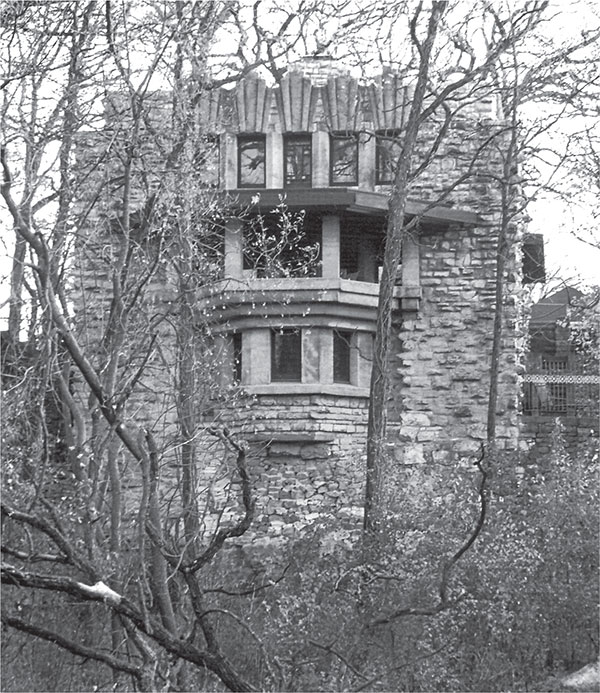

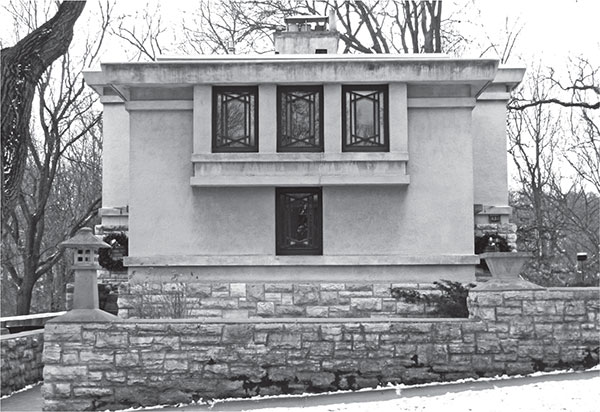

A view of the back of the Melson House in its restored state and the limestone bluff it rests on. Photograph courtesy Peggy L. Bang ©2015.

4

ROCK CREST/ ROCK GLEN NEIGHBORHOOD

In 1903, a Mason City building contractor and real estate developer named Joshua G. Melson purchased twenty-two acres of land on the east edge of the city’s downtown. The site was within five blocks of the busy intersection of Main Street (later Federal Avenue) and State Street, where, seven years later, the new City National Bank and Park Inn would be erected.

Melson’s property was an undeveloped subdivision overlooking Willow Creek, a tributary of Lime Creek, now called the Winnebago River. The terrain on the banks of the river included limestone bluffs on the eastern high ground side, part of which is known today as Rock Crest. On the opposite side of the stream, there was low ground on the western plane, called Rock Glen.177

RIVER HEIGHTS

Melson subdivided his (the higher) portion of the land, naming it River Heights, and prepared to offer lots for sale. The land on the opposite side of the stream would soon be owned by others, among them the bankers and lawyers who would commission Wright’s design of the bank and hotel.

As mentioned earlier, while Wright was working on the City National Bank and Park Inn in 1908, he also designed a Prairie School home for a local doctor and his wife, now known as the Stockman House.

A view of the back of the Melson House in its restored state and the limestone bluff it rests on. Photograph courtesy Peggy L. Bang ©2015.

Joshua Melson was a building contractor who had dabbled in house design. While not trained as an architect, he had an insatiable interest in architecture and had worked as an apprentice to another Mason City contractor and self-taught architect, E.R. Bogardus. He admired Wright’s proposal for the Stockman House.178

From all reports, Melson was unusually open to innovation, architectural and otherwise. He was the owner of one of the first automobiles in Cerro Gordo County (it was the first electric car in the state), and in 1919, he acquired the area’s first passenger airplane, a Canadian wartime Curtiss surplus plane, and he trained as an amateur pilot.179

When Melson saw the Stockman House, it occurred to him to talk to Wright about designing a distinctive home for himself (an unusual showcase dwelling) in the River Heights subdivision, in the hope of encouraging others to build. Melson and Wright arrived at a general agreement, and in time, Wright came up with a tentative plan, a drawing of which was published in 1911 in the Wasmuth Portfolio (albeit mistakenly labeled).

As it turned out, the timing was unfortunate, to say the least. Before any of this could become a reality, Wright was not only out of the picture in relation to Mason City, but he was literally out of the country as well. The Stockman House had been completed in 1908, and construction of the City National Bank and Park Inn began in April of the following year.

However, as noted earlier, 1909 was the year that Wright’s outrageous marital scandal broke, and in late September, he and Mamah Borthwick Cheney left for Europe. Their adultery became publicly known when the story came out (with the headline “Leave Families: Elope to Europe”) in the Chicago Tribune on November 7, 1909.180

Most likely, as Paul Kruty notes, “Melson’s—as well as Markley’s and Blythe’s—rejection of Wright began on that day.”181 Or, as Robert McCoy has said, from that day on, among Mason City residents, Wright was persona non grata.182

Wright had also become an outcast in his hometown, as architect Richard Neutra found when he arrived in Chicago from Europe:

People were flabbergasted that I should have picked up the ideals of a great Chicagoan in a European library, and looked at each other in amazement. …Wright was not a famous man. He was a terrible man. Had not the Chicago papers brought out lurid stories about him? He had to leave town—and here I was coming from Vienna to look for a person like this and his work!183

UNDER CONSTRUCTION

Fortunately, even though Wright could no longer oversee the actual construction of the City National Bank and Park Inn, it was reluctantly taken on by his recent associate, Chicago architect William E. Drummond.

