5

Marie and the Mob

IN THE FIRST half of her life, in Paris, Madame Tussaud may be said to have lived through ‘the best of times, and the worst of times’. Her close identification with the French Revolution functions at two levels. At the personal level her account of all that she had gone through enthralled her audience, and earned her a mixture of respect and sympathy. In her long years on tour in England she was remembered as telling ‘many queer tales’ of the Revolution, and the Revolutionary relics at the core of her collection reinforced her account of her experiences. In the minds of many, her reminiscences established Madame Tussaud as a plucky survivor of traumatic times. A family friend of her eldest son, Joseph, Mrs Adams-Acton, encapsulates the widely held perception of Madame Tussaud’s colourful past at the epicentre of the Revolution:

It was difficult to realize that Madame Tussaud, clever little artist that she was, had been employed at the French court, teaching modelling in wax. How she, so closely involved in the life of the court, had yet escaped death or imprisonment was incomprehensible till one understood that the sans-culottes had found her of use to take casts of the decapitated. Amongst others, she had held in her own hands the heads of Queen Marie Antoinette, of Madame Elizabeth, and of the Princesse de Lamballe, and had taken casts of them and of many others. Her task in France had been a hard and gruesome one, and her adventures excited our sympathy.

Her first-hand, eyewitness credentials were an integral part of the fascination her artefacts held for the public. More importantly, for the vast numbers of people who saw them, they were interpreted as an authoritative record of the recent past, and were relied upon as an authentic historical narrative of the French Revolution. In 1904 the man who also propelled Baker Street to fame, the creator of Sherlock Holmes, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, in a speech at a dinner to commemorate Madame Tussaud’s arrival in England, described how the models and relics functioned in this way:

If you could conceive the position of a person living in the year 1792–or thereabouts–if you could put yourself back in the streets of Paris in those days; if you could see the King and Queen with the shadow of their dark fate upon their foreheads, see the austere Robespierre looking at them; the murderous Danton muttering. If you could see these historical scenes, and this woman take the heads of these people out of the guillotine basket to frame them in waxwork, from the skill which she had gained, if you can imagine that–and probably you cannot because few of us can imagine scenes apart from our own period–I say if you can imagine that, it would be a most extraordinary and unique and curious thing. Madame Tussaud is responsible for a definite image of one of the most terrible periods of life.

Many of the key images that continue to inform our interpretation of the French Revolution derive from the original exhibition that Curtius and Marie steered through the supremely challenging commercial conditions of Revolutionary Paris. Heads on pikes, death masks, Marat in his bath–for us these are gruesome reconstructions in the Chamber of Horrors, but for those paying a few sous to see them when they were newly moulded they were a valuable source of topical information. What we experience as history was, for the Parisian public, literally headline news.

If the two branches of the wax exhibition–the Palais-Royal salon and its counterpart in the Boulevard du Temple–had originated as innocent entertainments for all classes, in 1789 they started to assume a more serious function. Instead of being an amusing barometer of public interest, they became a register of a rapidly changing political scene. From being an invaluable reference for followers of fashion who loved to scrutinize the hair accessories favoured by the Queen, the exhibitions evolved in response to the mounting interest in current affairs. As a visual reference of the topical, in a largely illiterate society wax had the edge on print, and the adaptability of the model heads and bodies provided a particularly arresting parallel to the dramatic reversals of fortune that would see the ‘heads’ of a series of governing bodies rise and fall from power in quick succession. The potential of the medium to serve political ends meant that Marie–by now twenty-eight–found herself not merely a witness but embroiled with the epic events of 1789 that saw a reform movement turn into a revolution, and feudal respect for monarchy descend into anarchy.

In eighteenth-century France the relationship between head and body was a potent metaphor and recurring motif. In 1776 a spokesman at the Parlement of Paris had described the relationship between king and nation as like that of the head to the body. Addressing Louis XVI, he referred to him as ‘the head and sovereign administrator of the whole body of the nation’. On the eve of the Revolution the journalist and playwright Louis-Sébastien Mercier used a similar analogy about Paris. He referred to the city as ‘a head that had grown too big for its body’. Like the top-heavy hairstyles that characterized the excesses of the Ancien Régime, Mercier implied, Paris was teetering, precarious, and unbalanced.

As the relationship between Louis and his subjects became ever more strained, a power struggle was played out between Paris and Versailles. The chisels that Curtius and Marie used to remove the wax heads of those people in public life whose popularity had paled were increasingly busy chipping away at society beauties in their finery to make way for a new species of celebrity. These were men committed to radical reform–men who would translate the theories of Voltaire and Rousseau into action. In 1789, alongside Marie’s models of these literary giants, Abbé Sieyès, Mirabeau, Necker and the Duc d’Orléans took up their places as the new subjects of public homage.

Later in the same year a philanthropic doctor, Joseph-Ignace Guillotin, proposed a more humane system for public execution in the form of a machine that ‘would separate the head from the body in less time than it takes to wink’. It was not until 1792 that his theoretical proposition was put into practice, being most spectacularly employed in the regicide of 1793, an event emulated by fanatical republicans in the ritual decapitation of royal chess pieces. Decapitation dominates the iconography of the French Revolution. From the straightforward updates of Marie and Curtius’s mannequins to the drama of the tumbril, drum roll and drop as necks were severed like cabbage stalks, for the people of Paris the headless body became a grim reality of everyday life.

