CHAPTER 9

Risk Premiums in US Middle Market Lending

Risk premium is an often‐used term in finance to identify factors common to a group of securities where, because that group possesses unique risk‐generative characteristics that cannot be diversified away, there exists an expected or ex ante return attributable to that common factor. Oddly, while called a risk premium, it is a return premium for taking risk.

It is also worth emphasizing that risk premiums accrue to common factors that are nondiversifiable or can't otherwise be eliminated through diversification. Consequently, risk premiums are considered beta and not alpha. When risk premiums are found in less traditional asset classes or investment strategies they are sometimes referred to as alternative beta.

Most familiar to investors, and perhaps the largest risk premium, is the equity risk premium. Stock risk can't be diversified away in portfolio construction so investors, being risk averse, demand a premium return for holding stocks in a portfolio. A wealth of historical data has verified the existence of a stock risk premium, measuring somewhere between 4% and 6% over long periods. Another familiar example is the term structure premium, reflecting the common factor among long‐dated bonds that the risks relating to lending at fixed rates for long periods of time can't be diversified away and deserves a premium return relative to short‐term lending. Again, historical studies have attributed 1–2% in premium return to investing in long dated bonds, unrelated to credit risk.

Modern finance is perhaps currently suffering from risk premium inflation, where investment analysts are mining for and discovering risk premiums in every data set. These efforts have produced, probably prematurely, investment products that harvest alternative risk premia, which collectively are expected to produce systematic excess return unrelated to the basic stock and bond risk premiums. These second‐order risk premiums are undoubtedly much smaller, if they exist at all.

Potential investors in US middle market direct loans frequently question why middle market yield spreads are so high, particularly when the record shows that historical credit losses have been about the same as losses found in more liquid broadly syndicated loans (BSLs) and high‐yield bonds. Does the free‐lunch label apply to this new institutional asset class or is there something else going on?

Analysis of the direct loan database underlying the Cliffwater Direct Lending Index shows that middle market direct lending is a collection of yield spreads, each associated with a different risk factor and each risk factor is non‐diversifiable and deserving of a risk premium. This is very unlike investing in stocks, bonds, or liquid credit where there is one dominant factor receiving a risk premium. Instead, direct lending is a collage of risk premiums, each identifiable with consistent excess returns associated with each. Risk premium excess returns primarily take the form of excess income or yield in our analysis.

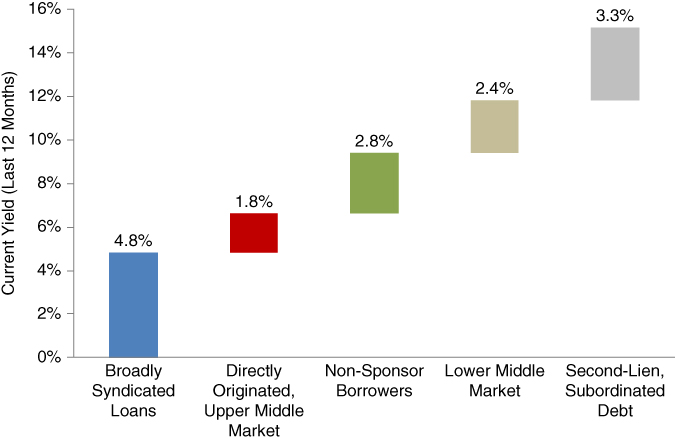

There are four identifiable risk premiums unique to middle market direct lending with quantifiable yield spreads associated with each one. Exhibit 9.1 reports yield spreads (premiums) available to the four risk factors found within middle market lending. The measurement date is December 31, 2017.

EXHIBIT 9.1 Available risk premiums in direct US middle market corporate loans, December 31, 2017.

The left‐most bar in Exhibit 9.1 is the yield available in BSLs, measured by the S&P/LSTA US Leveraged Loan Index, which equaled 4.8% as of December 31, 2017. The four bars to the right identify four additional yield spreads, each associated with a unique risk premium. Yield is defined as trailing 12‐month interest income. The four risk premiums are:

- Directly originated, upper middle market. There is a 1.8% yield premium for moving from liquid broadly syndicated bank loans to senior loans backed by upper middle market, sponsor‐driven borrowers. This yield premium can be interpreted as a liquidity premium because underlying loan characteristics are most like bank loans except for being privately originated as opposed to bank originated and broadly syndicated.

