MUHAMMAD’S

MOUNTAIN

MUHAMMAD’S MOUNTAIN

FOLLOWING THE EXAMPLE of Elijah Muhammad, Ali runs his house, camp, and office with a combination of discipline, respect, and good humour. His wife Belinda, the austere mother of Ali’s three young daughters and infant son, spends most of her time in their $250,000 Spanish-style home in the fashionable suburb of Cherry Hill, New Jersey, looking after the education of her children, whom she is preparing for formal Muslim schools in Chicago.

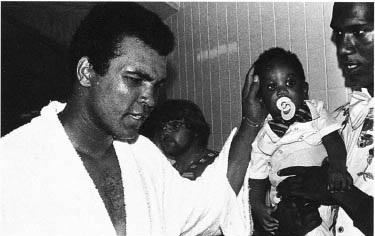

One afternoon, as I am sitting with Ali on half a tree trunk converted into a bench in the courtyard, Belinda emerges from the cabin. She is tall, about 5 feet 11, and fairly slim, and always wears long dresses or skirts that reach her ankles. She often wears sunglasses. Today she is followed by a demure elderly nurse in a white uniform who is leading the children along. As Belinda looks on, the nurse brings little Muhammad over, and his father picks him up. ‘Don’t he look like me?’ Ali asks, beaming. He kisses and hugs the child, who sits happily for a few minutes, cradled in his father’s massive arms. Then he squirms down on to the bench and waddles away. Ali watches proudly as the nurse leads Muhammad back to join his sisters.

Later, Belinda shows some tourists around the camp. Dressed in a long white skirt, she escorts a group of children through the gym and across to Coretta’s kitchen, explaining that Coretta is Ali’s aunt. She laughs at their jokes, smiles constantly, and is a model guide, but maintains a certain distance.

For the past two years, Ali has spent most of his time training for fights at camp, or traveling to fulfill various engagements. Though he spends little time in Cherry Hill with his family, they occasionally visit the camp for a week at a time, and, with his children around him, Ali quickly falls into the role of educator and disciplinarian. ‘I wrote something the other day,’ he says, turning back to us: ‘Do not take an example of another as an excuse for your own wrongdoing. Right? My little daughter Jamillah did something that caused me to write this. She said, “Well, Reeshemah did it. “Why?” I said, “Well, Reeshemah was wrong. You can’t be wrong because she was wrong.”’

Without breaking stride, Ali scoops her up in his arms, shouting, ‘Look at that pretty girl! What are you doing today? How do you feel?’ He hugs her, kisses her, and puts her back on the ground. She smiles up at him.

But as with everything else he does, Ali balances this discipline with plenty of good-natured spontaneity. Later, as we’re walking past the gym, we see Reeshemah talking with a group of other children. Without breaking stride, Ali scoops her up in his arms, shouting, ‘Look at that pretty girl! What are you doing today? How do you feel?’ He hugs her, kisses her, and puts her back on the ground. She smiles up at him.

In camp, the people closest to Ali are cornerman and court jester Bundini Brown; Angelo Dundee, his trainer; Blood, his second cornerman; and Gene Kilroy, who looks after his practical daily affairs. Again following the example of Elijah Muhammad, Ali is very much in charge of his entourage and, though no one is put into the position of being a ‘yes’ man, everyone is subjected to Ali’s rigorous discipline at one time or another. He has a poem that goes:

Destiny

Destiny can take your best friend

As an instrument to cause you harm

And your worst enemy to do you good.

Reading it, he adds: ‘Right? Judas betrayed Jesus, and Malcolm X betrayed Elijah Muhammad. I just fired two fellers who were with me for a few years. Then there are some people who didn’t used to like me; now they say: “You know, I been watching you. I like you now.” One time I couldn’t fight in this country. One time I couldn’t box nowhere. Now they beg me to come. T.V. nation-wide shows. They name fights after me. Destiny caused this, see? Isn’t that beautiful?’

Bundini, Angelo, Blood and Gene respect Ali with an emotional loyalty no argument can crack. They have stuck together for a long time, through many trials, and they would not have stayed on if anything else meant more to them. At camp, they live together in the fourth cabin, dug into the hill above the courtyard.