The guillotine, the mechanical decapitating machine linked for ever to the unfortunate doctor who had no part in its design or construction (it was largely the invention of a German piano-maker called Tobias Schmidt), was also to become inextricably linked to Marie. In the collective imagination of millions of people all over the world she is best known for modelling the scaffold-fresh heads of the most famous victims of the French Revolution. This association is largely derived from her memoirs, which make much of her first-hand experience of the atrocities of this period. The image of an innocent young woman in a blood-stained apron being forced to mould the brutalized faces of people she had known is central to the identity of Madame Tussaud. But, rather as Dr Guillotin was credited for a machine he did not construct, attribution to Marie of some of the most famous death masks and relics from this period has to date eclipsed the role of Curtius.

On the eve of the momentous events of 1789–95, Curtius deemed it prudent to leave his premises in the Palais-Royal and to consolidate in one large exhibition in the Boulevard du Temple, which remained the family home. In addition to seismographic sensitivity to currents of change–the asset upon which his exhibitions relied–Curtius had the added advantage of a good network of contacts in positions of power. He relied on being in the know in order to be in tune with public interest, and, just as he had a knack of showing the right material at the right time, similarly he made a point of fraternizing with or distancing himself from people in public life to serve his own ends. Marie would have us believe from her memoir that the eve of the Revolution marked her return to Paris from Versailles. She implies that it was because of Curtius’s inside knowledge about the impending upheaval that he coerced her into abandoning her position as pet of the palace to return to the fold. But, instead of fond farewells at the palace of Versailles, it seems more likely that the moving she did at this time was rather more mundane.

Either late in 1788 or early in 1789, they gave up the two boutiques they had rented in the arcades besides the famous Café Foy in the area of the Palais known as the Galérie Montpensier. It was no mean feat packing up all the paraphernalia and installing it all at 20 Boulevard du Temple. It was not going to be an easy fit. The sconces and candelabras, elaborate rococo looking glasses and pedestals that had been the backdrop to the tableaux of the royal family were at odds with the props used to create the atmosphere of cheap thrills in the Caverne des Grands Voleurs. But from now on the exhibition would comprise two different sections under one roof, anticipating a duality of glitz and gore that has carried through to the present-day exhibitions. The process of moving and adapting to whatever accommodation was available would stand Marie in good stead in the future. Wrapped in cotton shrouds, the dummies that had been reincarnated so many times as men and women, literati and glitterati, courtiers and criminals, according to which heads were affixed to their frames, were all carted back to the bustle of the theatre district.

However, the former happy bustle of street life had assumed a new edginess as privations started to have a corrosive effect on morale. The poor harvest in the summer of 1788 followed by one of the harshest winters in memory had drastically affected the supply of the staples of bread and firewood. The severe weather highlighted privilege and poverty. At the palace of Versailles the weather was largely inconvenient. Icy winds froze sauces en route to the King’s dining table, and the imaginative solutions to keeping warm adopted by some members of the royal household restricted normal interaction with the world. The Marquise de Rambouillet had her servants sew her into a bearskin, while the Maréchale de Luxembourg retired to a sedan chair packed with warming pans. While at court aristocrats could hibernate in comfort, in Paris the poor without fuel died cold and hungry. In spite of this, in December 1788 Louis XVI’s oppressed subjects were still loyal royalists. A few streets from her house Marie would have seen the people’s monument to their monarch in gratitude for the gift of firewood, a towering snow obelisk ‘for our ruler and our friend’. The King’s cousin the Duc d’Orléans had also made a generous donation of firewood, funded in part by a sale of fine art. Marie, however, was sceptical about the motivation for his charity: ‘By giving away large sums of money he rendered himself very popular with the people, as also by taking the democratic side of the question; his fortune being so immense that it enabled him to purchase popularity.’ But from the spring of 1789, like the snow tower made by hundreds of freezing fingers, regard for royalty was starting to melt away. At the Palais-Royal the political temperature was also starting to rise, and the King’s wayward relative was fanning the flames.

Whereas previously people had flocked to the waxworks primarily to see what and who was in or out of fashion, now the buzz was news. The national economy was a universally hot topic as a succession of finance ministers tried and failed to implement reforms that would put the country back in the black, or at least try to haul it out of the red. Finances had been dented first by the Seven Years War (1756–63) and then by French intervention in the American War of Independence (1775–83), and this, in conjunction with the prodigality and change-resistance of the King, presented a monetary and diplomatic nightmare for each of those charged with devising solutions. At the Palais-Royal exhibition the finance minister Calonne had taken up his place. With elaborate lace ruffs and a powdered wig, he was a picture of Ancien Régime elegance. In her memoir Marie described him as ‘a great favourite with the court and proportionately disliked by the people’. An exceptionally well-groomed gourmet, with a penchant for truffles and expensive pomade, he was not the best role model for belt-tightening. Certainly Marie was no fan, accusing him after his fall from grace not only of stealing ‘several objects of vertue that belonged to the nation’ but of selling them off ‘to defray certain expenses’.

By the time the exhibition had moved back to the Boulevard du Temple, Jacques Necker had replaced Calonne. With no frills and furbelows he was a lower-maintenance model, and no crony of the court. Marie noted that his appearance ‘savoured more of the countryman than of one who had been accustomed to fill the highest stations and commune with royalty’. His belief in transparency, demonstrated by his earlier publication of the Compte Rendu, a ground-breaking economic exposé of the nation’s finances, had paved the way for a popularity which in the challenging climate of the first half of 1789 meant that there was both respect for and confidence in this brilliant Swiss businessman. His conviction that the Crown was accountable to the people particularly endeared him to the public, and he also advocated tax and electoral reform. However ineffectual his efforts proved, he assumed the status of a favourite and hero.