- Non‐sponsor borrowers. There exists a 2.8% yield premium for holding debt of companies not controlled by private equity firms, something that could be interpreted as a governance premium or non‐sponsor premium. Non‐sponsor borrowers might be viewed as riskier because management behavior, particularly under corporate distress, could be less predictable and costlier to lenders compared to sponsor‐backed borrowers.

- Lower middle market. A 2.4% yield premium is found for lending to lower middle market borrowers, companies with annual EBITDA less than $10 million, compared to upper middle market borrowers with EBITDA over $100 million. This could be a “size premium” often found in other asset classes.

- Second‐lien, subordinated debt. Not surprisingly, the largest yield premium is associated with the seniority subordination risk premium. Subordinated loans have a 3.3% higher yield when compared to senior loans within the US middle market.

Incremental yields for the four risk premiums have been stable over the past two years (eight quarters) of measurement. The one exception is the subordination risk premium for subordinated loans that has declined materially from 4.2% to 3.3%. This spread narrowing for middle market direct loans is consistent with declining spreads for junior and mezzanine debt in the broadly syndicated and structured credit markets. Investors should expect more stability in the first three risk premiums but some fluctuation in the subordination risk premium that is directly tied to the overall business and credit cycles.

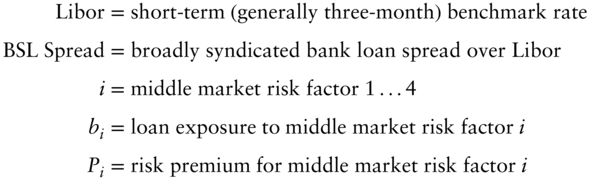

Understanding risk premiums is useful in both developing return expectations for direct loans and understanding past performance. Equation 9.1 illustrates how investors can use the risk premiums in combination with direct loan manager portfolio risk exposures.

Take, as example, a conservative manager whose focus is senior, sponsor‐based loans across the middle market and the middle market loan risk factors and premiums are the four described in Exhibit 9.1. The manager's beta ( ) exposure to the first factor, directly originated private corporate loans, equals 1.0, by definition, if the manager stays fully invested in direct loans. Our conservative manager wants the convenience of investing only with sponsor‐backed borrowers so the beta exposure to the non‐sponsored risk premium equals 0.0. The manager's exposure to the third lower middle market risk premium equals 0.5, because roughly one‐half the loans are upper middle market and the other one‐half are lower middle market. Finally, our conservative manager, by style, wants to remain in the senior part of the borrower's capital structure and therefore has a beta exposure to the subordinated risk premium equal to 0.0. Equation 9.2 calculates the expected yield for our conservative manager.

) exposure to the first factor, directly originated private corporate loans, equals 1.0, by definition, if the manager stays fully invested in direct loans. Our conservative manager wants the convenience of investing only with sponsor‐backed borrowers so the beta exposure to the non‐sponsored risk premium equals 0.0. The manager's exposure to the third lower middle market risk premium equals 0.5, because roughly one‐half the loans are upper middle market and the other one‐half are lower middle market. Finally, our conservative manager, by style, wants to remain in the senior part of the borrower's capital structure and therefore has a beta exposure to the subordinated risk premium equal to 0.0. Equation 9.2 calculates the expected yield for our conservative manager.

The 7.80% expected yield for this conservative manager, gross of fees, leverage, and credit losses, falls 2.36% below the 10.16% gross yield on the Cliffwater Direct Lending Index at December 31, 2017, as calculated in Equation 9.3.

The yield deficit for the conservative direct loan manager compared to the asset‐weighted average manager, which the CDLI mirrors, could be overcome by several factors so that actual total return performance, and risk, is competitive or superior to the average manager. For example, expected credit losses could be lower. A reasonable expectation is for a senior‐only manager to have realized credit losses that are 0.25% below the average manager represented by the CDLI, based upon differences in recovery rates for senior and subordinated debt. Second, expected fees for a senior‐only manager should be about 0.50% lower (including both asset‐based and incentive fees) and the nonsponsor focus for our conservative manager should lower fees another 0.10%. The lower fees for different risk‐factor exposures are covered in a later chapter. Investors could reasonably expect that a senior only, non‐sponsor lender might offer fees that are 0.60% (0.10% plus 0.50%) below the average direct lending fee. Third, the cost of borrowing to finance leverage should be lower for a senior‐only direct lending portfolio. Comparing financing costs for business development companies that invest in only senior debt shows an approximate 1.0% lower cost of financing for senior loan portfolios compared to the overall CDLI. The financing cost comparison is based upon a leverage ratio equal to approximately 0.6x net assets. Multiplying the 1.0% in lower borrowing costs with the 0.6x leverage level gives a net savings equal to 0.60%.

