Not since the music of Kern or Rodgers in better days gone by had a song so embraced the heart like a lover’s reassuring smile. “All I Ask of You,” that song, came late in the first act of The Phantom of the Opera, which opened at the Majestic Theatre on January 26, 1988, and was still playing there at the end of the century. Although the critics didn’t much like the show, although insiders smugly dismissed it with words like “manufactured,” “cold,” “derivative,” audiences felt differently. Carried to a sphere of high emotion that other musicals weren’t taking them to in those hapless nights on Broadway, surging crowds rediscovered the power of musical theatre to enchant and inspire. Thousands would return again and again to the same show to reexperience the magic.

Whence such freshly aggressive music, amounting to a bold reinvention of the show song? From Englishman Andrew Lloyd Webber, son of two music teachers, who grew up favoring the Beatles, rock and roll, Puccini, Prokofiev and one famous American tunesmith: “My idea, really, was Richard Rodgers,” Webber stated, “and then, subsequently, it grew into musicals in general by all the best writers and composers…. I supposed I was being influenced to compose my own tunes in roughly their style.”1 Two major sources in particular propelled Webber—one an obsession of his father’s, drilled into him at an early age, that “melody was the most important thing,” and the other, his devotion to Prokofiev. “I have an understanding of atonalism and dissonance—which frankly Prokofiev had, only I go farther than that. The other is that I have no fear about where I will make harmony go, so long as I can make melody take it there naturally.”2

Take it there, naturally or not, he did, and in a big way, essentially merging three sources of inspiration—Broadway, opera, and rock. Webber developed an expansive facility for dramatic scoring which he would express through a number of impressively diverse projects, from the crucifixion of Jesus Christ to a fading Hollywood star at the love-starved end of her and filmland’s golden era. Following his father’s admonition, Andrew mastered the all-important gift for melody, so necessary to great shows. At the same time, he would incur the lingering disdain of U.S. theatre practitioners and critics. No composer who sought respect in that incestuous little world, headquartered in Manhattan, was ever more dreaded or despised by his own peers.

Not so shocking, really, given the quirky history of critical irrelevance in the face of imposing new work. Stravinsky’s “The Rite of Spring,” which premiered in Paris in 1913 to audience-wide hostility bordering on revolt, springs to mind, as do a number of symphonic and operatic works originally panned by wage-earning know-it-alls. Never, in fact, are the experts more ill-equipped to earn their pay than when constricted by fetishes or hidden conflicts of interest from recognizing important new work.

Paying customers are sometimes the first to spot that something in the air. And in this story, it was the audience that spotted the genius of Andrew Lloyd Webber and elevated him to global renown. Take a look, once more, at the 1980s, this time with your focus on the work of Mr. Webber—and other foreigners, for that matter—that was not developed in the United States. You’ll hear the applause of younger, more diverse patronage, and you’ll see a few theatres bombarded with long lines of anxious customers that no amount of bad press could keep away. Were those ticket buyers conned into some grand illusion, itself artistically hollow at the core? Addicted to famed opera composer derivatives turned into elevator music? Those hits from the Brits, say what you will, kept a few houses on Times Square lit year after year after year, while quite a few others stood eerily dark.

As a lad, Andrew dreamed of spending his life in history and architecture, spirited by a natural fascination for ancient ruins and old medieval buildings. His mother, Jean, gave him his first piano lesson at the prep school he attended in London. His father, who trained as a plumber and who became the distinguished director of the London College of Music, once told Andrew that if he ever composed a song as good as “Some Enchanted Evening,” he’d let him know. “Well,” confessed Andrew many years later, “he never did tell me.”3

At Oxford, Andrew, then 17, met and was creatively smitten with Tim Rice, and he left school in order solely to pursue a collaboration with the older lyricist, all of three-and-a-half years his senior. “Andrew had this burning ambition to be Richard Rodgers,” recalled Rice, “while I sort of vaguely wanted to be Elvis.”4 Their first Rodgers & Presley venture, Come Back, Richard, Your Country Needs You, was not much needed by anybody in London, where it played a single performance, and, despite that, somehow got recorded on the RCA label.

