4 September 1960. Following a 5-1 home win over Peñarol Montevideo, Real Madrid lifts the first Intercontinental Cup. This new trophy brought together the winners of Europe’s and South America’s flagship club competitions: UEFA’s Champion Clubs’ Cup and the South American Football Confederation’s Copa Libertadores. It was an occasion on which continental allegiances prevailed, with some journalists seeing Real Madrid as representing the whole of Europe.1 Launching this event—the world’s first transcontinental competition for clubs—had required more than two years of negotiations between the two continental bodies,2 encouraged by L’Équipe.3 Moreover, the competition was planned entirely outside the confines of FIFA, which did not recognise it.4

The Intercontinental Cup is a good illustration of the changes in international football that had taken place over the past two decades. First, it shows how the creation of continental confederations during the 1950s had resulted in more structured links between the continents. Second, it highlights the continental confederations’ status as significant players in developing football, on their respective continents and more broadly around the world, where they compete with FIFA.

8.1 The Establishment of a European Football Confederation

In this book, I retrace the history of the founding of UEFA and show how it became a key player in developing the European scale in football. My research focused on three complementary themes: UEFA’s role in increasing football exchanges within Europe; the ability of UEFA’s leaders to create an organisation that transcended Cold War divisions; and the reasons why UEFA came into being in the mid-1950s.

My analysis of UEFA’s role in increasing football exchanges within Europe was based on the hypothesis that its creation corresponded to a new stage in this process. Although there had been regular football-related exchanges between European countries since the end of World War I, a new stage began in the late 1940s, initiated by the reintegration of the British associations and the affiliation of the Soviet Union into FIFA. This expansion of the ‘Europe of football’ inspired many of the game’s leading figures to launch more ambitious competitions and even to suggest creating a continental confederation. This latter idea was first reported in the French press in 1949 and attributed to Ottorino Barassi, the Italian FA’s influential president, but the conditions required to create such an entity did not emerge until 1953, when FIFA adopted a more decentralised structure. UEFA was founded the following year and immediately began taking steps that would increase exchanges within European football. Its efforts, which were primarily focused around creating new tournaments for national teams and clubs (e.g. European Cup of Nations and, later, the Cup Winners’ Cup) and taking over existing competitions (e.g. European Champion Clubs’ Cup, International Youth Tournament), successfully initiated new exchanges between national associations all across Europe, from Norway to Greece, from Turkey to Ireland. As well as becoming more numerous, European matches were now played throughout the football season, in contrast with the interwar competitions (such as the Mitropa Cup), which had been concentrated mostly into the summer months.

These developments were facilitated by improved transportation (including air travel, which enabled teams to play abroad during the week and be back in time to play in their domestic championship at the weekend) and stadium infrastructure (e.g. floodlighting, which allowed games to be played at night, even during the winter), but launching new competitions was not, of course, a linear process and some projects, notably the European Cup of Nations, were resisted by some influential national associations (England, Germany and Italy). Nevertheless, by the early 1960s there were more European matches than ever before, and some commentators were beginning to suggest that European tournaments had become at least as important as national and international competitions, albeit without eclipsing them entirely.

My second theme was how UEFA’s leaders managed to create an organisation that overcame Cold War divisions. This unique achievement set UEFA apart from the supposedly pan-European entities that were founded in other fields at this time (e.g. culture, economics, science, technology) but which did not go beyond Western Europe. My aim was to examine the relationship between UEFA’s ruling elite and politics, in order to determine how UEFA was able to bring together individuals, clubs and even nations that would otherwise have remained separated by international politics and, more generally, how it managed to maintain its autonomy on the international scene.

I found that in order to ensure their organisation’s independence from other international bodies, UEFA’s leaders applied similar governance strategies to those developed within FIFA since the 1930s, including gaining financial independence, not intervening in the affairs of its member associations, consulting the different forces within UEFA when filling seats on the executive committee and appointing leaders who had diplomatic skills (a sine qua non for the secretary general) and experience of how their respective national associations worked, but, if possible, who did not hold political office. All these decisions strengthened UEFA and enabled it to establish itself as the dominant body in European football and to be seen as such by other entities both inside and outside (e.g. other international organisations) the world of football.

