Photograph of architect Frank Lloyd Wright (circa 1926). Library of Congress (LOC) Prints and Photographs.

1

MASON CITY, KINDERGARTEN AND THE IMPERIAL HOTEL

On the first day of September 1923, an American businessman named Walter Scott Rooney (the father of CBS news commentator Andy Rooney) was in his room at the new Imperial Hotel in downtown Tokyo, Japan.15

The hotel had been designed by American architect Frank Lloyd Wright, and this was its formal opening day. At two minutes before noon, as Rooney was sitting at a table enjoying a cup of tea, the building suddenly started to shake so violently that the tea spilled out.

In the moments that followed, Tokyo was ripped apart by a massive earthquake, followed by aftershocks, fires and turbulent winds. It was one of the largest, most catastrophic earthquakes in modern history, resulting in as many as 150,000 deaths.

Photograph of architect Frank Lloyd Wright (circa 1926). Library of Congress (LOC) Prints and Photographs.

Reconstruction of the main lobby of Wright’s Imperial Hotel (circa 2015) at Meiji-mura in Inuyama, Japan. Photograph by Bariston (Wikimedia Commons).

Wright was in Chicago that day. Eighteen months earlier, he had been in Tokyo, when the city was struck by a previous earthquake (the largest in thirty years at the time). The building was “in convulsions,” Wright wrote, yet he offered reassurances that the structure was purposely built to withstand any earthquake of any magnitude.16

Now, on the day of the building’s premiere, Wright’s credibility was at stake. Had the Imperial Hotel survived? Was it still standing? There were erroneous rumors that the structure had collapsed. But communications had been blocked, and for a number of days, Wright “walked the floor, inconsolable,” awaiting a factual update.17

In time, confirmation came that the Imperial Hotel was among the few buildings still standing. Not only had it survived the earthquake, but it had even been used as a refuge for displaced victims. Still, news reports continued to claim that it had been substantially damaged. The truth was somewhere in between.

TIES TO MASON CITY

In an effort to quell the rumors, Wright reached out to a California-based public relations expert named Merle Armitage, who was also an acquaintance. Armitage was “an old friend” of the architect’s son, Frank Lloyd Wright Jr. (known professionally as Lloyd Wright), who was working at the time as a Hollywood film set designer and residential architect.18

Armitage was a book designer and arts impresario, the manager of the Los Angeles Philharmonic Auditorium and would also later become the art director of Look magazine. His promotional efforts on Wright’s behalf were presumably effective, and today it is widely conceded that Wright’s Imperial Hotel (although damaged) was largely resistant to earthquakes.

Whenever this curious story is told, it is rarely mentioned that Wright and Armitage had something else in common: both men had important ties to a small city in north-central Iowa. It was the county seat of Cerro Gordo County called Mason City.

Mason City was, in fact, Merle Armitage’s birthplace. Born in 1893 on a farm southeast of the city, he had grown up in that community, then resettled with his parents when his father (one of the earliest livestock farmers to raise corn-fed beef cattle) moved his business interests to Lawrence, Kansas, and after that to Texas.

The Armitage family was no longer living in Mason City when, in 1908, in the course of several visits to the town, Frank Lloyd Wright was commissioned by two local attorneys, James E.E. Markley and James E. Blythe (both on the board of directors of a major city bank), to design a multipurpose building that would include a bank, an adjoining hotel, their own law offices and rentable retail spaces as well. Located beside a downtown park, the hotel was named the Park Inn, while the bank was officially known as the City National Bank.19

STOCKMAN HOUSE

On an early visit to Mason City, Wright was introduced to Dr. George and Eleanor (Chaffin) Stockman, a local physician and his wife who were Markley’s friends and neighbors.

Eleanor Stockman was an impassioned advocate of the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Her sister, Fannie Chaffin, was a longtime secretary to that organization’s president, Carrie Chapman Catt. The latter had grown up in nearby Charles City, Iowa, and had also recently served as a teacher and the first superintendent of schools in Mason City.20

Two views of the George C. Stockman House in Mason City, Iowa, in 2007. Photographs by Pamela V. White (Wikimedia Commons).

The Stockmans approached Wright about designing a two-story, four-bedroom home, both compact and affordable. In response, Wright proposed that he rework an existing plan that he had already published in the Ladies’ Home Journal called “A Fireproof House for $5,000.”21

Prior to that, as early as 1903, one of Wright’s associates, Walter Burley Griffin (while employed in Wright’s studio), had used a similar building plan for the Robert Lamp House in Madison, Wisconsin. A shared characteristic of these and other comparable homes is their “open floor plan” in which there are no dividing walls between the living room and dining room. As a result, these critical zones of activity blend into an L-shape, with a family hearth in the center.22

The Stockman House (as it is now commonly known) was completed in 1908. By 1924, Dr. Stockman had retired, and both he and his wife were failing in health. After Eleanor Stockman died that year, the house was sold. In subsequent years, it passed from owner to owner until 1987. Increasingly in disrepair and threatened with demolition (to make way for a church parking lot), it was heroically rescued by a civic-minded community group, which in 1989 moved it to a setting four blocks down the street, raised funds to restore it and opened it as a museum in 1992. By that remarkable effort, a modest yet pivotal landmark was saved for future generations.23

Through continued efforts by the River City Society for Historic Preservation, adjacent property was acquired just north of the Stockman House, and in 2011, the Robert E. McCoy Architectural Interpretive Center was completed. Designed by Iowa architect Robert Broshar in a manner that pays homage to both Frank Lloyd Wright and Walter Burley Griffin, it functions year-round as a museum and gift shop facility that offers instructional lectures, collectibles and self-guided tours of all architectural highlights in Mason City.24

SUCCESS AND SCANDAL

In planning the City National Bank and Park Inn, Wright made use of what he had learned from previous building projects. Likewise, while working on these Mason City commissions, he gained in ways that strengthened his subsequent efforts, notably the Midway Gardens (in Chicago) and the Imperial Hotel (in Tokyo). Wright’s Mason City projects (the Stockman House and the City National Bank and Park Inn) were completed between 1908 and 1910.