Next, they created Jesus Christ Superstar, writing the songs in five and a half days, breathlessly atypical for the team, although not exactly for Andrew, who during those hurricane-paced days was furiously composing up a reservoir of melody from which he would draw for several shows to come. Rice shunned clever rhyming in deference to a more literal recitative approach, a bent not fancied by his future critics. Instead, he stressed narration over lyrical embroidery. The songs they crafted bristled with a youthful vitality which carried dramatic weight. Webber marshalled the force of electronic music to build an unforgettably intense climax in the crucifixion scene, where a rock-fashioned crescendo nearly blows the rafters to smithereens. The two boys flirted with links between the ancient story and the modern pop world. Mary Magdalene’s “I Don’t Know How to Love Him” conveyed the mystical uncertainty of the unrequited lover, while the show’s title song bore a brazen new voice never before heard on the stage, a kind of acid rock fanfare—or, if you like, an overblown riff turned up to the highest decibels.

Not so curious, at all, that Rice and Webber should have entered the theatre this way, given their religious backgrounds. Rice harbored a boyhood fascination with biblical stories, and Webber, raised somewhat dispassionately in the Catholic church, would in later years return to the roots of his faith when he composed the eloquent Christmas-oriented “Requiem.” In fact, there are distinctive threads of church music that weave through Andrew Lloyd Webber refrains, investing them with a subtle spiritual dimension, though he seems either unaware of the fact or unwilling to acknowledge it.

Webber’s Superstar melodies revealed a bold new innovator in show music. He and Rice, a perfect fit for the long-haired sixties youth culture, took the stage with audacity once they actually got there. Unable to interest a producer at first, instead of holding backers auditions the American way they raised the money to record their songs in album format. And this led to Robert Stigwood, who had produced Hair in London, picking up the property and premiering it on the West End, where it became the longest running British musical of its time. Still, the show was easily snubbed as a fluke of clever promotion—a rock album blown up into a headline-grabbing extravaganza. In the U.S., where the scribes split wildly in their opinions, Jesus Christ Superstar did not duplicate its phenomenal West End success, even though it pulled off a profitable 711-performance run. And it ran up against a backlash of conservative voices, appalled by the crass exploitation of so sacred a story. Billy Graham denounced it.

In the secular word, Walter Kerr lined up in favor of the work itself, but not of the rather overheated Tom O’Horgan–conceived production that introduced it to Americans: “O’Horgan has adorned it. Oh, my God, how he has adorned it….” Douglas Watt found it “so stunningly effective a theatrical experience that I am still finding it difficult to compose my thoughts about it … It is, in short, a triumph.”5

In 1976, Webber and Rice revamped and expanded an earlier effort, another Bible adaptation called Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat. Its wonderful songs drew on early Beatles romanticism. Originally done in 1968 in a fifteen-minute version as a children’s oratorio, Joseph was lengthened to forty minutes in 1973, then by another quarter of an hour for a West End debut three years later. From there it was shipped across the sea and presented at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in 1976. Then to Broadway, five years later, where it received notices both very good and very bad. Christopher Sharp scolded it for being—horror of horrors!—“essentially children’s theatre.”6 Its tunes are entrancing, its lyrics hip. Its New York run lasted an impressive 824 performances. National touring companies—with whom singer Donnie Osmond has been a headliner—now and then continue to draw appreciative family audiences.

