Stars in the night

Blazing their light

Can’t hold a candle

To your razzle-dazzle

—E. Y. Harburg

The New Haven Crowd—New Yorkers who would take the train up to Connecticut to see new musicals on their way to Broadway, jealously hoping to find turkeys-in-the-making to gloat over—must have found the 1940s an especially stressful decade, for during the war years most of the finest writers were at work. Innovation flourished. From fantasy to drama, from exotica to backwoods America, the decade produced a canon of musicals not before or since equaled. Call it the golden golden age.

At the forefront of excellence stood Richard Rodgers and his two successive collaborators, Lorenz Hart and Oscar Hammerstein II. First, Hart: Nearing the end of his troubled life, Hart found the inspiration to capture in musical theatre language the seedy world of night clubs and rented liaisons in a work of astonishing realism, Pal Joey. “Nothing was softened for the sake of making the characters more appealing,” wrote Richard Rodgers. “Joey was a heel at the beginning and he never reformed. At the end the young lovers did not embrace…in fact, they walked off in opposite directions.”1 This was the score that gave the world such gems as “I Could Write a Book,” “Zip,” “Den of Iniquity” and “Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered.”

And here was the project that totally absorbed the otherwise erratic Hart. He did not stand Rodgers up at any of the work sessions. Most of the songs were completed in three weeks. And what a formidable accomplishment it was, so consistently fine in every category. In “What Do I Care for a Dame?” Rodgers and Hart experimented with the extended soliloquy, a refreshing departure from the standard AABA song structure. The song segued excitingly into a ballet, with the music erupting into a jumbled cacophony of big city street noises during rush-hour—the sort of sound tapestry that Leonard Bernstein would employ years later in two musicals set in New York city.

