Out of the melting pot of the emerging American culture came the sounds of a new theatrical art form brimming with Yankee confidence and rhythmic ingenuity. From the streets of New York City—seething with the clashing tensions of immigrant dreamers determined to make for themselves a better life—a dissonant new tempo of both rebellion and individuality was rising up through the popular songs of Tin Pan Alley, and those songs were starting to land in stage shows.

Ragtime rhythms drove the finger-snapping melodies, composed by a newer breed of tunesmiths who now competed head-on with established, classically trained composers from abroad—composers whose staid operettas reflected that old world left behind. A steady succession of novice American songwriters knocked upon the doors of popular music publishers like Max Dreyfus, president of T. B. Harms and Co., who could send a promising talent into career orbit overnight. In publishing offices all around the district, theatrical producers came to listen to new tunes for possible insertion in their upcoming shows. Songs were needed for singers and specialty acts, as well as to “Americanize” imported British operettas to make them more appealing to local ears.

As the new American century dawned, no single figure better expressed this bold new songwriting dynamic than master showman George M. Cohan, father of the modern Broadway show tune. Born on the fourth of July in 1878 to an Irish family of traveling stage entertainers—the Four Cohans, “America’s Favorite Family”—Cohan followed his destiny across the stages of vaudeville, where he acted, danced, strutted in blackface and sang, wrote, composed, directed and produced. At the age of 13, the plucky young egotist broke out on his own, landing a lead role Peck’s Bad Boy (in which he was clearly a hit) and getting a taste of solo celebrity. Rapidly ascending the neon ladder to stardom, Cohan brought crowd-pleasing gusto to the fledgling art of American musical comedy.

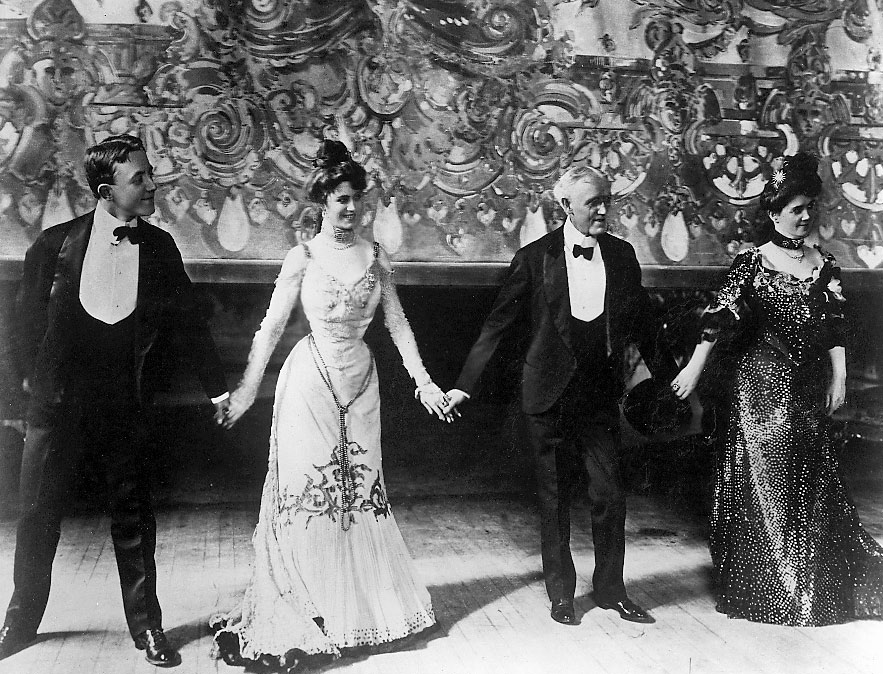

Raised on vaudeville: George M. Cohan (left) with (left to right) sister Josie and parents Jerry and Nellie in the family act.

Cohan launched his legendary contribution—a virtual new song template—in his third musical and first hit, Little Johnny Jones, a 1904 venture that lasted less than two months at the old Liberty Theatre, but which, after major revisions, played twenty more weeks in New York during two repeat engagements the following year. Cohan himself introduced the ground-breaking number in the role of the American jockey Johnny Jones, returning victoriously to his home town after being falsely accused of throwing a race at the London Derby.

