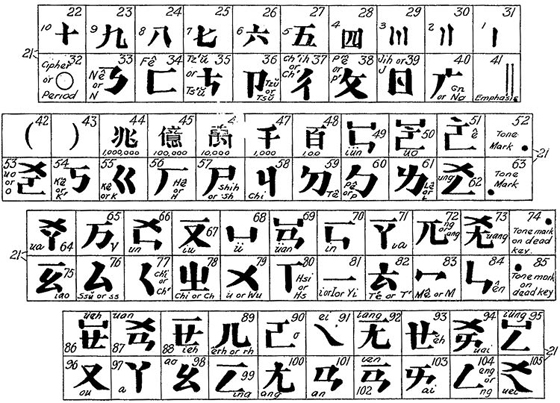

4.1 Shu-style Chinese typewriter, Huntington Library

The Chinese typewriter manufactured by the Commercial Press solves a serious problem in office administration in China. The machine has all the advantages of a foreign typewriter.

—Brochure for the Shu-style Chinese typewriter at the 1926 Philadelphia world’s fair

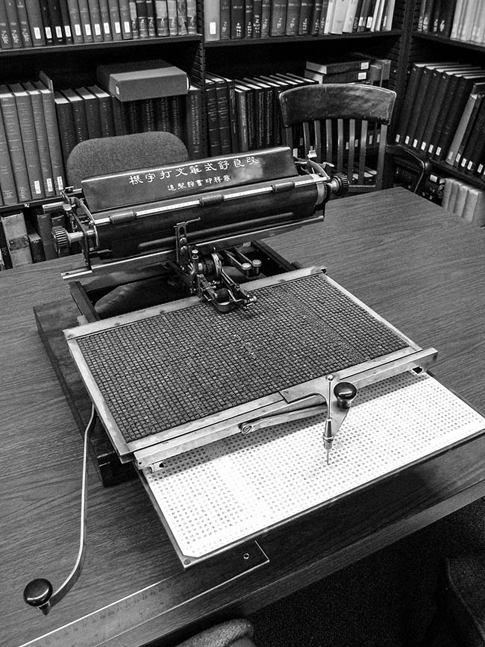

With its more than one hundred acres of botanical gardens, the Huntington in San Marino, California, transports hundreds of thousands of visitors each year into an otherworldly terrain populated by the Mexican Twin-Spined Cactus and the South American Heart of Flame. Inside, the library and museum draw scholars from around the world thanks to a world-renowned collection of rare books and artifacts on the American West, the history of science, and a range of other subjects. The Huntington also enjoys a rare distinction that few people are aware of: it is home to one of the oldest surviving Chinese typewriters in the world, the “Shu-style Chinese typewriter” manufactured by Commercial Press in Shanghai in the 1920s and 1930s (figure 4.1).

4.1 Shu-style Chinese typewriter, Huntington Library

The machine belonged to You Chung (Y.C.) Hong (1898–1977), a Chinese-American immigration attorney who served the Los Angeles Chinatown community. Establishing design patterns that would be followed by all mass-manufactured Chinese typewriters in history, it was a “common usage” machine featuring a rectangular tray bed containing approximately 2,500 character slugs. As in movable type printing, these character slugs were not fixed to the machine, but rather free-floating. If one were to remove a Chinese typewriter tray bed and turn it over, that is, the characters would spill out onto the floor, “pieing the type.”1 And, as with every Chinese typewriter ever mass-manufactured, it was a typewriter with no keyboard and no keys.

The tray bed of the Shu-style machine was divided into three zones based upon the relative frequency of characters: a zone of highest-usage characters, located centrally on the tray bed in columns sixteen through fifty-one; secondary usage characters, located on the right and left flanks of the tray bed, in columns one through fifteen and fifty-six through sixty-seven; and special usage characters, limited to columns fifty-two through fifty-five. Less commonly used characters, referred to as beiyongzi, were placed in a separate wooden box, a kind of lexical storage facility from which the typist could select characters and place them temporarily in his or her tray bed using tweezers. In this wooden case were housed approximately 5,700 additional characters.2

By the time of my visit in 2010, the characters on the tray bed of the Huntington Library’s specimen had long since rotted, exhibiting the consistency of weathered graphite or limestone. They had become so fragile, in fact, that when a curator demonstrated the typing mechanism to me, the gear accidentally shattered the faces of three of them. As for the characters located in the box of “lower-usage characters,” these had simply fused together into a mass of gray.

Even in this aged condition, though, the machine still bore the signature of what had clearly been a deeply personal relationship between the device, the typist who used it, and the man in whose employ this typist worked. As I moved around the machine, shifting my angle of view, fleeting constellations emerged from out of the brittle, charcoal-colored mass—shimmers of characters exhibiting greater reflectivity than their neighbors on account of being replaced more recently, likely because they had been used more frequently when the machine was still in service. Shifting to my right, and leaning toward the machine, the first shimmer of characters came to light: qiao (僑 “emigrant”), yuan (遠 “far away, distant”), and ji (急 “urgent”). With a slight adjustment of my orientation this first constellation melted back into the charcoal bath, and a second constellation came into view: zao (遭 “to encounter hardship”), xi (希 “to hope for, long for”), and meng (夢 “dream, to dream”). Each of these constellations was accompanied by more commonplace terms as well: yi (一 “one”), bu (不 “no, not”), shang (上 “atop”), and qu (去 “to go”). Not unexpectedly, one of the crispest characters on the tray bed was hong (洪), Y.C. Hong’s surname. Traces of the life this machine had lived still lingered, even decades later.

In this chapter, we leave behind the technical blueprints of inventors, linguists, and engineers, and explore instead the lived histories of Chinese typewriting. The Chinese typewriters in this chapter will not be prototypes nor the illusions of foreign cartoonists, but fully formed commodities that companies manufactured and marketed, that schools and training institutes explained and taught, and that typists used in the course of their careers. We will focus on the many worlds of the machine during the early twentieth century, from the advent of its mass manufacture at the Shanghai-based Commercial Press—the preeminent center of print capitalism in Republican China3—through the proliferation of Chinese typewriting schools in which young women and men studied this new technology and later employed it in a widening arena of government offices, banks, private companies, colleges, and even elementary schools. It is here that we will strain to see and hear the Chinese typewriter within its own linguistic context, attending to a history all but drowned out by the clichés of China’s technolinguistic backwardness we have examined thus far.

