2 Painting the World in Colour

• Defining the cinematographer

• Pioneering Technicolor

• Wings of the Morning

• Henry Fonda

• Punching His Majesty: The Coronation of King George VI

• Count von Keller and World Windows

• To War …

• Western Approaches

‘Western Approaches represents one of the greatest achievements of Britain’s wartime filmmaking. Its compelling story and determinedly documentary approach are immeasurably enhanced by Jack Cardiff’s Technicolor camera work, most of it secured in extraordinarily difficult circumstances.’

Roger Smither—Keeper, Film and Video Archive, Imperial War Museum

JBPerhaps this would be a good time to ask you to define the job of a cinematographer.

JCWell, it’s quite a complex situation: the cinematographer is engaged to photograph a film, but he certainly doesn’t decide what to shoot; that is decided by the director, who has already worked it out from his script. The cinematographer then works with the director to achieve an atmosphere—poverty or high gloss or whatever. It is up to the cinematographer to use his skills to produce that result. Of course, the closer the cameraman works with the director, the better the results will be.

I forget the name of the film, but there was a director on location who saw clouds scudding across the sky and the light was going in and out with impossible contrast. The cameraman said that he couldn’t shoot under those conditions and the director insisted that it was a lovely effect and he wanted the scene shot like that. The cameraman shot the scene as instructed, but he wrote on the numbers board, ‘Shot under protest’. It turned out to be a brilliant sequence and the cameraman won an Oscar. So that explains how the situation works; there has to be mutual trust and cooperation.

JBIt often sounds more complicated than it should because the terms cameraman, cinematographer, director of photography and lighting cameraman are all bandied about. In fact, they are virtually interchangeable names for the same thing, right?

JCYes, there is really no difference. When I first started out, the cameraman did everything; he did all of the lighting and he operated the camera, there were no pure operators. Then, of course, the lighting became much more complicated and there was no longer time to operate the camera itself.

However, even today, some cameramen like to operate themselves. This I will never understand because you have to do so much when you are lighting and you are thinking about that all of the time; you don’t have time to physically prepare and work on the camera. A camera operator pans the camera with great finesse; he is trained to make lovely movements. If I were a cameraman and were operating the camera, I would be concentrating so hard on the movements that I wouldn’t be able to notice if someone had missed a light or something. I could never do it.

With a cameraman who is just starting and who perhaps doesn’t yet have a big reputation, it is tough if he is asked to make things look lousy and dirty, because in his heart he will want to brighten things up a bit. Once you have a big reputation, it matters less if you make some hideous mistake and don’t put a light where it should be. People will still say, ‘Brilliant cinematography—how bold!’ This happens from time to time.

JBWhen did you first become aware of Technicolor?

JCI had just got home after a hard day’s work and my mother said, ‘You had a call and you have to go back to the studios.’ I was pissed off because of the long drive. She said it had to do with ‘Techni-something-or-other’. Of course, Technicolor had never been heard of before, but they wanted to interview all of the camera operators. There were probably half-a-dozen of us working with Korda at the time. I was really angry, but I got in the car and drove back.

When I got there, some of the operators had already been interviewed by representatives from this Technicolor Company and they had been asked the most incredibly difficult questions, about optics and laboratory techniques and terrifying equations. They were literally shaking as they came out.

Well, the same line of questioning happened with me about these theories and equations and I said to them, ‘I think I’m wasting your time because I’m a mathematical dunce and no good at these sorts of things.’ There was a kind of shocked silence and then one of them asked me how I expected to get on in the film business as a cameraman. I told them I loved paintings and that I studied them and I loved light. One of them asked me which side of the face does Rembrandt light and I said, ‘This side, the left, but the other side for etchings.’ All bluff, but I talked about Pieter de Hooch and other old painters and in the end they sent me out feeling rather silly. But the next morning, I was told that I had been chosen. Very weird, having admitted that I was a technical ignoramus, but there you are.

JBWho was on the interview panel?

JCThey were people from the Technicolor Company, not Mr Kalmus who was the big chief, but there was a man called George Kay and one or two others who were the chiefs at Technicolor.

JBWhat were Technicolor doing recruiting in Britain?