Give my regards to Broadway,

Remember me to Herald Square;

Tell all the gang at Forty-Second Street

that I will soon be there!

Whisper of how I’m yearning

to mingle with the old time throng;

Give my regards to old Broadway

and say that I’ll be there, e’er long.

The opening night house went wild with applause, refusing to stop until Cohan turned, bowed, and offered a few words of thanks. It was a turning point for Broadway and for its new star, who would go on belting out songs from his heart, songs characterized by Brooks Atkinson as “sublimations of the mood of their day. They said what millions of people would have said if they had Cohan’s talent.”1

On the serious side, Cohan expressed a humble philosophy of life that enamored him further with his working-class fans:

Did you ever sit and ponder

Sit and wonder,

Sit and think

Why we’re here and what this life is all about?

It’s a problem that has driven many brainy men to drink

It’s the weirdest thing they’ve tried to figure outAbout a thousand different theories

The scientists can show

But never have yet proved a reason why

With all we’ve thought and all we’re taught

Why, all we seem to know

Is we’re born, live a while then we dieLife’s a very funny proposition after all

Imagination, jealousy, hypocrisy, gall

Three meals a day

A whole lot to say

When you haven’t got the coin,

You’re always in the way …

And how fleeting were Cohan’s gifts for connecting with the mood of the day: Within a mere four-year stretch, all of his songs destined for fame were introduced to Broadway. In his autobiography, he described the upbeat ditties as “ragtime marches,”2 suggesting (rightly) that his inventions sprang from black music. Almost every composer who subsequently achieved success in musical theatre would pay tribute one time or another to Cohan’s ragtime marches. Oscar Hammerstein would one day remark, “Never was a plant more indigenous to a particular part of the earth than was George M. Cohan to the United States of his day. The whole nation was confident of its superiority, its moral virtue, its happy isolation from the intrigues of the old country, from which many of our fathers and grandfathers had migrated.”3

Dubbed by Gerald Bordman “America’s first musical comedy genius,”4 the multi-talented Cohan, who contributed to 21 musicals and 20 plays, pioneered the natural transformation of vaudeville into song-and-dance shows with scripted characters and story lines, however lightweight. His pulsing tunes and swaggering street-wise attitudes offered refreshing counterpoint to the more sedate operettas with their ponderous romantic tales played out by castle-dwelling characters of privilege. A strident non-elitist, George M. played as much to the lower classes up in the balconies as he did to the carriage trade down in the orchestra. His shameless flag waving shtick, though frowned upon by critics, was loved by the common man. In fact, the song-and-dance king found greater popularity on the road than he ever did in New York City.

Cohan would inspire a whole new generation of popular American stage composers. Among them was Jerome Kern, who came up through the pop trenches like most of his peers, starting off as the recipient of numerous rejections from music publishers. Then in 1902 came a note from Edward B. Marks’s Lyceum Music Publishing Company with news that it was about to publish Kern’s piano tune “At the Casino.” The novice was only 17 when the name “Jerome D. Kern” first appeared on sheet music.

This led to his becoming a song plugger at Marks’s company for $7 a week. Later he performed clerical duties for the smaller T.B. Harms publishing firm, run by Max Dreyfus. Dreyfus would work wonders for many young composers, handpicking virtually every early-century tunesmith destined for musical theatre fame. For Kern, however, there was no such magic. Working for Dreyfus, he advanced only as far as sheet music salesman.

Impatient for songwriting opportunities, Kern threw his fate to the Brits. Shrewdly aware of the West End’s dominance over New York, he journeyed to London and was soon composing throwaway songs for the humdrum first half-hour segments of stage shows, which were largely ignored by blasé late-arriving patrons.