I dwelt on these points at length in order to provide a clear explanation of how, from the very beginning, UEFA managed to get associations from both sides of the Iron Curtain to work together and how its leaders managed to limit the impact of the Cold War on the organisation. UEFA’s success in this respect, accomplished by applying similar conflict-avoidance strategies to those used by FIFA’s leaders, enabled it to grow rapidly and establish itself as the regulating body for European football. Thus, despite the potential for political discord between its members, by the end of the 1950s UEFA had obtained a monopoly over European football competitions and prevented other football bodies (e.g. the ILLC created in 1959) from launching European competitions. At the same time, organisations outside the world of sport (e.g. the European Broadcasting Union) had come to consider UEFA as the governing body for European football. However, UEFA’s rise was not universally welcomed, especially by FIFA, whose leaders were unhappy to see some of their responsibilities were being taken from them. Differences between UEFA and FIFA came to light over a wide variety of issues (e.g. UEFA’s takeover of the International Youth Tournament) and risked causing antagonism between the two organisations. In order to avoid this possibility, a FIFA-UEFA consultative committee was set up to discuss issues before they became problematic. Last but not least, UEFA’s competitions and annual congresses provided regular opportunities for official meetings between countries that otherwise had no diplomatic relations, such as Spain and Yugoslavia. This almost unique ability to bring countries together made UEFA an ‘atypical actor’ in the Europe integration process.

The third question I addressed in this book is why UEFA was created in the mid-1950s. Viewed from a global perspective, the primary factor governing the timing of UEFA’s formation can be seen to be the restructuring of FIFA along continental lines in 1953, which South America’s associations had been campaigning for since the 1930s. Strengthened by their alliance with the Central American associations, via the creation in 1946 of the Pan-American Confederation, in the late 1940s South America’s executives put forward concrete proposals to decentralise FIFA and thereby acquire additional seats on its executive committee. Their demands were given greater weight by Europe’s concerns about losing its dominant position within FIFA due to the number of newly decolonised African and Asian countries that started joining the world governing body after World War II.

This influx of new associations meant FIFA not only had to address South America’s demands, it had to take into account Africa’s desire to create a supra-regional grouping. These ideas resonated with the new generation of European leaders, notably Barassi, Rous and Thommen, who were becoming increasingly influential within FIFA and who believed that the federation needed to be restructured in order to develop football around the world. FIFA’s 1950 congress in Rio de Janeiro—the first congress to be held outside Europe—examined a variety of possible reforms to FIFA’s structure but decided that further consultation was needed. After three years of negotiations, a comprehensive proposal for restructuring FIFA was ready to present to an extraordinary congress in Paris in November 1953. Despite intense debate between the different blocs within FIFA (South American, British, Soviet), each of which had its own position, an alliance between the Western European and South American associations resulted in the extraordinary congress finally approving a formal motion to create continental groups. Under the new statutes, Europe’s associations were allocated six seats on FIFA’s executive committee and would therefore have to create a continental grouping to choose the people who would fill these seats.

Restructuring FIFA along continental lines, a reform it had been demanding for two decades was not the South American confederation’s only contribution; it also provided the model on which Europe’s leaders based the new European grouping’s organisational architecture when it was founded at the beginning of 1954. South America continued to influence UEFA throughout its early years, most notably when it was looking for new sources of income. Thus, in 1955 UEFA asked to receive a proportion of the revenues FIFA collects from international matches involving European teams, using as its main argument the similar agreement FIFA had already signed with the South American confederation. After several months of discussions, FIFA finally agreed to UEFA’s request.

