FLEX, BEND, STRETCH

FLEX, BEND, STRETCHFor most people, grasping a pen from an outstretched hand, walking up a flight of stairs, or riding a bicycle seems a simple task. At one point, though, these skills required tremendous mental effort. It takes a baby months to learn to coordinate muscles, joints, and the sense of balance first to crawl, and then to master the antigravity circus of walking upright. During those early months, figuring out how to keep the body balanced, both at rest and in motion, requires fierce attention. Even so, the child toddles and falls a lot before learning the basics of walking.

Time passes, but still, the most basic of body movements arise from the brain directing an amazing, complicated symphony of three basic functions: movement of individual muscle fibers, coordination of muscle groups, and balance.

FLEX, BEND, STRETCH

FLEX, BEND, STRETCHMuscles move in response to the brain’s conscious and unconscious orders, executed along nerve fibers. Electrochemical signals cause muscle fibers to contract. Even when you extend an arm or a leg, the process works only when the fibers contract—nerve signals never cause a muscle to stretch itself. These contractions act like binary digits: Muscle fibers either contract completely, 100 percent, or not at all. When your body needs extra strength, for lifting something heavy or twisting a stubborn jar lid, the brain recruits more and more muscle fibers to add their contractions to the existing total and increase the force your body applies.

Muscles work in groups. Shooting a basketball, for example, calls upon the brain to orchestrate the muscles of the fingers, hands, wrists, arms, shoulders, legs, thighs (bend your knees on those free throws!), and so on. The result, at least for a professional basketball player, is a smooth, well-coordinated movement that flows in properly executed order through muscles and joints to direct the basketball through the hoop. Without the brain’s coordination of the sequence of neural firing, the ball might miss the rim, or even the backboard.

The brain could not pull off this amazing feat without a well-developed sense of balance. It’s the body’s response to gravity that keeps it upright. Without stable posture, muscle fiber contractions to reposition the body would have no foundation, no reference point. A dizzy or wobbly basketball player would never lead the league in scoring.

MOTION CIRCUITS

MOTION CIRCUITSJust how the brain coordinates movement became better understood in the late 19th century when British neurologist John Hughlings Jackson examined patients with epilepsy. He noticed that, in some patients, the convulsive movements associated with epilepsy seemed to flow in sequence from one body part to another. He concluded that muscular tics and jerks arose from the disorder affecting first one brain region and then another. The obvious conclusion was that discrete brain regions control movements in particular body parts.

Today, we know that most of the brain’s circuitry is involved in both voluntary and involuntary movements. Key components include huge portions of the cerebrum, which houses the motor (movement) cortex; cerebellum; basal ganglia; brain stem; and the spinal cord, which not only carries signals to and from the brain but also organizes and responds to a variety of signals from the body’s periphery. Most, if not all, of these parts of the nervous system work together to create movement. Movement is seldom the result of a single muscle’s activation. Touching your nose with your forefinger activates muscles in your fingers, hand, arm, and shoulder, as well as your eyes. Executing the same motion while dizzy may call on other muscles to compensate.

The spinal cord contains about 20 million axons. These nerve fibers, as well as those in the brain stem, neck, and legs, respond to gravity to keep the body stable and upright. Neurons in the brain stem and cerebellum react to slight changes in body position to automatically contract the right muscles in the right amount at the right time to maintain an upright posture. Damage to neurons in the cerebellum often announces itself by affecting the ability to stand upright for any length of time. Long-term abuse of alcohol can manifest itself in the cerebellum, resulting in an unsteady gait—or worse. Likewise, damage to crucial neurons from Parkinson’s or stroke may impede movement in a variety of ways, from muscle rigidity to lack of balance. Certain health conditions, medications, and inner ear problems also affect the body’s ability to maintain balance.

HOW LOW CAN YOU GO?

HOW LOW CAN YOU GO?Motor skills tend to degrade with age. With advancing years, it takes more time to get moving. Once under way, movements take longer to execute, and they lose some of the fluidity of youth. Older joints tend to lose flexibility, growing more rigid.

