7.1 Propaganda poster featuring Chinese typist

One person setting three or four thousand characters [an hour] doesn’t amount to much. But if everyone were to set three or four thousand characters, now that’d be something.

—Zhang Jiying, Chinese typesetter, 1952

Long before I set out to write a history of the Chinese typewriter, I spent years staring at it without so much as realizing. In the research for my first book, a history of China’s Ethnic Classification project (minzu shibie), I had pored over ethnological and linguistic reports authored by social scientists working in the southwestern province of Yunnan. In composing their studies on the categorization of ethnic identity in the region—reports I reread an untold number of times—researchers had often relied upon the very Chinese typewriters that would later constitute the focus of my research. The Chinese typewriter had been hiding in plain sight all those years.1

Alerting colleagues and friends in the field, I organized an informal “search party” for other purloined letters. I offered a brief crash course in how to identify typewritten documents (especially how to distinguish them from printed texts), and requested their assistance in surveying their own personal collections and archival holdings. Telltale signs included: occasionally handwritten characters tucked in amid typewritten ones (i.e., infrequent characters for which no character slug was available on the machine), the alternating faintness and darkness of different passages (an issue we discussed in chapter 4), an ever-so-slight zigzag of the text baseline, and the somewhat wider-than-normal spacing between characters. The hunt was on.

A new golden age in the history of Chinese typewriting rapidly came into view, with colleagues sighting the machine all the way from the metropolitan areas of Beijing, Shanghai, Harbin, and Kunming to remote regions of western China. No later than May 1950, the Political Protection Office of the Harbin Municipal Bureau of Public Security began to type up its surveillance reports, as shown in local investigations of Catholic communities.2 In Beijing, typewritten reports from the Beijing Municipal Vice Food Products Industry Party appear no later than 1952.3 Provincial-level Party secretaries in Hebei began producing typewritten documents no later than 1955.4 Typewriting was no means limited to larger urban centers, moreover. In the county of Baoji in Shaanxi province, typewritten documents appear by 1957 in survey reports on local conditions.5 Most telling of all, typewritten reports from 1956 and 1957 were produced in the remote pastoral region of Zeku county, Qinghai province.6 Images of patriotic Chinese typists soon appeared as well, celebrated for producing the paperwork of state-building, postrevolutionary consolidation, economic planning, and class struggle. In March 1956, the Chinese typewriter made new strides with its first appearance within a Mao-era propaganda poster (figure 7.1).7

7.1 Propaganda poster featuring Chinese typist

The 1950s marked a more vibrant period of Chinese typewriting than I had imagined, surpassing the late Republican period in extent and usage. During the Maoist period, an unrelenting series of sociopolitical and economic campaigns placed an unprecedented burden on Chinese typists, who found themselves tasked with the production of economic reports and low-run mimeographed materials for use in the ubiquitous “study sessions” taking place in work units across the country. So heavy was the burden on typists, indeed, that some work units resorted to outsourcing jobs to nonofficial “type-and-copy shops” (dazi tengxieshe), a phenomenon that raised concerns within the fledgling Communist state. With the proliferation of small-scale, independently operated typing shops, the Party-state’s monopoly over the means of technolinguistic production was to a degree compromised, insofar as the same collection of typewriters, carbon paper, and mimeograph machines used to print and distribute state-commissioned speech transcripts, political study guides, and statistics was also being used to run a small-scale gray market publishing industry.

Chinese typewriters were used elsewhere to reproduce entire books, known as dayinben (“typed and mimeographed editions”), a mode of publication so prevalent that the term was later repurposed in the computer age as the Chinese translation of “to print out” (dayin) and “laser printer” (jiguang dayinji). In one type-and-mimeograph edition from 1968, a self-identified Red Guard typed and mimeographed the poetry of Chairman Mao, releasing the edition in time for International Workers’ Day. In an even more profound act of devotion, members of the “Yunnan University Mao Zedong-ism Artillery Regiment Foreign Language Division Propaganda Group” transcribed Mao’s speeches delivered during the years 1957 and 1958, copied from the People’s Daily, the China Youth Daily, the New China Bimonthly, the Henan Daily, and others. Extending to over 280,000 characters in length, with page after page of densely packed typewritten text, this work would have taken between 100 and 200 hours—or four to eight full days—to type and mimeograph (figure 7.2).8

7.2 Type-and-mimeograph edition of Long Live Chairman Mao Thought. Selections from 1957 and 1958 (c. 1958)

Occupying the vast terrain between handwriting and the printing press, type-and-mimeograph editions continued into the Reform Era (1978–1989). The nationally circulated Reform Era literary journal Today!, described by Liansu Meng as the “first unofficial journal in China since 1949,” was composed using a Chinese typewriter and mimeograph stencils.9

The most fascinating dimension of Chinese typewriting in the second half of the twentieth century was not its prevalence or scope, however. Within this bustling world of typist activity, something else genuinely revolutionary was unfolding. Everyday clerks and secretaries in the Mao era spearheaded a series of innovations, centered around experiments with alternate ways of organizing the Chinese characters on their tray beds. Instead of adhering to radical-stroke organization—or indeed any of the experimental character retrieval systems designed by Chinese elites, as examined in the preceding chapter—these typists undertook a “radical departure,” in both a figurative and literal sense. Specifically, they created their own idiosyncratic natural-language arrangements of Chinese characters designed to maximize the adjacency of characters that tended to appear together in actually written language, whether in the form of commonly used two-character compounds (known in Chinese as ci) or in key names and phrases within Communist nomenclature, such as “revolution” (geming), “socialism” (shehui zhuyi), “politics” (zhengzhi), and others.10 Owing to the increased proximity of co-occurring characters, and the repetitiveness of Communist rhetoric, typists who used this experimental method boasted speeds of up to seventy characters per minute, or at least three times faster than the average typing speed in the Republican period.

