Ukiyo-e woodblock print, titled Moon-Viewing Point, by Utagawa Hiroshige (circa 1857). LOC Prints and Photographs.

2

MASON CITY MEETS MODERN DESIGN

However vast the distance—let alone the cultural gap—between London, England, and Mason City, Iowa, 1851 was a consequential year for both.

Iowa had been granted statehood in 1846. But it was not until five years later that Cerro Gordo County was founded by Euro-American settlers and their immigrant families, who constructed makeshift cabins near the present community of Clear Lake. The closest other settlements of white immigrants were fifty miles east in Chickasaw County.

Mason City is nine miles east of Clear Lake. Initially known by various names (Shibboleth, Masonic Grove, and Masonville), it was officially established in 1853. Before the end of the decade, it had become the county seat.92

At mid-century, the area’s white settlers had largely tranquil dealings with small bands of Native Americans who had traditionally summered near Clear Lake. When occasional violence did break out, it typically occurred between indigenous hostile nations, fueled by old, unsettled scores.

In the early 1850s, area settlers vacated the area briefly in response to events that were generally known as the Grindstone War. But of far greater concern was the killing by Native Americans in 1857 of about forty white settlers at Spirit Lake, Iowa (known by whites as the Spirit Lake Massacre), one hundred miles west of Mason City.93

Despite such setbacks, in an effort to encourage continued settlement, the U.S. government declared the area a neutral zone, open to white settlers but off limits to Native American groups.

Ukiyo-e woodblock print, titled Moon-Viewing Point, by Utagawa Hiroshige (circa 1857). LOC Prints and Photographs.

Predictably, the infusion of settlers continued, and by 1860, there were 940 Euro-Americans in Cerro Gordo County alone and, a decade later, nearly 5,000.

During the second half of the nineteenth century, as the population increased, the county and its residents were inextricably overwhelmed by the effects of the Industrial Revolution, which had begun in the previous century in England and other regions of Europe.

Before they knew what hit them, residents of Cerro Gordo County were profoundly and irreversibly changed by a torrent of innovation in manufacturing, transportation, communication, agriculture, finance, building materials—and architecture.

INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

In London, England, more than four thousand miles east of Mason City, the changes that took place in 1851 were even more momentous. It marked the opening of the first World’s Fair, an occasion officially titled the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations.94

Of lasting effect both culturally and economically, the fair was the first concerted attempt to promote industrial products to potential investors and buyers, as well as an opportunity for other countries to demonstrate their own achievements.

That first World’s Fair was also important architecturally because of the building in which it was housed. Erected temporarily in Hyde Park in central London, it was open to the public only from May to mid-October that year. A two-story, massive, eighteen-acre iron-and-glass enclosure, it was the world’s largest building at the time.

Designed by architect Joseph Paxton, an expert on botanical gardens, the building was essentially a gargantuan greenhouse, which explains why pundits called it the “Crystal Palace,” a name that caught on with the public as well. When the fair ended, the structure was dismantled, and its components were reassembled (in modified form) at Sydenham, a suburb of London, where it functioned for many years as a generic events center.

At the Hyde Park Crystal Palace, about fourteen thousand exhibits were shown. Just to walk through the exhibits was a distance of eight miles or more. The majority of items were sponsored by the British. But there were also notable entries from other countries, including the United States, among whose most popular products were McCormick’s reaper, the Colt revolver, Goodyear rubber products, reliable false teeth and chewing tobacco.

The Crystal Palace was essentially an eighteen-acre greenhouse made of machine-manufactured components. Vintage postcard.

Interior view (detail) of the Crystal Palace (1851). Public domain.

At the time, no one could have anticipated the success of the Crystal Palace, economic and otherwise. Queen Victoria loved it (and not just because it was the pet project of her husband, Prince Albert). She visited the fair at least three times, noting in her letters that it included every conceivable invention and was “incredibly glorious, really like fairyland.”95

In the end, the exhibition was attended by more than six million visitors (three times the population of London at the time), each of whom paid for admission. A financial loss had been anticipated, but it made an astonishing profit instead, which then led to a clamorous rush by other countries to host the next industrial fair.

INNOVATIVE FORERUNNER

It is often claimed that the Crystal Palace was a forerunner of modernism in architecture because of its building innovations (not for the gaudy kitsch products inside). It is even commonly said to have been the first Modern building for features we take for granted today.

For example, it was made of what we now regard as “modern” building materials—glass and iron—although the floor was made of wood. Its components were machine made, not handcrafted. Further, those same parts were mass produced in various factories and then transported to Hyde Park to be put together by workers at the site. The cast-iron and plate glass components were modular and standardized, as is the usual practice today.

Other features were early attempts at aligning form with function, as would later be championed by Chicago architect Louis H. Sullivan. As is well known, he would be the mentor of some of the leading Prairie School architects, including those who contributed to Mason City architecture, the most famous being Frank Lloyd Wright.

One of the problems encountered in designing the Crystal Palace was the preservation of ancient trees in Hyde Park. British politicians insisted that certain historic elms be spared so that the park could return to its earlier state after the fair had ended.

