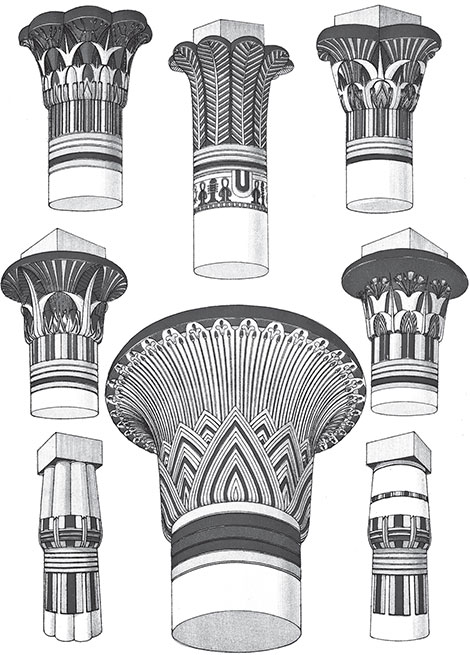

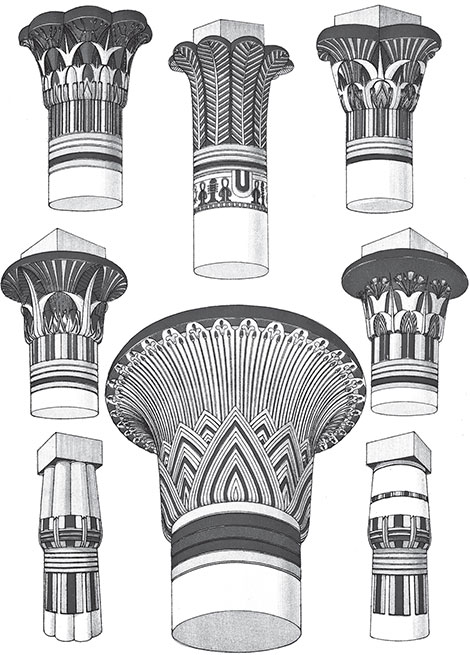

Lithographic plate from The Grammar of Ornament (1856) by Owen Jones, an indispensable sourcebook for architects.

3

CITY NATIONAL BANK AND PARK INN HOTEL

In 1911, in an editorial in the November issue of the Western Architect,negative observations were made about Frank Lloyd Wright as a residential architect. The article referred to one of his house designs as “practically a freak,” then added that no other architect has “failed so signally in the production of livable houses.”143

For unknown reasons (maybe a stream of subscribers’ complaints), the magazine’s very next issue made an odd turnabout. Instead of denouncing Wright’s architecture, its opening article was a five-page feature about one of his recent building projects, located in Mason City, Iowa—albeit a bank, not a livable house.144

WRIGHT’S BANK AND HOTEL

The project played up in the magazine was, of course, the City National Bank and Park Inn Hotel. As eight photographs in the article show (although the text dwells almost exclusively on the bank), it was essentially two buildings whose functions far exceeded those of a bank and a hotel.

The tandem City National Bank and Park Inn would in time be lauded as a pivotal achievement in Wright’s career. He designed only six hotels in his life (only five of those were actually built), all of which were created between 1908 and 1923, the Park Inn being the second and the only one that still survives.

Lithographic plate from The Grammar of Ornament (1856) by Owen Jones, an indispensable sourcebook for architects.

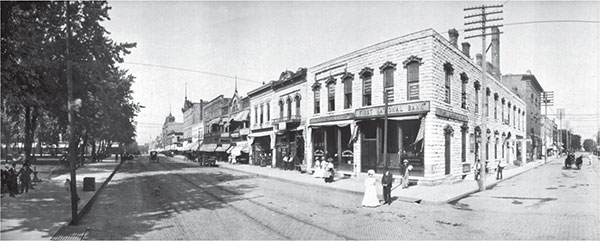

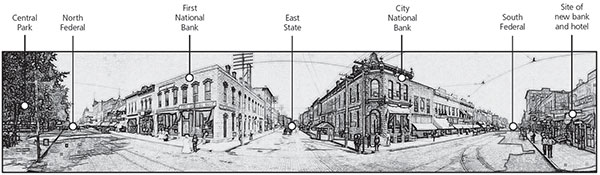

Left half of a panoramic photograph of downtown Mason City in 1907. Photograph by Frederick J. Bandholtz. LOC Prints and Photographs.