However, UEFA developed so quickly during the 1950s that by the end of the decade, the roles had been reversed. Inspired by the success of UEFA’s Champion Clubs’ Cup, in 1959 the South American confederation approached FIFA for details of the European competition so it could study them before setting up its own continental club competition, the Copa Libertadores. It is noteworthy that the two confederations also conferred, and even formed alliances, within FIFA, as when UEFA asked FIFA to redistribute to the confederations a proportion of the revenues it earned from World Cup matches.

By the end of the 1950s, UEFA had a well-established structure and was starting to be recognised as the governing body for European football. It would consolidate this position throughout the coming decade.

8.2 UEFA’s Consolidation during the 1960s

The early 1960s gave UEFA the opportunity to extend its territory by affiliating three new members: Malta, in 1960; Turkey, in 1962; and Cyprus, in 1963.5 As discussed in Chapter 6, the Turkish FA had been refused UEFA membership in 1954, notably because it was based in Ankara, on the Asian side of the Bosporus, and therefore considered by FIFA to be an Asian association. This changed in the early 1960s, when the Turkish FA moved its headquarters to Istanbul, on the western side of the Bosporus, enabling FIFA to recategorise it as European. The door was now open for it to join UEFA.6 These three arrivals increased UEFA’s membership to 33 associations, a number that would remain unchanged until the early 1990s, when the fall of the Iron Curtain and the resulting break-up of both the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia redrew the political boundaries within Eastern Europe.

Number of countries and delegates present at UEFA congresses from 1960 to 1970

Congress venue | Year | Parallel events | Countries present | Delegates presenta |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Rome | 1960 | Olympic Games | 29 | 80 |

Londonb | 1961 | FIFA Congress | 29 | 81 |

Sofia | 1962 | – | 30 | 67 |

Madrid | 1964c | – | 30 | 71 |

London | 1966 | World Cup (FIFA Congress) | 32 | 89 |

Rome | 1968 | – | 32 | 92 |

Dubrovnik | 1970 | – | 32 | 79 |

UEFA had achieved its dominant position in European football primarily by securing a monopoly over European competitions. It is also important to note that clubs from the Soviet Union finally began taking part in UEFA’s club competitions in 1966 (Zeller 2011). This shows how important UEFA’s tournaments had become for UEFA’s members and clubs and also the importance the Soviet Union government accorded to international sport exchanges (Dufraisse 2020). However, other organisations (e.g. the International League Liaison Committee, see Chapter 6) continued putting forward ideas for ambitious new tournaments with the potential to rival UEFA’s competitions and challenge its monopoly. Two such proposals came to UEFA’s attention in the mid-1960s, nearly a decade after a group of journalists at L’Equipe had launched Europe’s first club competition, the Champion Clubs’ Cup. The first of these proposals, the ‘Télé-magazine Cup’, was dreamed up by the French newspaper proprietor and president of Olympique de Marseille football club, Marcel Leclerc, who planned to use television to popularise the event (Vonnard 2019b). The second project was devised by the European Economic Community’s (EEC) press office. Involving the eight clubs (one from each of the Common Market’s six member countries, plus one English and one Scottish club) that finished second in their domestic leagues, it was conceived as a counterpart to the Champion Clubs’ Cup (Vonnard 2018b). Neither project went ahead, but they show that many organisations, both inside and outside football, were interested in launching new European competitions. In a similar vein, several major European clubs held meetings in Monaco in 1967 in order to discuss issues such as reforming European football competitions and resurrecting the old idea (first put forward in the 1930s by journalists, including Gabriel Hanot) of creating a European club championship (King 2004)—an idea that is still in the air and regularly resurfaces in the media.

