PYKE’S REACTION TO the birth of his son David in the summer of 1921 was to book himself an appointment to see a psychoanalyst. Although Dr James Glover became ‘so charmed and so overwhelmed that the analysis fell apart’, Pyke came away with what he wanted. He had gone to Glover for a Freudian insight into a problem that had been troubling him for years, namely, how to give your child a truly enlightened upbringing. Many parents may ask themselves a similar question as they face parenthood for the first time. Few will go as far as Pyke in their pursuit of an answer. It was not that he felt the responsibility of being a parent more than anyone else, rather that he was starting from scratch. As he adjusted to his new life as a father, to the responsibility, the wonder and the occasional sleepless nights, his overriding desire was that his son’s childhood should have nothing in common with his own.

Although he wrote so much during his adult life – to a degree that suggests a compulsion, graphomania – among the millions of words that Pyke committed to paper almost none refer to his upbringing or to his mother. His younger brother Richard compensated for this omission with his first book, The Lives and Deaths of Roland Greer, published in 1928, a roman à clef that focused to the exclusion of all else (including a plot) on the relationship between the four Pyke siblings as children and their mother Mary, barely disguised in the novel as ‘Myra’.

Written in the wake of Mary’s death, while Richard underwent psychoanalysis, it is a stark and often unforgiving portrait of a woman unable to reconcile herself to widowhood. ‘What had been even in favourable circumstances a hasty temper and a shrew’s tongue were transformed by grief, a sense of isolation, and a hatred for all women who were not bereaved, into savage misogyny and a lashing speech that knew nothing of conventions. Half of her was dead, and four ghosts stayed to mock her. As ghosts they haunted her; as at ghosts she lunged at them; like ghosts they left her no spiritual peace.’ In time she grew to love her children, but it was a bullying, paranoid kind of love, that of a dictator towards the masses. ‘Myra was consumed by the feeling that she must fight. It was only thus that her love found an outlet. And fight she did – relatives and servants, strangers and tradesmen; brothers, sisters, mother, children.’ Richard described her ‘hurricane shakings’ and the memory of her ‘fist flourished villainously under his nose, her teeth clenched, her eyes flashing crazy passion, and her face dark red with murder’. His elder brother bore the brunt of this. For Richard the most explosive relationship in that household, the one that seemed to embody its immanent tension, was between Mary and Geoffrey – or Myra and Daniel.

In the book, Daniel is ‘irresistibly impelled by his mother’s widow-hood and his cruelly exploited ambition to fill a father’s place, and to assume responsibilities from which he should have been exempt for many years’. As well as being told, from the age of five, that he was the man of the house, Daniel became Myra’s ‘only formidable opponent, if not her equal’. In one exchange, aged fourteen, Daniel / Geoffrey physically restrains his mother ‘with an expression of utter horror, such as he might have worn if forcing himself to touch a mutilated corpse’. Keeping hold of her, ‘he pushed his elbows outwards and forced them up, thus twisting her wrists round and holding them down’. On wriggling free Myra began to beat him ‘on the side of his head as hard as she could’. Richard later described to a friend how his ‘mother chased them round the dining-room table with a carving knife, and once held Richard out of a third-floor window to frighten him into good behaviour’.

The effect of all this on the four siblings was profound. As a teenager, Pyke maintained that he would never have children for nobody should endure what he had gone through. From an early age the Pykes began to distance themselves from their mother and took to ‘playing at pork butchers and drawing crosses’ in the face of her growing religious conservatism. The more she urged her sons to provide her with Jewish daughters-in-law the stronger their determination to do otherwise. Mary’s elder daughter converted to Christianity, broke all ties with her mother and left home in her early twenties; both of her sons became committed atheists; one refused to talk to her for the last years of her life.

For Richard, this troubled and at times violent upbringing also had the effect of oversensitising all four children. ‘Not only could their emotions be roused far more easily, but they were roused to a far higher pitch, and far oftener, than should have been.’ As well as echoing Mary’s Manichean mood swings the children became familiar from an early age with inconsistency and contradiction. If, as F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote, ‘the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function’, then the Pyke children were precocious.

Of course it was hard for Mary to raise four children in the more straitened circumstances which followed Lionel’s death. Her neuralgia came and went and she was tragically unable to resolve herself to the death of her beloved husband. Perhaps it is unfair to highlight her violent outbursts and the way her children turned against her. But she made mistakes, and for Pyke one of the most egregious was her choice of where, aged thirteen, he should go to school.

By then, Pyke’s atheism and lack of discipline were causing his mother real concern. After five happy years boarding at St Edmund’s, Hindhead, a preparatory school in Sussex, Pyke was not sent to a Jewish day-school in London, where so many of his cousins went. Instead his mother packed him off to Wellington College, the ‘military Lycée’ in Berkshire which embodied the sporty, strict, empire-building ethos of a nineteenth-century public school, and where, at Mary’s insistence, Pyke was to be treated as an observant Jew. He was forbidden from attending lessons or playing sports on the Jewish Sabbath, he had to wear slightly different clothes from the other boys and kosher food was prepared for him at every meal. All this in a school where there had never before been a practising Jew.

He later recalled the sensation of ‘running as fast as your panting breathing will allow you, with a rabble of respectable people thundering and shouting after you. You have only got to see a real man-hunt once in your life, for all your sympathy to go to the hunted.’ This strange spectacle, he added, ‘can always be seen at any really good public school’.

Like sharks scenting blood, packs of teenage boys will pick up on the slightest difference in their ranks and even without his Jewishness paraded like this, the young Geoffrey Pyke was the odd one out at Wellington. He was taller than most and brighter. He was no good at games. None of his family had been in the military. His father was dead. He loved to read. He did not live in the country and had never shot an animal. The bullying that followed was relentless and at times systematic. As well as opportunistic attacks – his brother referred to ‘malicious devils’ brandishing ‘wetted towels’ – there were moments when whole sections of the school chased him along the corridors yelling ‘Jew Hunt!’ or just ‘Pyke Hunt!’

After two miserable years, Mary took him out, and until the age of eighteen Pyke was tutored at home before going up to Cambridge in 1912.

Five years later he was asked to give a talk at Wellington about his escape from Ruhleben. Having run through the first set of lantern slides he described his arrest and the moment when he was told that he would be shot in the morning. The young Wellingtonians were rapt. ‘Yet when things were at their worst in Germany,’ he told them, ‘even when I was quite certain I’d be taken out and shot as a spy, I was never quite so unhappy, never so completely miserable as I’d been when I was a boy here at Wellington.’

It was not just the bullying and the casual anti-Semitism which had worn him down, so much as the unimaginative teaching and relentless emphasis on discipline for discipline’s sake. George Orwell, briefly at Wellington soon after Pyke, described the school as ‘beastly’. The author, politician and publisher Harold Nicolson, another contemporary, described being ‘terribly and increasingly bored’ there. ‘One ceased so completely to be an individual, to have nay but a corporate identity.’ Nicolson later ‘blamed the Wellington system for retarding him mentally and socially’. Naturally Pyke did not want his son to endure anything similar. So where to send him instead?