Even as we begin to observe the Chinese typewriter in these more local-level and intimate contexts, however, at no point will we find it entirely “at home” or in its “natural habitat.” Even with its unique mechanical design, its training regimens, its type and extent of usage, the gender makeup of the clerical workforce who used it, and the iconography and culture of the machine itself, at no point would either the Commercial Press machine or its later competitors ever have constituted the stable, accepted “counterpart” or “equivalent” of the Western machine—although not for lack of trying. Throughout the period, manufacturers, inventors, and language reformers alike remained acutely aware that the Chinese typewriter was at all times being measured against the “true” typewriter: the machines of Remington, Underwood, Olympia, and Olivetti, which steadily strengthened their hegemonic grip across the globe. Perhaps if the Chinese typewriter had never been conceptualized as a “typewriter” in the first place—if, instead, it had been described as a “tabletop movable type inscription machine,” or as some other niche apparatus disconnected from the larger, global history of modern information—constant comparisons between it and the “real” typewriter might never have been invoked. But this did not happen: the machine was a daziji—a typewriter—and by consequence was inescapably enmeshed within this broader, global framework.

During this period, the tensions between the Chinese typewriter and the “real” typewriter were pronounced. To function and make headway in the Chinese-language environments of government, business, and education, the Chinese typewriter would need to attend completely to the real-world necessities and practicalities of the Chinese language itself—and yet, as a “typewriter,” it would need to be legible to an outside world wherein resided the sole authority to decide which machines did or did not merit this title. The Chinese typewriter, and Chinese linguistic modernity more broadly, were thus caught between two impossibilities: to mimic the technolinguistic modernity that was taking shape in the alphabetic world, or to declare complete independence of this world and set out on a path of technolinguistic autarky. With neither option being feasible, Chinese linguistic modernity was caught irresolvably between mimesis and alterity.

Following the debut of his prototype, and particularly after he took up his position within Commercial Press in Shanghai, Zhou Houkun enjoyed a modicum of celebrity. On July 3, 1916, he demonstrated his machine at the Chinese Railway Institute in Shanghai, one of his first appearances as a representative of Commercial Press.4 Weeks later, Zhou continued his demonstrations at the Jiangsu Province Education Committee Summer Supplementary School, where the young engineer was praised for creating a machine that would print 2,000 characters each hour, rather than the 3,000 per day achievable by hand.5

Commercial Press remained hesitant about bringing Zhou’s device into production, however. While no sources clearly identify the reasons for this equivocation, one factor was undoubtedly the design of the apparatus itself. As examined in chapter 3, Zhou Houkun’s common usage machine featured a cylindrical character matrix upon which were etched Chinese characters in permanent and unchangeable form. In stark contrast to common usage as it functioned within its original context of typesetting, or even the earlier Chinese typewriter designed by Devello Sheffield, the characters on Zhou’s machine were completely fixed—impossible to adjust to different terminological needs and contexts. This posed a problem. As examined in the preceding chapter, there had been some hope that the tension within common usage might be resolved—at least for the Chinese masses—by means of promoting greater usage of “foundational character” sets within the contexts of both formal and informal education. If mass literacy could be achieved by statistically determining a limited set of characters that people needed to know, or would tend to employ, then in theory it might be possible to design a “foundational” Chinese typewriter tray bed to form a perfect fit with this mass vocabulary. For specialists and professionals, however, a fixed set of 2,500 characters would never be enough. For those working in banks, police stations, or government ministries, day-to-day language varied widely, which meant that Zhou Houkun’s original, unchangeable design would inevitably limit the device’s utility. To transform the common usage model into a workable technolinguistic solution for Chinese typewriting demanded that these devices offer up a measure of flexibility and customizability.

As early as winter 1917, relations between Zhou and Commercial Press began to sour, with the engineer and his corporate patrons drifting in separate directions.6 Zhou proposed a visit to the United States, where he hoped to inspect American typewriter production and develop an improved version of his machine to better suit the needs of potential customers. Zhou offered to cover the cost of his own travel, but requested that Commercial Press commit to providing the cost of manufacturing an improved machine he planned to complete upon his return. Zhang Yuanji declined, calling the financial commitment untenable. Zhou countered, offering to cover all expenses himself, but requesting that Commercial Press agree to sell and distribute the machine on his behalf. This offer was rebuffed as well. “I sense that it would be best for us to cancel our old contract,” Zhang recommended to his associates at the press, “and that [Zhou] handle everything on his own from here on out.”7 Thus came to an end Zhou Houkun’s brief relationship with Commercial Press, as well as his long-held dream of being the first to design a commercially successful typewriter for the Chinese language. In the years to come, Zhou returned to his first love of airplane and ship construction, to serve his country by other means.8 Circa 1923, he went on to join the Hanyeping Steel Company as their director of technology.9 Meanwhile, by May 1919, Commercial Press was in possession of Zhou Houkun’s prototype, but had not pursued plans of production.10

Commercial Press may have lost interest in Zhou Houkun, but not in the cause of Chinese typewriting. The company launched a Chinese typewriting class in 1918, further demonstrating its commitment to the new technology.11 After Zhou’s departure, more importantly, the company continued its pursuit under the guidance of another engineer: Shu Changyu, who would come to be known by his pen name, Shu Zhendong. Having studied steam-powered machines, and made forays at both the Maschinenfabrik Augsburg-Nürnberg (MAN) factory in Germany and the Hanyang factory in China, Shu joined the company circa 1919, receiving his first Chinese typewriter patent in the same year.12

One of the first steps Shu took was to abandon the Chinese character cylinder in Zhou’s original design. Shu replaced it with a flat, rectangular bed within which character slugs would sit loosely and interchangeably. With this change, the common usage machine would still be outfitted with the same number of characters as before, but now typists would be able to customize their machines to fit different terminological demands—as had been possible on Sheffield’s first prototype decades earlier. As free-floating metal slugs, characters could be removed and replaced using nothing more complicated than a pair of tweezers.

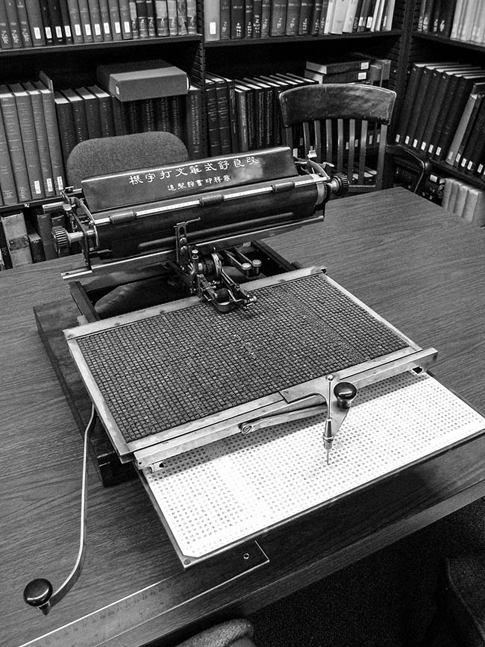

Following this important change in design, Commercial Press’s hesitation evaporated. The company dedicated a substantial financial investment to its new Chinese typewriter division, which occupied a reported forty rooms. Employing more than three hundred workers, and entailing some two hundred pieces of equipment, the process of building the new machine was divided among a variety of roles: melting lead to be used for character slugs, casting the character slugs, error-checking the tray bed character table, fitting the machine chassis, setting character slugs in their designated locations on the tray bed, and more (figure 4.2).13 If Bi Sheng had invented movable type nearly one millennium earlier, Shu Zhendong and Commercial Press now set out to manufacture a movable typewriter (figure 4.3).14