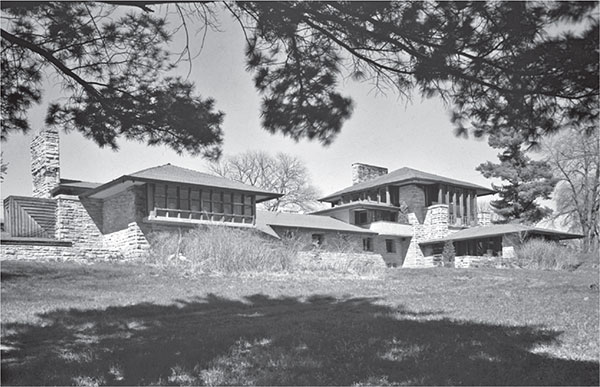

Frank Lloyd Wright’s home and studio in Oak Park, Illinois. Historic American Buildings Survey, LOC Prints and Photographs.

His Mason City clients were delighted with Wright’s accomplishments, and there were rumors of future commissions. But before any of those could be realized, he was publicly disgraced by an outrageous personal scandal, in the course of which he abandoned his wife and six children and went to Europe for a year with the wife of one of his clients.25

As it turned out, Wright had been in love for several years with an Oak Park neighbor named Martha (“Mamah”) Borthwick Cheney (pronounced “MAY-mah CHEE-ny”). Originally from Boone, Iowa, she herself was the mother of two young children.26

It was largely because of this scandal (gossip-laced reports of which were front-page stories in the news) that, as Katherine Rodeghier recently wrote in the Chicago Tribune, Wright “wasn’t exactly run out of town [Mason City]; he was asked never to return.”27 While some uncertainty remains, it is usually assumed that Wright never again set foot in Mason City. While he undoubtedly had access to photographs of the finished buildings, it may be that he never saw the City National Bank and Park Inn in their completed physical state.

In October 1909, Wright and Mamah Borthwick Cheney hurriedly left for Europe.28 During their year-long absence, the actual construction of the Mason City bank and inn was managed by a Wright associate, Chicago architect William Drummond, who in addition agreed to take on the design of another Mason City residence: the Curtis Yelland House at 7 River Heights Drive.29

Following Wright’s return from Europe in October 1910, he was commissioned to design the Midway Gardens, an elaborate concert garden and restaurant on Chicago’s South Side.30

Most likely, Wright and Merle Armitage first became acquainted in 1915. The latter was in Chicago that year, working as a manager and publicity agent for stage and concert performers. The great Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova was featured at the Midway Gardens several times that summer, in addition to other now legendary performers, including the Ballet Russes (Russian Ballet), operatic tenor Enrico Caruso and others.31

It was during this time that Wright’s career as an architect was substantially reestablished when he was commissioned to design the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo.

WRIGHT AND KINDERGARTEN

When and how did Frank Lloyd Wright, an up-and-coming architect from the burgeoning Windy City, become linked historically to a city as small and seemingly out of the way as Mason City, Iowa? One answer—believe it or not—is kindergarten.

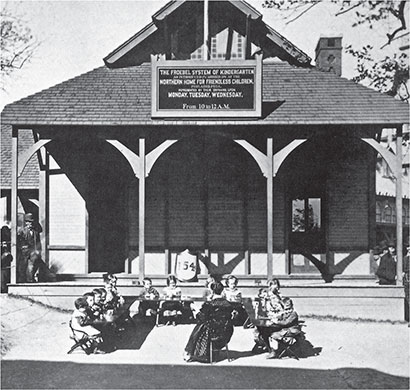

Kindergarten in this case does not refer to preschool as we know it now but to the original kindergarten (or “children’s garden”) of German educator Friedrich Froebel that began in Europe in the 1830s. Froebel’s kindergarten was not a literal garden (although, at times, its pupils did raise plants) but rather a radical new approach to early childhood teaching.32

Froebel challenged the customary practice of treating children as if they were adults in miniature, to be molded by rigid restrictions. To Froebel, children were first and foremost pliable minds. Having studied crystallography and forestry, he compared young children to immature plants.

Froebel believed that children, like seedlings, should be gently and patiently cared for. With tolerance and understanding, they should be helped to gradually learn and grow through participatory (“hands-on”) activities, such as singing, dancing and gardening—and by self-directed play.

It was Froebel’s idea, as once described by Arts and Crafts advocate Elbert Hubbard,

that the child was a human flower, and the school should be a garden where souls could blossom in the sunshine of love. …He [Froebel] utilized the tendency to play; just as we in degree use the tides of the sea and the winds that blow to turn the wheels of trade.33

Hubbard, the now famous founder of the Roycroft artists’ community in East Aurora, New York, had known Frank Lloyd Wright in Chicago. He had also been a vice-president of the Larkin Company, a pioneering and hugely successful mail-order firm in Buffalo, New York, for which Wright designed, in 1904, the acclaimed Larkin Building, the company’s administrative offices. Soon after, Wright also designed private homes for several Larkin executives, two of whom were married to Hubbard’s sisters, including John D. Larkin, the company’s chief executive officer.34