JCI never got the full facts, but I think they already had plans for starting Technicolor in England. The idea, officially, was that they wanted to find an operator to make him into a Technicolor cameraman to go to Hollywood. Looking back on it, that didn’t make sense: why an English cameraman? Perhaps there was some other reason … I think that in the back of their minds it must have been that they wanted to open a plant in England.

You don’t make these decisions in a few weeks, it was a long-term thing, and so they were just getting people ready to step into Technicolor. Shortly after that, they did announce that they were going to open up a plant, a laboratory in England, on the Bath Road. And as I had been chosen, I was the first person to be employed by them.

I was very happy, and left Korda—he didn’t seem to mind—and there I was, working full time for Technicolor.

JBBut you still hadn’t laid your hands on a Technicolor camera at this point?

JCNo, what happened next was that they came over with the Technicolor camera, which was amazing; just like the Rolls Royce of cameras. So beautifully made and technically brilliant, running three films at once.

I had an assistant called Henty Creer and he was an old Etonian. A marvellous little assistant, very young, but a brilliant assistant. He didn’t actually work for Technicolor, but he stayed at Denham Studios and worked on the first films with me.

I mention Henty because he was just like a schoolboy and when the war came he worked on the submarines. He actually worked in baby-subs and saw active service, during which he was killed. Absolutely tragic as he was someone that was really making a name for himself.

JBThis all ultimately led to you becoming involved in the first British Technicolor feature film.

JCYes, of course, almost immediately they made Wings of the Morning1 [Harold Schuster, 1937]. Thinking about it, they must have been jolly quick building the laboratory and making that first film. I think they acquired me and then started to build everything else, which must have taken at least six months.

So anyway, I found myself on Wings of the Morning with Henry Fonda and Annabella2 and I had Henty as my assistant. And, of course, Wings of the Morning was made at the Korda studios.

JBWhy was Wings of the Morning chosen as the first British Technicolor film?

JCThat’s one of the things that I shall never really know because these sorts of decisions are made in hotel suites or in the big offices of Mr Korda. The fact was that it portrayed Ireland and gypsies and the Derby horserace, so it was all very colourful.

JBWhat are your memories of the young Henry Fonda on Wings of the Morning?

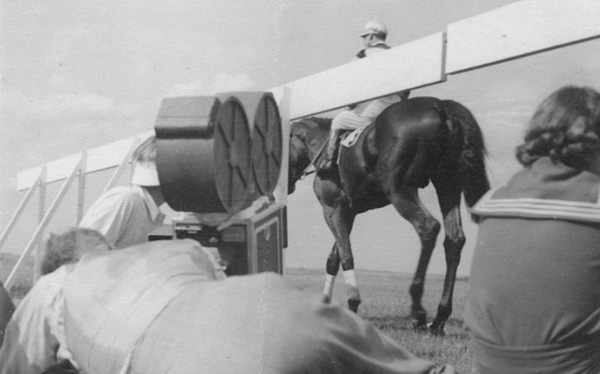

Shooting the Derby horserace finale of Wings of the Morning (1937)

JCHe was a marvellous man to work with, he had a tremendous sense of humour and played tricks all of the time. He was always clowning and if he wasn’t working he would disguise himself: the cameraman would be lighting the set and say, ‘put on number nineteen’, and the light would come on and start going all over the place and then go out … and you would look up and find Henry Fonda working the light!

One time, he pretended to be a madman and rushed through the set in disguise, screaming his head off, and it spread all though the studios that there was a madman on the loose. He was crazy but a very, very good actor. It was a great film to work on.

JBDid Korda have a solid business arrangement with Technicolor at this time?

JCYes, Technicolor right away established themselves, not as a production company to make films, but as a company that studios could hire. Of course, at first hardly anyone would hire them, because it was a very unknown territory.

JBWhat were Technicolor like to work for in those early days?

JCIt became apparent to me quite quickly that Technicolor had very strict rules of conduct and technical abilities. The light had to be exact, because they were running three negatives, each of which had to be perfectly exposed and worked out. You certainly couldn’t be too slaphappy. At first, Technicolor brought over their own cameraman, Ray Rennahan,3 who was a real veteran and obeyed all of the rules. Technicolor wanted light everywhere, because they didn’t like shadows as they didn’t contain controlled colours, and that might affect their prestige. They wanted all of the shadows eliminated.