Perhaps this was the wrong question. The problem might not be with Wellington per se but the English educational system as a whole.

The early 1920s was later described by Evelyn Waugh as ‘the most dismal period in history for an English schoolboy’. The expression ‘spare the rod and spoil the child’ was not yet a historical curiosity and in schools up and down the country the ghost of Dr Arnold stalked the battlements. Arnold was the Rugby schoolmaster who had done more than any other to change the character of so many English schools – until ‘an English public schoolboy who wears the wrong clothes and takes no interest in football, is a contradiction in terms’, as Lytton Strachey had pointed out several years earlier. ‘Yet it was not so before Dr Arnold; will it always be so after him?’ The assumption for most British parents was that yes, it would. The character of these institutions appeared to be entrenched, the people running them had little incentive to change and it was hard to see why or how things would evolve.

As he had done in the face of those who believed that no Englishman could slip into Germany undetected, or that escape from Ruhleben was impossible, Pyke challenged these verities. In the months after David’s birth he reached a pivotal realisation. To give his son the education he wanted for him he must set up his own school. Of course he had no experience of teaching and only an amateur interest in educational theory. Even if he was able to get down on paper a convincing outline of a radical new establishment, it was hard to see how he could persuade any parents to offer their children for this scholastic experiment. This was a risk he would have to take.

Over the following months he developed the blueprint for a new kind of school, one that would go further than existing progressive models such as Bedales, Abbottsholme, The King Alfred School or St Christopher’s in Letchworth Garden City, and take in children at a younger age. It drew on the painful lessons he had learnt growing up and combined them with ideas filleted from Rousseau, contemporary philosophy, psychology and Freudian psychoanalysis. Underpinning it all was his ardent belief that each of us arrives in the world as a scientist in the making, that as children we are naturally inquisitive and will conduct experiments in order to understand the world around us. This new school would be revolutionary and scientific. It would also be hugely expensive to set up. If David Pyke was to have the ultra-modern upbringing his parents wanted then they would have to raise a lot of money, and fast. In many ways this was an even greater challenge.

Pyke’s job at the time was poorly paid and precarious. He had been employed by the Cambridge Magazine since 1916, and while he had always seen this as a cause as much as a livelihood, identifying with its internationalist anti-war perspective, the demand for such publications had evaporated since the Treaty of Versailles. In 1922, Pyke was asked to dispose of its most valuable asset, a weekly survey of the foreign press. He sold it to the Manchester Guardian, and later that year the magazine folded. Very soon after, another pillar in his life began to totter: Mary Pyke told her children that she was dying of cancer.

Having refused to see her during the previous five years, Pyke now visited her in the nursing home – in body if not in spirit. He had cut her out of his sentimental attachments with such finality that now it was as if he was seeing her for the first time. Mary did not seem to notice. Indeed, as she lay there surrounded by her four uncomplaining children, her sense of family, as Victorian as it was Jewish, was at last satisfied. Over the days that followed her face greyed, the cancer spread and the daily dosage of drugs was increased. Her stream of complaints about the nursing staff petered out, and on 18 August 1922, aged 57, she died.

Her corpse was taken to Willesden Green Cemetery where just one exception was made to the orthodox Jewish ritual. Following her instructions, Mary Pyke was buried wearing her wedding ring. Pyke found the funeral shocking and lonely, and would later urge his son to stay away from his, describing it as ‘a silly business’.

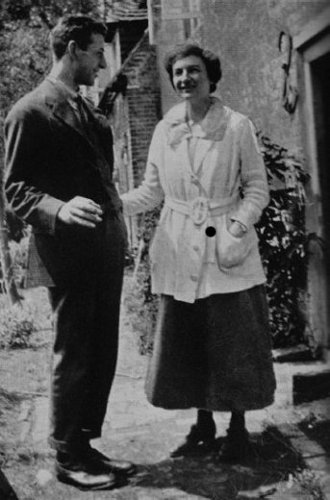

The death of his mother and the end of the Cambridge Magazine produced in Pyke an overwhelming urge to get away, and the next month his passport application was finally approved. He had been removed from MI5’s Blacklist. Yet this was not in response to fresh intelligence which exonerated him from suspicion – indeed, five months later MI5 would refuse a request from the Passport Office to remove him from their ‘Special File’ – but he was free to leave the country and did so at once, setting off with Margaret for the Swiss Alps.

Geographically, emotionally, sexually, they had never felt so free. Though married and in love, neither claimed a proprietorial hold on the other. Even if this went against the gospel according to Shaw, who wrote that ‘a real marriage of sentiment [. . .] will break very soon under the strain of polygamy or polyandry’, the Pykes professed a looser sexual morality, not in a bohemian spirit of laissez-faire but as part of what they saw as a more scientific approach to life.

The word ‘scientific’ had a particular resonance by then. Once confined to machines and laboratories, there was a fashionable new sense that a scientific perspective could be applied to everything. Science could do away with all traditional assumptions – indeed, the word had come to stand for a youthful rejection of what one’s parents had taken for granted. Shaw envisaged a society dominated by scientifically minded ‘engineer-inventors’; H.G. Wells referred to ‘scientific samurais’, the men and women of tomorrow who would rise to the top by dint of their ruthless intellectual technique, slicing through a thicket of outdated prejudices. While there was nothing new about this urge to cast off Victorian certainties – journalists, novelists and playwrights had been doing this since the turn of the century – by the early 1920s this project had a pronounced urgency. The blind slaughter of the trenches seemed to be evidence of what happened when society was run according to traditional precepts. The Soviet Union, dazzling in its potential, suggested that it was possible to reinvent an ancient nation along more scientific lines. This was not to say that a scientific attitude must always be left-wing, only that it implied starting from scratch. For the likes of Geoffrey and Margaret Pyke, science allowed for a modern perspective on everything from sexual morality to warfare, the education of children and, of course, the business of making a lot of money quickly.

In late 1922, having sublet his Bloomsbury flat at 41 Gordon Square to Maynard Keynes, the renowned economist who had recently made and lost a fortune in currency trades, Pyke began a meticulous and what he called ‘highly scientific’ study of the financial markets. This was where he hoped to make his money. While it is tempting to imagine him discussing some of his ideas with his new tenant, Keynes, the economic heavyweight of the twentieth century, there is no evidence of this. Nor did he consult any of his cousins who worked in the City, preferring instead to come at this subject as an outsider, a scientific samurai in search of an original insight.

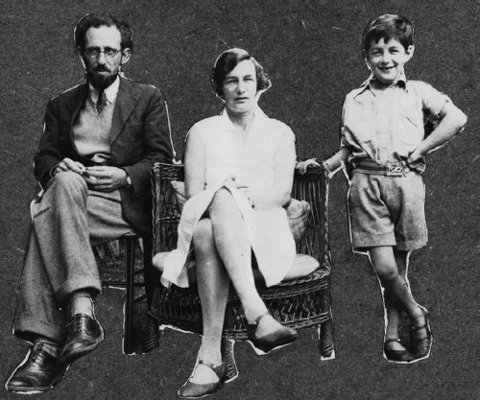

The Pykes had moved from Gordon Square to Cambridge where they got to know one of Keynes’s protégés, a brilliant yet hormonally charged undergraduate named Frank Ramsey. Earlier that year, aged nineteen and already a member of the Cambridge Apostles, perhaps the best known of all university secret societies, Ramsey had produced the first English translation of the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, a feat made even more remarkable by the fact that he was then studying mathematics (and would later be awarded a stunning First). Ramsey was owlish and precocious, a prodigy for whom the solution of philosophical and mathematical problems came easily. Social relations were more confusing, and none more so than those which involved women.