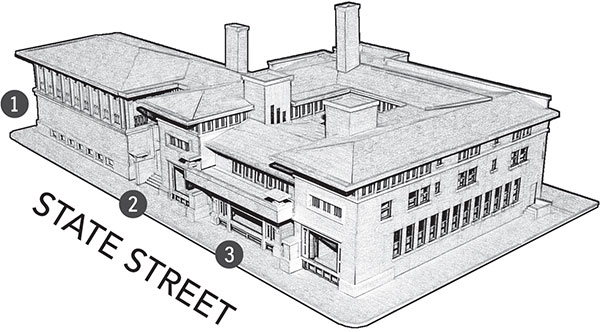

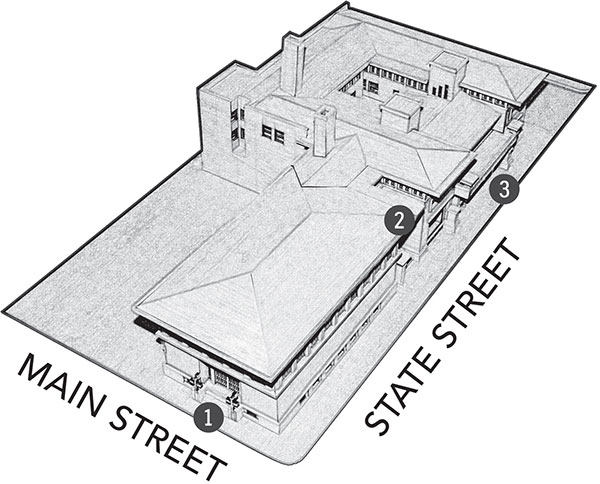

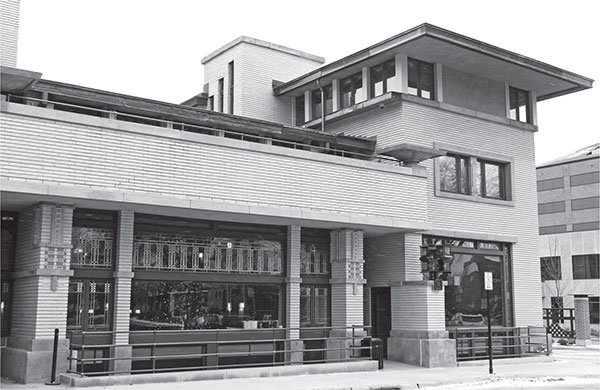

Structurally, Wright designed the two buildings to function as non-identical twins, distinct yet inseparable entities that are linked by a shared transitional zone, a generic first-floor entrance that is now known as the “central waist.”

The buildings were commissioned by the board of directors of the long-established City National Bank, which had been founded initially in 1884 as the City Bank. The original Italianate building for that facility (still standing and itself restored, it is now a clothing store) was located at 1 South Main Street, directly east and across the street from the eventual location of the new bank building of the same name.145

In order to plan the new building, Wright traveled to Mason City, most likely by train, from Chicago. No one seems to know for sure how many times he visited, but one news story at the time claims that he was “frequently” in town. According to another source, when he did visit, he stayed at the Markley home.146

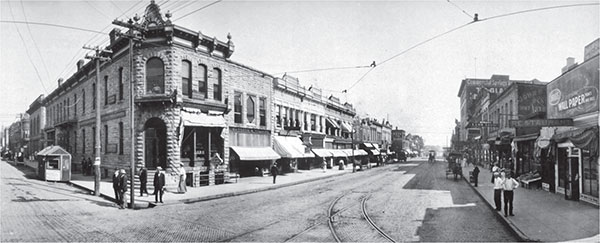

These visits apparently happened in 1907–08, at which time he studied the bank’s proposed construction site, which could easily be observed from the intersection of the two major downtown streets, Main Street (renamed Federal Avenue in 1916), a major north–south city street that cuts through the business center, and State Street, which spans the city east–west. At the time of Wright’s visits, Main Street was the city’s busiest thoroughfare. By comparison, State Street was less congested, quieter and more subdued, in part because it is the edge of a square-block public park.

Right half of the same panoramic photograph, looking south on Main Street. Photograph by Frederick J. Bandholtz. LOC Prints and Photographs.

Digital drawing of the same view of Mason City in 1907, as photographed at the intersection of Main Street (Federal) and State. Author’s diagram.