Bundini Brown saunters around the corner of the gym and heads across the courtyard wearing a Hawaiian shirt and tight small red woolen cap, his thin legs clad in yellow cotton trousers. He moves with the authority of a man who is used to being watched. Suddenly Blood steps quietly out from the shadows of the kitchen wall and says something under his breath.

‘What you say?’ Bundini snaps, tensing just noticeably under the graceful swagger.

‘When you live on the hill, you live by the rules of the hill,’ Blood snarls. ‘You were in later than eleven last night.’

Bundini turns around quickly and walks off up the hill, muttering to himself; Blood follows him resentfully with his eyes. Ten minutes later, Bundini emerges from the cabin with a sheaf of papers in his hand, talking to a young aide; they walk slowly down the hill. Halfway down, Bundini stops, wags his finger angrily at the young man, then turns and walks back uphill quickly, glancing over his shoulder with a threatening look to make sure that he will be obeyed. The aide stares helplessly at the ground.

Other things mark Bundini. As Ali’s court jester and cornerman, he works hard at both jobs and has been irreplaceable. His casual style reminds you that the regimentation of camp life has its necessary exceptions. Outside camp, Bundini keeps himself busy by devoting his considerable talents and energy to such diverse activities as writing (he is currently working on a book called Only Human, which is, he says, ‘about people … on this planet’), travel, and films (he appeared as the Black Mafia’s right hand killer in ‘Shaft’ and ‘Shaft’s Big Score.’ ‘I didn’t get a chance to show my dimples, though, see? That’s the only thing I didn’t like about it,’ he says).

Bundini appeared as the Black Mafia’s right hand killer in ‘Shaft’ and ‘Shaft’s Big Score’. ‘I didn’t get a chance to show my dimples, though, see? That’s the only thing I didn’t like about it,’ he says.

I’m lounging around the gym, talking with a television crew, when Bundini angles in, smiling behind a pair of thick brown-framed glasses, to start a game of craps. Soon the dice are rattling to the rhythm of Bundini’s hypnotic calls. The T.V. director has lost fifty dollars in ten minutes and tries to back out, but Bundini moves fast, calling three more bets before the director can take his hand out of his pocket. Next Bundini wants me to play, but I start asking questions instead. He says he won’t give me an interview unless I pay him. Offering him supper instead, I keep telling him how great I think he is.

“Paid my rent when I was nine – bop de bop bop bam bam – born on a doorstep with no cross or chair, had to suck the first nipple that came along – bop de bop bop bam bam – never had a diaper service, been around the world twenty-six times …” Bundini Brown

‘Supper?’ exclaims an incredulous Mr. Brown, slapping his ample stomach with one thin hand and staring at me with calm, cocksure eyes: ‘Baby, you know I ain’t hungry. What you want to talk about?’

‘What do you do all the time up here?’ I begin, countering his gaze by hopping from foot to foot. He shifts his attention to a small punching bag just to the right of his head, and begins swatting it rhythmically as we walk.

‘What do I do day by day? (Bop de bop bop bam bam goes the punching.)

‘Yeah.’

‘Be a friend,’ he replies.

‘What’s your reputation based on?’

‘Paid my rent when I was nine – bop de bop bop bam bam – born on a doorstep with no cross or chair, had to suck the first nipple that came along – bop de bop bop bam bam – never had a diaper service, been around the world twenty-six times …’

‘What were you doing before you were with Ali?’

‘I was with Sugar Ray Robinson for nine years,’ Bundini says, dropping his hands. ‘He was something like Ali. Great religious type of thing.’

‘How would you describe Ali to someone who had never met him?’

The answer came back fast and hard: ‘That he’s a prophet.’

‘How about personally, though?’

‘Like a little boy. Find a little boy in a person, you find common sense. Find common sense, you find equal justice among people.’

(Earlier that day, I had been sitting opposite Ali in the kitchen, watching him write a lecture. Bundini was sitting at the corner of the table, reading a magazine. As he finished each sheet of paper, Ali would hand it to me. Occasionally he’d look up, saying, ‘Isn’t this beautiful?’ and read a page he’d just written. Bundini would put his magazine down and – with his chin in his hands, leaning toward Ali – drink in every word.)

