| 9 | Valkyrie 20 July 1944 |

Even if Stauffenberg – like Christ himself – had his moment of fear and doubt before the Calvary that awaited him, his hesitation was only momentary. Having heard and accepted Tresckow’s stiffening message, he redoubled his efforts, and devoted his formidable energies to melding the disparate threads of the conspiracy finally into a workable plan. As ever, his major strength lay in his ability to multi-task, and he devoted almost as much time and thought to the political side of the plot as he did to its military aspects.

Though far from a leftist himself, Stauffenberg was adamant that any post-Hitler regime must be broadly based, extending from conservatives and nationalists on the right to Social Democrats and possibly even Communists on the left. He was very critical of the Reichswehr leaders under the Weimar Republic who, in opposing Bolshevism, had also set their faces against the moderate Socialists of the SPD, who represented a large proportion of the German electorate. In their rejection of the Social Democrats, Stauffenberg felt, the army commanders had opened the door to Hitler. Indeed, Stauffenberg respected many Social Democrats as being among the most principled and unwavering opponents of Hitler from the 1920s when many Germans – including himself – had been prepared to give the movement the benefit of the doubt.

Julius Leber.

One Social Democrat in particular who attracted Stauffenberg’s admiration and interest was Julius Leber, the former Reichstag deputy and the SPD’s spokesman on defence, who was (unusually for a party tinged by pacifism) a First World War army officer. Also unexpected in a nominally Marxist party Leber, like Stauffenberg, was a fervent Catholic. Introduced to Leber by Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenberg – the main middle man of the resistance, who had also put him in touch with von dem Bussche and Ewald von Kleist-Schmenzin – Stauffenberg soon marked him down as a likely future Chancellor of a post-war Germany, even though the ultra-conservative Goerdeler was the conspirators’ official choice for the post.

Ever since he had begun work at the Reserve Army in the Bendlerstrasse, Stauffenberg had been living in the leafy, wealthy Berlin suburb of Wannsee, ironically the scene of Heydrich’s notorious conference in 1942 which had given the green light for launching the Holocaust. Stauffenberg shared a large house at No. 8 Tristranstrasse with his brother Berthold and his uncle, Nikolaus von Üxküll – both seasoned members of the conspiracy. The house became the scene of hectic late-night meetings between the Stauffenbergs and surviving civilian conspirators, including Leber and his SPD and trade union colleagues Wilhelm Leuschner and Jakob Kaiser, Goerdeler, Yorck von Wartenburg and the theologian Eugen Gerstenmeier.

One of the main talking points was the political orientation of a future government. Stauffenberg, conscious of the need for popular, working-class support, urged Leber to take up the position of Chancellor. Leber, equally conscious of the disastrous post-1918 history, declined, saying he did not want a future Hitler to brand him a ‘November criminal’ who had presided over another government that had stabbed Germany’s soldiers in the back. Another point of angry discussion was the attitude of the conspirators towards Germany’s once-mighty Communist Party. Stauffenberg, as a Catholic aristocrat who had been involved in raising and equipping the anti-Communist ‘Vlasov Army’, composed of Soviet prisoners of war prepared to turn their coats and fight with the Germans against Stalin, naturally did not want to replace a dictatorship of the extreme right with one of the far left. He was scornful of Field Marshal Paulus and other senior officers captured by the Russians who had formed a so-called ‘Committee of Free German Officers’ under Soviet auspices, remarking: ‘I am betraying my government; they are betraying their country.’ Nonetheless, Stauffenberg did not wholly rule out German Communists playing some part in Germany’s future politics, and he even grasped at the straw that a Germany rid of Hitler could make a separate peace with Stalin’s Russia, after the repeated rebuffs the conspirators had suffered at the hands of the Western Allies.

* * *

On 21 June 1944 leading conspirators met at Yorck von Wartenburg’s home to thrash out the Communist issue, which had sharply divided them, with some plotters fiercely opposed to Communist participation in a future government while others – including Leber and Stauffenberg – argued for opening talks at least to explore what attitude the Communists would take towards a putsch. Despite violent opposition, the meeting reluctantly agreed to allow Leber to carry on with exploratory contacts with the Communist underground after he revealed that he had been invited the very next day to meet two Communist functionaries – Anton Saefkow and Franz Jacob – with whom he had shared a plank bed in a concentration camp in the early days of the Nazi regime.

On 22 June Leber, accompanied by Adolf Reichwein, a Socialist educationalist and former Kreisau Circle member, duly met Saefkow and Jacob in the Berlin flat of a Communist-sympathising doctor. Ominously, a third man was present: a stranger who, against all security rules, addressed Leber by his real name. Leber was instantly aware that the Communists had been infiltrated by the Gestapo, and that he was now a marked man. Although he did not turn up at the next scheduled meeting on 4 July, Reichwein did, and was duly arrested, along with Saefkow and Jacob. The following day, 5 July, Leber too was seized at his flat.

Stauffenberg’s efficient reports on the state of the Reserve Army had already drawn the attention and praise of Hitler himself, who is said to have remarked, ‘Finally, a General Staff officer with imagination and intelligence.’ For his part, Stauffenberg was considerably less impressed by the Führer. Their very first meeting took place on the afternoon of 7 June, the day after D-Day. Fromm and Stauffenberg had been summoned to the Berghof to report on the readiness of the Reserve Army, a question suddenly made less theoretical by the opening of the Second Front in Normandy. Also present were Goering, Himmler, Keitel and armaments minister Albert Speer. Afterwards Stauffenberg told his wife that Hitler had grasped his remaining hand between his two, which were badly shaking. During the meeting he had appeared abstracted, shuffling maps with his shaking hands, and all the while darting nervous, sidelong glances at Stauffenberg from his hooded eyes. Goering, Stauffenberg remarked with distaste, was clearly wearing make-up. All the Nazi leaders, he added, were ‘psychopaths’ and the atmosphere around them was poisonous and rotten, making it hard to breathe. The only man present who appeared even vaguely normal, he concluded, was Speer.

Stauffenberg made these remarks to Nina during the last weekend he would spend with his family, 24 to 26 June, at their townhouse in Bamberg. Countess Stauffenberg was full of her plans to take the children with her to their Schloss at Lautlingen – Stauffenberg’s own childhood country home – for their annual summer holidays. She was looking forward to the break more than usual this year. In the peaceful rural environment at Lautlingen it was still just possible to forget that there was a war on. Even in the small city of Bamberg there were constant air-raid alarms, and the elder Stauffenberg children had completed their end of summer term tests in underground shelters. Stauffenberg was strangely unenthusiastic about his family’s holiday plans. Later, in hindsight, Nina realised that he was worried about them being stranded in such a remote location in the aftermath of what he hoped would be his successful assassination of Hitler. Although Nina knew all about her husband’s growing revulsion with the regime – indeed she shared his views – she was unaware how deeply involved he was in plotting against Hitler’s life. Naturally, he wished to protect his family as far as possible from such dangerous knowledge and kept his intentions secret. When they parted she had no idea that she would never see her husband again.

On 1 July Stauffenberg was promoted to full colonel and officially confirmed as Chief of Staff to the commander of the Reserve Army, General Fromm. Taking Stauffenberg’s place as Obricht’s new aide was balding, bespectacled Colonel Albrecht Mertz von Quirnheim, Stauffenberg’s bosom friend and a committed conspirator. Stauffenberg’s new job meant that he would now be given regular access to the Führer at his daily military conferences. Of all the plotters, he – despite the handicap of his multiple injuries – would now be best placed to carry out an assassination attempt. He lost no time in doing so.

On 6 and 8 July, accompanied by his superior, General Fromm, Stauffenberg flew to Salzburg to brief Hitler once again at the Berghof, this time on the latest adjustments to the Valkyrie plan. Since the Normandy landings the High Command were increasingly worried that the Allies might attempt a landing on the almost unprotected north German coastline, and Stauffenberg was ordered to fine-tune Valkyrie to ensure that the 300,000 German soldiers who were at home on leave at any given time could be quickly assembled into scratch units called ‘shell detachments’ to meet any such incursion. Hitler approved his plan to give military commanders ‘executive powers’ in the event of an invasion, including authority over Nazi Party officials. Secretly, of course, such powers would mask the army takeover of the state that would follow the dictator’s elimination.

Before the second briefing, Stauffenberg saw his fellow conspirator General Stieff, the able little administrative genius who, despite his constant access to the Führer as chief of operations, lacked the great courage needed to attempt the assassination himself. Stauffenberg patted his soon-to-be notorious briefcase and told Stieff: ‘I have got the whole bag of tricks with me’ – a remark that Stieff interpreted as meaning that he was already carrying a bomb, rather than a heavy hint that Stieff should place the bomb himself. Stieff testified at his subsequent trial that he had dissuaded Stauffenberg from carrying out the attempt that day, though clearly, given the circumstances under which he made this statement, it must be questionable. At all events, and for whatever reason, no attempt was made on this occasion.