But Ray lit what I would call very ‘high key’. In other words, lots of filler light everywhere so that there were no black shadows; but then he used cross lights to keep a sort of three-dimensional gloss. He did a wonderful job and I learnt an awful lot from him on Wings of the Morning.

After that, they did a lot more tests, which I worked on and we did some short things. Of course, I was now an operator dying to be a cameraman! That was my great thing. And there were no English Technicolor cameramen, so I was the closest thing as an operator. Even people like Freddie Young had never photographed anything in colour.

JBAnd what kind of technical limitations were you working under with the Technicolor system?

JCThe blimp was just enormous and it was so heavy. We tried to treat it like an ordinary camera, but it was difficult to get lights near, because it was so huge. Also we couldn’t reload the camera because it was a very tricky job that took far too long. We used to haul the camera out of the blimp, put it on a tripod, and replace it with a second, preloaded camera, which would save some time. They were very tricky cameras to work with.

JBDo you recall any rivalry between those pioneering Technicolor in America and those doing so in England?

JCA good question, but as far as I know there was no evidence of any jealousy or rivalry of any kind. God knows what happened. In fact, Technicolor in England had gained a rather enviable reputation, where the Americans thought the colour was so good it must be down to the quality of English water used in the processing. Absolute nonsense, of course!

JBThis sounds like the beginning of a poor vaudeville joke, but you punched King George VI on the nose, didn’t you?

JCBefore the coronation we had this wonderful opportunity to photograph His Majesty the King, in the gardens at Buckingham Palace. Usually you would just have a cameraman and an assistant, but in this case we had to take everybody from Technicolor. We set up the camera where the King was going to come out and it was so rare to get a picture of the King.

When he eventually arrived, he came out with the Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin; I took a tape measure and ran across to measure the distance to him for the focus. We were all very nervous and I ran the tape out far too quickly and hit him right in the face—Bang! There was a terrible silence and I eventually muttered, ‘Ever so sorry, Your Majesty’. He was very sweet, a terribly nice man, and he said it was quite all right.

JBDespite your little faux pas, Technicolor then went on to cover the coronation in some detail.

JCI think we had four cameras in the country at that time. For the great coronation procession of the King travelling through London, each camera had its fixed position, because the crowds were so enormous that we couldn’t move the cameras from one location to another.

So we had these four cameras stationed at the best places. As one of the cameramen, I was perched on a place opposite the Royal Albert Hall on top of a little lodge, at the entrance to the park [Hyde Park]. Once we got up there, we couldn’t move for the crowds, there was no escape. We had to get up there around eight in the morning and there was a rehearsal of all the coaches and the like, including the royal coach. I was pretty high up, so that you couldn’t see anyone in the coach, but it was a lovely shot and I was panning right to left as it went by. It was a beautiful day with the sun shining, so just for fun I photographed it. You couldn’t see anyone inside, so it could have been the Queen of Persia! Then we had to sit down and wait for the real thing and by the time that came along it was pouring with rain, almost impossible to shoot.

When Technicolor saw all of the work the following morning, they couldn’t work out how three cameras had torrential rain and I had wonderful sunshine!

JBThose technical limitations with Technicolor that we have discussed must have really come to the fore on a day like that.

JCYes, because Technicolor, as always in those days, were in terrible trouble without lots of light. George Gunn4 had advanced the idea of shooting inside Westminster Abbey, where there was almost no light; he thought that by cooking up the developer at the laboratory it would be better than nothing. They shot wide open and prayed and it worked. They shot some pretty good stuff. Very innovative stuff.

JBAnother incredibly colourful character entered your life at the same time. Tell me how you first came to meet Count von Keller.

JCWhat happened was that one of the heads of Technicolor, who became a great friend of mine, was Kay Harrison; in fact, he was the chairman of Technicolor. Anyway, one day a man came to see him at his office on the Bath Road. This fellow was very tall, 6 foot 5, and he was a German Count, Count von Keller. He was living in America and was very anti-Hitler, although he had been a General or something in the German army. He was a lovely man to work with. He liked people who worked hard and he liked to play hard.