4.2 Roles and tasks in Commercial Press typewriter manufacturing plant

4.3 Commercial Press typewriter manufacturing plant

China’s first-ever animated film was entitled “The Shu Zhendong Chinese Typewriter,” and it was an advertisement for the new Commercial Press machine—the first mass-produced Chinese typewriter in history.15 Released in the 1920s, the film was produced by Wan Guchan and Wan Laiming, foundational figures in the early history of Chinese animation.16 The film is no longer extant, unfortunately, and yet a plethora of promotional materials from the era help us speculate as to its content. “It is said that the fastest speed is 2,000-plus characters per hour,” one article in 1927 read, “or three times faster than writing by hand.”17 Claims such as these focused on three merits of the machine in particular. First, it saved time as compared to composing a manuscript. Second, it produced more legible characters than did writing by hand. Finally, and most importantly, it could be used in concert with carbon-infused paper to produce multiple copies of a single document.

Song Mingde, Commercial Press employee and one-time head of the company’s Chinese typewriter division, placed particular emphasis on the machine’s function within textual reproduction, situating the device within the longue durée narrative of Chinese writing. In the time of Cang Jie, Song explained, paying homage to the apocryphal inventor of Chinese characters, Chinese writing had been limited to strictly ideographic forms carved upon the surface of bamboo. With the invention of the brush and paper, Song continued, this rendered it possible to “copy and record by hand” (yong shou chaolu). “Compared to bamboo, this was already ten thousand times more convenient.” From here, Song leapt over a large expanse of history to praise the third central invention within his abbreviated history, the printing machine (yinshuaji). With the advent of printing technology, he explained, the reproduction of many tens of thousands of copies was now well within reach.18

This leap from manuscript to mass reproduction had left behind a vast gap, however. Printing press equipment was expensive, Song emphasized, and required extensive preparation before usage, justifiable only in cases when large quantities of material were required. Still unresolved was the problem of smaller-scale, day-to-day textual reproduction of the sort required by modern businesses, whether in the form of short-run reports, office memos, or legal record-keeping. In cases when only 10 or even 100 copies were called for, the printing press was hardly an option. But neither were handwritten documents an attractive alternative, Song argued, since they “took time” (feishi) and were “irregular” (bu zhengqi).

Commercial Press thus advanced its typewriter as part competitor, part complement to both the human hand and the printing press.19 Early signs of commercial interest were encouraging, moreover. In his diary entry from April 16, 1920, Zhang Yuanji made note of a potential order from the Chinese postal division for one hundred machines.20 By 1925, Chinese consulates as far away as Canada were reported to have purchased a typewriter for their affairs.21 In 1926, Huadong Machinery Factory listed the Chinese typewriter as one of its best-selling and most widely known products.22 Commercial Press sold upward of two thousand units between 1917 and 1934, for an average of roughly one hundred per year. Commercial Press, in turn, attempted to raise awareness of the machine, not only by creating its pioneering animated film, but also by providing extensive demonstrations. In November 1921, Tang Chongli of Commercial Press included the Shu Zhendong machine as part of a demonstration of new technology and machinery by the Department of Forestry and Agriculture.23 On May 3, 1924, Song Mingde was scheduled to depart on a six-month voyage to present-day Southeast Asia. During his travels, he would promote the Shu-style Chinese typewriter to overseas Chinese merchants in Luzon, Singapore, Java, Saigon, Sumatra, Siam, and Malacca.24

The national or civilizational significance of the Chinese typewriter was also a common selling point, both for promoters of the machine and for the inventors themselves. In the journal Tongji, Shu Zhendong reflected upon his pathway to Commercial Press and his development of the Chinese typewriter, lamenting as well that fewer and fewer Chinese compatriots “place importance on writing” (zhongshi wenzi).25 “A country’s writing is a country’s pulse,” Shu protested. “If the pulse dies out, what once was a country is no longer a country.”26 As for those who urged the abolishment of Chinese characters on account of the technological challenges of typewriting, he likened this to “refusing food for fear of choking.”27 For Shu Zhendong himself, as for his predecessor Zhou, the Commercial Press Chinese typewriter served as a tangible refutation of the idea that Chinese writing was incompatible with the demands of the modern technological age.

When the first Chinese typewriter rolled off of the Commercial Press factory floor, a fully formed Chinese typewriting industry did not miraculously spring into existence. The formation of a new industry would depend in equal measure upon the development of an entirely new clerical labor force: a battery of trained “Chinese typists” (daziyuan) to take up posts and put the machine to use in government, education, finance, and the private sector. In short, the development of Chinese typewriting required students of the Chinese typewriter—individuals whose bodies and minds would need to be trained to meet the requirements of this new machine, and to exploit its capacities.

Beginning in the 1910s and 1920s, a constellation of privately owned, one- and two-room typing institutes were established to meet this requirement, and to make money in the process. In Shanghai, Beijing, Tianjin, Chongqing, and other metropolitan areas, students received training in the new technology, typically over the course of terms lasting between one and three months, at the cost of fifteen yuan or less. Eager to secure employment as the first wave of human capital in this new clerical profession, these students would also play an important promotional role for Commercial Press itself—and eventually, as new entrepreneurs entered the market to compete with Commercial Press, for its competitors as well (a subject we will turn to later). By opening schools that specialized in a particular make or model of Chinese typewriter, and then securing employment for graduates, a manufacturer could begin to make inroads for his machine in the private, educational, and government sectors.28

When thinking about the history of typewriting from the context of the United States, where the profession was steadily and rapidly gendered as women’s work, one might be tempted to assume that Chinese typing steadily feminized as well. Perusing Chinese newspapers and magazines from the era, moreover, one would indeed have encountered a new figure in the Chinese periodical press that might reinforce this assumption: the “typewriter girl” (dazinü or nüdaziyuan). Typically in their teens and early twenties, these young women were featured alongside other “modern girls” of the era, encompassing painters, dancers, athletes, violinists, and scientists. They formed part of the still little-understood world of Republican-era professional women, entering not the blue-collar worlds of textile manufacturing, match factories, flour mills, and carpet weaving, but the white-collar worlds of administration and office work.29 Whether framed en plein air, as in a group photograph of Chinese typists in Beihai Park, or poised before their machines in traditional dress and finely parted hair, such representations in many ways accord with what one might expect at a moment in global history when clerical work was undergoing a process of feminization worldwide—the “typewriter girl” was, as has been argued, an “American export” (figure 4.4).30