As a solution, Paxton preserved the living trees by including them inside the building—the walls were built around them. (Not surprisingly, there was a problem with sparrows inside—an issue that could be easily solved, someone suggested, by the addition of sparrow hawks.)

In this, and by using glass for the walls (through which one could see outside), the building was an early attempt at blurring the rigid distinctions between inside and outside or, as Wright would later say, at dissolving the boxlike confines of the house.

There was no electrical lighting in 1851, so how could there be adequate light in which to view the exhibits? As it turned out, natural lighting proved sufficient because the building was made of glass.

But that, in itself, caused a problem because the sunlight, in addition to the body heat of thousands of visitors, raised the interior temperature. Paxton’s solution was to install external adjustable shades, which were sprayed with water. He also used rudimentary air conditioning, produced by circulating air that rose up through intentional gaps in the floor.96

The Crystal Palace was an ingenious early attempt to address various issues that are now part and parcel of building design. Looking back, it truly did anticipate some of the innovative practices that would later be more fully explored by Sullivan, Wright and other modern-era architects—including those who contributed to Mason City’s City National Bank, Park Inn Hotel and the Rock Crest/Rock Glen neighborhood.

GRAMMAR OF ARCHITECTURE

Not everyone praised the Crystal Palace, in part because a lot of the things on exhibit were blatantly wasteful and overwrought. But there were other features that were genuinely functional, thoughtful and educational.

Among these were the Fine Art Courts, consisting of examples of design and architecture from exotic times and cultures, including courts devoted to Nineveh, Egyptian, Alhambra, Medieval, Renaissance, Italian and Pompeian traditions, among others.

The design of these was overseen by Owen Jones, a Welsh architect, who also determined the entire inside arrangement of the Crystal Palace and chose the building’s color scheme.97

Five years after the World’s Fair (by which time the building had reopened at Sydenham), Jones published an elaborate chromo-lithographic book called The Grammar of Ornament, which became a standard source book for historic styles worldwide.98

This book was published in 1856, the year that also marked the birth of Louis Sullivan. It would prove indispensable to architectural training, thanks to its 150 color plates and the persuasive clarity of its text.

With the publication of The Grammar of Ornament, it would be another eleven years before the birth of Frank Lloyd Wright, and a half century in advance of the Wasmuth Portfolio in Berlin.

In Jones’s book, there is an introduction called “General Principles in the Arrangement of Form and Color in Architecture and the Decorative Arts.” It includes thirty-seven design principles or propositions, many of which anticipated the architectural best practices that Wright and others would later promote.99

In his autobiography, Wright recalled having been influenced by Jones’s Grammar of Ornament, a copy of which he initially found in the library of his uncle Jenk’s All Souls Church in Chicago.100

Among the book’s propositions is the recommendation that various visual components (motifs or rhyming attributes), such as certain proportions, colors, textures or angles, should occur repeatedly in a design so that “the whole and each particular part should be a multiple of some simple unit.”101

Throughout his life, Frank Lloyd Wright used a comparable method in his own building designs, which he described as the “grammar” of a building. Most likely, it was Jones’s book that encouraged Wright to use the phrase “the grammar of architecture.”

As Wright later wrote:

Every house worth considering as a work of art must have a grammar of its own. “Grammar,” in this sense, means the same thing in any construction—whether it be of words or of stone or wood. It is the shape-relationship between the various elements that enter into the constitution of the thing. The “grammar” of the house is its manifest articulation of all its parts. …Consistency in grammar is therefore the property—solely—of a well-developed artist-architect.102

Edgar Tafel, who was Wright’s apprentice for almost a decade, recalled how recurrent components were used (“down to the smallest details”) in Wright’s design of the Darwin D. Martin House in Buffalo, New York. “For the Martin house,” wrote Tafel,

Mr. Wright used one kind of brick outside, so he used the same brick on the inside…In keeping with the grammar, the tile of the floor of the exterior porch was the same as the tile on the floor inside. He used only one kind of plaster—sand-floated with integral color. And only one kind of wood: oak. The chairs and the tables were oak and so was all the wood trim. The total feeling of the house was of one stripe, from the overall plan down to the furniture, the door jambs, and the window frames.103

Villa Henny, designed in 1915–19 by Robert Van ’t Hoff, near Utrecht, the Netherlands. Note its resemblance to Prairie School homes. Photograph by Rijksdienst voor Cultureel Erfgoed (Wikimedia Commons).

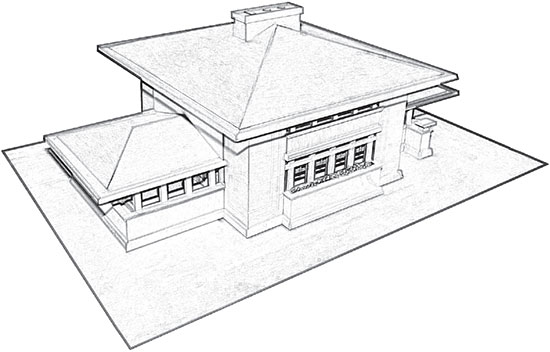

The Stockman House in Mason City, as seen in a model at the Robert E. McCoy Architectural Interpretive Center. Digital drawing from author’s photograph.