Drummond had studied briefly at the University of Illinois School of Architecture. For a short time, he worked for Louis H. Sullivan, then moved on to be the draftsman for some of Wright’s most celebrated early projects, including the Cheney residence in Oak Park; the Susan Lawrence Dana House in Springfield, Illinois; and the Larkin Building in Buffalo.

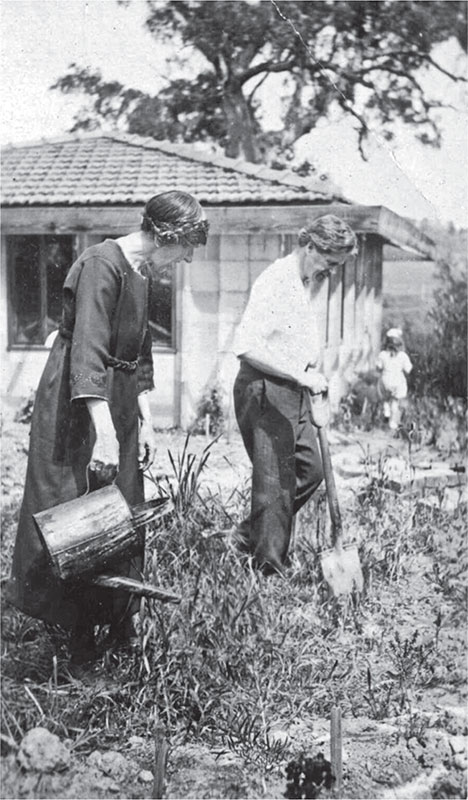

While managing construction of the City National Bank and Park Inn, Drummond took on a sideline assignment (the client was Joshua Melson) to design a speculative residence in the River Heights subdivision, which Melson then sold to Curtis Yelland (a local postal employee and Melson’s friend), a structure since referred to as the Yelland House.184

Having worked for years with Wright and other Chicago architects, as well as independently, Drummond was undoubtedly well qualified. The posture of the Yelland House is conspicuously horizontal, an effect that is visually reinforced by its pronounced overhanging eaves, lateral wood banding and board and batten siding (a typically vertical feature, as in Grant Wood’s American Gothic, in this case horizontal).

Almost a century later, the house was all but completely destroyed by a fire in the winter of 2008. Slated for demolition, it was purchased and restored, including the detailed replacement of its built-in interior details.

Wright returned from Europe in October 1910. Less than a month later, on November 5, there was a formal opening of the City National Bank and Park Inn Hotel in Mason City, an event that Wright did not attend.

An article that appeared that day in the Mason City Times praised the tandem structure as a “magnificent new building,” while it also cautioned that some of the project’s components remained unresolved.185

Despite his absence from the gala, it was in that same issue of the newspaper that Wright’s own account of the building was published (with clear credit to his authorship). As mentioned earlier, this same text was reprinted later in the December 1911 issue of the Western Architect.

Regardless of venomous rumors about the sinfulness of the architect, when their bank and hotel were featured with such prominence in a national magazine, “the whole town,” Paul Kruty surmises, “must have felt a sense of pride. Modern architecture had taken hold in Mason City.”186

Meanwhile, Wright’s erstwhile building commitment—that of designing a showcase home for Joshua Melson—remained completely in limbo. For whatever reasons, Melson had grown dissatisfied with Wright’s proposal (no doubt, he was also disgruntled with Wright), which was a half-hearted adaption of a floor plan that Wright had used previously and that he and others would use as a point of departure again.

Before leaving for Europe, at the last minute, Wright had reached an agreement with another Chicago architect, Herman Von Holst, to temporarily manage his architectural accounts, which included about twenty pending commissions (some of which even lacked drawings).187

MAHONY’S CONTRIBUTION

In his absence, the bulk of Wright’s unfinished work was done by Marion Mahony, who was, as mentioned earlier, one of the first female architects in the country. She was unequaled as a draftsman and had closely worked with Wright for fifteen years. In fact, a substantial number of the drawings in the Wasmuth Portfolio are thought to have been made by her (some of which she signed, some not).188

To this day, despite her achievements, Marion Mahony Griffin remains largely unheard of, in part because, as the saying goes, her light is usually hidden beneath a bushel basket.189

In her case, the basket is twofold: On the one hand, she is outshone by the brightly blinding legend of Frank Lloyd Wright, whose fame she partly enabled. At the same time, her achievements also pale beside the better-known work of her soon-to-be husband, architect Walter Burley Griffin, whose projects she also contributed to, with and without credit.

As often happens in collaborations, especially those of husband and wife (recall, for example, the cooperative works of Gustav Klimt and Emilie Flöge, Charles Rennie Mackintosh and Margaret MacDonald Mackintosh and Charles and Ray Eames), it is frequently unclear which aspects each was responsible for.