‘What did you feel like when Ali read those things this morning?’ I ask. ‘Were you moved by it?’

‘I get moved by the things that I like; some things I don’t get moved by. What I like, he moves me more than the average person do …’ Bundini pauses, gazing straight at me. ‘Otherwise we wouldn’t be together. God put us together; I didn’t get my job from the employment office.’

I throw some more questions at Bundini. Finally he says, ‘You don’t know anything about me, do you?’

‘Oh yeah, I do,’ I protest. ‘I know you have a good sense of humour, you’re not boring.’

‘Right. But I do all that crying all the time. Don’t that mess you up? Why do I cry?’

A door swings open to our right, interrupting the conversation, and Angelo Dundee steps up to have a word with Bundini.

Dundee – a short, inconspicuously dressed man with a reddish toupee and glasses – has been Ali’s trainer for over ten years. He is a soft-spoken, friendly man who seems to be least involved with Ali’s intellectual life, most involved with his training and boxing. His habitual relationship with Ali, tested by many conflicts they’ve withstood together, has developed into a deep trust and easy-going exchange. They move comfortably in and out of each other’s orbits, and if Angelo sets the guidelines for training, he also knows Ali’s judgement is as good as his own most of the time.

After lunch one afternoon, as we’re inspecting the rocks with Ali, Dundee passes by. ‘You gonna lie down, Muhammad?’ he asks.

‘No, not today.’

‘Okay,’ Angelo replies, without a hint of protest. Ali grins and calls after him, ‘I can’t do much layin’ down today, you hear?’

“You gonna lie down, Muhammad?” he asks. “No, not today.”

“Okay,” Angelo replies, without a hint of protest. Ali grins and calls after him, “I can’t do much layin’ down today, you hear?”

Dundee’s view of Ali is completely positive but slightly distanced by a managerial concern over what Ali will do next. Thus when Ali had first suggested the idea of the camp, Angelo had argued against it.

‘You know, I didn’t think he’d stick to it,’ he tells me, carefully drawing a pipe out of his mouth and gazing at it. ‘I’ve seen him pick up so many things with total enthusiasm, only to drop them six months later. I was worried he was going to spend a lot of money on this place and lose interest half way through. And once Muhammad’s lost interest, there’s nothing you can do about it.’ He pauses for a minute to light his pipe. ‘Anyway, Ali didn’t drop it. He’s stuck to it, and it’s already paid off the $200,000 invested. See, when he used to train in Florida his hotel bills were $10,000 a month easy, what with three meals a day and all the rooms and suites he had to rent. He realised he could build himself a log cabin for $10,000. Also he wanted the country air, fresh food and hills to run through. He’s got it all here, and it’s working out fine.’

Angelo is obviously pleased with the camp now, in all its aspects. He is the picture of total dedication – sweeping the gymnasium floor, supervising odd jobs, handling many routine aspects of Ali’s public relations – always with the same concern that the job be done right and on time. Unlike Bundini and Blood, he rarely sits around making Smalltalk.

I’m sitting in the kitchen with Ali and Bundini, talking about a lecture Ali is writing called ‘The Education of the Infant’. ‘The cake sprouted from a hot plate with some grease on it,’ Bundini is saying. ‘You take sugar, eggs, powder, all kinds of things, and when it’s over, it’s one sight and one flavor. You’re looking at a person!’

Ali chuckles. Angelo comes through the door. ‘Is Wednesday okay for the press to come down?’ he asks loudly, interrupting to get Ali’s attention. Ali thinks for a minute: ‘Wednesday’s fine,’ he says, chuckling again and turning back to the conversation. ‘You sure now?’ says Angelo, concerned, walking over beside Ali and placing one hand on the back of his chair. ‘Yeah,’ Ali says, with a touch of impatience. ‘Wednesday’s fine.’ ‘Okay, you got it! You got it!’ sings the ebullient Angelo, walking around the room, straightening a couple of chairs. There is a large ‘No Smoking’ sign in the kitchen, and he has left the perennial pipe outside. ‘Wednesday it is!’ he concludes, heading for the door with another pipe already in his hand.