In other words, among Mao-era typists we can trace the earliest known experimentation with and implementation of an information technology currently referred to as “predictive text”—now a common feature in Chinese search and input methods. Indeed, if “input methods” (shurufa) have been one of the pillars of modern Chinese information technology, as we examined in the preceding chapter, the second pillar is undoubtedly that of predictive text. It may come as a surprise that a technology so familiar to denizens of the digital age has deeply analog roots: Chinese predictive text was invented, popularized, and refined in the context of mechanical Chinese typewriting before the advent of computing. What is more, this innovation cannot be ascribed to a single inventor, but rather came into being through a diffuse collective made up of largely anonymous typists.

In November 1956 a typist in the central Chinese city of Luoyang accomplished an astonishing feat. Using a mechanical Chinese typewriter, the very same we have come to know well over the course of this book, the operator typed 4,730 characters in one hour, setting a new record just shy of eighty characters per minute.11 While seemingly unremarkable when considered within the more familiar context of alphabetic typewriting, the magnitude of the record becomes apparent when one considers the average speed of Chinese typists at the time: twenty to thirty characters per minute. This accomplishment thus represented a two- to fourfold acceleration of the apparatus. The typist had not achieved this record by means of electrical automation, moreover, or a new kind of typewriter. Instead, he had simply rearranged the Chinese characters on the machine’s tray bed. Moving away from the longstanding taxonomic system of radical-stroke organization, and eschewing even the most experimental of character retrieval systems developed in the Republican period, the typist in 1956 reorganized the characters on the machine into natural-language clusters designed to maximize the adjacency and proximity of those characters in the Chinese language that tended to go together in actual writing.

Newspapers in the opening decades of the People’s Republic of China (1949–present) were replete with stories of “model workers,” proletarian champions who displayed feats of unprecedented production through the combined application of will and wisdom. While such exuberant claims cannot be accepted uncritically, in the case of the “model typist” from Luoyang, a diverse body of archival sources and material artifacts has led me to trust the accuracy—and perhaps even the quantitative claims—of this remarkable report.

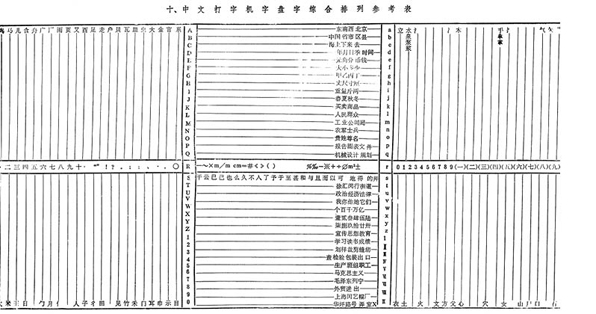

To illustrate this typist’s system briefly—we will return to it in greater detail later—we can examine a sample arrangement included as part of a 1953 introduction for the public. The principles of this experimental organization can be seen in figure 7.3.

7.3 Sample of new character arrangement; from “Introduction to the ‘New Typing Method’ (‘Xin dazi caozuofa’ jieshao) [‘新打字操作法’介紹],” People’s Daily (Renmin ribao) (November 30, 1953), 3 (Romanizations included for purposes of illustration only)

Beginning with the character gao (告), shaded in gray, we find located within the adjacent cells the characters bao (報) and zhuan (轉)—each of which can be combined with gao to form common two-character words: baogao (報告), meaning “report,” and zhuangao (轉告), meaning “to pass on” or “transmit.” Continuing our exploration from the vantage point of these two characters, we see further layers within this associative system. Adjacent to the character bao, we find three additional characters with which bao can be meaningfully combined: cheng (呈), hui (匯), and zhuan (轉), which can be paired to produce, respectively, chengbao (呈報 “to submit a report”), huibao (匯報 “to give an account of”), and zhuanbao (轉報 “message transfer”). Still other combinations surround the character shang (上), combinable with those of xia (下), bian (邊), and shu (述) to form “above and below,” “top,” and “above-mentioned,” respectively. All told, the area pictured here contains no fewer than twenty-five perfectly adjacent compounds, as well as an additional set of proximate compounds. This density is impressive when we consider that there are only thirty individual characters in this sample area, out of the total number of 2,450 on the tray bed (all of which, as we will soon see, were likely organized in the same associative fashion), and that these characters would not have been adjacent if organized according to the conventional radical-stroke system. Using machines with this new method of character organization, typists in the early Maoist period set out on one of the most sweeping technolinguistic experiments in the modern age.

This transformation should be understood less as a leap of imagination and cognition than as the manifestation within a particular political environment of a longstanding, deeply corporeal relationship that obtained between machines and human bodies—or what Ingrid Richardson refers to as the “technosomatic” complex.12 The sudden rearrangement of characters on Communist-era tray beds can be understood only if we see it as part of the much longer historical process we have examined thus far: an aggregation of tactile, decentralized, and largely unnoted experiences of thousands of typists and typesetters, individuals who interacted with their character racks and tray beds in embodied, nonverbal ways. It was within this hum of activity, and over the course of countless millions of fleeting, nanohistorical moments, that the leap to natural-language arrangement became conceivable, practicable, and, within the political milieu of the Maoist period, celebrated and incentivized—the countless acts of picking up type, setting it back down, moving from one character to the next on the typewriter, depressing the type lever, and so forth. To understand the history in question, it is essential that we engage with the habitus of Chinese technolinguistic practice, the “embodied history, internalized as a second nature and so forgotten as history.”13

The origins of this diffuse, decentralized, and grassroots movement are impossible to identify with certainty, and yet available evidence helps us trace out its contours with some confidence. The earliest and clearest example is found in the activities, not of a typist, but of a typesetter named Zhang Jiying, who became known to readers of the People’s Daily in 1951 in an article entitled “Kaifeng Typesetter Zhang Jiying Diligently Improves Typesetting Method, Establishes New Record of 3,000-plus Characters per Hour.”14 Having worked as a typesetter for over a decade, first in the city of Zhengzhou and later in Kaifeng, Zhang was trained on both the older “24-tray character rack” and the newer “18-tray character rack,” and posted very respectable typesetting speeds (ranging from 1,200 to 2,200 characters per hour over the course of his career thus far).15 Only a few short months after the formation of the PRC, however, he experienced a reported surge of inspiration and began to engage in a sweeping, experimental reorganization of his character rack—an experiment that culminated in his 1951 feat.