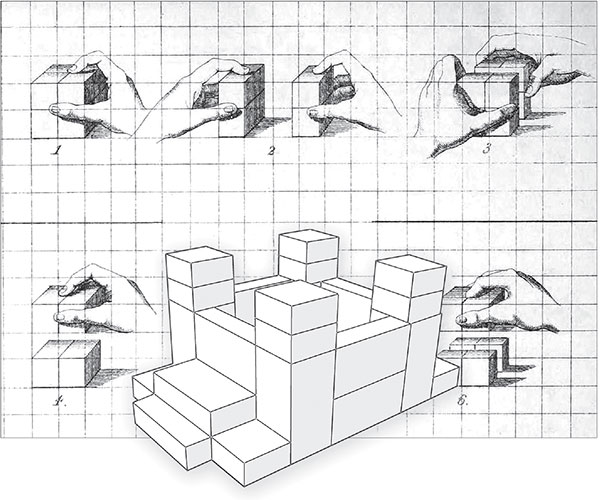

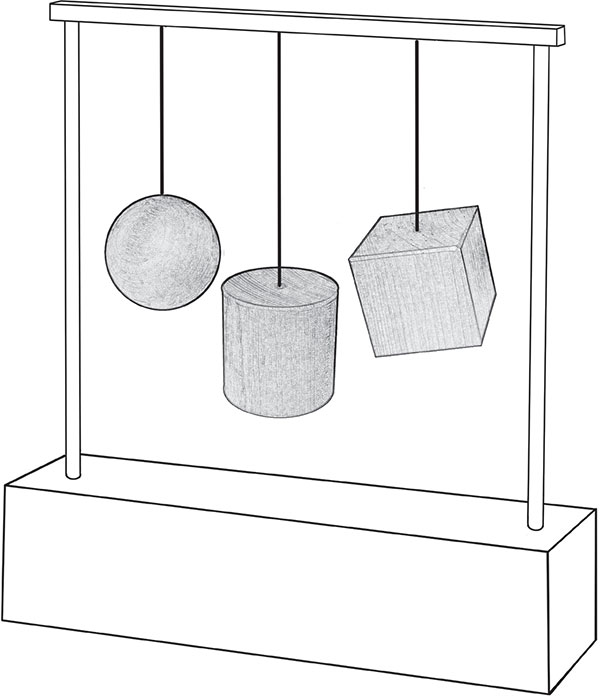

In the background is a page from a kindergarten teacher’s guide on the use of wooden blocks, while the foreground shows one result. Author’s diagram.

Having been influenced by the aesthetic movement, Hubbard and Wright (and Griffin) dressed “like artists,” wearing longish page-boy hairstyles and conspicuous Buster Brown cravats.35

To facilitate hands-on learning, Froebel devised a series of educational toys called “gifts.” Over time, each of his pupils was given the same set of these components (about twenty), one at a time, in a deliberate sequence.36

The most familiar of these were his famous sets of wooden blocks (smooth, unpainted maple blocks with no carved letters or other designs), which each child could put together in various ways to produce the widest variety of combinations.

Froebel had begun his own kindergarten in Germany in the late 1830s, but it quickly spread across Europe and to other continents. In 1856, the first American kindergarten (German speaking) was started in Watertown, Wisconsin, less than ten miles from Ixonia, where Wright’s ancestors settled. Less than twenty years later, there were 556 kindergartens in the United States.37

ORIGIN AND BELIEFS

Frank Lloyd Wright was born Frank Lincoln Wright in Wisconsin in 1867 (for years, he listed his birth year as 1869, but records indicate otherwise) and grew up near Richland Center, about one hundred miles from Watertown, site of the country’s first kindergarten.38 His mother (née Anna Lloyd Jones) had been trained as a teacher, while his father (William Wright) was a traveling Baptist preacher and musician.

Unfortunately, his father’s inability to provide a reliable income (plus other complications, not always the fault of his father) eventually contributed to William Wright’s departure from the family (at his wife’s suggestion) and the collapse of the couple’s marriage. Coincident with the ensuing divorce (filed by his father and not contested), son Frank changed his middle name from Lincoln to Lloyd, as a way to spurn his father and to underscore his loyalty to his mother’s family.39

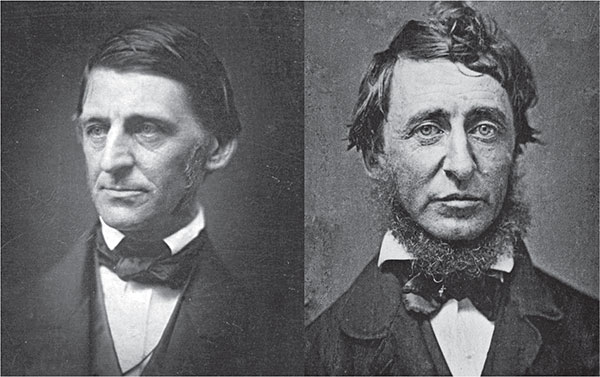

In contrast to his father, Wright’s mother and her relatives were wealthy, self-assured and well established. Of Welsh ancestry, they were impassioned free-thinkers who lived by the motto “The truth against the world.”40 They were outspoken adherents of Unitarianism and admirers of the writings of the New England transcendentalists, the most famous of whom were Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau and Margaret Fuller.

Transcendentalists Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. Wikimedia Commons.

Wright’s uncle (his mother’s brother) was Jenkin Lloyd Jones (“Uncle Jenk”), founder and longtime patriarch of the All Souls Church in Chicago, a church that welcomed all faiths, Christian or otherwise. He also traveled to midwestern cities, including Mason City, Iowa, to proselytize.

In Mason City, among Uncle Jenk’s acquaintances was Mary Emsley, James E.E. Markley’s mother-in-law, a staunch Unitarian and ardent suffragist who sometimes traveled to Richland Center, Wisconsin, to attend Jones’s Chautauqua presentations.41

Wright’s mother had two unmarried sisters, Ellen (Nell) and Jane Lloyd Jones, who were also teachers. In 1887, they founded a progressive coeducational school on the Lloyd Jones family estate, about twenty-five miles from Richland Center, near Spring Green.

The six-hundred-acre family estate was in Jones Valley, which local people sarcastically called “the valley of the God-Almighty Joneses.”42 The property had been acquired by Wright’s maternal grandfather in the mid-nineteenth century.

Wright’s aunts’ school, called Hillside Home School, was initially housed in a wood-frame, Shingle-style building designed by their architect nephew at age nineteen. Years later, he designed an alternative building of stone. The construction of that second building was supervised by Wright associate Walter Burley Griffin (who would later play a central role in Mason City architecture). It officially opened in 1902.