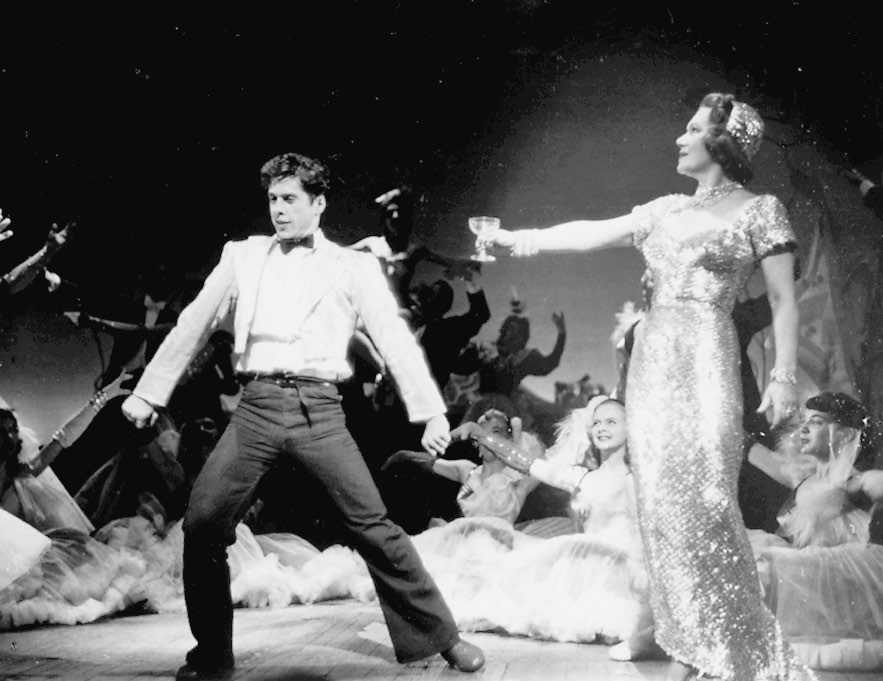

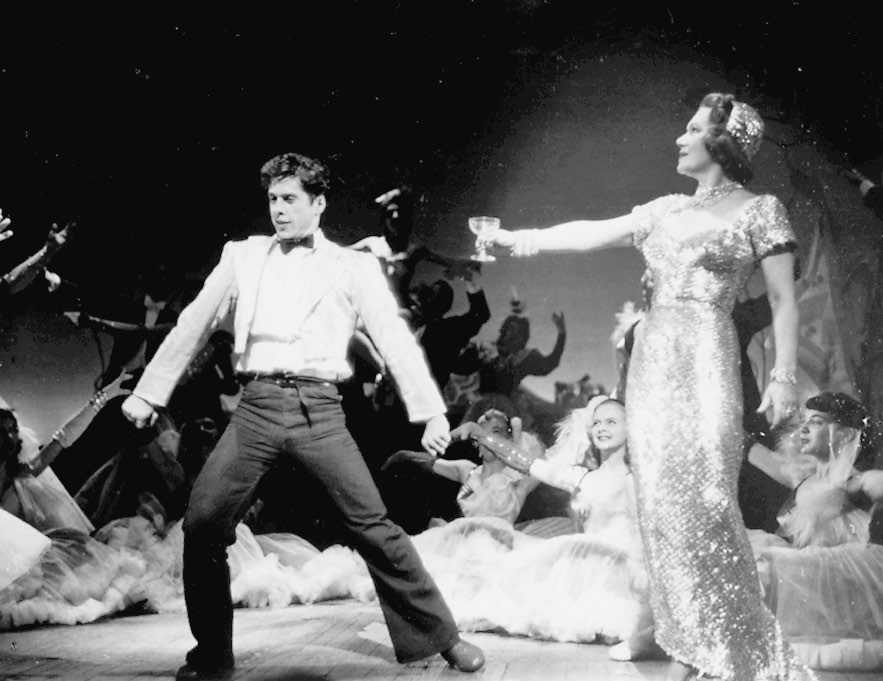

Harold Lang and Vivienne Segal in the 1951 revival of Pal Joey.

Pal Joey’s bleak anti-hero theme, judged by Abel Green of Variety “perhaps the major negative aspect to what otherwise is an otherwise amusing musical comedy,”2 did not find instant favor with everyone, even though a majority of critics endorsed it and it ran for 374 performances at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre. Cecil Wilson of the London Daily Mail found “a slyness and sophistication rarely encountered in a musical comedy.”3 Brooks Atkinson, who would later recant, is rumored to have caused Hart particular anguish by his terse dismissal: “Although Pal Joey is expertly done, can you draw sweet water from a foul well?”4 It would take ten more years of like-minded efforts to earn Joey the complete and widespread acclaim it deserved. Jule Styne brought it back to Broadway in 1952, where it handily topped its original run. Now, the reviews were unanimously favorable. “I am happy to report,” wrote Richard Watts, Jr., “that the famous musical comedy is every bit as brilliant, fresh, and delightful as it seemed when it set new standards for its field over ten years ago.” Now, others, at last, concurred. Now Brooks Atkinson saw the unsparing frankness of it all with belated praise: “It tells an integrated story with a knowing point of view…. Brimming over with good music and fast on its toes, Pal Joey renews confidence in the professionalism of the theatre.”5

Three seasons later came a new rural realism through the resurrected Oscar Hammerstein, who transformed his talent and fate by teaming up with Richard Rodgers to write the legendary Oklahoma! Just what drove the new collaborators to believe they could conquer the box office with the tale of a farm girl agonizing over competing invitations from two men for a box social may never be known. Was it sheer inspiration from the play by Lynn Riggs upon which it was based, Green Grow the Lilacs? When first presented by the prestigious Theatre Guild in 1931, that play ran a paltry 64 performances. Or was it the driving foresight of the Guild’s Theresa “Terry” Helburn, who, after attending the opening night performance of the 1940 revival of Lilacs, shared with cast members backstage a sudden desire to turn it into a musical? Or perhaps the burning determination of has-been Hammerstein to resurrect himself? With Richard Rodgers, whose current resume was far more impressive, Hammerstein approached the farmyard story with calm fidelity. Instead of raising the curtain on the usual stage full of dancing girls, the new collaborators arrived at “an extraordinary decision,” in the words of Hammerstein. “We agreed to start our story in the real and natural way in which it seemed to want to be told.”6 That meant the curtain would go up on the seated lone figure of old Aunt Eller, pumping away at a butter churn, while Curly, offstage at first, sang about a glorious haze rising over the meadow in “Oh, What a Beautiful Morning!”