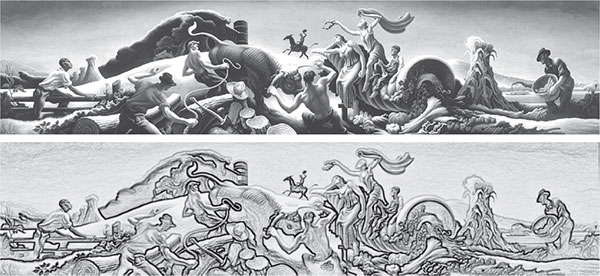

It was Wright’s belief that a comparable grammar is no less critical in works of art (as, for example, in paintings) than it is in building design. He was not alone in that belief, as exemplified by two paintings by midwestern artists Thomas Hart Benton and Grant Wood, whose working years converged with Wright’s. Among their best-known artworks are, respectively, Achelous and Hercules and American Gothic.

HOW FORM FUNCTIONS

When Achelous and Hercules (1947) is viewed not only as a pictorial allegory but also more generally as an arrangement of shapes, sizes, lines, colors, angles and other structural attributes, it is clear that it is built around a rhythmic recurrence of features.

Among its achievements is an informal balance of colors. But there are also intricate shape-based rhymes, two in particular: (1) an oval or elliptical shape (a circle in perspective) and (2) a serpentine or whip-like shape.

Painting by Thomas Hart Benton, Achelous and Hercules (1947). Wikimedia Commons (with author’s diagram).

Painting by Grant Wood, American Gothic (1930). Wikimedia Commons (with author’s diagram).

As is shown by a diagram of that painting, these shapes occur repeatedly, but each time in a new disguise. Sometimes, the serpentine line appears in the form of a rope; the tail of a bull; an axe handle; the tail of a horse in the background; the outstretched arm of a woman, as well as the windblown scarf she holds; the smoke from a steamboat; and so on. The second, elliptical shape can be found in the rim of the bushel basket on the right, the mouth of the horn of plenty, the tops of the severed tree stumps, the brim of the hat in the foreground and so on.

In Grant Wood’s American Gothic (1930), it is equally apparent that a comparable method was used. Wood’s painting is a visual pun, a cartoon-like portrayal of the beliefs and attitudes of midwestern Euro-Americans (among them those who colonized Cerro Gordo County), compared to the houses in which they reside.

The painting’s title might have been We Are What We Live In. The house in the background is typical of a then-prevalent architectural style called Carpenter Gothic. Among its standard features is an upright vertical gesture (derived from the worshipful upward thrust of Gothic cathedrals), abetted by tall, thin windows. These are the same paired verticals that occur famously in the arches of the Brooklyn Bridge, in side-by-side vertical windows and in patterned, stripe-like vertical slats (called board and batten siding) in Gothic-style houses.

In that rich architectural context, the artist has placed in the foreground another pair of uprights: two thin, dutiful Euro-Americans (a farmer and his daughter, according to Wood). Their frontally centered stalwart pose is an intentional echo of the same double U in the three-pronged fork the farmer holds (in a preparatory thumbnail sketch, Wood had initially chosen a rake), the U-shaped stitched motif on the bib of the man’s overalls and, more quietly, the exaggerated facial philtrims (the vertical indentation between the upper lip and nose) to strengthen the side-by-side symmetry of the human face.

In Grant Wood’s paintings, form and content (or form and function, if you will) work in tandem. In American Gothic, the recurrence of that double U reinforces Wood’s portrayal of his subjects’ “righteous” bearing (his term), the rigidity of their strait-laced (corseted) lives and the belief that a God-fearing Euro-American should focus first and foremost on the quest for everlasting, heavenly peace—which they assumed was in the sky.

Like Wood and Benton and their contemporaries, Frank Lloyd Wright had grown up in the shadow of the Gothic Revival (as famously promoted by British art critic John Ruskin and designer William Morris), which was gradually transformed into the arts and crafts movement. He was well acquainted with the enchantment of uplifting gestures (church steeples among them) that might divert parishioners from the ordeals of daily life on earth.

But he was also profoundly committed to transcendentalism and Unitarianism, which emphasized the unity of all things, as well as the omnipresence of God—diffuse and attendant at all times.

EMBRACING THE PRAIRIE

In 1904, when Wright was proposing to design Unity Temple, the church’s leader had assumed that (as with other churches) it would, of course, be crowned by a steeple. In reply to which Wright asked, “Why point to heaven?” Why use the steeple’s “finger” (his term) to misdirect attention away from experiential life on earth?104

A genuine encounter with God, with “God’s countenance,” said Wright, is far more likely to be found in the parishioners of the church themselves.

Like other architects of the same era, Wright made powerful use of uprights, especially in his early career. But as he moved toward the Prairie School phase of his architectural career, he increasingly used exaggerated verticals, not for the overall shape of the house, but instead for interior details (called accents), including elongated ladder-back or tall-back side chairs for dining room furniture or vertical stripe-like patterns of wood in interior trim and elsewhere.

Two panoramic photographs of the flat midwestern prairie (circa 1910). LOC Prints and Photographs.