4.4 Photograph of female Chinese typist, 1928; Eastern Times photo supplement (Tuhua shibao) [圖畫時報] 517 (December 2, 1928): cover

When we look beyond representations of Chinese typists in the periodical press, however, the archival records of these same Chinese typing institutes from the period reveal a strikingly different history. In data compiled on just over one thousand typing students enrolled in a variety of institutes between 1932 and 1948, more than 300 (or 30 percent) were, in fact, young men—far greater than found elsewhere in the world at this time.31 In other words, whereas mass media representations of Chinese typewriting suggested a profession that mimicked the prevailing gender norms of typewriting globally, the actual practice of Chinese typewriting did not. Typing in China remained a mixed labor pool throughout the period, with women constituting a larger, but by no means exclusive, share of the labor force. Young men, predominantly teenage and lower- or middle-school-educated like their female counterparts, entered these schools as well and sought training in the new technology. They graduated from typing institutes in sizable numbers. They served as typists. In certain cases, they went on to found typing schools of their own.32 One such example is Li Zuhui, a young man hailing from Wujin in Jiangsu province who himself was a graduate of the Chinese-American Typing Institute (Hua Mei dazi zhuanxiao). Li later went on to direct the Mr. Hui’s Chinese-English Typing Institute (Hui shi Hua-Ying wen dazi zhuanxiao)—a program founded circa 1930 in the Shanghai International Settlement with the stated aim of supplying “typing talent” (dazi rencai) to the Shanghai business community. In between, he served as a typist at the Zhili Province Bureau of Negotiations and the Tianjin Customs House.

To gain a better sense of the typing profession in its early formation, we must begin by looking at the schools where young people received training on this new device and from where they entered this new profession. At one end of the spectrum were small-scale training operations, such as the “Victory and Success Typing Academy” in Shanghai.33 Founded in May 1915 and originally focused on English typewriting, the two-room tutoring company eventually expanded into Chinese typewriting with the purchase of two machines. Circa 1933, the school enrolled six students in its English-language typing class and eight students in its Chinese typing class. At the other end of the spectrum, larger typing institutions were also in operation, such as the Shanghai-based Huanqiu Typing Academy with its hundreds of students. Founded in the fall of 1923, and originally focused exclusively on English-language typewriting as well, the institute expanded into Chinese typewriting during the fall of 1936, offering training on the Shu-style machine manufactured by Commercial Press.34 Founder Xia Liang, once an employee of the Standard Oil Company in Shanghai, developed his institute around a team of experienced professionals. The principal of the school, Chen Songling, was a graduate of the Shanghai-based Nanyang University, as well as a former employee of the Shanghai Customs House in legal translation. Working under Chen Songling were four tutors: Chen Jie, a graduate of Shengfangji Middle School in Shanghai, and a former employee of Standard Oil as well; Xia Guochang, a graduate of the Shanghai Business English Academy and a former employee of the Shanghai Telephone Company; Xia Guoxiang, formerly an employee of Robert Dollar and Company (Dalai yanghang); and Wang Rongfu, a graduate of the Shengfangji Middle School.

This overlapping network of pedagogical, entrepreneurial, and technological centers and practices combined to expand the network of the Chinese typewriter and Chinese typists into companies, schools, and government offices across the country. Schools placed their graduates in metropolitan and provincial governments throughout China, including the Nanjing Inspectorate, the Fujian Provincial Government, and the Sichuan Provincial Government; and major Chinese corporations such as the Chinese Soap Company, Macao China Bank, and the Zhejiang Xingye Bank.35 Graduates of the program also went on to teach Chinese typing in elementary schools. The Henan Provincial Government directed every department to dispatch secretaries to enroll in two-month courses in Chinese typewriting, for example, after which they would return to their original positions.36 Such training would make people better at their jobs, authorities argued, and would “contribute to emerging enterprise in China” (xinxing gongye).37

If the gender makeup of Chinese typewriting was a complex affair, and one that diverged sharply from its highly feminized counterparts in the United States and Europe, nothing within the contemporary Chinese periodical press would have suggested it. Whether in photographic spreads or news reports, male Chinese typists were conspicuously absent, with the new industry of Chinese typewriting presented as one dominated by young, often attractive female students and clerks.38 In 1931, the journal Shibao featured a photograph of the young female student Ye Shuyi as she practiced diligently at her Chinese machine.39 In a 1936 spread in Liangyou, a young female typist—in this case using an English-language typewriter—was featured alongside photographs of other “new women” (xin nüxing): women aviators, radio announcers, telephone operators, and beauty parlor owners.40 In a 1940 spread in Zhanwang, young women were shown at work on Chinese typewriters, accompanied by the caption “Type-writing is a congenial occupation for women.”41 Placing the Chinese typewriter girl in her broader context, the same spread included other “congenial” occupations such as nurse and flower seller. To emphasize the modern condition of Chinese women, though, the professions of lawyer and police officer were included in the mix as well. At all times, though, femininity and motherhood were honored, as stressed by another photograph and caption: “Mother teaching her child how to be a good girl.”

Male typing students sometimes did show up in photographic representations of Chinese typing, but in such cases their presence was subtly written out of the story by means of the contexts in which such photographs appeared, and the captions that accompanied such visuals. In 1930, for example, Shibao featured a portrait of eight young typing school graduates—six women and two men—with the caption “Graduates of Hwa-yin Type-writing School, Peiping.” While appearing gender-neutral at first, with the photograph including both men and women, and making no mention of the “typewriter girl,” nevertheless the surrounding photographs on the same page reveal the editor’s understanding of the typing profession as one with a distinctly feminized valence: “Modern Drill by Girl Students at Tsinghua University,” “Morning Drill by Girl Students at Nan-Kai University,” as well as photographs of three young female athletes.42 Still other images were starker in their erasure of male typing students, as in a photographic spread from Great Asia Pictorial, also in 1930. In this photograph, twenty-two Chinese typing students were shown—fifteen women and seven men—and yet the caption read: “Photograph of First Entering Class of Female Students at the Liaoning Chinese Typing Institute.”43

