Cats. The Phantom of the Opera. Les Misérables. Miss Saigon. Four mega hits from the Brits, all introduced to America through the early 1990s, were still on Broadway at the end of the century. Following the premiere of Miss Saigon on April 11, 1991, however, for the next ten years nothing new from Britain turned a profit in a New York House. This said as much about the fleeting nature of creativity as it did about the variable fortunes of producers—in this case, about Cameron Mackintosh, the young impresario who had a hand in all four imported triumphs. Had the West End wizard of record-shattering productions lost his magic touch?

Like his countryman Andrew Lloyd Webber (with whom he shares the birth year 1948), Mackintosh hummed American show tunes in his youth. Just short of his eighth birthday, he got “dragged” off to see the English musical Salad Days. “People singing and dancing seemed sissie to me, but of course I was captivated.” He returned on his birthday, and, after the performance, marched down the aisle to introduce himself to the composer, Julian Slade, who played the pit piano. Slade escorted eight-year-old Cameron backstage, a career-defining moment. “I saw how scenery came in and out,” he told Barbara Isenberg of the Los Angeles Times, “and I wanted to put things like that together.”1

Did he ever. By age 19, Mackintosh, who regarded My Fair Lady as the greatest musical ever written, got a job in London as assistant stage manager for Hello, Dolly. By his late thirties, he conquered the stage with a savvy for marketing musicals worldwide not before or since equaled. Flushed with global conquests, Mackintosh became the most successful theatrical producer ever, hyping shows into international household names.

At the summit of his producing fortunes in the late ’80s, Mackintosh liked pointing out how most every new musical he saw (or was pitched, via demo tape) could have been composed during the last forty years. Too staid, too old fashioned, he implied, unlike the more contemporary work he believed he was producing. (His smug assertions did not always hold, for strewn among the Mackintosh-sponsored scores under scrutiny herein are tunes that sound like they could have been written forty years ago.) Mackintosh pushed his image as visionary presenter of new work. New or not, it was packaged in spectacular state-of-the-art fashion. The producer immersed his audiences in orgiastic displays of modern stagecraft technology, some of it so complex as to outdo special effects in today’s movies.

In skeptical reaction to the pyrotechnics involved, critics of the Mackintosh touch argued that they drag down the art of musical theatre to a lower level of crowd-pandering spectacle, and that audiences, promised fireworks, are hauled in for the wrong reasons. It’s a dubious charge, for without the critical goods—the stories, the characters and the songs—none of the shows could have prospered so. And if Mackintosh is guilty of extreme showmanship, he is hardly the first impresario to have bolstered his commercial prospects by investing in lavish productions. The Wizard of Oz, with a book and lyrics by L. Frank Baum himself, was in 1903 the premiere event at the new Majestic Theatre, and contained “brilliant scenic effects,” beginning with a cyclone on stage, as reported by the New York Times. “It cannot be said,” remarked the anonymous reviewer, “that the authors have shown any great originality, but they have thrown old and well approved materials into a pleasing shape.”2 Florenz Ziegfeld did much the same years later when he threw girls, glitter, and scenery into his opulent revues.

If Peter Pan can fly across the apron, why can’t a chandelier fall or a helicopter land? The theatre, a rather schizophrenic place caught between make believe and in-the-flesh immediacy, has by tradition called on leading engineers and artists to help make its illusions more believable. At the same time, it continually struggles with its more theatrical urges—born out of vaudeville, blown up in musical theatre, egged on by the intimacy shared by audience and actor—to break free of naturalism and simply strut. And simply mug. And simply resort to another amusing aside. And simply cakewalk and charm us for the hell of it.

And therein lies a delightful dichotomy. After all, each night ushers in a different performance. If we don’t exactly look for the strut, well … when it pops up, cane in hand, hat cocked across glinting smile, we can hardly resist the encouragement it seeks. And we laugh and applaud. It can show up anywhere at anytime, smack dab in the middle of something otherwise serious, as it does in the second act of Mackintosh’s Miss Saigon, in a bulldozer of a razzle-dazzlement called “The American Dream,” a number tenuously irrelevant yet oh-so irresistible. It cares only about pleasing a crowd of people, about showing off and stealing unexpected attention, so nakedly single-minded is it, daring us to deny ourselves the pleasure of its audacious company.