Science has discovered that age itself is not to blame. Rigidity and loss of flexibility, or range of motion, in joints stem from lowered levels of physical activity associated with age, as well as health conditions such as arthritis. Inflexibility can take hold at virtually any age. However, diet and exercise can help maintain range of motion, and even restore some that has been lost.

A balanced diet, rich in antioxidants, is crucial to maintaining maximum joint movement. Growing evidence points to vitamin C playing a singularly important role. Not only is this vitamin, plentiful in citrus fruits, an excellent counterweight to destructive free radicals, but it also helps the body construct proteins found in joint cartilage.

Good exercises to maintain flexibility include stretches, which can be incorporated into a regular workout routine or performed by themselves. Stretching also has the added benefits of helping prevent injuries caused by muscle tightness and of reducing stress.

Tai chi, yoga, and Pilates classes can increase flexibility as well as balance. If you don’t want to commit to a regimen of classes with a group, you can do some simple stretching exercises at home.

Try these:

Warm-ups. Cold stretches can cause muscle injuries. The best time to stretch is when muscles have already done some basic work and begun to heat up with energy and blood. So start with five to ten minutes of walking, pedaling on a stationary bike, or doing some other simple exercise.

Warm-ups. Cold stretches can cause muscle injuries. The best time to stretch is when muscles have already done some basic work and begun to heat up with energy and blood. So start with five to ten minutes of walking, pedaling on a stationary bike, or doing some other simple exercise.

Spine stretches. Lie on your back on the floor with your arms and hands at your sides. With your legs straight, bring your feet up in the air. Try to raise them far enough to angle your feet back over your head. Count to five, lower your legs to the floor, and repeat ten times. This stretches your spine, an excellent way to minimize the risk of back injury.

Spine stretches. Lie on your back on the floor with your arms and hands at your sides. With your legs straight, bring your feet up in the air. Try to raise them far enough to angle your feet back over your head. Count to five, lower your legs to the floor, and repeat ten times. This stretches your spine, an excellent way to minimize the risk of back injury.

Seated stretches. Sit on the floor with your legs crossed and your back straight. Lean forward until your back is arched and your head and neck are parallel with the floor. Count to ten, then revert to your starting position. Repeat five times. When you’re done, stand and get loose.

Seated stretches. Sit on the floor with your legs crossed and your back straight. Lean forward until your back is arched and your head and neck are parallel with the floor. Count to ten, then revert to your starting position. Repeat five times. When you’re done, stand and get loose.

Trunk twists. Stand with your hands on hips and arms akimbo. Your feet should be a short distance apart and not move during the exercise. Twist your trunk slowly to one side and look behind you. Hold that position for five seconds. Then twist the other way and repeat. Do this a few times to stretch your trunk.

Trunk twists. Stand with your hands on hips and arms akimbo. Your feet should be a short distance apart and not move during the exercise. Twist your trunk slowly to one side and look behind you. Hold that position for five seconds. Then twist the other way and repeat. Do this a few times to stretch your trunk.

Leg lifts. Stand next to a desk or table, positioned to one side of you. Grasp the edge with one hand. Slowly raise one leg until it is parallel to the floor. Lower the leg and repeat with the other leg. Do this ten times with each leg to boost flexibility in the hips.

Leg lifts. Stand next to a desk or table, positioned to one side of you. Grasp the edge with one hand. Slowly raise one leg until it is parallel to the floor. Lower the leg and repeat with the other leg. Do this ten times with each leg to boost flexibility in the hips.

If those exercises are too strenuous, you might try the following easier ones. Try repeating these three to six times at first, and then add more repetitions or go on to some of the previous exercises:

Reach for the sky. Sit or stand so your back is straight. Raise your arms above your head and stretch for the ceiling. Return your arms to your sides to relax for a moment.

Reach for the sky. Sit or stand so your back is straight. Raise your arms above your head and stretch for the ceiling. Return your arms to your sides to relax for a moment.