None of these ideas came to fruition, largely because of the measures UEFA’s executive committee took to counter them, including reserving the sole right to organise European tournaments and prohibiting ‘clubs participating in UEFA competitions from taking part in other international club competitions’.7 Although this clause did not ‘apply to club competitions held exclusively during summer breaks’,8 it undeniably made UEFA’s competitions more attractive. Nevertheless, UEFA’s monopoly over major European competitions was not complete, as the Inter-Cities Fairs Cup remained out of its control. Some member associations felt UEFA should take over the competition and called on the executive committee to do so in 1962.9 Although the UEFA’s leaders rejected this request, preferring just to have a say in the event’s rules, the tournament’s continued success soon led them to change their minds. In fact, by the mid-1960s the Fairs Cup had become Europe’s largest football competition in terms of the number of clubs taking part (almost 60 clubs) and was therefore a threat to UEFA’s dominant position in European competitions (Ferran 1978). UEFA’s 1966 congress readily approved a motion to take over the competition,10 but five years of negotiations were needed before this decision came into effect, in 1971. UEFA marked this change by renaming the event the ‘UEFA Cup’.11

UEFA’s three European competitions, which journalists began calling the ‘European Cups’, received extensive media coverage (press, radio, television) and impacted Europe’s football stage in two main ways. First, by awarding places in European competitions to only the top three or four clubs in each country’s domestic league, they intensified national championship battles. Second, they gave great status to clubs capable of winning them and turned some teams (e.g. Real Madrid in the 1950s, Ajax Amsterdam, Bayern Munich and Liverpool FC in the 1970s) or players into legends (Holt et al. 1996). The prestige and financial windfall clubs derived from UEFA’s competitions meant it was difficult to set up other tournaments that would be played at the same time of year. For this reason, most new tournaments, such as the International Cup (also known as the Intertoto Cup or the Karl Rappan Cup), created in 1960 by sports betting groups, and the Balkan Club Cup (Breuil and Constantin 2015), took place during the summer break.12

In the mid-1960s, UEFA decided to reform the European Cup of Nations and rename it the ‘European Championship of Nations–Henri Delaunay Cup’, in memory of UEFA’s first secretary general. Instead of the two-leg, knockout format of the 1960 and 1964 editions, the revamped competition would take the form of a mini-championship in which the first three rounds (round of 32, round of 16 and quarter-finals) of the original competition were replaced by a qualifying phase played in groups of three to four teams. The new format increased the number of matches that would be played, as did the inclusion, for the first time, of all of Europe’s football associations, including the British and German associations (Dietschy 2017). A similar process happened to the International Youth Tournament with the consequences to reinforce the competitional aspect of the competition to the detriment of the educational aspect wanted by its initial promoters (Marston 2016b).