That same year, one of the daughters of Mason City’s James E.E. and Lilly (Emsley) Markley (who would advocate commissioning Wright to design the City National Bank and Park Inn) enrolled as a student there. Soon after, a second daughter enrolled as well.43

FROEBEL AT THE WORLD’S FAIR

A quarter of a century earlier, in 1876, Frank Lloyd Wright’s mother had attended the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, a one-hundred-year celebration of the origins of the United States.44

While there, she saw an exhibition about the kindergarten movement and soon after bought a set of Froebel blocks (which by then were being sold by game manufacturer Milton Bradley). She shared these with her son and two daughters, but especially with Frank, whom she had predicted (even before he was actually born) would grow up to be an architect.

Visitors to the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia were able to observe a kindergarten class. LOC Prints and Photographs.

Of course, Wright’s mother had no way of knowing just how true her prediction would be. In 1991, more than thirty years after Wright’s death, he would be officially honored as “the greatest American architect of all time” by the American Institute of Architects—an organization that, during his lifetime, he had frequently poked fun at and refused to be a member of. Much earlier than that, on January 17, 1938, he had also been featured on the cover of Time magazine.

In his writings, Wright repeatedly remembered how his mother had introduced him to Froebel’s geometric blocks, long after kindergarten age, most likely when he was nine or ten: “For several years I sat at the little kindergarten table top…and played…[with] these smooth wooden maple blocks. …[They] are in my fingers to this day.”45

As documented by Norman Brosterman, Wright was one of a number of European and American artists, designers and architects (and those in other professions as well) from the same time period who, as children, were introduced to Froebel’s blocks and comparable construction toys.46 In Wright’s case, the influence was doubly strong because, later, as a parent, he introduced his own children to Froebel’s gifts.

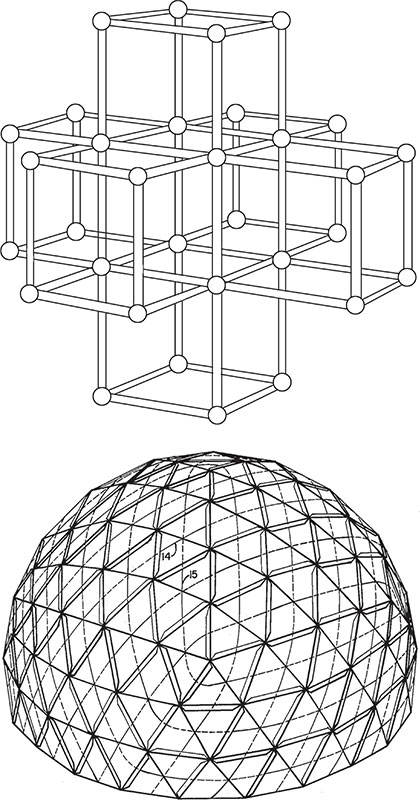

In one of the gifts, known as “peas-work,” children were provided with a supply of dried peas (or small cork cubes or balls of wax) and toothpicks, with which they could assemble forms.47 Most likely, the Tinkertoy Construction Set, even if indirectly, was influenced by Froebel’s peas-work gift, although its immediate model is said to have been sticks and empty spools of thread.

Wright had fond memories of his encounters with hands-on toys like peas-work. But even more greatly influenced by these was architect-engineer R. Buckminster Fuller (interestingly, he was the grandnephew of New England transcendentalist Margaret Fuller).

Born cross-eyed and abnormally farsighted, Fuller (in his own words) “could only see large patterns, houses, trees and outlines of people. …I could see two dark areas on human faces, but I could not see a human eye or a teardrop or a human hair.”48

In kindergarten, Buckminster Fuller made peas and toothpick constructions (top), then later used the same method in his geodesic dome (bottom). Author’s diagram and U.S. Patent 3,203,144, U.S. Patent Office.

When Fuller’s kindergarten group was given peas and toothpicks, the majority of his classmates made rectangles and cubes, the first solutions that sprang to mind.

Given his visual impairment, Fuller chose instead to make a triangular unit (the “octet truss”), which is structurally stronger and which he would later use as the module for his famous geodesic dome. That same year, he was also fitted with powerful Coke bottle glasses, but even after that, he recalled, “my childhood’s spontaneous dependence only upon big patterns has persisted.”49

Throughout his life, whenever Frank Lloyd Wright was asked what experiences had contributed to his development as an architect, he invariably responded that his two greatest influences had been Froebel’s kindergarten blocks and Japanese Ukiyo-e woodcut prints (of which he was a collector and dealer). It is now commonly claimed that these two factors were part of what enabled Wright to see architectural shapes as generic abstract forms, which he called “constructive patterns.”50

Throughout his career, unlike most people, Wright saw buildings as generalized patterns, as “big picture” whole effects, not as incidental parts. In his own words, he saw a building as “one great thing instead of a quarreling collection of so many little things.”51

Like Buckminster Fuller, Wright had learned to see holistically—to see layouts or gestalts, as do graphic designers. Their way of seeing was somewhat like looking through the wrong end of a telescope. It was a generalized, overall view—or, as the age-old maxim says, they saw the forest instead of the trees.

Recalling Wright’s achievements, as well as those of Fuller and others, a poignant passage comes to mind from William James’s Principles of Psychology, in which he said that “some people are far more sensitive to resemblances, and far more ready to point out wherein they consist, than others are. They are the wits, the poets, the inventors, the scientific men, the practical geniuses.”52

PRIMACY OF UNITY

In his autobiography, kindergarten founder Friedrich Froebel stated that “all is unity, all rests in unity, all springs from unity, strives for and leads up to unity, and returns to unity at last.”53

Early in his teaching career, Froebel had devised the second gift in his series, consisting of a wooden ball and a cube, with a cylinder in between. This was his favorite of all the gifts, since none of the others so powerfully showed the unity of opposites.

The second kindergarten gift was Friedrich Froebel’s favorite, consisting of a wooden sphere, a cylinder and a cube. Author’s drawing.