Side to side. Stand tall with your feet apart and your arms at your sides. Bend to one side, letting your hand drag along your thigh toward your knee. Then straighten up. Bend to the other side, and repeat equally on both sides.

Side to side. Stand tall with your feet apart and your arms at your sides. Bend to one side, letting your hand drag along your thigh toward your knee. Then straighten up. Bend to the other side, and repeat equally on both sides.

Toe loops. While sitting in a chair, keep one leg bent while straightening the other before you. Stretch your toes toward your head and then downward. Then slowly circle the foot at the ankle. Repeat with the other foot.

Toe loops. While sitting in a chair, keep one leg bent while straightening the other before you. Stretch your toes toward your head and then downward. Then slowly circle the foot at the ankle. Repeat with the other foot.

Leg extensions. Sit in a chair with your knees bent a bit. Straighten and stretch one leg before you, then let it drop. Repeat with the other leg.

Leg extensions. Sit in a chair with your knees bent a bit. Straighten and stretch one leg before you, then let it drop. Repeat with the other leg.

Elbow loops. Sit or stand with your elbows bent and your fingertips on your shoulders. Slowly rotate one of your elbows in a big, backward circle. Repeat with the other elbow. Or try simply bending and straightening the elbow again and again, which helps build arm flexibility.

Elbow loops. Sit or stand with your elbows bent and your fingertips on your shoulders. Slowly rotate one of your elbows in a big, backward circle. Repeat with the other elbow. Or try simply bending and straightening the elbow again and again, which helps build arm flexibility.

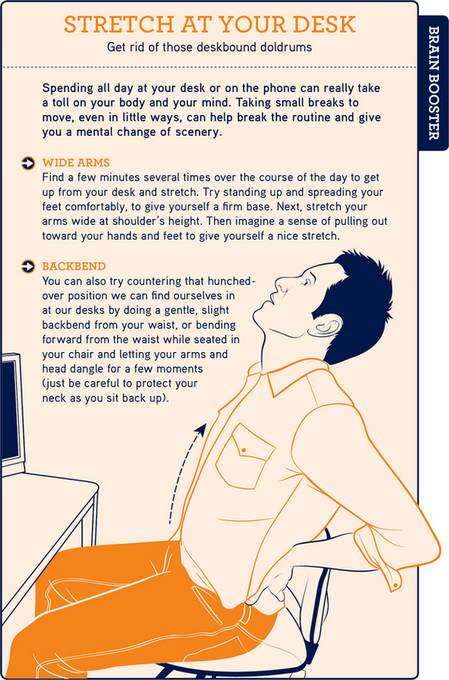

Waist watchers. Lean slightly forward while sitting in a chair with your knees bent and your feet on the floor. Bend forward slowly from the waist and stretch your hands toward your feet. Then slowly straighten and relax. After you’ve tried this exercise for a while, switch to a trunk twist. Put your right elbow on your left knee by twisting at the waist. Then straighten up, pause, and shift your left elbow to your right knee.

Waist watchers. Lean slightly forward while sitting in a chair with your knees bent and your feet on the floor. Bend forward slowly from the waist and stretch your hands toward your feet. Then slowly straighten and relax. After you’ve tried this exercise for a while, switch to a trunk twist. Put your right elbow on your left knee by twisting at the waist. Then straighten up, pause, and shift your left elbow to your right knee.

Be sure to breathe regularly, without holding your breath at any point. Don’t bounce as you stretch, as bouncing tightens muscles and can cause minute scarring in muscle tissue. If you find any unpleasant level of discomfort from any of the exercises, stop immediately and try again another day. Persistent pain caused by simple exercises can be a sign you should see your doctor.

In addition to the previous exercises, you can invent your own or make use of your surroundings to promote strong balance

Tennis star Martina Navratilova, now in her mid-50s, likes to stretch with a foam roller, the kind sold in a sporting goods store. The roller stretches the fascia, connective tissues that surround the muscles, and improves blood flow, she told AARP.