Let’s be adult about this. Broadway musicals at heart are like children of irresistible charm who simply refuse to grow up, refuse to behave along rational lines. They leap at us across the footlights with grimacing faces and wiggling outstretched arms, with fingers snapping up a breeze of infectious goodwill. They’re forever competing to keep everyone laughingly on their side, in their camp, no matter how insignificant their reason for being there. George Abbott, not a Pirandello or a Beckett, knew this. He loaded the stage with juvenile merriment, with zany crossovers and far-fetched chases. If it worked, if it moved the show along, in it stayed.

A producer like Cameron Mackintosh has history on his side when he orders realistic sets and yet shamelessly allows party crashers into the proceedings: songs barely related to the story that might make the hit parade just in case the show has nothing as good to offer or its fireworks backfire; popular personalities known for dispensing charm in a void, as insurance against flat dialogue or saggy direction. History on his side: Senior vaudevillian Danny Kaye did major compensatory work in a Richard Rodgers late-career bust, Two by Two. That stolid old hack work based on the Noah’s ark story drew almost every sort of critical reaction known to the theatre. When Kaye broke a leg, did the show fail to go on while he recovered? Of course not. The show went on with crutches. And what a hoot it was. Rodgers, however, did not laugh, recounting how Kaye, a “one-by-one vaudeville act,” would goose the chorus girls with crutches or purposely run into others, slapstick style, or make up his own lines as the spirit moved him and sing his numbers in unusual tempos. At selected curtain calls, Kaye addressed his adoring fans, “I’m glad you’re here, but I’m glad the authors aren’t!”3 By that time, in fact, insiders guessed that without Kaye’s outrageous antics, Two by Two might not have drawn the crowds it did. The 343 performance run made a few pennies.

Another professional cut-up, Carol Burnett, was credited for turning the ho-hum Once Upon a Mattress into a hit. Sobering to contemplate how many not-so-good-musicals, originally dismissed by the Fourth Estate, prove better than initially thought when, through different casting or fresh direction in revival format, they engage as never before. ’Twas always thus: In 1927, the Gershwin brothers struck out on the road with Strike Up the Band, an austere anti-war tuner with a book by George S. Kaufman. Three years later, Morrie Ryskind rewrote the libretto, safely reducing it to a silly satire about a war between the U.S. and Switzerland over tariffs for imported cheese. The salvage operation pulled in the old-time comedy team of Bobby Clark and Paul McCullough, who made a big amusing difference. The smaller pit orchestra, lead by Red Nichols, included a stunning array of then-unknowns: Benny Goodman, Gene Krupa, Glenn Miller, Jimmy Dorsey and Jack Teagarden! Strike up the band they did, to a revamped George Gershwin score remarkably influenced more by Kern than by Gershwin. The reconfigured version turned a tidy profit during a 191 performance run at the Times Square Theatre, thanks not exactly to the craft of drama.

Cameron Mackintosh likely learned early the critical importance of “production values” and trained himself to survive accordingly. The “living theatre” is forever vulnerable to the quality and the vision of each individual staging. Producers can’t always pick their stars—but they can pick the scenery and the chandeliers. Some go amusingly overboard in desperation to build critic-proof hits. More drops. Bigger turntables. Glitzier this or louder that. By the time Andrew Lloyd Webber’s epic feline fantasy Cats purred into New York city, the scenery itself represented a new plateau in set decoration. Not only did it transform the stage of the Winter Garden into a bigger-than-life junkyard, its beguiling surrealism spread vividly across the proscenium, inviting patrons to break through the fourth wall and take up residence with Grizabella and her motley crowd. Mackintosh and Webber likely concluded that all that gargantuan set construction had something to do with the show’s great success around the world. Well may it have. What followed from the pair kept the stage crews working overtime and the wings loaded with computers.

Cats: Maria Jo Ralabate is “Rumpleteazer” and Roger Kachel is “Mungojerrie.”