A ball and a cube are typically assumed to be radically different shape types, yet Froebel in the second gift showed that both those fundamental shapes are found within the cylinder. The cylinder looks circular when viewed from the end but looks square like a cube when observed from the side. Further, when suspended from a string or transformed into spinning tops, these shapes look even more alike.

Regarding this second gift, Brosterman has said:

Without mirrors, nothing up his sleeve, and right before their eyes, Froebel, in a sleight-of-hand worthy of a resourceful magician, created the ultimate gambit—a straightforward demonstration of cosmic mutuality and universal connectedness that even a child could understand.54

If Wright’s way of looking is indebted to Froebel, he was just as strongly influenced by Unitarianism and transcendentalism, which were related but differing trends at the close of the nineteenth century.

All three phenomena (kindergarten, Unitarianism and transcendentalism) had attributes that confirmed their connectedness, the most important of which was unity. It is not surprising, then, that the person who founded the first English-language kindergarten in the United States, Elizabeth Palmer Peabody, was a leading transcendentalist and an associate of Margaret Fuller.

In Wright’s autobiography, when he described the Unitarianism of his Lloyd Jones relatives (whose meeting places bore such names as Unity Temple, Unity Church and Unity Chapel), he said, “Unity was their watchword, the sign and symbol that thrilled them, the unity of all things.”55

In the transcendentalism of Emerson and Thoreau—as well as in other traditions that emphasize the bond between spirituality and nature—there was no rigid distinction between man and nature.

Thoreau once told a story about a sparrow that “alight[ed] on my shoulder for a moment, while I was hoeing in a village garden, and I felt that I was more distinguished by that circumstance than I should have been by any epaulet I could have worn.”56

To the transcendentalists, we are one with nature. In Wright’s case, he repeatedly expressed the view that nature is a manifestation of God and that “Nature should be spelled with a capital N.”57 Spirituality is attendant at all times and in all places so that a person might worship alone in the woods as suitably as congregate in a designated meeting hall on a particular day of the week.

It may seem ironic that Wright designed a number of churches (including synagogues) during his life for a variety of religious groups, not just Unitarians. In 1957, in an interview with television journalist Mike Wallace, when asked if he attended church, Wright replied, “I attend the greatest of all churches”—by which, of course, he meant Nature.58

As a result, he continued, he was free “to build churches for other people,” in the sense that “if I belonged to any one church, they couldn’t ask me to build a church for them. But because my church is elemental, fundamental, I can build [a place of worship] for anybody.”59

EUROPEAN INTERLUDE

When Frank Lloyd Wright and Mamah Borthwick Cheney left hurriedly for Europe in October 1909, it was not just to escape the lurid accounts of their personal lives in American newspapers.

There were other reasons as well, foremost of which was an opportunity for Wright to travel to Berlin (he had never visited Europe before) and to collaborate with a prestigious publisher named Ernst Wasmuth in producing a large-format, two-volume folio of his finest architectural work, spanning from 1893 through 1909.60

The first volume of this publication began with an introduction by Wright, essentially amounting to a manifesto for what would in time become well known as Prairie School architecture.

When initially published, the German title of that first volume was Ausgeführte Bauten und Entwürfe von Frank Lloyd Wright (Drawings and Plans of Frank Lloyd Wright), but it soon became widely referred to as the Wasmuth Portfolio.61

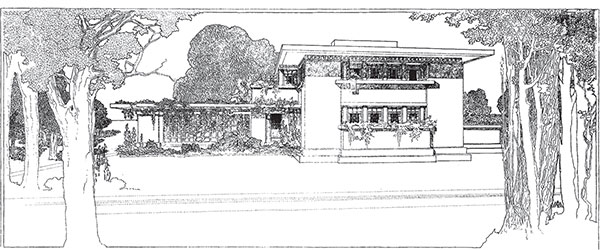

Featured in the Wasmuth Portfolio were numerous line-work lithographs of his architectural projects, with floor plans and perspective views. Among the projects that were prominently featured were Wright’s three buildings in Mason City: the Stockman House and the City National Bank and Park Inn.

Of the book’s illustrations, about half were rendered by Marion Mahony, one of the most talented associates in Wright’s Oak Park architectural firm. These drawings were purposely similar to Japanese Ukiyo-e woodcuts. As Wright himself admitted, their indebtedness “to Japanese ideals, these renderings themselves sufficiently acknowledge.”62

Wright’s design for “A Fireproof Home for $5,000,” the plans for which were used for the Stockman House, among others. Wasmuth Portfolio (1910).

Mahony was among the first women to study architecture at MIT and one of the first to become a licensed American architect. Hired by Wright in 1895, for fifteen years she was a vital contributor (albeit in the background) to his architectural triumphs and later even more so to the subsequent achievements of Walter Burley Griffin, who began to work for Wright in 1901 and whom she married in 1911.

In fact, it was Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin, more than Wright, who solidified the legacy of Mason City (and Rock Crest/ Rock Glen specifically) as an architectural landmark—one that scholar Paul Kruty described as “a timeless masterpiece melding landscape, planning, and architecture.”63

The importance of the Wasmuth Portfolio to Frank Lloyd Wright’s career cannot be overstated. When he left for Europe, he was already in his forties. While his work had not been ignored in America (it had been featured in various periodicals, as well as in a monograph), it was at best insufficiently praised, and by 1909, debates about his architecture were outpaced by the gossip regarding his life.

The Wasmuth Portfolio was the first international showcase of Wright’s architecture, and it served as a two-pronged occasion: It called attention to his work among American architects when they saw it regarded so seriously by a prestigious audience from abroad.64 At the same time, it introduced his achievements to a generation of young European architects, who immediately sensed the connections between Wright and their own explorations.

Among young architects at the time, the most sought-after place of training and employment in Germany was the studio of architect and designer Peter Behrens, who had recently taken on the role of the first corporate designer in history.