An important tension emerged, then, between the lived experience of Chinese typewriting and the images that these schools and Chinese media outlets chose to represent it. What accounts for this discrepancy? Here we must once again return to the global context within which Chinese typewriting was taking shape and was at all times nested. At the very moment China began to form its own typing industry, there already existed such a thing as a “typewriter girl,” a robust trope that had found expression globally in a wide variety of cultural and socioeconomic contexts. By contrast, nowhere on earth did there exist the trope of the “typewriter boy,” in the sense of a comparably powerful discursive or representational formulation that captured this reality in the form of stereotype. In the United States, the displacement of male typists and stenographers was part of the history of industrial mechanization, a history in which routinized forms of work were increasingly delegated to young women starting at the end of the nineteenth century.44 Similarly, typewriter manufacturers worldwide had by this point long encouraged this trend toward feminization, targeting women both as potential consumers and as vehicles for the popularization of their new machines. The Remington Company went so far as to encourage consumers to purchase machines and donate them to women as a kind of charity. “No invention,” the company’s advertisement boldly proclaimed in 1875, “has opened for women so broad and easy an avenue to profitable and suitable employment.”45 Companies also employed young female typists during sales calls. In 1875, for example, Mark Twain purchased his first typewriter from a salesman who employed a “type girl” to demonstrate the apparatus.46

By contrast, the male Chinese typist was discursively invisible, with typewriter companies in China perpetuating the idea that the sine qua non of a modern office was a young female typist—echoing the Western world even though Chinese realities were more complex.47 To be sure, parties in China could in theory have invented a stereotype of a male typist, were they sufficiently committed to fabricating new tropes that better captured the on-the-ground realities of the Chinese typing school and typing pool, and yet the periodical and archival records suggest strongly that no such discursive enterprise took place.

When young Chinese women and men entered a typing school and encountered a Chinese typewriter for the first time, one question would have quickly surfaced: How were they to memorize the locations of the more than 2,000 characters arrayed in front of them on the tray bed? What kinds of memory practices were young students to employ, and what kinds of typing pedagogies were available to familiarize them with this new technology? While the relationship between technolinguistic forms and embodied practices has received considerable attention in the West, remarkably less is known about the modern Chinese context. As Roger Chartier has demonstrated, the advent of new linguistic technologies and material forms in Europe enabled and constrained the body in unprecedented ways. The codex, as a form, permitted modes of pagination impossible with the scroll, which in turn rendered possible the creation of indexes, concordances, and other referential paratechnologies. Within this new technosomatic ensemble, the reader was now able “to traverse an entire book by paging through.”48 Unlike the scroll and its accompanying requirement of two-handed reading, moreover, the codex “no longer required participation of so much of the body,” liberating one of the reader’s hands to, among other things, take notes.

Far less is known about the somatic dimensions of modern Chinese linguistic technology—and, in the case of Chinese telegraphy, typewriting, stenography, braille, and typesetting, hardly anything at all.49 In the case of the Chinese typewriter, a new type of body came into being: a novel coalescence of physical postures, dexterities, forms of coordination and visualization, and types of corporeal and psychological stress, all of which diverged from more familiar contexts of clerical work in the West and offer us a vibrant counterpart with which to think more expansively about forms of physical and mental discipline. Republican-era typing schools offer us a window into this history, particularly in those schools where students had the opportunity to study both Chinese and English typing. When comparing the two curricula, we find that Chinese typewriting encompassed its own distinct physical regimen, in terms of the demands it placed on memory, vision, hands, and wrists.50

Students of Latin-alphabet typing in the Chinese schools were required to take courses in “practicing fingerwork” (lianxi fenzhi) and “blind typing” (bimu moxi) still familiar to Western students even today. By comparison, students of Chinese typewriting took an utterly different battery of classes which included “character retrieval methods” (jiancha zi fa) and “adding missing characters” (jiatian quezi), among others. While certain properties of alphabetic scripts—in particular, the limited number of modules—factored heavily in the development of “blind” typing as an ideal, there was no such commitment to blind performance in Chinese typewriting. If the QWERTY operator was trained to type without looking at the keyboard, the Chinese typist was encouraged to rely heavily on his or her faculties of vision, both direct and peripheral, and to push them to ever higher and subtler states of refinement.

Chinese typewriters and English typewriters differed as well in terms of the somatic regimens that their operators followed in order to achieve proficiency. From a very early stage, the alphabetic typewriter had been brought into conceptual and practical relationship with the piano and piano playing, not only in terms of the keys that bedecked both instruments, but also in the formulation of training modules that resembled musical études (hence the frequent proposition in the West that women with backgrounds in piano playing made ideal candidates for clerical careers). Ideas and practices of posture were likewise borrowed frequently from the realm of piano playing, as were notions of the relative strength and dexterity of individual fingers. Both pianist and typist were meant to maintain a posture of composure and lithe fixity in their torsos and necks, with wrists neither slumping downward nor protruding upward; and both were supposed to concentrate their attention upon the orchestrated movements of the outermost extremities of their fingers. Central to Western typewriting was a hierarchy of strength, dexterity, and utility between the index, middle, ring, and pinky fingers.

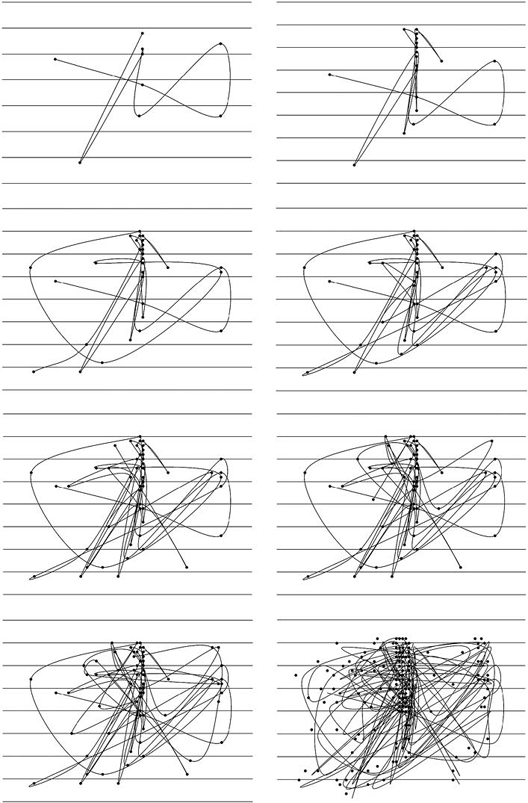

The training of Chinese typewriting was, by contrast, oriented toward helping the student bring the tray bed of his or her machine “into play”—to warm up the cold gray surface of the character matrix by walking around in it and learning its cartography—not entirely unlike the training of Chinese typesetters. To this end, typing lessons were centered around a distinct set of repetitive drills, beginning with common Chinese terms and names. These drills helped familiarize one with the absolute locations of individual characters on the tray bed, but more subtly they imprinted in memory the spatial relations between those characters that tended to go together. In the very first lesson of a typing manual from the 1930s, for example, students drilled by repeatedly typing the common two-character words “student” (xuesheng), “because” (yinwei), and two dozen others. By practicing with such words, the lexical geometries of Chinese became imprinted within the muscle memories of the student. One might not recall precisely where xue and sheng or yin and wei were in the absolute sense of x-y coordinates, but over time one would recall the general sensation of these altogether common two-character compounds.51