Back in Berlin, the pressure to act was becoming intolerable. Stauffenberg’s military duties included supervising the supply of reserve troops to the crumbling fronts, and he was well aware of the deteriorating, indeed hopeless situation, exacerbated by the ever-worsening Allied bombing raids. At the same time, the recent arrests of Leber and Rechwein – men who had become his friends, and about whose fate he felt personally responsible – weighed heavily on his mind and conscience. ‘We need Leber. I’ll get him out,’ he had told Adam von Trott zu Solz, one of the few civilian conspirators still at large. Stauffenberg’s aide-de-camp, Werner von Haeften, was telling people that his boss had ‘decided to do the job himself’ and Stauffenberg himself had incautiously told at least two people that he was engaged in high treason, and would be branded a traitor to Germany before history. What would be worse, however, he added, would be committing treason to his own conscience if he failed to act.

On 11 July Stauffenberg flew back to the Berghof for another afternoon briefing with Hitler. Once again, he was carrying the bomb in his briefcase. However, it had been impressed upon him by Beck and other military conspirators, that it was highly desirable that both Goering – slated to take over command of the Reich’s military forces in the event of Hitler’s death – and Himmler, whose growing SS would be the chief armed body to be overcome in any post-assassination standoff, should die with the Führer. When he arrived at the Berghof, Stieff, aware of the deadly burden the young colonel was carrying, and nervous as usual, informed him – possibly with relief – that neither Goering nor Himmler would be present. ‘Good God,’ Stauffenberg responded, ‘shouldn’t we go ahead anyway?’ Yet again, however, Stieff’s caution prevailed, and the assassination attempt was once more postponed.

That Stauffenberg was serious about making an attempt on this occasion is evidenced by the fact that he had ordered his fellow conspirators in Berlin to stand by to initiate Valkyrie. He had also ordered the aide who accompanied him to the Berghof, Captain Friedrich Klausing (Haeften was ill), to have a Heinkel HE.III aircraft on standby at Salzburg ready to fly him back to Berlin to take command of the putsch. However, when news of the latest failure reached the capital, Carl Goerdeler, ‘half laughing, and half crying’ shook his head and predicted: ‘They’ll never do it.’ Following the failure, Stauffenberg, Klausing and the other conspirators present at the Berghof – Stieff, communications chief General Fellgiebel and Lieutenant-Colonel Bernhard Klamroth – met at the Frankenstrub barracks outside nearby Berchtesgaden for an anguished post-mortem before Stauffenberg and Klausing flew back to Berlin. They resolved to make another attempt as soon as possible.

That same night, Stauffenberg’s cousin Colonel Casar von Hofacker, a man whose resolution and moral determination matched that of Stauffenberg himself, arrived in Berlin from Paris to report on the catastrophic military situation unfolding in France. Paris, Berlin and Tresckow’s Army Group Centre headquarters in the Ukraine, were the three places where the plotters’ concentration was strongest.

The military governor of France, General Karl-Heinrich von Stülpnagel, was the leader of the plot there, and Hofacker himself was its liaison man with Berlin. They were ably abetted by several other strong personalities, including the Swabians General Hans Speidel, Chief of Staff to Field Marshal Erwin Rommel – whose Army Group B was currently struggling to contain the Allied bridgehead in Normandy – and Colonel Eberhard Finckh, Stülpnagel’s newly appointed Chief of Staff.

The new Commander-in-Chief in the west was Field Marshal Günther von Kluge, who, recovered from the serious injuries he had sustained when his car had overturned in Russia the previous October, had been appointed to succeed the ageing Gerd von Rundstedt, with a brief to save the situation in France. Kluge was as indecisive as he had been when Tresckow had attempted to recruit him to the conspiracy in Russia. Although, as one of Germany’s brightest military brains, Kluge knew that the war was lost, he lacked the essential moral courage necessary to do what Stülpnagel and Hofacker were urging: to throw in the towel and negotiate a separate peace with the Allies.

Günther ‘Hans’ von Kluge.

Rommel, too, always a simple soldier who steered clear of politics as far as he could, resisted Speidel’s wheedling attempts to enlist his heroic name to the conspirators’ ranks. After failing to throw the Allies back into the sea on what he called ‘the longest day’ following the invasion (he had been absent on leave in Germany celebrating his wife’s birthday), he also knew that the war was irretrievably lost. He was happy to say as much to Hitler, but he baulked at actually overthrowing, still less assassinating, the Führer. Hofacker had gone to Berlin to meet Beck and Stauffenberg with his pessimistic report of what was really happening on the Normandy front fresh from a face-to-face meeting with Rommel on 9 July.

On the night of 12 July, the Abwehr’s Hans Bernd Gisevius – who had been in contact with Allen Dulles, the local chief of America’s secret service, the OSS, on behalf of the plotters – returned to Berlin from Switzerland, bringing with him more bad news: there was no way, he told his fellow conspirators, that the Western Allies would make a separate peace with Germany against their Soviet ally. Despairingly, Stauffenberg asked Gisevius whether there was any chance of making an ‘eastern peace’ with the Soviets alone. Gisevius brutally replied that the same applied; there was no hope that either the Soviets or the Western Allies would agree to anything less than Germany’s unconditional surrender.

The two men disagreed violently. Gisevius resented Stauffenberg’s sudden emergence as the guiding light of the conspiracy in place of his old chief, Oster, forgetting that Oster was now under virtual house arrest. Stauffenberg, for his part, disliked Gisevius’s openly expressed ambition to be placed in charge of purging Nazis after the putsch. They parted on bad terms, but Gisevius, for all his post-war sneering at Stauffenberg as a ‘military praetorian’ who had an inferiority complex about his own injuries, was forced to admire the maimed colonel’s courage and his single-minded determination to carry out the assassination, come what may. ‘This evening,’ he concluded, ‘I really had the impression that someone here was going all out.’

On 14 July Hitler abruptly moved his headquarters from the Berghof to Rastenburg, despite the fact that the advancing Russians were now less than 100 kilometres from his eastern headquarters in the sweltering Polish forests. Fromm and Stauffenberg were summoned to an urgent lunchtime conference with Hitler the next day to discuss the provision of Reserve Army reinforcements for the hard-pressed Eastern Front. This news triggered a flurry of frenzied activity among the conspirators. At a meeting that afternoon attended by the leading figures, Beck, Goerdeler, Olbricht and Stauffenberg, it was agreed that Stauffenberg would attempt the assassination the next day regardless – even without the presence of Goering and Himmler. For their part, the conspirators in Berlin agreed to activate Valkyrie, with Olbricht issuing orders to move troops into the centre of the capital at 11 a.m., two hours before Stauffenberg was due to explode his bomb.

Meanwhile, back in France, at his headquarters in the riverside château of La Roche-Guyon, Rommel – urged on by his fellow Swabian and Chief of Staff Speidel – drafted an ‘ultimatum’ to Hitler insisting that the position in the west was now hopeless and that peace terms must be sought. His message concluded: ‘The troops are fighting heroically everywhere, but the unequal struggle is nearing its end. I must beg you to draw the political conclusions without delay. I feel it is my duty as commander-in-chief of the Army Group to state this clearly.’

Stauffenberg (left) meeting Hitler at the Wolfschanze on 15 July 1944. Stauffenberg had a bomb with him but did not detonate it. He appears not to be carrying his briefcase – had a nervous Stieff already hidden it?

On 15 July Fromm and Stauffenberg, again accompanied by Captain Klausing, flew out on an early morning flight from Berlin, breakfasted at the Wolf’s Lair, and met with Keitel for a preparatory briefing. Stauffenberg also communicated with the conspirators’ main men at Hitler’s headquarters, Stieff and Fellgiebel. They then met Hitler. At around this time a photographer took the only photograph of Hitler with his would-be assassin. Stauffenberg stands to the left of the picture, rigidly at attention, betraying no hint of the tension he must have been under, his injuries hidden from the camera. Hitler, a small and shrunken figure with his cap pulled low over his eyes, shakes hands with General Karl von Bodenschatz, Goering’s Luftwaffe liaison man at Hitler’s headquarters. At about 1 p.m. the party proceeded to the briefing hut, a one-storey wooden structure, reinforced by brick supports and a concrete ceiling, with large steel-shuttered windows. This was the eventual location for the explosion of Stauffenberg’s bomb on 20 July. That bomb should have exploded now, on 15 July: why didn’t it?

Explanations for this latest failure differ. According to one report, Stieff and Fellgiebel were insistent that no attempt must be made without Himmler being present. Stieff, according to this story, was so worried that Stauffenberg was going to go ahead anyway that he sabotaged the assassination by physically removing the briefcase bomb while Stauffenberg was telephoning Berlin to acquaint the plotters in the capital with the unfolding situation. According to another version, Stauffenberg was unexpectedly called to present his report early in the conference before he had a chance to prime the bomb. A third version states that Hitler ended the conference unexpectedly early, while Stauffenberg was phoning Berlin.