In 1907, Behrens had been retained as “artistic advisor” (design director) for the company AEG (Allgemeine Elektrizitäts-Gesellschaft, or German General Electric).

In that capacity, Behrens’ studio was responsible for developing the “brand” of the company, the “style” of what it stood for—its corporate logo, its products, its packaging and its advertising.

He was also its chief architect, most notably in 1910, when he designed the famous AEG Turbine Factory.65

ARTS AND CRAFTS MOVEMENT

Initially trained as an artist, Behrens had gradually turned to architecture, interwoven with art and design. In so doing, he was only one of many artists turned designers whose careers had been inspired by the example of British designer William Morris.

Morris was the revered patriarch of the Arts and Crafts movement, so named because it tried to soften the arrogant class distinctions between glorified “artists” and denigrated “craftsmen,” the lowly designers of functional things.

Morris’ efforts had begun in the late 1850s, when he took on the responsibility of furnishing his own new home, called Red House (designed for Morris and his bride by his architect friend Philip Webb). Soon after, he established Morris and Company, a design firm that produced a wide range of interior accessories, such as wall tapestries, textiles, wallpaper, art glass windows and furniture.66

In 1895, inspired by Morris’ example, a Belgian-born artist turned architect/designer named Henry van de Velde designed his own home (called Bloemenwerf) outside Brussels and produced its interior furnishings, too.67 Four years later, this idea was taken further by none other than Peter Behrens, who designed his home (called Behrens Haus), as well as its furnishings and accessories.

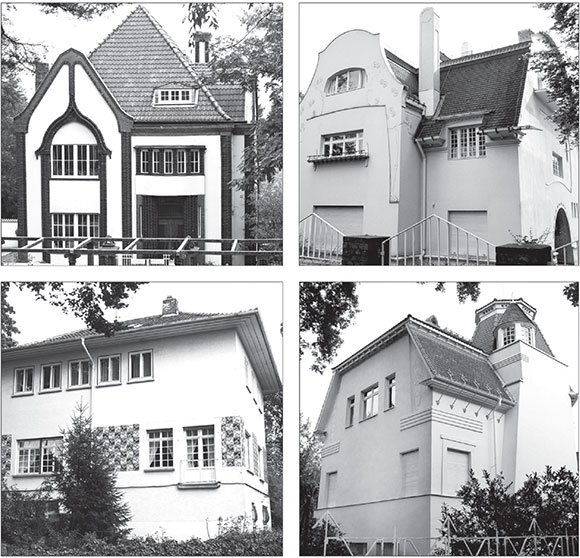

It is important to realize that Behrens’ house was one of seven experimental residences in a planned community setting in Darmstadt, Germany, known as the Darmstadt Artists’ Colony. Located on a hill above the city (called Mathildenhöhe), the neighborhood opened officially in 1901.68

This cluster of Darmstadt artists’ homes is of particular relevance here because, in ways, it was a precedent for what would take place in Mason City a decade later.

It was at that time, after the completion of the City National Bank and Park Inn Hotel (by which point Wright had been dismissed), that Wright’s former associate Walter Burley Griffin was commissioned to design an architectural neighborhood in Mason City (to be known as Rock Crest/Rock Glen), within which were constructed a group of gem-like Prairie School homes.

It is of additional interest because, while Wright was visiting Germany, he made a targeted effort to visit the Darmstadt Artists’ Colony, where most of the homes (with the exception of Behrens’ house) had been designed by Josef Maria Olbrich, an Austrian architect who had co-founded the Vienna Secession and designed the famous Secession Building in Vienna.69

Houses in the Darmstadt Artists’ Colony (circa 1901). At top left is Peter Behrens’ house. The remaining three were designed by Josef Maria Olbrich. Photographs by Storflix (Wikimedia Commons).

Wright was acquainted with Olbrich’s designs, some of which had won prestigious prizes at the 1904 Exposition in St. Louis. Wright went to St. Louis to tour the exhibits there, which included works by Olbrich, Peter Behrens, Josef Hoffmann and other Europeans.70 When he returned to Chicago from St. Louis, he was so excited that he paid the travel expenses of one of his studio associates, Barry Byrne, to attend the exhibition himself.

Later, Byrne himself would play a role in the development of Mason City’s Rock Crest/Rock Glen community. In 1908, he worked briefly in the Griffin’s studio and then established his own practice in California.

In 1914, when Griffin and his wife, Marion Mahony, moved to Australia (permanently as it turned out) to design that country’s new capital of Canberra, Byrne was contracted to manage Griffin’s architectural firm. As a result, he guided the completion of the Rock Crest/Rock Glen neighborhood, where he is also credited with overseeing Griffin’s design (if not always as Griffin had planned) of several Prairie School houses, along with two designed by him.71

After arriving in Germany, Wright was eager to travel to Darmstadt to see its artist colony residences. While there, he had also hoped to meet Olbrich, not realizing that the forty-year-old architect had died of leukemia a few months earlier.72 It is often suggested that there are strong correlations between some of Olbrich’s earlier work (his Vienna Secession Building for one) and Wright’s Unity Temple and the Larkin Building. Did Olbrich influence Wright? Or did Wright influence the Europeans? No one knows for certain, and most likely we will never know. For whatever reason, Wright was surprised (and apparently not displeased) when he was introduced to German architects in Berlin as the “American Olbrich.”73

Today, Mason City is a treasure-trove of architectural delights. But it would not be quite so amazing if it could claim only to be the home of three Frank Lloyd Wright buildings.

Of equal significance is the Rock Crest/Rock Glen neighborhood, which is of greater distinction than is usually realized. That unique neighborhood, as architect Jonathan Lipman said, is “the major focus of Prairie architecture outside of Chicago…the largest collection of Prairie School houses unified by a common natural setting in the world.”74

When Griffin’s planned neighborhood is combined with Wright’s three buildings, it may not be undue to say that Mason City is an architectural heart of the prairie—a Darmstadt of the Middle West.