Rather than simply seeking out a character on the tray bed, moving toward it, performing the type act, and then repeating this same process for the subsequent character, the trained Chinese typist was urged to refine a sensitivity to, one might say, the instantly immediate future—that is, the very next character. Upon setting out toward the first desired character, the typist was to have already begun the process of transferring a portion of her concentration to the next, performing each type act such that, at any given moment or state, she embodied a psycho-corporeal anticipation of the next.52 Typists were also trained to become sensitized to the materiality of signifiers.53 Each time the typist depressed the selection lever, the force of each type act had to be finely attuned to the weight of each character, a measurement that corresponded directly to the character’s stroke count. Should one type the single-stroke (and thus lighter) character yi (一 “one”) with the same force as the sixteen-stroke (and thus heavier) character long (龍 “dragon”), one would quite likely puncture the typing or carbon paper and have to begin the document anew. To type long with the same force as yi, however, would result in a faint, illegible registration (also making it ill-suited for carbon-paper copying). Trained operators necessarily varied the force with which they typed different characters so as to maintain a chromatic consistency across the text, and to avoid puncturing the paper.54 With this technology, then, the longstanding Chinese concept of “stroke count” was translated into the physical and corporeal logics of mass, weight, and inertia.55

4.5 Chinese typewriter training regimen (sample), showing typist’s movement from character to character within typewriter tray bed

In light of the strides made by Commercial Press in the launch of their new typewriter division, anyone paying attention to developments in China would have witnessed the unmistakable signs of a vibrant new industry, complete with an emerging network of training institutes. By the 1920s and 1930s, indeed, there existed across China a disciplinary practice in which typists used the machine, and further brought their own bodies into accordance with it. It would not have been surprising, then, to have encountered the 1920s report in the Remington Export Review that proclaimed, “After a great many years of futile experimentation, a typewriter for the Chinese language has at last been perfected.” The Western world, it would seem, was finally taking notice.

Remington Export Review was not referring to Commercial Press, however, nor to Shu Zhendong’s machine. The company newsletter was referring to Remington itself. “Robert McK. Jones, head of the typographical department of the Remington Typewriter Company and a Remington man for thirty-seven years,” it continued, “is responsible for its production.”56 A photograph of a white-bearded Jones accompanied the piece, beneath it the caption “Who Developed the Remington Chinese Typewriter.” The title of the piece said it all: “At Last—A Chinese Typewriter—A Remington.”

Robert McKean Jones was Remington’s principal developer of foreign-language keyboards and director of the development department.57 Born in 1855 in the Wirral in northwest England, near the border of Wales, he operated a workshop in New York where he designed an estimated 2,800 keyboards for a diverse collection of scripts. Jones was one of the foremost technicians behind the globalization of the Remington typewriter examined in chapter 1. He personally adapted the single-shift keyboard machine to a reported eighty-four different languages, a feat that earned him the honorific of “master typographer.” With his command of sixteen alphabets, a trade journal reported in 1929, “there is hardly a language spoken of which he has not at least a working knowledge.”58

Having completed an Urdu keyboard in 1918, and then keyboards for both Turkish and Arabic in 1920, Jones was an obvious choice to lead the company’s new Chinese initiative.59 In the winter of 1921, Remington set out to create a “Chu Yin Tzu-mu Keyboard,” also known as the “Phonetic Chinese” keyboard, assigning this project to Jones.60 The Chinese typewriter of Jones’s invention was unlike anything we have encountered thus far, however, for one remarkable reason: it contained almost no Chinese characters. With the exception of Chinese numerals, the remainder of his keyboard was dedicated exclusively to symbols from the recently developed Chinese Phonetic Alphabet. Jones offered brief details regarding the language reform efforts then afoot in China upon which his invention was premised. “The Chinese Government has officially adopted and is promulgating a new phonetic alphabet known as the ‘Chu Yin Tzu-mu,’ or in English, national phonetic alphabet. A formal edict commanding its use by Government officials and requiring the teaching of the system in schools has been published.”61 Jones explained that the new alphabet was “devised by a council of learned men from all sections of the country” and that its objective was to “simplify the ancient complicated system of ideographic characters and promote literacy among the people generally.”62 Jones and his patrons at the Remington typewriter company submitted their own application for a National Phonetic Chinese typewriter on March 12, 1924, even before the government of the Republic of China issued its formal promulgation of zhuyin fuhao (figure 4.6).

4.6 Robert McKean Jones/Remington Chinese typewriter (1924/1927)

The cognitive dissonance of this machine—a “Chinese typewriter” with no Chinese characters—was not lost on those journalists who first wrote about the invention. “A Chinese typewriter?” began Paul T. Gilbert in his piece for Nation’s Business. “Well, I suppose you might call it that; but don’t look for any of Wang Hsi-cheh’s 5000 symbols on the keyboard,” referring to Jin dynasty calligrapher Wang Xizhi (303–361). Gilbert concluded by assuring his readers, however: “It would have been impossible to devise a keyboard which would lend itself to the typing of the Chinese language.”63

Robert McKean Jones was not the first typewriter inventor to seize upon the dream of a “Chinese alphabet” or “phonetic Chinese” as an entry point into the vast and still untapped Chinese-language market—and neither was Remington. One decade earlier, in the winter of 1913, two UK-based engineers had submitted their own joint patent application geared toward “adapting the Chinese language to the production of printed or typewritten matter.”64 John Cameron Grant and Lucien Alphonse Legros explained in the course of their patent application that their machine would not feature Chinese characters per se, but rather a phonetic Chinese “alphabet” that was currently in circulation in China. “Within the last few years,” Grant and Legros explained, “a new Chinese alphabet, or more strictly speaking, syllabary, has come into certain vogue and semi-official use.” This development would come as a relief both to China and to the wider world, the inventors explained, insofar as a character-based typewriter was itself an impossibility. Regarding China’s character-based script, “its adaption for modern machine composition is entirely out of the question, as it would be quite beyond the range of practical possibility to cut and apply such a number of matrices to any known form of machine composition, or indeed, to bring the whole language easily into the compass of any known power of manual composition at case.” Meanwhile, however, any attempt by foreigners to develop “Romanized” versions of Chinese was equally bound to fail. Foreign Romanization schemes “have grave disadvantages, firstly, from the fact that the alphabet itself is foreign, and therefore objectionable,” and secondly that they require the usage of additional symbols to convey Chinese tones.65

But the script that would form the basis of their typewriter was something apart—it had been invented in China and by Chinese. In the wake of the 1911 revolution that overthrew the Qing dynasty (1644–1911), the newly established Ministry of Education of the Republic of China under Cai Yuanpei announced plans to convene a Conference on Unification of Pronunciation. Under the direction of Wu Zhihui, the meetings commenced in February 1913 and were attended by many of the country’s most prominent language reformers. Over the span of approximately three months, and a contentious and complex set of discussions, the committee announced an agreement that centered around a phonetic notation system for Chinese known as zhuyin zimu—or “phonetic alphabet.”66 Here, then, was the opportunity that Western typewriter companies had been waiting for: a Sino-foreign script, invented “by and for” the Chinese, but employing a Western system of script.