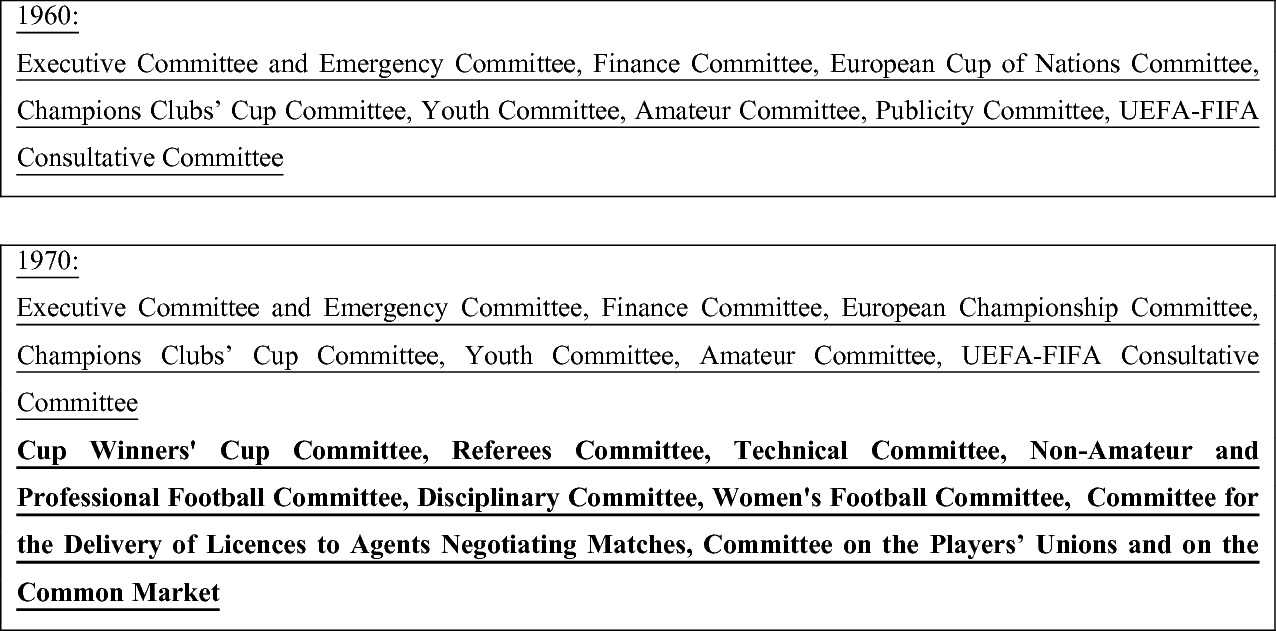

Comparison of UEFA’s main standing committees in 1960 and 1970

(Note In bold—committees created after 1960. Source Compiled from the UEFA secretary general’s annual reports. Here, I have noted included the Disciplinary commission and Appeal Jury of the competitions)

Realising it needed to evolve to keep pace with its expansion, in 1962 UEFA adopted a new set of statutes, whose 33 articles were presented in a highly professional, 15-page document that included a table of contents and bore the date and the signatures of UEFA’s president and secretary general. UEFA now had 13 ‘missions’,14 including bringing European associations together, administrating competitions, representing European football in FIFA, and organising training courses (e.g. for referees). These new statutes clearly show UEFA’s leaders’ intention to pursue a range of initiatives to develop European football.

It is important not to underestimate the role these personal contacts play in ensuring good relations between associations. This event also provides an opportunity for the associations to discuss many unresolved issues on a face-to-face basis, thus eliminating potential misunderstandings.16

UEFA also strengthened its position as the voice of European football within FIFA, which had adopted the format of UEFA’s tournaments when it began launching its own competitions for clubs and nations. FIFA also took UEFA as a model for its relations with the other continental confederations when it set up a series of consultative committees similar to the one it had established with UEFA in 1959. In fact, this period saw all the confederations gradually assert themselves within FIFA, sometimes in concert, sometimes separately. For example, UEFA worked with the South American confederation to coordinate the Intercontinental Cup, even though FIFA had not authorised the competition, but clashed with the Confederation of African Football over the number of World Cup places (Darby 2019) and FIFA executive committee seats (Dietschy and Keimo-Kembou 2008; Nicolas and Vonnard 2019) allotted to each continent. These disagreements, coupled with other grievances against FIFA’s European president Stanley Rous, notably his refusal to support the exclusion of the South African FA (Darby 2008; Rofe and Tomlinson 2019), had a significant impact and led FIFA to elect its first non-European president, Brazil’s João Havelange, in 1974 (Dietschy 2013; Vonnard and Sbetti 2018).

In 1962, UEFA’s congress chose Switzerland’s Gustav Wiederkehr to take over as the organisation’s president.17 Wiederkehr, together with Belgium’s José Crahay, Hungary’s Sandor Barcs and UEFA’s Swiss general secretary, Hans Bangerter, was part of a new generation of executives that rose to the top of European football in the 1960s. They were later joined on the executive committee by men such as Italy’s Artemio Franchi and Czechoslovakia’s Vaclav Jira, who contributed greatly to UEFA’s development. Franchi and Jira also embodied UEFA’s growing independence from FIFA, because, from now on, not all members of UEFA’s executive committee had served on FIFA’s executive committee and most of them had not held positions on any of its permanent committees. Being relatively detached from FIFA meant that protecting UEFA’s interests within the world of international sport was the new leaders’ top priority and this increased the executive committee’s cohesion. In addition, some executive committee members were also secretaries of their national association and this gave them a more ‘technical’ view of football. Hence, their focus was to develop the sport, especially at the professional level, in contrast to FIFA’s ruling elite, who saw football’s contribution in more ‘societal’ terms.18