What caught Zhang’s attention in particular was his colleagues’ practice of pairing characters together on the character rack that they employed frequently in the course of daily work. Three characters in particular had been clustered together, in clear violation of radical-stroke organization: xin (新), hua (華), and she (社), which together form the name “New China Press” or Xinhuashe. “I thought, if one were to put a group of related characters together,” Zhang would later explain, “it would definitely be good for setting.”16

Zhang set out to apply this principle across his entire character rack. His character rack would soon feature over 280 two-character compounds, eight three-character sequences, and even seven four-character sequences, a style of organization he termed lianchuan—meaning “series” or “chain.”17 He included terms and names such as “revolution” (geming), “American imperialist” (Meidi), “liberation army” (jiefangjun), “agriculture” (nongye), and many others employed in Communist parlance. These were cliché, in the original French meaning of the term, signifying a printer’s “stereotype block” upon which is etched a commonly used phrase, rather than just a letter.18 Derived from the past participle of the verb clicher, or to click, the term was connected to the sound made by a printing sort being set in place. Over time, cliché drifted semantically to its present-day meaning of a “trite, worn-out expression.”

Zhang extended this organizational scheme to practically the entire character rack, not merely a small, specialized region thereof as his colleagues had done. Zhang’s clichés were not consistent, moreover, but transformed depending upon the properties of the text under production and the overarching political environment.19 If “materials on the workers’ movement” constituted the operative theme of one period, Zhang explained, he prepared such compounds as “production” (shengchan), “experience” (jingyan), “labor” (laodong), and “record” (jilu). At other times, the demands of a specific propaganda campaign might dominate media attention, prompting Zhang to rearrange his character rack anew, prioritizing terms and phrases such as “Resist America, Aid Korea” (kang Mei yuan Chao) (the Korean War–era mass mobilization campaign).20 In this way, Zhang set about transforming his body and his character rack into Chinese Communist Party (CCP) rhetoric incarnate, not in the sense of parroting certain key terms, but in the sense that his fingers, hands, wrists, elbows, eyes, peripheral vision, joints, movements, anticipatory reflexes—every part of his body—would be intimately attuned and maximally sensitized to the distinct cadences of CCP rhetoric.

Zhang pushed his new character arrangement system further, surpassing his own record: a record 4,778 characters set in one hour, or nearly eighty characters per minute, captured on film on July 29, 1952, by the South Central Film Team of the Central Film Production Company.21 In the meantime, Party-state authorities saw in Zhang’s accomplishment an opportunity to celebrate the kind of proletarian parable so vital at the time: the model worker who had used personal initiative and free time to push his industry beyond what others had imagined possible, overturning “tradition” broadly writ, and in doing so demonstrating to the masses both the possibilities of ingenuity and the impermissibility of complacency.22 It was Zhang’s departure from conventional practice—his heteropraxy—that helped him serve orthodoxy far more effectively than rote, conventional practice—or orthopraxy—ever could. “One person setting three or four thousand characters [an hour] doesn’t amount to much,” Zhang reflected. “But if everyone were to set three or four thousand characters, now that’d be something.”23 In quick succession, the Party extended an invitation to the typesetter to take part in the May Day celebration of 1952, helped him to co-author a book explaining his method in greater depth, sponsored his tour of publishing houses across the country, admitted him to the Party, and encouraged others to study and perhaps emulate his method (figure 7.4).24

7.4 Zhang Jiying

The case of Zhang Jiying was soon followed by others. In 1952, Commercial Press in Shanghai undertook character tray reform, implementing the same lianchuanzi system and witnessing a clear increase in speed as a result.25 The Jinggangshan Newspaper Printing House implemented the lianchuanzi arrangement as well, as part of their shift away from the industry standard twenty-four-part character tray to the so-called “‘eight’-character-style” character rack (ba zi shi). And just as the city of Kaifeng had its model typesetter in Zhang Jiying, Jinggangshan could take pride in their own: local typesetter Wang Xinshun, who set an all-province hourly record on April 10, 1958, with 3,840 characters set. Wang broke his own record later that same year, setting 4,100.26

By 1958, lianchuanzi had become widespread enough to be spotlighted in a manual on page layout and typesetting published by the journalism research institute at People’s University.27 Here the method was referred to as the “Connected Language Tray Bed” (lianyu zipan) or the “Connected Character Tray Bed” (lianchuanzi zipan), and was explained as follows:

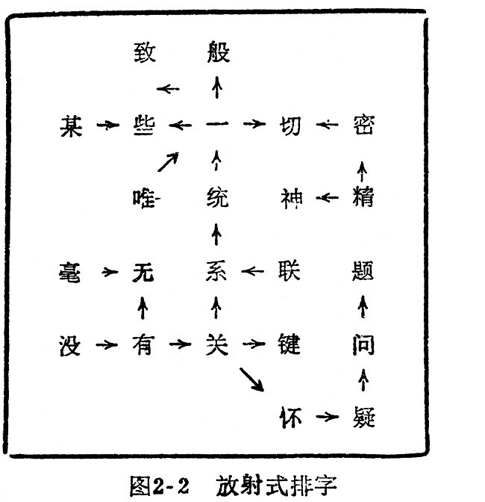

As much as possible, you want to place compounds together that are used together and are related—for example, by placing the four characters “jie” (解), “jue” (决), “wen” (问), “ti” (题) in four adjacent columns.28 Another example would be putting characters together like “jian” (建), “she” (设), “zu” (祖), “guo” (国), and “ti” (提), “gao” (高), “chan” (产), “liang” (量), which would make setting up these characters a lot more convenient.29 We could even consider using radiating style (fangshexing) or chainlink style (liansuoxing) to set up a common usage tray bed, for example “ren” (人), “min” (民), “gong” (公), “she” (社) —> “hui” (会), “zhu” (主), “yi” (义).30 Radiating it out like this would resemble the word game “thimble linking” (dingzhen xuxian).31