GESAMTKUNSTWERK

In Europe, among architects and designers in the late nineteenth century, the practice of designing a building as a coherently unified whole acquired the name of Gesamtkunstwerk.75

The term was used initially—outside of architecture—in 1847 and was soon after popularized by the German composer Richard Wagner, who used it as a tag line for elaborate performances (“opera and drama”) in which all the arts (dance, theater, music, literature and the visual arts) were combined in one production. Dissembling its German components—Gesamt means “total,” kunst means “art” and werk is “work”—the translation to English is “total work of art.”

Late in the nineteenth century, when the term was widely adopted among architects, it signified that it was no longer acceptable to merely plan a building’s shell (walls, rooms, doors and windows) and then sign off and be done with the project. Instead, a building should be a unified composition in which all its subsets are compatible with the total effect—beginning with the building site, its shell, its interior furnishings and other accessories.

Frank Lloyd Wright apparently spoke little, if any, German. In his writings, it is doubtful if he ever used the German word Gesamtkunstwerk, but in the Wasmuth Portfolio introduction, he talks about a dwelling as “a complete work of art.”76

An equivalent phrase that he frequently used was “organic form.” By that, he meant that all aspects of a building should have the same functional duality as parts of the body, words in a sentence or members of society.77

Each part should function as a whole, a discrete fragment, while at the same time contributing to a larger unit, a unified totality. While each part has its particular task (the thumb, for example, does certain things well, others not), it must also work for the good of the whole. The same can be said of ingredients that compose a house, a bank, a hotel or other structure.

“Organic,” according to Wright associate Barry Byrne, “was his favorite word. When you look at a tree, it is a magnificent example of an organic whole. All parts belong together, not by labels or intellectual means, they just belong, as fingers belong to one’s hands.”78

In the Wasmuth Portfolio, Wright said of organic architecture that “it is quite impossible to consider the building as one thing, its furnishings another and its setting and environment still another. The spirit, in which these buildings are conceived, sees all these together at work as one thing.”79

In reading this and other passages, while knowing that other European architects and designers (among them Henry van de Velde, Peter Behrens, Josef Maria Olbrich, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Josef Hoffmann, Gerrit Rietveld) were enchanted by the concept of Gesamtkunstwerk, one can imagine the fervor with which they and other architects read Wright’s inspiring essay on organic form and carefully studied his buildings as well.80

In Berlin, in the year Wright’s folio first appeared, there were twenty to thirty employees in Peter Behrens’ studio. Among his apprentices were people who would soon become some of the most famous architects of the twentieth century, among them Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius (who would later be founder-director of the Bauhaus, the most influential art and design school in modern history).

It is sometimes claimed (true or not) that in Behrens’ Berlin studio, when the Wasmuth Portfolio was released, the activities of the company were halted for the day so that the studio’s young architects could have sufficient time to study Wright’s publication.

ORGANIC FORM

In Europe, the public reaction to the practice of Gesamtkunstwerk was no less controversial than was Frank Lloyd Wright’s insistence on organic form. At one time or another, architects on both sides of the Atlantic were accused of taking it to extremes and of behaving despotically toward their clients.

Among those satirized was Belgian-born architect and designer Henry van de Velde, who designed not only his family’s home and all its furnishings but also matching outfits for his wife and children (intended to be worn at home).81

A famous apocryphal story reports that van de Velde once reproached a client who, although he was wearing the slippers designed by van de Velde to be worn in that house, was scolded for wearing them in the wrong room.

“They were designed to be worn in the bedroom!” he admonished his dumbfounded client.82

During these same years, Viennese artist/designer Gustav Klimt collaborated with his companion, Emilie Flöge, on the design of upscale, exquisitely designed “art dresses.”83

Likewise, Frank Lloyd Wright is said to have made architecturally appropriate outfits for his wife Catherine (of which photographs still exist), as well as for his clients’ wives in the Coonley, Robie and Dana homes.84

In the United States, Wright’s reputation (deserved or not) has often been one of intimidating his clients. Given his commitment to organic form, he probably would have preferred to have been even more inflexible in insisting on what was permissible in an idealized Wrightian setting.

This was a continuing problem because his clients too often assumed (after all, it was their home, which they had financed most likely at a greater cost than the architect had initially estimated) that they could fill up their new masterpiece with the tasteless stuff they already owned.

At one point, he suggested that “about four-fifths of the contents of nearly every home could be given away with good effect to that home. But the things given away might go on to poison some other home. So why not at once destroy undesirable things…make an end of them?”85

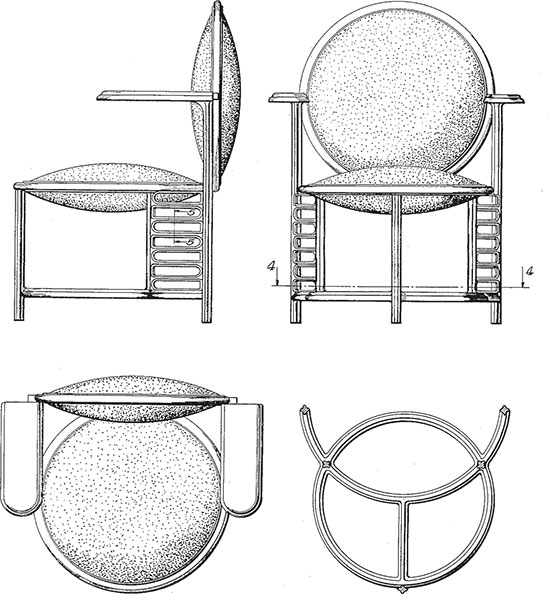

Patent drawings for Wright’s office chair for the Johnson Wax Office Building in Racine, Wisconsin (circa 1939). U.S. Patent D108,473, U.S. Patent Office.

Wright himself admitted that few of the houses he designed were “anything but painful to me after the clients moved in…[having] dragged [in] the horrors of the old order along after them.”86 From early on, he addressed this issue (as did others of the same era) by developing his own innovative furniture for each newly designed house.