On the wings of Hammerstein’s new-found poetry, the entire play soared. On the road to New York, where it first played under the title Away We Go, the show’s disregard for conventions—the oddly quiet opening scene, for example—tickled the New Haven crowd who, despite noticeable audience pleasure up in Connecticut, smugly reported back to their smart friends with smirking it’s-a-flop glee, “No girls, no gags, no good.”7 How wrong the cynics were. Oklahoma! established beyond resistance the template for the integrated musical. Overnight, Oscar Hammerstein’s lyric writing skills went from b+ to a+. The Riggs play gave him the kind of middle–America characters with whom he identified, realizing a kind of rural rapture in such perfect refrains as “The Surrey with the Fringe on the Top,” “People Will Say We’re in Love,” and “Out of My Dreams.”

And hounded, some said, by likely comparisons to Larry Hart, Hammerstein delivered humorous verse in such surprises as “I Can’t Say No” and “Poor Jud Is Dead,” the latter a tongue-in-cheek lament for a corpse fast fouling the air.

Virtually all the words came first, another drastic departure from the way such collaborations were usually run. Rodgers felt that working from this direction gave his music a more serious quality. What it gave Hammerstein was greater control over his own creative instincts, since he no longer answered to the set structure of already-composed music. Typically in the new R&H arrangement, a lyric that would take Hammerstein two or three weeks to write, once placed in typed form on Rodgers’ piano, would have a tune within minutes. Together they created a new standard of excellence for musical theatre, imbuing the form with two attributes that would characterize almost everything they did: craftsmanship and magic.

Only a few hours before the show’s New York opening at the St. James Theatre on March 31, 1943, Oscar took a walk with his wife Dorothy on a country road in Dolyestown. Haunted by the memory of the five previous musical shows upon which he had worked, all failures, he confessed, “I don’t know what to do if they don’t like this. I don’t know what to do because this is the only kind of a show I can write.”8

Oklahoma raised its inaugural curtain on a more hospitable era for Mr. Hammerstein. “Within ten minutes” of its opening, wrote Brooks Atkinson in his book Broadway, “a Broadway audience was transported out of the ugly realities of wartime into a warm, languorous, shining time and place where the only problems were simple and wholesome, and the people uncomplicated and joyous. The opening song seemed like a distillation of something that had been hovering in the air since life began on earth.”9

“It has, as a rough estimate, practically everything,” reported John Anderson. “Oklahoma really is different—beautifully different,” declared Burns Mantle. “With songs that Richard Rodgers has fitted to a collection of unusually atmospheric and intelligible lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II, Oklahoma seems to me the most thoroughly and attractively American musical comedy since Edna Ferber’s Show Boat.”

Still, Oklahoma did not completely escape the ill will of the New Haven crowd in at least one of the reviews, this one by Wilella Waldorf for the Post, who was not bowled over by its “old fashioned charm,” and went on to elaborate, “For a while last night, it all seemed just a trifle too cute…. A flock of Mr. Rodgers’s songs that are pleasant enough but still manage to sound quite a bit alike, are warbled in front of Laurey’s farmhouse, one after another, without much variety in presentation. It was all very picturesque in a studied fashion, reminding us that life on a farm is apt to become a little tiresome.”10

This “tiresome” picture was actually a triumph, whose old fashioned charm kept it on the boards for the unprecedented record of 2,248 shows. More importantly, Oklahoma signaled a tectonic shift in musical theatre plates; it pushed the integrated book show into maturity. Many people now viewed operetta as old hat, failing to credit its logical evolution into the book musical (unlike the Variety reviewer, who in a positive notice fittingly declared Oklahoma “further proof that the operetta form of musical show is still, and probably will continue to be, part of Broadway’s fare”).11 Even Brooks Atkinson displayed an irrational disdain for the earlier form whenever he crossed its path in a new work, walking out on the opening in 1948 of Sigmund Romberg’s roundly panned My Romance.