A similar technique, the manual explained, was to pair linked words and place them in thematic zones. In one zone, the typesetter might arrange clusters such as “American imperialism” (Meidi), “to invade” (qinlüe), and “to destroy” (pohuai), calling this the “negative connotation terms tray” (bianyi zipan).32 Another region could then be designated the “Social Structure Terms Tray” (shehui zuzhi mingcheng de pan), featuring, as the manual explained, “‘Socialism,’ ‘cooperative,’ ‘Chairman Mao,’ etc., etc.” (“shehui zhuyi,” “hezuoshe,” “Mao zhuxi” dengdeng).33

To find “Chairman Mao” and “socialism” tucked inside quotation marks, followed by the term dengdeng (“so on and so forth” or “et cetera”), is deeply revealing, alerting us to the metacognitive distance that was central to this organizational method. In order to make use of natural-language arrangements, one could not be an unwitting parroter of routine political expressions, spouting Mao-era phraseology unreflectively. To the contrary, one had to be acutely aware of their roteness and regularity—to think of them precisely as cliché, in order to be able to do an effective job of preparing one’s character rack or tray bed for maximum efficiency. The success of Zhang’s method was a function of maximum sensitization to and anticipation of the distinct cadences of CCP rhetoric, not just with obvious cases such as “Mao Zedong” and “cadre” (ganbu), but also politically charged “neutral” terms such as “education” (jiaoyu), “to exist” (cunzai), “according to” (genju), and others. It was Zhang’s ability to establish a deeply private, individualistic, even esoteric relationship with the public, authoritative, and standardized language of the era that increased his capacity to serve political orthodoxy. Radical individualism was, in this context, completely compatible with and conducive to state power.

As illustrated in the case of “New China Press,” Zhang Jiying was not the first to conceptualize a vernacular taxonomic approach to Chinese typesetting. He was, however, perhaps the first to pursue this possibility to its logical extremes, extending the lianchuanzi system across the entirety of the character rack, rather than a limited region thereof. The same distinction held true for Chinese typewriting, in which—as we recall from chapters 3 and 4—character slugs in the Chinese typewriter tray bed were not fixed, but rather removable and replaceable. Although the application of natural-language clusters achieved unprecedented stature and levels of experimentation beginning in the 1950s, in fact there were already limited “predictive” elements to the Chinese typewriters we examined from the Republican period. Two in particular merit consideration. First, we recall there existed one region on Republican-era typewriter tray beds reserved for “special usage characters” (teyong wenzi), in which characters were not organized according to radical classes or stroke count. Instead, within this narrow strip on the tray bed, measuring four columns wide and thirty-four rows deep, characters were clustered so as to form common two-character compounds and multicharacter sequences such as “the Republic of China” (Zhonghua minguo).34 In particular, typists dedicated this small region to the characters that formed the names of Chinese provinces. For example, the characters meng (蒙) and gu (古) were located horizontally adjacent to one another, forming the name Menggu or “Mongolia.” This arrangement became more complex and interesting in the case of characters that appeared in more than one toponym, such as jiang (江), hu (湖), nan (南), xi (西), dong (東), and shan (山) (figure 7.5). To the left of jiang, for example, was the character zhe (浙), forming the name Zhejiang; to its upper-left corner, the character su (蘇), forming Jiangsu; to its lower left was long (龍), beneath which was located a third character hei (黑)—together forming the province name Heilongjiang.35

7.5 Sample from “Special Character Region” of Huawen typewriter (pre-1928); from Chinese Typewriter Character Arrangement Table (Huawen daziji wenzi pailie biao) [華文打字機文字排列表], character table included with Teaching Materials for the Chinese Typewriter (Huawen dazi jiangyi) [華文打字講義], n.p., n.d. (produced pre-1928, circa 1917)

The second example comes in a letter dated August 26, 1928, from newspaper reporter, editor, and language reformer Chen Guangyao to Wang Yunwu, editor in chief at Commercial Press and inventor of the “Four-Corner” retrieval system we saw in the previous chapter. Knowing of the company’s Chinese typewriter division, Chen suggested to Wang the possibility of reorganizing the company’s Chinese typewriter tray bed so as to maximize the adjacency of naturally co-occurring Chinese characters. By way of example, Chen cited the two- and more-character terms “then” (ranze 然則), “China” (Zhongguo 中國), “to invent/invention” (faming 發明), “Three People’s Principles” (Sanmin zhuyi 三民主義), “world” (shijie 世界), and even longer idiomatic expressions like “to be unexpected” (yiliao zhiwai 意料之外).36 When ordering the characters in this way, he explained, a compression of only a few characters would make possible many more compounds. Even a simple four-character sequence 發明達光 made it possible to write such common terms as “to invent/invention” (faming 發明), “to develop” (fada 發達), and “bright” (guangming 光明), all with much greater speed and ease than when using radical-stroke arrangement. Moreover, common particles could be organized more scientifically by placing them, not in accordance with dictionary order, but in proximity to those characters alongside which they normally appeared.

For all his encouragement, however, Chen Guangyao’s experimental proposal to Commercial Press was never adopted by the company, and never took hold in other areas of Chinese typewriting. Indeed, within the rich archives on Republican-era typewriting, there is not a single further reference to the application of his system, whether in theory or in practice. To the contrary, all evidence suggests that, while elements of natural-language arrangement continued to be used on Republican-era machines, they remained entirely localized to the small “special usage” region of the typewriter.