During the first few months of 1923 Ramsey saw the Pykes daily and at the same time became a close friend of Pyke’s brother Richard, then reading Economics at King’s College. Indeed, Ramsey got to know Geoffrey and Margaret so well that they asked him to become David’s godfather – meant in a strictly non-religious sense for the Pykes and Ramsey were determined atheists. Whether or not Ramsey accepted, he was keen to maintain his close relationship with the Pyke family. By that stage of his life Frank Ramsey had become infatuated with Margaret Pyke.

Unaware of his feelings, the Pykes invited him to come away with them over Easter to Lake Orta, in the foothills of the Italian Alps. Noting with approval that Pyke claimed no ‘proprietary rights’ over his wife, so that if she ‘announced she was going off with someone else he would be pleased because she was going to be happy’, Ramsey accepted.

Pyke’s study of the markets was acquiring greater focus. He had homed in on commodities futures and in particular the metals market, where he studied the relationship between the prices of tin, copper and lead as if they were the movements of the Ruhleben sentries. He wanted to know everything about them. He drew graphs charting their fluctuations and discussed these with friends from the London School of Economics. Yet by the time he set off for Italy no patterns had emerged and he appeared to be no closer to generating the fortune he needed for his pioneering school.

In the romantic setting of Lake Orta, Ramsey’s feelings for Margaret became overwhelming until at last he decided to act. One hot afternoon the two of them went out together on the lake before settling down to read. Unable to concentrate on his book, Ramsey gazed over at Margaret, thinking to himself how ‘superlatively beautiful’ she looked in her horn glasses. At last he broke the silence.

‘Margaret, will you fuck with me?’ he asked.

Either she did not hear or, more likely, could not believe what he had said. Ramsey repeated the question.

‘Do you want me to say yes or no?’

‘Yes,’ he exclaimed, ‘or I wouldn’t ask you!’

‘Do you think once would make any difference?’ she asked.

‘I don’t know, perhaps that is the question[.] I haven’t thought it out,’ he admitted. ‘I just want to frightfully.’

Margaret was both open-minded and inoffensive. She said she needed time to think it over. Ramsey’s response was to tell her that his psychoanalyst had warned him that if he did sleep with her he would probably be unable to perform. Relieved at having got this off his chest, Ramsey then went for a walk by the lake feeling ‘awfully pleased at having some chance’.

On his return Margaret’s response was a polite no. But this was not a total rejection. Back in Cambridge he kissed her for the first time and ‘then came a wonderful afternoon when she let me touch her breasts, partly (I discovered) because she thought it was genuine curiosity’. Sadly we do not have Margaret’s version of events.

Just before setting off for Austria that summer to find Ludwig Wittgenstein and talk him out of philosophical retirement – a trip that would change the course of twentieth-century philosophy – Frank Ramsey went to stay with the Pykes. He was dismayed to find that Margaret ignored him entirely, until ‘Geoff told me as it were fortuitously that he probably only had two years to live and I understood M’s behaviour and felt full of love for G and pity.’

There are no other references to Pyke’s life-threatening illness except for a note he wrote around this time explaining how the news of his death should be relayed to David. ‘The adaptation should be gradual and unaccompanied by any shock.’ His son ‘will tend to feel it tragic just so much [. . .] as the matter is treated tragically by those [with] whom he comes in contact’.

This tells us something about how the news of his own father’s death was conveyed. Even at the end of his life, those close to Pyke suggested that he had never fully recovered from the shock of losing his father and it seems that the way this news was handled played a major part in this. As for his illness, all we know is that by the time Ramsey returned from Austria several months later Pyke had recovered. Yet Ramsey’s infatuation with Margaret had, if anything, become worse.

The young philosopher decided to clear things up with a letter. ‘I wrote and asked her if (1) I might caress her breasts (2) see her private parts (3) if she would masturbate me.’ Margaret was not won over by this bullet-point approach – indeed, she found Ramsey’s letter deeply upsetting – and for now he was forced to keep his distance.

Meanwhile Pyke put the finishing touches to his financial model. After months of painstaking research, he had developed a ‘tentative hypothesis’ about the relationship between the prices of copper and tin, two staples of the London Metal Exchange. He had found an inverse correlation between the two prices. Put simply, if the price of one went up, the other tended to go down. Within any futures market a mathematical relationship of this simplicity was the philosopher’s stone. If accurate, he stood to earn a fortune.

Using money he had been left by a relative and some of the proceeds from his book, in the second half of 1923 Geoffrey Pyke took the greatest financial gamble of his life. As a newcomer to the metals market he gambled his savings on the basis of a home-made financial model.

During March 1924 three versions of an unusual advertisement appeared in successive issues of the New Statesman and Nation. ‘WANTED—’, each one began, ‘an Educated Young Woman with honours degree – preferably first class – or equivalent, to conduct the education of a small group of children aged 2½–7, as a piece of scientific work and research.’ The successful applicant, it went on, would receive a ‘liberal salary’.

Pyke’s financial model had worked. During the first six months of trading he was said to have earned £20,000 (more than £600,000 in today’s money); Ramsey noted that Pyke ‘now made £500 for every £1 the price rose, and so expected to make much more’. To generate these spectacular returns he had acquired debt, some of which was unsecured by real assets, but this was in the nature of this kind of speculation and in itself was not worrying. Far more important, just then, was the business of finding the right head teacher for David’s new school.

The notices in the ‘Staggers and Naggers’ worked in the sense that they caused a stir. By 1924 the supply of teachers far outstripped the demand, so to have a teaching position advertised in this way was remarkable. Several readers of Nature, where a similar version of the notice had appeared, assumed that it was the work of white-slave traders planning to sell the unwitting applicants into bondage. Others were intrigued by the lines about preference being ‘given to those who do not hold any form of religious belief’, and that work would be preceded by six to eight months of paid training. Training in what, exactly?

Nathan Isaacs, a precocious and self-effacing German Jew who had fought for the British during the war and been gassed at Passchendaele, found his curiosity piqued by a different line. The advertisement had called for a woman who had ‘hitherto considered herself too good for teaching’. Isaacs thought immediately of his wife, Susie.

She took one look and dismissed it as the work of a crank. Yet in the weeks that followed she spoke by chance to Dr James Glover, the psychoanalyst who had tried to analyse Pyke and was now on the school’s board. He suggested that at the very least Susie should meet with Pyke. She looked at the advertisement again.