At all events, as Stauffenberg ruefully remarked to Klausing as they disconsolately trooped off to lunch on board Keitel’s special train, ‘It all came to nothing again today.’ Stauffenberg had managed to call Olbricht in Berlin to tell him that yet another attempt had failed. It was too late to call off Valkyrie’s preliminary moves – the codeword had been issued at 11 a.m. as arranged, and troops from the city’s guard battalions and army cadet schools had obediently begun to move into the city centre. Olbricht hastily countermanded the order personally: driving to Potsdam and Gleinicke, and returning the troops to their barracks, but the manoeuvres could not be concealed from his superiors, who were both irritated and puzzled by these unauthorised troop movements. Olbricht lamely explained that the codeword had been issued merely to test the troops’ efficiency and readiness, but a furious Fromm tore a strip off him for issuing the unauthorised command. The same trick could not be repeated – next time, the bomb would have to explode.

16 July was spent by the conspirators in another lengthy autopsy on why their latest attempt had failed. Stauffenberg met first with Beck and Olbricht. All their nerves were wound up to breaking point. Beck’s housekeeper testified later that the old general, who had recently been operated on for stomach cancer, woke each morning with his sheets soaked through with sweat. Stauffenberg, too, was understandably but uncharacteristically tired, irritable and nervous. Three times now he had keyed himself up to do what he described as ‘the dirty deed’ and three times had seen his action aborted. Even his deep reserves of courage must have had a limit. Olbricht stated that the issuing of the Valkyrie codeword and its subsequent cancellation had reached the ears of a suspicious Keitel. They must act for real – and soon. Snatching at straws, they argued about whether a collapse of the Western Front and a separate peace with the Anglo-Americans was, after all, possible.

The discussion of the plotters’ ever-narrowing options continued that night at Stauffenberg’s home in the Tristranstrasse. The core younger conspirators from Stauffenberg’s closest circle were present, including his brother Berthold; Mertz von Quirnheim, who, under Olbricht would initiate Valkyrie in Berlin; Casar von Hofacker, Stauffenberg’s cousin and the plotters’ man in Paris; another cousin Peter Yorck von Wartenburg; Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenburg and Adam von Trott zu Solz. Talking late into the night they chewed over the hard facts, always arriving at the same conclusion: nothing could be done until Hitler was eliminated, and even then the chances of success were vanishingly slight. Nonetheless, they concluded, the act must be attempted to redeem Germany’s honour. Compared to this, as Tresckow had told Stauffenberg, nothing else counted.

Underlining the hopelessness of the Reich’s military position, on 17 July offensives opened both on the Eastern Front and in Normandy, where the Allies appeared on the point of breaking out of their bridgehead and capturing the cities of Caen and St Lô. The same day, the Normandy commander, Rommel, was seriously hurt when his staff car was strafed by an American fighter. The ‘Desert Fox’ suffered head injuries requiring his hospitalisation in Germany.

On 18 July more bad news crowded in, confirming the tightening circle within which the plotters were now operating. One of the more unlikely conspirators, the president of Berlin’s police, Count von Helldorf, who had an equivocal record as an ardent – if corrupt – former Nazi, tipped Stauffenberg off that a warrant had been issued for the immediate arrest of Carl Goerdeler, nominated by the plotters for the post of Chancellor in the post-putsch government. Stauffenberg immediately passed on the warning to Goerdeler, who went into hiding. Hard on the heels of this disturbing news came even more worrying tidings. A naval officer, Lieutenant Commander Alfred Kranzfelder, told Stauffenberg of a rumour he had heard from a Hungarian nobleman that Hitler’s headquarters were to be blown sky-high over the next few days. The young Hungarian had heard the report from the daughter of General Bredow, murdered by the Nazis in the Night of the Long Knives purge. She in turn had apparently picked it up from Stauffenberg’s own indiscreet aide-de-camp, Werner von Haeften. Not only were the Gestapo now breathing down the conspirators’ necks, but their own plans were about to become Berlin street gossip. Stauffenberg knew that he must act, and fast; he told Kranzfelder: ‘We have crossed the Rubicon.’ As if to confirm his resolve, and his fate, another summons arrived from Rastenburg: Stauffenberg was called to attend a conference there on 20 July.

Stauffenberg’s aide-de-camp Lieutenant Werner von Haeften who was at his side on 20 July.

The conspirators had less than twenty-four hours to prepare their putsch. 19 July was spent in frantic checking of their necessarily ad hoc arrangements. Thanks to Olbricht’s patient spadework, the basic rudiments were in place but much – too much – still depended on chance: whether individual commanders would remain loyal to the regime or rally to the putsch. Above all, everything depended on whether Stauffenberg would succeed in killing Hitler. One key plotter was Major-General Paul von Hase, the military commander of Berlin. A vital element in Hase’s command was the Grossdeutschland Guard Battalion, commanded by a Major Otto Remer, a much-decorated veteran of the Eastern Front. Hase failed to establish where Remer’s loyalty would lie on the day of the planned putsch, though he could well have guessed. When it was pointed out to him that Remer, among his many other medals, proudly sported a Hitler Youth gold badge on his army uniform, indicating that he was a convinced – not to say fanatical – National Socialist, Hase swept the observation aside, blithely assuming that Remer would obey his orders. He even turned down the suggestion that Remer should be sent on an assignment to Italy to make sure that he was out of the way on the day. It was to prove a fatal mistake.

To support the troops in Berlin, another conspirator, Major Philipp von Boeslager, commanding the 3rd Battalion of the 31st Cavalry Regiment, had been asked by his brother Georg von Boeslager, commander of the 3rd Cavalry Brigade, to move six squadrons of his horsemen, about 1,200 men, to airfields in Poland, ready to fly into Berlin to back up the putsch. Astonishingly, Major Boeslager, in a five-day ride, covering some 600 miles, actually accomplished this manoeuvre, arriving at Brest-Litoskv on 19 July, ready to board lorries for the airfield the following day.

Stauffenberg, the man at the centre of this gathering storm, spent the day in meetings with his fellow plotters. In the early evening he called on one of them, General Eduard Wagner, quartermaster general of the Wehrmacht, at his office at the Zossen military base outside Berlin to ask that Wagner’s personal Heinkel HE.III plane should be made available next morning to fly him to Rastenburg, and then to return him to the capital after the assassination. Wagner readily agreed to the request. Afterwards, and presumably by way of relaxation, Stauffenberg and Wagner acted as ‘beaters’ during a hare hunt in the fields around Zossen, driving the frightened animals towards a colleague of Wagner’s who killed them with a shotgun. Did Stauffenberg reflect that on the following day he would be hunting rather bigger game?

Captain Freiherr Georg von Boeslager.

While this was going on, Stauffenberg sent his personal driver, Karl Schweizer, to obtain the explosive with which he would make the attempt, which had been ‘minded’ for him in-between his recent trips to see Hitler by a fellow conspirator, Fritz von der Lancken. Schweizer was in blissful ignorance of the contents of the two packages tied with string and neatly packed in a briefcase that he drove back to his master. Returning to Tristranstrasse, Stauffenberg had Schweizer stop outside a Catholic church into which he disappeared. One can only speculate what anguished prayers he offered up: success for his mission? Forgiveness for the lives his bomb would inevitably take? Divine protection for his friends and family?

On arriving home, Stauffenberg showed his brother Berthold the explosives, which he wrapped in a shirt before stowing them away again. Some time that same evening, he attempted to call Nina in Lautlingen, but an Allied bombing raid had severed the phone lines between Berlin and Lautlingen, and he was unable to get through.

Thursday 20 July 1944 dawned hot and sultry. A sweltering day of high summer heat was in prospect. At No. 8 Tristranstrasse, the Stauffenberg brothers rose early. Schweizer arrived with the staff car at 6 a.m., and Stauffenberg, taking Berthold with him for company, drove off through the suburbs of the city showing the ugly scars of recent Allied bomb damage. At Rangsdorf airport they rendezvoused with Stauffenberg’s aide-de-camp and co-conspirator Werner von Haeften, the handsome thirty-five-year-old former Berlin banker seconded, like Stauffenberg, to the Reserve Army after suffering severe war wounds. Werner was accompanied by his brother, Berndt, who had come to see him off and whose Christian scruples had originally prevented Werner von Haeften from volunteering for the assassination himself. Such principles had evidently been overcome, for Haeften, like Stauffenberg, carried in his briefcase as backup about two pounds of plastic hexite explosive, into which British-made primers with thirty-minute fuses had already been sunk. Also at the airport, boarding the same flight to Rastenburg, was the irresolute General Stieff and his aide, Major Roll.