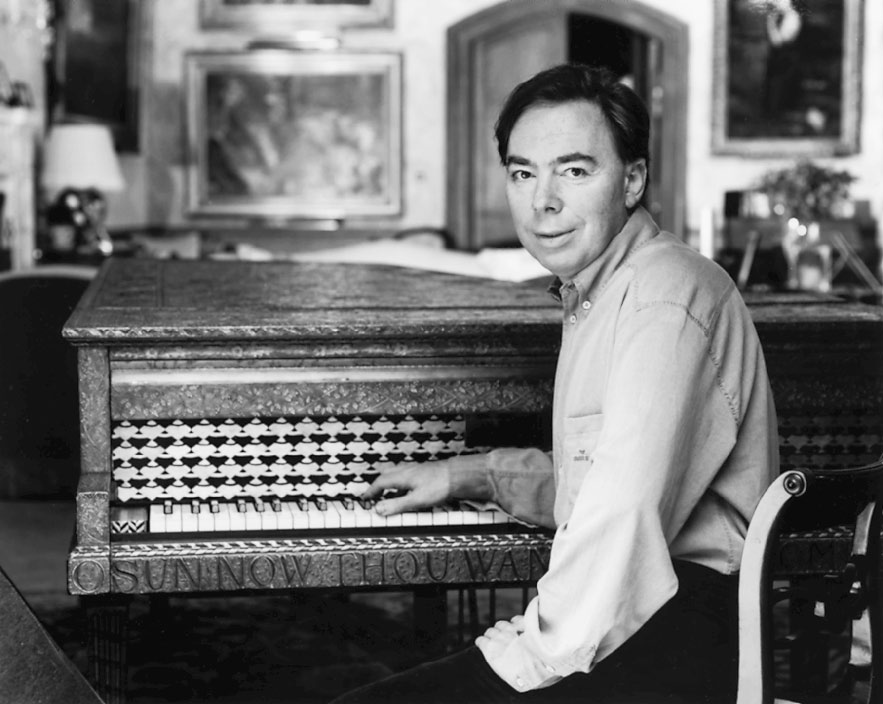

Andrew Lloyd Webber.

Rice and Webber returned to New York, in 1979, as daringly as when they first called, now with a musical about Argentina’s Eva Peron, a woman of beauty and ambition who slept her way up the political back-bedroom ladder to become ruler of the nation. Evita’s music was steeped in torrid latin rhythms, and, like Superstar, sung-through. This Webber-Rice opera derivative would have profound long-term effect on how musical theatre came to be created and sold to the public, especially to younger crowds and opera fans. Without dialogue getting in the way, all the picky literalists who squirmed in their seats over the sight of a character “breaking into a song” were spared the ordeal.

The Rice and Webber treatment of Ms. Peron’s story is a blistery tour-de-force not welcomed by a lot of folks who happen to like characters “breaking into a song,” who happen to insist on likable protagonists to root for and believe in. Evita shrewdly succeeded despite its coldness where most other musicals of a similar psyche fail. Why? Here was a compelling take on one of life’s most sobering realities: Some of the most effective and revered political leaders are themselves amorally ruthless. Evita conveyed this vexing irony with brute theatrical force. It was, to be clear, refreshingly unlike so many crippled shows that stagger into New York City, having been nursed over by hordes of script doctors and vacillating producers desperately settling for bubble gum because all else on the road seemed not to be jelling, and still in search of a purpose. Evita knew, minute by minute, exactly what it was about. Harold Prince’s brilliant uncompromising direction helped underline that clarity.

“Don’t Cry for Me, Argentina” sings like an authentic national anthem that has existed for years. By accident, not until minutes before it was about to be recorded during the final pre-production studio session for an album of the songs did Tim Rice come up with the title line—a spur-of-the-moment idea to replace the original words, “It’s only your lover returning.” The song was revved up to ’70s dance-club tempo, and it became an international disco hit eighteen months before the show ever opened, which helped jump start the box office. Other songs, too, were danceable: “Buenos Aires” was built on the cha-cha, while “On This Night of a Thousand Stars” drifts sensually on the slow rise of a carioca beat. Together, the hypnotic, story-advancing songs comprise Webber’s most unified work, validly dramatic at every turn.