Oklahoma was anything but simplified operetta. Mr. Hammerstein presented two divergent worlds moving ahead on parallel tracks—the romantic one of Laurey and Curly, blessed by good looks and promising futures; the other, the barren existence of a clumsy loner and menacing misfit, Jud Fry, who can only dream of amorous embraces. Laurey agrees to attend a box social with Fry only because she has had a momentary tiff with Curly, whom she really loves. In the end, Fry’s anguish is multiplied by the realization of it all. In “Lonely Room,” Hammerstein paints a chilling portrait of Fry’s harrowing social isolation, trapped in a creaky old shack full of field mice scuttling about for crumbs, and feeling as inconsequential as a cobweb.

“The Farmer and the Cowman” in Oklahoma featured dancers Marc Platt and Rhoda Hoffman.

Jud Fry’s plight invests the show with a sobering realism which many still overlook; indeed, from Fry’s harrowing vantage point we see how precarious are the time-bound illusions of the young lovers. People might say they are in love, and they might be. They might also end up in their own lonely rooms. In a frightening sense, most of us live in personal fear of Jud Fry’s fate. In the end, the vengeful Fry crashes Curly and Laurey’s wedding, gets into a fight with his rival, and is accidentally killed with the knife he pulls on Curly.

Death stalks the most memorable Rodgers and Hammerstein shows, almost like a saving grace sparing each from terminal sweetness. In Carousel, their next work, Dick and Oscar pursued a similar social dichotomy, and once again they excelled with a love story between unequals. Julie Jordan succumbs to the crude charms of a carousel barker, Billy Bigelow, whose meager livelihood is supplemented by his gigolo association with the carousel owner. A triangle keeps the three in a tango between true and kept love. All the complex questions that arise over the ill-fated choice of mates form the fascinating bedrock of this masterwork, based on Ferenc Molnár’s play Liliom, which had originally been produced in Budapest in 1909, then by the Theatre Guild in 1921. Rodgers would call Carousel his personal favorite.

Hammerstein’s extended “Soliloquy,” a work of profound stature, charts the transformation of Bigelow from an out-of-work drifter growing restless in marriage, to a new man of conscience as he faces the prospects of fatherhood. At first Billy proudly anticipates raising a son. Then he wonders, in a state of shock, what he will do if the child is a girl.

So overwhelmed does Bigelow become with the contemplated responsibility, that he is murdered during an attempted robbery to raise money for his expected daughter. In the original play Billy returns to earth as a beggar, granted the brief visit by Providence for the purpose of performing a good deed. He only causes more mischief and harm—hardly the way to end a musical, in the opinion of Dick and Oscar. This lead them to interpolate the graduation scene, a device of their own making wherein Billy’s daughter, Louise, realizes self-worth through the inspiring “You’ll Never Walk Alone.”

Among the ringing endorsements Carousel received, possibly none was more perceptive or eloquent than that of John Chapman, who wrote, “One of the finest musical plays I have seen and I shall remember it always. It has everything the professional theatre can give it—and something besides: heart, integrity, an inner glow—I don’t know just what to call it…. Carousel is tender, rueful, almost tragic, and does not fit the pattern of musical comedy, operetta, opera bouffe, or even opera. Those looking for a happy and foolish evening had better go elsewhere…. The zip, the pace, the timing of the ordinary musical are not in it, but if offers stirring rewards for the listener who will adapt himself to the slower progression and let it tell and sing its story in its own way.”12

Other composers and lyric writers were inspired by the bold achievements of both Hart and Hammerstein to forge their own more deeply felt theatrical visions, and together they made the 1940s a particularly enchanting era.

German-born Kurt Weill put his political leanings on hold in the early forties to create a couple of commercially accessible pieces. First stop: the analyst’s couch. Weill tackled the jaded ambivalence of a wealthy neurotic who spends more time with her head shrink than she does with a trio of suitors among whom she is having a devil of a time choosing. The lyrics were by Ira Gershwin, the libretto by a real-life survivor of the couch, Moss Hart. Lady in the Dark, the result, managed to pull some effective theatre songs from Weill and Gershwin at a time when Freud was in vogue and when perhaps half of the audience was in psychoanalysis. The show’s then-fascinating premise kept it at the Alvin Theatre for a fine stay.