The early PRC period marked a different era altogether. In the wake of the Zhang Jiying mini-phenomenon, natural-language organization was quickly appropriated from typesetting and applied to the field of Chinese typewriting. In November 1953, readers of the People’s Daily encountered Shen Yunfen, a young woman who had joined the People’s Liberation Army two years prior, at the age of seventeen.37 A native of Shanghai, she was appointed to the North China Military Region Headquarters to serve as a typist in October 1951 during the Korean War. By her own account, her performance was slow at the outset, which led her to experience despondence—even to the point of losing weight from the anxieties involved. Under the guidance of a colleague, Shen reported increasing her speed to 2,113 characters per hour—a respectable improvement, but one that left her dissatisfied.

Shen decided to pursue the “New Typing Method” (Xin dazi caozuofa), a method she had learned of recently, attributed to one Wang Jialong.38 Applying the same principle of adjacency as Zhang Jiying’s “serial” method, Wang and soon others exploited the shape of the typewriter tray bed to extend Zhang’s linear, one-dimensional organization into a two-dimensional, x-y matrix. The operative principle of the New Typing Method was termed “radiating compounds” (fuci fangshe tuan), explained as follows: by “selecting one character as the core and then radiating outward from it,” the typist could populate the three to eight spaces around each character with as many related characters as possible.39 Owing to this multidimensionality, the typist could push beyond the left-right sequencing of related characters on the compositor’s character rack, and begin to experiment with both vertical and diagonal arrangements. It also made possible the stringing together of these mini-regions into widening associative networks.

In moving away from radical-stroke organization, a space of practically infinite possibility was opened up. Shen Yunfen’s speeds steadily increased, reaching 3,012 characters per hour and then leading her to a first-place finish in the North China Military Region Typing Competition in 1953 with a record-setting 3,337 characters in one hour. On January 25, 1953, the young Shen was granted the title of “First-Class Hero” (yideng gongcheng) and “second-level model worker” (erji mofan). In September 1955, she was received by Mao Zedong at the National Conference of Youth Activists in Socialist Construction.40

An essential question emerges out of the stark contrast between Chen Guangyao’s failure in the Republican period and the vibrant experimentation of the 1950s: why was it only during the Communist period that this already known technolinguistic technique—“new,” “China,” “press”—became the object of intense focus and exploration? How did the logic of xinhuashe, a region accounting for only a fraction of the overall character rack, become the organizational principle for the entire character rack? Likewise, how did the logic governing a thin strip on Republican-era tray beds, a “special” region that accounted for not even 6 percent of the total lexical space, eventually conquer the surrounding 94 percent? One potential answer that can be disqualified immediately is any suggestion that the Republican period was in some sense less innovative, experimental, or anti-traditional with regard to language reform overall. To the contrary, as we saw in the preceding chapter, the late Qing and Republican periods witnessed a practically uninterrupted exploration of alternate character organization and retrieval systems, and scores of reformers heaped criticism upon the organization of the Kangxi Dictionary and its attendant radical-stroke system. Why then was it not until the 1950s that predictive text strategies began to proliferate within typesetting offices and on Chinese typewriter tray beds? How do we account for the sudden rise of natural-language experimentation in the Maoist period?

To understand the emergence of natural-language experimentation in the early Maoist period, we must consider three key political changes that took place following the Communist revolution of 1949: the Chinese Communist endorsement and celebration of what have been termed “popular” or “mass” knowledges; an increasingly routinized if not “predictable” Chinese Communist rhetoric; and unprecedented time pressure experienced by typists during the immediate postrevolutionary period.41 Just as Communist authorities made and endorsed radical pushes for nonelite participation in fields as diverse as paleontology, medicine, and seismology, so too did they endorse calls for a sweeping, bottom-up reorganization of the Chinese language—a mass taxonomy that would depart from earlier modes of categorizing Chinese characters, and better reflect the way in which “common people” organized their linguistic universes.42 If it was possible to proletarianize medicine and the physical sciences, and to “challenge the notion that science was the province of elites,” why not the systems by which script was organized?43 The second transformation involved the development of a political discourse of unprecedented routinization—a “systemization of ideological categories and language” that came to influence, if not define, entire domains of textual production in the early PRC period.44 This was true not merely for overtly Chinese Communist keywords such as “struggle” (douzheng) and “proletariat” (wuchan jieji), but also for an ever-expanding repertoire of what Franz Schurmann has aptly termed “seemingly conventional words with special significance”—terms such as “opinion” (yijian) and “discussion” (taolun).45 A third factor was the unprecedented employment of Chinese typists in the conduct of government affairs, a topic broached at the beginning of this chapter. By the mid-to-late 1950s, Chinese typists and typewriters could be found throughout China, serving an increasingly regular role in the everyday functioning of government, as well as in the unrelenting series of Mao-era mobilization campaigns—campaigns for which typists were tasked with producing economic reports and low-run mimeographed materials. During the Great Leap Forward, in particular, this increasing pressure on typists developed into a metanarrative all its own, with typists beginning to adopt the conventional language of “quotas” and “output.” Typists and work units competed with one another to outstrip target goals and to increase the efficiency of their “production”—that is, the total number of typewritten characters produced per month and per year.

These three novel conditions combined to catalyze the transformation of the tray bed into unprecedented linguistic configurations. The possibilities for such experimentation were practically boundless. With roughly 2,500 characters on the tray bed, typists had an unimaginably large number of different arrangements to try, making possible a total democratization of character organization in which each typist organized characters as he or she saw fit. More specifically, the possibility emerged of a system completely suited to two things simultaneously: one’s own body, including its deeply personal and varied idiosyncrasies of movement; and the increasingly standardized Maoist discourse of the period.