Alasdair McGregor views it in this way:

Where Walter’s pencil stopped and Marion’s took over is impossible to say. Architectural creativity, from conceptual sketches through to working drawings and construction detail, should, at its ideal best, be a seamless process, with the finished building the collective and cumulative invention of any number of minds.190

Disadvantaged from the start simply by being a woman (at a time when women’s suffrage was a volatile issue), Marion Mahony Griffin was probably also discredited for too freely voicing opinions that were laced with “mordant humor”—a humor that was possibly even more mordant than Wright’s.191

Lastly, in terms of her being neglected, it probably has not helped that her family name (Mahony not Mahoney) is nearly always misspelled in research articles and books and just as frequently mispronounced (MAhon-ee, not Ma-HO-NEE), although the Australians, she noted, almost always got it right.192

In 1894, the then unmarried Mahony had graduated from the MIT School of Architecture. Soon after, she was hired by her architect cousin, Dwight H. Perkins, to work as an apprentice in Chicago.

Other architects were headquartered in the same building, Frank Lloyd Wright among them, and in 1895, she became Wright’s chief (and only) delineator, as well as his first employee.

In that capacity, while working primarily as a draftsman, she also, on occasion, designed furniture, art glass windows (she designed the windows for the Robie House), decorative panels and (while Wright was in Europe) some of the actual buildings themselves. In the year that Wright was absent and too distracted to reply to inquiries, Mahony recalled, “I had great fun designing.”193

Mahony had been working for Wright for about six years when, in 1901, Wright hired another young Chicago architect named Walter Burley Griffin, who stood out from his colleagues because he was as much devoted to landscape and garden design as to residential architecture. Griffin soon played a prominent part in Wright’s studio in Oak Park. His role was especially critical when a project included a garden design, as in the well-known houses for Ward Willets and Darwin Martin.

It appears that working relations between Wright and Walter Burley Griffin were more or less uneventful until 1905, when Wright and his wife, Catherine Tobin Wright (the spouse and mother of his children, whom he would soon abandon), went to Japan for several months, during which Griffin was put in charge of the Oak Park firm.

When Wright returned from Japan in May, he was less than happy with the handling of various matters in his absence. In addition, as was frequently the case, he had run out of money.

Lacking the funds to pay Griffin what he owed him, he instead offered to give Griffin a selection of the Ukiyo-e prints he had purchased on the trip. Griffin protested, but Wright stood by his offer and declared that Griffin’s debt had been settled.194

Not surprisingly, this did not sit well with Griffin, and by the following spring, he had resigned to start his own architectural firm. Bad blood ensued for many years and eventually led to such bitterness that the two no longer spoke.

At around the same time, a handful of others were working for Wright, among them William Drummond (who would also resign for nonpayment) and Barry Byrne, both of whom, as noted earlier, would soon become key players in the architecture of Mason City.

In addition, Marion Mahony was increasingly indispensable as Wright’s chief draftsman, in the course of which she made the drawings for his Mason City projects, including those soon to appear in the Wasmuth Portfolio.

In September 1909, just two days after Wright’s departure for Europe, she was completing the drawings for the proposed (but later rejected) home that Wright had designed for Joshua Melson on Riverview Heights.

GRIFF IN AND MASON CITY

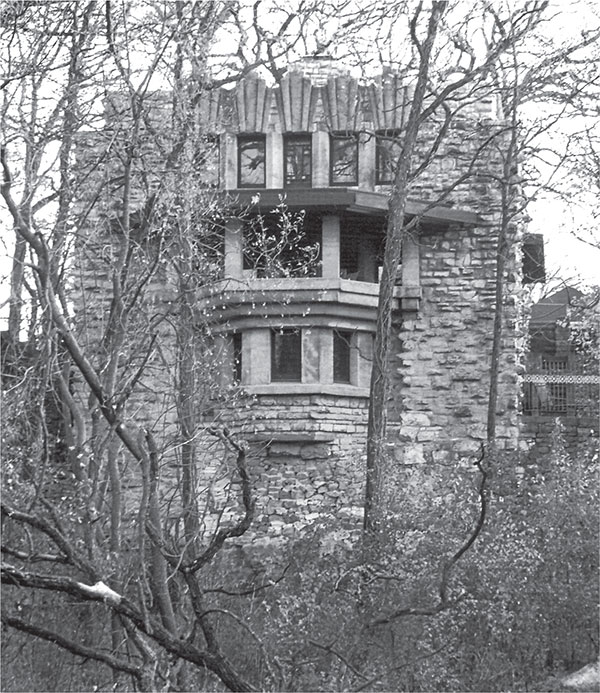

In the meantime, although Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony were no longer working together in Wright’s studio, the two had become a couple. In June 1911, they eloped and married hurriedly, even though Griffin was so beset by deadlines that there was no possibility of a honeymoon.195

One cause for his being so busy was that he (with Marion working beside him) was preparing an entry for an international competition for the design of the new federal capital city of Australia, named Canberra.

Given his background in landscape design, Griffin was especially well suited, since the project required not only the design of buildings but also the overall plan of the city itself.

Quite a lot is known about this phase of the Griffins’ life because Marion later wrote an autobiography titled “The Magic of America.” Never officially published, it has survived as a 1,400-page typescript, supplemented by 650 illustrations.196

Throughout that manuscript, she is forthright in her memories of architects and others—and especially of Frank Lloyd Wright, whom she described as an “incubus” whose “malicious vanity” had functioned like a “cancer sore” on Chicago architecture.

In contrast, she had far nicer things to say about Wright’s long-suffering client from Mason City, Joshua Melson. He was easily dismayed, so much so that Marion’s nickname for him was “Don Melancholio.”