Marie watched as the same people who patronized the exhibition–the small fry of society such as artisans, hairdressers/wigmakers, craftsmen and shopkeepers–turned into voracious consumers of political pamphlets that championed their cause. In the caste system that characterised Ancien Régime France, the Third Estate comprised the vast body of the populace, who had the least political power and who were subjected to the most iniquitous taxes on basic goods such as salt. It was these people who suffered most from the fluctuating price of bread. One of the recurrent complaints of the Third Estate expressed in the cahiers de doléances, the formal lists of grievances they were invited to submit to the Estates General at Versailles in March and April 1789, was that ‘all goods needed to support life are very dear.’ Bread was the big issue. As the price of the four-pound loaf reached a new high, domestic budgets were put under almost intolerable strain. Military convoys for the transportation of grain became a common sight, and bakers were given police protection. On the outskirts of the city, extra troops were mobilized near the customs posts in the wall that encircled it. Built in 1785 to minimize evasion of royal revenue, the high-walled enceinte was deeply unpopular. The customs posts were natural flashpoints in the violence that erupted later in the summer, when in just three days nearly all of them were destroyed.

Hollow stomachs were never a problem for the other two Estates–in reverse order of power, the clergy and the nobility. These upper echelons, comprising less than half a million people, owned two-thirds of the land, compared to a tenant class of twenty-five or so million common people. Engravings depicting the plight of the disenfranchised masses used a common imagery of oppression. Typically a peasant was shown giving an uncomfortable double piggyback to a fat noble and a cleric, or, more dramatically, he was being trampled underfoot by them. Men of letters reinforced this theme with grim metaphors. For Abbé Sieyès the nobility and clergy were to the Third Estate ‘a malignant disease which preys upon and tortures the body of a sick man’. For the historian Sébastien de Chamfort, the Third Estate were the hare, the nobles and clergy were the hounds, and the King was the hunter. With a hunting-mad king on the throne, this was particularly apt.

Occupying an expansive space between the fat cats of the old order and the teeth-chattering classes too poor to buy firewood were the rapidly growing ranks of the middle class, who were also part of the Third Estate. These employers and entrepreneurs, of whom Curtius is a prime example, enjoyed the fruits of self-made prosperity. They sent their offspring to expensive private schools, and acquired second homes, which they furnished in expensive imitations of aristocratic grandeur. Mercier marvelled at the middle-class makeovers–bell wires installed in walls for summoning servants, expensive carpets, gilt moulding and superb beds. He wrote, ‘The middle classes are better housed today than monarchs were two hundred years ago. I believe an inventory of furniture would greatly astonish our ancestors were they to return to this world.’ It is this group in particular who followed with avidity the twists and turns of the political drama that unfolded at Versailles between May and June, and which culminated in the Tennis Court Oath, when the representatives of the Third Estate declared themselves a National Assembly committed to working towards the establishing of a constitutional monarchy and the reducing of Ancien Régime privileges. There was mounting concern about the mixed messages from the King who, while seemingly compliant with the pushes for reform, was at the same time sanctioning a greatly increased military presence in Paris. French guards and foreign regiments were mobilized in and around the city.

To keep abreast of these developments, the best place to go was the Palais-Royal, which had become the headquarters of Third Estate propaganda. Here Pierre Choderlos de Laclos was one of the writers employed by the Duc d’Orléans to churn out politically inflammatory tracts. In 1783 his epistolary novel Les Liaisons dangereuses had scandalized high society and provoked waves of gossip as people speculated on the real-life identity of the amoral protagonists, and his subversive writings stirred up weighty debates. From noon until night beer flowed at the Café Flammande and brandy at the Café Foy, but it was the intake of news and views that was intoxicating. In a letter to his wife the Marquis de Ferrières, visiting from the provinces, evoked the exhilarating atmosphere:

You really can have no idea of the variety of people who regularly collect at the Palais-Royal. The sight is truly amazing…Here a man drafts a reform of the constitution, there a man reads aloud his own pamphlet; at another table someone is castigating a minister; everyone is busy talking each with his own attentive audience. I was there almost ten hours. The paths are swarming with girls and young men. The bookshops are packed with people browsing through books and pamphlets, and not buying anything. In the cafés one is half suffocated by the press of people.

Up until now the most famous orator in the Palais-Royal was a chestnut-seller. On her way to and from the exhibition, Marie would have seen this distinctive figure enthroned on his ebony seat, from where he delivered his legendary sales spiel: ‘Sirs, I have gathered to tell you that I have perfected my talent. I may not be the equal in eloquence of all those who occupy the lycée, the museums, the clubs of the Palais, but I am as zealous. They stir up the air with vain words; I prove realities. They caress the ear, I delight the palais [palate] by means of an exquisite fruit.’ But now soapbox speakers drowned out the ‘Supérieur des Marronistes’(Chestnut Supremo) with their impassioned appeals to the public to try new political ideas. From every quarter–ballad singers, salesmen, pamphleteers–there was a deluge of words.

With public interest in the political affairs of the day at fever pitch, and the woes of the nation a subject of fierce debate, people flocked to the Palais-Royal, where anti-Establishment rhetoric poured forth. The unbridled ranting amazed Arthur Young; ‘The press teems with the most levelling and seditious principles that if put in execution would overturn the monarchy, nothing in reply appears, and not the least step is taken by the court to restrain this extreme licentiousness of publication.’ Formerly the Palais-Royal had been a recreational destination, a sensation-seeker’s paradise, and time-killer’s dream; now it was the natural habitat of a new species of wild-eyed, vein-throbbing fanatic. It was the unofficial news agency, and at any one time the number of people congregating there for the latest updates could be counted in thousands. Arthur Young conjures up a vivid picture:

The coffee houses of the Palais-Royal present yet more singular and astonishing spectacles; they are not only crowded within, but other expectant crowds are at the doors and windows listening à gorge déployée [open-mouthed] to certain orators. The eagerness with which they are heard and the thunder of applause they receive for every sentiment of more than common hardiness or violence against the present government cannot be easily imagined.