In the middle of it all stood Mr. Webber—not only the composer, but the co-producer. And so he was viewed by the New York provincials as a co-conspirator with Mr. Mackintosh in an insidious drive to transform Times Square into a theme park of overproduced thrill tuners. Webber was tagged a hack whose real genius lay in self promotion and the shrewd selection of directors who could convert his hamburger into filet mignon. Worst of all, he was a musical plagiarist. Guilty as charged? If so, at least he had the good taste to lift from the right sources. In the words of his brother, Julian, “Andrew will never take from anyone whom he does not respect, I can assure you.”4

Soon enough, a well-followed hate-hate relationship between Mr. Webber and the press turned into a sideshow of competing put-downs between critics on both sides of the Atlantic. Those songs by Andrew, carped his enemies, were floridly sung and amplified, and they all sounded alike. Between Webber’s refrains and Mackintosh’s scenery, the scribes had a field day’s worth of targets to shoot at. Their irritable notices became ever more entertaining. Walter Kerr—one of a trio of writers, you may recall, responsible for a progressive highlight of the ’50s, Goldilocks—spent many a Sunday column in his capacity as drama critic for the New York Times articulating major reservations with Webber’s work, while Frank Rich, the Times’ daily reviewer, took care to reiterate at every turn his impatience with Webber. They disagreed on Cats. Kerr quipped, “You will get all the colorful extravaganzas I’ve mentioned, and more. You will also get tired.”5 Rich conceded, “It believes in purely theatrical magic, and on that faith it unquestionably delivers.”6

Then came Starlight Express, which drove to exhaustion Mr. Rich, who termed it “the perfect gift for the kid who has everything except parents.”7 And then Phantom, whose songs he grudgingly succumbed to, reflecting, “…as always, they are recycled endlessly. If you don’t leave the theatre humming the songs you’ve got a hearing disability.”8

Meanwhile, back on the Times’ Sunday food and theatre beat, Mr. Kerr likened Phantom’s musical reprises to “steady drip molasses,” the soft landing of the chandelier to a free-falling tart of sorts: “It sways a bit … looking for all the world like the biggest cream puff you ever saw, then it begins to float down like a sigh, flowing gently as chiffon … it does a little zig zag of a curtsy and alters course to head for the stage, where it makes a perfect, perfectly genteel three-point landing. So much for terror.”9

At the pinnacle of his reign, Webber, now serving as his own producer, wrote a show called Aspects of Love. On the Walter Kerr scale of stage bakery, it would probably amount to a heap of shapeless, tasteless baking power. Ironically, the composer tried telling an old-fashioned tale sans laser beams and fog machines. Vacillating Tim Rice, perhaps still smarting over his rejected “Memory” lyric, first said yes to the project, then no. Without Rice, Aspects unleashed a soggy sea of anemic melodies and some of the most non-existent lyrics ever written. It brings into grave doubt the listening abilities of the English, who were said to have embraced it upon first hearing when it opened to divided notices in London. Aspects was totally snubbed by the annual Olivier theatre awards, failing to receive a single nomination.

When Webber tried getting the Americans to embrace it, Kevin Kelly of the Boston Globe was left in utter shock, writing, “Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Aspects of Love has come to town with the hope of pleasing critics who hated the mechanical glitz of The Phantom of the Opera (not to mention Cats and Starlight Express). It was thought to be a chiselled cameo, a light tangle of romance and sex rather than melodramatic torment through a glass darkly…. But as the opening song in Aspects of Love has it, ‘Love changes everything.’ On the Broadhurst stage Aspects instantly turns affection to aggravation, enthusiasm to ether.”10

The original cast CD is rife with ponderous first-draft twaddle, with half-composed songs sliding off into recitative purgatory. Even the big ballad, “Love Changes Everything,” warbles on like a windy old church hymn stripped of verse. Alas, that turgid Sunday school tune belongs back in Sunday school. Further observed the rueful Kelly, “After a wildly successful career (with, I think, deserving acclaim for Jesus Christ Superstar, Phantom of the Opera, and as the British say, pots of gold) Andrew Lloyd Webber now looks like a beggar. His talent is being more severely questioned than ever before. Is he just a hat-in-hand manipulator, an exploitive on-the-run tunesmith, or really an honest contributing member of musical theatre? Aspects of Love suggests the former, but then, luck changes everything.”11

Does it ever. The British did not hear music for very long, either, and Aspects shuttered early on the West End. According to The Times, Mr. Webber had purposely opened Aspects in London rather than New York in order to escape the likely wrath of his nemesis, Frank Rich. Said executive producer Pete Wilson, “British critics don’t close shows.”12 Nonetheless, those same critics were blamed for the fast fade of Aspects. The Webber magic was suddenly losing levitation. If the public was tiring of spectacle, neither was it in any mood for a belabored sung-through story of intermingling amoral relationships. On Broadway at the Broadhurst, it lasted barely a season.