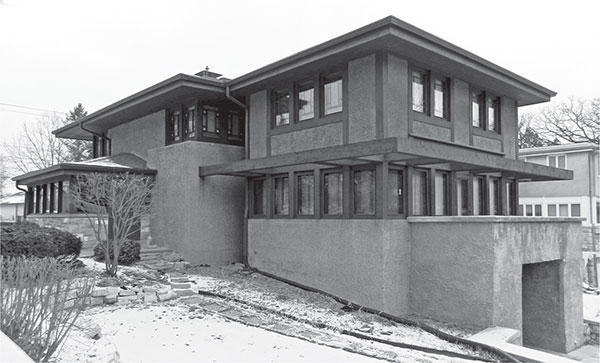

One day in 1911, while visiting Chicago, Melson appeared at Marion’s place of work, shared his disappointment with Wright’s design for Melson’s house and talked with her about the possibility that she might prepare a rendering of the entire riverside neighborhood, which he, Blythe and others were starting to plan.

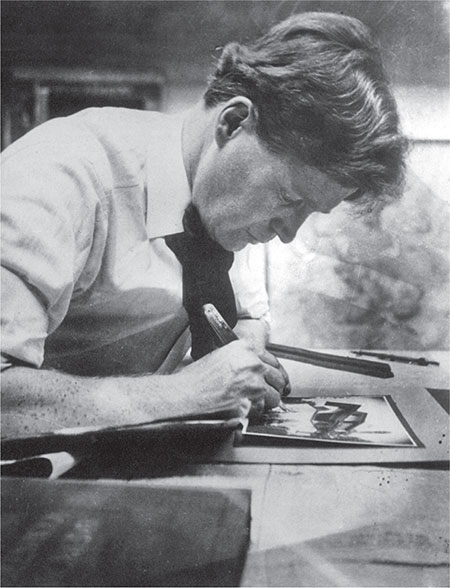

Walter and Marion Griffin gardening in Australia (1914). National Library of Australia (Wikimedia Commons).

She responded with moderate interest but then declined the offer. If anything, if they needed a plan for a landscape, she told Melson, they should commission her husband, although he was impossibly busy.197

Nevertheless, it all worked out. At some point early in 1912, Walter Burley Griffin traveled to Mason City for the first time to inspect the entire Rock Crest/Rock Glen setting. He talked at length with Melson, Blythe, Markley and other associates about his ideas for the subdivision.

In addition, Griffin and Melson spoke about a new design for Melson’s house. It was a breakthrough discussion. Griffin proposed a truly remarkable plan in which (unlike in Wright’s proposal), the Melson House would not step back timidly from the edge of the limestone bluff. Rather, it would dramatically and precariously perch on the very edge of the precipice, overlooking the river (and Rock Glen) in the back, while easing in to level land in the front.198

Among the most vivid accounts of Griffin’s design for the Melson House is that by Alasdair McGregor, in which he describes it as follows:

Rather than approaching the cliff on Melson’s site as something to be feared and avoided—as if seized by an attack of architectural vertigo—Griffin designed his building to erupt in a burst of vertical rock, all the way from its Silurian foundations. This was no Prairie School expression of ground-hugging horizontality topped with wide eaves and a prominent pitched roof. Instead, in its profound respect for both the terrain and materials garnered from the site, it was a masterly essay in organic design.199

Following Griffin’s visit, Melson was all but ecstatic. When her husband returned to Chicago, Marion remembered, he had Don Melancholio Melson “in his pocket.” Henceforth, “melancholy flew out and an enduring enthusiasm filled…our Don.”200 What a fortuitous opportunity for both parties. What could possibly go wrong?

ROCK CREST/ROCK GLEN

In the end, what went wrong was what went right. Walter Burley Griffin’s design for the Australian federal capital, Canberra, had been one of 137 entries from architects throughout the world. He had prepared it in collaboration with his wife, who made astonishing drawings on linen.

In late May 1912, their submission was awarded the top prize in the Australian competition (among prestigious runners-up was Finnish architect Eliel Saarinen), and suddenly they were locked in to an all-consuming challenge on the other side of the world—one from which Griffin would never return.

When the American architectural community learned that Walter Burley Griffin had won an international competition, his speaking invitations increased. While traveling to those, he continued working on multiple building projects, notably the Stinson Memorial Library in Anna, Illinois, and an ambitious, if sadly ill-fated, community plan for the Trier Center Neighborhood in Winnetka (funded with the prize he won from the Australian competition). Yet somehow Griffin found the time to continue to develop the Mason City project.

In July 1912, he returned to Mason City to confer for several days with Melson and the others. On that trip, he brought with him preliminary drawings for the Melson House, as well as that of Harry D. Page, who had since become part of the project. He also shared with everyone his overall plan for the landscape, the subdivision plots and the locations of all the houses.

Despite the challenge of reaching a group consensus, Griffin and his Mason City clients succeeded in doing just that. They even agreed on the neighborhood’s name (most likely Griffin’s proposal): it would be officially known as Rock Crest/Rock Glen. Soon after Griffin’s departure, the work on the landscape was started, bids were sent out and the actual housing construction began.201

The first to be completed was the Page House.202 It was built in 1912 for a local lumber merchant who had abandoned an earlier house design (proposed by the well-known firm of Purcell and Elmslie in Minneapolis) in compliance with Griffin’s request that he alone should have free rein in designing all the houses at the Rock Crest/Rock Glen site.

The second was the structure known as the Arthur Rule House, also completed in 1912.203 In fact, it was commissioned by law firm partner James E. Blythe, but he lived in it only briefly while awaiting the construction of another more complex residence (also designed by Griffin) in the same neighborhood. When his new home was completed, Blythe sold the earlier one to Rule, who was a partner in the firm.