Having witnessed the celebration of Zhang Jiying, Shen Yunfen, and other model taxonomists in the popular press, we might be tempted to imagine that Party, state, and industry elites saw the virtue of this new, decentralized taxonomic experiment and encouraged the nation’s typists to stride forth toward this brave new future. What transpired was something altogether different. Party and industry elites may have celebrated Zhang Jiying, but ultimately they had little faith that his methods could be adopted in any widespread manner by Chinese typists. Zhang and Shen were models, to be sure, but not ones that Party and industry leaders believed it possible for all compositors and typists to emulate. Rather than lending support to further user-led experiments in vernacular taxonomy, the early Mao-era typewriter industry instead set off down a path common to other branches of media in the early PRC: centralization. Specifically, they set out to standardize and centralize this new phenomenon of vernacular taxonomy.

We gain insight into the minds of early PRC typewriting circles through the minutes of a 1953 meeting held in Tianjin. At the “Meeting for the Improvement of the Typewriter Character Chart” (Xiugai daziji zibiao huiyi), fifty-two representatives convened on August 30: representatives from manufacturers, typing schools, the Tianjin City Committee of the CCP, the Tianjin municipal government, and some thirty other work units. Here participants reflected upon the recent past of the Chinese typewriter industry, and their visions for its future.

The preeminent concern among participants was the problem of standardization. There were problems with the Chinese typewriter, one participant argued, “with regard to the old tray bed, as well as the selection and arrangement of characters. These have adversely affected the improvement of the efficiency of the typewriter.”46 More broadly, complaints were expressed about the general lack of standardization across typewriter manufacturers, noting that each manufacturer used a different character layout chart. In an age of standardization and rationalization, such a tendency could hardly be permitted to continue unchecked. Cited favorably at the meeting was the Party’s campaign to simplify Chinese characters and to abolish “variant characters” (yitizi).47 If a comparable level of standardization could be brought to bear within Chinese typewriting, participants agreed, the positive effects would be manifest. Once Chinese typewriter tray beds were set up in a unified way, for example, editors could in turn publish character indexes and typing textbooks to be used by one and all. “This would be extremely helpful for both study and usage,” as one participant summarized.48

The typing reform committee in Tianjin was well aware of the experiments then underway with vernacular taxonomy, moreover. They just did not imagine them implementable across a wide community of practice. In their reports they referred to these as “radiating compounds” (fangshe zituan), defined as “taking one character as the core, then arranging specially related compounds to the top, bottom, left, and right.” Offering a measure of praise for the system, the committee was also quick to outline no fewer than three problems with it. First, it provided no “set sequence” (yiding de cixu), relying instead upon “rote memorization and groping around” (qiangji mosuo). Second, because Chinese characters connected with one another to form an exceedingly large number of compounds, the radiating method could hardly hope to achieve comprehensiveness. The third and most critical problem, however, was its unmistakably idiosyncratic and individualistic quality. Were a typist using such a method to depart her post, or were a clerk to fall ill, it would prove difficult to replace her. This system would not suffice, it was decided—it was not “absolutely good.”49 In sharp contrast to the stories of Zhang Jiying, Shen Yunfen, and others, a core principle came to be shared by those in attendance at the Tianjin meeting: Chinese typewriters should maintain the industry standard radical-stroke system of organizing characters.

As if in consolation, however, the committee did put forth its own, far more moderate proposal for the tray bed. Within a given radical class, the sequence of characters need not adhere strictly to stroke count, they conceded. If two characters within a given radical class tended to appear together in Chinese words or phrases, it was reasonable to organize them adjacently on the tray bed—even if this meant violating stroke count.50 The earliest manifestation we encounter of this “relaxed” radical-stroke tray bed was the Wanneng (“All-Purpose”) Chinese Typewriter, manufactured circa 1956—the machine once built by Japan, but now under control of Chinese manufacturers.51 Far more reserved than Zhang Jiying’s character rack, this tray bed featured what can be thought of as at most an “adjustment” rather than abandonment of the radical-stroke system: radical classes were maintained, but within them characters could be placed out of order in terms of stroke count.

A sign of the Wanneng’s partial loosening of organization can be seen when we look at the characters categorized within the “water” radical. Directly to the left of the character ze, we find mao: the typist could thus proceed directly between two of the three characters that formed the name of the Great Helmsman, Mao Zedong. At the same time, the third character in Mao’s full name—dong, meaning “east”—was located where it tended to be located on all typewriters to date: in the “special usage” region, positioned alongside the three other cardinal directions. With the Wanneng machine, then, we encounter the industry’s first response to the bottom-up experiment with vernacular taxonomy. Unwilling to break with the radical-stroke system, typewriter manufacturers and industry leaders instead put forth a compromised vision in which typists would have to content themselves with refinements only slightly more suited to the rapid production of common compounds and names. At the same time, industry leaders cautioned that even this relaxation in the radical-stroke system needed to be undertaken slowly, and that it would take users time to learn. While a limited amount of individual personalization was “feasible” (kexingde),52 the Tianjin committee noted, “it’s best not to make any more big changes” (zuihao buyao zai da gaizhuang).

No doubt challenged and inspired by local-level experiments well underway by the mid-1950s, the typewriting industry decided to undertake a slightly more dramatic departure: the “Reformed” Chinese typewriter of 1956, which constituted the first machine to be outfitted with an “out-of-the-box” natural-language tray bed. In this tray bed arrangement, radical-stroke taxonomy was no longer obeyed, with the manufacturer instead developing its own vernacular arrangement based upon the same principles then circulating among everyday users.53 In one sense, this move constituted an endorsement of local-level experimentation, while at the same time, it redoubled the industry’s commitment to centralization and standardization. On this machine, the arrangement of Chinese characters would be subordinated not to the body of any individual typist per se, but instead to that of a hypothetical, average typist to be defined by the manufacturer itself—a kind of homme moyen not unlike those we encountered in chapter 6. Once this transition to vernacular arrangement had been made, presumably, textbooks could continue to be edited and published en masse, as could character tray bed charts. Once incorporated into typing institutes and programs, moreover, typists could be expected to memorize this new layout precisely as they had the earlier radical-stroke system. Phrased differently, the industry attempted to standardize the vernacular, exhibiting the same impulse as Chinese elites in the first half of the twentieth century during the country’s first and more famous vernacularization movement.