At times, he was superbly successful at furniture design, and at other times, emphatically not. It was a formidable challenge to make an architectural style align with the functional requirements of furniture, with the result, as he conceded: “I have been black and blue in some spot, somewhere, almost all my life from too intimate contacts with my own furniture.”87

DESOLATION AND DESPAIR

The complete two-volume Wasmuth Portfolio was published in 1911, a few months after Wright returned to Chicago. By then, it was apparent that, unless he gave up his relationship with Mamah Borthwick Cheney and returned to his wife and children, he could not continue to live in Oak Park. He and Mamah would have to relocate.

As a solution, he decided he would design and construct a new Prairie School home (to be named Taliesin, which is Welsh for “shining brow”) near Spring Green, Wisconsin, in Jones Valley, on land that his mother had given to him.

The construction of Taliesin was promptly begun, and Wright and Mamah Borthwick (now divorced, she had reverted to her maiden name) moved into the living quarters in the winter of 1911. Meanwhile, Wright took on the design of the Midway Gardens in Chicago, in addition to other commissions. In 1913, he and Mamah traveled to Japan in order to purchase Ukiyo-e woodblock prints for art collectors. During the same trip, he also apparently met with Japanese officials to further discuss the design of the new Imperial Hotel in Tokyo.

And then, the most dreadful tragedy struck. On August 15, 1914, Mamah Borthwick was at Taliesin with her two visiting children (ten and eleven years old), while Wright was in Chicago, working with his architect son, John Lloyd Wright, on plans for the Midway Gardens. Other members of the Taliesin work crew at Spring Green were also present on the grounds.88

During the lunch hour, Borthwick and her children were savagely attacked and killed by a domestic servant, a “Barbados Negro” (Wright’s term, which is important to mention because the ethnicity of the assailant was invariably emphasized in newspaper reports) who was brandishing a shingling axe.

The assailant then set fire to the building, attacking others as they fled. Seven people were slain that day, others wounded, and much of Taliesin was destroyed.

Emotionally devastated—presumably in greater pain than before or ever again in his life—Wright and his son John returned by train to Spring Green to confront the horrifying reality.

To the credit of Wright and Edwin Cheney (Mamah Borthwick’s former husband), the two men made the trip together in a shared railway car—the former to bury the woman he loved and the latter to claim the severed remains of his murdered children.89

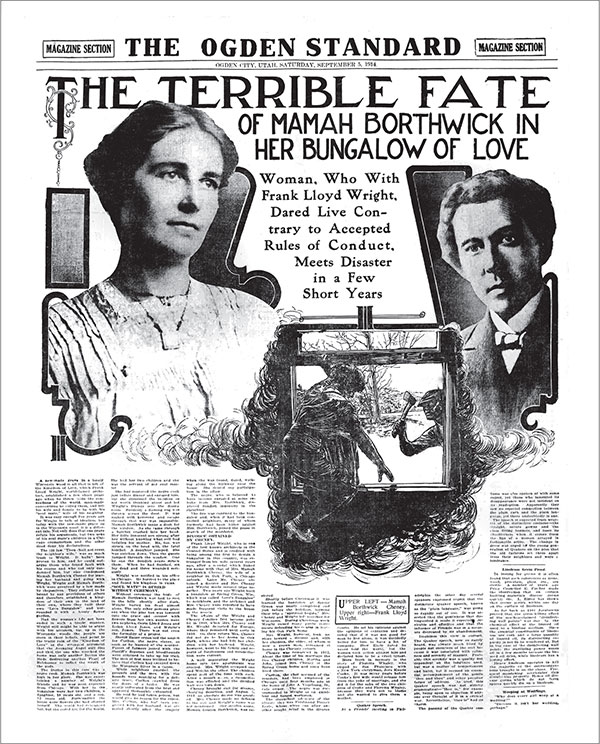

Not surprisingly, some of the newspaper stories about the murders were no less crude or lurid than had been the earlier articles on the couple’s romance.

Taliesin East near Spring Green, Wisconsin, after having been rebuilt. Historic American Buildings Survey, LOC Prints and Photographs.

Some newspapers even suggested that the slaying of Mamah Borthwick was retribution by the God of the Old Testament for their extramarital lustfulness. In the August 15 issue of the Detroit Tribune, an especially insensitive headline read: “NEGRO FIRES ‘LOVE BUNGALOW.’”

Two days after the attack, an account of the murders appeared on the front page of the Mason City Globe-Gazette. It included this sequence of headlines:

WRIGHT’S SOUL MATE IS SLAIN. INFURIATED NEGRO COOK KILLS THREE [sic] AT “LOVE BUNGALOW” OF MAN WELL KNOWN IN THIS CITY. CITY NATIONAL WAS DESIGNED BY WRIGHT. Famous Chicago Architect Who Attracted World-Wide Attention by Love Affairs, Planned Some of the Finest Buildings of Mason City, Including the Dr. Stockman House.

At the Taliesin crime scene, the fire continued to smolder for days, followed by a freak hailstorm, with more destruction being caused by water damage. In the basement, Wright had been storing the printing plates of the Wasmuth Portfolio and finished but unbound copies. In the end, only thirty undamaged copies survived.

Mamah Borthwick was buried quietly in the Lloyd Jones ancestral cemetery at Taliesin. At her grave site, Wright was left by himself in order to shovel dirt into the grave in solitude. There was no tombstone at the time. “Why mark the spot,” he later wrote, “where desolation ended and began?”90

Front page of the magazine section of the Ogden Standard (Ogden City, Utah), on September 4, 1914, describing the murders at Taliesin.

Looking back at that catastrophic episode in Wright’s life, there is no way to reconstruct—or to begin to imagine—his state of mind and the bewildering surge of emotions he felt.

As Brendan Gill, one of Wright’s biographers, wrote, it is not often that we pass, in a brief span of hours, “from the happiest moments of one’s life to the most despairing.”91