He told Kay Harrison that he had been all over the world with this little 16mm camera, taking odd pictures here and there, and his friends thought they were wonderful and encouraged him to make a proper series of travelogues using Technicolor. So he was visiting Kay to suggest that he could take a cameraman and put him in the dicky-seat5 of his car with a Technicolor camera on his lap, and they could travel all over the world taking pictures.

JBAn unusual request. What was Kay Harrison’s reaction?

JCKay explained that it wasn’t quite as simple as all that—the camera was very heavy, you required more than just a cameraman with a camera in his lap, and so on. He really explained that it was quite impossible.

JBAnd von Keller wasn’t prepared to forget the idea when he realized how complicated it would all be?

JCTo do him justice and to his credit, no he wasn’t. Count von Keller said, ‘Well, OK, I’ll organize the thing on a bigger scale’—and he did: they became known as World Windows.

He had this 16-cylinder Cadillac and off we went; first to Italy. He had engaged two or three directors, one of whom was Hans Neiter. We ended up with a big truck with all the equipment in: camera dollies and all sorts and it was an entirely new approach to the travelogue. We had such wonderful equipment.

JBBut with all this equipment it must have been incredibly gruelling.

JCOne of the problems was that the camera was still so heavy and we had it on a very light head, which made it difficult to pan or tilt. It was just so top heavy.

JBCan you give me an example of the things that you were filming?

JCOn one of the films in Italy, the challenge was to shoot the interior of St Peter’s in Rome, which is the size of a football field; quite enormous. And still there was the problem of the amount of light required. It needed something like 650 foot-candles at f/1.5, so almost impossible because I was given just six little 2k lamps—absolutely absurd. I had no more than 10 foot-candles instead of the 650 I needed.

So I had this idea: at the back of the Technicolor camera, there was a small hole with a handle in it, which you would use to wind the film on when you were loading it. So I figured I could use this, and if I turned it very slowly, I could crank the film through and make an exposure of some kind. So I did this and it took forever, and having shot about 15 feet of film, I stopped and took the belt off of the camera and put it on the other side of the magazine so that I was exposing the same film in reverse. I did that two or three times at least, until each frame would have had about 1/2-second exposure in total. It was a real gamble, but it was perfect—absolutely marvellous. I suppose I was the first person ever to shoot the interior of St Peter’s, certainly in colour.

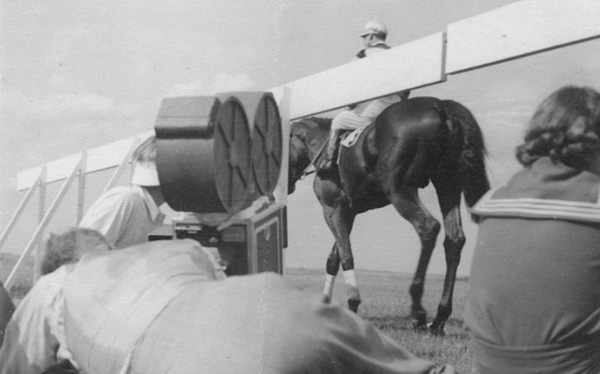

Jack Cardiff during his travels for World Windows

JBHow long did you have to wait to get it developed to find out if the gamble had paid off?

JCIt took several days to get the stuff off to England and then they reported back that it was OK.

JBWhere else did the World Windows take you?

JCAfter Italy, Count von Keller told me he had plans to go to Palestine, so off we went. That was unfortunate because that was when the troubles were really just starting and we had a lot of problems there. I was invited to dinner one night and my hosts called me just before I left my hotel to say, ‘Please don’t come, our daughter has just had her throat cut.’ Terrible things were happening.

So Palestine was quite an experience, but we shot several pictures there and then we went out to India and then Egypt and Africa. They really took me all over the world.

JBYou shot a lot around Petra.6

JCThat was truly wonderful. A difficult place to get to then, and for the last part of the journey you had to go by horseback. Now I think you can go by plane to the best hotels, but when I went, there were no hotels or shops, just some tents—it was so far off the beaten track. Getting into Petra was amazing, riding through this narrow gorge at least 80 feet high and you could look up and just see this slit of sky above you. On the right-hand side you would occasionally see Roman pipe-work, then suddenly you see this fantastic sight: a building, almost like a church,7 carved out of the rock all those years ago.