Given this edgy atmosphere, it is not surprising that Curtius had decided to remove himself from the crucible of fanaticism. He was not merely an interested observer in the Third Estate cause: his keen interest extended to socializing with many of those involved, and, according to Marie, he was regularly a host to most of the key players who were committed to reshaping the political landscape of France. In her memoirs she describes the new cast of characters at the family dinner table: ‘Formerly, philosophers and the amateurs and professors of literature, the arts and sciences ever resorted to the hospitable dwelling of M. Curtius. But they were replaced by fanatic politicians, furious demagogues and wild theorists, for ever thundering forth their anathemas against monarchy, haranguing on the different forms of government, and propounding their extravagant ideas on republicanism.’ There is a symbolic contrast between the animated scenes at the wooden dining table upstairs and the sedate tableau immediately below, where the wax figures of Louis and Marie Antoinette were still seated in all their formality at the Grand Couvert, fragile figures oblivious of the growing contempt in which they were held.

Talk eventually tipped into action, and from taking passive interest in the issues of the day the people of Paris started to show their readiness to take a participatory role. The symbolic destruction of primitive effigies of those who had incurred the wrath of the people was an ominous indicator of the potential for violence. In succession, two finance ministers who had failed to implement vital reforms were murdered by proxy: in 1787 a primitive effigy of Calonne was hung, and in 1788 a makeshift Loménie de Brienne was ceremonially burned. More menacing, on account of the scale and force of the associated riots, was the mock murder of the wallpaper manufacturer Réveillon in April 1789. A casual remark by this prosperous man about worker’s wages was misinterpreted and blown out of proportion to the extent that it incited an angry mob to go on the rampage. They destroyed the printing machines and stock in his warehouses, and then moved on to ransack the luxurious Rue Saint-Antoine home of this employer who had only ever had the interests of his employees at heart. The rioters had carried a mock gallows through the streets together with a crude dummy of their foe, inviting those en route to come and witness it being hanged and burned in the Place de Grève. Little could Marie have known that this atavistic energy was but the ominous beginning of violent political activism in which the wax heads that were her and Curtius’s livelihood would play a major role, where the symbolic and the real would become interchangeable. Wax heads formerly used to celebrate heroes and decry villains, viewed for a small fee by a good-natured public, were imminently to be borne aloft in protest and in triumph, and were then supplanted by real heads on pikes, displayed as bloody trophies of murderous anger.

The King’s sudden sacking of finance minister Necker on Saturday 11 July was the spark in the powder keg. From now on there was a sense of events overwhelming people, rather than people controlling outcomes. On the afternoon of Sunday 12 July the news of Necker’s dismissal reached the Palais-Royal. Inside the coffee shops, along the arcades, to the upper levels of the wealthy residents, and down to the busy bookshops, which these days were permanently packed, this sensational piece of news spread. There were ripples of rumour and panic, and a keenness to know more. As the report of a major happening circulated, many of an estimated six thousand people who were present that afternoon migrated to where the crowd seemed to be concentrating. From a tabletop outside the Café Foy, the charismatic Camille Desmoulins had turned the news into a dazzling speech, a rallying cry to take up arms in protest. While he was in full stride there was a panic that the police were on their way to break up the crowd. He seized on this with a flourish of hyperbole as being ‘the sounding of the tocsin of a new St Bartholomew’s Massacre’. His already keyed-up listeners were agog, hanging on every word. In the course of his oration he picked a leaf from a nearby tree and urged his stunned listeners to follow suit so that collectively they would be displaying the colour of hope. This improvised insignia was a precursor of the tricolour, which shortly afterwards became the approved emblem of patriotism. To emphasize the seriousness of Necker’s loss, Desmoulins urged the crowd to support the proposal of closing the theatres as a sign of mourning. Seizing on this theme, a contingent of the crowd broke away and made for the theatre district in the Boulevard du Temple, leaving in their wake the sorry sight of a tree stripped of any foliage that was within reach, and the ground strewn with broken twigs.

The first Marie knew of the disturbance was when, after invading the Opéra to demand the immediate suspension of the scheduled performance, the crowd surged noisily along the Boulevard du Temple. Chanting ‘Vive Necker! Vive le Duc D’Orléans’, it came to a halt outside the waxworks. Curtius quickly gave instructions for the gates of the railings in front of their house to be shut. But it soon became apparent that the crowd was not as threatening as it looked. Marie describes the protesters as ‘very civil and their general bearing so orderly that she felt no alarm whatever’. At the entrance to the exhibition they entreated Curtius to hand over the wax busts of Necker and the Duc d’Orléans, the people’s favourites–the one whose sacking had strengthened his appeal in their eyes, and the other whose blood-line connection to the King seemed to increase their appreciation of his commitment to their cause. Curtius complied with their requests–not least because he recognized the makings of a sensational publicity coup. Ever the showman, as he handed over the first bust he declared, ‘Necker, my friends, is ever in my heart but if he were indeed there I would cut open my breast to give him to you. I have only his likeness. It is yours.’ There were bows and bravos all round. The ‘what if’ school of historians may be interested in Marie’s assertion in her memoirs that the crowd also demanded the figure of the King, ‘which was refused, M. Curtius observing that it was a whole length, and would fall to pieces if carried about; upon which the mob clapped their hands and said, “Bravo Curtius, bravo!” ’