As is widely known, Wright was increasingly drawn to the extraordinary flatness of the midwestern prairie—“the gently rolling or level prairies of our great Middle West,” he said, “where every detail of elevation becomes exaggerated.”105

At the same time, he did not completely abandon the Gothic upright; instead, he turned it on its side so that it embraced the prairie instead of reaching for the sky. As often as not, that expansive wing-spread form became a cantilevered plane, as in the ledge-like concrete slabs of his design for Fallingwater.

As Wright scholar Donald Hoffmann said, “Wright effectively turned the Gothic on end. His horizontal rhythms told the truth of things by expressing the repose of masses in harmony with gravity and the landscape; his architecture spoke of life here and now, not the kingdom of a Christian heaven.”106

QUEST FOR OIL

As noted earlier, the community that would become known as Mason City, Iowa, was established in 1853. By coincidence, it was in that very same year that another primary influence in Wright’s life also took place (still more than a decade before he was born).

That critical event occurred more than ninety thousand miles west of Mason City in the harbor of Tokyo, Japan, where a half century later Wright would be commissioned to design the Imperial Hotel.

What happened in Tokyo Bay in 1853 had everything to do with the Industrial Revolution—as well as with the eventual growth of Cerro Gordo County and Mason City. Three years earlier, California had achieved statehood, which enabled the U.S. government to set up West Coast shipping ports. This set the stage for permanent trade relationships with Pacific nations, while relying less on American ports on the East Coast.107

Not surprisingly, all this was related to oil—not petroleum but whale oil. Whale oil was highly valued at the time for its use in machine lubrication, soap and margarine, as well as a lantern fuel. Also of value was whale bone, the uses of which (in corsets, collar stays, eyeglass frames and other products) foretold the need for plastics.

Unfortunately, whales had been hunted in excess off the coast of New England (remember Melville’s Moby Dick), creating an urgent need for new whale-hunting options in the Pacific, combined with other resources.

To complicate matters, there was a critical problem because Japan’s shipping ports had been tightly closed to foreigners (even diplomatic envoys) since the 1630s.

But in 1853, U.S. commodore Matthew Perry sailed abruptly into Tokyo Bay with four heavily armed steamships and (threatening to attack) delivered a letter from President Millard Fillmore, demanding trade negotiations. Perry then departed but returned early the following year, with twice the number of armed, ominous black ships. This time, Japan agreed to open its ports.

In subsequent years, the consequences not only benefited Japanese and Western commerce but also led to a frenzy of interest among Europeans and Americans in Japanese cultural artifacts (prints, ceramics, furniture, clothing, fans and so on). For the rest of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth, Westerners all but went berserk in a strange collecting frenzy for traditional Japanese products.

This whirlwind phenomenon, which the French called Japonisme, was affiliated with art styles like impressionism, the aesthetic movement, art nouveau (derived from the name of a gallery in Paris, owned by Siegfried Bing, where imported Japanese items were exhibited and sold) and the arts and crafts movement.108

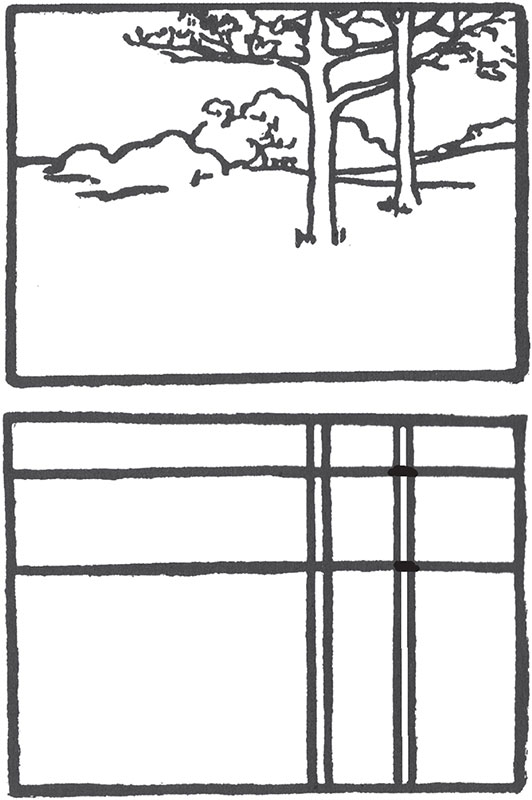

The widest assortment of Western artists, designers and architects was captivated by the quaintness and startling simplicity of Japanese artifacts. They were especially interested in a category of woodblock prints known as Ukiyo-e, or “Pictures of the Floating World” (a euphemism for the red-light district).

Those influenced by these prints included James A.M. Whistler, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Mary Cassatt, Pierre Bonnard, Édouard Manet, Paul Gauguin, Claude Monet, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Edvard Munch and Alphonse Mucha, to name a few.

An especially avid enthusiast was Vincent Van Gogh, who made interpretations of some of the Ukiyo-e prints as oil paintings or showed them hanging on the walls in the backgrounds of his paintings of room interiors. In a letter in 1888, Van Gogh told his brother that “all my work is in a way founded on Japanese art…”109

But there were other consequences as well, among them Whistler’s The Peacock Room, Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado and the exotic illustrations of Aubrey Beardsley.

