp attention to danger of the ageing Old Fighters had atrophied and grown as blurred as their beer-sodden senses and as bloated as their swelling bellies. As a result, no search of the premises had been carried out before Hitler’s address, and security on the night rested with a single guard, a former Munich police officer who had been drafted into the army, one Josef Gerum.

As usual, on this November night, the hall was packed. Three thousand beefy, beer-swilling Brownshirts were squeezed along the narrow benches in front of the trestle tables. As the band struck up the military tune, the ‘Badenweiler Marsch’, all eyes turned to a solitary figure who had marched into the room, bearing aloft the party’s most sacred icon – the Blut Fahne or Blood Banner. This was the flag that had flown at the head of the Nazi marchers during the original putsch, and had been stained with the blood of the party’s fallen martyrs. This year and every year, the flag – used by Hitler to ‘touch’ every subsequent party flag with its sacred aura – was borne in by the whip-thin Old Fighter Josef Grimminger, an expressionless Hitler look-alike with the same toothbrush moustache, chosen for this signal honour because of his fanatical loyalty to the Führer.

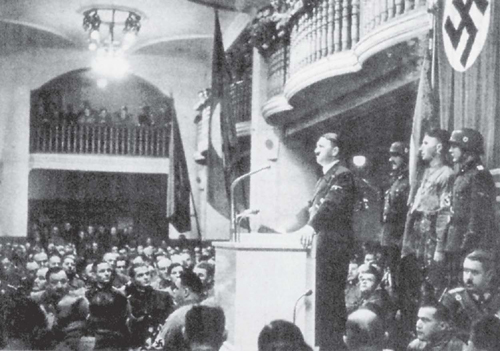

Hitler speaking at Bürgerbräukeller, 8 November 1939.

Grimminger was closely followed by Hitler himself, processing slowly down the central aisle between the tables as the faithful rose to their feet and roared their ‘Heil!’ from well-oiled throats. Hitler spoke for almost an hour, delivering an impassioned attack on England, claiming that as Britain had declared war back in September, it was they and not he – in particular the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill – who were the warmongers. However, he was ready to fight such a war, he warned in an uncompromising message designed to stiffen the sinews of his people before the coming offensive in the west. Then, suddenly, almost abruptly, it was over. Just after 9 p.m., Hitler stopped speaking and left the hall, heading for his train – according to Party Secretary Martin Bormann’s diary – at 9.07 precisely. Just eighteen minutes after the Führer had left the hall, at 9.20 p.m., right on schedule, Elser’s bomb exploded.

Hitler’s sudden departure had left the Brownshirts, despite their inebriated condition, somewhat deflated. Drunk on Bavarian beer and the stream of Hitler’s impassioned words, they had cheered and roared their approval of his hard, slashing rhetoric, and when he abruptly left, there was a certain sense of letdown: Hamlet had departed and the drama was over. Quite quickly, in small groups and singly, the faithful trailed out and the hall began to empty. Within ten minutes, barely one hundred people remained: some were Nazis, disconsolately emptying the dregs of their beer, while others were musicians packing up their instruments and bar staff clearing up the detritus left behind after the rally.

Then Elser’s bomb tore the night – and the hall – apart. What witnesses described as a blinding flash of violet light like a lightning strike streaked across the huge hall, accompanied by an ear-splitting blast. The device had all the devastating effect that Elser had hoped for, and more: it shattered the pillar in which it had been concealed, bringing the gallery it supported crashing down. The blast blew out doors and windows and smashed chairs, tables – and people – to fragments. Had Hitler still been standing on the rostrum he had just vacated he would have been instantly killed. As it was, three of his Old Fighters lay dead, while five more were dying, along with a waitress; sixty-three other people were injured – sixteen of them seriously. Shocked survivors, covered with dust and debris, their ears ringing, struggled out through a fog of smoke into the cold night air.

An interior view of the Bürgerbräukeller showing the devastation caused by Elser’s bomb. The explosion killed eight people and injured more than sixty others.

Half an hour before the blast, two German border guards in the lakeside frontier town of Konstanz were making their customary routine patrol along the tall barbed-wire fence separating Germany from Switzerland. Bored, they paused in a garden to listen to a live radio relay of Hitler’s beerhall speech, when one of them noticed a movement in the bushes nearby. Unslinging their rifles, they arrested the diminutive Elser, who could give no satisfactory explanation for his presence. Taken to the Kreuzlinger Tor border post, he was ordered to empty his pockets. Their damning contents included a membership card from the banned Communist Red Front paramilitary wing, to which he had once briefly belonged. Along with this were other telltale pieces of evidence linking him with the enormity that was about to erupt at the Bürgerbräukeller. They included a postcard of the beerhall and instructions on manufacturing munitions. As if such clues were not enough for even the dimmest police official to start to entertain suspicions, Elser was also carrying a number of screws and pieces of metal, which he lamely maintained were necessary for his profession of clockmaker. One of his captors, an ex-soldier, was not to be so easily fooled: ‘You cannot make a clock with those!’ he exclaimed, ‘They are for making detonators.’