Stephen Jepson, in his early 70s, has converted his yard into a playground to keep his body and brain sharp. Jepson, featured in a video in the Growing Bolder Media Group’s series celebrating active senior citizens, believes the key to staying mentally fit is to return to the playgrounds of childhood. Jepson challenges the movement-coordinating circuits of his brain by riding an elliptical bicycle, walking slack ropes strung between trees, hopping barefoot from rock to rock, and otherwise providing new and unusual stimulation to his motor cortex. The practice not only has maintained his balance and agility, he said, but has also sharpened his memory.

IT ISN’T EASY BEING UPRIGHT

IT ISN’T EASY BEING UPRIGHTThe human ear carries out two important jobs. One, of course, is to translate vibrations into sensations the brain constructs as sounds. The other is to coordinate the body’s position to keep it in balance.

The latter function relies on the vestibular system, which along with the cochlea occupies the inner ear. The vestibular system comprises a series of fluid-filled tubes called the semicircular canals, plus the vestibule, a space that connects the canals with the cochlea. Special sensory cells that detect motion occupy the vestibule and semicircular canals and send signals via nerve fibers to the pons and medulla oblongata.

The neural circuitry of balance ties together sensations in the ear with vision and other sensory systems. The brain uses the eyes and specialized sensory cells in the feet to gather information about the position of the body in space. The vestibular system’s fluid-filled tubes detect motion of the head, both in a straight line and in a curve. Fluid movement bends sensory neurons in the tubes, initiating electrical signals in the connecting nerve fibers. The brain swiftly integrates this incoming information and sends signals to the arms, legs, trunk, and other body parts to shift in reaction to changes in body orientation to the ground. The brain also directs the movement of the eyes to redirect their gaze, when necessary, to provide feedback as the body moves. So, for example, when you stumble, your eyes flash to the ground before you.

Proprioception is the brain’s unconscious sense of the body’s motion and spatial orientation. The system is amazingly complex and interconnected, yet you probably never give your balance a second thought—until you start to fall.

Anthropologists have noted an interesting fact about the vestibular system. Humans evolved over millions of years to walk upright on ground. This development freed the hands for carrying tools, such as axes, clubs, and spears that could aid in the hunt for food. Differences in the ability to coordinate upright movement may account in part for the extinction of humanity’s evolutionary cousins, the Neanderthals. Homo neanderthalensis shared space with Homo sapiens until the former disappeared about 30,000 years ago. Recent examinations of Neanderthal skulls revealed that, compared with modern humans, Neanderthals had smaller vestibular systems. They would likely have had a less developed sense of balance and less agility. That could have made Neanderthal second best at hunting game, an evolutionary disadvantage in the long term.

As previously noted, aging causes the structure of the ear to change. Most notably, the eardrum thickens, which not only may affect hearing, but also impacts balance.

Maintaining balance into old age is a key component of enjoying life. Journalist Scott McCredie, who wrote a book about the human sense of balance, said it’s vital to challenge the sense of balance to keep it sharp. “[As] we move into our 60s … we can’t afford not to think about it,” he wrote. “Not just to prevent a potentially lethal fall, but to be able to continue moving gracefully through the world, to stay glued to the tightwire of life.”

Two body systems linked to balance—vision, and the sensitivity of cells in the feet that inform the brain about the body’s position—also typically decline with age. In addition, loss of muscle mass and less flexibility in the limbs mean that when an aging body begins to totter, the brain must rely on weakened tools to avoid a fall. Each year, one in three Americans older than age 65 loses balance and suffers a fall. Brittleness in elderly bones often causes them to break in such falls, sometimes with catastrophic results.

The sense of balance has two forms: static and dynamic. The former keeps the body upright when still. The latter maintains balance while the body changes its relationship with the surface of the Earth, as when climbing a hill or stairs, or turning a street corner on a bicycle. Both begin to gradually erode beginning in the body’s third decade. Unless the deterioration is checked by deliberate steps, the result often is dizziness or loss of balance later in life. Compromised balance may not seem like much of an impediment, but it can interfere with driving, walking, and even sitting upright. People with continuing troubles with balance often have trouble holding a job.