Slightly delayed by early morning mist, the Heinkel took off after 7 a.m. and flew east-north-east across the Prussian plain towards the forests of northern Poland where the Wolf’s Lair lay, some 350 miles away. They landed soon after 10 a.m. and separated; Stieff and Roll driving to their posts, accompanied by Haeften carrying both explosive briefcases, while Stauffenberg was driven the ten miles through two SS checkpoints to the Wolf’s Lair, the forbidding forest clearing described by General Alfred Jodl as ‘a cross between a monastery and a concentration camp’. As on his last visit on 15 July, Stauffenberg breakfasted with colleagues in the officers’ mess known as ‘the casino’. He also gave a preliminary run-through of the subjects he would cover in the conference to General Walther Buhle, chief of the army’s General Staff.

At 11.30 a.m. Stauffenberg rejoined Haeften and passed from the Wolf’s Lair’s outer zone, Sperrkreis 2, into the highly guarded inner zone, Sperrkreis 1, where Hitler lived. Here they went to Field Marshal Keitel’s office hut for another preliminary briefing. Haeften, as befitted his junior status, was not admitted to this meeting, but waited outside in a corridor with his telltale heavy briefcase, which he attempted to conceal beneath a tarpaulin. His jumpy manner attracted the attention of a Keitel aide, Staff Sergeant Werner Vogel, who asked who the conspicuously bulky briefcase belonged to. Haeften replied that Stauffenberg needed it for the conference, and promptly removed it from the inquisitive sergeant’s presence.

Stauffenberg and Haeften had expected the conference to start at midday, but Stauffenberg learned from Keitel just before 12.00 p.m. that it had been put off until 12.30 p.m. while preparations were made to receive Mussolini; the deposed Duce was visiting Rastenburg that same day. Stauffenberg took advantage of the delay to ask Keitel’s adjutant, Major John von Freyend, if there was a convenient room nearby where he could change his sweat-soaked shirt, and freshen up for the conference after his long flight. It seemed a reasonable request; the heat of the day was approaching its height, and under the glowering trees and camouflage canopies of the gloomy Wolf’s Lair – a place hated by all its forced inhabitants, apart, apparently, from Hitler himself – the atmosphere was oppressively stuffy and muggy.

Stauffenberg’s real purpose, of course, was to win a few minutes on his own with Haeften so that they could prime the bomb in the briefcase that he would carry into the conference. He had with him in the pocket of his uniform tunic a small pair of specially adapted pliers that he would use to squeeze the copper casing around the glass phial containing the acid that would eat through the detonator wire which would then ignite the charge. No detail of this operation had been left to chance. Stauffenberg’s brother Berthold had encased the pliers in rubber and bent the handles, the better for his brother’s remaining three fingers to grip, and Stauffenberg had practised squeezing the phial time and time again, until he could execute the delicate operation practically blindfold in a few seconds.

John von Freyend obligingly showed Stauffenberg and Haeften – ostensibly needed to help the maimed man on with his shirt – to his own quarters. Staff Sergeant Vogel, the nosy NCO who had earlier seen Haeften’s suspicious-looking parcel, passed by again and saw the two men bent over some object. At that moment, around 12.25 p.m., General Fellgiebel, the communications chief whose job it would be to shut down the Wolf’s Lair’s links with the outside world after the explosion, telephoned on an internal line and asked to speak to Stauffenberg. Freyend told Vogel to get him and remind him that the conference was starting and that Hitler hated being kept waiting. Obediently, the inquisitive sergeant returned to his boss’s sitting room and opened the door.

Stauffenberg, however, was standing with his back against the door, blocking Vogel’s entry. The staff sergeant gave his message, and an agitated-sounding Stauffenberg answered that he would be along directly. Vogel’s summons was reinforced by Major John von Freyend, who barked from the hut’s door, ‘Do come along, Stauffenberg!’ The two assassins knew they could delay no more, even though their task was only half complete. They had succeeded in priming Stauffenberg’s bomb, but had intended to add to the load the explosive that Haeften was carrying. There was now no time for this.

The interruption almost certainly saved Hitler’s life, for had the second two-pound explosive slab been added, explosives experts agree, everyone round the conference table would certainly have been killed.

Hastily stowing the single explosive slab, Stauffenberg snapped the tanned leather briefcase shut. Inside, the acid was already eating through the wire that, given the hot conditions, might explode within a quarter of an hour rather than the thirty minutes it normally took. Stauffenberg left John von Freyend’s room and joined him and Keitel, who were impatiently waiting outside the hut.

A Time Pencil detonator, similar to the device which Stauffenberg would have used.

Seeing the maimed man weighed down by the heavy briefcase, John von Freyend offered to carry it, put out his hand and gripped the handle. But Stauffenberg, John later testified, practically tore the case out of his grasp, with an energy that even the suspicious Vogel, watching the incident, had to admire. Then Stauffenberg, perhaps worried that his behaviour would arouse suspicion, relented and allowed Major John to carry it, explaining that he wanted to be placed as near to Hitler as possible, as his hearing was not good since his African injuries. Stauffenberg then joined Generals Keitel and Buhle for the rest of the three-minute walk across to the conference hut, while Haeften hurried off to ensure that the staff car would be available for their anticipated hasty departure. During the short stroll to the conference Stauffenberg engaged Buhle in animated talk.

When they arrived, it was about 12.35 p.m. and the conference had already begun. The four men took their places around the large rectangular oak map table that occupied most of the ten by four metres (thirty three by thirteen feet) space in the briefing room, with a few smaller tables for phones and radios around the walls. The windows were flung open in the stifling heat. There were now twenty-five men gathered around the table. Stauffenberg squeezed in next and to the left of Colonel Heinz Brandt, the General Staff officer who had himself escaped death when he had acted as the unwitting courier carrying Tresckow’s and Schlabrendorff’s bottle bomb on board Hitler’s aircraft the previous year. He would not be so lucky today.

Directly to Stauffenberg’s left was Luftwaffe General Günther Korten; then came General Adolf Heusinger, operations chief of the OKH, who was reporting on the critical state of the Eastern Front as they came in.

Hitler was seated on Heusinger’s left, three places down the table from Stauffenberg, who slid his deadly briefcase under the table, as close to the Führer as he could. Hitler acknowledged their late arrival with a searching stare, then motioned Heusinger to continue with his report. Another observer who saw Stauffenberg’s arrival from his position three places further down the table from Hitler was General Walther Warlimont, Heusinger’s deputy chief of operations. Stauffenberg had, recalled Warlimont,

the classic image of the warrior through all history. I barely knew him, but as he stood there, one eye covered by a black patch, a maimed arm in an empty uniform sleeve, standing tall and upright, looking directly at Hitler who had now also turned round, he was . . . a proud figure, the very image of the general staff officer . . . of that time.

Keitel announced that Stauffenberg would be reporting on the Reserve Army’s state of organisation and Hitler shook his would-be assassin’s remaining hand. Heusinger’s gloomy report on the dire state of the Eastern Front continued. He was just saying that the position around Lemberg was desperate, and would collapse unless reinforced with reserves when Keitel broke in, fussily suggesting that this was a good opportunity for Stauffenberg to report on the readiness of the Reserve Army to supply reinforcements. Hitler demurred, saying that Heusinger should complete his report on the rest of the Eastern Front, and that he would hear Stauffenberg later.

This was Stauffenberg’s chance, the window of opportunity he needed to slip away without attracting suspicion. He left his place at the table and whispered to Keitel, who had taken his usual place at Hitler’s left hand, that he needed to take an urgent phone call from Berlin on the latest information regarding reserves available for Russia. Keitel, delayed by Stauffenberg for the second time that day, frowned in annoyance but could hardly refuse. He nodded brusquely and Stauffenberg slipped out of the room, beckoning to John von Freyend whose assistance he needed again, this time to get General Fellgiebel on an internal phone. John ordered a telephone operator, Sergeant Adam, to connect Stauffenberg and returned to the conference.

Back in the briefing, Heusinger had resumed his report. As he did so, Colonel Brandt leaned in over the table to get a closer look at the maps and accidentally kicked Stauffenberg’s heavy briefcase over. He leaned down to stand it upright, and in doing so pushed it further under the table so that one of the table’s two stout wooden supports now stood between the briefcase and Hitler. Heusinger’s report was drawing to a close. To his intense annoyance Keitel saw that Stauffenberg had not returned. He left the conference to find the errant colonel, and to his surprise heard from Sergeant Adam that Stauffenberg had disappeared without making a call. Thoroughly mystified, Keitel returned to the briefing.