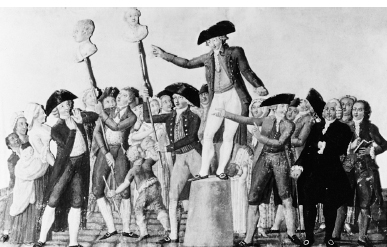

With the heads of their heroes in its hands, the crowd restyled itself as a funeral cortège to show the sorrow caused by the loved minister’s fall, and the mood became more sombre. The heads, elevated on shallow pedestals, were draped with black crape, the material of mourning, and to the beat of muffled drums and with black banners edged in white the cortège processed through the streets. An eyewitness, Beffroy de Reigny, was in the Boulevard du Temple at the time. He put the crowd at ‘five or six thousand’. He reports that they were ‘marching along, quickly and not in any kind of order’, and that they had an improvised selection of weapons and were threatening to burn down any theatres which opened, ‘saying that French people should not be enjoying themselves at such a moment of misfortune’.

Wax heads of Necker and the Duc d’Orléans held high to celebrate the people’s heroes…

…Real heads brandished on pikes to punish the people’s enemies

Through the bustling artisan area of the Rue Denis, and the aristocratic enclave of Rue Saint-Honoré, the procession attracted curious bystanders as it went, and by the time it reached the Place Vendôme there was a considerable multitude of ‘mourners’ rallying around the waxen figureheads. This scene is memorably evoked by Thomas Carlyle:

The Wax-bust of Necker, the Wax-bust of D’Orléans, helpers of France: these, covered with crape, as in funeral procession, or after the manner of suppliants appealing to Heaven, to Earth, and Tartarus itself, a mixed multitude bears off. For a sign! As indeed man, with his singular imaginative faculties, can do little or nothing without signs: thus Turks look to their Prophet’s banner; also Osier Mannikins have been burnt, and Necker’s Portrait has erewhile figured, aloft on its perch.

In this manner marched they, a mixed, continually increasing multitude; armed with axes, staves and miscellanea, grim, many-sounding, through the streets.

As they poured into the Place Louis XV, they came face to face with a company of the Royal Allemand, who refused to salute the busts. Rather like the unfair competition when dogs and donkeys were pitched against bulls at the Combat au Taureau (a popular animal-fight venue near the waxworks), from the outset it was clear the odds were against the civilians, who found themselves face to face with the crack cavalry of the Prince de Lambesc. First insults flew, next stones, and a number of the dragoons panicked and opened fire before charging into the thick of the crowd. A pedlar called François Pepin, described in contemporary records as ‘a hawker of articles of drapery’, was carrying the bust of the Duc d’Orléans. He was shot in the ankle, and received a flesh wound to his chest from the tip of a sabre. He got off lightly compared to the man carrying Necker’s likeness. As the fracas intensified, with fighting spilling over into the Tuileries gardens this unfortunate man was mortally wounded. What Marie referred to as the ‘sanguinary commencement’ of the Revolution had begun, and the waxworks had assumed a crucial place in the historical record. Curtius was later to capitalize on the part his wax artefacts played on this momentous day. In a pamphlet in 1790 he boasted with characteristic aplomb, ‘I can therefore say, to my credit, that the first act of the Revolution happened chez moi.’

While protesters struggled to protect his wax likeness, a short carriage drive away, in the calm of Grace Elliott’s house, the flesh-and-blood Duc d’Orléans was safe and sound. Here, servants in the household informed him that rumours were rife that he had been sent to the Bastille and beheaded. Similar confusion occurs with reports of the fate of the wax busts. Curtius claims that six days after the protest d’Orléans’s head was returned intact. If you reverse the idea of a bull in a china shop, and imagine trying to carry a very breakable object through a stampede, then Pepin’s later testimony suggesting the bust was destroyed in the fracas seems more plausible. This corroborates Marie’s statement in her memoirs that it was never reclaimed, ‘having in all probability been trodden to atoms in the hurry and disorder’. The bust of Necker was returned by a member of the Swiss Guard with singed hair and several sabre wounds to the face, but after careful cosmetic surgery by Curtius it resumed its position in the exhibition. Two days later, in the aftermath of the storming of the Bastille, symbolism gave way to visceral realism when, in full view of a crowd, blunt knives sawed through the necks of real heads, delivering the first bloody totems of mob violence.

For the King, Tuesday 7 July 1789 was a far more eventful day than Tuesday 14 July. On the earlier date his diary entry read, ‘Stag hunt at Port-Royal, killed two.’ On the day the Bastille was stormed it read, ‘Nothing.’ While the King’s hunting log showed that he had a disappointing day, Curtius by contrast was in the thick of the action. He had been recruited as a district captain in the newly created National Guard, an instant people’s army formed in a matter of days as a response to the escalation of public disorder. He took to his new role with gusto, and claimed that on his first day of active service his intervention had prevented a gang of ruffians from burning down the Opéra and other theatres in the boulevard: ‘Their torches were all prepared, and without my vigilance they would have destroyed one of the finest quarters of Paris.’ The success of the stand-off between his troop of forty and the six hundred incendiaries he put down to his personal diplomacy: ‘I went out at the head of my troop and spoke to them. By good luck I convinced them. They gave up their wicked ideas and made off.’