But if Angelo sometimes seems to create work for its own sake, he too is kept in line by Ali’s firm control over the camp, and is not above taking orders. We’re standing outside by the edge of Ali’s cabin, talking, when Ali suddenly gets an idea. ‘Hey Angelo!’ he calls out, without turning around. Dundee is twenty yards behind him, watering some trash with a garden hose, and doesn’t respond. ‘Angelo!’ Ali calls out again, but Dundee still doesn’t hear him. Ali whirls around, angry: ‘Angelo, come over here!’ he snaps. Dundee looks up, startled, drops the hose, and trots over with a look of deep concern.

Blood keeps a lower profile around the camp than do Angelo or Bundini. He is a retired boxer, and it seems that his respect for Ali is due more to Ali’s physical prowess and professional accomplishments than to his intellectual efforts.

Between training sessions, when he stands by with a stopwatch in hand or rubs Ali’s back and arms with oil, Blood is primarily in charge of seeing that the physical labor around the camp gets done. He presides over a series of jobs with slow, steady thoroughness, only occasionally seeming to betray a touch of insecurity about his role in the group. He enjoys talking to the various sparring partners who regularly appear at the camp, and presides as a dry foil to Bundini’s caustic wit over the dinner table. As he and Bundini go at it from opposite ends of the table one night, a strange, slightly nervous silence holds the room:

‘Look at Blood go! That nigger’s got a hunger!’ Bundini cracks.

Blood puts a chicken bone down on his plate, sits back deliberately and: ‘Your mouth’s so full of nonsense, Bundini, you don’t have room for a meal,’ he says, arching one eyebrow. Bundini grins.

‘You aren’t from Crawdaddy, are you?’ he asks a young reporter one day. ‘Because they wrote a really nasty piece…Talked about the way Ali treated his white lackeys and stuff,’ Gene says, upset.

Blood is clearly, after Bundini himself, the most hard-headed person there, the best friend and worst enemy. He inspires total confidence with his quiet professionalism, his iron strong, slim body and still face. It is easy to see why Ali has him in his corner.

Gene does not quite share the substantially black humor that holds the crew together during the tough months of training, and though he gets along well with everyone, he seems to prefer to sit alone, going over events, answering phones, always worrying.

‘You aren’t from Crawdaddy, are you?’ he asks a young reporter one day. ‘Because they wrote a really nasty piece.’

‘No, I’m not,’ the reporter says. ‘What did they say?’

‘Talked about the way Ali treated his white lackeys and stuff,’ Gene says, upset. Obviously he feels that he has been singled out as the white lackey. He isn’t. ‘I’ve been with Ali twelve years unofficially; four years officially,’ Gene says. ‘I feel like a brother to him. This thing wouldn’t end unless Ali said, “So long.’”

Gene is always busy at Ali’s side in public events around the country. When you see two men holding Ali back in a television studio as he shouts at George Foreman, tearing his jacket off, ready to brawl, the tall white man with thick black curly hair and moustache is Gene. The other man is Ali’s slightly younger brother, Rahmann, also a Muslim, who works full time at the camp as a senior aide and is often quietly at Ali’s side.

Ali expects and gets a high performance from every person he employs. He gets it more because they respect him than because he tells them he wants it, but he isn’t remiss at telling people off. We’re sitting in the kitchen; Ali is writing at one of the tables. Gene comes in with a sheaf of bills in his hand and, crouching down by Ali’s chair, asks him to sign a couple of checks. Ali looks over the bills and, without raising his voice, but with a touch of anger so that he talks faster, snaps: ‘I never ordered those fences. There you go again. I told you: don’t go spending my money without asking me first.’

‘But I didn’t, Ali!’ Gene protests. He looks up, worried, but there is no room for protest. Ali is already writing again.

If anyone from outside the camp criticizes a friend, Ali is quick to come to the defense. ‘I got a saying: Blessed are they who cover the scars of others, even from their own eyes. You’ve got a fault, and the word’s getting out,’ he explains. ‘They say: “You know him. What is it?” I say: “It’s a damn lie. He’s not that way.”