Another profitable collaboration for Mr. Weill was the light-hearted fantasy One Touch of Venus, about a statue of Venus coming alive when an admiring barber places a ring on its finger. Poet Ogden Nash wrote the lyrics and worked on the book with S. J. Perelman. It opened in 1943, six months after Oklahoma’s premiere, at the Imperial Theatre. In the cast was Mary Martin, making her first starring role in a Broadway show and introducing to the world, from a score rich in rueful sophistication and enchanting melody, one of the most haunting ballads ever written:

Speak low when you speak love

Our summer day withers away

Too soon, too soon

Speak low when you speak love

Our moment is swift

Like ships adrift

We’re swept apart too soonSpeak low, darling, speak low

Love is a spark

Lost in the dark

Too soon, too soon

I fear wherever I go

That tomorrow is near

Tomorrow is here

And always too soonTime is so old

And love so brief

Love is pure gold

And time a thiefWe’re late, darling, we’re late

The curtain descends

Everything ends

Too soon, too soon

I wait, darling, I wait

Will you speak low to me

Speak love to me

And soon

One Touch drew strong critical favor, with Variety’s Abel Green calling it a “musical smash,” its score “brilliant,” and predicting that “Speak Low” would become Weill’s “most durable ditty.”13 Louis Kronenberger, typically in step with his colleagues, wrote, “Whatever is wrong with it, One Touch of Venus is an unhackneyed and imaginative musical that spurns the easy formulas of Broadway, that has personality and wit and genuinely high moments of music and dancing.”14

During the war years, Americans preferred uplifting entertainment, and a number of New York–centered writers reached out beyond their normal milieu in an effort to connect with the population at large. While Irving Berlin had turned out a workable revue, This Is the Army, Cole Porter composed two second-drawer offerings of timely appeal based on the lives of ordinary soldiers and their spouses or girlfriends. The first was Let’s Face It, which gave Danny Kaye, its undisputed star, his first big starring role, and which he kept on the boards for 547 performances. The second was a schmaltzy Ethel Merman package without a hit song to its name, Something for the Boys, which at least proved that Mr. Porter might be able to function a few miles away from Gotham glitz and decay.

All rather pedestrian stuff, cheerfully executed by big name entertainers. Fortunately, there were younger writers with fresh ambitions who found ample drama and comedy in the plight of servicemen and the lives of those they touched. Leonard Bernstein, Adolph Green and Betty Comden launched their careers in musical theatre with a work of rare exuberance and sass, On the Town, the story of three sailors about to ship out and wishing for one last evening of romance, American style. Bernstein borrowed on themes from his symphonic work Fancy Free, weaving some into individual songs. Stand-up comics Comden and Green supplied taut attractive lyrics, by turns gutsy, sensitive and hilarious.

We’ve got one day here and not another minute

To see the famous sights!

We’ll find the romance and danger waiting in it

Beneath the Broadway lights

And we’ve hair on our chest

So what we like the best are the nights

Sights! Lights! Nights!New York, New York—a helluva town

The Bronx is up—and the Battery’s down

The people ride in a hole in the groun’

New York—New York—it’s a helluva town!Manhattan women are dressed in silk and satin

Or so the fellas say

There’s just one thing that’s important in Manhattan

When you have just one day

Gotta pick up a date

Maybe seven—

Or eight—

On your way—

In just one day.

“I Get Carried Away” was a laugh-fest. And if “New York, New York!” made the city seem like the most exciting place on the face of the earth, “A Lonely Town” turned it into a skyscraper canyon of haunting isolation. And in the end, when the sailors went off to war and their one-night girlfriends were left to ponder a night of temporary romance just ended, there was the painfully pensive “Some Other Time.”

Oh, what an inspiring war it was. And after it was over, the very talented and sensitive Harold Rome found the words to evoke the mixed emotions that people faced in its aftermath—after the boys came home and everyone had to adjust. Rome cast his Call Me Mister with many ex–G.I.s and U.S.O. entertainers. He wrote:

It’s a beautiful day, ain’t it?

So exciting and gay, ain’t it?

There’s a beautiful hue in the beautiful blue

CALL ME MISTER!Lovely weather we’ve got, ain’t it?

Not too cold or too hot, ain’t it?