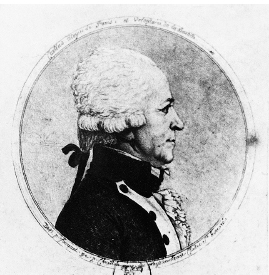

Curtius in National Guard uniform

As the call went up to procure arms for the new civil militia, Curtius joined the search for weapons. Far from demanding the latest military technology, they even resorted to raiding the museum in the Place Louis XV for any crossbow or sword that might be put into service regardless of its status as historical relic. At the Hôtel des Invalides they raided a considerable cache of muskets. But guns without powder were useless. What the motley militia who made their way to the Bastille had in their sights was the vast quantity of gunpowder that the Swiss Guards had recently stored there, supposedly out of harm’s way.

Curtius made much of his role as a vainqueur de la Bastille, the title conferred on the band of patriots (whose numbers have been put at between 800 and 900) who made their way to the legendary medieval fortress in pursuit of gunpowder. He used the title in all his correspondence, displayed the commemorative engraved gun that each vainqueur was given later, and in 1790 published a pamphlet entitled Services du sieur Curtius, vainqueur de la Bastille. This boastful account reads as if the falling of the Bastille was his personal triumph. As in so many of the testimonies about the event, Curtius exaggerates liberation and downplays the objective of seizing gunpowder. He reinforces the potent symbolism of the ancient medieval fortress as the concrete expression of despotism, which in turn has the effect of dramatizing the significance of its fall. He describes with pride his part in ‘the final dangers and glory of a conquest that put a seal on our liberty’.

In reality what happened was anticlimactic. In the first place the Bastille could have swung a sign saying ‘Vacancies’: there were only seven prisoners. In people’s minds it was an impenetrable warren of dungeons and torture chambers, where each cell was a hell of rats and chains in which curling fingernails scratched last words on mouldy walls so thick they muffled even the loudest screams. Incarceration there symbolized a slow, dark death–like being buried alive. In reality it was far less inhospitable. Prisoners could pay for upgrades, and were allowed home furnishings such as fire tongs. In fact room service was so good that one aristocrat described how surprised he was when, after finishing his unexceptional first meal there, a much better one arrived moments later, and he realized he had eaten that intended for his visiting valet. Testimonies by former prisoners feature unlikely references to creature comforts, notably the Bastille’s house blend of coffee, which was evidently ‘the best Mokka’. Unlike the man-in-the-iron-mask folklore, prisoners were not in chains but, as in some twenty-first-century hotels, were encouraged to make use of the exercise area on the roof with its panoramic views of the city.

As for the prisoners, they were no longer the calibre of the popular heroes of the past, innocent victims of a whim of a king who only had to put a name on a lettre de cachet for a lock to be turned and a life to be clanked shut. At the time that Curtius was rallying his men outside the prison gates, the inmates were hardly a magnificent seven. They comprised four forgers, the incestuous Comte de Solages, whose own family wanted him locked up to protect them from him, a deranged Englishman, and an Irish debtor whom Marie identifies in her memoirs as the extravagantly named ‘Clotworthy Skeffington Lord Masareen’ and who, she states, ‘was not confined in the cells but had an apartment on the first floor’. A week earlier an even bigger public-relations headache for the liberation cause would have been the Marquis de Sade, but he had just been transferred to Charenton. In fact, though this was not common knowledge in July 1789, as part of a general programme to modernize the medieval remnants of Paris the Royal Academy of Architecture already had the Bastille in their sights for demolition. Regarding it as a large dark blot on the urban landscape, in its place they had in mind a colonnaded atrium with a fountain–a light, bright civic oasis of calm. The design for a space with no specific function was rather appropriate to replace a building that had ceased to fulfil its original purpose and was largely redundant, a pre-Enlightenment throwback to darker forms of despotism when kings were cruel. In July 1789 it was what lay on the outside of its walls that was foreboding, as the impregnable fortress was faced with the challenge of keeping people out.

As sieges go, the storming of the Bastille lacks the requisite duration to be one of the great ones. It was over in hours rather than days, and the really big guns that were the cannon on the ramparts were never fired. In terms of blood and thunder it was more whimper than bang. It even started with an invitation by the anxious governor to the leading assailants to join him for what turned out to be a long and inconclusive lunch. It was clear that by temperament poor Bernard-René de Launay was more a white-handkerchief-waver than a nerves-of-steel hero. But the short route to the assailant’s victory via weak resistance, capitulation and surrender was not without casualties on both sides. By the time the vainqueurs finally got their hands on the barrels of gunpowder, with the almost incidental outcome of the release of the ragtag inmates, their casualties stood at eighty-three, compared to a single victim from the Bastille defence. De Launay’s murder shortly afterwards was a brutal addition to this tally. A young journalist, Loustallot, reported the event in the first issue of Les Révolutions de Paris, one of a spate of new newspapers that appeared at this time: ‘De Launay was pierced by countless blows, his head was cut off and carried on the end of a spear, and his blood ran everywhere.’ The provost Monsieur de Flesselles met a similar fate, and impaled on pikes the heads were paraded through the streets. In grizzly imitation, true copycat style, only days later the children of Paris started to play ‘let’s pretend’ by impaling real cats’ heads on sticks and staging their own parades.

The fall of the Bastille became epic retrospectively, significant more for the meaning it was given afterwards than for what happened at the time. At the forefront of those shaping interpretations for their own ends were Curtius and Marie. Certainly the acquisition of gunpowder was crucial for a people’s army which, only hours before, had had muskets but no ammunition. And this material empowerment was another milestone for the Third Estate, which only months ago had been without electoral representation. The storming of the Bastille served as a brilliant symbol for the transformation of subjects into citizens. It represented the birth of patriotic propaganda–and it was not just politicians who seized the opportunities to capitalize on this.