In time, Kern’s numbers were too good to ignore. And when finally his career took flight, Jerome Kern took a pioneering interest in the potential dramatic function of a song, longing to elevate its relevance in stage shows. Songwriters of the day, as remembered by Otto Harbach, “paid almost no attention to plot. They were indifferent to characters, even to the situations in which their songs were involved. They didn’t care much about the kind of lyric that was being written for their melodies, just as long as the words could fit the tune.”5 Kern took a giant step in another direction when he joined forces with lyricists Schuyler Greene and Herbert Reynolds, and librettists Philip Bartholomae and Guy Bolton, to create for the 299-seat Princess Theatre the first of several small-scale musicals, the enthusiastically received Very Good Eddie. The buoyant little tuner contained a high-voltage set of razzmatazz, finger-snapping songs with none of the maudlin sentiment of the starchy operettas of old Vienna. The show’s smart topical lyrics opened a door to the jazz age just ahead.

Eddie portrayed a chance encounter between a man and a woman, each embarking on a honeymoon voyage up the Hudson River, but by accident without their respective spouses. They come to find they are better suited to each other than to the loves they left behind. Insecure Eddie Kettle, thinking unhappily of his very tall, very domineering new wife back there on the dock, laments his embarrassing plight, courtesy of words by Schuyler Greene:

When you wear a nineteen collar

And a size eleven shoe

You can lead a pirate through

Smoke and drink and swear and chew

But you have to lock ambition up

And throw away the key

When your collar’s number thirteen

And your shoes are number three!

Faithful to the production restraints of a Princess Theatre show, Very Good Eddie was confined to two sets; its locale was American; the theatrical muse it served was light comedy, and its cast did not exceed thirty in number. How to top its ebullient charms? Kern and Guy Bolton, along with P.G. Wodehouse, came back a couple of seasons later with the similarly styled Leave It to Jane, a college musical centered around a football game between two rival campuses. Jane snares her school’s star football player in order to keep him from deserting to the other school. Kern’s breezy score overflowed with more melodic delights. Wodehouse atypically wrote all the lyrics, supplying ample wit to such novelties as the worldly “Sir Galahad” and the clever “Cleopatterer.” In the category of pure heart-raising charm, there was the show-stopping “The Sun Shines Brighter.” Oddly, Jane, although in spirit a Princess Show, played the Longacre Theatre, possibly a bad move. Its run was half that of Eddie.

Kern and Wodehouse, numbered among the boldest innovators, daringly introduced ragtime, and they turned their backs on the sullen and somber operettas of Rudolf Friml, Victor Herbert and Sigmund Romberg, transplanted European-born composers who sold the stuffier images of a distant upscale culture to New York theatergoers. The younger generations naturally strove to shake things up, to bring a new sound into playhouses. Harry Tierney, another Tin Pan Alley pro, scored a huge 670-performance success in 1919 at the Vanderbilt with Irene; yet he mixed together a diversified score of older style refrains like “Alice Blue Gown” and modern work such as the jazzy “Sky Rocket” and the zesty “Hobbies.” The Times’ notice promised more than a silly surfeit of “girls and music and jokes and dancers and singers…. [Irene] has a lot of catchy music…. Also it has a plot.”6

The new American songsmiths followed a commercial path by which virtually all show composers of the time honed and shaped their talents. Either they proved adept at reaching a mass public or they languished. Those who delivered the goods were invariably offered opportunities to have their most commercial numbers included in stage shows. Irving Berlin, another newcomer on the block, had been pitching his talents along Tin Pan Alley, too—first in the role, along New York streets, of a singing panhandler; next, as a singing waiter at a saloon in Chinatown; then as the lyric writer, in 1907, of his first published song, “Marie from Sunny Italy,” with music by Nick Nicholson. In 1908, at the age of 20, Berlin started supplying his own music with “Best of Friends Must Part.” He went to work for publisher and songwriter Ted Snyder, turning out mostly the words, as he would do for several years. Soon, Berlin became a partner in the firm, and he began getting his songs interpolated into musicals. Berlin’s big break came when a lyric he wrote to a Ted Snyder tune, “She Was a Dear Little Girl,” landed on Broadway in The Boys and Betty.

Within a couple of seasons, Berlin found producer support from Florence Ziegfeld, in whose lavish Follies his songs were famously received, and growing public favor in his lyric contributions to a steady succession of shows, some stateside, some abroad—among them The Sun Dodgers, Hullo, Ragtime, and The Trained Nurses. For the latter, a vaudeville act produced in 1913 by Jesse Lasky, Berlin composed and wrote “If You Don’t Want Me (Why Do You Hang Around?)”