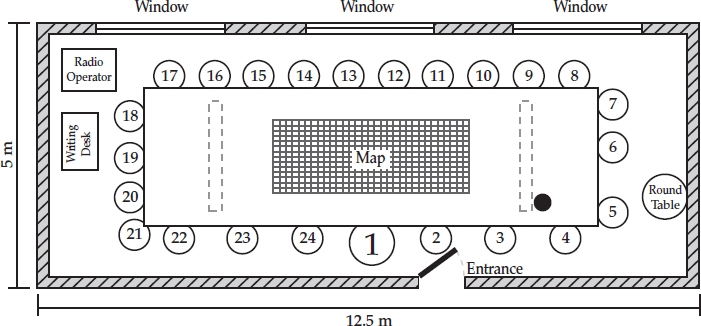

The Map Room at the Führer’s Headquarters, Rastenburg at 12.42 p.m. on 20 July 1944

1. Adolf Hitler

2. General Heusinger

3. Luftwaffe General Korten

4. Colonel Brandt

5. Luftwaffe General Bodenschatz

6. General Schmundt

7. Lieutenant-Colonel Borgmann

8. Rear Admiral Puttkamer

9. Stenographer Berger

10. Naval Caption Assmann

11. General Scherff

12. General Buhle

13. Rear Admiral Voss

14. SS Group Leader Fegelein

15. Colonel Below

16. SS Hauptsturmführer Gunsche

17. Stenographer Hagen

18. Lieutenant-Colonel John

19. Major Büchs

20. Lieutenant-Colonel Weizenegger

21. Ministerial Counselor Sonnleithner

22. General Warlimont

23. General Jodl

24. Field Marshal Keitel

● Bomb in briefcase under the table

Once John had gone, Stauffenberg put the phone down and, in his haste forgetting his cap and belt, crossed to Fellgiebel’s communications centre a few hundred yards away, where he had arranged to meet Haeften and Fellgiebel himself. They stepped out of the building to where their car was waiting, so that they could have a good view of the conference hut. Haeften got into the car. Stauffenberg, understandably, nervous, lit a cigarette and distractedly talked to Fellgiebel.

At 12.42 p.m. the briefcase bomb exploded. A deafening blast roared out and a choking cloud of smoke and dust rose from the hut. So violent was the blast that many of those present thought that a passing Russian plane had dropped a bomb, and Stauffenberg himself compared it to a direct hit from a 150-mm shell. One of those inside the conference, General Warlimont, described the impact:

In a flash the map room became a scene of stampede and destruction. At one moment . . . a set of men . . . a focal point of world events; at the next there was nothing but wounded men groaning, the acrid smell of burning; and charred fragments of maps and papers fluttering in the wind. I staggered up and jumped through the open window.

The pandemonium was intense. One man was blown through an open window, but got up unhurt and ran to summon help; others, Hitler included, had their clothes torn to shreds or burned into their bodies. The heavy oak conference table had been shattered into three sections, and segments of the concrete roof had come crashing down. Through the chaos, the stentorian voice of Field Marshal Keitel could be heard demanding: ‘Where is the Führer?’ Stauffenberg did not hang around to see the full results of his handiwork. Assuming from the force of the blast that Hitler was indeed dead, Stauffenberg chucked his cigarette, leapt into the car alongside Haeften and ordered the driver to head hell for leather to the airfield. Hitler, however, was very much alive.

Fellgiebel, abruptly abandoned by Stauffenberg to his crucial task of closing down Rastenburg’s communications, saw with mounting horror the Führer come staggering out of the smoking debris of the conference hut, supported by the ever-loyal Keitel, who was sobbing ‘My Führer; you’re alive; you’re alive!’ The dictator presented an appalling spectacle: his hair had been set alight; his right arm and leg burned and partially paralysed through shock; his black trousers were trailing around his blooded, splinter-flecked legs in tattered ribbons; and both his ear-drums had burst. His buttocks, as he ruefully jested later, had been bruised ‘as blue as a baboon’s behind’ by the impact of him being flung headlong on the floor by the blast. As Hitler staggered away from the carnage, behind him four of his lieutenants lay dead or dying, two others had life-threatening injuries and almost everyone else in the room had suffered burns and/or shock and concussion.

The Wolfschanze conference room after the explosion.

Warlimont, slightly concussed, helped the luckless Colonel Brandt, whose leg had been shattered when the briefcase exploded almost under his feet, and who, shocked, was trying to heave himself across a window ledge. Having accomplished his act of mercy for his comrade, Warlimont’s head started to swim, his ears buzzed, and he fainted. Along with Brandt, those who subsequently succumbed to the injuries caused by Stauffenberg’s bomb were General Korten, General Rudolf Schmundt and a stenographer named Berger who was killed outright.

At about 12.50 p.m. Stauffenberg’s car was halted at Guardpost 1, the checkpoint separating the inner Sperrkreis 1 from the outer Sperrkreis 2 zone. Although a formal alarm had not been raised, the lieutenant in charge of the checkpoint had heard the bang and seen the smoke and accordingly dropped the barrier. But he recognised Stauffenberg, who told him that he had to get to the airport urgently. As the alarm had not yet been raised, the lieutenant let him pass. Stauffenberg drove on to reach the southern guard post of Sperrkreis 2. By this time, the alarm had sounded and the barriers had been firmly closed by the checkpoint’s commander, a Sergeant Kolbe. It looked as though Stauffenberg and Haeften were trapped in the Wolf’s Lair. But Stauffenberg’s iron nerves and quick mind did not fail him at this critical juncture. Calmly, he told Kolbe the story that had got him through the first checkpoint: that he needed to drive to the airport as a matter of the utmost urgency. Kolbe was adamant: once the barriers were down, no one could leave. Stauffenberg insisted that Kolbe telephone the Wolf’s Lair headquarters, where he spoke to an adjutant, a cavalry captain named Leonhard von Mollendorf who had been one of the officers with whom Stauffenberg had breakfasted that morning. Stauffenberg took the phone from Kolbe and tersely told Mollendorf that he had the permission of Rastenburg’s commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Gustav von Streve, to leave the complex, as he had to fly by 1.15 p.m. at the latest. As Streve had been called to the scene of the explosion, Stauffenberg’s story could not be verified, but Mollendorf was aware that he was an officer with permission to be at Rastenburg, and was anyway severely crippled, so he ordered Kolbe to let him through. The car tore on to the airport. En route, the driver saw Haeften take a small brown paper parcel and toss it from the car: it was the unused slab of plastic explosive and was later recovered by the Gestapo. At 1.15 p.m., heaving huge sighs of relief, Stauffenberg and Haeften took off for Berlin.

An SS soldier holding the shredded trousers Hitler wore during the assassination attempt. Hitler sent the trousers to Eva Braun for safekeeping with a note explaining they would be proof of his historic destiny.

A photograph of the conference room, taken on 20 July 1944.

Back in the Bendlerstrasse, the conspirators had spent the morning marking time. No news could be expected until about 1 p.m. Olbricht had been joined in his office at 12.30 by General Erich Hoepner, the former Panzer commander who had been dismissed in disgrace by Hitler in January 1942 for the crime of withdrawing his tanks from before Moscow. Forbidden even to wear Wehrmacht uniform, the humiliated Hoepner, who had not been involved in plotting since the abortive Oster putsch of 1938, had renewed his links with the conspirators in his enforced retirement. Now, carrying his forbidden uniform in a suitcase, he joined Olbricht for lunch while they awaited news from Rastenburg. Over a bottle of wine they toasted the success of the putsch.

The unused bomb: the parcel of explosive with primer charge thrown from their car by Stauffenberg and Haeften as they fled – would it have made the difference?

The remnants of Stauffenberg’s briefcase pieced together by Gestapo investigators after the bomb it contained exploded.

But the first news from Rastenburg was ambiguous in the extreme. Fellgiebel had been speared on the horns of a dilemma as he saw Hitler staggering from the scene of the bomb: if he blocked communications as scheduled, he would immediately attract attention and suspicion. The truth was that the conspirators had made no provision for this eventuality. They were used to aborting putsches at the last minute after the many occasions when an assassination attempt had been planned but had not taken place. What they had not reckoned on was the current circumstance; a bomb had gone off – but Hitler had survived the blast. Fortunately for Fellgiebel, he was temporarily relieved of the terrible burden of his responsibility by the Nazis themselves: Hitler ordered his own communications blackout – although the Nazi leadership and the Wehrmacht’s higher command, including Fellgiebel himself, could use the phone, all other phone, radio and teletype communications out of Rastenburg were blocked. Hitler was adamant: until it was discovered who was behind the bomb, no news of it should reach the outside world. Gratefully, Fellgiebel confirmed the blackout. Then, as he walked up and down the path that led by the Führer’s personal quarters, unsure of what to do next, he saw Hitler himself emerge and walk shakily around his own compound. He was clearly not even seriously hurt.