On the other hand, if arguments arise in camp, and if Gene or Angelo gets told off, it’s because Ali feels that it’s his duty, and his alone, to run the camp as he would his own home – in all its aspects, following the example of Elijah Muhammad.

It’s not a matter of any lack of respect. If anyone from outside the camp criticizes a friend, Ali is quick to come to the defense. ‘I got a saying: Blessed are they who cover the scars of others, even from their own eyes. You’ve got a fault, and the word’s getting out,’ he explains. ‘They say: “You know him. What is it?” I say: “It’s a damn lie. He’s not that way.” And yet you are that way, but I’m going to cover you from him. Now I’m trying to forgive you; I’m going along with you. I don’t want to say … See?’

Ali’s relationships with people outside his circle, ranging from the most casual visitor to what he might call his ‘office’ relationships, is another matter altogether. He is rarely, if ever, critical or demanding: quite the opposite. Day after day he will perform tirelessly for visitors – ranging from Elvis Presley and Sammy Davis Jr. to faded Hollywood stars, boy scouts and itinerant hippies – with an inexhaustible good humor.

We’re standing in front of the camp with Ali and Gene. A small group of tourists hovers ten feet away. They’ve come to see the Champ. Ali never ignores them. Today he is sparring with a nine-year-old blond boy, and he pretends to be knocked down. The toupeed father from New Jersey ecstatically films the fight with a small Bolex. As he finishes, Ali takes the youngster by the shoulders and tells him: ‘Now you can tell all your friends that you fought Muhammad Ali and knocked him down. That’ll make you famous!’ He runs into the gym and returns carrying Floyd Patterson’s golden gloves, to show them to the kids.

Another time we’re again standing by the rock in front of the camp, and Gene comes over, followed by a thin, long-haired hippie. ‘Listen Muhammad, here’s a friend of mine,’ Gene says.

‘Yeeeeeeeaaaahh?’ Ali exclaims, bursting into a big smile and laughing as he shakes hands with the young man.

‘He just packed up and left home,’ Gene says, egging Ali on.

Ali gets right into the swing of the situation: ‘You did the right thing! You did the right thing!’

‘You got to be a hippie to make it,’ the hippie replies.

‘You don’t wear no shoes?’ Ali asks, pointing to the hippie’s bare feet.

‘Did till they wore out.’

Ali laughs again. ‘How many clothes you carry with you?’

‘Muh jeans, pants, pair of shorts, couple of shirts.’

‘That’s all, huh?’ Ali asks, acting incredulous.

‘Toothbrush,’ the hippie adds.

‘No kidding. You’re not married? You don’t worry about nobody?’

The hippie draws himself up. ‘I been through them things,’ he says proudly.

‘You walk the highway barefoot?’ Ali asks. ‘You got some shoes, don’t you?’

‘I got a pair of flip-flops for the rocky roads.’

‘Yeah? How old are you then?’

‘Twenty-six. You get used to it, you know.’

‘Yeah,’ says Ali, shaking hands as the hippie moves on. Later, he turns to us: ‘You gotta admire somebody like that,’ he says.

Perhaps the most vivid example I saw of an ‘office’ or ‘business’ relationship was that of Ali and one Harvey Moyer. A certain morning, I came into the gym to find Ali surrounded by eight children – his own and some of the retainers’. They were jumping all over him, running up and down. He was shouting and playing. He waved as I drifted past and took a seat against the wall beside a punching bag. Bundini, Angelo, Blood, Rahmann, Gene, and six younger aides were all there, joking with Ali, relaxing.

‘Come over to the kitchen in about an hour,’ Ali called out. ‘Someone I want you to meet.’

An hour later, I’m walking toward the kitchen. A sedan pulls up nearby and a short, puffy, round white man pulls himself out from behind the wheel. His watery eyes look around anxiously.

The kitchen door opens. Ali leans out and yells, ‘Hey Harvey! Come on in!’ Then he looks at me, winks, and tells me to come in too.

Harvey reaches the kitchen door out of breath. ‘I … know you’re busy,’ he pants to Ali. ‘I … just came up … to look at the bell.’