EASY DOES IT

EASY DOES ITChronic dizziness increases the odds of falling by two to three times. Dizziness is classified in four types, all of which become more common with advancing age:

Loss of balance; unsteadiness; a feeling of being about to fall despite normal muscle strength. Disorders in the inner ear and the cerebellum, such as damage caused by alcoholism or stroke, can bring on this condition. So too can the use of too much sedative or anticonvulsant medication, as well as nerve disorders that affect the sensation of the position of the legs.

Loss of balance; unsteadiness; a feeling of being about to fall despite normal muscle strength. Disorders in the inner ear and the cerebellum, such as damage caused by alcoholism or stroke, can bring on this condition. So too can the use of too much sedative or anticonvulsant medication, as well as nerve disorders that affect the sensation of the position of the legs.

Faintness. This feeling of impending blackout can stem from dehydration, nervous system disorders, abnormal heartbeat, and adverse reactions to blood pressure medication.

Faintness. This feeling of impending blackout can stem from dehydration, nervous system disorders, abnormal heartbeat, and adverse reactions to blood pressure medication.

Vertigo. This feels like movement in the body or the body’s surroundings, despite both being at rest. Causes can include middle-ear infections, migraines, decreased blood flow to the brain, motion sickness, or something as simple and transitory as a sudden movement of the head.

Vertigo. This feels like movement in the body or the body’s surroundings, despite both being at rest. Causes can include middle-ear infections, migraines, decreased blood flow to the brain, motion sickness, or something as simple and transitory as a sudden movement of the head.

Lightheadedness. This vague feeling may arise from a panic attack, hyperventilation, depression, or other mental disorders.

Lightheadedness. This vague feeling may arise from a panic attack, hyperventilation, depression, or other mental disorders.

Exercises can maintain and even improve balance. Such exercises work the hips, knees, ankles, and feet. They also challenge the neurons of the vestibular system to keep it firing and wiring. These exercises require no special training: They’re as easy as balancing on one foot for as long as you can, or walking by placing one heel directly in front of the toe of the other foot and continuing to walk in a straight line.

BRAIN INSIGHT

The peaceful benefits of a martial art

Legend says tai chi began when a 12th-century Taoist monk fled the cities to find peace in the mountains and wondered how to protect himself. The monk, Zhang Sanfeng (or Chang San-Feng), studied martial arts at his monastery, but an epiphany allowed him to move beyond his teachers. Zhang saw a bird and snake fighting. Instead of charging one another, the antagonists adjusted their movements to penetrate the adversary’s defenses. Zhang saw that moving with an opponent’s force, instead of opposing it, could be the foundation of a new martial art based on mimicking animals. Thus was born tai chi chuan, or “supreme ultimate fist.”

Despite the martial name, tai chi today is practiced most often by those seeking inner peace instead of victory in combat. The dancelike, deliberate movements aim to bring mind, spirit, and body into alignment and operate them under a universal source of energy, called ch’i.

The discipline has a mystic, Eastern aura, but you don’t have to understand how tai chi works to benefit from it. Its gentle, stress-free movements can be done at any age, but it has particular benefits for the elderly: Regular workouts improve balance, flexibility, and mobility, reducing the risk of falls. They may even combat depression.

Physical therapists Marilyn Moffat and Carole B. Lewis, authors of Age-Defying Fitness, suggest that before beginning a regimen to improve balance, you should assess your current state. They suggest the following exercises, to be performed near a table or some other sturdy piece of furniture you can lean on or grab as needed: Begin by putting on a pair of flat, closed shoes. Stand straight with your arms folded across your chest. Lift one leg until the knee is bent at about a 45-degree angle. Close your eyes and begin to time yourself; use a stopwatch if you have one. Stay balanced on one leg. Stop timing the exercise as soon as you uncross your arms, bend to one side more than 45 degrees, touch your bent leg to the floor, or move your foundation leg. When you’re done, switch legs and start again.