Dismayed, Fellgiebel put through a call to the Bendlerstrasse on his personal phone. It was 1.30 p.m. The call was taken by General Friedrich ‘Fritz’ Thiele, one of the conspirators. Fellgiebel was brief, and opaque. In a totalitarian state, hostile ears would probably be listening. ‘Something terrible had happened,’ he reported, then perceptibly paused before adding, ‘the Führer is alive’. The news threw Thiele and Olbricht into dithering doubt. Too late, they now realised that no provision had been made for this eventuality. If Stauffenberg’s bomb had misfired they could have done nothing – and got away with it. But now that the blast had occurred, there was no chance of covering it up. They conferred with the army’s quartermaster general, Eduard Wagner, at Zossen, on board whose plane Stauffenberg was now winging back to Berlin, blissfully believing that his bomb had killed Hitler. Between them, the three generals decided to sit tight and wait for more news from Rastenburg.

The long, hot afternoon wore on. Only one officer in the Bendlerstrasse seemed possessed of the same resolute spirit as his friend Stauffenberg – Colonel Mertz von Quirnheim. At about 1.50 p.m., having heard that Stauffenberg’s bomb had exploded, Mertz tried to activate Valkyrie. He told another conspirator, General Staff Major Hans-Ulrich von Oertzen, a protégé of Tresckow, to issue the necessary orders to the Armoured School at Krampnitz outside Berlin to send its vehicles into the centre of the capital and prevent the SS from launching a counter-coup out of their barracks at Lichterfelde. Two advance vehicles actually arrived outside the school but, seeing no unusual activity, were redirected to the Siegessaule (Victory Column) near the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin’s very heart. Mertz also ordered units from the Infantry School at Doberitz to move into the city centre. At 2 p.m. Mertz next summoned all available officers from the General Staff of the Reserve Army and told them that Hitler had been assassinated, and that the army was taking control of the country to ensure internal order. The Waffen SS would be incorporated into the Wehrmacht, said Mertz, and Field Marshal Witzleben would be the new army commander. Retired General Ludwig Beck would be the new head of state.

Orders for carrying out Valkyrie also reached the conspirators in Paris. Soon after 2 p.m. Colonel Eberhard Finckh, chief of staff to the Western Command, received a mysterious anonymous phone call at his offices in the rue de Saurene from a source at the Zossen military base outside Berlin. The voice gave the agreed word for launching the coup ‘Abgelaufen’ (launched), repeated it, then rang off. Immediately, Finckh called for his car and drove to the St Germain headquarters of General Günther von Blumentritt, chief of staff to Field Marshal Kluge, who was away on an inspection trip to the crumbling Normandy front. Blumentritt was a jovial, rotund soldier who – although no Nazi – was not a party to the plot.

Kluge’s deputy in France, General Günther von Blumentritt (left) approved of the plot but was not one of the conspirators. General von Boineburg (centre, with monocle) arrested all 1,200 SS men in Paris on 20 July in a flawless operation.

Arriving around 3 p.m. Finckh greeted Blumentritt and got straight to the point. ‘Herr General, there has been a Gestapo putsch in Berlin,’ he began. ‘The Führer is dead. A provisional government has been formed by Witzleben, Beck and Goerdeler.’ There was a minute’s silence while Blumentritt digested the information.

‘I’m glad it’s they who have taken over,’ he responded, ‘they’re sure to try for peace. Who gave you this news?’ Finckh lied glibly: ‘The military governor,’ he replied, knowing that Stülpnagel was a fellow plotter.

Without further ado, Blumentritt picked up his phone and was put through to Kluge’s forward headquarters at the château of La Roche-Guyon – the building that had been Rommel’s headquarters until he had sustained his injuries three days before. General Hans Speidel, another conspirator, answered the phone and said that Kluge was still incommunicado visiting frontline units. Blumentritt was guarded: ‘Things are happening in Berlin,’ he said enigmatically, then whispered the single word ‘Tot’ (dead). At once Speidel was full of questions: who was dead, and how? Blumentritt, knowing that phones were vulnerable to eavesdroppers, refused to elaborate and hung up. After a few moments’ chat, Finckh took his leave and returned to Paris. By the time he arrived, it was 4.30 p.m.

Stauffenberg and Haeften landed back at Berlin’s Rangsdorf airfield just before 3.45 p.m. There was an immediate mix-up: Schweizer was not at the airport to meet them, and there was a delay while another car and driver were summoned. Haeften used the time to call the Bendlerstrasse just before 4 p.m. He told his fellow conspirators that the assassination had succeeded and that Hitler was dead. They then set out on the thirty-kilometre drive to the Bendlerblock, arriving around 4.30 p.m.

In the meantime, although Olbricht had sat on his hands, Mertz had not been idle. At 4 p.m. he ordered the issuing of the second stage of the Valkyrie orders, with the proclamation that began with the words ‘The Führer, Adolf Hitler, is dead!’ and ended with the announcement of martial law. Mertz, dragging a reluctant Olbricht – who already knew that with Hitler alive the putsch was a lost cause – had crossed the final Rubicon. Olbricht plucked up the courage to get his superior officer on board. He hastened to the office of General Fromm and told him without further ado that Hitler had been assassinated and that he proposed issuing the orders for Operation Valkyrie to begin. Fromm would not be rushed. He insisted on calling Rastenburg to get confirmation of the Führer’s death. Olbricht himself picked up the phone on Fromm’s desk and Fromm was put through to Keitel.

‘What’s happening at Rastenburg?’ asked Fromm, ‘There are the wildest rumours circulating here.’

‘Nothing at all,’ replied the Field Marshal. ‘Everything’s normal here. What have you heard?’

‘I’ve just had a report that the Führer’s been assassinated.’ said Fromm.

‘Rubbish,’ asserted Keitel, before admitting that an attempt had indeed been made on Hitler’s life. ‘Fortunately, it failed,’ he added. ‘The Führer is alive and only slightly injured.’ Then Hitler’s ‘nodding donkey’ switched subjects: ‘Where, by the way, is your Chief of Staff, Colonel Count Stauffenberg?’ Fromm replied that Stauffenberg had not yet returned from Rastenburg and rang off. He told Olbricht that in view of the Führer’s survival, it was not necessary to activate Valkyrie. Olbricht, who knew that the plan had already been launched, returned to his office to anxiously await Stauffenberg’s arrival.

Heinrich Himmler, feared overlord of the SS.

Ernest Kaltenbruner, Heydrich’s successor and in charge of investigating the July plot. Here seen on trial at Nuremberg with Field Marshal Keitel sitting on his right. Both were hanged.

At Rastenburg, SS overlord Heinrich Himmler had sped from his own headquarters half an hour away to take personal charge of the investigation into the bombing. Suspicion first fell upon foreign construction workers employed at the complex, but when the telephone operator Sergeant Adam spoke up about the peculiar behaviour of Stauffenberg at the time of the blast – including his forgetting his cap and belt in his confusion – others recalled his hurried departure and began to put two and two together. Hitler’s ubiquitous private secretary, Martin Bormann, brought Adam to his master for a personal interview. The Führer quizzed the operator closely before quickly coming to the conclusion that Stauffenberg had been responsible for planting the bomb. As yet, however, there was no suspicion of a wider conspiracy.

Himmler lost little time in ordering his No. 2, Ernst Kaltenbrunner – the towering, scar-faced Austrian who had taken over control of the RSHA (Reich Security Main Office) after Heydrich’s assassination – to take charge of the investigation into the bombing. Kaltenbrunner was in Berlin and, ironically, flew to Rastenburg from Rangsdorf airfield – the very same destination that Stauffenberg was flying to: their aircraft crossed in flight. Himmler himself took off for Berlin in hot pursuit of Stauffenberg and Haeften.

At 4.05 p.m. communications with the outside world were restored.

Thrown once again into doubt and confusion by Keitel’s blunt assertion that Hitler was alive, the timid Olbricht had returned to his office with the news that Fromm would not sign the Valkyrie order, to find that the more resolute Mertz was already going ahead with the issuing of the orders for Valkyrie II, beginning with the bald and bold words: ‘The Führer Adolf Hitler is dead!’ Mertz was actively deploying his forces – he had summoned junior officers who were party to the conspiracy to carry out their allotted roles. Captain Friedrich Karl Klausing, the adjutant who had accompanied Stauffenberg to the Berghof and Rastenburg on 11 and 15 July in Haeften’s absence, was on his way to secure the Berlin army headquarters. Similarly Major Egbert Hayessen was on his way to the office of the capital’s city commander, General Paul von Hase, to take control there. A clutch of young officers – Georg von Oppen, Ewald Heinrich Kleist-Schmenzin, Hans Fritzsche and Ludwig von Hammerstein – had been summoned from the Esplanade Hotel where they had been waiting to act as adjutants in the Bendlerstrasse. Generals Beck and Hoepner, in civilian clothes, had also arrived in the building, and changed into their uniforms – Hoepner using Olbricht’s office toilet for the task. All now awaited the arrival of the main actor: Stauffenberg.