All of this was substantially changed as recently as 1985, when, in the hope of revitalization, several north–south blocks were closed and replaced by a downtown shopping mall. The traffic route that had formerly been Federal Avenue was split and then diverted to separate parallel byways, named Washington and Delaware Avenues. Those two-pronged one-way streets now serve as Highway 65.

CENTRAL PARK

Set aside for community use in 1855, the city’s so-called Central Park was (and is) a refuge for park bench relaxation, a convenient location for public events, as well as a place to reflect on aspects of the city’s past.147

The park’s most conspicuous feature then (and to a lesser extent today) is a tall monument, erected in 1883, in memory of Cerro Gordo County citizens who perished in the Civil War. It is also a fitting reminder that no other state in the Union, proportionate to its population, contributed more soldiers to that devastating conflict than did Iowa. Nearly half of all males in Iowa served in the Civil War; thirteen thousand of them died in battle, from disease, in POW camps or due to other circumstances.148

If Mason City’s Central Park is at all familiar, it may be for good reason. This same Iowa community was the boyhood home of American composer and playwright Meredith Willson.

Willson was the author of several well-known Broadway musicals, of which the most unforgettable is The Music Man, which was later made into a popular film. The setting for the story is a fictional Iowa community called River City, aspects of which were heavily based on Willson’s childhood experiences in Mason City.149

As a result, in the community’s tourist promotions, the name Mason City is used interchangeably with its Broadway (and Hollywood) nickname: River City.

In a poignant moment in Willson’s film, the main character (a music professor and con man named Harold Hill) speaks to a gathering of gullible townspeople at the base of a statue in a tranquil public park. “Yuh got trouble,” Hill warns the city’s impressionable citizens, “right here in River City.”150 The park in the film is a caricature of Mason City’s Central Park.

Each year, Mason City celebrates the achievements of Willson, the city’s undisputed favorite son. The composer’s birthplace is a house museum on South Pennsylvania Avenue, where it stands beside a multimedia complex for tourists called Music Man Square, which includes a movie set streetscape of the musical’s mythical city, the Meredith Willson Museum, a banquet center and various music-themed facilities.151

Aside from Meredith Willson’s celebrity, and the city’s increasing distinction as a historic architectural site, its other well-known claim to fame is its proximity to the Surf Ballroom (west of the city in Clear Lake) and the Mason City airport, where rock-and-roll musicians Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens and J.P. (the Big Bopper) Richardson perished in an airplane crash in 1959.152

Other accomplished Americans were born, grew up, resided or died in Mason City. Among them were puppeteer Bil Baird, who created the marionettes for the film version of The Sound of Music; Merle Armitage, a celebrated book designer, art director and theater impresario, mentioned earlier; Carrie Chapman Catt, a famous women’s suffrage advocate; and U.S. Army general Hanford (Jack) MacNider, assistant secretary of war and ambassador to Canada.

General MacNider was the son of Mason City businessman Charles H. MacNider, for whom the city’s MacNider Art Museum is named and who successfully took over management of the Northwestern States Portland Cement Company, the lucrative building materials firm that was founded by his father.153

Charles H. MacNider was also a prominent banker who built a large, six-story structure for the First National Bank in 1910 (in part as a business rivalry with the City National Bank), replacing its earlier building. MacNider’s bank would soon become the largest in the state.

MacNider was a powerful, well-connected political foe of the directors of the City National Bank, and the construction of his new high-rise bank was timed in part to coincide with the completion of the three-story building that Wright had been commissioned to build. MacNider’s new First National Bank was at that same intersection of Federal and State, facing the park, cater-corner across the street from its then competitor.154

A colorful, if now mostly amusing, event in Mason City history was the robbery of the First National Bank on March 13, 1934, by gangsters John Dillinger, Baby Face Nelson and five others, who were equipped with Thompson submachine guns (referred to then as “Tommy guns”).

The Mason City police, armed only with .38-caliber handguns (and certainly not amused at the time), watched helplessly from sheltered posts behind large rocks in downtown Central Park. The bank robbers scored $52,000 that afternoon, before successfully speeding away with a carload of hostages.155

MEDIATING DIFFERENCES

As for the City National Bank and Park Inn, it was a formidable challenge for Wright to design a three-story building in which the primary functions were both those of a bank and a hotel. And if that were not enough, he was also required to include additional suitable spaces for a law firm (Blythe, Markley, Rule and Smith), rental spaces and retail shops.