Legros and Grant were not alone in imbuing this new “Chinese alphabet” with a sense of possibility and promise. In the very same month they submitted their patent application, so too did J. Frank Allard, an engineer working in collaboration with the Underwood Typewriter Company to retrofit a standard Underwood machine with the new phonetic symbols.67 In April 1920, the Telegraph-Herald announced that the “Chinese Alphabet has been reduced.”68 “Chinese of future generations,” the article began, “will write in phonetic script and use a typewriter with only 39 characters instead of plying a brush to draw 10,000 or more hieroglyphics if mission workers succeed in an effort they are making to revolutionize handwriting in use in China for more than 4000 years.” The system had been developed in 1903 in England by Wang Chao, the article explained, and had already been the subject of interest for designers of a Chinese typewriter. Reverend E.G. Tewksbury of Shanghai, it was reported, “has put the new script into use on American typewriters with complete success,” with the font being provided by Chinese engravers. In August 1920, Popular Science featured an advertisement for yet another phonetic Chinese typewriter: the Hammond Multiplex.69 By the time Robert McKean Jones signed his name to the Remington Phonetic Chinese typewriter, then, his was already one in a long genealogy.

Even as the dream of a “Chinese alphabet” seemed to be coming true, a stark reality confounded the aspirations of these Western typewriter manufacturers: zhuyin was never meant to replace Chinese characters. It was never meant to become a “Chinese alphabet” in the sense understood by Remington, Hammond, Underwood, and others. Rather, zhuyin was meant to serve as a pedagogical, paratextual system through which to inculcate in the Chinese people the standard, nondialectal pronunciations of Chinese characters. This fact was lost, however, on many foreign observers, most notably foreign inventors eager to develop phonetic Chinese typewriters and hot-metal composing machines. Much like Vladimir and Estragon waiting endlessly for Godot, observers of China persisted in a kind of imperturbable anticipation, poised to wait endlessly for a Cadmus—a figure preordained to come to China at some point (always in the near future) and bring with him the wonder and salvation that is the alphabet. As the mythological founder of Thebes and brother of Europa, Cadmus was credited by Herodotus as being responsible for introducing Phoenician script to the Greeks—the forerunner to the Greek alphabet, that invention to which Walter Ong, Eric Havelock, and many others have attributed causal power as a contributor to the Greek Miracle, as discussed earlier. If only Cadmus would hasten to arrive here in the Celestial Kingdom, all of the many woes that had beset the world’s last great non-cenemic script would be resolved.

Returning to Remington and Jones, we see how the many “false Cadmus sightings” in the twentieth century may have dented, but in no way destroyed, confidence in his eventual arrival. (“I can’t go on like this,” Estragon protests. “That’s what you think,” Vladimir responds.) Not five months after Remington submitted its application to the Patent Office, a full-page advertisement appeared on the back cover of China’s premier language reform journal, the National Language Monthly (Guoyu yuekan), which regularly featured the writings of Zhao Yuanren, Li Jinxi, Qian Xuantong, Zhou Zuoren, Fu Sinian, and other influential figures in the country’s language reform movement. The advertisement featured the Underwood Chinese National Phonetic Typewriter (Entehua Zhonghua guoyin daziji), offering a photographic preview of the keyboard, and the assurance that “its construction is the same as the English language Underwood Typewriter” (qi gouzao shi yu entehua yingyu daziji xiangtong). Along the bottom edge, readers saw the output of the machine, in a single line of zhuyin script: ㄣㄊㄜㄏㄨㄚ ㄍㄨㄛ|ㄣ ㄉㄚㄗㄐ| (entehua guoyin daziji) or “Underwood National Phonetic Typewriter.”70

Despite such giddy optimism within the industry, all attempts to market and mass-produce phonetic Chinese typewriters failed. Western companies never understood—or perhaps even bothered to understand—the limited orientation of these phoneticization movements among the “Celestials.” Instead, in their never-ending wait for the annunciation of the “Chinese alphabet,” Remington, Underwood, and others stood poised and alert, ears perked to hear the footfalls of an approaching Cadmus before their competitors did, so as to be the first to meet him at the gates and capitalize on his arrival.

So entrenched was this idea of a phonetic Chinese typewriter that, indeed, even the utter failure of these phonetic Chinese machines escaped the attention of Western media. When Jones died in 1933 in Stony Point, New York, his obituary made no reference to his Arabic machine, nor to the keyboards he designed for Urdu or other scripts. Instead, the notice of his death spotlighted perhaps the only keyboard in the inventor’s career that ended in utter failure: “Robert McKean Jones: Inventor of Chinese Typewriter Was Able Linguist.” “The development of the Chinese typewriter twenty years ago by Mr. Jones,” it continued, “was considered an outstanding achievement. The many characters in the language were believed to constitute an insuperable handicap. Mr. Jones, an accomplished linguist, worked for years in consolidating the various Chinese characters on the keyboard of a machine in a manner that is legible and intelligible to citizens of that country where there are many dialects and many alphabets.”71

Whatever strides the Chinese typewriter might have been making at home, the domestic industry alone was clearly not enough to cement China’s place within the global family of modern technolinguistic countries. As long as the “real” typewriter existed out in the wider world, and as long as the world outside China remained unprepared to conceptualize the Chinese typewriter as anything but an absurdity, the status of this machine would remain in question—particularly its eligibility to bear the moniker of “typewriter.” In 1919, the journal Asia featured a photograph of Fong Sec, then editor in chief of Shanghai Press, standing before a Commercial Press machine. “Dr. Fong Sec,” the caption read, “stands for the best type of the efficient, modern Chinese,” in what would begin as a glowing report. “As an editor of the Shanghai Press, the largest and best equipped of Chinese printing firms, responsible for the publication of almost all Chinese text-books and the dissemination of literature throughout Central China, he holds a position more significant from the point of view of the enlightenment of the people than that of any official of state.” What praise was afforded Fong Sec himself was promptly withdrawn, however, once focus shifted to the contrivance before which he stood. “In this picture he is shown with the elephant of typewriters,” the article continued, “conceived by a son of the fathers of invention.”72