At his confession to the German police, Elser sketching out from memory the preparation for his attempt on Hitler’s life.

So careless was Elser’s conduct that night – he had made no effort to run away or escape – and so suspect were the clues he was carrying, that some historians long believed that he was a mere tool of some nefarious state conspiracy, concocted by the SS or Gestapo, who had manipulated or somehow induced Elser to make and plant his bomb. Was the whole plot, then, an inside job? Several factors make this unlikely – not least the appalling risk to the Führer and other leading Nazis if the bomb had malfunctioned and exploded prematurely. Instead, most historians now accept the simplest and most obvious truth: Elser was exactly what he said he was. He was a most unusual assassin, in that he worked alone and entirely without outside support, except for the small sum borrowed from his sister for his rail fare. He was, nevertheless, a very determined and ingenious assassin, and one whose bomb came nearer to killing Hitler than any other attempt – with the single exception of Stauffenberg’s bomb.

The question then arises: why did Elser, this most meticulous and cautious of men, carry such obvious clues around with such wild abandon? Why, having got so far – and having succeeded in carrying out his scheme and come close to getting clean away with it – did he fall at this final, fatal hurdle when he was within sight of Switzerland and safety? The answers can only be conjecture: human psychology is so complex that a person who is infinitely painstaking in some areas can be careless to the point of negligence in others. The self-imposed strain that Elser had been under for months may have sapped his last reserves of calculation and made him throw caution to the winds. Having only known Konstanz in peacetime, he may have reckoned on the relatively lax border controls of pre-war days, forgetting that Germany was now at war and open to infiltration from its neutral neighbours, and that border controls were correspondingly stringent. He may well have deliberately carried the mementoes of his deadly deed as evidence to present to the Swiss authorities or opposition groups that he was presumably hoping to meet in Switzerland to show that he, Georg Elser, ex-nobody, was the lone bomber who had rid the world of Hitler. That he was a somebody now; that, after years of obscurity, he was a genuine hero.

At any rate, even before news of the bomb broke, the Konstanz Guards knew they had caught a suspicious character at the very least – a Communist, a liar, very possibly a terrorist. He was handed over to the tender mercies of the Gestapo.

The news of the bomb reached Hitler at Nuremberg, where his train was stopped and he was informed of the devastating attack by the local police chief. He rang Bavarian Gauleiter Adolf Wagner, who had taken charge of the investigation on the spot and demanded that the culprits be caught, and fast. Himmler was already on the case with his usual zeal. The entire surviving staff of the Bürgerbräukeller were arrested, and an enormous reward of 600,000 Reichsmarks was offered for the detention of those responsible. By the early hours of 9 November, no fewer than 120 suspects – one of them Elser – were under arrest. Himmler fell in with his master’s immediate assumption that the deadly English Secret Service were behind the bomb plot. The Nazi leaders, especially Hitler, Himmler and Heydrich, all had an exaggerated fear and respect for the wily machinations of SIS/MI6, and to an extent based their own covert operations on the supposed style of the British. (Heydrich even signed himself ‘C’ in green ink in imitation of his British counterpart.)

To Hitler and the SS overlord the beerhall bomb bore all the hallmarks of the treacherous foe, and they would spare no effort in finding links. As luck would have it, they had the ideal instruments immediately to hand. For some weeks one of Himmler’s most trusted henchmen, the former lawyer Walther Schellenberg, had been holding talks in Holland with the chief of Britain’s SIS station in the Netherlands, Major Richard Stevens, and Captain Sigismund Payne-Best, a long-time Dutch resident and veteran intelligence officer from the First World War. Payne-Best was the Dutch head of a secret section of MI6, the ‘Z’ section, which shadowed the ‘official’ secret service throughout Europe. Schellenberg had got in touch with the two British agents through a double-agent, Dr Fischer, who had claimed to represent a high-ranking clique of anti-Nazi German officers plotting to remove Hitler from power.

A series of meetings took place in the autumn of 1939 at which Schellenberg represented himself as one ‘Captain Schaemmel’, a liasion man for the anti-Hitler clique in the Wehrmacht. Schellenberg was, in fact, a major in the SS and Reinhard Heydrich’s chief of counterintelligence in the SS’s security service, the Sicherheitdienst (SD). In London, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain had been kept personally informed of these ‘negotiations’ and had authorised full British support for a military putsch against Hitler that would end the war and lead to a new British–German alliance against Stalin’s Russia. It was a typical intelligence game of double bluff, in which Schellenberg was playing the long game, presumably hoping to extract evidence of Britain’s wartime intentions and its post-war plans, while at the same time compromising Britain diplomatically, undermining its stated war aims and finding out as much as he could about the country’s legendary intelligence services.