Watch Your Step, with Irene and Vernon Castle, which Charles Dillingham produced at the Globe Theatre in 1914, marked Berlin’s first full score. Billed as a “syncopated musical,” Step was considered a forerunner to the more pop-oriented musicals of the day which would follow. It held on for a handy 175 performances, and out of its 24 plus numbers, only one remains a standard: “Simple Melody.”

Simple salty melodies. First pounded out on big old uprights in Manhattan. Pounded out to impress jaded Tin Pan Alley tycoons—characters like legendary Max Dreyfus, who spotted true talent as naturally as bees spot flowers and then goaded producers into taking chances on his untried finds and their unknown songs. King melody makers they became, selling the best to a demanding public. Theatergoers expected to whistle the refrains—not the scenery—on their way out of the New Amsterdam and the Winter Garden and the Globe.

Seven seasons later, Irving Berlin realized a fine stateside success with the first edition of The Music Box Revue, this one shipshaped into breezy perfection by director Hassard Short. Out of the show came another Berlin classic, “Say It with Music.” And from the John Murray Anderson directed Music Box Revue of 1924, headlining Fanny Brice and Bobby Clark, came “All Alone,” first sung earlier the same year at the Duke of York’s Theatre in London in the rousing success The Punch Bowl.

Hundreds of memorable songs would first be introduced to America in hundreds of ultimately forgotten shows. During the 1920s, New York stages hosted over two hundred new legit productions each season.

Never to be forgotten was the syncopation-mad 1924 triumph Lady Be Good, a rousing culmination of Roaring Twenties sensibilities and the new American musical comedy show—all on the same stage at the same time. Lady also marked the coming of age of its young, restless composer, George Gershwin, who was now starting to dazzle the city’s carriage trade with a rare kind of infectious, hyperactive music. Gershwin, a Max Dreyfus discovery, had displayed composing talent when he was an eleven-year-old lad who, away from a piano, rolled on fast wheels over some of New York’s toughest streets, winning roller-skating speed contests. By fifteen he quit school to take a job plugging songs for music publisher Jerome H. Remick. Young George made money producing player piano rolls. His first song, “When You Want ’Em, You Can’t Get ’Em,” with words by Murray Roth, was published in 1916. The year before, at age 17, he had made his debut on Broadway at the Winter Garden Theatre with a single contribution: “The Making of a Girl,” which made it into The Passing Show of 1916—with a little help by an opportunistic young Sigmund Romberg. Romberg, then a lowly staff composer for the Shubert Organization, had taken a liking to Gershwin’s compositions. He asked the book and lyrics man for The Passing Show, Harold Atteridge, to write words for one of Gershwin’s melodies, after which Romberg took co-credit for the music.

Three years later, the adaptable George Gershwin found a more lucrative partnership with lyricist Irving Caesar when the two fashioned a song for the live pre-movie revue at the Capitol Theatre movie palace. In attendance one night was Al Jolson, who fell in love with the number and subsequently recorded it as Gershwin’s first major hit, “Swanee.”

Gershwin was now selling his songs to a number of theatrical producers and music publishers, most notably to several editions of George White’s Scandals, whose 1922 version, with W. C. Fields in the cast and Paul Whiteman directing in the pit, featured Gershwin’s second hit song, “I’ll Build a Stairway to Paradise.” His biggest break followed in 1924, when he suddenly acquired a talk-of-the-town reputation following the first performance of his groundbreaking symphonic jazz work composed for orchestra, “Rhapsody in Blue.”

Later the same year George teamed up for the first time with brother Ira, a fine lyric writer, to create the solidly tuneful hit Lady Be Good. Ira’s savvy words rode George’s frenetic tunes with smart devotion.