Susie Isaacs, then thirty-nine, was a wiry Lancastrian with thick blonde hair and a pale complexion who had a habit of jutting out her chin when animated. She was intelligent, bookish and driven. She had a rebellious streak. After her mother had died when she was six, she was raised by her father, an imposing Methodist preacher, who took her out of school when he heard that she had become a Fabian and an atheist. Following his death in 1909, independent at last, she went to the University of Manchester and was awarded a First in Philosophy before taking her Master’s degree at Newnham College, Cambridge. The following year she married the botanist William Brierley, but the marriage soon broke down, whereupon she went to London to develop her interest in psychoanalysis and write what would become a bestselling introduction to psychology. In 1921 she was psychoanalysed in Vienna by Otto Rank, a follower of Freud (whom she had hoped to be analysed by), before giving a lecture later that year that would change her life.

It had taken place at the Workers’ Educational Association, in London, and in the audience had been Nathan Isaacs, ten years her junior. He pursued her, and soon they fell in love. Though the teacher-student dynamic never really disappeared, they became a tight fit intellectually, with Nathan more accommodating and perhaps lighter on his feet. Even if it meant that her teaching position had to end, Susie agreed to marriage.

Several years later they both went to meet Pyke for the first time. The three of them clicked almost immediately. The subject of that first conversation ranged from the boundaries of self-understanding and repressed sexual urges to the impact of childhood on one’s adult psyche. Each one was fluent in the language of psychoanalysis, and over the following months Pyke ‘lived almost as one of us’, wrote Nathan, who went on to call him ‘undoubtedly an educational genius!’ Susie’s feelings were more complicated.

As ever, Pyke did not imagine that he had all the answers. He wanted Susie and Nathan to help fill in the gaps and provide fresh angles on the existing problems, and out of these passionate, lively conversations during the summer of 1924 came Susie’s appointment as Principal of the new school. Several months later, on 7 October, the three-year-old David Pyke was joined in a gabled former oast house in Cambridge by nine boys between the ages of two and four. Girls would soon follow. It was the first day of term at Malting House School, one of the boldest experiments in pre-school education anywhere in the world.

Imagine yourself to be one of those children. What would you have noticed as you began to explore the new school for the first time? For one thing, a lack of classrooms. Instead you would have ventured into a vast play area dominated by a piano (which you could play whenever you liked) and a space beyond filled with nothing but cushions and mattresses where you could take a nap. You would have also found that all the shelves and cupboards had been lowered to be at your height, something you had probably never seen before. Otherwise you might have been amazed by the piles of books, bulbs, beads, shells, counters and wooden blocks for you to investigate whenever you liked, as well as the mechanical lathe, two-handled saw, Bunsen burners, gramophone player and tools for dissecting animals – all of which you could use with the minimum of supervision. As you would soon find out, from an improbably early age children at the Malting House were to become familiar with both the principles and reality of scientific experimentation.

The area you would have been most intrigued by – the one which children at Malting House spent more time in than any other – was the garden. Following Rousseau’s idea that the most beneficial child development takes place outside, in nature, which was why early Malting House literature referred to the children as ‘plants’, the garden had been transformed over the summer into an edenic playground. You could climb the trees and look after the hens, rabbits, mice, salamanders, silkworms and snakes. You were given a garden plot to look after and could make bonfires to see how different matter burned. You could also clamber over a state-of-the-art climbing frame, which had been shipped in from abroad, or jump around on the lopsided see-saw with adjustable weights (to illustrate mechanical balance). If all this failed to capture your imagination you could always play in the giant sandpit which was sometimes flooded and turned into a pond.

If you were a particularly observant child, you might have noticed that in each room, at a level which you could not reach, there were books which the adults liked to write in. The Malting House was a scientific experiment as much as a school, and as such everything was to be recorded. Which child played with what, when, how, and the questions they asked, all of this was jotted down during the day and typed up later on. Too often in the past, felt Pyke, judgements about child development had been made first and supporting evidence found later. He wanted to spin this round. His school would be an environment in which almost all adult influences were removed, leaving children to be observed in their ‘natural’ state. This decision to record everything would be significant, and explains why Malting House went on to have such a lasting impact on British education. Yet what really distinguished it from other pre-schools and explains why it attracted the brightest toddlers in Cambridge, including the grandson of the Nobel Prize-winning chemist Sir Ernest Rutherford and the children of the philosopher G. E. Moore, had to do with what happened when a child asked a question.

Early on in the school’s history one of the children asked the name of the funny-looking box into which adults sometimes talked. He was not told that it was a telephone. Instead it was suggested that together they call it ‘a telephone’. Great emphasis was placed on allowing the children to feel as though they were discovering the world for themselves, even if they were often being steered towards the correct answers. Having worked out what to call it one of the children asked what it was for. The staff at Malting House never responded to a question like this with a straightforward statement of fact, and instead had been drilled to say, ‘What do you think?’ or, their favourite, ‘Let’s find out!’ So rather than being told what this so-called ‘telephone’ was for, the children were asked to think of all the practical uses to which it could be put.

Here was another thread in the school’s philosophy: discovery must be allied to utility. This was probably inspired by H. E. Armstrong’s theory of heuristics, in which effective learning was associated with discovery as well as action. Rather than be told that it was important to learn, say, how to write, because that was what you were meant to do, the children were encouraged to see that writing would allow them to send letters to their friends or let the cook know what they wanted on the lunch menu. (Once they had learnt how to write they ordered almost nothing but chicken.) Later they would be encouraged to budget these weekly menus, do the washing-up, make their own clothes or repaint tables and chairs. As well as helping them to discover the world for themselves, there was a desire to give the children as much autonomy as possible.

On the day that one of the children asked about the telephone, it was agreed that this strange box could be used to invite their friends from outside the school over for tea. Now that they had an incentive to master it, they set about calling these friends and learning how to keep records of their numbers. Without any timetable to get in the way, they spent the rest of the day tackling further questions about the telephone, at one point following the wire which came out of it round the school and out to the street. Later they went on an outing to the local telephone exchange to meet the operator and solve the riddle of why there was a female voice stuck in the receiver.

Wherever possible, the direction and speed of learning was generated by the children. Indeed there were no ‘teachers’ at Malting House, just ‘co-investigators’. It was a learning environment without timetables or formal instruction, one in which curiosity and fantasy were rewarded. The contrast to most 1920s kindergartens was acute. At Malting House each child was seen as ‘a distinguished foreign visitor who knows little or nothing of our language or customs’, as Pyke put it. ‘If we invited a distinguished stranger to tea and he spilled his cup on the best tablecloth or consumed more than his share of cake, we should not upbraid him and send him out of the room,’ he explained. ‘We should hasten to reassure him that all was well.’ In other words, there were to be no punishments, a reminder of the influence of Freud on the school.

Sigmund Freud’s theory of psychoanalysis was seen by those in Bloomsbury and beyond as the defining scientific discovery of the age. At its heart was the idea that we bury in our unconscious the memory of shocking or traumatic experiences, only for these memories to resurface later as nervous conditions. The effect of Freud’s theory could already be seen in contemporary literature, philosophy and the treatment of post-traumatic stress, yet by 1920 nobody had thought to apply Freudian psychoanalysis to education. Around the time of David Pyke’s birth in 1921 this began to change. The Institute of Psychoneurology’s ‘Children’s Home’ had opened in Moscow – Stalin’s son Vasily was one of the first pupils – and later that year A. S. Neill’s Summerhill school opened in Germany. Like the innovators behind both of these institutions, Pyke wanted the children at his school to come away without traumatic memories to suppress, nor any association between punishment and either sexuality or the natural function of their bodies. Yet by 1924 neither Summerhill nor the Moscow institute had written up the results of their endeavours. By recording everything at Malting House, Pyke had gone further than either school. His was the first valid experiment into the idea of reorganising education in the light of Freud.