In the end, Wright’s way of addressing the problem was at once shrewd and resourceful. He positioned the bank in such a way that its imposing, fortress-like entrance opened onto Main Street (now Federal Avenue), where high-powered business exchanges took place. In contrast, the front entrance of the hotel bordered on State Street, where it faced the tranquil downtown park. As a result, the City National Bank and Main Street were mutually suitable in temperament, as were the Park Inn and Central Park.

There is a muted resemblance between Wright’s architectural solution and Friedrich Froebel’s second kindergarten gift (the educator’s favorite), consisting of a wooden sphere, a cube and a cylinder. As discussed earlier, Froebel had provided a mediation between the two opposing shapes of the sphere and the cube (thesis and antithesis) by bridging them with the transitional form of the cylinder (synthesis), which shares attributes with both.156 Not surprisingly, Froebel was strongly influenced by German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel.

In Wright’s design for the combined bank and hotel, he may have thought in a similar way: he placed the bank at one end, facing east, with the Park Inn at the opposite end, looking north toward Central Park. He reconciled the different halves by joining them with the transitional waist (Wright’s equivalent to the cylinder), which served to soften the difference between the needs and functions of the bank as distinct from those of the hotel.

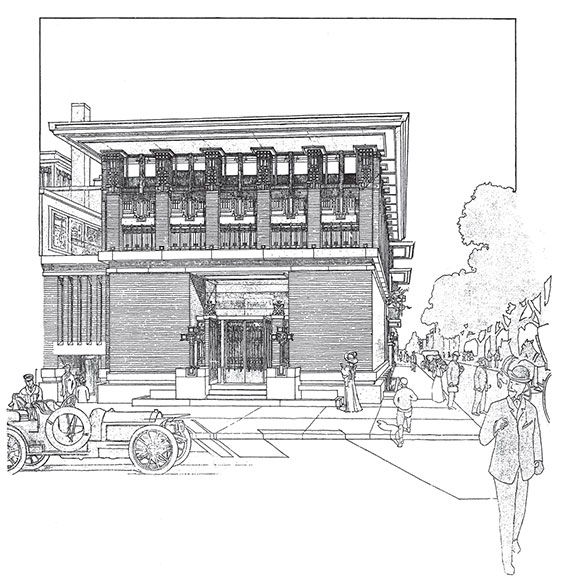

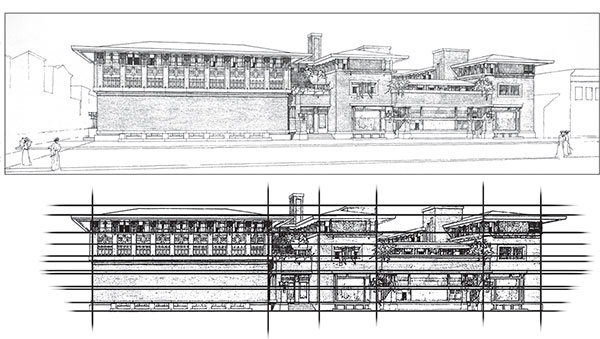

Drawing of the entrance to the City National Bank provided to the clients by Wright’s studio, as reproduced in the Wasmuth Portfolio.

The waist, at the same time, was a pragmatically functional feature, since it allowed for separate access to the law firm, rental offices and retail shops. It had been the clients’ intention that the entrance to the waist would be the building’s primary door to the street.

But of course, there was more to Wright’s design than simply that. He also implanted connections between the two buildings by setting up a web of rhymes.

Model of the City National Bank and Park Inn as of 1910. The hotel (1) is in the foreground; the bank entrance (not visible) is at the upper left (1), while the transitional waist is at (2) and the Park Inn entrance is at (3). Diagram from author’s photograph.

The same model as viewed from the northeast, with the same numbering system. Both renderings are based on a model exhibited at the McCoy Architectural Interpretive Center. Diagram from author’s photograph.

Wright’s elevation drawing of the north face of the bank and hotel (from the Wasmuth Portfolio) and (below that) a diagram of the buildings’ line ideas. Public domain with author’s diagram.

Wright frequently strengthened horizontal lines by using lighter colors of mortar in the vertical gaps between the bricks. Author’s diagram.