Cameron Mackintosh did not build his fortunes exclusively on the efforts of Andrew Lloyd Webber, whom he called “the most talented man whom I shall ever work with in my life.”13 He also had in his stable the formidable French team of Alain Boublil (lyrics) and Claude-Michel Schonberg (music), whose musical Les Misérables Mackintosh had seen during its uncertain infancy in Paris in 1980. He fell in love with its rather traditional music, and he reshaped the show for British audiences—before whose raving admiration it opened in 1985—by implementing script changes and adding a prologue and five news songs. And he ballyhooed it into a huge international hit. Across the Atlantic, it was greeted with the usual ambivalence. Clive Barnes found the songs “monotonous”; Howard Kissel, “drivel”;14 Frank Rich, “profligately melodious.”15 On balance, the show won over a slight majority of the media judges. “It is a smash,” declared Variety’s Richard Hummler. “Magnificent stagecraft is joined to an uplifting theme of heroic human commitment and to stirring music.”16

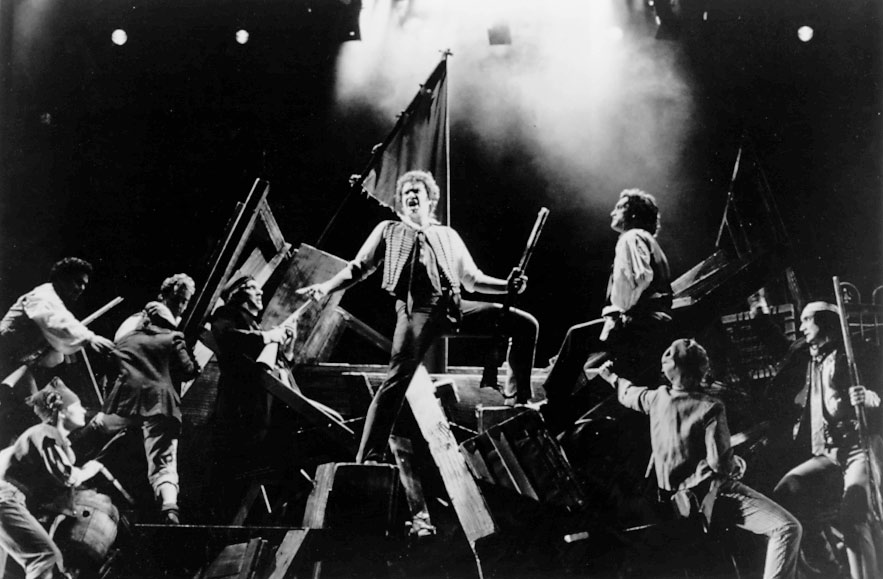

Les Mis is an infinitely inspiring achievement—simply one of the great musicals of the twentieth century. It builds heroically on the transforming power of compassion and forgiveness, and it is a triumphant affirmation of all things theatrical and life-affirming for which Oscar Hammerstein stood. First and foremost, it is a well made musical play. Secondly, its strong, classically nuanced score effectively propels the story forward, even though in cast album format the mediocre numbers pale on their own. What compels us the most is the spiritual journey of Jean Valjean, at the outset a petty thief spared a return to prison by a compassionate priest who, instead of turning him in for lifting some Chinaware from the chapel, tells the police it was a gift. Valjean then goes forward to similarly forgive, aid and inspire others, including a young brigade of French revolutionaries who fail in their quest to bring down the government. Ultimately, we are moved by the imagery of the oppressed struggling to break free, and by their penultimate song of faith that their cause will one day prevail. The first-rate stagecraft puts us there; the drama is bold and believable and complete. That Les Mis has won the hearts and souls of millions around the world, and continues to do so in return engagements, is in itself good news for the future of a medium that more often of late has wallowed in social decay.