Following his narrow escape, Hitler, jumping to the conclusion that the long arm of Britain’s secret service had been behind Elser’s bomb, ordered that Schellenberg’s game be brought to an abrupt and typically violent conclusion. At the next scheduled meeting – which had already been arranged for 9 November – the two Britons were to be seized, and, in blatant violation of the Netherlands’ neutrality, abducted across the border and interrogated in depth and at the SD’s leisure in Germany.

Another of Heydrich’s most trusted men was placed in charge of the kidnap. But Alfred Naujocks was an altogether more thuggish character than the intellectual Schellenberg. He was the man who had been entrusted with the job of staging the ‘Gleiwitz incident’ – the mocked-up attack on a German radio station on the Polish–German frontier that had been one of Hitler’s excuses for attacking Poland in August 1939, thus triggering the Second World War. In this coup, Naujocks had left the corpses of murdered concentration camp inmates, dressed in Polish uniforms, strewn outside the radio station in a flimsy effort to suggest that Poland had attacked Germany. Now, ‘the man who started the war’ was to be entrusted with staging another ‘incident’ on another border.

As soon as Stevens and Payne-Best, along with their Dutch military minder, Major Dirk Klop, arrived at the small town of Venlo, very close to the Dutch border with Germany, Naujocks’s plan was activated. Two high-speed Mercedes limousines, filled with a dozen burly SS men, were driven through the frontier and, after a brief gun battle that ended with Major Klop being shot dead, the two startled Britons were seized and rushed back into Germany. The whole thing was over in a couple of minutes. Astonishingly, the inexperienced Stevens was found to be carrying – uncoded – a list of SIS’s agents throughout Europe.

Alfred Naujocks: ‘the man who started the Second World War’.

The ‘intensive interrogations’ that the pair were about to undergo were hardly necessary: Himmler and Heydrich already had a virtually complete picture of the structure of British Intelligence on the European continent. What they did not have – and never would possess – was indisputable evidence connecting British intelligence with Georg Elser and his bomb. Despite being subjected to the most gruesome tortures that the Gestapo could devise, including a beating personally administered by Himmler himself, and despite successfully building a complete replica of the bomb that he had designed at his captors’ invitation, Elser never furnished evidence of the grand conspiracy that Hitler insisted lay behind the attempt on his life. This was not because Elser did not want to – like any torture victim, he would have said or done anything to end his torment – but because he could not. No such evidence ever existed.

Café Backus on the Dutch–German Frontier near Venlo, where the SS team shot Major Klop dead and arrested Stevens and Payne-Best. Major Dirk Klop.

This did not, of course, prevent Goebbels’s propaganda machine from going into overdrive in a frenzied denunciation of the hidden hand of British intelligence that, it trumpeted, lay behind the outrage at the Bürgerbräukeller. The convenient capture of the two SIS men at Venlo, and the death of Major Klop provided more grist to Goebbels’s mill: not only had two top agents of MI6/SIS been caught red-handed at their nefarious tricks, but the presence of the ill-fated Major Klop at their side was evidence that the Dutch were hand-in-glove with the British and that the neutrality of the Netherlands was a sham. Thus was another excuse provided for the coming attack on the West.

Elser’s bomb and the Venlo Incident, as the double abduction soon became known, had two long-term consequences, both equally malign, for the true conspirators in the Wehrmacht who, in contrast to Schellenberg’s sham, really were determined to put an end to Hitler’s regime. The first consequence was that it terminally prejudiced Whitehall – and Winston Churchill in particular – against holding any talks, secret or otherwise, with any Germans, no matter how anti-Nazi they were. This cordon sanitaire isolated the resistance and almost guaranteed its ultimate failure.

The first photographs released to the German press by the Gestapo, showing Georg Elser, Major R. H. Stevens and Captain S. Payne-Best. The linking of the three men implied that Stevens and Best had been involved in the Bürgerbräukeller attempt on Hitler’s life.

The second malign consequence for the conspirators who wanted to eliminate him was that Hitler’s security was dramatically tightened. The icily efficient Reinhard Heydrich decreed that the protection of the Führer’s life came before all other tasks, and took it upon himself to install a raft of reforms making the assassin’s job all but impossible: no one was allowed to carry a weapon in Hitler’s presence; a new beefed-up security detail would be on hand at all times and would be authorised to carry out spot checks and searches even on the most high ranking of visitors. No mail, parcels or even innocuous bouquets of flowers would any longer be presented to Hitler personally, or would be handled by him until they had been thoroughly examined by white-gloved SS guards.

Hitler himself was inclined to credit the power he called Providence for his lucky escape. He claimed, with increasing conviction, that he had left the Bürgerbräukeller early, not for the prosaic reason that he had a train to catch, but because an inner voice had been urging him to get out of the building as fast as he could. The fact that he had obeyed the voice and had thus saved his own life he interpreted as confirmation that he was Germany’s chosen man of destiny, divinely ordained to lead the Fatherland to undreamed-of heights of greatness. From now on all doubts were removed, all questions or cautions treated as akin to treason.

Guided and protected by Providence, Adolf Hitler prepared to lead Germany into the abyss.