During the 1920s, Commercial Press set out on its first concerted effort to win over the Western world and change its views of the Chinese typewriter. The machine’s global debut took place in Philadelphia at the Sesquicentennial International Exposition of 1926, mounted in celebration of the 150th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. On display would be the cultural and industrial heritage of the global community, with pavilions dedicated to Japan, Persia, India, and more. The Chinese pavilion was overseen in part by Zhang Xiangling, the Chinese consul general in New York, a man for whom the presentation of his country on the global stage was of the utmost concern.73 Three years prior to the exhibit, circa 1923, Zhang had paid a visit to the Philadelphia Commercial Museum and its display dedicated to Chinese products. “They were disappointed,” a report from the period read, referring to Zhang and a group of Chinese businessmen who had accompanied him, “to find that the exhibit, large and handsome as it is, represented the China of the past rather than the new China with its diversified production.” “For instance, there were relatively few specimens illustrating the modern industries of the country and the manufactures which China has developed within recent years.” To remedy this situation, Consul General Zhang promised to the museum curators that he would reach out to parties back home and secure a “representative series of samples of Chinese products” for the museum. A few months later, Zhang’s promise was fulfilled, with seven cases of materials arriving in Philadelphia, sent by the Shanghai Chamber of Commerce. Included in the collection were samples of silk fabrics, wicker furniture, tobacco and cigarettes, tooth powder, and hosiery, among many other items.74

The Chinese typewriter by Commercial Press was selected as one such exemplary object—a device to display the progress of the nation in the industrial arts, while at the same time situating this machine in a longer framework of Chinese civilizational history. Upon entering the pavilion, one immediately encountered the American and ROC flags, draped side by side, as well as fine silks, ornate umbrellas, tea pots, porcelain vases, five-colored glass, calligraphic scrolls, and landscape paintings. Along the rear wall, just right of center under an image of George Washington and a painting of a wildcat poised upon a tree limb, was a display case with an engraved plaque: “Chinese Typewriter” (figure 4.7).75

4.7 Shu Zhendong Chinese typewriter (lower left) at the Philadelphia world’s fair

In preparation for the machine’s global debut, Commercial Press crafted an English-language brochure for the Shu-style machine. The tone was carefully phrased for a foreign audience, taking the machine out of its indigenous framework of manuscript and printing, and in a rare instance suggested that it was in fact on par with the real typewriter of the Western world. “The Chinese typewriter manufactured by the Commercial Press solves a serious problem in office administration in China,” the brochure read. “The machine has all the advantages of a foreign typewriter” (figure 4.8).76 As commissioner general representing China at the Philadelphia world’s fair, Zhang must have been pleased by the typewriter’s performance and reception.77 Commercial Press received a “Medal of Honor” for “Ingenuity and Adaptability of the Chinese Typewriter.”78 “It is a miraculous achievement of the inventor that, although there are 3,000 characters in the font,” a Philadelphia guidebook read in a rare celebration of a Chinese machine, “yet a typist, after the practice of one or two weeks, will be able to locate any character instantly. 2,000 characters can be written after two months’ training, and greater speed can be obtained by longer practice.”79 News from Philadelphia began to reach China starting in the winter of 1927, moreover. On January 12, Shenbao relayed communications from Zhang, containing information on those Chinese companies that received honors and awards. Among those awarded was Commercial Press, specifically for the Shu-style Chinese machine.80

4.8 Commercial Press brochure for the world’s fair

A medal of honor in Philadelphia was insufficient to quiet criticism and denigration, however, not only from foreigners but also closer to home. In 1926, the same year as the world’s fair, linguist and vociferous character abolitionist Qian Xuantong once again railed against the inefficiency of character-based systems of categorization, reproduction, and transmission, leveling a critique against a wide range of objects. Beginning with a critique of character-based dictionaries, catalogs, and indexes, Qian argued that “Chinese characters offer no effective solution, whether it be stroke-count, rhyme schemes, or by relying on the most dog-fart of them all, that radical system from the Kangxi Dictionary.”81 Qian reserved his most strident criticism for the Chinese typewriter:

And then there are typewriters on which one cannot have less than two to three thousand characters. The surface area of two to three thousand characters is not small, mind you. When typing, no matter how familiar one is with these two to three thousand characters, one has little choice but to search for each character one by one. The first character is all the way in the northeastern corner. The second character is over in the southwest corner, eighth from the bottom. The third character is, once again, up in the northeast, in the third column just off center, eleventh from the top. The fourth character is up in the northwest corner, down a bit. The fifth character is once again in the middle, just a bit southeast of central. And so on. It’s really enough to leave one bewildered (mumi wuse). And when you come to a character that’s not on the machine, and when you can’t find it in the “rarely used character tray bed” (since the rarely used character tray bed doesn’t have all the characters either), and when you have to write in the character by hand, then you’ll see for yourself how much of a hassle it is. Phonetic script has only a few dozen characters and a handful of symbols, so it goes without saying how convenient it is for typing.82

Qian’s cartographic imagery was playful and devastating. Setting the stage for his critique with the deft use of the term “surface area” (mianji)—a term typically reserved for territorial expanses—he transformed the Chinese typist into a lost soul wandering across an expansive landscape of the twice-repeated “two to three thousand characters.” To elongate this sense of distance, Qian expressed the location of characters on the tray bed using cardinal directions, the way one might express the location of provinces or cities in China itself. Qian’s first hypothetical character was located somewhere in the province of Fengtian, his second in Yunnan or southern Sichuan, his third perhaps in Rehe, his fourth in eastern Xinjiang, and his fifth in Shaanxi.

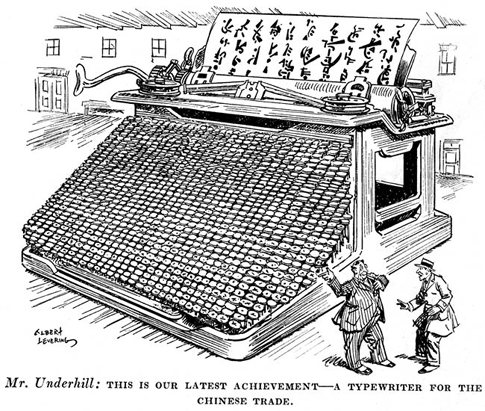

Meanwhile, back in the United States, the Chinese pavilion in Philadelphia seems to have inspired yet another instantiation of the Chinese monster we first examined in chapter 1. In the February 17, 1927, issue of Life magazine, cartoonist Gilbert Levering presented his vision of a “Chinese Language Typewriter”: a colossal contraption featuring a keyboard roughly thirty keys wide by thirty-five keys deep—for a rough total of 1,050 keys in all (figure 4.9).83

4.9 “Chinese Language Typewriter” in Life magazine, 1927

Twenty-seven years since making his first appearance in the popular press, it would seem, “Tap-Key” was alive and well.