Indeed, by 1924, in the district known as Times Square, the tunes of Tin Pan Alley were beginning to hold their own against the more conservative refrains of operettas (both imported and created afresh). Lady followed the recent openings of Andre Charlot’s Revue of 1924—composed by, among others, Noël Coward, Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle (“Limehouse Blues”)—and the Rudolf Friml, Oscar Hammerstein and Otto Harbach smash, Rose Marie. And it was followed, the very next night, by the opening of another old-time crowd pleaser, Sigmund Romberg’s Student Prince. Unlike its stodgy formulaic competitors heavily laden with brooding love songs, Lady Be Good offered virtually no ballads. The George and Ira Gershwin romp danced on Jazz-age gusto—numbers like “Hang On to Me,” “So Am I,” and “Insufficient Sweetie.” The kind of “excellent” tunes which, according to the New York Times reviewer, “the unmusical and serious-minded will find it hard to get rid of.”7

The score’s crowning centerpiece was “Fascinating Rhythm,” the song which would forever symbolize the driving syncopation of the new American tuner. And it launched Gershwin’s genius in the public’s imagination. He and Ira would collaborate on fourteen shows over a brief eleven-year span. Music is mostly what they would be remembered for.

Lady Be Good was technically a “book” show—credit Guy Bolton and Fred Thompson for whatever narrative sense it conveyed, accidental or otherwise. The fragile story line told a then-typical rags-to-riches tale wherein true love overcomes class distinctions, Cinderella style. An evicted brother and sister living on the streets land a job entertaining at a rich estate. Each becomes romantically entangled through rather trite, implausible plot complications—the brother ending up in marriage to a common girl, the sister, alas! to a millionaire—and the show serves up four happy weddings by final curtain. The brother and sister were played by a bright new song and dance team just returning from starring spots in a London hit, For Goodness Sake, and for whom the whole affair had been tailor-made—Fred and Adele Astaire.

Left to right: Ira Gershwin, brother George, and librettist Guy Bolton.

Who could ask for anything more? The New York Times critic did, suggesting it needed more humor. Overall, however, the scribe was amply impressed, describing Lady Be Good as “a drama of outcasts, rents, social shinning, loving resolutions and well-ending marital fortunes,” praising Adele as a new Beatrice Lillie, and favoring the paper-thin libretto because it favored Adele: “The book of the piece contains just enough story to call Miss Astaire on stage at frequent intervals, which thus makes it an excellent book.”8 Meanwhile, the beguiling beat of Gershwin’s frenetic score rattled on like a Gotham subway train.

Gershwin the speed skater rarely slowed down at the piano. Why no slow numbers in Lady? Considering its preoccupation with pace, how easy it is to imagine director Felix Edwards fearing that a single moment of letup might reveal a certain lack of substance. And easy to imagine choreographer Sammy Lee holding out, in full accord, for nonstop Gershwin zip. Edwards and Lee may have waged an out-of-town campaign to nix any and all beautiful refrains. “The Man I Love”—yes, that lustrous Gershwin gem—was deemed not right for Lady Be Good. Dropped on the road. The flapper era had scarce patience or time for introspective ballads.

Instead, producers pushed for foot-stomping pizazz, the more the better. And across the Atlantic, when the show took a tour of London, George and Ira added a brand new number—yet another blast for dancing feet, “I’d Rather Charleston.” The Gershwin brothers, perfectly in sync with the Roaring Twenties, had a bona fide smash at the Liberty Theatre, where Lady Be Good played for 330 performances. Ira’s nimble verse added a sophisticated gloss to George’s clattering refrains—though a noticeable dearth of comedy verse foreshadowed Ira’s principal shortcoming. No ballads. No funny songs. Just heart-pounding melodies and nimble carefree words.

While the Gershwins were celebrating their first stage success, other newcomers who would eventually achieve similar status were still struggling for the Big Break. Cole Porter, for one. Another name not very well known—not yet—Mr. Porter was one of the many random, nearly faceless contributors to Follies. The native of Peru, Indiana, had only one hit tune to his credit, the quaintly sentimental “Old Fashioned Garden.” He had written it for a 1919 flop, Hitchy Koo, built around the comic talents of Raymond Hitchcock—not funny enough to rally the crowds beyond a few weeks on the boards.