Although Mertz had bounced him into action, Olbricht still fussily wanted Fromm to lend his authority to the orders that were already going out under his name. He therefore returned to his superior’s office, again asserted that Hitler was dead, and informed Fromm that the orders for Valkyrie II were going out. Furious, Fromm leapt to his feet and demanded to know who had given such an order without his authority. Olbricht replied that Mertz had done so, and when he was summoned, Mertz coolly confirmed it. ‘Mertz! You are under arrest!’ Fromm barked. It was 4.30 p.m.

Just at that moment, Olbricht happened to glance out of a window overlooking the courtyard, and was intensely relieved to see a staff car pull up and the unmistakable tall figure of Stauffenberg emerge. Stauffenberg rushed upstairs to Olbricht’s office for a hurried consultation. Hitler was certainly dead, Stauffenberg assured the doubting Olbricht, and seeing that the general was still dubious, added the forgivable exaggeration: ‘I saw them carrying out his body myself.’ Told that Keitel had explicitly denied it, Stauffenberg blurted irritably, ‘Keitel’s lying as usual!’ – a message he would repeat to the growing number of doubters as the long evening unfolded. Other conspirators drifted in – Berthold von Stauffenberg, conspicuous in his blue navy uniform in a crowd of army field grey; Fritz-Dietlof von der Schulenberg; Lieutenant Kleist-Schmenzin and Captain Fritzsche. Stauffenberg repeated the same message to them all: the bomb had killed Hitler, and he had seen his body; he compared the explosion to the detonation of a 150-mm shell. Then Stauffenberg got on the telephone. His first call was to Helldorf, chief of the Berlin Police, summoning him to the Bendlerblock to ensure that he would arrest key members of the SS and Gestapo. Stauffenberg next rang his cousin, Casar von Hofacker, in Paris.

The conspirators in Paris were a small but dedicated group, of which the military governor, General Karl-Heinrich von Stülpnagel, was the titular leader, the equivalent of Beck in Berlin; Lieutenant-Colonel Casar von Hofacker, the only prominent Luftwaffe officer to join the military plot, was, like his cousin Stauffenberg, the dedicated driving force. The other leading figures included Rommel’s Chief of Staff, General Hans Speidel, Colonel Eberhard Finckh and Colonel Hans Otfried von Linstow, Stülpnagel’s Chief of Staff, along with a handful of civilian advisers and administrators. Hofacker had kept this small group abreast of Stauffenberg’s previous attempts to kill Hitler earlier that month. On 19 July he had assembled them again in the Hotel Majestic, to advise them that another attempt would be made the next day. Come what may, he said, this time the bomb would explode. Hofacker had no illusions about the chances of success, telling Baron Teuchert, one of his civilian aides, that they had only a 5 to 10 per cent hope of winning through. He added grimly: ‘If this affair miscarries we shall have an appointment with the hangman.’ His forecast was to prove all too accurate.

Colonel Hans Otfried von Linstow.

Stülpnagel, too, was fatalistically clear-eyed about the chances. A blonde veteran of the First World War, and an intellectual with a lively interest in history and culture, he had often come close to despair and resignation after the repeated failures of the conspirators since 1938, but Hofacker’s iron will had pulled him back into line. Now the strain he was under was beginning to tell: as his friend and fellow officer, the writer and Great War hero Ernst Jünger, stationed on Stülpnagel’s staff in Paris, observed in his diary: ‘He seemed tired; one of his habitual gestures – he repeatedly presses his right hand against the small of his back, as if to stiffen his spine or thrust out his chest – reveals the sort of anxiety that has taken hold of him, and this can be read clearly in his face.’

Nonetheless, Stülpnagel went through the motions as if 20 July was to be another normal day. At 12 noon he lunched with his staff as usual at the Hotel Majestic. It was noticed, however, that the general was quiet and abstracted rather than his usual chatty, witty self (as he was when his tongue was loosened by wine). Those present all agreed later that his mind appeared to be on other things. At 2 p.m. Stülpnagel made an excuse and left the table. Soon after he was observed pacing the Majestic’s roof garden. At 3 p.m. his staff convened a previously scheduled meeting with French officials to discuss the question of housing French refugees from the Normandy fighting. Then the phone in Hofacker’s office rang – it was Stauffenberg calling from Berlin.

His cousin gave Hofacker the same urgent message he had broadcast around the Bendlerblock: the bomb had exploded, Hitler was dead, the Valkyrie putsch was underway and government offices around Berlin were being occupied by troops under the plotters’ orders. Now Hofacker had to do the same. Eyes gleaming with excitement, Hofacker slammed down the phone and rushed to tell his aide Teuchert, calling him out of the refugees’ meeting to say: ‘Hitler is dead! The explosion was frightful!’ He then hurried off to tell Stülpnagel the good news. Teuchert, dazed with joy, reeled off down a corridor where a civilian greeted him with the Nazi salute and the obligatory ‘Heil Hitler!’ Hardly able to contain himself, Teuchert burst into hysterical laughter, leaving the civilian staring, aghast and open-mouthed.

Stülpnagel had just received confirmation from Berlin of Stauffenberg’s message: the codeword ‘Übung’ (‘Exercise’) was the agreed signal that the assassination had been effected and that the Paris Wehrmacht now had to put Valkyrie into effect in the French capital by arresting all the SS and SD personnel in the city. Quickly, Stülpnagel gathered his available officers together in his office – both those involved in the plot, and those not in the know. His secretary, Countess Sophie Podewils, arrived back in the office from a dental appointment in the midst of all the activity. Her boss, wishing to shield her from the danger of too much knowledge, told her that the fuss was about the latest unacceptable demand from Fritz Sauckel, the Nazis’ labour minister, for yet more French workers to prop up Germany’s sagging war economy.

Stülpnagel got to his feet and addressed his visitors: ‘There has been a Gestapo putsch – an attempt on the Führer’s life. All the SS and SD men here in Paris must be arrested. Do not hesitate to use force if there is any resistance.’ Stülpnagel called General Baron Hans von Boineburg-Langsfeld, the monocled commander of troops in Paris, over to his desk and spread out a map showing the locations of all the city’s SS and SD units. ‘They must all be rounded up,’ he repeated. ‘Is that quite clear?’ ‘Perfectly clear,’ Boineburg answered with a click of his heels. The Paris end of Valkyrie was underway.

Still in blissful ignorance of what was going on in Berlin and Paris, Hitler’s staff at Rastenburg, recovering from the initial shock of the bomb, hastily made preparations for the visit from the Duce – Benito Mussolini. As they awaited his belated arrival at the Rastenburg railway siding, Germany’s leaders congratulated their Führer on his ‘miraculous’ escape from Stauffenberg’s bomb blast. With the exception of Goebbels, who was at his Propaganda Ministry in the capital, and Himmler, who, promoted to Commander-in-Chief of the Reserve Army in place of Fromm (who was believed to be in league with the plotters), was flying towards Berlin in pursuit of Stauffenberg, most of the top Nazis had gathered at the Wolf’s Lair. Goering was there – gaudy as ever in his outsize Luftwaffe uniform and jackboots. Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop had hastened over from his Schloss at Steinort to offer his unctuous congratulations to his master. There too was foxy-faced Admiral Karl von Dönitz, overlord of the U-boat campaign against Allied shipping and one of the Reich’s rising stars.

At 4 p.m., some three hours behind schedule, Mussolini’s train rolled into the siding. The former dictator, inappropriately swathed in black coat and hat against the humid heat, looked all of his sixty years. Hitler, however, looked even worse. White-faced and shaken, his singed hair – ‘sticking up like a hedgehog’ as one of his secretaries recalled – was concealed by his military cap. His arm in a sling under his military cloak, and with cotton wool sprouting from both of his injured ears, he presented a sorry sight to his comrade-in-arms. Ushering Mussolini into his car for the short drive back to the nerve-centre of the Wolf’s Lair, Hitler explained in a few words what had happened just three hours before.

Mussolini was greeted by Hitler on 20 July after his train arrived at Rastenburg.

Hitler with Goering and Goebbels.

Aghast that Hitler’s security had been so easily penetrated, Mussolini allowed himself to be given a conducted tour of the shattered remains of the conference room with Hitler as his guide. ‘I was standing right here, next to the table,’ recounted the Führer hoarsely. ‘The bomb went off just at my feet! Look at my uniform!’ he urged as his tattered and scorched garments were held up for the Duce’s inspection. ‘Look at my burns!’ he exclaimed. Hitler then fixed his fellow dictator with one of his famous hypnotic gazes. ‘When I reflect on all this, Duce, it is obvious that nothing is going to happen to me. It is certainly my task to continue on my path and bring my work to completion.’ Recalling his previous escape from Elser’s bomb, Hitler commented that it was not the first time that Providence had held its protective hand over him. ‘Having escaped death in this extraordinary way, I am more than ever sure that the great cause that I serve will survive its present perils and everything will be brought to a good end.’ He gazed at Mussolini, as if beseeching confirmation. Obediently, the Duce answered the Führer’s cue: ‘You are right, Führer,’ he affirmed. ‘Heaven has helped protect and defend you. After this miracle, it is inconceivable that our cause could come to any harm.’