Michael Maguire, at the center of a student revolt in Les Misérables.

Boublil and Schonberg gave Mackintosh another epic work of history to market worldwide in their extravagant opus Miss Saigon, fashioned loosely after Madame Butterfly and set in the final days of the Vietnam war. It nearly allowed for the bombing of the theatre, probably just too expensive for Mr. Mackintosh’s budget. So he settled for the landing of a helicopter on stage to dramatize the tense final moments of the American evacuation of Saigon as invading Communist forces ring the city.

“The helicopter has finally landed on the Broadhurst theatre,” wrote Laurie Winer in the Los Angeles Times, “and, as promised, it is the very best helicopter that ever played a Broadway house. What we did not expect from Miss Saigon, perhaps, was the awful power of the scene, the stunning agony of the Saigon evacuation in 1975, with soldiers scrambling into the big chopper and Vietnamese rioting to climb aboard, only to be left clinging on the cabin fence of the U.S. Embassy.”17

Mackintosh exploited this impressive engineering feat for theatrical suspense, holding it off until midway in act two. The illogical placement, accomplished during a forced flashback scene, reflected a major problem with Miss Saigon. For all of its sporadically gripping history, this momentous musical becomes a slave to its own calculated excesses. Another incongruity was the second act eleven-o’clock blockbuster, “The American Dream,” a fabulous neon-lit sendup of Yankee consumerism, complete with Cadillac car as centerpiece, elevated to bombastic irrelevance in a manner that would please the great Ziegfeld himself.

The musical’s rambling narrative bears a structural heritage to Show Boat and gives it a certain intangible stature. To its disadvantage, however, Miss Saigon must ride the hollow weight of an implausible romance between a Saigon prostitute, Kim, and her GI john, Chris. Once separated after Chris is evacuated in the helicopter, unaware that he has impregnated Kim, the two are free to lyrically long for each other, and the lovely hooker never lets up in this department. Her lonely plight does epitomize some terrible truths about that tragic war; she is forced to commit murder in an act of political defiance, in order to retain custody of the son she conceived in the brothel with Chris, and in the end, faced with a visit by Chris and his new American bride, Kim takes her own life in order to insure a future for the boy with his real father.

This precarious proposition fails to fuel the libretto with natural force, so we are left to find our pleasure in the politically charged subsidiary scenes and amidst the sleaze of Vietnamese night life and American-inspired greed. What Jeremy Gerard of Variety called “one of the baser and cynically exploitive musicals of our time, a girlie show with a phony conscience,”18 what Laurie Winer termed “engaging…insulting…never boring,”19 is, nevertheless, a musical that now and then rises, as few do, on the terror and heartbreak of its most historically traumatic moments. To experience this is to come face to face with the theatre’s ultimate power. Moreover, not since West Side Story had there been so dramatically compelling a score, a score so varied in mood from lyrical to raucous, and of sweeping orchestral passages of such cinematic force.

The producer, Cameron Mackintosh, ruled the box office for a heady 15-year spell, and still rules the box office with the same four shows. Sir Cameron and Sir Andrew, knighted by the queen of England for their sterling contributions to the economy, saw their most prop-heavy shows sell the most tickets. And when either the props or the scripts and songs stopped working wonders, they would try pointing out that, really, they had never exactly set out to blow the world away with floating staircases and falling choppers. And so they granted that small could be fine and beautiful, too. What to do, however, after giving the public the spartan Aspects of Love and getting hissed at in return? Forge ahead with Aspects II, or more big rig construction?

Sir Andrew opted to recall the hard hats. He pounded out a slavishly literal adaptation of Billy Wilder’s 1950 screen classic, Sunset Boulevard. At least in so doing, Webber and his collaborators, Don Black and Christopher Hampton, retained the taut structure of Wilder’s savagely witty tale. Critically lambasted when it first opened in London, following changes the musical moved to New York, there to be awarded with split notices, most everyone agreeing on two big attractions: Glenn Close, cast as Norma Desmond; and her grand old automobile, an item coveted (in the story line) by none other than Cecil B. De Mille when one of his underlings calls the Desmond residence.