JBHow long did you spend there?

JCWe photographed the whole thing over about three weeks. On one occasion, I had an idea: when you looked around, you didn’t always notice at first the steps or buildings carved from the rocks, so I suggested we did a ‘double take’, where we panned across something and then whipped back to it. That worked very well.

Another building couldn’t be seen when you were low down, because of this little mound, but as you went up, it was slowly revealed. We didn’t have a crane to lift the camera up with, so I had two tent poles lashed together with ropes, and by pulling the ropes, it raised the camera. A perfect crane shot.

JBPeople from the local Bedouin tribes were still living within Petra at that time?

JCThere were no tourists then, so yes. I would hate to go there now. I was on horseback all the time then, and we used the local Bedouin to help move the camera and things around.

JBYou didn’t have the relative luxury of a three-day turn around to see your film at this point?

JCNo, no, a little longer than that! But a fantastic place to work. ‘A rose-red city, half as old as time’, as the poem has it.8

JBDid you go to Wadi Rum, immortalized by Lawrence in The Seven Pillars of Wisdom9 and later used by David Lean when shooting Lawrence of Arabia [1962]?

JCNo, I wish we had. We didn’t go there because we had a pretty strict schedule and after Petra we had to head off again. It was a wonderful time to visit and I’m quite sure many of these places are ruined now by tourism.

JBWas von Keller financing all of this himself?

JCYes, but the films were done for United Artists. United Artists released them and they were very popular and hugely successful. We did make some marvellous pictures, particularly in India and Egypt.

JBWhat were you shooting in Egypt?

JCWell, the usual stuff: we had shots of the pyramids and all the usual things and we also went down to Aswan.

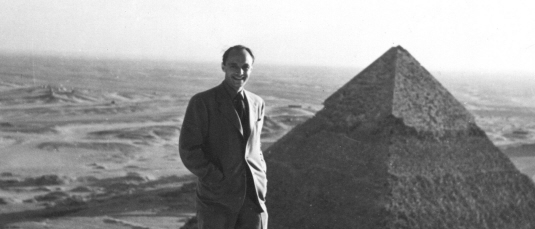

JBYou told me that you came close to capturing the pyramid climbing record.

JCOh yes! That was actually at a later time in Egypt. While I was waiting around, I used to practise jumping up the pyramids. Each stone is at least four foot high, so you have to do a kind of bounding heave-ho to get up each one. I was told that the world record was nine minutes and I did it in 12, which wasn’t bad. If I tried it now, I would take about two days!

JBWhen did you last visit Egypt or Jordan?

JCIt was quite some years ago that I was in Egypt last. It was for a film, Death on the Nile [John Guillermin, 1978]. We had to climb up the pyramids again for that!

JBHow was von Keller getting permission to shoot in all of these places?

JCDon’t forget that at the time we were going around with von Keller, it was still the days of Empire. We didn’t really have to satisfy the locals in most of these places.

His plea to us as his team was that he wanted us to work very, very hard; often late at night or through the heat of the day—however long it takes. But he told us that when we finished it, he promised we would have a ball: parties and as much fun as we liked. That was a great system. We did work jolly hard and shot some great stuff, and when each film was finished we had wonderful parties with dancing and swimming everyday. It was a wonderful time in my life.

JBThe outbreak of World War II obviously ended this chapter in your life.

JCYes, a very sad thing obviously, and I didn’t keep up any correspondence with the Count. He really liked adventure, you know, to head off into the desert. It was certainly more interesting than the usual travelogue because we really got inside our subjects and got to know the people. The films are very difficult to get hold of now; perhaps one or two people have a few copies.

So yes, then came the war. I suppose one might be ashamed, but I’m not ashamed: I had just got married, I had a great career and the idea of going off to war and not coming back really wasn’t on.

Jack Cardiff climbs the pyramids for World Windows

JBSo what happened to Technicolor and your role with them during the war?

JCI thought I would be called up at any minute, but it turned out that Technicolor could be of great use in the war effort. The manager of the department was George Gunn and he had an invention where they used a huge dome and they could project the trajectory of bombers as if they were going across the sky so that the young trainee pilots could practise tracking and firing at them. It was a brilliant thing; I believe George Gunn was decorated for that.