In the spring of 1789, as bread costs severely stretched domestic budgets, Curtius and Marie had for the first time felt the knock-on effects. Takings dipped and attendance fell away, as even the few sous necessary for a little light relief could not be spared. Cash flow was of sufficient concern to prompt Curtius to start what would be a protracted correspondence to chase a further inheritance claim on his maternal uncle’s estate in Mayence, Germany. Legal letters dating from early April show that he had already received a legacy, but was pursuing that of his elder brother Charles, who was also a beneficiary but had been missing for some years. In July, however, the storming of the Bastille meant that prospects were suddenly looking brighter, as the Revolution played into the hands of the commercial entertainers and a wide range of entrepreneurs.

Curtius quickly realized that the events racking France had the potential for malleability, like the wax that was his medium. They could be fashioned in any number of ways to accommodate different markets. In London, in September 1789, the star billing in advertisements for Philip Astley’s circus at the Royal Grove, Westminster Bridge, was as follows: ‘Finely executed in wax by a celebrated artist in Paris, the heads of Monsieur de Launay, late Governor of the Bastille, and M. de Flesselles, prevôt de marchands (sic) of Paris with incontestable proofs of their being striking likenesses’. The show promised to exhibit the heads ‘in the same manner as they were by the Bourgoisie [sic] and French guards’. Elsewhere it was stressed that these facsimiles had been ‘obtained at great expense’. They proved so popular that later advertisements boasted, ‘The head of the Governor which Astley has brought from Paris is so finely modelled that almost every artist in London is anxious to take a drawing, for which purpose several of them have been attempting to take sketches as we suppose for magazines, print shops etc.’ Evidently Curtius had cottoned on to the role that replica heads could play as valuable visual dispatches from abroad. Marie makes no mention of these heads in her memoirs, and it seems more likely that they were the work of Curtius himself, whose medical background and earlier experience making anatomically correct replicas would have served him well in the manufacture of macabre relics.

Nine days after the fall of the Bastille, the murder of Curtius and Marie’s neighbour Foulon became their next grizzly subject. Révolutions de Paris reported this beheading with relish: the ‘severed head separated far from his body was carried at the end of a pike through all the streets of Paris…His body that was dragged through the mud and carried all over the place announced the terrible vengeance of a people rightly angry towards tyrants!’ The unfortunate Foulon, a former finance minister, had made an ill-judged remark about food shortages, flippantly suggesting that people eat hay. Marie describes how, by way of revenge, a furious mob tracked him down at his country house and forced him back to the city, where he was subjected to a humiliating parade through the streets. Shamed and cheered with a collar of nettles round his neck, a bunch of thistles in his hand and a truss of hay tied at his back, he was finally dragged to the Hôtel de Ville and hanged. After death his head was hacked off and impaled on a pike cruelly brandished in front of his distraught son-in-law Berthier de Sauvigny, before he too was beheaded. Both heads were paraded on pikes, Foulon’s gaping mouth mockingly stuffed with straw and dung. Other accounts of this well-documented double murder highlight the matter-of-fact tone of Marie’s own recollection of it. She recalls the actions of the mob with no hint of her own feelings about either their barbarity or her having witnessed the murder of a neighbour. There is no trace of revulsion. Even making allowances for the distance from which she recalled events in her memoirs, her impersonal tone is striking. In an understatement which contrasts sharply with other witnesses, she confines herself to the opinion, ‘This event was a dreadful shock to all who wished well to their country, as it proved that the mob were too strong for the constitutional authorities.’

From locks to bed-linen there was a vast range of Bastille-themed merchandise

Grace Elliott, for example, was a less cool witness to the atrocity. Much of her memoir of the French Revolution reads as an innocently unselfconscious revelation from a privileged perspective. It is the Revolution seen from inside a carriage on the way back from the horse races at Vincennes, or from a private box at the theatre. It is revolution as inconvenience, traffic jam and interruption. Thus Foulon’s beheading stops her shopping. She is en route to her jeweller’s in the Rue Saint-Honoré when she encounters ‘a procession of French guards carrying Monsieur Foulon’s head by the light of flambeaux. They thrust the head in my carriage and at the horrid sight I screamed and fainted away.’ In his memoirs Chateaubriand describes graphically ‘the horrid sight’ that caused Grace Elliott to pass out. In the street outside his aristocratic mansion he had a chilling encounter with Foulon’s killers, who ‘were singing, capering, leaping to bring the pallid heads nearer to my own head. An eye in one head had been pushed from its socket and was dangling on the corpse’s face, the pike sticking through the gaping mouth, the teeth clenched on the iron.’ The visceral reality of Foulon’s mangled body makes Marie’s coolness seem even more striking.

Importantly, Chateaubriand’s testimony suggests it might be right to challenge the widely held belief that casts were always made from the actual human remains. For maximum impact the wax heads needed to be easily identified–an unrecognizable mush would have no value. For a practised modeller, copying rather than casting from death seems a much more plausible method. Casting from the bloodstained original, while it became an important tool in Marie’s marketing initiative later on, was not necessary in order to reproduce a convincingly ghoulish image. The head of Foulon was particularly popular, and promotional material for the exhibition made much of the fact that ‘the blood seems to be streaming from it and running on the ground’. Whereas Curtius and Marie had established their reputation with the allure of glamour, the new market centred on gore, and the voyeuristic lure of the brutalized body–but sufficiently sanitized to appeal as an exhibit that people would pay to see. They controlled sensation rather as the media today edit and airbrush the atrocity pictures that come into the public domain.