Porter had been struggling for success since 1915 when his first song to reach Broadway, “Esmerelda,” went down with the inglorious Hands Up. Regrettably, that success had proved more elusive than the pleasures of the high life to which he had become gracefully addicted. The son of a well-heeled family, Porter served the briefest possible stint on Tin Pan Alley—long enough to sell a single number in 1910 entitled “Bridget.” Ironically, two of the songs he composed for the famed Greenwich Village Follies of 1924, “I’m In Love Again” and “Two Little Babes in the Wood,” were both destined to become popular several years after Porter’s first stage success opened.

Mr. Porter, a Yale man who had specialized in composing songs for varsity revues and football games (“Bulldog, Bulldog! Bow! Wow! Wow!”), upon graduation in 1913 blithely skipped player piano plugging and instead advanced directly to New York City society. With wealthy family connections to sponsor him through a pampered apprenticeship of his own design away from the pop-tune sweatshops, still Porter had the instincts to give the public what they liked and at the same time urge them towards greater sophistication. And so he, elegant hedonist at heart, met his targeted audience with a decidedly worldly bent.

Porter pounded out a heap of unsalable melodies before he ever turned flush on annual royalties. His first known song, “Bobolink Waltz,” was dashed off in 1902 when he was in his ninth precocious year. “Esmerelda” hit the sales racks in l915, as reported above. Other numbers from Hitchy? “When I Had a Uniform On,” “Bring Back My Butterfly,” “My Cozy Little Corner in the Ritz” and “I’ve Got Somebody Waiting.” He himself had to keep waiting for the next nine years, toiling through a number of ill-fated ventures.

In 1928 at the Music Box, when he was 37 years old, Porter finally arrived with a musical called Paris, which was produced by Gilbert Miller and E. Ray Goetz, directed by W. H. Gilmore, with a book by Martin Brown. It contained one of Porter’s signature songs, the risqué “Let’s Do It,” so slyly in touch with the amorality of the era that audiences began to embrace the essential Cole Porter.

What other would-be tunesmiths destined for fame were still foundering in 1924 when Lady soared? Vincent Youmans could only deliver so-so trivialities to the Lollipop at the Knickerbocker theatre, while a still-struggling Richard Rodgers, like Cole Porter still far from a household name, worked with Larry Hart on the disappointing Melody Man, actually a play with songs (one being “I’d Like to Poison Ivy Because She Clings to Me”) and a drama so pedestrian that the two managed to keep their names off it. Rodgers had labored with his partner through a frustrating string of failures. They had suffered rejection from famed Max Dreyfus, who dismissed some tunes Rodgers played for him, including “Manhattan,” as “worthless.”9 You’d Be Surprised lasted all of one performance. Fly with Me stayed airborne for only four evenings. The composer, who in his impressionable youth had sat spellbound before a dozen or so performances of Jerome Kern’s Very Good Eddie hearing the kind of music he longed to compose, now nearly walked away from Broadway, so distraught was he over a career choice going nowhere. For a deadly spell, Rodgers considered abandoning the music business to become retailing specialist in kids’ underwear. Larry Hart, not quite so despondent, succeeded in etching out minor assignments applying his intricate baroque rhyming patterns to the melodies of other men.

Broadway would never be an easy place to conquer. Jerome Kern, the day’s reigning melody king, was now experiencing mostly frustration, too. In 1924, while the Gershwin brothers exulted in their new-found glory, Kern’s tepid Dear Sir was not politely answered by cheering ticket buyers. Nor was his more ambitious effort with P.G. Wodehouse, Sitting Pretty. Intended to resemble a Princes Street hit, it folded quietly without recapturing even a trace of his past glories associated with that theatre. Kern could only reminisce over the great days working at the Princess with tried and true collaborators Guy Bolton and Wodehouse and a jamboree of long-forgotten lyric writers.