JAPANESE PRINTS

In the meantime, Western familiarity with Japanese artifacts was greatly accelerated by their inclusion in international trade exhibitions, including those in London in 1862 and in Paris in 1867 and 1878. Japanese prints were also shown at the 1876 Centennial International Exhibition in Philadelphia, where other innovations were the Remington typewriter, Shaker furniture, Hires root beer, Heinz ketchup, Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone, bananas, popcorn and even kudzu (to counter soil erosion).

As mentioned earlier, it was the same exposition that included a kindergarten demonstration, which Frank Lloyd Wright’s mother attended and which prompted her to buy a set of Froebel blocks for her preteen son, the aspiring architect. This is noteworthy because young Frank would soon become a major collector, dealer and curator of Ukiyo-e prints.

It is important to reiterate that whenever Wright was asked what had influenced his development as an architect, he invariably cited two factors. One was his childhood introduction to Froebel’s kindergarten blocks, and the other was his long-term interest in Japanese prints.

In his autobiography, Wright said that “if Japanese prints were to be deducted from my education, I don’t know what direction the whole might have taken.”110

And in an address to his apprentices in 1957, he recalled that when he saw Japanese prints for the first time, “and I saw the elimination of the insignificant and simplicity of vision, together with the sense of rhythm and the importance of design, I began to see nature in a totally different way.”111

So what was it about Ukiyo-e woodblock prints that made them so enchanting to Wright, as well as to so many others in art, architecture and design?

There are many ways to answer that (all of them both interesting and complex), but of particular relevance here is that these prints were made in accordance with an underlying structural plan comprising geometric shapes. It may help to think back to the earlier examples of the paintings of Benton and Wood, both of whom were well aware of Ukiyo-e woodblock prints.

One of the first to talk about this was an American artist, author and art educator named Arthur Wesley Dow. One of Dow’s followers, Alon Bement, was an important teacher for Georgia O’Keeffe, while another, Ernest Batchelder, was Grant Wood’s design instructor. In 1899, Dow published an influential book titled Composition: A Series of Exercises in Art Structure for the Use of Students and Teachers. It went through many editions, and although the text is outdated now, it remains in print today.112

COMPOSITIONAL FRAMEWORK

Kakuzo Okakura, a Japanese scholar who was Dow’s friend and Asian counterpart (and the author of a famous book called The Book of Tea) referred to these structural lines as “bones,” in the sense of framework or skeletal plans.113

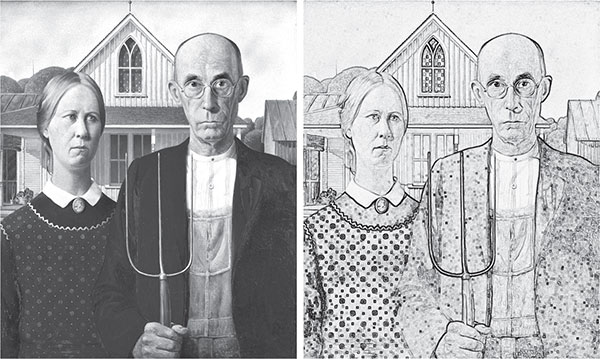

But Dow himself preferred the phrase “line ideas.” To him, they were equally fundamental in art, architecture and design.

Each [whether artist or designer] has before him [when he starts] a blank space on which he sketches out the main lines of his composition. This may be called his line-idea, and on it hinges the excellence of the whole…A picture, then, may be said to be in its beginning actually a pattern of lines.114

In Dow’s book, he illustrates this concept with side-by-side illustrations, in the first of which two vertical trees are represented, with other features in the background, positioned horizontally.

Drawing and diagram from Arthur Wesley Dow’s Composition (1899), showing the underlying line idea in a drawing of two trees.

Comparable analyses of three woodblock prints by Ando Hiroshige. LOC Prints and Photographs (with author’s diagrams).

The second is a diagram (the initial line idea) of the underlying structure for the same composition, composed of “an arrangement of rectangular spaces much like the gingham [or tartan or plaid] and other simple patterns.”115

While Dow may have coined the term “line idea,” he was not the first to use underlying structural plans in art and design compositions. Equivalent methods had been used for centuries, and today (because of our use of computers), they are used more widely than ever before.

They are no longer known as line ideas but are instead referred to as “grid lines” or “layout grids.” For example, nearly every publication today (books, magazines, newspapers, brochures, posters and websites) is based on an invisible network of lines (of which most readers are unaware), in part because virtually all publication design software provides default layout grids, which can either be activated or turned off.

Why are grid lines widely used? Simply, it is because of how our brains are built: as proposed by gestalt psychologists and confirmed by current neuroscience, we have an inherent tendency (a perceptual default) to see as belonging together shapes that are lined up in space, sometimes called “edge alignment.”