Members of UEFA’s executive committee in 1966

Name | Nationality | Position in the national associationa | First participation at a UEFA congressb | First year in office (UEFA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Crahay J. | Belgian | Secretary | 1955 | 1955 |

Pujol A. | Spanish | Secretary | 1956 | 1956 |

Brunt L. | Dutch | Secretary | 1955 | 1960 |

Barcs S. | Hungarian | President | 1956 | 1962 |

Bangerter H. | Swiss | None | 1960 | 1960 |

Powell H. | Welsh | Secretary | 1955 | 1962 |

Wiederkehr G. | Swiss | President | 1955 | 1962 |

Eckholm T. | Finnish | Secretary | 1955 | 1962 |

Gösmann H. | West German | President | 1960 | 1964 |

Pasquale G. | Italian | President | 1960 | 1964 |

Wiederkehr, supported by UEFA’s secretary general, Hans Bangerter, pursued a policy of building harmony between Europe’s associations, which were divided on certain issues by Cold War politics. Despite making strenuous efforts to overcome these divisions since its very beginnings (Mittag and Vonnard 2017), there was still tension between the Eastern and Western blocs within UEFA. Consequently, a major component of Wiederkehr’s policy throughout the 1960s was to increase the Eastern bloc’s participation in UEFA’s affairs, which he did by holding congresses in Sofia, in 1962, and in Dubrovnik, in 1970 (Mittag 2015), hiring an Eastern European deputy secretary (Michel Daphinov, from Bulgaria) in 1962,20 and ensuring the secretariat’s staff covered the languages needed to interact with most of UEFA’s member associations.

Nevertheless, the East-West divide weakened UEFA’s efforts to achieve what Wiederkehr and his colleagues considered a key goal—reforming FIFA’s electoral system by replacing the one member-one vote system with a proportional system. UEFA’s aim was to protect its position within a world governing body whose membership was growing rapidly thanks to the affiliation of the newly independent African and Asian countries produced by decolonisation, which were now eligible to join FIFA. As a result, of the 126 member associations listed in the 1965 FIFA Handbook, only 33 were European.

As scholars have already noted (Sugden and Tomlinson 1998; Broda 2017), UEFA’s failure to obtain this reform was largely due to opposition from the African confederation (Darby 2008), although its case had not been helped by the lack of consensus among UEFA’s members. Most importantly, the Soviet bloc refused to endorse the proportional voting system for reasons that were both ideological—they saw the proposed system as a way for Western Europe to continue its colonialist domination—and strategic—opposing proportional voting would help them increase their influence over FIFA’s governance by allowing them to forge alliances with countries of Africa. This policy, which the Soviet bloc also pursued within the IOC (Charitas 2009; Parks 2014; Dufraisse 2020), meant Europe was unable to present a unified front on the voting issue.

The differences between UEFA’s members tended to come to the fore when international tension was high, and Hans Bangerter told me that he had had ‘huge problems from a political point of view’ during the 1960s.21 For example, following the construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961, East German teams were often denied visas to compete in countries outside the Eastern bloc (e.g. Dichter 2014, McDougall 2015; Kalthof 2019). Another problem of geopolitical nature arose in September 1968, when most of the Soviet bloc (except Romania and Czechoslovakia) withdrew from European club competitions in protest against UEFA’s decision to reduce the number of matches between East and West.22 More positively, the speed with which this issue was resolved highlighted sport’s openness to diplomacy (e.g. Frank 2012; Rofe 2018; Clastres, 2020), and Soviet bloc teams once again took part in the competitions during the 1969–1970 season. In fact, UEFA’s leaders used numerous initiatives to limit the impact of international politics on European football. For example, in order to avoid problems with visas, it divided the draw for the European Cup of Nations into geographical groups, so, in the 1964 edition, East Germany only played teams from the Eastern bloc. Such strategies, combined with the long tradition of football exchanges across Europe, helped UEFA build bridges between East and West throughout the Cold War.23

