INTRODUCTION

THE FIRST ENCOUNTER

WHEN I FIRST met Muhammad Ali in the summer of 1973 he was thirty-one years old and a bundle of contradictions. While making a point of devoting his life to Black Muslim principles, he inhabited a wealthy home in a white Philadelphia suburb, and money flowed through his hands like water. He was married to his second wife Veronica, a tall, graceful black woman who adhered to his religious principles and had borne him two daughters and a son. Yet his sexual activities beyond the family fold were legend. He bought cars like Elvis; one day I would see him reclining in the back of a white stretch Lincoln limousine, the next he would be stooping into the back of a brand new green Rolls Royce to retrieve a sheaf of papers. He also owned several aeroplanes and maintained a luxurious, privately commissioned touring bus in which he and his entourage often drove to his fights.

In these details, apart from the affiliation with the Black Muslims, his life appeared little different from previous heavyweight champions. However, there was, and is, a lot more to Ali than meets the eye. Although few people knew it then, Ali’s plan, after regaining the heavyweight championship in Zaire in 1974, was to retire from boxing and travel around the world delivering the kinds of lectures and poems that appear later in my book.

Prior to this, some students at Oxford had passed around a petition voting Ali the next visiting professor of poetry. This was the sort of thing the press would jump on, and he would enjoy playing along with. The previous recipient of the award had been W. H. Auden. As Ali explained, ‘They said I only had to go there twice a year to give speeches. The salary couldn’t pay my laundry bills, but a boxer has never been a professor of poetry at Oxford University, so I said I would do it.’

The author with Muhammad in 1973 at the time of the first interview.

At the time I was a penniless poet living in Philadelphia, trying to make a living by interviewing celebrities I thought I could learn something from for national magazines. I wasn’t a committed boxing fan, but, like everyone in the world, I knew Muhammad Ali, had seen him beat Sonny Liston in 1964 and watched him battle his way back as a contender for George Foreman’s heavyweight crown, after having been suspended in 1967 from boxing because of his refusal to be inducted into the army during the Vietnam conflict.

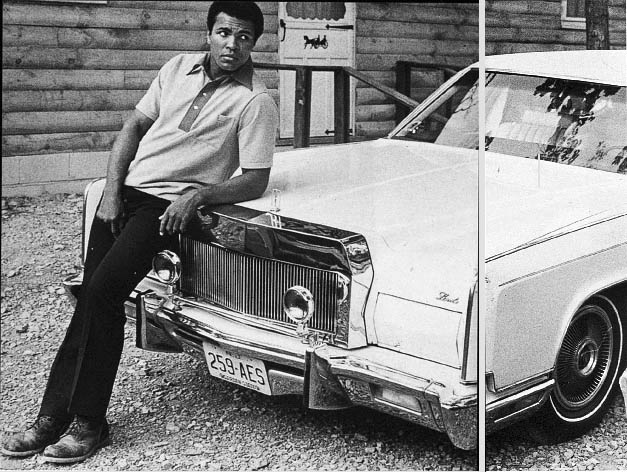

Muhammad in 1973 at Fighter's Heaven with one of his cars

When I read the piece about Ali and Oxford in a local paper, I knew I had found my subject.

Three days after I phoned him at Fighter’s Heaven, his training camp in Deerlake, Pennsylvania, a 1½ hour drive from Philadelphia, I found myself sitting in his log-cabin kitchen underneath a sign saying ‘Don’t criticise the coffee, you may be old and weak yourself one day’.

He was definitely planning to quit boxing and begin the second half of his career. ‘They ain’t seen nothing yet!’ he assured me. ‘They just seen a little boxing. They ain’t seen the real Muhammad Ali!’

Ali was a quick study. He realised within the first hour of our conversation that I was somebody who might actually print what he said, because I seemed, as I was, highly amused by his scintillating talk. He turned our first one and a half hour interview into an eight hour marathon. As we were leaving the kitchen after the first round of taping, Ali shouted excitedly, ‘Wanna go for a ride on the bus?’ ‘Yes!’ I yelled.