He accomplished this in various ways: by aligning the overhanging roofs; by matching the heights and proportions of various key components; by repeating the widths and thicknesses of horizontal concrete bands; by the continuity of color (including, on the upper floors, colored terra-cotta tiles); by the selective positioning of abstract art glass windows; and by the repeated use of the same building materials (especially brick, concrete and glass).

Looking closely at a profile of the two buildings from across the street in Central Park, one can imagine how Arthur Wesley Dow might have sketched out the layout scheme (recalling the line ideas he found in Ukiyo-e woodblock prints) that tacitly contributes to the unity of the two buildings while also maintaining the gesture of the outreach of the prairie.

In addition, as he often did in brick buildings, Wright underscored the horizontality of both buildings by the use of what bricklayers call raked horizontal mortar joints combined with flush-pointed vertical joints.157 He amplified this by using two different colors of mortar, in which the vertical gaps between two bricks are filled with a brick-matching mortar, while the horizontal spaces are filled with a contrasting color of mortar that stands out and supports the illusion of lateral lines.

LARGE-SCALE STRONG BOX

It turns out that the text in the Western Architect article was written by Wright himself. It had been published initially in the Mason City Times (November 5, 1910) under the headline “City National Bank Moves to Its New Home.” A note that accompanies the article states that it was “prepared for this newspaper by the architect Frank Lloyd Wright.”

In the Western Architect, the article starts by revealing that the bank’s design is based on the assumption that “a bank building is itself a strong box on a large scale; a well aired and lighted fireproof vault.”158

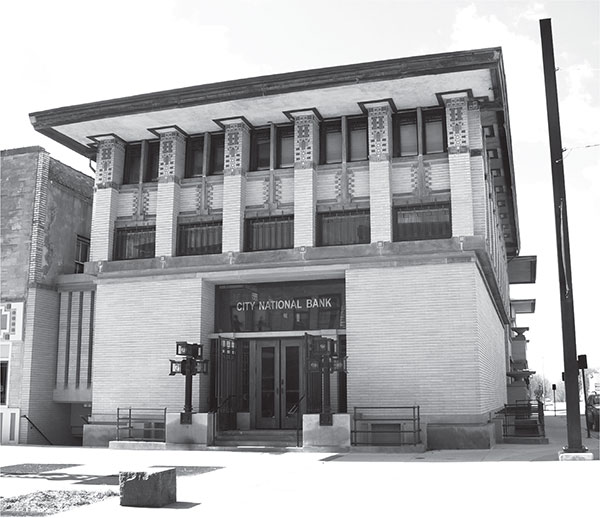

And indeed, when viewed in profile from the park, the bank component looks unquestionably solid and stable. Its massive walls appear to form an impenetrable stone fortress, with no openings and no access to the outside except through the ominous ceremonial front entrance (both elevated and recessed).

One problem, of course, is that a vault-like box with solid walls does not allow for much lighting. In addition, how can an architect ensure the compatibility of a large-scale strong box with a markedly different topmost floor of inviting, well-lit offices?

In addressing the issue of lighting, Wright made use of a spatial illusion. At the top of the massive expanse of the outside wall, he caps what first appears to be the ceiling of the first floor with a ledge-like horizontal band or belt, a feature that strongly echoes a gravity-grounded concrete band at the base of the building’s foundation.

Photograph of the exterior of the City National Bank shortly after its completion (circa 1910). Mason City Public Library.

What is disarming (as well as delightful) from the outside is that the row of windows that begin at the top of that ledge-like concrete band are not really a second floor at all (it is architectural sleight of hand). Instead, those windows extend the bank’s ceiling inside, making the ground floor two stories tall, while the row of windows at the top provide both ventilation and light.

Only above that deceptive ceiling does the floor of the rental offices start, which themselves are cheerfully lighted by a plentiful border of art glass windows. In the article, Wright describes these windows as a “richly varied frieze” that animates the topmost “crown.”159

Viewed from the street, this creates the impression of a structure of two equal layers. That effect is reinforced in the upper half by a sequence of thirty-two brick pillars—six of which run across the front and rear, with ten each spaced along the sides. Because of those square-shaped pillars (or columns), the top half of the building appears to be just as substantial as the half below.

In the end, the building’s bottom portion (the so-called strong box) appears to be reassuringly thick, as one would expect of the walls of a bank, yet the top is conspicuously playful because of its colorful art glass windows and ornate interplay of tiles.

INSIDE AND OUT

Understandably (for security reasons, if nothing else) there is not a profusion of photographs of the bank’s interior. The architect’s floor plans have survived (there are at least two different versions), but there are few other records of the bank interior that predate 1926.