In addition to these geopolitical differences, there was also discord within UEFA on how the organisation should be administered. As early as 1962, disagreement over the attribution of seats on the organisation’s executive committee led the Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, French, Belgian, Dutch and Luxembourg FAs to form a bloc capable of negotiating with the other two groups within UEFA (Breuil 2016, p. 126; Dietschy 2020b, p. 30 ), that is, the Soviet bloc, and a bloc consisting of the British and Scandinavian associations. The Florence Entente, as the group came to be known, was a true pressure group that recorded its actions and had a secretariat.24

Despite these tensions, UEFA managed to reinforce its position as the governing body for European football and to become recognised as such both within football and beyond. One of UEFA’s most important partners outside football was the EBU, to which it sold the rights to televise the finals of the Champion Clubs’ Cup and the Cup Winners’ Cup. In 1968, after several years of negotiations, the two bodies signed an agreement that valued the television rights to these two matches at 1 million Swiss francs. This was a very large sum at the time and corresponded to almost half of UEFA’s contingency fund (Vonnard and Laborie 2019, p. 120). According to my estimates (and therefore to be treated with caution), in the late 1960s UEFA earned between 60 and 70% of its annual income from the television rights to its matches.

UEFA also had extensive dealings with the EEC, especially over the issue of football transfers, as its rules did not comply with the provisions of the 1957 Treaty of Rome on the free movement of workers (Schotté 2016).25 After a long series of negotiations, begun at the end of the 1960s, the EEC and UEFA reached a gentleman’s agreement under which football was allowed to keep its special status. This agreement was renegotiated on several occasions but remained in place until 1995, when it was overturned by the Bosman ruling.26

By the early 1970s, UEFA had achieved a very solid position. More generally, European-level football, which, as this book shows, had developed thanks largely to UEFA’s efforts, was well established. Consequently, although there were still calls to modify certain things (e.g. the format of competitions), debate over the desirability of European exchanges had virtually died out. Hence, at the very moment when important advances were being made in East-West cooperation, exemplified by the signature of the Helsinki Accords at the 1975 Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe, UEFA’s European Champion Clubs’ Cup, which was broadcast live to a great many European countries, was already celebrating its 20th anniversary!

8.3 Further Researches on the Europeanisation of Football History

Hence, the actions of UEFA’s executive committee ensured the continuation of football exchanges between countries from different parts of Europe and undeniably played a key role in making such exchanges an integral part of the continent’s football landscape. Further research into the history of UEFA is now needed, especially with respect to the 1960s and 1980s. Recent work, most notably by Manuel Schotté (2014) and William Gasparini (2017), has shown that European football exchanges increased during this period, which contradicts a Anthony King’s finding that it was a period of eurosclerosis (2004).27 In fact, it was during these decades that the seeds were sown for the major transformations in European football of the 1990s and 2000s. More clarification should in the future be provided by in-depth studies of the pressure put by leading European clubs on UEFA with the aim of creating a European club championship—often referred to as ‘Superleague’—and which resulted in the compromise of transforming the Champion Clubs’ Cup being into the Champions League in the early 1990s (Holt 2007, Olsson 2011 pp. 21–24). Other areas worthy of further research include UEFA’s structure, the profiles of its main leaders (Schotté 2014) and the organisation’s administration (Tonnerre, Vonnard, and Sbetti 2019), as the arrival of individuals with training in business and a stronger focus on developing the commercial side of football has led to substantial changes within UEFA.