Sunset Boulevard won a few Tonys, but not enough customers during an extended New York run to leave town flush when it went out on tour, sans automobile and heavier set pieces. Close was out and Petula Clark was in when the show came out to the West Coast, by which time, according to bi-coastal critics, it had much improved. Most striking about the production was a skeletal first act building towards a rarity in musical theatre—an actually much stronger second half. Almost everything after intermission is superior, including the glaringly uneven score, which then delivers its two great moments: the surreal “Too Much in Love to Care,” sung by characters Joe Gillis and Betty Schaefer on a vacant soundstage reminiscent of a Gene Kelly movie; and “As If We Never Said Goodbye,” sung by Ms. Desmond upon her flamboyant arrival at the Paramount lot, where she is reverentially greeted by gawking still-employed admirers from the past. The latter song offers one of the most mesmerizing moments to be spent in a theatre, though in the west coast tour perhaps it was the extraordinary coincidence of Ms. Clark, herself not heard from for many years, playing Ms. Desmond which gave this unforgettably rhapsodic song such double-edged power.

On the fundamental level of dramatic entertainment, Sunset Boulevard delivers resoundingly well. So, why did it fail to stay around for years and years like other Webber blockbusters, either in New York or London town? Maybe in a word: underdevelopment. You could argue that Sir Andrew made a fatal mistake by producing the show himself; that, had he lured Mackintosh into supervising the project, he and his cohorts might have been pushed towards a more original or consistently engaging treatment, or to supply stronger songs overall. Particularly weak in the music department is Webber’s flaccid appropriation of American jazz. And the literal treatment tended toward the obvious: Stage characterizations bordering on the one-dimensional paled next to their film counterparts. Notwithstanding these reservations, here is a musical that is hard to ignore, and the compelling story it tells is likely to keep it on the boards for years to come.

Webber next declared himself newly committed to an even kinder, gentler musical. In protracted collaboration with Alan Ayckbourn, he went back to work on their 1975 flop, By Jeeves, based on the stories of P.G. Wodehouse, and presented it in his home country to promising critical endorsement. High on the euphoria of opening-night cheers, Webber told Time Out, a weekly British entertainment magazine, “The days of the operatic musical may well be numbered.”20 His shoestring staging of Jeeves, declared a hit in England before they decided it wasn’t, did not strike the same sentimental chord with American reviewers when Webber brought it, like a child in need of special handling, to the Goodspeed Opera House, itself a safe retreat for the fallen giant of Big Apple monster hits. Visiting critics from New York were quick to recognize a charming set of songs attached to an evening of jokes and vaudeville bits they didn’t much like. “Can a Lloyd Webber show fly if the scenery doesn’t?” asked Ben Brantley, noting isolated pleasure for the songs. “Simple, cheerful ditties are not what Mr. Lloyd Webber usually aspires to.”21

Variety’s Matt Wolf fell in love with the score, “the evening’s most attractive aspect … with ‘Travel Hopefully’—Lloyd Webber in Stephen Schwartz mode—heading the list of songs I would gladly travel to hear.”22 Another gem, and there are several, is “Half a Moment,” which lifts the heart with the effortless rapture of a Richard Rodgers melody. It is all we can ask of any composer, with or without falling chandeliers. By Jeeves flirted with a New York opening, its producers fondly eyeing the Helen Hayes Theatre for a spring 2000 curtain. It toured a few regional venues without strong success, adding to its portfolio additional praise and scorn. And in the year 2001, it finally made it to Broadway, where it failed to click.

Webber’s next project, the Harold Prince directed Whistle Down the Wind, was the first of his shows ever to be premiered outside London. Enthusiastic D.C. crowds greeted its world premiere at the National Theatre, but only a few critics shared the enthusiasm. Some panned the production, citing major “second act problems.” Fearing a hostile New York press, into whose clutches the show was headed, Webber aborted the planned opening, took his latest erector set back home and evidently made it a more complex structure before trying it out on his fellow countrymen. “Does Whistle Down the Wind mark the end of the British musical boom?” asked Variety. “While one certainly hopes otherwise, it’s difficult not to feel that the levitating freeway of Peter J. Davison’s oppressive and rather scary set isn’t the only thing headed nowhere…. This Whistle takes a promising idea and then so systematically botches it that one’s primary emotion is dismay.”23

Another botch job in the works was Sir Cameron’s latest venture, Martin Guerre, from the team who gave us Les Misérables and Miss Saigon. A kind of singing albatross that hung around Mackintosh’s neck for nearly ten years, its London opening was postponed for new orchestrations and other last-minute adjustments. When finally the moment of reckoning came, Guerre faced a savage reception. Among the more perplexing failures noted by the incredulous reviewers was that the element of suspense contained in the source material had been entirely deleted.