The lack of structure and discipline at Malting House was not without problems. Though the children there were brighter than most – the average IQ in 1926 was 131 – a surprising number showed signs of psychological imbalance. Susie Isaacs later described their initial intake as ‘the ten most difficult children in Cambridge’. Her account of 31 October 1924, is typical: ‘B., as on one or two previous occasions, hit me in anger. I tried passive resistance, but he went further, and hit me several times, hard, stinging blows with the open palm, and was gleeful when he thought he had really hurt me and “made me cry”.’ She concluded with studied detachment: ‘The method of remaining passive did not appear the answer.’

‘I must say I can’t make out the point of it,’ wrote James Strachey, one of Freud’s first translators, who had married Pyke’s friend Alix Sargant Florence and had a niece and nephew at the school. ‘All that appears to happen is that they’re “allowed to do whatever they like”. But as what they like doing is killing one another, Mrs Isaacs is obliged from time to time to intervene in a sweetly reasonable voice: “Timmy, please do not insert that stick in Stanley’s eye.” There’s one particular boy (age 5) who domineers, and bullies the whole set. His chief enjoyment is spitting. He spat one morning onto Mrs Isaacs’s face. So she said: “I shall not play with you, Philip,” – for Philip is typically his name [Philip was also the name of Strachey’s brother-in-law] – “until you have wiped my face.” As Philip didn’t want Mrs Isaacs to play with him, that lady was obliged to go about the whole morning with the crachat upon her.’ Though Strachey never visited the school, and loathed Susie Isaacs for her sometimes serious manner, his account was not too wide of the mark.

As well as spitting a great deal, the children would often gang up on one of their classmates and shout ‘funny face’ at them before locking him or her in the henhouse or shutting them out of the school altogether. The victim might change from day to day, but the urge to do this was constant. As well as upsetting the child who had been singled out, this was becoming expensive. The children who were locked out tended to break a window on their way back in. Others had developed a taste for smashing plates when things did not go their way. The school’s Freudian approach ensured that adults could not censure a child if they did this, or indeed if they took too much interest in another’s turds or genitals. The Malting House was rapidly becoming known around Cambridge as a ‘pre-genital brothel’. Pyke and Susie had hoped that if this behaviour was simply ignored it would lose its appeal. They were wrong.

Towards the end of the first term Pyke’s educational experiment had reached a critical point. Over the past seven weeks valuable insights had been gained into what happens when you give a pack of two-to-four-year-olds almost total freedom. The number of stories and imaginative games they invented shot up. The children had also begun to show the kind of scientific curiosity that Pyke and Susie had predicted. But by now they were in open rebellion against the adults. It was becoming the law of the jungle and for the first time in the short history of Malting House it seemed as though this bold venture had run its course.

Pyke saw things differently. After all, it was no more than a case of identifying and reformulating the problems they faced: solutions were bound to follow.

Pyke began with the question of how to prevent the children from ganging up on each other without explicitly forbidding it, for this would do little to curb the original desire. Rather than ban it, he turned it into more of a game. How? By volunteering himself to be ‘funny face’.

Over the days that followed Pyke spent many hours locked in the Malting House henhouse as one of the children’s prisoners – a strange echo of his solitary confinement in Berlin.

It worked. The game lost its sting and when he suggested that those children who had shut him up should take a turn in the henhouse they rapidly lost interest.

There was also the problem of ‘spitting or excremental talk’. Again it contradicted the school’s principles to punish the children for this, so instead he instructed the staff to withdraw their help as soon as it began, and in some cases they ‘explicitly requested that there be no more such talk, and only one child in the lavatory at a time’. If a game became violent, rather than stand idly by, the adults would immediately start a different game. Pyke also introduced a handful of guidelines: children must be punctual; material had to be put away after use; nobody was to endanger themselves or others.

These sound like tiny adjustments, none of them commensurate with the crisis at Malting House, but together they worked. Susie noted with approval that ‘the individual aggressiveness of the children has grown much less’ and, several weeks later, that there was a new ‘pleasure in co-operative occupation’.

Something else changed at Malting House towards the end of that first term. Whether or not any of the children noticed, there was a different chemistry between two of the adults. Just as the school was a testing ground for experimental attitudes and ideas, these two individuals had long believed that marriage was not an expression of exclusive physical ownership and that ‘the sexual act’, to quote one of their Cambridge friends, was really ‘like a kiss’ and ‘merely a demonstration of affection, more violent, more pleasurable but essentially of the same nature’. But neither had yet put this attitude to the test.

That summer, in Vienna, Frank Ramsey had lost his virginity to ‘a charming and good-natured prostitute’ and had been psychoanalysed by one of Freud’s disciples, Theodor Reik, in the hope of ending his obsession with Margaret Pyke. As Lytton Strachey gossiped to his brother James, Ramsey had left Vienna thinking he was ‘cured of such wishes. On returning and meeting her, however, he was more bowled over than ever, but asked her to go to bed with him – which she declined.’

Ramsey’s infatuation was now common knowledge around King’s College. Pyke even joked about it with Ramsey’s mother – which Ramsey resented terribly. Maynard Keynes warned Ramsey around this time that the rumours about him and Margaret Pyke could damage his chances of being offered a fellowship at King’s, advice which might have helped drive him into the arms of the undergraduate Lettice Baker.

Rather amazingly, Baker was then sleeping with Pyke’s brother Richard, still one of Ramsey’s close friends. It seems that this Cambridge prodigy made a habit of falling for women who were sleeping with one of the Pyke brothers. Margaret was at last off the hook, but this gave way to a new complication in her life: her husband and Susie Isaacs had begun to have an affair.

Pyke had become overwhelmed by the fantasy of having found in Susie the complete modern woman, similar to Margaret but more combative and one who understood the pain of losing a parent at a young age. They were drawn together by the music of their conversation. The psychoanalyst John Rickman described Pyke and Susie in full flight as like ‘watching a fine exhibition of ballroom dancing, the movement of their minds was in such close touch that it seemed as if a single figure moved in the intellectual scene, she skilled in philosophical method followed his sterner logic, he yielded to her more subtle psychological intuition’. The longer this dance went on the closer they became, until their intimacy in conversation felt like an open infidelity. ‘Geoffrey turned more and more to Susie as a confidante,’ Nathan later wrote, ‘as to one who was more important to him than anyone else, as to the woman he had been looking for and hoping for all these years. Susie wasn’t less drawn to him, let us say.’

They slept together for the first time in late 1924, and while Susie admitted later that ‘she didn’t feel any overpowering longing for intercourse, she was quite ready for it’. By March 1925 the Director and the Principal of Malting House were ‘in full and open love with one another’, with Susie describing her ‘very real love’ for Pyke. Rather than wink at this infidelity, Margaret gave it her ‘blessing and active encouragement’. Nathan, however, remained in the dark for now.