That’s why rows and columns in a marching band appear to move together as one. That’s why we indent for paragraph breaks. Simply, these are reliably powerful ways to make a composition appear orderly (whether page designs or building plans)—to make it easier to navigate.116

Reproduced here are diagrams of two well-known paintings from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. One, titled Arrangement in Gray and Black No. 1: The Artist’s Mother (1871–72), is by American expatriate artist James A.M. Whistler; the other, called Portrait of Fritza Riedler (1906), is by Vienna secessionist painter Gustav Klimt.

Both artists were strongly influenced by Japanese prints. Whistler was about thirty years older than Klimt, and there is nearly the same span of time between the completion of their two paintings. The artists were well acquainted, and Klimt admired Whistler’s work. Surely, it is not a mere coincidence that the two paintings have such similar layouts. More than likely, Klimt’s painting was a tacit, deliberate tribute to Whistler.

Like artists and graphic designers, architects have often used edge alignment to make distinct components appear to connect. In addition, they have also lined up focal points in a method that architect Le Corbusier called “regulating lines.”117

Arrangement in Gray and Black No. 1: The Artist’s Mother (1871–72) by James A.M. Whistler. Wikimedia Commons (with author’s diagram).

Portrait of Fritza Riedler (1906) by Gustav Klimt. Wikimedia Commons (with author’s diagram).

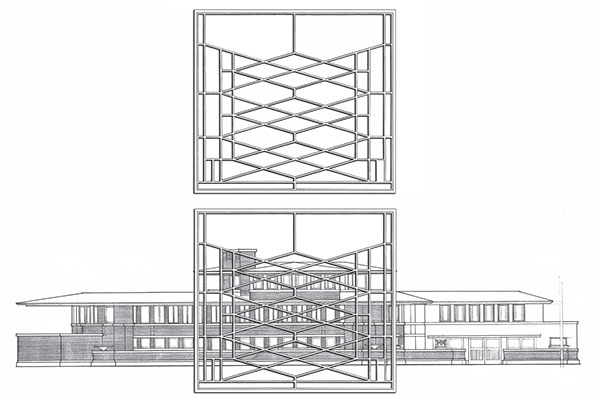

Comparison of art glass window and building design for the Robie House, as proposed by Jonathan Hale. Historic American Buildings Survey, LOC Prints and Photographs (with author’s diagram).

There is a vivid discussion of this in The Old Way of Seeing by architect Jonathan Hale. “The most common type of regulating line,” he writes, “is a diagonal connecting key points on a rectangle…but they can [also] be circles or semicircles.”118

Of the visual examples cited by Hale, perhaps the most astonishing is an architectural drawing of the south elevation of the Robie House by Frank Lloyd Wright, juxtaposed for comparison with an art glass window from the same building.119 As our own revision of that diagram shows, the grammar in the window’s line idea is echoed by the pattern in the profile of the building.

INDEBTEDNESS TO JAPANESE

The origin of this kind of grammar may be, as Wright himself explained,

some plant form that has appealed to me, as certain properties in line and form of the sumac were used in the Lawrence house at Springfield; but in every case the motif is adhered to throughout so that…each building aesthetically is cut from one piece of goods and consistently hangs together with an integrity impossible otherwise.120

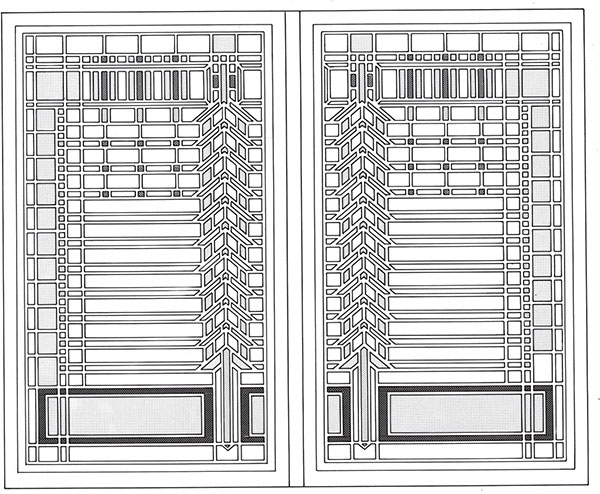

In comparing Dow’s line ideas with diagrams of woodblock prints, it is obvious that all of these might readily have functioned as plans for art glass windows—especially when abstracted to the degree of those designed by Wright.

As David Hanks has noted, plant-based motifs are commonly found in the work of other turn-of-the-century designers, but “none carried the designs to the extreme geometric abstraction or the ‘essence of the plant’ that Wright did in his art glass.”121

Or, as Joseph Masheck writes, some of Dow’s line idea diagrams “compare respectably with such productions…as stained-glass windows…by Frank Lloyd Wright.”122

It is plausible that Dow’s influence on Wright’s architectural compositions may have been more direct than that. In 1893, Dow had been appointed a curator of the Japanese art collection at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, where he was strongly influenced by an eminent Asian scholar, Ernest Fenollosa, who was the head curator of the same collection. Fenollosa’s mother was Mary Silsbee, and his first cousin was a Chicago-based architect named Joseph Lyman Silsbee.123

Examples of Wright’s art glass window designs for the Darwin Martin House. Historic American Buildings Survey, LOC Prints and Photographs.