Manufacturers may have been content to stop at the “reformed” tray bed, but typists were not. In a historical development that further highlights the importance of user-driven technological change, individual Chinese operators pushed nascent ideas of tray bed reorganization toward what in many ways was its logical extreme: a total democratization of character organization in which each typist organized his or her tray bed as he or she saw fit, in accordance with the many particularities of his or her own, individual body.54 There would be no standards, no centralization, and, indeed, effectively infinite potential variation (with 2,500 characters being amenable to approximately 1.6288 × 107528 different arrangements).55

In this sense, Chinese typists took centrally issued propaganda about “model typists” and “model typesetters” more seriously and literally than central authorities had anticipated, creating machines that were at once deeper extensions of their bodies into Chinese Communist rhetoric, and deeper ingestions of this rhetoric into their bodies. Departing entirely from the radical-stroke system, and from the dictates of any centrally authorized taxonomic “starting point” to the tray bed, the goal became the development of organizational systems completely suited to one’s own body and to the discourse of the Maoist period. What ensued was the development of a practically infinite number of deeply personal pathways to an increasingly rote, standardized political discourse. By means of this comprehensive subordination of the machinery of language to the body—not to one centrally determined, hypothetical body, but to all bodies, democratically, empirically, and privately determined—what became possible was a more perfect and ever more personal connection and commitment to the rhetorical apparatus of Maoism.

Confronted by dizzying possibility, typists hardly engaged in blind or random rearrangements of characters. There was an emerging logic to vernacular taxonomy, as well as an emerging community of practice in which one could share and learn principles. Indeed, decentralized, user-driven reorganization became so important within Chinese typewriting that, beginning in the 1960s, we begin to see a formalization of natural-language experimentation—an attempt not to centralize it, but to set down certain “best practices” in writing. In a fascinating explanation of natural-language tray bed arrangements from 1960, authors Wang Guihua and Lin Gensheng drilled down into the question of how one should go about setting up a vernacular tray bed.56 They outlined for their readers the different factors that influenced when one should undertake such a renovation, as well as certain spatial-linguistic factors that should be kept in mind during the process.

The authors contrasted two strategies for setting up a vernacular machine: “gradual improvement” (zhuri gaijin) and “all-at-once rearrangement” (yici gaipai). Gradual improvements of the tray bed, they explained, involved making incremental changes each day, taking careful notes about which characters one used more and less frequently, selectively moving these higher- and lower-frequency characters around the tray bed, and taking detailed notes about any changes one made. “Gradual improvement” was ideally suited to work units with only one typist, Wang and Lin suggested, because it would minimize disturbance to the unit’s workflow, and because the redistributed characters would be simpler to remember. There were disadvantages to the method, however. With more than two thousand characters on the tray bed, it could take an exceedingly long time to complete the process—as long as a year if one changed between six and seven characters every day. Perhaps most importantly, the gradual method was unsystematic, since it was carried out in piecemeal fashion. The typist in this method did not engage in extensive preparation or consideration, thereby raising the risk of making poor taxonomic decisions that, while seemingly appropriate at first, could later prove detrimental and difficult to remedy.

The “all-at-once” method was a more extreme alternative. After extensive mapping and planning, the typist would use his or her spare time to empty the tray bed completely, and then build it back up, cell by cell, in accordance with a carefully determined lexical blueprint. In a single, concerted exertion of mental and physical labor, the process could be completed in its entirety. An all-at-once transformation incurred obvious risks, however. First, it placed a tremendous onus on the typist’s memory, requiring him or her to memorize an entirely new organizational layout right away (a challenging task, even if we are speaking of a system that the typist would have developed personally). To cope, Wang and Lin explained, it was advisable for the typist to spend his or her spare time memorizing the new layout as rigorously as possible, once the new layout was established. Either the whole arrangement had to be memorized from day one—an improbable feat—or the typist’s productivity and speed would necessarily suffer for a period of time. As such, this method was less advisable than the “gradual method” for work units that relied upon a single typist. “Rearranging a tray bed must be done with care and attention, and assiduously,” Wang and Lin summarized. “You must not engage in such a thing carelessly. But at the same time, you must overcome all kinds of conservative thinking.”57

Wang and Lin also provided a detailed overview of the best systems one could use, focusing on five spatial-linguistic approaches in particular: association style, radiating style, fortress style, connecting verse style, and repeating character style (chongfuzi shi).58 Within association style (jituanshi), the typist started by placing a character within the tray bed matrix, and then surrounded it on all sides with related characters—building further associative clusters from there, using each of those characters as a new starting point. The example given by the author was that of shi (时), indicating “time” in a general sense. With this character as epicenter, a typist using association style would then surround it with characters such as ping (平), tong (同), ji (及), zan (暂), xiao (小), sui (随), lin (临), and so forth. Each of these characters, when concatenated with shi, formed common two-character Chinese words: “normally” (pingshi), “at the same time” (tongshi), “timely” (jishi), “hour” (xiaoshi), “at a time of one’s choosing” (suishi), and “temporarily” (linshi). In fortress style (baoleishi), by comparison, the typist combined place names, personal names, or technical terms in one dedicated zone of the tray bed, even if these terms could not be combined with one another to any significant degree. One simply knew in this technique that all country names, for example, were to be found in the lower right zone of the tray bed, whereas personal names were to be found in the lower left.59