Sexually it was a disappointment. Pyke later conceded that ‘he had not been a very satisfactory physical lover’, and if his brother’s novel is anything to go by, we may have some idea why. In The Lives and Deaths of Roland Greer, Richard Pyke described his fictional self being unable to ‘rise to the occasion’ and having ‘secret difficulties’ in ‘sexual matters’. He added that his elder brother ‘understood too well’ these difficulties ‘because they were his own too, though he overleapt them by a tour de force – a method which cannot be imparted’. Either this tour de force could not always be relied upon or he and Susie naturally grew apart: after a year of the affair she ‘decided to go no further’ and by the start of 1926 their relationship was no longer physical.

Even then, as Nathan, the unlikely chronicler of the affair, recalled, ‘the draw they were exercising on one another was more powerful than ever’. To most observers it seemed as though their liaison had ended amicably and that the school would not suffer, but there was a storm on its way. It would test not only the fragile nature of their relationship but the very existence of the school they had made together.

By early 1926 the Malting House experiment was in full bloom. Having overcome those initial difficulties it was now winning international plaudits from leading educationalists of the day such as Jean Piaget, who would soon pay an approving visit, as well as Melanie Klein, the psychoanalyst and expert in child psychology. Klein even performed at Malting House one of the first psychoanalyses of a British child on David Pyke, then aged four. Yet they were at cross purposes throughout. David had recently been given an old bus conductor’s tray and was determined to sell Klein a ticket for his bus. She was only interested in finding out whether he had seen his parents having sex, which he might have done, only not with each other.

As the prestige of Malting House grew, so did Pyke’s stock within Cambridge. The physicist and engineer Lancelot Law Whyte later described him as one of the leading lights of 1920s Cambridge, alongside Sir Ernest Rutherford, Peter Kapitza and E. M. Forster. He was a playful conversationalist, an entertaining bauble on the tree of academic life who ‘looked like an Assyrian king’ and was, if nothing else, a doer in a city full of thinkers. ‘Philosophers have only interpreted the world,’ wrote Marx, ‘the point is to change it.’ Pyke did not just talk over tea on the High Street about the possibility of making a fortune on the stock market – because it looked so easy – or the need to revolutionise education by applying the lessons of Freud. This thirty-three-year-old did these things – and they worked. None of it seemed to be a fluke. His success was the result of his small inheritance, dazzling self-confidence and a capacity for laborious research.

By now his Cambridge social circle had expanded beyond undergraduate friends such as Philip Sargant Florence, then on his way to becoming a renowned economic theorist and whose children were at Malting House, or his editor at the Cambridge Magazine, C. K. Ogden. Newer Cambridge friends included the film-maker Ivor Montagu and the couple at the end of the Malting House garden, Phyllis and Maurice Dobb, he a young economist at Trinity College. There was also crystallographer J. D. ‘Sage’ Bernal and his wife Eileen, who had recently become involved in Pyke’s financial operation, as well as J. B. S. Haldane, the legendary biologist who had joined the Malting House board, and his wife Charlotte, well known for her literary salons.

It is interesting that at least five of these new friends either joined the Communist Party, worked for Soviet intelligence or did both. A decade later there would be nothing remarkable about having so many Cambridge friends who subscribed to dialectical materialism and saw the USSR as a beacon of radiant utopian possibility. But during the mid-1920s it was unusual – in the General Strike of May 1926, in which the Moscow National Bank aided some of the striking miners, almost half of the city’s undergraduates were thought to have been involved in efforts to break the strike.

Although he had a number of Marxist friends there is no evidence that by 1926 Pyke shared their political views. Since his political epiphany in Berlin he had remained close to the Fabianism of Sidney and Beatrice Webb and Shaw, and had corresponded with all three, but he did not give himself the time to take any of this further. If nothing else, he was ‘intensely distracted’ both by the school and the newfound complexity of those financial dealings on which Malting House depended.

In the early days Pyke had been making straightforward directional bets on whether the price of a certain metal would rise or fall, guided by his hypothesis about the relationship between copper and tin. As with comedy, the key to this was timing. Generally he got it right but occasionally he lost money. To reduce the scope for error Pyke had concocted a new trading system. He was now making what traders today will call ‘relative value arbitrage trades’ using ‘advance-dated double options’. Even by modern standards this is an exotic trade. At the time it was pioneering. Rather than bet on whether the prices of copper and tin were going up or down, he now predicted the deviation between the two. As he later explained in court, ‘it no longer made any difference whether prices went up or down as long as they did not separate or separate in one direction.’ Compared with his earlier dealings this was ‘immensely less speculative’. He increased his margins accordingly and used some of the new profits to employ a team of researchers in offices off Chancery Lane. This was all going well until he realised that he would soon be facing an enormous bill for income tax.

Having poured his profits into either the school or increasing his holdings in the metals market, he was unable to pay. He sought the advice of a barrister: D. N. ‘Johnny’ Pritt KC, later described by a Soviet defector as ‘one of the chief recruiting agents for Soviet underground organisations in the UK’. Pritt assured Pyke, in answer to his question, that it was perfectly legal to alter his operation so that he was no longer trading as an individual but through a series of companies. This would turn his taxable income into a capital gain, meaning that there would be less tax to pay. But there was more to this plan. If he set off these gains against losses incurred by buying options on the companies’ shares from the shareholders then he could reduce the money he owed to almost nothing.

Pyke duly set up two companies, Orcus and Siona (a misspelling of ‘ciona’, a stationary sea creature which sits on the bottom of the ocean and feeds off passing plankton), and began to buy options from his shareholders at exorbitant prices. Whether or not Pritt knew that each of the shareholders was an acquaintance of Pyke by one remove, or an employee, is unclear. The new system worked. Pyke no longer faced a crippling tax bill, while his sway in the metals market continued to grow. Had he settled up with just one of his three brokers on Christmas Day 1926, when he was said to hold a quarter of all tin reserves in Britain, he would have walked away with a trading profit of over £20,000. But he saw no reason to do this.

Though he never visited the trading ring of the London Metal Exchange he was by now so well known there that he had a nickname, ‘Candlesticks’, after cabling in a trade from the Swiss town of Kandersteg. Even the editor of Metal Bulletin had heard of ‘Candlesticks’ and was ‘certainly impressed by his market activities’. Less impressed, however, was a group of heavyweight American copper producers.

In October 1926 there was a historic meeting of the world’s most powerful copper magnates. Between them they controlled up to 90 per cent of the global copper supply with mines in Africa, South America and across the United States, yet they did not control the price of copper and, as they resolved at this meeting, that needed to change.