Interestingly, in 1886, it was Silsbee who was hired to design a chapel (called Unity Chapel) near Spring Green for none other than the Lloyd Jones family, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Unitarian clan. That same year, Wright dropped out of the University of Wisconsin and joined the staff of Silsbee’s firm. In that office, he was surely introduced to Ukiyo-e woodblock prints (given by Fenollosa to Silsbee, his cousin) and may have begun his own collection in 1890.124

As historian Kevin Nute has persuasively shown, it is likely that some of Dow’s line ideas—whether consciously or not—were initial inspirations for the floor plans of some of Wright’s residential designs.125 It is also suggested that Wright was influenced by Japanese architecture (not just Ukiyo-e prints), despite his repeated denials.

In that regard, he was especially offended when his friend Charles Ashbee, the British Arts and Crafts designer, stated (and refused to edit out) in the introduction to the second volume of the Wasmuth Portfolio that there was a “very clear” Japanese influence in Wright’s architecture. “He is obviously trying to adapt Japanese forms to the United States,” Ashbee continued, “even though the artist denies it and the influence must be unconscious.”126

To that statement, Wright replied (in a letter to Ashbee), “Do not accuse me of trying to ‘adapt Japanese forms’…I admit [being influenced] but claim to have digested it.”127 As for the sometime resemblance between Japanese buildings and his own, it was simply “confirmation” of the universal rightness of the forms that he himself had created—wholly independently.

In 1957, in one of Wright’s last repudiations of influence, he emphatically asserted that there was never any outside influence on his architecture.

He did note three exceptions, conceding that he had been influenced by Louis Sullivan, Sullivan’s business partner Dankmar Adler and John Roebling, designer of the Brooklyn Bridge.

“My work,” Wright went on to say, “is original not only in fact but in spiritual fiber. No practice of any European architect to this day has influenced mine in the least,” and as for “the Incas, the Mayans, even the Japanese—all were to me but splendid confirmation [of my own original genius].”128

Despite such staunch denials (a small dog with a nasty bark, Wright’s protests were outsized), however original one might be, no mind is an island in terms of the mix of contributing ingredients in the creative process.

What distinguished Wright from others was not an immunity from influence. It was instead the ease with which his imaginative powers sought out, realized the potential of and adapted for his purposes the richest, most disparate menu of influences—which, apparently, he could not admit.

To name just a handful of factors, throughout his long, productive life, he embraced and made prolific use of the finest characteristics of his Welsh ancestry, transcendentalism, Unitarianism, Beethoven, Bach, Japonisme, nature, kindergarten, industrialization, the arts and crafts tradition, Louis Sullivan, streamlined automobiles and proto-modern building design.

INDUSTRIAL SURGE

As for the rural community of Mason City, it, too, was never an island. Like Wright, it was inevitably swayed by the widest range of circumstances—from municipal to national to worldwide—in terms of how and when it thrived.

The city’s access to the river provided an ample supply of fresh water, a ready convenience of transport and occasions to make industrial use of water power.

The city’s first sawmill was constructed on the Winnebago River in 1855, followed in 1870 by a flour mill, called Parker’s Mill. Located on Willow Creek, adjacent to land that would later become Rock Crest/ Rock Glen, the latter’s big stone wheel could make eighty barrels of wheat flour per day.129

Soon, a second mill sprang up, and the success of these and other enterprises, spurred by the arrival of five railroad lines, enabled a boom in industrial growth. Soon, there was a lumber yard, a physician, a post office, a grocery store, a blacksmith shop, barbershops, a newspaper, a public library, a photographer, lawyers, banks and bankers, a movie theater, opera houses, churches and schools. In 1870, the population of Mason City was 1,183. Ten years later, it had more than doubled to 2,510, and by 1920, it had reached the then phenomenal total of more than 20,000.130 As the city’s population swelled, the need for building construction increased. While trees were sometimes plentiful in areas next to the rivers, they were typically in short supply on the open prairies. High-quality, durable lumber, required for lasting construction, usually had to be shipped in.

The prospects for building construction improved in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, when it was determined that, west and south of Mason City, there were massive underground reserves of blue and yellow clay, sometimes as deep as forty feet.

This resource was a godsend, since the clay was ideally suited for the manufacture of bricks for building construction, for making cement and for producing drainage tiles that farmers so desperately needed to ensure reliable yields from their crops.

By 1882, a single Mason City firm was producing 400,000 bricks per year. Ten years later saw the founding of the Mason City Brick and Tile Company, followed not long after by a multitude of other plants, especially those for brick and tile.

By 1912, the year when actual construction began on the Rock Crest/Rock Glen neighborhood, Mason City was manufacturing “more brick and tile and more Portland Cement than any city of any size in the world.”131

The eventual role that the city would play in the cement industry was contingent on the presence of large deposits of limestone (like those that form the limestone bluffs in the Rock Crest/Rock Glen vicinity).

Clay and limestone can be mixed to make a material called Portland cement. Developed in the early nineteenth century and refined by mid-century, it was referred to as “Portland” simply because its initial white-gray color resembled that of Portland stone, a limestone that is quarried on the Isle of Portland, in Dorset, England.