Among the surviving photographs (not reproduced here) are those that Wright included in his 1911 article in the Western Architect.160 These show the bank’s interior as if the viewer had stepped inside. The horizontal brick motif that is on the exterior walls is continued on the inside. In the center, there is a gated customer service zone that bears the same design treatment, with three bank teller windows.161

There are also photographs of the bank’s ornate, imposing vault. It is in the center, behind the tellers’ island, in a separate fireproof, brick-lined room. Its arched entrance wall looks like the hearth in a Wrightian home.

The board of directors’ conference room is lit by art glass windows and skylights and is furnished with Wright-designed table and chairs.162 In several photographs, the row of clerestory windows above (some of which are open to allow for ventilation) are clearly visible at the intersection of the walls and ceiling.

Mounted on upright posts that overlook the tellers’ space are four ornate lighting fixtures. They are identical figurative sculptures of the Spirit of Mercury (“the patron of commerce and finance,” according to Wright) in a form created by Richard Bock, a German-born American artist who was frequently commissioned by architects (including Wright, repeatedly) to create site-specific art.163

There are also decorative references to the abstract terra-cotta designs that are on the exterior second floor, as well as smaller versions of a typically Prairie School concrete urn that occurs in larger versions on the exterior second floor, above the hotel entrance and, on street level, at the door of the transitional waist.164

Unlike the interior of the bank, the alterations to its exterior are reasonably well documented, mostly because of its easy access. There are quite a few news photographs, amateur snapshots and vintage postcards (some colorized) that document the changes (as well as stages of neglect) to the building’s exterior from year to year. To make a long story short, it was ravaged architecturally. The interior was demolished, and the outside all but died as well.165

In fact, the bank as Wright designed it survived for less than twenty years. Beginning about 1920, the community (like those in other farming states) was crippled by various economic crises, largely farm-related. Having declared bankruptcy, the City National Bank was forced to close, along with other Mason City banks (at one time there had been as many as five), with the sole exception of the City National’s longtime competitor, the First National Bank.

During the 1920s, Iowa led the nation in bank failures. To get a clear sense of the crisis, it is helpful to remember (as described by Leland Sage) that in 1920, the number of bank failures “jumped to 167 and in 1921 shot up to 505, then fell back to 366 in 1922. All through the remaining 1920s the number hovered well above the 500 mark each year.”166

TRANSFORMATION AND DECLINE

Soon after, when the foreclosed City National Bank and Park Inn changed ownership in 1926, the new owners (in the hope of financial survival, even revitalization perhaps) decided to convert the bank to walk-in retail stores and office space. In a massive remodeling effort, the bank’s interior was gutted. Its first floor was lowered to grade level, and the once spectacular two-story banking room became two normal floors of standard height. Now, there really were three floors.

On the exterior, the most shocking transformation was the conversion of the bank’s impenetrable walls to glassed-in commercial storefronts. Thankfully, perhaps for expediency, the least exterior damage was done to the upper level, where the topmost original windows were spared, as were the terra-cotta tiles. For many years afterward, those who knew the building’s historical past had only that colorful upper crown to look up at admiringly as they passed the building’s sad remains.167

Under new ownership, the bank and hotel were divided by an interior wall to enable their potential sale as two distinct properties. Thereafter, at least architecturally, it may be accurate to say that the hotel survived better than the bank, although it, too, was modified. At the very least, it remained a hotel (albeit in disrepair and half empty at times) until 1972, when, after repeated foreclosures, it was unsuccessfully changed into an apartment complex.168

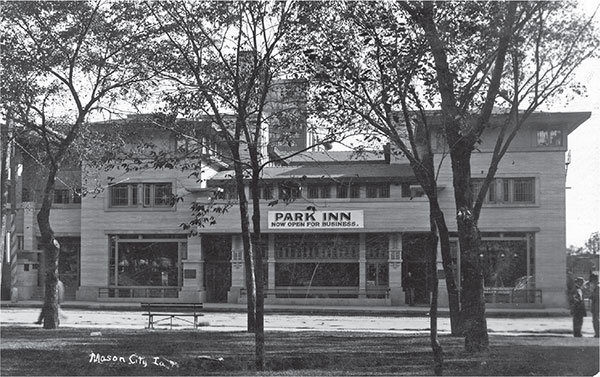

When the Park Inn initially opened in 1910, it had been advertised as “European” because it hoped to emulate the exotic charm and ambiance of overseas bed-and-breakfast hotels. The Park Inn and its rooms were small. There was hot and cold water in every room, but as with most hotels back then (except the most expensive), two adjoining rooms shared a bathroom or there was a bathroom off the hall.