Hitler shows the bomb damage to Mussolini three hours after the blast.

The two dictators and their respective entourages – which included on the Italian side Marshal Graziani, one of the few Italian military leaders to stay loyal to the Duce, and the dictator’s son Vittorio; and on the German side Goering, Dönitz, Ribbentrop and the omnipresent Martin Bormann – then adjourned for tea at 5 p.m. before settling down for their formal talks. The discussions had been due to cover such subjects as the defence of Italy’s Gothic Line against the steady Allied advance up the peninsula, and the fate of thousands of Italian soldiers who were reluctant to fight further for their sawdust Caesar and were being held in deplorable conditions in German camps. The meeting was, however, entirely overshadowed by the repercussions of Stauffenberg’s bomb.

Hitler massages his injured arm after the bombing. (Left to Right) Keitel, Goering, Hitler and Bormann.

With communications with the outside world having been restored, it was becoming all too apparent at Rastenburg that Stauffenberg’s attack had been part of a much wider conspiracy. Anxious inquiries as to whether Hitler was really dead were flooding in from German army bases where the Valkyrie orders had been received, along with confused reports of unauthorized troop movements in Berlin, Paris, Vienna, Prague and even occupied Norway. These all showed that Valkyrie was underway, and that under its cover some sort of attempted putsch was in progress. Hitler himself appeared distracted over his tea, fiddling with the multi-coloured array of pills prescribed for his various ailments by his quack physician Dr Theo Morell, and occasionally swallowing a lozenge in-between his favourite cream cakes. As messengers scurried in and out with news of the condition of those injured by the bomb, or reports of what was going on in the rest of Germany and Europe, the Führer remained silent and strangely abstracted.

The awkward hiatus was filled with interjections from the competing Nazi bigwigs around the table, who, much to the embarrassment of their Italian guests, began to squabble and shout one another down in their protestations of loyalty, indulging in ever more accusatory finger-pointing as they endeavoured to apportion blame for the bombing. Goering opened the attacks, opining that the true reason for the recent reverses in Russia was now all too obvious. ‘Our brave soldiers have been betrayed by their generals!’ he cried, before asserting that his loyal Luftwaffe could and would save the day. Not to be outdone, Dönitz chimed in, protesting the navy’s utter loyalty. The U-boat packs would yet strangle Britain’s sea lanes, he pledged. Ribbentrop and Bormann added their voices to the chorus: the one claiming that Germany’s deteriorating international position could yet be restored by the efforts of his diplomats; the other assuring his boss that the Party, purged of all disloyal elements, would re-double its efforts to win the war on the home front.

In the face of this mix of boot-licking and mutual recrimination, the presence of the embarrassed Italian visitors was apparently forgotten. ‘We noted a growing reciprocal animosity, as if each of them intended to accuse the other of having protected or allowed the plotters to act,’ recalled Filippo Anfuso, Mussolini’s ambassador in Germany. ‘For us Italians it was all frankly unpleasant and disturbing . . . at a certain point Mussolini looked to me as if to ask what we should do.’ As the chorus of loyalty descended into a babble of shouted mutual hatred, with Goering and Dönitz attacking each other for the shortcomings of their respective services, and Goering screaming at Ribbentrop that he was just ‘a failed champagne salesman’ before threatening him with his brandished Reichsmarschall’s baton, the appalling animosities at the heart of the Reich were laid bare for all to see. They were fighting like rats in a sack.

Suddenly, Hitler awoke from his trance. Roaring and spitting, he ignored his squabbling underlings as he unleashed the full force of his fury against the ‘miserable traitors’ who had dared raise their hands against him. He vowed a fearful vengeance against them – and their families. ‘They have deserved ignominious deaths and that is what they will get,’ he hissed. ‘This nest of vipers who have tried to sabotage the greatness and grandeur of my Germany will be exterminated once and for all.’ It was a pledge that he would carry out to the last, terrible letter. As Mussolini took his leave from his partner in crime for what would prove to be the last time, he must have been full of foreboding for the fate that lay in store for them all.

Back in the Bendlerblock in Berlin, even more dramatic scenes were taking place. Stauffenberg headed a delegation of conspirators who marched into Fromm’s office at about 4.45 p.m. Olbricht informed Fromm that he now had confirmation from Stauffenberg – who had been at the scene himself – that Hitler was dead. Stauffenberg agreed – indeed, he added, after witnessing the explosion he had seen Hitler’s body being carried away with his own eyes. Fromm responded that he had spoken to Keitel, who had assured him that the Führer had been only slightly hurt and was definitely alive. ‘Keitel is lying as usual,’ repeated Stauffenberg. Fromm commented that someone in Hitler’s entourage must have been involved, to which Stauffenberg responded quietly: ‘I know that he is dead because I placed the bomb myself.’

Apparently thunderstruck, Fromm exploded. With real or feigned rage he stormed that Stauffenberg had committed high treason as well as murder and must take the consequences. He asked if Stauffenberg had a pistol and would know what to do as a German officer. Stauffenberg coolly replied that he was unarmed, and that in any case he had no intention of committing suicide. Fromm turned to Mertz von Quirnheim and told him to fetch a pistol, to which Mertz pointed out that as the general had recently put him under arrest, he was unable to fulfil that order. At this point, the burly Fromm squared up to the tall Stauffenberg with red face and raised fists, bellowing that he was under arrest along with Olbricht and any other officer involved in the plot. Stauffenberg, despite all that he had already been through that day, remained calm and collected. On the contrary, he told Fromm, it was he who was under arrest.

Alerted by the commotion, Haeften and Kleist-Schmenzin came in from the adjoining map room, and Kleist-Schmenzin pushed a pistol into Fromm’s substantial belly. Accepting the inevitable, Fromm said that he considered himself relieved of his commission by force and asked to be given a bottle of brandy to console himself. He was placed under guard and locked in the office of his adjutant, Captain Heinz-Ludwig Bartram. Hoepner, an old friend of Fromm, was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Reserve Army in his place by his fellow conspirators. He went along to the office to console Fromm, who told him: ‘I’m sorry, Hoepner, but I can’t go along with this. In my opinion the Führer is not dead and you are making a big mistake.’ Hoepner disconsolately trailed back to the others to relay Fromm’s request to be allowed to go home.

Although this request was denied, there was an air of laxness at the Bendlerblock that typified the haphazard, almost half-hearted nature of the operation. At that stage, resolute action might still have saved the day, but confusion, timidity and irresolution ruled in the offices and corridors where the seconds were ticking away and control of events was slipping irresistibly away from the conspirators. Hans Bernd Gisevius, although not an officer, had always been clear that forceful action – up to and including the violent deaths of their Nazi enemies – was the only policy that would bring success. Arriving in the Bendlerblock, he was horrified by the slackness he saw all around him, which even seemed to be infecting Stauffenberg himself. Forgetting rank and decorum, Gisevius fired off a series of questions at a harassed General Beck, to which there were no satisfactory replies: Why was Fromm not shot at once, rather than merely locked in an office? Why was Goebbels still at large in his Propaganda Ministry, doubtless already busily organising the Nazi fightback? Had the radio station been seized? Or the Gestapo headquarters? Why were there no troops defending the Bendlerstrasse itself? The old general’s hesitant, equivocal replies told their own story.

Right on cue, as if to demonstrate the conspirators’ helplessness, the door was flung open and an SS Oberführer (colonel), Humbert Piffraeder, in full black uniform and flanked by two plainclothes Gestapo detectives, marched into the room. Piffraeder had been directly tasked by Himmler to detain Stauffenberg and, missing him at Rangsdorf airport, had followed him back to the Bendlerblock. Clicking his heels ‘like a pistol shot’ and giving Gisevius the Hitler salute, he demanded to speak to the colonel about his activities at Rastenburg. Piffraeder was speedily disarmed and he and his accompanying policemen joined Fromm and other loyalist officers in the plotters’ ‘bag’. Outraged at such softness, Gisevius turned to Stauffenberg, demanding to know why the SS man had not been shot out of hand. Stauffenberg assured him that he would be ‘dealt with’ later, and agreed to consider Gisevius’s suggestion that a hit squad of young officers be formed at the Bendlerstrasse to shoot Goebbels and any SS leaders they found at large. But meanwhile he turned to what he considered the more urgent task – shoring up Valkyrie.