Syncopated amusements were not an easy sell. The majority of ticket buyers flocked in even greater droves to the big successful operettas of the day. There was a reason: Not everybody found satisfaction in joke-filled revues strung together with flimsy story lines and salty player-piano tunes. The newer American shows routinely sacrificed plot development for a deference to song and dance. The typical operetta offered a durable libretto. And as easy as it is for critics of today to call them “silly” and “contrived,” in many ways they were not far removed from the serious book shows that would dominate the theatre fifty years later—just not so sophisticated, and certainly not as local. Old-world operetta composer Victor Herbert had referred to his 1908 work, Algeria, as “a musical play,”10 the same term used to describe a show that had opened eight years earlier, Martin and Martine. In the eyes of some, including author Ethan Mordden, Herbert was a bold innovator who sought “compositional unity,”11 in contrast to the prevailing practice of interpolating popular songs that bore no relevance to the plot or theme.

Vaudeville versus narrative integrity. Herbert’s Babes in Toyland had featured the villainous and miserly Uncle Barnaby, plotting to do away with his own niece and nephew in order to claim their inheritance. The Red Mill, another Herbert hit with book and lyrics by Henry Blossom, concerned a couple of tourists helping the young heroine secure her father’s approval to marry her true love. How silly is that? The public naturally responded to dramatic situations set to music. Franz Lehar’s Merry Widow, with a score rooted in traditional refrains, told the story of two ex-sweethearts eventually getting back together. Its universal appeal is evident in its touring schedule, which included cities in Africa, Asia and South America.

How much more substantial, really, is the story of a snobby English professor teaching a young cockney woman to speak proper English so she can impress a bunch of stiff necks (My Fair Lady) than is the tale of spouseless honeymooners discovering a superior match in one illicit embrace (Very Good Eddie)? It may reside in the execution. The operetta bore the imagery of substance and the semblance of storytelling. Some creators borrowed from epic historical tales, not unlike the work of Frenchmen Alain Boublil and Claude-Michel Schonberg sixty years hence. Rudolf Friml’s 1925 hit Vagabond King dramatized the adventures and romantic intrigues of François Villon, a 15th century poet rebel at the time of King Louis XI. Broodingly romantic, the operettas of Herbert and colleagues found steady patronage.

Through the 1920s, the American-bred shows of the newer composers could not rival these old-world workhorses at the box office. Lady Be Good, a hit that closed in less than a year, paled commercially next to a couple of big operetta favorites: Rudolf Friml and Herbert Stothart’s Rose Marie, which entertained almost twice as many patrons with a story about a singer who remains true to only one man despite the treacherous manipulations of a rival suitor; and the decade’s longest-running musical, Sigmund Romberg’s The Student Prince, a compelling melodrama about the bittersweet failure of the principals to rekindle an epic lost love. Both shows were marinated in an overabundance, by today’s standards, of long-winded love songs—perhaps best illustrated by Rose Marie’s contemplative “Indian Love Call.” Oscar Hammerstein, who co-wrote the book and lyrics with Otto Harbach, would remark many times over that what playgoers primarily responded to were engaging stories they could follow.

Or to snappy songs they could hum on their way out. The younger tunesmiths, who stuck with uptempo music despite lingering audience loyalties to the European-style fare, found their natural medium in the then-thriving revue format, elastic enough to host an evening full of miscellaneous songs. Revues lived in the present. They poked fun at changing mores, satirized known figures in society and politics. They addressed the jaded sentiments of New Yorkers. Writers took big, bold chances on untoward subjects. From The Charity Girl came a subversive little verse thumbing its nose at Indian love calls—”I’d Rather Be a Chippie [street walker] Than a Charity Bum.” In at least one city, police raided and closed down the charity girl.