Loaded with loot and obsessed with making a heavy bird fly, the most successful producer who ever lived shut down Martin Guerre for yet more revisions. It reopened months later and still failed to fool the public. After languishing on the boards another twenty months, Guerre closed down a second time, seven million dollars in the red.

More rewrites, an almost totally new set of songs, and in 1999 it faced opening night number three. A sympathetic Matt Wolf, critiquing for Variety, expressed modified admiration. “It’s third time lucky, in every area except the fundamental one of affect, for Martin Guerre, the long-running financial failure (and Oliver Award Winner) that has been resurrected more times than the musicals errant hero…. For all the onstage savvy, Martin Guerre continues to buckle under an inbred ponderousness that drags the tale down even when the voices and amazingly full-throated cast come together to soar.”24 Second only to unpredictable weather patterns are the theatre fortunes of big-time producers.

The British Boy Wonders had not put up a successful new musical in nearly ten years. In 1998, when Webber’s Sunset Boulevard closed on both sides of the Atlantic, suffering losses estimated to reach $50 million, a revival of Jesus Christ Superstar, also produced by Mr. Webber, resurrected neither the savior nor the composer, and it closed early the same year, having recouped about 15 percent on a $6 million investment. Massive staff layoffs ensued at Webber’s London producing arm, Really Useful. The composer put his wine collection on the auction block, where it was projected to yield a cool $3 million. And his Belgrade home at Eaton Square, valued at a handsome $25 million (chandeliers presumably not included), was offered to the highest bidder.

Mackintosh would continue pouring millions into his do-or-die obsession. “I think [Martin Guerre] could be Claude-Michel’s finest score,”25 he told an Associated Press reporter. Was it simply a matter of misguided infatuation with material that no amount of showmanship could overcome? “Listen,” he told Variety’s Matt Wolf, “whether or not Martin Guerre is one of those [blockbuster] shows, we won’t know for 10 or 20 years. If the theatre were only driven by how much money a show made, we would have no theatre.”26 For the producer who had casually juggled huge international hits in the palm of his hands, the new century beckoned ominously. Guerre was slated to open on Broadway in the spring of the new millennium. En route to a an aborted premiere, it played the Ahmanson Theatre in Los Angeles to large, ostensibly polite subscription-heavy audiences.

Some of them were no doubt left mildly aghast at the clumsy enterprise, surely one of the most dubiously constructed and difficult-to-sit-through musicals ever put on the boards. Only the most religiously insecure are likely to find solace in its theologically oppressive premise, centered around a drought assumed to demonstrate the wrath of God, and a man, Arnaud du Thil, who pretends to be Martin Guerre, returning to his wife after seven years and ending the rainless ordeal (as evidently fakes can also do) only to be challenged by the real Guerre who shows up to bring down act one’s curtain. If only they had told the story with the linear suspense of the original tale instead of falling victim to their obsession with its medieval implications (as metaphor for contemporary global conflicts), none of which have much resonance with today’s audiences. With all the millions Mackintosh had spent on rewrites, why he failed to address such a fundamental dramatic issue remains a puzzle. A few quite lovely songs do break through, like welcome rays of sunshine over a blighted landscape.

Barring a box office turnaround, years from now Mr. Mackintosh may still be ordering up yet better orchestrations for Guerre, presiding over cast changes, consulting with designers and hydraulic lift operators, and polishing off press releases touting impressive new script changes and song interpolations by famous-at-the-moment artists guaranteed to pull in the crowds and prove the critics wrong, once the new version opens. Were all new ill-fated shows so lucky. Getting that kid to grow up can drive a producer nearly nuts.