Vintage postcard of the Northwestern States Portland Cement Company in Mason City. Author’s collection.

Advertisement for Wright’s concrete fireproof house in a 1907 issue of the Ladies’ Home Journal.

By 1908, Mason City had become the location of the Northwestern States Portland Cement Company, whose success soon after brought to town a branch of a competing firm, the Lehigh Portland Cement Company of Pennsylvania.132

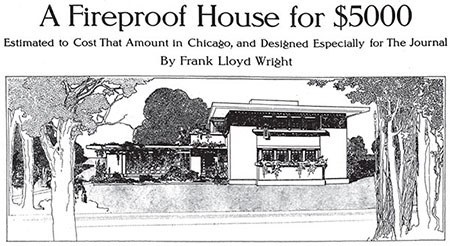

The prominence of Mason City in relation to the production of Portland cement is of additional interest because Frank Lloyd Wright was an early contributor to its use in building construction.133

As early as 1901, he had designed a pavilion for the Universal Portland Cement Company at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo. Nine years later, in December 1910, soon after returning from Europe, his first public commission was a pavilion exhibition in New York for the Cement Show, an event that hoped to demonstrate the advantages of building houses with concrete.134

Such houses were, for one thing, fireproof—a virtue Wright had emphasized in the house plan he had published in the Ladies’ Home Journal. It was also resistant to dampness, and as Wright’s later buildings showed, the range of shapes it could take on were all but unlimited. Concrete was also less costly than certain other materials, as Wright had proven earlier in his 1907 design for the Unity Temple in Oak Park.

AGRICULTURAL GROWTH

When agriculture is mentioned, among the things that come to mind are animals raised for consumption, such as cattle, hogs, sheep and chickens. Consistent with that, in the history of Mason City, a leading industrial component became what is euphemistically called “meatpacking.” It includes the rote and unpleasant procedures by which farm animals are slaughtered, processed, cleaned and packaged for distribution as food, along with a wide range of byproducts.135

Assembly line slaughterhouses (mainly for hogs and cattle) had flourished in Cincinnati (known then as Porkopolis) since the early nineteenth century and rapidly spread to Chicago. Henry Ford supposedly said that the automobile “assembly” line occurred to him by watching the step-by-step killing and “dis-assembly” of hogs in a pork-producing plant.

Meatpacking was made especially viable by the profusion of railroad lines, as well as by provisions for refrigerated storage and transportation. The first meatpacking plant in Mason City was established in the mid-1890s. Subsequently purchased by Jacob Decker, its yearly production soon increased to ten times what it had been before.136 In 1930, it was purchased by Chicago’s Armour Packing Company and became the largest source of jobs in Mason City.

Other agricultural products that come to mind are the area’s major farm crops, such as corn, soybeans, hay and oats. In addition, it may be surprising to learn that, for many years, Mason City was an industrial hub for the production of beet sugar, a crop that grew out of a curious past.

In the United States, beet sugar was initially made by New England abolitionists (some of whom were no doubt transcendentalists), who campaigned to boycott the use of West Indies cane sugar, which was harvested by slaves.

In 1917, the Northern Beet Sugar Company established a major processing plant in Mason City, a facility described back then as “one of the most efficient beet sugar factories in the world.”137

The city was chosen, the article said, because it is

in the heart of one of the finest agricultural sections of the country. It has five railroads leading into it, thus affording ample transportation facilities for the movement of beets from the surrounding growing districts to the factory and for the distribution of the high grade granulated sugar which the factory will produce.138

Industrialization brought low-paying employment for Mason City workers, but it also brought cultural amenities, such as the Parker Opera House. Photograph by Dan Breyfogle (Wikimedia Commons).

Another advantage, the article adds, is that “a large supply of limestone is on the site, thus eliminating the need of importing this most essential material for sugar production,” not to mention the virtue of having “an abundance of pure water.”

Among the company’s personnel was a chemist named William M. Baird (the father of puppeteer and entertainer Bil Baird, who grew up in Mason City), who was described when he died in 1933 as “the man who designed and built the Mason City sugar factory and who for 40 years was a prominent figure in the beet sugar industry in the middle west.”139

The steady increase in local employment opportunities, the bulk of which were low-paying and sometimes hazardous jobs, attracted a flood of newcomers. In the years between 1910 and 1926, according to Robert McCoy, “Mason City had the highest growth rate [of any city] in Iowa and the third highest proportion of ‘new immigrants’ in the state.”140 Of the newest arrivals in those years, a significant number were of Greek origin, as well as Eastern Europeans, thus enriching the cultural fabric.

Beyond the reach of the city itself, what had once been tall-grass prairie increasingly became transformed into vast stretches of cultivated farmland—and more so today than ever before. As one century was shape-shifting seamlessly into the next, industrialization had taken command, and modern design had come with it.141

In the years that led up to World War I—which tragically could be described as industrialization applied to the slaughter of our own species—a fortuitous set of conditions prevailed that prompted a once-remote region (a “microcosm of America’s industrial and westward expansion,” to quote McCoy) to decide to construct, to underwrite financially and to savor the cultural benefits of a radically new architectural style—Prairie School—a style that mirrored the city’s surroundings.142