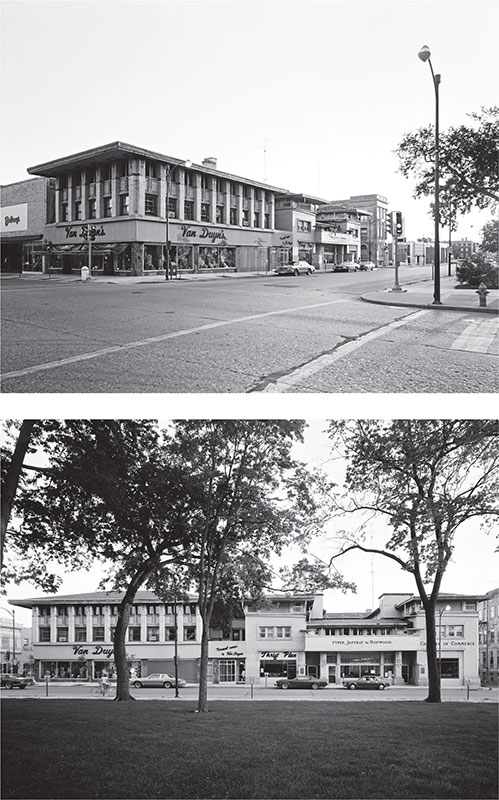

The bank and hotel in 1977, clearly showing the ground floor walls that had become glassed-in storefronts. Historic American Buildings Survey, LOC Prints and Photographs.

Vintage postcard of the Park Inn Hotel entrance, as viewed from the park (date uncertain). Mason City Public Library.

In 1910, the hotel publicity claimed it was a model of “cuisine and comfort.” It was, the ad continued, The dining area, as the Mason City Globe Gazette confirmed, “serves only the ‘finest cuisine with a European flair.’”

a marvelously well planned hostelry, every room of [its] sixty-one rooms but one [in truth, there were only forty guest rooms] being an outside room with art glass French windows, mahogany furniture, Cadillac tables, brass beds with box mattresses, lavatories with hot and cold water, luxurious bath rooms—everything new and sanitary and comfort wooing.169

The Park Inn Hotel was reasonably successful for a dozen years after it opened. Unfortunately, despite the initial send-off and the praise that followed, it had begun to decline irreversibly by 1922.

That year (in the midst of a catastrophic farm crisis) marked the opening of a new downtown hotel, just three blocks from the Park Inn. It was named Hotel Hanford, in honor of the family of the wife of Charles H. MacNider, the Mason City banker whose First National Bank had been the long-term competitor of the City National Bank.170

Vintage postcard of the Park Inn Hotel entrance (circa 1920). Mason City Public Library.

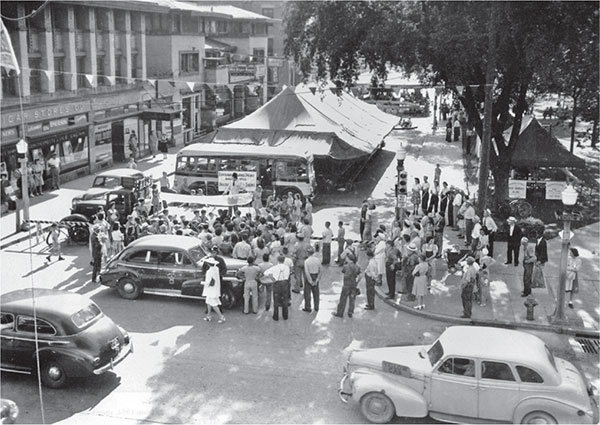

Photograph of a street carnival on State Street in 1943, in front of the City National Bank and Park Inn, which underwent remodeling in 1926. Mason City Public Library.

The new, much larger hotel was undeniably upscale. Its 250 guest rooms were more spacious and luxurious than those of the Park Inn. In addition, the Park Inn rooms were still limited to shared bathrooms, whereas each Hanford room had its own.

For these and other reasons, the Park Inn’s survival was not in the cards. But what looked like an inevitable death would drag on ever so slowly for eight decades or longer.