The third to be completed was a Griffin tour de force. Designed for James E. Blythe himself, it was the largest of the houses and one of the last in which the construction was managed by Griffin. It made early innovative use of reinforced concrete, but it also stands apart in terms of architectural style. While well within the look and feel of Prairie School tradition, it has a nuanced resemblance to Meso-American or Mayan architecture. It was the neighborhood’s first split-level home. It “stands today,” historian H. Allen Brooks has said, “as a significant monument in the annals of American architecture.”204

Photograph of the Harry D. Page House in Mason City, in the Rock Crest/Rock Glen neighborhood. Photograph by Daniel Hartwig (Creative Commons).

Photograph of the Arthur L. Rule House. Photograph by Daniel Hartwig (Creative Commons).

Photograph of the James E. Blythe House in Mason City. Photograph by Daniel Hartwig (Creative Commons).

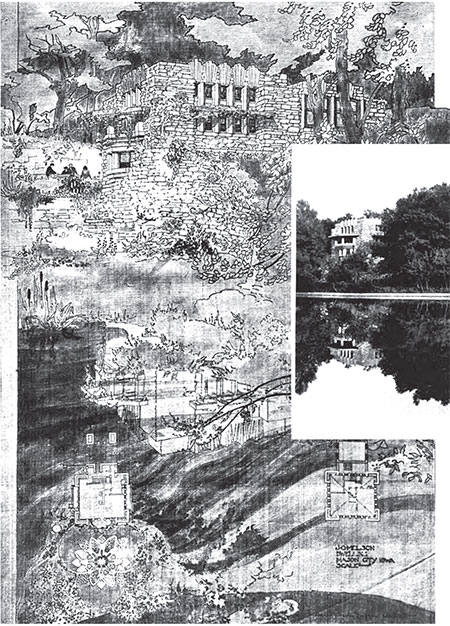

Meanwhile, 1913 was a whirlwind year for Walter and Marion Griffin. In the August issue of the Western Architect was a thirty-page sequence of drawings, photographs and text on Griffin’s recent and in-process projects. It included detailed overviews of his plans for the Trier Center Neighborhood, the architect’s own home, the Ricker House (in Grinnell, Iowa), Rock Crest/Rock Glen (in Mason City, including details of the Rule House), Marion Griffin’s rendering of the Melson House, a teasing peek at early plans for Canberra and much more.205 Soon after, his work was featured in the Architectural Review.

AUSTRALIAN OBLIGATIONS

Somewhat earlier, it had also become evident that opposition was growing among conservative Australian officials about Griffin’s plan for Canberra. He agreed to travel to Sydney for a few weeks to look more closely at the site. He arrived there in August 1913 and, in the end, extended his stay for several months.

By the time Griffin left Australia in November, those who opposed his plan had been (ineffectively) silenced, and in an awkward power struggle, he had been appointed the federal capital director of design and construction. Under contract, he agreed to return to Australia in a few months to resume his supervisory work and to remain there for about three years.

Marion Mahony Griffin’s rendering of her husband’s design for the Joshua G. Melson House, as published in the Western Architect (August 1913).

Arriving back in Chicago by mid-December, Griffin had only two weeks before he was due in Mason City for a meeting with his Rock Crest/Rock Glen clients. Although he didn’t know it, it would be his final meeting with them.206

He had been all but unknown on the two occasions when he had visited Mason City before. Now, as the recipient of an international award, he was a celebrity. He was given top-rank coverage in local news reports. He even got undeserved credit when the newspaper mistakenly mentioned that he (not Frank Lloyd Wright) had designed the City National Bank and Park Inn.

At the time of that visit, the Melson House was nearly completed, and the Blythe House was under construction. The visit was largely a formality and included the presentation of gifts from the architect to his clients. It is interesting to learn (recalling Wright’s bungled relations with Griffin) that Griffin’s gift to the Blythes was a selection of Japanese Ukiyo-e prints.207

As for Melson, he could not have been happier. His house was attracting attention, just as he had always hoped. Townspeople had begun calling it “The Castle” (some Mason City residents still refer to it as that).

Later, Marion Mahony Griffin recalled the day when Melson (“the old ‘sad face’”) showed up again at the Chicago office “saying that he was going to have to charge up his electric bills to Mr. Griffin”—and then he laughed—because “everyone, and that was the whole town [of Mason City], who crossed the bridge…whether pedestrian or motorist, stopped to look up the river at the fascinating sight of Rock Crest’s initial building.” As a result, she continued, Melson “couldn’t resist the temptation of keeping his whole house lighted up to make the most of a spectacle of it.”208

During this final visit to Mason City (in late December 1913), Griffin explained to Melson that he and Marion were leaving soon for Europe—specifically, Vienna—to meet the famous secessionist architect Otto Wagner.209

Would Melson like to come along?

Melson agreed, and from all reports, it was a pleasurable escapade. (It’s not clear if they were accompanied by Millie Melson, Melson’s wife, who was suffering from heart trouble and would die of a stroke in 1915.)

At the conclusion of that venture, the Griffins returned to Chicago, then departed for Australia in mid-April, arriving there in early May.

However, before he could leave for Australia, Griffin was faced with the problem of finding someone who would be willing—and able—to manage his Chicago architectural firm during his anticipated three-year absence. After considering various options, he made an offer to Chicago architect Barry Byrne, a former Griffin co-worker who had also been a draftsman for Frank Lloyd Wright.

Byrne had relocated to Los Angeles, where he was less than happy. He accepted Griffin’s offer, and the name of the patchwork firm became Griffin and Byrne. Byrne then moved back to Chicago, where the mutual expectation was that, in Griffin’s absence, he would carry out Griffin’s intentions for his ongoing projects. If any significant problems arose, Griffin would be consulted.