Looking more closely at the 1970s and 1980s would help (re)connect the work of sport historians with that of political scientists, who have analysed the recent Europeanisation of the game (e.g. Niemann et al. 2011), and sociologists, who have examined the different actors that make up the ‘European soccer space’ (Gasparini and Polo 2012).

As stated in the introduction, one of this book’s aims is to extend the scope of research into the history of European cooperation, which has tended to focus on the Brussels-based EEC or EU. The insights provided by studying UEFA’s conception and early development confirm that the history of ‘European cooperation’ was not confined solely to the work of these entities (Warlouzet 2014).28 When Bernard Hozé (2003) wondered whether the sports movement had a vision of Europe, his verdict was rather negative. However, the present research argues against this conclusion and suggests that analysing the (many) instances of European cooperation in sport will bring to light the countless—and still unknown—exchanges that take place across the continent. Hence, further research is needed in order to understand the true place of football, and of sport in general,29 in the history of European cooperation.

This will mainly require examining two further, complementary, issues. First, a focus should be laid on the ambitions, objectives and agenda of European football leaders, especially with regard to their attitudes and connections with the European political integration process. This kind of research would tie in well with the reflection led notably by French scholars about European business owners (e.g. Cohen et al. 2007; Aldrin and Dakowska 2011). Secondly, and from a relational perspective (Patel 2013; Kaiser and Patel 2018), it would be interesting to study the consequences on European integration of the links UEFA formed with other European organisations (e.g. the EEC, the Council of Europe, for the 2000s see Garcia 2007; Gasparini and Heidmann 2011). Such an approach would provide new empirical evidence for what the historian Gérard Bossuat called the ‘space of inter-European relations’ (2012, p. 664), in which the role of sports is still underestimated. In addition, these studies would prove the potential for research into sport to make valuable contributions to our understanding of the history of European cooperations (Mittag 2018).

As the different studies conducted by the FREE project have repeatedly confirmed (Sonntag 2015), football can undoubtedly be included in the long list of areas that have become highly Europeanised over recent decades and which are of interest and relevance to Europe’s citizens in their daily lives (e.g. Badenoch and Fickers 2010; Bouvier and Laborie 2017). However, at a time when the very existence of a European Union is being questioned, it is essential to highlight the numerous links between Europeans and thereby challenge the oversimplified, often demagogic, discourse against European unity, which exaggerates differences and increases self-centredness and thereby risks once again propelling the continent into the abyss of ethnocentric nationalism. Moreover, and somewhat paradoxically given that many observers perceive football to be a catalyst of nationalism, a cause of violence or even the opium of the people,30 studying European football reveals the many forms of cooperation, which are often unknown or simply overlooked, that have existed among Europeans for decades (for a discussion: Vonnard and Marston 2020).

Thus, I would argue that football made it possible for several generations of football followers to learn about Europe’s geography, with European matches offering opportunities to travel, whether physically or by proxy through the media. Therefore, football brings this Europe to life by transcending barriers of social and cultural status, gender, age, nationality and, especially, language. While Albert Camus claimed to have understood a lot about morality through football,31 football has certainly taught Europe’s inhabitants a lot about the continent in which they live, and, according to an interesting study by Pierre-Edouard Weill, UEFA is today for many young people a better-known organisation than the European Union itself (2011).

Such a remarkable name recognition and positioning also entail a significant responsibility for UEFA in remaining truthful to the heritage of its own founders. Their goals of creating a ‘united continent’ and ‘leading by example’, as Ernst Thommen reminded the attendants of the UEFA’s founding congress in his inaugural address, are as important today as they were when the continent was still divided along the geopolitical fault lines. It is all the more important to be aware of the long and difficult journey that allowed UEFA to come into being in the first place, and this book has been nothing else than a modest attempt to contribute to this awareness, especially at a time when new, pending, reforms (notably concerning European clubs’ competitions) may lead to a new, potentially disruptive, turning point in the Europeanisation of the game.32