The 1978 opening left West End critics gasping for superlatives. The British may be a more realistic lot. A year later, the musical came to America and got some kind of a cold shoulder. Variety saw 6 pans and 2 inconclusive notices; not so More Broadway Opening Nights, which pulled one rave out of the pile, one mixed, one unfavorable and only two pans. Let Clive Barnes speak for the fractured reactions: “Evita is a stunning, exhilarating theatrical experience, especially if you don’t think about it much. I have rarely ever seen a more excitingly staged Broadway musical…. The fault of the whole construction is that it is hollow. We are expected to deplore Evita’s morals but adore her circuses.”7

Andrew Lloyd Webber was by now the more ambitious of the pair. Webber set up his annual Sydmonton Festivals, conducted on his own property, to try out work-in-progress on a circle of trusted friends and associates, invited to offer critical feedback. All had to swear not to share the goings-on with outsiders. And by now, Rice and Webber were increasingly at odds with each other’s differing attitudes about work and play. Webber composed relentlessly. “A perfectionist,” said his biographer, Gerald McKnight, “he worked long, exhausting hours shaping and selecting melodic frameworks and orchestrations for his compositions. The excitement for him lay in using fresh, original sounds.”8 Rice resisted taking part in time-consuming sessions around a piano. He deemed vacation time, friends and travel as equally essential to his well being. Once he tried his hand at being a disk jockey. Another time he took a holiday to Japan, where he had spent a year of his boyhood attending religious schools while his dad worked in the country.

Before they wrote Evita, Rice had declined to become involved with Webber on By Jeeves, which Webber ended up writing with Alan Ayckbourn. After Evita, when Webber turned to the poetry of T.S. Eliot for the stimulus to compose his first mega hit, Cats, he approached Rice about working on one of the songs, “Memory,” which needed additional words to supplement some Eliot lines. Rice again declined to tango—not just once, but twice. Recounting this impasse, in itself a precarious act of memory, calls to mind how suddenly motivated certain individuals will become through perceived rivalries. After alternative lyricist Don Black supplied a set of words for “Memory,” not judged suitable, and after director Trevor Nunn came up with words which Webber loved—well, then, here came Rice with a cat-like change of heart. He spent three whole draining days on his own lyric for “Memory.” Too late, Tim. Trevor’s entry was quite wonderful, and since Trevor was given ultimate authority to select which one to use, Trevor chose Trevor. Mr. Rice felt royally rejected, and he aired his bitter hurts with the press. “I was extremely annoyed,” he told a Guardian reporter.9

Without Rice, Webber continued his reinvention of the musical into epic pop opera pitch, making it in subtle and not-so-subtle ways something distinctly different from the American musical play which had blossomed through the 1950s. Wisely, too, Webber moved quickly away from rock into a more eclectic arena—into the amplified fusion of popular music with quasi-classical idioms. This had the effect, horrifying to some, of coarsening the entire enterprise into a spectacle of manipulated sound. Though the music emanated from a single soul, the electronic glitter and all the garish arrangements gave it a kind of ponderous grandeur. Webber’s devout critics may be actually bothered more by the technical enhancements and the bravura performances than by the actual songs themselves. Nonetheless, millions of theatergoers around the world heard real music and were moved.

Cats is many things to many people—fantasy, revue, allegory, even fledgling book show struggling for breath under the hulk of a monster junkyard set so real, it’s a legal wonder no theatre where Cats played was ever shut down for safety code violations. At its purry core, Cats is an ingenious musicalization of Eliot’s trenchant verse about the imagined ways of various felines. The freshly wrought tunes, full of gaiety and pathos, are an honorable match. Charm and fantasy much compensate for a rambling music hall format, starring Grizabella, the aging glamour cat whom some reviewers have taken to be an over-the-bed prostitute waxing lyrical over better, more admired days. Between the slumping sections that feel padded, there are unforgettable moments, like “Jellicle Ball,” about as mystically enchanting as anything the stage can offer.