The United States was entering a period of frenzied financial speculation. With the largest bubble in American finance beginning to form, these copper producers wanted to take steps to protect themselves against price shocks, which were usually caused by the activities of lone speculators. Using the Webb-Pomerene Trade Export Act of 1918, originally designed to boost the American war effort by granting immunity to certain export companies from standard anti-trust regulation, they formed a cartel of historic proportions. Copper Exporters Incorporated (CEI) was later described as ‘the most formal cartel in the twentieth century in American industry’. It was powerful and coordinated and had been formed with the sole aim of stabilising the copper price. The best way to do this was by flushing out speculators like ‘Candlesticks’ in London. First the CEI needed greater control of the market, which would take a little time. Having started out with ambitions to do nothing more than pay for his son’s enlightened education, the scale of Pyke’s success had turned him into a target.

Just before this copper cartel came into being, Pyke reached a momentous decision. David was now approaching his sixth birthday and in a year or so would need to go to a new school, unless, that was, Malting House could be adapted to accommodate him and other children of his age. Pyke decided to turn the school into an international institute for educational research which could care for children all the way through to university. It had always been in his nature to take ideas to an extreme, and now he would do the same to his groundbreaking school. So he began to spend.

Pyke appointed Nathan Isaacs as the school’s researcher-at-large on £500 a year, telling him to ‘run away and read and write’ on questions like ‘Why do children ask “why”?’ At enormous expense, he hired stenographers to record every word the children spoke. He also lavished more than £1,000 on advertisements for the school’s first scientific appointee, and arranged for a selection committee made up of Sir Ernest Rutherford, J. B. S. Haldane and Sir Percy Nunn. When the Daily Express heard that a science teacher had been employed by a kindergarten they sent their Crimes Reporter to investigate. This type of prurient interest in the school persuaded Pyke of the need to publicise his work in a sympathetic light.

During the summer of 1927 he commissioned a promotional film from a prestigious production company which specialised in battle scenes and wildlife documentaries. Despite their obvious qualifications for the job, they found the task somewhat challenging. ‘In all our experiences of photographing every kind of wild creature, not excepting cultures of bacilli, the problem of photographing children in their wild state proved the most difficult to tackle,’ grumbled one cameraman. ‘Whereas animals can be more or less localised and controlled by food, and bacilli must remain within the confines of a test-tube or petrie-dish [sic], no such artificial fixity could be obtained with the children.’ Eventually the children lost interest in the cameras, and were recorded dissecting Susie’s recently deceased cat – ‘It fair makes you sick, doesn’t it?’ a cameraman whispered to his producer – as well as starting a bonfire that got out of hand and burnt the school canoe. ‘Even Geoffrey Pyke was a bit upset about that.’ Ten days later they had enough material to cut a half-hour-long film.

‘Remarkably interesting and altogether delightful,’ was the Spectator’s verdict on Let’s Find Out, after initial screenings in Manchester and London, where 500 people came to watch it in the Marble Arch Pavilion. The children appeared to be:

‘having the time of their lives, wading up to their knees trying to fill a sandpit with water, mending a tap with a spanner, oiling the works of a clock, joyously feeding a bonfire, dissecting crabs, climbing on scaffolding, weighing each other on a see-saw, weaving, modelling, making pottery, working lathes – in fact doing all those things which every child delights in doing. At Malting House School children’s dreams come true. The school is equipped with the most extensive apparatus, which will stimulate the natural curiosity possessed by every child. [. . .] There is no discipline. There are no punishments. Children may hit one another so long as they only use their hands, but I believe quarrels are rare and, though it seems almost unbelievable with the unending opportunities which must occur, there has never been an accident of a serious nature. The children are left to form their own opinions, tastes, and moral codes. After having seen this film, on the photography of which the British Instructional Films are to be congratulated, I came away wishing with all my heart that my own dull schooldays had been as theirs are, and that education could be made such an adventure for every child.

Much of this was an accurate reflection of the radical educational experiment Pyke had set up. For most children it really was as if their dreams had come true. But as a promotional film there was no mention of any of the school’s difficulties.

‘Moulds are wrong,’ Pyke had once said, ‘and shaping is wrong, whatever it may aim at.’ Yet his belief that every child was a scientist in the making had permeated the school, and although he scoffed at the idea of parents pressing their cultural inheritances onto their children, he was gently moulding his son and the other children at Malting House into idealised versions of himself: free-thinkers with scientific outlooks who could one day reminisce on healthy and non-traumatic childhoods. There was nothing wrong with this, perhaps, but it illustrates one of the small slippages between theory and practice at Malting House.

A more telling gap had opened up between how the children were supposed to react to a life without rules and how they actually reacted. Beyond a certain age it was clear that some children needed clearer boundaries.

‘We want to be made to do definite things as they are in other schools,’ one seven-year-old complained at a fractious staff meeting, having just threatened to hit one of the grown-ups. This same child was asked why he wanted to be made to do definite things.

‘Because we don’t do anything otherwise. After all, what’s a school for?’

He was then asked to draw up a timetable, which he did, before summing up his feelings as follows: ‘I want to be made to do what I want to do.’ This perfectly embodies the sometimes paradoxical nature of our relationship with rules, no matter how old we are. These children wanted boundaries, boundaries of their own choosing, but boundaries all the same, and they wanted them to be enforced. This went against the school’s philosophy.

Another problem, though less obvious, was the extent of Pyke’s largesse. Even he would later admit to managing the school during this period ‘extravagantly’ and ‘irrespective of money’. Although he continued to spend within his means, his liquidity was greatly reduced. While he was not in debt, he had never been so vulnerable financially.

Having gained control of most of the world’s supply, the CEI cartel squeezed up the price of copper from £54 a ton earlier that year to £60 by October. Pyke had never seen the price behave like this. Nor had he ever pitted himself against an international cartel. It would be a severe test of his market prowess.

Earlier that month he had bought a large quantity of copper and, later, a sizeable holding of tin. The market was up. According to his model, the next move should have been to sell his copper on the basis that the price would soon drop. But he did not. Second-guessing the cartel, he hung on to the copper, thinking that the CEI was only interested in growing or stabilising the price, a decision he later described as a mixture of ‘imbecility and commercial rashness’.

The order of subsequent events is hard to reconstruct. Either the cartel flooded the market with copper or one of Pyke’s brokers got wind of his exposure and began to offload, with other brokers following suit. Most likely, it was a combination of the two. The price of copper plummeted, followed by the price of tin and lead, leaving Pyke with no choice but to hold on to what he had in the hope of weathering the storm. With the metals market in freefall one of his brokers asked for cover. Hopelessly over-leveraged and with very little liquidity, Pyke had no way of providing it short of selling up. Doing so, of course, would merely depress the price further and worsen his position. As he stalled, his other two brokers came in for cover. It was at this point in the history of Malting House that Susie Isaacs resigned.

The difficulties between her and Pyke had become more pronounced over the last ten months. It had begun with trifles over missed appointments and the ghost of a disagreement about who was taking more credit for the success of the school. Periods of calm would be punctured by rows in which both hurled torrents of half-remembered slights at each other before apologising and carrying on as if nothing had happened. The subtext to this was the way in which their affair had ended. Pyke resented the idea that Susie had both started it and finished it, which seemed to induce in her a scintilla of guilt to add to any feelings of inadequacy she might have had owing to their difficulties in bed. When she heard that Pyke had gone to Switzerland to see another woman after the end of their affair she had felt a pang of jealousy. All this had the strange effect of making her not only more tolerant of his unreasonable behaviour in between rows, but angrier when they came to argue.