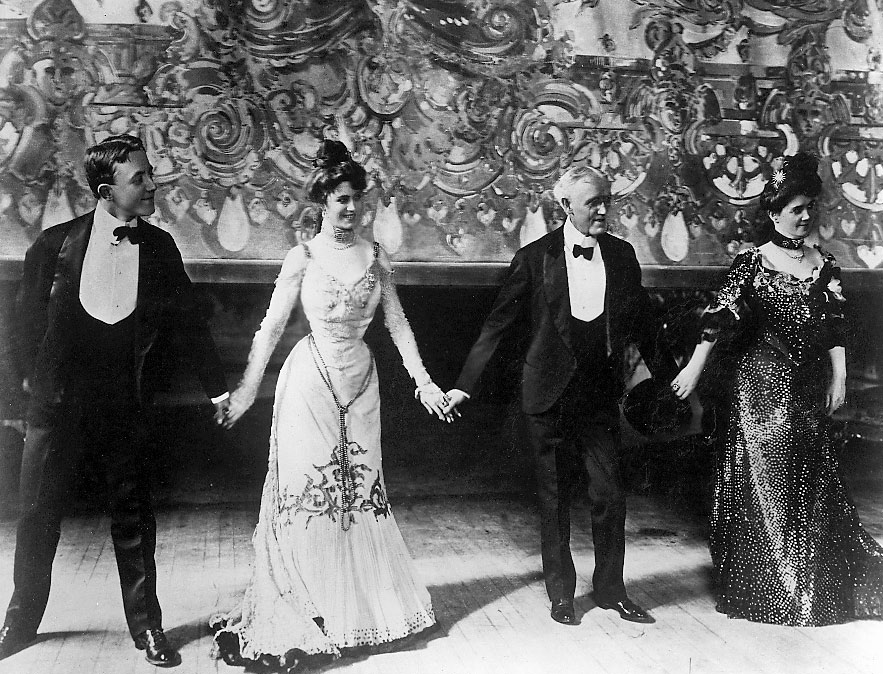

Left to right: Adele Astaire, Leslie Hensen, and Fred Astaire in the West End production of Funny Face.

Even some of the book shows courted a worldlier slant. Where to go for better source material? The Gershwin brothers certainly did not go anywhere far, not with Lady Be Good, nor with their 1926 sensation, Oh, Kay, which offered probably the most exciting score they would create together. It even contained a big ballad, “Someone to Watch Over Me,” which was not dropped. The songs in toto brim with effervescence—“Fidgety Feet,” “Clap Your Hands,” “Don’t Ask.” Get the album and fly with it. Every single number rouses the heart. And what, book-wise, was Oh, Kay up to? The writers Guy Bolton and P.G. Wodehouse had bootlegging on their minds. They thought up a trite little yarn about a titled English bootlegger in America stashing away some hooch in the cellar of a Long Island home, while his sister, posing as a cook to keep an eye on the hidden spirits, falls in love with the homeowner just when he is about to wed somebody else. The romantic outcome should not be difficult to guess. Everyone sings the scores praises. Few talk much about its libretto.

It is a perplexing truth, long in the realization, that the libretto for the American musical would prove more problematic than perfectible during the entire twentieth century. Not all the so-called “frivolous” story lines associated with these early day tuners are as bad or unworkable as the residual ill-will of critics and historians would have us believe. Some contained heady doses of wit and amusing characters. Most of them were arguably no worse than the extensively revised scripts that would supersede them in “revival” productions. “Silly” and “contrived” are not confined to a particular era.

“When We Get Our Divorce,” a song written by Hammerstein and Harbach for their and Jerome Kern’s 1926 hit Sunny, took a dashing step away from the operetta attitudes they had grown up serving. And yet, only one month later, Hammerstein was back on the stodgier side of the street with his next successful opus, the stiff and stuffy Desert Song, whose strong score, “stirring male chorus” and “abundant plot … floridly contrived” in Variety’s opinion offered the public “full value” for its money.12 Because he was by nature a playwright rather than a vaudevillian, because he longed to explore the human condition in greater depth, Hammerstein naturally gravitated to operetta. In fact, he would earnestly endeavor for the greater part of his life to link music and meaning more effectively. While younger composers of the day were chasing after Tin Pan Alley royalties, Hammerstein was lurching erratically towards a more advanced form of stage entertainment wherein libretto and songs were significantly integrated by virtue of absolute moment-to-moment relevance.

Came 1927. George and Ira Gershwin landed another big cake-walking charmer with Funny Face, a harmless little diversion about a young woman feuding with a guardian over a string of pearls belonging to her and having to engage her own boyfriend to steal them back. Less than a month later, however, a bold new American musical, with far more sobering issues on its mind, docked at the Ziegfeld Theatre. First nighters soon settled into their seats, silent and spellbound, toes rarely tapping, fingers rarely snapping. Losing themselves in the Mississippi River locale, they followed the story.