AGREEMENT DETERIORATES

The Griffins soon left for Australia, and for a short time, things were uneventful at the Chicago office. Unfortunately, Griffin had not realized the extent of Byrne’s continued loyalty to Wright.

When Wright expressed annoyance to Byrne about his new partnership with Griffin (to whom Wright was no longer speaking), Byrne answered that his greatest dread was that he, too, would end up on Wright’s list of enemies. His commitments to Griffin, he reassured Wright, were secondary and merely a “business” arrangement.210

Only months after the Griffins’ departure for Australia, apparent lapses began to occur in the implementation of Griffin and Byrne’s agreement. As time passed, Byrne’s updates all but ceased, and in some cases, substantial changes in buildings were made without Griffin’s knowledge.

To be sure, Griffin’s workload in Australia was such (he had faced bitter opposition to his ambitious city plan) that he could not possibly micromanage the Chicago office—after all, that’s what Byrne was hired to do.

Back in Mason City, a familiar figure returned to the stage. It was Charles H. MacNider, the prominent businessman, banker and longtime competitor of Markley and Blythe. A few years earlier, he had built the new eight-story First National Bank, perhaps in part as a challenge to Wright’s City National Bank and Park Inn. In a few years hence, he would also build the Hanford Hotel, which all but ensured the certain decline of the Park Inn.211

Soon after Griffin’s departure for Australia, MacNider approached Byrne about remodeling his own mansion, a house in the Greek Revival style.212 Byrne agreed to do so, although in style and philosophy the structure was the inverse of Prairie School architecture.213 While it was Byrne’s decision to take this project on, the remodeled house was credited to the firm of Griffin and Byrne. Yet he never mentioned it to Griffin.

A further complication was that Byrne began to have personal differences with a client who had reached an earlier agreement with Griffin.

That client, Samuel Davis Drake, wanted a Prairie School home in the Rock Crest/Rock Glen neighborhood.214 He had purchased land on Rock Crest from Melson, and Griffin had supplied the plans.

However, with Griffin in Australia, Byrne soon concluded that Drake was impossible to work with, and he chose to cancel the project. There may have been good reason for this—but apparently, once again, he failed to let his partner know.

In search of a new architect, Drake approached a Mason City firm called J.H. Jeffers and Company. The person on the company’s staff in charge of Drake’s house project was a Scandinavian immigrant, a somewhat furtive architect named Einar Broaten. Broaten’s firm, as well as his client, was greatly pleased with the Prairie School result of the Drake House. Broaten became a partner, and the firm was soon renamed Jeffers and Broaten.215

Broaten was born in Norway in 1884 and appears to have come to the United States prior to 1912. He was active as an architect in Mason City and nearby Iowa communities for at least a dozen years, until 1924. It is believed that he designed about thirteen buildings in Mason City, Clear Lake, Hanlontown, Garner, Hampton, Sheffield and West Bend, many of which are exemplary of Prairie School architecture.

In Buildings of Iowa, David Gebhard and Gerald Mansheim conclude of Broaten that, if in fact he did design the houses attributed to him, he “should be placed within the front ranks of the Prairie movement.”216

Regarding Broaten, it is an awkward coincidence (as noted by Kruty) that the offices of the Jeffers firm were located in none other than Charles H. MacNider’s First National Bank building. The same source also mentions that, at some point, when Broaten’s Drake House was featured in a magazine, it was mistakenly credited to Frank Lloyd Wright.217

It is sometimes rumored that Einar Broaten’s potential as an architect was eventually undermined by a recurrent health issue. For whatever reason, Broaten left Mason City in 1927 and moved to Fergus Falls, Minnesota. There he formed an architectural firm called Broaten and Foss with Magnus O. Foss (whose architect father had also immigrated from Norway). In February 1948, at age sixty-three, Broaten was reported missing. Nine weeks later, his body was found beneath a bridge in the river in Fergus Falls.218

LIMITS OF MODERNISM

If the halcyon days of modern-era buildings in Mason City can be said to have begun in 1908 with the arrival of Frank Lloyd Wright, it might also be said that they started to fade as early as 1917, in the year America entered World War I.

Recalling what happened in subsequent years, it’s clear that Wright’s three buildings (the Stockman House, City National Bank and Park Inn) were at times in danger of being destroyed or ruined through remodeling. As for the Rock Crest/Rock Glen houses, while not threatened by demolition, they, too, were sometimes compromised by remodeling. Meanwhile, the Rock Crest/Rock Glen development always fell short of Griffin’s original plans.219

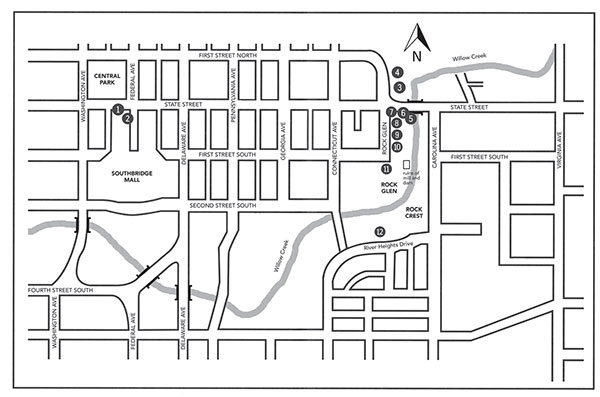

This street map of downtown Mason City, Iowa, shows the locations of its major historic Prairie School buildings. At the top left is Central Park. At the turn of the nineteenth century, Federal Avenue was known as Main Street, and the city’s busiest intersection was at State Street and Main. The three buildings designed by Frank Lloyd Wright are the Park Inn Hotel (1), the City National Bank (2) and the Stockman House (3), shown in its current location (having been carefully moved and restored).