So rather than Technicolor being dropped until the war was over, it actually became an important part of the effort. At the time, I was working with Geoff Unsworth,10 who later became a very big cameraman, and Chris Challis was my assistant. We had a lot of technical work to do. I had to go out and photograph machine-guns being fired at a railway sleeper positioned right next to the camera to make it seem almost as if they were being fired directly into the camera. I was protected as much as possible, but it was truly terrifying. We also had to go on ships and film explosive and shell tests. All sorts.

JBWhat were you doing at sea?

JCThe Germans had this bomb that was attracted by noise at sea and if a cargo ship or whatever was going along, the noise of the engine would attract it. The antidote was so simple it was wonderful. There would be a trailing cable behind the ship, maybe a hundred yards long, and at the end of it was something that made a lot of noise and that would attract the bomb instead of the ship. So we had to photograph that working.

JBThese were mostly reconstructions I assume?

JCWell, we would photograph our own ships, of course, and in this case we also had our own bomb, and that’s what we would use. No point in waiting for the Germans to come along!

There were lots of things like that. We also did quite a bit of aerial work. I flew over various parts of England and photographed the ground to see how good the camouflage was. So a very busy time, but I was still yearning to photograph a feature film.

JBWould you have been freed up to go and do that?

JCOfficially I couldn’t work on a commercial film, because I was working for the Government at that time, and if I left to work on a commercial film, I would be liable to be called up. So I stayed, doing things for the war effort.

Sooner or later a film did come up, though, The Great Mr Handel [Norman Walker, 1942]. This was with Claude Friese-Greene,11 whose father had arguably invented the film camera. He was the favoured cameraman of Norman Walker, who wanted him to photograph this, his first venture into colour. But Friese-Greene said he didn’t know anything about colour and didn’t feel he could do it, so Technicolor suggested me. Captain Walker remembered me because I had been a numbers boy on some of his pictures, including The Hate Ship [1929], and he still thought of me in that role. So he was insisting on Friese-Greene. In the end, Friese-Greene suggested that they let me shoot the first couple of weeks while he watched me and then he would take over once he had learnt enough to carry on. So that was my first break and that ended the stalemate.

Around this time. the MOI, Ministry of Information, decided to do their big first feature in colour, Western Approaches [1942].

JB Western Approaches was their tribute to the Merchant Navy, which you shot for director Pat Jackson.12

JCYes, it was. It certainly wasn’t easy because we were being bombed most of the time. But the MOI wanted to do it, and although they wanted to use their own cameramen, it was pretty obvious that they couldn’t, as they had never worked with colour. I was the only one that could do it. So I came on to this film, which was scheduled to be completed in eight weeks, but ended up taking almost two-and-a-half years to make.

I was the only person for the job. Arguably Friese-Green could have done it, but he was rather large and probably wouldn’t have fitted in the lifeboat.

JBTwo-and-a-half years working continually on that one project?

JCYes, the lifeboat sequence alone was six months shooting. We sat in a lifeboat and I was seasick every day—I never did find my sea legs. In the lifeboat, it was very cramped: we had the camera on a platform that slid between grooves up and down, and we could move the platform from side to side, so we could get any position. You couldn’t take it apart because the sea was rolling like mad. I tell you, the Irish Sea in the winter is diabolical. Even some of the seamen were sick, but Pat Jackson never was.

It is difficult to be creative when you are sick all the time, but we spent six months in this bloody lifeboat in the Irish Sea.

JBBut not just in the Irish Sea …

JCNo, finally we went to America in a convoy of, I think, 110 ships. We went to New York and spent a few days photographing things there. Coming back, we left around 8.30 at night. We had a young Irish boy who used to bring us news and he used to knock on our door and we would let him in, if we weren’t unloading film. But on this occasion we were unloading and he was banging on the door. Suddenly we heard an explosion and we quickly put the film into cans and rushed out. The whole sky was red. I saw a ship going down with two full trains on it and six Sherman tanks, all disappearing under the sea. There were people in the sea and bangs all around—it was terrible. We thought we were going to die.