One hour later, as the bus climbed back from Highway 61 up Muhammad’s Mountain to Fighter’s Heaven, Ali told me I was the ‘young, white, college educated long hair’ he had been looking for, who could take his message to all the other ‘young, white, college long hairs’. During the late sixties when he was not allowed to box, Ali had made part of his much needed income lecturing at colleges just like Timothy Leary, Allen Ginsberg, Andy Warhol and the other leading counterculture figures. ‘Now,’ he told me, he was getting ready to be the ‘next black Billy Graham’.

As soon as Ali beat George Foreman in the ‘Rumble in the Jungle’, as he was already calling it, and won back the world heavyweight championship, he was definitely planning to quit boxing and begin the second half of his career. ‘They ain’t seen nothing yet!’ he assured me, popping his eyes out in a put-on bug-eyed stare. ‘They just seen a little boxing!’ he shouted. ‘They ain’t seen the real Muhammad Ah!’

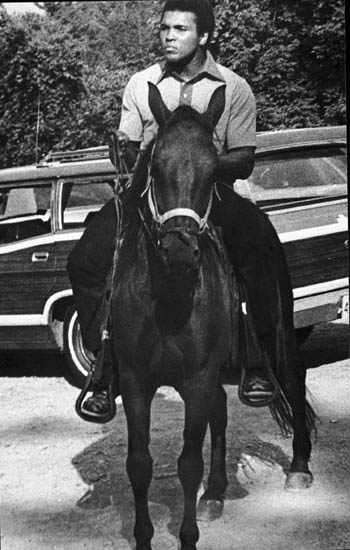

‘Yeah! I ride em, man. I can ride like Roy Rogers! Can I ride? You stick around a little while, you gonna see me ride!’

I was invited to come and visit him at his camp whenever I wanted to. Over the next year I went up there at least ten times, taping on each occasion a conversation with Ali, in between getting to know the other people in his world.

The little book that grew out of those meetings and conversations with Ali was the brainchild of Gerard Malanga, who was an acquisitions editor at the legendary publisher Maurice Girodias’ (Candy, Naked Lunch, Lolita) last publishing venture, the Freeway Press. Malanga had been the first literary figure to recognise Ali as a poet in his 1963 edition of the Wagner Literary Review. Ali: Fighter, Poet, Prophet was published, the very day Ali beat Foreman on 30 October, 1974. We had, of course, the traditional lunch publishers take their authors to on such occasions.

However, Girodias had left his wallet at the office, so I ended up paying for our ‘victory’ lunch with my last fifty dollars. Two weeks later, Freeway Press went bankrupt. Because Maurice had not paid his printer for months, the infuriated man shredded the fifty-thousand copies of my book he had not delivered to the distributor. We estimated that one to two-thousand copies saw the light of day. It was never reviewed.

Shortly thereafter I was personally able to give Ali a box of two hundred copies of the book in his New York hotel, the Essex House, on Central Park South, and walked down the big street with him as he looked through it, surrounded by a screaming, hysterical crowd.

Still, Ali: Fighter, Poet, Prophet held a special place in my heart for the following twenty-three years. It was my first book, my first baby, and I knew that Ali had appreciated it because when a long section had been published in Penthouse magazine, he had thanked me warmly for printing faithfully what he had said.

I met Ali again in 1977, when, as a go-between, I accompanied Andy Warhol to Fighter’s Heaven. Warhol had been commissioned to paint his portrait. In the three years since Zaire, Ali had defended his heavyweight crown an unheard of nine times. One of these fights included the 1975 ‘Thrilla in Manila’, his third encounter with Joe Frazier. Ali won, but took intense punishment, making him feel ‘closer to death than I have ever been’. And it appears that it was this fight which began the slide into the damaged state Ali must endure for the rest of his life.

Ali’s handlers kept him boxing far too long, and his deterioration was already obvious long before those last two horrific contests with Holmes and Berbick in the early 1980s. The Warhol visit was a pastiche of my earlier encounters. Ali read a poem and delivered a lecture before we could make our escape. The poem had little meaning and the lecture was alarming. After completing his photographic session, before our car cleared the periphery of the camp, Warhol turned to me and asked insistently, ‘But is he intelligent? Is he intelligent?!’