In 1962, when the film version of Meredith Willson’s The Music Man premiered in Mason City, the Champagne Supper for the extravaganza was held (of course) at the Hanford Hotel. Among the guests that evening were Hollywood celebrities Robert Preston, Shirley Jones, Ronnie Howard, Arthur Godfrey and Hedda Hopper—all of whom stayed at the Hanford Hotel.

In a 1970 article in the Des Moines Register (headlined “Time Cruel to Iowa Hotel by Frank Lloyd Wright”), the Park Inn Hotel’s bar and dance floor were described as “not an inviting place.”171

Pigeons had moved into secluded areas of the building. The roof was leaking, and mold was an ever-present concern. “By 1970,” as described by Katherine Haun, “Mason City residents told visitors: ‘Don’t stay there.’”172

All this was taking place just as there was a growing concern about the nation’s attitude toward the preservation of historic architecture. Four years earlier, the National Register of Historic Places had been created by the federal government so that communities could seek grant support for the faithful restoration of historic buildings of significance.

Among events that signaled hope for the survival of Wright’s bank and hotel were the efforts of a committee of Mason City citizens, who, in 1972, successfully applied to have the bank and hotel listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

WRIGHT’S ACHIEVEMENT

In 1997, architectural historian Robert McCarter described Mason City’s City National Bank and Park Inn as “a masterpiece of integration.”173

It is, he went on to say, “one of Wright’s most interesting designs of the period, though it is rarely studied.” Its integrative richness comes from the back-and-forth dance of connections between the two buildings. Through “complementary massing and fenestration,” McCarter concludes, “Wright brings the disparate functional elements into a highly resolved and beautifully proportioned composition.”174

Current exterior view of the City National Bank, as restored in 2011. In the end, the cost of the project was more than $18 million. Author’s photograph.

Despite Wright’s achievement, it would not be an easy task to preserve the bank and hotel, much less to restore them to the condition that he had initially planned. As Haun documents, an impassioned exchange of opinions ensued. It went on for years (and still goes on to some extent). Genuine restoration of the building(s) would require an enormous commitment of funds. Funding sources are limited, and the collection and distribution of funds necessitates painful decisions about what is of foremost importance in life—in this case, the life of a city.

Besides, what could possibly be achieved? As was asked in 1989 in the Mason City Globe Gazette, in an editorial on the fate of the bank and the hotel, “What function can support that form?” No investors could ever recover their funds. And the city could never afford to restore and then maintain it. Without private funding, the editorial continued, the building(s) will continue to be “a crumbling anachronism at worst; at best a lifeless museum memorializing a man who left his mark on the city 79 years ago.”175

Current interior view of Wright’s City National Bank, which now functions as an events facility. Photograph by Daniel Hartwig (Creative Commons).

That editorial was written twenty-five years ago. Since then, a miracle has evolved. In truth, it was not really a miracle but the consequence of efforts by Mason City citizens (as well as others from outside) that began as early as 2000 and finally reached a crescendo in 2011. Among those citizens were several who were owners (and protectors) of homes of equal significance in the Rock Crest/Rock Glen neighborhood.

The rescue of Wright’s Mason City buildings is a long and meandering story, the details of which have been documented in various publications, available to visitors at the city’s McCoy Architectural Interpretive Center, as well as at the gift shop of the Wright on the Park Headquarters. Suffice it to say that, through phenomenal achievements in historical research, fundraising, cooperation and consent, the buildings that had formerly been the City National Bank and Park Inn were restored and opened once again in 2011 as the Historic Park Inn Hotel.

Detail of a current view of Wright’s Historic Park Inn Hotel. Photograph by Daniel Hartwig (Creative Commons).

How fortunate are we today to be able to witness directly—in a visceral and immediate way—a breathtaking triumph in building design that reaffirms human achievement.

Entrance to the Historic Park Inn Hotel after restoration. Today, it functions prominently as a hotel, restaurant and events facility. Photograph by Daniel Hartwig (Creative Commons).

The Skylight Room in the restored Historic Park Inn Hotel interior. Photograph by Bobak Ha’Eri (Wikimedia Commons).

In its inspiring restored state, the Historic Park Inn Hotel now thrives as a cultural icon that functions year round as a hotel, restaurant and events facility, where guests (some of whom have traveled here from other countries) can once again experience “bed-and-breakfast” in the setting of an architectural masterpiece.176