The exalting “Memory” saved the show from premature oblivion in a real junkyard. Producer Cameron Mackintosh was ready to close down his pet shop when—like a little lost kitten finding unexpected favor in the lap of an admiring stranger—“Memory” swiftly catapulted into hit status on Brit radio stations. Cats became a box office darling. At century’s end, it was still charming Broadway audiences at the Winter Garden, where it had opened on October 7, 1982.

In 1985, Webber took on writer Don Black, whose “Memory” lyric he had also rejected, and they took a worldly look at the sad little heartbreaks of expedient relationships in big city environs. They titled their gem Tell Me on a Sunday, and it was presented as the first of a two-part evening, Song and Dance. Skipping over the dance half (Webber’s arranged variations on Puccini’s “A Minor Caprice,” a wow in itself that deserves more appropriate discussion in the pages of dance tomes), Tell Me packs a well-honed wallop. Black’s lyrics are high grade, fresh, insightful, witty—piercingly to the point. Webber’s music is just as fresh and sharply contemporary, following trails forged by artists from Helen Reddy to Donna Summers.

This being a one-woman show, the songs are all sung by the heroine of the piece, a young British woman who goes to New York, via Los Angles, in the fragile hope of finding a glamorous life complete with Mr. Right. She finds it fleetingly through dalliances with four men, and her sweet resignation in the end to a fruitless journey is ingratiating and not a little noble. “Capped Teeth and Caesar Salad,” “You Made Me Think You Were in Love, “The Last Man in My Life,” and “I’m Very You, You’re Very Me” are a few of the score’s captivating treasures, tracing the heroine’s funny-sad romantic adventures and letdowns. Tell Me on a Sunday unfolds with taut efficiency.

The original treat, another Cameron Mackintosh–backed show, lasted for only 474 performances, a niggardly run by Webber standards. Unlike the maestro’s other hits, Sunday was not a spectacle, nor was its heroine a bigger than life character from extraordinary circumstances. She was a real person in the present tense. And when it came to composing songs for real people in the unexotic here and now, Mr. Webber seemed afflicted by a strange handicap. Give him something fantastic, like, say, an old steam engine racing against a cold-hearted electrified locomotive for champion of the tracks, or a theatre phantom possessed of a chorus girl, and then the Andrew Lloyd Webber box office opens extra windows. And the theatre gets rented forever, making the Nederlanders or the Shuberts, landlords formerly known as producers, very happy.

About the little puffer with a heart of steam, it chugged like an aging star on the comeback trail through Starlight Express, another show high on cinematic stagecraft, topped out by dazzling laser-beam effects. Webber’s pop score, with lyrics from several hands lead by Richard Stilgoe, is one energizing amalgam of rock, soul, funk and pop, all cleverly in tune with the action, and all rendered in funky good taste. Every cast member appeared on roller skates for the entire shindig, swooping out at times over the orchestra seats on special stage-level ramps. They rolled across the Gershwin Theatre a respectable 761 times before New Yorkers would no longer tolerate the roller derby of novo musicals from Great Britain. In less snooty places like Las Vegas and London, they were still whizzing across the ramps at century’s end.

Then came Webber’s triumph, The Phantom of the Opera. He and this gothic tale were made for each other, and in his passionate adaptation, assisted by Richard Stilgoe, Webber matured by dazzling degrees. The story itself holds strong fascination; there is probably a phantom of the opera in all of us—that part of our lovesick soul that has ached for someone we will never have. The disembodied voice of this phantom stalks the Paris Opera House, bellowing forth his capricious demands to its new proprietors: Do what I say! Make Christine the star! Retire your aging prima donna! Replace her with Christie, or suffer the wrath of my certain revenge! And by measures ever more ominous as the threat builds, the theatre lights go out, performances are shuttered, a chandelier comes tumbling (kind of) down over the audience and, finally, a hangman’s rope drops around the neck of Christine’s rival suitor, Raoul.