There’s a beautiful breeze in the beautiful trees

CALL ME MISTER!There’s a lift in the air;

There’s a song ev’ry where;

There’s a tang in,

A bang in just living

Da-di-ah-da-daIt’s a beautiful time, ain’t it?

All the world is in rhyme, ain’t it?

It’s a beautiful shore

From New Jersey to Oregon

Just call me Mister

Be so kindly, call me Mister

Just CALL ME MISTER FROM NOW ON!

“Take It Away” was Latin all the way. “The Red Ball Express” referenced the forgotten plight of returning African-American servicemen. “Vitality and finesse are blended happily in Call Me Mister,” wrote Howard Barnes in the Herald Tribune. “This G.I. show about G.I. Joes is something of a boisterous romp as it takes satirical cognizance of military life, problems of reconversion, Park Avenue, the deep South, and even South American dances…. The Rome music and lyrics are as excellent as they are varied.”15

Other writers found their music in the new post-war euphoria and emerging prosperity. In the last of seven revues they wrote together, Arthur Schwartz and Howard Dietz celebrated down-home America, all of it outside the city limits of New York, New York, in their lively if limited Inside the U.S.A. Light satirical touches seasoned the upbeat festivities, one being a stop in Pittsburgh, site of industrial pollution being challenged by a choral society. The title song captures the innocent patriotism of those celebratory days—the rights of free and equal people to speak their minds, to worship freely and to join the political parties of their choices.

Another new team of Rodgers & Hammerstein–style romantics were Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe who after two flops finally took Broadway, with Brigadoon, the recipient of seven unqualified raves when it opened on March 13, 1947 at the Ziegfeld Theatre. Lerner and Loewe had helped raise the $150,000 needed to finance it by performing the score at fifty-eight backer’s auditions, the final one pitched during the show’s third day in rehearsal. Brigadoon took its patrons on a walk up a winding path into a world that has sadly all but vanished.

Can’t we two go walkin’ together,

Out beyond the valley of trees,

Out where there’s a hillside of heather

Curtseyin’ gently in the breeze?

That’s what I’d like to do:

See the heather—but with you.The mist of May is in the gloamin’,

And all the clouds are holding still.

So take my hand and let’s go roamin’

Through the heather on the hill.The mornin’ dew is blinkin’ yonder;

There’s lazy music in the rill;

And all I want to do is wander

Through the heather on the hill.There may be other days as rich and rare;

There may be other springs as full and fair;

But they won’t be the same—they’ll come and go;

For this I know:That when the mist is in the gloamin’,

And all the clouds are holdin’ still,

If you’re not there I won’t go roamin’

Through the heather on the hill,

The heather on the hill.

Less misty-eyed was Irving Berlin’s 1946 triumph Annie Get Your Gun. It was produced by none other than Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II, whose looming presence seems to have inspired Berlin to new heights. He created a set of songs amounting to almost one standard after another: “I Got the Sun in the Morning,” “Doin’ What Comes Natur’lly,” “The Girl That I Marry,” “They Say It’s Wonderful” “You Can’t Get a Man with a Gun,” “There’s No Business Like Show Business,” “I Got Lost in His Arms,” “Anything You Can Do” and “I’m an Indian, Too.” (Contrary to myth, however, only two—not nine—of the songs made it into Hit Parade territory: “Doin’ What Comes Natur’lly” and “They Say It’s Wonderful.”16) With a book expertly crafted by Dorothy and Herbert Fields, Annie Get Your Gun held court at the Imperial Theatre for over one thousand performances.

Left to right: George Keane, David Brooks, and William Hansen in Brigadoon.

When Mr. Berlin returned to the Imperial a few years later, hoping to duplicate his Annie Oakley success with a new show starring the Statue of Liberty, patriotic sentiment got the better of him and Miss Liberty proved only moderately diverting. It did contain the moving “Give Me Your Tired, Your Poor” and the exhilarating waltz “Let’s Take an Old Fashioned Walk.” But theatergoers in 1949 were not too moved by a contrived story about two rival newspapers caught up in a competitive search for the model who posed for the Statue of Liberty. Among a slate of wildly mixed notices from raves to pans, Richard Watts, Jr., wrote, “It is pleasant, good looking, tuneful, and surprisingly commonplace.”17 Miss Liberty generated one Tony Award, for a stage technician, Joe Lynn.