The ship ahead of us had been hit and its steering mechanism was gone, so that it was heading round in a circle straight towards us. Our Captain just managed to steer out of the way. Many lives were lost that night.

JBWere you trying to film this?

JCWell, we did a little, but you need so much light for Technicolor and this was at night. Everything was dark except for the red glow in the sky. We did photograph a few bits.

After that, we had help from a couple of ships that came and dropped depth charges, but the noise from those was the most frightening thing of all. It was a terrible noise. We carried on and still had another four nights’ sailing to go. We slept in our clothes, of course. We discovered that our cabin was over the storage area for the 12-inch shells, so we weren’t very happy about that.

JBWho were the intended audience for the film? Was it going to be screened in cinemas for the general public?

JCYes. It was really a documentary to show how brave the Merchant Navy seamen were. It had reconstructions, and started with a lifeboat with 22 survivors in it, and they were trying to get back to England. There was a scene where an injured seaman thought he saw a periscope and no one believes him. Eventually a ship comes into view and they signal to it in Morse just as a U-Boat surfaces. It was a very dramatic story.

JBHow did you get your hands on a U-Boat to use in the film?

JCWell, there was one that had been captured and we begged them to let us borrow it. Finally they gave in and said it would be at such and such a position, tomorrow morning at 11 o’clock, and it would surface 100 yards away. All we wanted was a shot of it coming to the surface, so we got ready hours before and got into position. Suddenly it appears, not 100 yards away but less than 12 yards from our ship. It came straight up and these are big things—the most terrifying thing I had ever seen. We couldn’t possibly shoot it so close and it was a complete disaster. Much later—something like eight months later—the Admiralty gave us permission to try again. So we did finally get our shot.

The cramped conditions filming Western Approaches (1942)

After we got back from New York, we all went out in a cruiser deliberately looking for trouble! We sailed around the Mediterranean hoping that someone would attack us, which was a mad thing to do.

JBWere professional actors involved in this?

JCNo, these were real seamen, not actors. The seamen were supposed to have spent something like 15 days adrift at sea and they had beards of 15 days’ growth. Some of them were quite rebellious and thought the whole thing ridiculous, so they would shave off their beards and we would have to use make-up instead. Everything that could go wrong, went wrong.

We shot one scene in broad daylight, and then when we got to shoot the close-ups, it was raining and dark grey. So I had to light using a lot of tricks to match the shots. I made sunshine with one light by taking off the blue filter so that it became very orange and then overexposed the film and told the laboratory to correct the orange back out of it. That matched quite successfully.

JBWas it difficult to persuade Technicolor to fool around with the process like that?

JCOh yes! To start off, I was the enfant terrible of Technicolor, the real bad boy that broke all of their rules, but eventually they came to appreciate what I was trying to do.

JBDidn’t you lose a camera under water at one point?

JCIronically that was the one shot that we did at Pinewood Studios.13 It was supposed to be inside the U-Boat and they had built a set in the big water tank there. It was halffilled with water and I had an idea that we could start above the level of the water to see the Germans thrashing about, and then I put the camera on a geared head that you could crank down below the level of the water. This was from behind glass in a kind of underwater booth inside the tank. It was less than a yard wide and I was the one in it, perhaps with Chris Challis, and the camera was on a uni-pod so that we could wind it down. The trouble was that the booth was buoyant, and no matter how much weight we put in, it we couldn’t get it far enough under the water.

Finally there was no more room to move inside the booth because of all these weights, so they decided to put planks across the top of it and get people to stand on them. It took about a dozen people on these planks to keep it down and we shot the scene, marvellous, a great scene. Then the assistant director called ‘lunch’, and everyone jumped off the planks. Because of the sudden buoyancy, we shot straight up and tipped over. We were working like mad to get the camera out of the water and it took us a good ten minutes to finally rescue it. It was sodden wet and it was put in a bath of oil and whisked off to the labs. Everything was fine and they were able to print the film perfectly.

JBA modern camera certainly wouldn’t survive that!

JCNo, I would guess not.

JBIt might be interesting to see again. When was the last time you saw Western Approaches?

JCThe film is still in the archives at the Imperial War Museum in London. I can’t think when I would last have seen it. I have probably seen bits of it from time to time. I still see the director, Pat Jackson; we still play billiards together.