‘I don’t want to hurt you,’ he told her, after she had begun to cry. ‘But I’ve been hurt too. There’s a limit to endurance. You’ve pushed a knife in me and screwed it round!’

She had done no such thing, but when the world appeared to be collapsing around him Pyke looked for a scapegoat. Susie was the obvious target.

By now Nathan knew about the affair and, following Susie’s resignation, he sent Margaret a sixty-eight-page letter in which he described himself as ‘quite naturally displaced’ and ‘full of admiration for Geoff’. ‘I’ve no resentment against Geoff,’ he went on, feeling only that his judgement had gone awry. The crux of the problem, he explained – Pyke’s greatest asset and at the same time the source of his self-destruction – was ‘the free play of that magnificent instrument, his mind. [. . .] More than anyone else I know [he] needs to be on his guard against the very powers of his mind.’ Magnificent it might have been, but it was hard to see how even Pyke could find a way out of the mess he was now in.

The first decline and fall of Geoffrey Pyke was halting and slow; it lasted nearly two years and by the end there seemed to be no further to fall. Unable to provide cover to his three brokers, Pyke’s trading companies had all gone into liquidation by the start of 1928. As sole guarantor he faced claims against him of £72,701, more than £2.2 million in today’s money. He had no way of paying it back.

Pyke did everything possible to save Malting House, making advance payments to the staff and disappearing to Switzerland for two months to delay the issue of writs. Cambridge friends rallied round and donations came in from parents as well as the likes of Siegfried Sassoon, Victor Rothschild and Victor Gollancz. But it was not enough.

After the school received a glowing write-up in the New York Times, Pyke applied for a grant from the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Trust with a covering letter signed by a group of worthies later described as ‘possibly the greatest galaxy of academic figures of the day ever assembled for a private fund-raising scheme’. It was to no avail.

The year after his personal financial crash Pyke was declared bankrupt, and in January 1929 the public bankruptcy hearings began. Lawyers acting for the brokers picked over his activities in what felt like a protracted judgement on his life and on the school into which he had poured at least £11,000 – referred to witheringly in court as his ‘great scheme’.

Certainly there were problems in the conception of Malting House. At least one of the children there, Jack Pole, who went on to become a renowned historian, would look back on his time there with bitterness. Yet for the majority of children this was a sunny, magical period that could only be appreciated once it had passed. One teacher wrote of the school that she had ‘never seen so much pleased concentration, so many shrieks and gurgles and jumpings for joy as here’. It was in the field of educational theory, however, that the impact of Malting House was most keenly felt on account of the mountainous records kept from the start. As Pyke had always hoped, the school became a starting point for further research. What he may not have appreciated, given the unhappy end to their relationship, was that most of this analysis would be done by Susie Isaacs.

Her study of the Malting House data formed the basis of her books, Social Development in Young Children and Intellectual Growth in Young Children, which secured her reputation as arguably ‘the greatest influence on British education in the twentieth century’. The same data provided the impetus for Sir Percy Nunn’s Department of Child Development at the University of London that went on to play a key role in the development of primary education in post-war Britain.

Yet for the barristers in the Bankruptcy Court in 1929 the only question that mattered was whether the school had played a part in Pyke’s tax-reduction scheme. Without full details of his accounts, it is impossible to say one way or another. What does become clear from the transcript of his examination is that Pyke was determined not to be pinned down. He was in escapologist mode. Even when the most damning evidence was read out to him about the tax advice he had received from the Soviet stooge D. N. Pritt, he would not yield to its meaning. Pyke was on top of his facts and light on his feet, exceptionally so. He infuriated his examiners by picking apart their questions, at one point informing a barrister that the question he had just been asked was in fact a statement delivered with a questioning lilt. Another time he asked the barrister to improve the wording of his inquiry.

‘Quibbling again?’ came the reply.

‘Accuracy,’ said Pyke.

‘No, quibbling again.’

‘No, one meaning to one question.’

And on it went.

At one point he was accused of presenting the court with a ‘tissue of falsehoods’, and there is no doubt that he was obscuring some key details in the arrangements between him and those shareholders from whom he had bought share options at inflated prices. Yet before the truth of this could be established, at the end of a particularly long session, Pyke collapsed.

Owing to the bankrupt’s ‘indisposition’, described elsewhere as a ‘sudden illness’, the hearing was adjourned until the following month. Only days before he was due in court again Pyke wrote to say that he was ill. The date of the hearing was pushed back once again and the night before he was due to appear, 22 April 1929, Pyke might have tried to kill himself.

A note signed by two doctors shortly afterwards described him as ‘dangerously ill and in my opinion [he] may not live through the night’. There is no further clue as to what happened, only the possibility that he had attempted suicide. The session was adjourned once more and Pyke was moved to a nursing home in Muswell Hill, from where a signed affidavit was sent to the court describing the patient as ‘suffering from paranoia (bordering on insanity), amnesia, fits of melancholia and incapability of severe mental effort’, so that ‘he will not be fit to attend to any business or legal affairs for at least twelve months’.

While there is a minute chance that Pyke had either fooled or persuaded a doctor to write this note, now that the barristers were closing in, this was almost certainly a genuine breakdown. Since he had been struck by what was thought to be pneumonia in Ruhleben he had experienced periodic bouts of chronic inertia accompanied by an overpowering sense of melancholy, so bad that there were times when he could not get out of bed. The strained circumstances of watching his life fall apart might have induced or exacerbated one of these episodes.

In July 1929 Margaret Pyke confirmed to the court that her husband was ‘bordering upon insanity’. In the same month the school’s scientific appointee sued him for unpaid wages. It was also around this time that Malting House closed its doors for good.

Geoffrey Pyke was bankrupt, he was being sued, his experimental school had closed, he was living in a nursing home and had been described as borderline insane. But still he had not reached rock bottom. During the winter of 1929, with the global economy entering meltdown, his wife left him.

We will never know all the reasons for this. Pyke’s affair with Susie must have played a part in their separation, and there is the possibility that Margaret had an abortion in the years after David’s birth, and that it was Pyke who had first suggested this. Yet we know that she was never again in a relationship with a man, and that rather than get divorced they remained amicably separated for the rest of their lives.

In a potted biography of Margaret Pyke published long after her death the reader is told that ‘her husband died in 1929’. He did not. And yet, a version of Pyke came to an end. During his first thirty-five years as an energetic Futurist in love with the scientific method, Geoffrey Pyke had tricked his way into and out of an enemy nation and had tasted life as a correspondent, best-selling author, minor Bloomsberry, financial speculator and radical educationalist. He had ridden waves of desire and rejection, jealousy and lust, living throughout as if with one layer of skin removed, and as a parent he had staked everything on the possibility of providing his son with an upbringing that was better than his own. His life was characterised by a propensity for taking enormous risks to achieve the seemingly impossible. Here was someone who inhabited the world as if it were an enormous game in which the rules were still being worked out. Now that game seemed to be over. In many ways it helps to think of this moment in his life as a death, for if he was to return to the stage he would need to do so as a man reborn.