‘Come on in! Come on in!’ Ali insists, leading us all toward a table. He produces some coffee, and we sit down.

Looking across at me seriously, Ali breaks the silence. ‘A new angle. Now very seriously get this,’ he begins. ‘You got your tape on?’

‘Yeah,’ I admit.

‘Okay. I want you to meet Mr. Moyer. How do you spell it?’

‘M-O-Y-E-R.’ Moyer jerks the letters out, still breathless. I look at him, wondering who he is, why he deserves this big presentation. ‘Moyer?’ I ask.

‘See my bell outside?’ Ali asks enthusiastically, pointing at Moyer. ‘He bought that bell for hisself. And he gave me the bell.’ Ali lets that sink in, but still don’t have the Moyer equation worked out.

‘He paid about $3000 for the bell. He gave me the bell for $1500. The bell weighs how much?’

“Harvey Moyer’s been the biggest thing that’s happened to me since finding this ground. He brought me my rocks; it was his idea, he told me. He gave me the first rock, and he suggested putting Jack Johnson’s name on it.”

‘Seven hundred and fifty pounds,’ the 250 pound Moyer replies from behind a light gray knit shirt.

‘It’s very old and you can hear it all over,’ Ali continues. ‘And it’s antique. Harvey Moyer’s been the biggest thing that’s happened to me since finding this ground. He brought me my rocks; it was his idea, he told me. He gave me the first rock, and he suggested putting Jack Johnson’s name on it. Come on outside, let me show you. Got your camera?’ The three of us get up and walk slowly around the gym toward the entranceway.

‘So how long ago did you first meet Ali?’ I ask Moyer.

Moyer screws up his face. ‘Oh … er … um …’

‘Two months ago,’ Ah interjects.

Moyer nods slowly, thinking: ‘About … two months.’

‘So what inspired you to give him the bell, to bring the bell up here?’

Moyer stares at me as if he doesn’t understand my question: ‘This week er …’

Ali breaks in again, leaning across Moyer: ‘I went looking for bells.’

‘He went lookin’,’ Moyer says, with a resigned nod.

When we reach the rock, Ali directs the pose: ‘I’ll stand with my hand out, and Mr. Moyer will present this rock to me. He gave it to me. He’ll hold his hand out …’

As soon as the appropriate photographs are taken, Ali asks Mr. Moyer to give me his card and makes me promise to send Moyer a copy of the photograph of them by the rock.

‘Are you gonna have a rock with your name on it?’ I ask.

‘The whole mountain will be my rock!’ Ali exclaims, quickly laughing. From that time on, Moyer appeared in the scenario quite regularly.

Another time, Ali took me aside and said, ‘Look, here comes Harvey Moyer. Be nice to him, ’cause it’s his birthday today, you hear? We’re gonna have a surprise party for him later on tonight.’ And there was Moyer, pulling himself out of his car, dropping in to see how construction was going on a cabin. I walked around with him, going over the grounds, checking the foundations of the cabin, looking at a covered wagon frame he’d just delivered.

Moyer never expressed anything but total admiration for Ali. Whenever I was alone with him, he spoke of Ali in quiet amazement, saying things like: ‘I don’t know how he manages to do it.’ To him, Ali is a king whose every whim makes sense and whose wish is a command. He gives Ali priority over his many other, and in some cases larger, customers. I finally asked Moyer exactly what his business was. Ali listened in eagerly as he said, ‘Well, we do almost anything at all. Demolition, putting steel works up, fabricating, dismantling …’

‘Dismantling big machines that take six months,’ Ali added enthusiastically. ‘Those big machines that dig coal. And then you take them to Florida and put them back up. And he’s got cranes. You should see the cranes! He moves mountains!’

Perhaps the camp is so important to Ali that he gives its builder as much attention as a king would give the architect of his castle. It’s more likely, however, that this is simply a good example of Ali’s method of conducting business. He never tires of praising Moyer to anyone and everyone who will listen. In return, Moyer made sure the camp was finished quickly and contributed his considerable local and technical know-how to the project for a very reasonable price. Everyone was happy, and the job got done.