Ali’s handlers kept him boxing far too long, and his deterioration was already obvious long before those last two horrific contests with Holmes and Berbick.

When I knew him in 1973-74, Muhammad Ali was at the top of his game. He sparkled with energy, intelligence and a surreal sense of humour. You can see this dignified, beautiful and charismatic hero in Leon Gast’s Oscar-winning documentary When We Were Kings, much of which was shot during the time this book was being recorded. And you can hear Ali’s captivating and distinctive voice. In one scene he cracks at the camera, ‘Only last week I murdered a rock, injured a stone, hospitalised a brick. I’m so mean I make medicine sick.’ This prompted the New Yorker’s film critic, Anthony Lane, to write, ‘So now we know. Among his many other accomplishments, Muhammad Ali invented rap.’ Writing about the film in the New York Times, Will Sower concluded, ‘In 1974 Mr Ali was one of the world’s most brilliant talkers, especially on the issue of black identity.’

Muhammad in 1973 at Fighter’s Heaven with Victor Bockris.

After 1981, when Ali literally shuffled out of the ring, twice beaten by former sparring partners, he tailspinned into a painful freefall from fame. One day at Andy Warhol’s New York Factory I met the soccer player, Pele. He told me that Ali was having a terrible time adjusting to the loss of the limelight; more seriously he was developing physical ailments which made it hard for him to speak clearly. The chances of becoming ‘the next Billy Graham’ disappeared as suddenly as the big paydays. The sportscasters and boxing writers who had done so well out of Ali when he was making it, knew the truth and faded away. Not only was Ali in and out of hospitals, but much of his money simply vanished. For his final fight, he received less than 10% of the purse.

As far as the sports industry was concerned, the less said about Ali in the eighties the better. Never mind that he had singlehandedly rejuvenated a dying sport, making many millions of dollars for the promoters. He was of no use to them anymore. As far as they were concerned, the sooner he died the sooner they would be safe from any allegations of financial misconduct.

Surprisingly, but perhaps fittingly, it was rock stars who began the rejuvenation of his career, which now has him travelling around the world on a mission for peace and goodwill. Maybe it was because in the eighties the rock community woke up to what Ali had signalled ten years earlier. Part of Ali’s genius in the seventies had been his worldwide, as opposed to national, viewpoint combined with his ability to maximize his energy from the adulation he received. When he was the most famous man in the world, Ali took his fights beyond sports onto the world stage. Speaking into Gast’s camera in Zaire he said he was fighting for Africa, for poor people, ‘for the little brothers sleeping on floors who got nothing to eat … I want to win for the wine-heads, dope addicts, prostitutes, people who got nothing, who don’t know their own history. I can help these people by winning.’

Patti Smith had always celebrated Ali, saying he was the poet she would most like to give a reading with, and treating her concerts like his fights. In the mid-eighties, Madonna often mentioned Ali as an inspiration. New York’s radio king Howard Stern and his sidekick Robin Quivers were also big Ali fans. In the nineties ex-vocalist of Jane’s Addiction and Porno for Pyros, now creator of Lolapalooza, Perry Farrel, said of Ali: ‘The man burned himself up. He made everything look so easy. Something that’s so difficult, taking shots to the face.’

These accounts were written twenty and twenty-three years ago. Reading them now, particularly in light of the renewed interest in Ali with the success of When We Were Kings, and David Miller’s The Tao of Muhammad Ali, gives a unique view of Ali the rapper-writer who could have been. In a third work, Thomas Hauser’s Muhammad Ali in Perspective, there is a photograph taken in 1994 by Ali’s friend and personal photographer, Howard Bingham. It shows Ali and his fourth and most wonderful wife, Lonnie, reading an extremely rare, mint condition copy of my original book. Ali holds it open in one hand with a serene expression on his face while Lonnie, kneeling on the floor to his left, beams up at him. The caption by the black senator Julian Bond reads: ‘Ali doesn’t say as much now as he did before, but he doesn’t have to. He said it all, and said it when almost no one else would.’