Take your times and compare them to your age group. The norm for people 20 to 49 years old is 24 to 28 seconds. It drops to 21 seconds for people in their 50s, 10 seconds for those in their 60s, and 4 seconds for those in their 70s. Most people age 80 or older cannot count off even one second.

File away your numbers for comparison after dedicating yourself to the following exercise: Once again while wearing flat, closed shoes, stand near something you can grab. Plant your feet shoulder-width apart with arms stretched straight in front of you and parallel to the floor. Keep your eyes open. Lift one foot behind you by bending your knee about 45 degrees. Freeze for at least five seconds, if you can. Do this exercise five times, and then do exactly the same with the other leg. When you feel you have begun to make improvements, continue, but with your eyes closed.

You can practice this skill at any time during the day, such as when you’re getting ready for work or bed. Incorporate a one-leg stand into brushing your teeth or combing your hair. (Best not to mix this exercise with a shaving razor, however.)

Another useful exercise boosts the strength of ankles, legs, and hips to help the body better deal with the potential dizziness of suddenly standing after sitting a long time. To get the most out of this exercise, sit up straight on something firm without having your back touch anything. Rise until you stand straight, and then sit again as quickly as you can without using your arms. Repeat three times at first. Over time, try to extend the exercise until you can do it ten times.

You also might specifically target the strength of your ankles by walking for a while on your toes, then switching to using only your heels.

BRAIN INSIGHT

More Than Monkeying Around

Neuroscientist Michael Merzenich at the University of California, San Francisco, has seen a brain physically change while learning a new task

Merzenich put a banana-flavored pellet in a cup and watched as a squirrel monkey extended an arm through the bars of a cage, grasped the pellet from the cup, and ate it. The test subject repeated the action dozens of times each day until it became automatic. Then Merzenich replaced the cup with a smaller one. It took a while for the monkey to fish the pellet out of the smaller cup, but it eventually mastered that skill, too. Twice more, Merzenich swapped the cup for a smaller one, until the monkey had become extremely adept at getting a banana pellet from a narrow opening by the fourth cup.

Computer images of the monkey’s brain revealed that the neural networks associated with conscious finger manipulation expanded as the monkey learned greater dexterity. However, once a monkey no longer had to think about the motions, the expanded neural networks active during the learning phase showed reduced activity. The skill moved from the parts of the brain associated with conscious thought to other parts that handled routine movements.

The learning circuits of squirrel monkey brains, and those of humans, don’t need to stay burdened with old information. To use a computer analogy, they can clear their memory after mastering a task to prepare themselves for a new one.

Tai chi, an ancient Chinese muscle-training discipline, appears to be one of the most effective systems of improving balance. Studies have shown practitioners of its slow, deliberate movements decrease their likelihood of falling. Tai chi is not only a discipline of exercise, it’s also a form of meditation; Chinese practitioners call it “mindful exercise.” Studies at the University of Massachusetts Medical School at Worcester reveal that the combination of physical and mental exercises in tai chi can lower anger, depression, and tension.

BRAIN INSIGHT

Sensors implanted in the brain can command electronic limbs

It’s not much of a stretch to go from manipulating a computer cursor with a thought, accomplished in 1998 and depicted a few years later on the television drama House M.D., to moving something more substantial.

In May 2012, a team of scientists announced that they had taught two quadriplegics to manipulate a robotic arm. The arm reached and grabbed, just like one of flesh and blood. One of the two people, a woman who had been unable to give herself a drink for 15 years, smiled broadly when she wrapped robotic fingers around a coffee cup and took a sip.

The arm receives electrical impulses from an aspirin-size sensor implanted in the motor cortex. When the test subjects imagine making particular arm movements, the sensor picks up patterns of neural firing, translates them into signals that can be read by the arm, sends them along a wire, and sets the arm in motion.

The arm rests on a shoulder-height dolly and has yet to leave the lab. Researchers at Brown University, the Department of Veterans Affairs, and the German Institute of Robotics and Mechatronics hope to develop a wireless transmission system as well as lifelike limbs that are integrated into the body.