Adjacent to the Stockman House Museum is the Robert E. McCoy Architectural Interpretive Center (4). By walking south across State Street, one enters the two-pronged neighborhood that was planned by Walter Burley Griffin, with its two sides bordering Willow Creek.

The lower side is called Rock Glen, while the side overlooking the bluffs is called Rock Crest. The houses on State Street in Rock Glen include the Sam Schneider House (5), the Hugh Gilmore House (6) and the E.V. Francke House (7). Walking south on Rock Glen Lane, one finds the Arthur Rule House (8), the Tom MacNider House (9) and the Harry Page House (10). Continuing to the corner of Rock Glen Lane and First Street Southeast, there is the James Blythe House (11), from which one can see across Willow Creek to the limestone bluffs of Rock Crest, on top of which is Griffin’s conspicuous masterpiece, the Joshua G. Melson House (12). Other significant dwellings are found throughout the city, some of which were designed by other Prairie School architects, among them William Drummond and Einar Broaten. Author’s diagram.

Initially, Griffin had anticipated the inclusion of nineteen houses.220 In the end, only seven of those were built, all single-family dwellings. Five had been designed by Griffin (the Page, Rule, Melson, Blythe and Schneider Houses). Two others (Gilmore and Francke), while part of the project, were largely designed by Barry Byrne, with allegedly less than full regard for the initial ideas of Griffin, who was in Australia by then.

There are other houses that might also be included. Among these are the Drake House (designed by Broaten) on Rock Crest and, in Rock Glen, the Tom MacNider House.221 The latter, designed some forty years later (in 1959) by Wright associate Curtis Besinger, is not strictly a Prairie School house but closer to what Wright would eventually call Usonian. And there is, of course, the Yelland House, designed by William Drummond.

In the long view of Griffin’s achievements, it should come as no surprise to learn that the house in Mason City that stands above the others (not only literally) is the Melson House. As H. Allen Brooks has said, it is “a master stroke” in which Griffin “turned the cliff to his advantage,” with the result that the building is “partly hewn, [and] partly growing from the striated cliff.”222 Amazingly, as Hurley notes, “although the almost fortress-like structure appears to be part of the cliff face, the interior is open and spacious, human in its scale, proportions, and liveability.”223

The Melson House in its current restored state (2016). Note the interplay of shadows. Author’s photograph.

The drive-through garage for the Melson House, on the front side of the house, has two pairs of doors, eliminating the need to back up. Author’s photograph.

In addition, the Melson House comes with exuberant tales, some of them even more colorful than Don Melancholio’s mood swings. For example, it is said that Griffin, when the building’s outside walls were done, celebrated by climbing (rock by rock) to the roof of the building from the banks of the river below it.224

In another anecdote, there are photographs that confirm that a one-time owner of the Melson House decided in the 1950s that it would look more attractive if pink paint were applied to the outside wooden trim and the concrete mullions.225

When the lurid result was photographed and published, it somehow reached Australia. Some years later, when an American photographer traveled to Australia to document Griffin’s stone-walled houses there, he found that some of the owners had added the same pink to their own Griffin homes, thinking that Griffin had planned it that way.226

Fortunately, this astonishing structure was purchased in 1994 by new owners (Roger and Peggy Bang) and painstakingly restored.

DESIGNING FOR NATURE

In 1914, the very same year the Griffins arrived, Australia entered World War I. While opposition to Griffin’s plan for Canberra was fueled by ferocious political strife, there were also reassessments of the government’s priorities and resulting funding cuts. There were even wartime suspicions expressed about Griffin’s non-Australian status, as well as his past admiration for the work of German architects.

Prior to settling there, the Griffins had nothing but admiration for Australia and its people. But having lived there for a year, their views were radically reversed. As James Weirick has described it:

Caught in a complex web of jealousy, intrigue, indifference and misunderstanding, played out against the social hysteria of Australia during the First World War, their [the Griffins’] faith in Australia as a rational, modern society was deeply shaken.227

By 1918, Griffin was at wit’s end. He was distressed by the endless delays and fierce opposition to most of his plans. It was even suspected that bureaucrats had purposely supplied him with incorrect data as a way to undermine his work.228

He resigned soon after and (along with other projects) turned instead to a new, long-term proposal that resembled his previous (and largely unsuccessful) attempts to build planned communities—the Trier Center Neighborhood in Winnetka and the Rock Crest/Rock Glen neighborhood in Mason City.

In 1920, the Griffins formed a company called the Greater Sydney Development Association (GSDA), with which they were able to purchase 650 acres of undeveloped land in Sydney Harbor, four miles of which bordered the water. From the outset, their plan was to gradually build up an unprecedented community in which the Australian bush and innovative house designs would coexist harmoniously, where buildings and the landscape merge.

There would be “no boundaries, [and] no fences,” and roads and footpaths would comply with the byways already implied by the contours of the land. A master at choosing evocative names, Griffin christened it Castlecrag.229

Not surprisingly, given the emboldened blending between the house and limestone bluff in Mason City’s Melson House, Griffin’s Castlecrag designs have much in common with that earlier project. Of the forty-five houses that Griffin designed for Castlecrag (fifteen of which were actually built), one that is frequently cited as among the most successful is the Fishwick House.