Unless they could make ’em laugh, could lift them with song and dance, they couldn’t much expect to move the audience with messages. When the war was over, Kurt Weill returned to his lecture podium and faltered, if nobly, through a series of morosely dramatic works. Street Scene, a 1947 entry, sounds all too similar in setting and tone to Porgy and Bess. A tale of ghettoland adultery replete with murder, it is honestly conveyed in songs very good but very depressing, with an added layer of suffocation supplied by the darkly brooding lyrics of American poet Langston Hughes. Surely the lyrics did not help Mr. Weill to compose any particularly memorable melodies for the average theatre patron. The show was doted on by critics (“his masterpiece,” exuded Brooks Atkinson;18 “Taut, tuneful and moving,” raved Variety), avoided by the public.19

One year later, Mr. Weill took on Alan Jay Lerner, and they moved ahead with the problematic Love Life, a vehicle both praised and scorned by the reviews. Several of its songs, available on vinyl, are consistently bad. Weill’s next offering, Lost in the Stars, with mediocre lyrics by Maxwell Anderson, proved to be yet another naggingly uneven venture that split the critics and attracted hardly a soul. Set in racially divided South Africa, as with so many of Weill’s works the heavy-handed polemics evidently left theatre patrons feeling more like parishioners facing a stern pastor. The “profitable box office success”20 projected by Variety amounted to 28 performances.

Ethel Merman plays Annie Oakley in Annie Get Your Gun.

Weill wasn’t the only artist sympathetic to social injustice. Another venture featuring the downtrodden was St. Louis Woman, a notable flop with excellent songs. Carousel director Rouben Mamoulian could not save the downbeat affair, the labor of co-writers Arna Bontemps and Countee Cullen adapting Bontemps’s novel, God Sends Sunday. Not at the Martin Beck Theatre, he didn’t, where St. Louis Woman drew generally unfavorable notices and lasted only a few months. “Too much drama and not enough laughs,”21 wrote a skeptical Variety critic. “The story is obvious and commonplace, with a certain folk-operatic flavor,” wrote Louis Kronenberger, “but without the proper operatic sell and excitement…. The show rations its fun very skimpily.”22 Served without rations, however, were the wonderful contributions of lyricist Johnny Mercer and composer Harold Arlen—illustrating once again how remarkably unsuccessful a great score can be when straddled to an abysmally uninviting libretto. Among the gems, there was this:

Free an’ easy—that’s my style

Howdy do me, watch me smile

Fare thee well me after while

’Cause I gotta roam

An’ any place I hang my hat is homeSweetnin’ water; cherry wine

Thank you kindly, suits me fine

Kansas City, Caroline

That’s my honey comb

’Cause any place I hang my hat is homeBirds roostin’ in the trees

Pick up an’ go

And the goin’ proves

That’s how it ought to be

I pick up, too

When the spirit moves meCross the river; round the bend

Howdy, stranger; so long, friend

There’s a voice in the lonesome win’

That keeps a whisperin’ roam

I’m goin’ where the welcome mat is

No matter where that is

Cause any place I hang my hat is home

Lena Horne withdrew during out-of-town tryouts, complaining openly to the press, “It sets the negro back one hundred years … is full of gamblers, no goods, etc., and I’ll never play a part like that.”23 Sorrowfully, Cullen, a promising Harlem poet, died two days before rehearsals began.

A decade of giants—some of them old pros finding fresh inspiration, others just breaking in. E. Y. Harburg, who grew up on the East Side next to the East River—“with all the derelicts, docks, lots of sailors and gangs”24—shared Kurt Weill’s compassion for society’s oppressed classes. Luckily for Harburg, he possessed a flair for crowd-pleasing satire and rhyme. With Harold Arlen, he crafted in 1944 Bloomer Girl, based on an unpublished play by Lilith and Dan James about the design of the hoop skirt by radical feminist Evelina Applegate at the time of the Civil War. The lovely atmospheric score produced by Arlen and Harburg—containing such delights as “The Eagle and Me,” “When the Boys Come Home,” and “Right As the Rain”—strangely did not reflect the show’s two most dramatic conflicts, the freeing of a family slave in the Deep South and the outbreak of the Civil War.