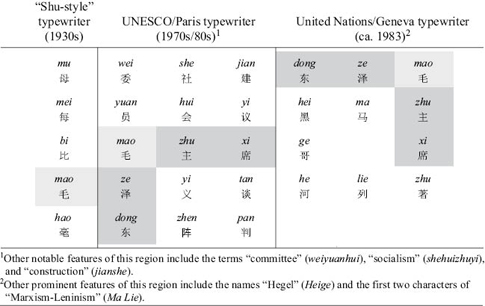

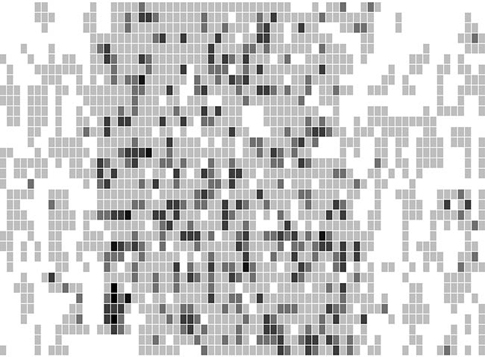

The principles outlined by Wang, Lin, and others were adopted and elaborated upon by typists throughout the Maoist period, and indeed beyond. From the evidence of two machines manufactured in mainland China, and used by mainland Chinese typists during the 1970s and 1980s in two separate locations—the United Nations in Geneva, and the offices of UNESCO in Paris—we discover both shared patterns and idiosyncratic differences that reveal the factors and strategies guiding this vernacularization movement.60 As these examples illustrate, these typists were engaged in ongoing, situated processes of “tinkering and making ad hoc arrangements” and “reconfigurations” not unlike those described in other user-machine contexts examined by Adele Clarke, Joan Fujimura, and Lucy Suchman.61 Starting with the character mao (as in “Mao Zedong”), we can juxtapose each of these two machines against one another and against a machine from the pre-Communist period configured according to radical-stroke arrangement (figure 7.6).

7.6 The location of the character mao (毛) on three Chinese typewriters

As shown here, the character mao was arranged according to the radical-stroke system on the Republican-era machine, just above the character hao (毫) built out of the same “hair radical” component (毛). On the UNESCO and UN machines, by contrast, the placement of the character mao makes clear that these two typists were weighing an entirely different and new set of considerations. Rather than placing the character where it belonged within the radical-stroke system, the UNESCO typist placed mao within a specifically political configuration: directly above the characters ze (泽) and dong (东) (forming Mao’s full name); and directly to the left of the characters zhu (主) and xi (席) (forming “Mao zhuxi” or “Chairman Mao”). Owing to this rearrangement, the production of the name “Mao Zedong” on the UNESCO machine now required the operator to traverse only two units of space. By comparison, the same three characters typed on the popular Commercial Press machine of the 1930s would have required the user to traverse some 57.66 units of space: from mao at (34,37) to ze at (54,5), and finally to dong at (35,11). A survey of the tray beds reveals hundreds of other similar examples, including “Chairman Mao,” “committee member” (weiyuan), “independent” (duli), “plan” (jihua), “to attack” (gongji), and “nationality” (minzu).62

When considered collectively, all of these small changes added up to something revolutionary. If we visualize two tray beds as heat maps—one tray bed from the Republican period, and one from after the move to natural-language arrangements—we can begin to appreciate the consequence of this new form of classification (figure 7.7).63 In these heat maps, the color of each cell is a scaled chromatic representation of the number of adjacent characters with which a given character can be combined to form a real, two-character word, with white equaling 0 (indicating that a character cannot be meaningfully combined with any adjacent characters) and shades of light to dark gray corresponding to the range of values between 1 and 8 (8 indicating that a character can be combined meaningfully with all of its adjacent characters). Looking at them, we witness the “predictive turn” in Chinese information technology—a revolutionary vernacularization of taxonomy that formed the conceptual and practical foundations of what we now refer to as “predictive text.”

7.7 Heat map comparison of typewriters from before and after the predictive turn

As illustrated in this visualization, Mao-era experimentation with the Chinese typewriter resulted in a significantly “hotter” tray bed, one in which only a very small proportion of characters were not located next to at least one other character with which they tended to appear in natural language.

A further comparison of the UNESCO tray bed visualization with that of the UN machine—that is, between two machines which both employed predictive text organization—is equally revealing, alerting us to the dramatically decentralized and democratic dimension of this experimental movement. Although the goal was to produce more perfectly the rote and repetitive nature of phraseology within Maoist China, each tray bed was utterly individual and personal (figure 7.8).

7.8 Heat map comparison of two natural-language tray beds

There was an immense space for individualization within this practice, that is to say, with many factors to consider beyond those of vocabulary. To create a predictive text tray bed, one had to determine which characters to include on the tray bed; which two-, three-, and four-character sequences to make adjacent; where and how to create these adjacencies; where on the tray bed to place the centermost character (so as to avoid crowding or bunching up); how to place certain “dead-end” characters that were limited to only very specific two-character pairings (such as the jin of Tianjin, which pairs with few other characters); and how to shape the directionality of these pairings, among many others. There was also quite likely a mnemonic dimension to predictive text tray beds—that is, the ways in which typists would have used associative clusters not only to accelerate the speed of typing, but also as an aide-mémoire for the location of specific characters within specific clusters (for example, remembering the location of the character mei—美 “beauty”—by remembering that it formed part of the cluster Mei diguo—美帝国 “American imperialist”). To produce a predictive text tray bed was no simplistic matter of regurgitating rote phraseology, but a profoundly subtle “memory practice.”64

By the close of the 1980s, natural-language arrangements had become so popular among typists that typewriter manufacturers began providing consumers with blank tray bed tables. Rather than printing conventional tray bed guides—guides that, since the 1910s, had mapped out the precise location of every one of the roughly 2,500 characters on the machine—these new manuals included a tray bed table left purposefully blank, providing users with nothing more than “suggestions” as to general principles of natural-language organization (figure 7.9).65 Still other manuals provided more detailed recommendations on how to conceptualize a natural-language arrangement, but again left it up to individual typists to determine exactly how they would implement the system on their devices (figure 7.10).66

7.9 Predictive text tray bed organization chart (1988)

7.10 Explanation of “arrow style” organization in 1989 typewriting manual

Once eager to standardize and centralize these new experimental efforts in the domains of typesetting and typewriting, publishers and companies were now capitulating to local-level, user-led changes, spending the waning years of the Chinese typewriting industry trying to catch up along a path that had already been forged by the “masses.”