Built in 1929, the Fishwick House was made of the stone from its surroundings. Its appearance, at times, is that of a cave rather than a dominant, conspicuous home, albeit inside it is lavish and large. Like the Melson House, the impression is that it grew out of the land, that the two are inseparable (or at least wholly compatible), in stark contrast to the prevalent goal of agrarian conquest.

Walter Burley Griffin’s design for the Fishwick House in Castlecrag, near Sydney, Australia. Photograph courtesy Ian Tocher ©2012. Used with permission.

Both the Melson House and Fishwick House are exemplars of the practice of Griffin’s belief in “designing for nature,” whereby a building ought to be (in his words) “the logical outgrowth of the environment in which [it is] located.”230

As Frank Lloyd Wright would later say, “No house should ever be on a hill. It should be of the hill. Belonging to it.”231 As do other Griffin designs, the Melson and Fishwick Houses anticipate Wright’s evocation of a later parallel approach, when he designed Fallingwater (the Kaufmann House) in 1936.

DEATH IN INDIA

In the same year, on the other side of the world, the Griffins left Australia for India, where Walter had been asked to design a major university library. He soon had a flood of commissions, and he grew increasingly interested in the possibilities of contributing to the modern architecture of that exotic country.

Tragically, while in India, Walter Burley Griffin grew terribly ill. It was soon determined that his gall bladder had ruptured, and he was taken in for surgery. Five days later, he died in the hospital of peritonitis. Marion was at his bedside at the end.

As she later recalled in a letter to her sister:

As his breath began to fail, I talked to him, told him what a wonderful life I had had with him, how he was beloved by everybody and suddenly he turned and fastened his eyes wide open and round on mine, startled and intense as if it had never occurred to him that he could die and they never left mine till he ceased breathing and I closed them.232

American architect Walter Burley Griffin, as photographed in 1912. State Library of New South Wales, Australia.

Following the death of her husband, Marion Mahony Griffin declined the opportunity to continue his work in India. She moved back to Chicago instead, reestablished family ties and tried to continue to practice as an architect. She described her husband’s and her life at considerable length in “The Magic of America.” She died in 1961.

The ill-fated agreement between Griffin and Barry Byrne was dissolved in 1917. Unable to return to the United States, it had taken Griffin years to learn the truth about activities at the Chicago office.

Years later, when Byrne was interviewed by Studs Terkel in Division Street, he appeared on the brink of confessing to some measure of malevolence. “I’ve always been guilty of a certain artistic snobbism,” he said, “like pushing out of sight all the members of the Prairie School when I got to know Wright. Because they didn’t fly as high as he. Only these last years, remembering my boyhood, I can see how unjust I was to all these people.”233 Byrne died the year Terkel’s book came out, when he was struck by an automobile.

WRIGHT LIVES ON

As for Frank Lloyd Wright’s career, it continued for years, unabated. In 1937, the year that Walter Burley Griffin died (at age sixty), Wright was close to seventy. Wright would not only live for two more decades, but he would also go on to produce important buildings. For example, if he had died at Griffin’s age, he would not have designed the Guggenheim Museum, the Price Tower, Wingspread, the V.C. Morris Gift Shop, the Monona Terrace Center and the majority of his Usonian homes.

Looking back on Wright’s brief connection with Mason City (in total, he was probably present in the town for only a few days), a pesky, unresolved puzzle remains. As mentioned earlier, Wright was able to oversee the construction of the Stockman House in 1908. He also finished the blueprints for the City National Bank and Park Inn, which then opened formally on November 5, 1910.

However, because of the outrageous scandal about his elopement to Europe with Mamah Borthwick Cheney in October 1909, he was unable to manage the construction of those buildings, nor did he attend the opening of the bank and hotel (although he was back from Europe by then).

In the absence of proof to the contrary, it is usually assumed that Wright never returned to Mason City after 1909, so that, although he had access to photographs of the finished buildings, he never saw the structures themselves.

And if by chance he did return to Mason City after 1926, how would he have reacted to the momentous alterations done to the City National Bank or the deterioration of the Park Inn Hotel?

Related to this, posted on the Internet in recent years (as part of a Bonham’s online auction) was a postcard, of which only the message side was shown, handwritten and signed by Frank Lloyd Wright.234

It is dated February 15, 1941, and is clearly addressed to Mason City lawyer James E.E. Markley (Wright’s former client), who was one of those who hired him to design the bank and hotel.

The message on the postcard reads: “On March 13th I will be in Mason City. Please be my guest on February 14th [sic] for dinner at the Hotel. I will look forward to seeing you.”

There are several peculiarities in this message. One is a presumed error on the date of the dinner (he apparently meant to say “March 14th” instead of “February 14th”).

Another question has to do with the dinner’s location. When Wright says “hotel,” is he talking about the Park Inn (one would think so, given Markley’s and his historic involvement with that), or does he mean the Hanford Hotel (regarded then as the city’s upscale place to stay)?

The third problem with the postcard is that Wright is obviously unaware that Markley is no longer living. He had died two years earlier, on October 19, 1939, at age eighty-two.

Why was Wright planning to be in Mason City? Was he merely driving through? Was he meeting with a client in Mason City? Was he wanting—if only out of curiosity—to return to see the physical state of the tandem building(s) that he had designed some thirty years earlier?

In the end, we are left to wonder if, at some moment, Wright actually stood in the presence of the bank and hotel that he had conceived of and produced in 1908.

For this and other reasons, the enigma of Frank Lloyd Wright endures. As do—thanks to the efforts of Mason City citizens—the magnificent, now-restored structures themselves.