For the movies Harburg had written the classic “Brother Can You Spare a Dime” and had penned all the marvelous lyrics for The Wizard of Oz. So, following Bloomer Girl, back to Hollywood in the forties he traveled in search of more sunshine, palm trees and movie work. Instead, the proud life-long defender of progressive causes landed on the blacklist, a sobering experience that hastened his early return to New York City. Hollywood’s loss was Broadway’s gain. Harburg teamed up with Burton Lane in 1947 to create one of the finest scores ever, the heaven-sent Finian’s Rainbow. Harburg based the meandering libretto, which he wrote with Fred Saidy, on an idea of his own about a group of sharecroppers struggling to retain possession of their land and turning to a leprechaun for magical help.

One thing remains certain: The Lane and Harburg numbers—among them “How Are Things in Glocca Morra?” and “Look to the Rainbow”—overflow with wonder, wit and scrumptious melody.

I look at you and suddenly

Something in your eyes I see

Soon begins bewitching me

It’s that old devil moon

That you stole from the skies

It’s that old devil moon

In your eyesYou and your glance

Make this romance

Too hot to handle

Stars in the night

Blazing their light

Can’t hold a candle

To your razzle dazzleYou’ve got me flying high and wide

On a magic carpet ride

Full of butterflies inside

Wanna cry, wanna croon

Wanna laugh like a loon

It’s that old devil moon

In your eyesJust when I think I’m

Free as a dove

Old devil moon

Deep in your eyes

Blinds me with love.

Harburg’s singular genius for playful rhyming—technically an extension of a similar though less developed Ira Gershwin bent—took wry liberties with word spellings:

Ev’ry femme that flutters by me

Is a flame that must be fanned

When I can’t fondle the hand that I’m fond of

I fondle the hand at handMy heart’s in a pickle

It’s constantly fickle

And not too partickle, I fear

When I’m not near the girl I love

I love the girl I’m nearWhat if they’re tall or tender

What if they’re small or slender

Long as they’ve got that gender

I s’rrenderAlways I can’t refuse ’em

Always my feet pursues ’em

Long as they’ve got a “boo-som”

I woos ’em

“Excuse my rave review,” wrote Robert Garland, one of five enchanted first-night reviewers, “but—this is it. The brand new musical has everything a grand new musical should have…. Finian’s Rainbow is something about which to rave, an answer to a theatergoer’s prayers. It has the genius which is the result of the taking of infinite plans. The story has fact and fancy. The lyrics are racy and romantic. The music is melodious and modern. And the production—direction, scenery, costumes, choreography—is fresh and effective.”25

So many fine new shows drew inspiration directly from the war years or from their positive impact on American culture. Even jaded Cole Porter, who had spun most of his magic through an almost endless cycle of glib revues and silly book contrivances, surprised everyone by rising to the challenge of the new integrated book show when he composed the score for Kiss Me Kate, based on Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew. Silly and fun and theatrical, yes. Also a literate work of the newer musical theatre pattern that would enjoy numerous revivals in the years ahead. It has a very good script, and its songs are knockouts: “Another Opening,” “Why Can’t You Behave?” “Always True to You,” “Too Darn Hot,” “So in Love,” “Wunderbar.” The critics all fell glowingly in line. Stated Brooks Atkinson, “Occasionally by some baffling miracle, everything seems to drop gracefully into its appointed place in the composition of a song show, and that is the case here.”26

At a time late in the glorious forties when new songwriters were beginning to make their own marks—Frank Loesser with Where’s Charley?, Jule Styne and Leo Robin with Gentlemen Prefer Blondes—old pros Oscar Hammerstein and Dick Rodgers looked back over the war years as depicted in a best-selling novella from first-time author James Michener, and they delivered yet a third full-blooded masterpiece, South Pacific. It was their only show ever to earn a perfect set of raves. Never was musical theatre more down-to-earth or up in the clouds, more challenging or corny or exhilarating or political all at the same magnificent moment, than when Mary Martin, playing a young American nurse courted by an older Frenchman, sang exuberantly of her love for a wonderful guy.