The likely net cost savings for our senior‐focused direct lending manager equals 1.45%, equal to the 0.25% savings from credit losses, the 0.60% savings on fees, and the 0.60% savings on financing costs. Deduction of these cost savings from the 2.36% gross yield spread still leaves a 0.91% yield disadvantage for our senior lender. However, other mitigating factors might first include the ability of the senior direct lender to use more leverage than the average manager and at lower financing costs. Senior‐only direct lending portfolios often can support an additional turn of leverage, which would alone be more than enough to close the remainder of the yield gap. There is one other point worth noting. Senior loans seldom have payments‐in‐kind (PIK) income. To the extent that PIK income is not valued as highly as cash interest, the 0.41% in PIK income earned the average manager might be viewed as a soft difference.

The risk premium model for middle market direct corporate loans described in Exhibit 9.1 is a useful construct in understanding where yield comes from and the risk factors underlying them. This understanding is very important in yield‐driven asset classes where investors are often mesmerized by the manager or fund with the highest yield, on the presumption that yield translates into realized return. Differences in fees, realized losses, and financing opportunities are direct mitigating factors that need to be considered when comparing yields, but so also is general risk‐taking, and each risk factor likely possesses incremental valuation risk (unrealized losses).

METHODOLOGY

The discovery of risk premiums in middle market loans is based upon data collected from public information disclosed by public and private BDCs and from private data sources.

Risk premiums are calculated through a cross‐sectional regression where the dependent variable is portfolio yield and the three independent variables are: expected/actual share of sponsor/non‐sponsor lending (measured by percentage allocations to sponsor or non‐sponsor lending); expected/actual portfolio company size (measured by average EBITDA); and loan seniority (measured by percentage allocations to senior or subordinated debt). The independent variables are scaled such that higher values represent higher expected risk (e.g., non‐sponsor borrower, smaller borrower, and more junior debt). By design, the intercept term is the yield on larger sized, sponsor‐backed, senior loans. The yield on a BSL, measured by the S&P/LSTA US Leveraged Loan Index yield, is subtracted from the intercept yield to separately capture what is interpreted as the liquidity premium.

The results from the regression's intercept and coefficients are the yield premiums reported in Exhibit 9.1. Each regression coefficient is statistically significant (T‐stat > 3.0) with an overall regression R‐squared equal to 75%.

Ideally, the identified risk premiums would be measured net, not gross, of credit losses. Useful further study would be an analysis on the relationship between risk premiums and credit losses, something that is currently challenging because it likely requires another downward credit cycle like the 2008–2010 period, when significant realized credit losses last occurred in middle market direct lending.

However, credit losses for two of the risk premiums seem fairly settled. The 1.8% current illiquidity premium is not offset by incremental credit losses. Credit losses on the CDLI have not been statistically different from credit losses on broadly syndicated bank loans, so the 1.8% yield spread should be viewed as both gross and net of credit losses. By comparison, evidence shows that the 3.3% yield spread for the subordination risk premium comes with incremental credit losses. There is plenty of data showing that subordinated debt experiences higher credit losses, primarily through lower recovery rates, when compared to senior debt.

That leaves questions around credit losses for sponsored versus non‐sponsored debt, and upper versus lower middle market debt. The author knows of no published study addressing the sponsor, non‐sponsor question. On the matter of upper versus lower middle market debt, a 2012 Moody's Analytics RiskCalc 4.0 study examining factors predictive of default, seven financial variables were found to be predictive of default frequency. The most important was the amount of debt as a percent of corporate assets. The least important factor was company size, measured by assets. At this time, it seems that the relationship between credit losses and non‐sponsor borrowers and smaller borrowers remains unanswered.

The presence of unique risk premiums in US middle market direct lending will be important in later chapters on asset managers. While all asset manager lenders have exposure to the illiquidity premium, exposures to non‐sponsor, lower middle market, and subordinated risk factors vary widely. This makes discriminating among asset manager lenders based only on yield very difficult, if not misleading, because of possible differences in risk‐taking. Investors often make the mistake of investing with asset managers or in funds with the highest yield. Risk‐adjusting portfolio yields is an important part of understanding manager performance and selection.