Even then—there is at least one other stage version out there, by Maury Yeston, with limited box office appeal that some critics prefer—it is hard to imagine Webber’s Phantom enjoying such long-lasting patronage around the world without the soaring melodies which he created for the fine lyrics supplied by Charles Hart, supplemented by additional verse from Richard Stilgoe. The power of music turned this bizarre tale into a heart-pounding experience. “Think of Me” invites us into the strange sadness of the heroine. The “Phantom” theme assaults us with the masked antagonist’s deranged infatuation with Christine. “Prima Donna” lavishes false praise, ever so flamboyantly, on a fading star about to be replaced by the Phantom’s favorite singer. “All I Ask of You” plays to our deepest romantic longings. “Masquerade” raises a shrill salute to the costumed hypocrisies behind which we so sheepishly hide, and to the fleeting nature of the physical beauty we so foolishly pursue. “Wishing You Were Somehow Here Again” overflows with hopeless nostalgia. “The Point of No Return,” a dark tango, hovers erotically on the brink of forced seduction. Webber’s charts play out almost like a symphony, the variously shaded refrains mirroring the Phantom’s demented agenda as it impacts the lives of all who inhabit the Paris Opera House. When, at the last moment, the Phantom feels inevitably driven to remove his mask, thus exposing the deformed side of his face before a crestfallen Christine, he in effect presses us all up against the tragedy of his doomed desire, and the empathetic moment affects a powerful catharsis.

Detractors claim that The Phantom of the Opera is no more than a cunning theatrical contrivance; escaping them, somehow, is the heart-wrenching story of unrequited love it tells, and with such potent words and music. Among the complaints, we are told it has “no conflict,” the music “sounds all the same,” the story “repeats a one-theme obsession ad nauseam,” the falling chandelier “is what really pulls the audiences in,” and without the spectacular stage effects “there would be no show.” Some of these same complainers report quality sleep during the one obligatory visit they made to see Phantom.10

Many of them anxiously await the long-planned, regularly delayed revival, in revised form, of Cole Porter’s Out of This World. Some claim that Kurt Weill never got a fair shake; others, that some obscure musical produced in the early ’80s marks the last decent act of musical theatre in the twentieth century. While arguing the demise of a great American art form, they fail to acknowledge that musical theatre has traveled a circle amidst shifting influences—from the early days of the century when shows from abroad dominated the New York theatre scene, through decades of home-grown success, to a time, one hundred years later, when European influences again hold sway.

Alan Jay Lerner, one of the few remaining pros from the golden age to hear some of Webber’s early work, spotted a major new voice in the air: “Webber’s childhood was steeped in the classics, which becomes more and more apparent the more one listens to his music. Influences abound, but they are filtered through a very distinctive musical personality, which gives his music a sound of its own.”11 Lerner lived long enough to attend a performance of Cats, whose score he found “remarkably theatrical.”12 Near the end of his book, Musical Theatre: A Celebration, he opined that, compared to “one-of-a-kind” Sondheim, who “cannot be imitated except by cloning… Webber, on the other hand, speaks in the popular musical language of the day, more literate but, nevertheless, contemporary through and through; and form, in these particular times, is apt to cast a longer shadow than content.”13

Just as the music of Jerome Kern has endured for nearly ten decades, so, too, will the finest melodies from Cats and Evita and Joseph and Phantom live on. And there will no doubt come a day, many years hence, when fans of the Broadway musical will ruefully reminisce over the time when Andrew Lloyd Webber ruled the commercial stage. Having discovered in his absence a new-found appreciation, they will sing his songs in their staged concert readings and regional revivals. They will wonder why they ever denigrated his contributions in the first place. Now, at last, they will speak of songs like “Think of Me” with the same affection and respect reserved for Kern and Rodgers, for Gershwin and Porter.

All the negative reviews in the world cannot kill a good tune—or show—once the public gets a hold of it.