Lurid souvenirs of the bloodshed were but one facet of the new souvenir industry that emerged with the fall of the Bastille. There was a vast range of commemorative merchandise. From Bastille bonnets trimmed with fabric towers to Bastille shoe buckles, there were head-to-toe choices. There was even Bastille bed linen, with siege motifs that one would not have thought conducive to aristocrats getting a good night’s sleep. And there were also Bastille panoramas, peep shows and plays. In fact there was no escape from the Bastille as a money-spinning theme. Long before its fall, this prison had exerted a great fascination for the public, with former prisoners turning their experiences into best-selling books. Simon Linguet’s account of his two-year imprisonment was one of the most popular prison memoirs. First published in 1783, it reinforced the terror the place inspired, and its immense success meant that Linguet had the accolade of being featured in Curtius and Marie’s collection. He kept alive preconceptions about the prison that made the public highly receptive to the versions of its fall that were sold in such a compelling variety of forms in July 1789.

The contract for its demolition won by the builder and stone-mason Pierre-François Palloy was a significant commercial coup. It is no surprise to learn that this self-styled ‘Entrepreneur de la démolition de la Bastille’ was a good friend of Curtius. Like him, he exploited every commercial opportunity with panache. Under his guidance the Bastille was broken up and remade into an immense amount of imaginative merchandise. No stone was left unturned. Stone fragments became patriotic front-door steps; they were etched with maps, inscribed with words, and incorporated into mass-produced presentation packs, which also featured a seemingly endless supply of authentic keys. They were carved into busts of Mirabeau, and crafted into jewellery for all budgets. Poorer patriots displayed small chips in rings, but Madame de Genlis probably had difficulty standing upright, such was the size of her Bastille bling. A large highly polished fragment was studded with the word ‘Liberté’, spelled in gems, and surrounded by tricolour motifs in rubies, sapphires and diamonds, all entwined with laurels. And relics were also the basis of a ‘Liberty’ museum which, after exhausting Parisian interest, Palloy sent on tour all over the country, like a portable theme park.

Macabre memorabilia also sold well. Metal fixtures and fittings were melted down and marketed as inkwells made from leg-irons, medallions from manacles. Commercial opportunism extended even to England, where, with an eye to the export market, designers responded rapidly to the dramatic turn of events in France. It was not just Marie and Curtius who profited from heads. The Wedgwood brothers announced, ‘We are making Mr Necker’s head of a size proper for snuffbox tops.’ Elsewhere, the Duc d’Orléans’s head was shrunk to fit on to gilt buttons, and both the people’s heroes featured on a range of plaques and in endless plaster busts. Adaptability was the key requirement and, eager not to miss their moment with their range of Bastille medals, the Wedgwoods took artistic licence, merely modifying figures they had used the year before to commemorate the American wars of independence. The jasperware medallion advertised as showing the goddess of Liberty holding hands with France was in fact an ingenious bit of recycling, as evidenced in a letter by Josiah Wedgwood dated 29 July: ‘The figure of Hope in the Botany Bay medal would come in exceedingly well for the figure of Liberty.’

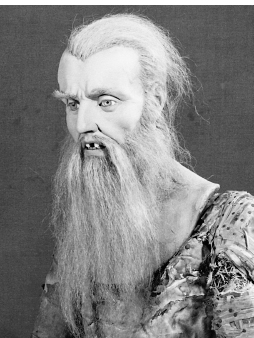

The public readily subscribed to the idea that in celebrating the storming of the Bastille they were celebrating the symbolic defeat of despotism. Newspapers fed them this angle: as one report put it, ‘The dungeons are opened; liberty is given to innocent men, and to venerable old men surprised to see the light. For the first time, august and sacred liberty finally entered this abode of horrors, this dreadful asylum for despotism, monsters and crimes.’ A barrage of products reinforced the liberation-propaganda bandwagon. But the most audacious piece of propaganda can be attributed to Marie–the full-length wax figure named as the Comte de Lorges. The Wedgwoods’ artistic licence with their Liberty medal pales compared to Marie’s with this composition, which is one of her most famous works. The figure of a wild-eyed, toothless old man with a long white beard is the perfect realization of the mental images that haunted the popular imagination about the victims of the Ancien Régime, incarcerated in dark dungeons called oubliettes, and forgotten by the outside world. The wax representation of the Comte is the fictional compensation for the factual deficiencies of the sorry cast of inmates who were released by the vainqueurs. Given that none of the prisoners was the raw material to inspire public sympathy, a journalist–Carra–did what journalists still do: he abstracted from the facts a human-interest story that would engage. Published in September 1789, and entitled Le Comte de Lorges prisonnier à la Bastille pendant 32 years enfermé en 1757 et mis en liberté 14 July 1789, the slim volume was an instant success. This was the blueprint for Marie’s reconstruction, the word made wax. Her figure, later seen by Charles Dickens in mid-nineteenth-century London, seems to have percolated in the novelist’s imagination until being reborn as Dr Manette in A Tale of Two Cities (1859). The long beard and unkempt appearance which emphasize the impact of Manette’s long-term isolation in cruel captivity echo very clearly de Lorges.

Marie is emphatic about de Lorges. She makes no mention of her part in the wax likenesses of the first victims of the Revolution, but de Lorges is the first figure since the outbreak of the Revolution for which she takes full credit. She describes how the Comte was discovered with other prisoners in dark dungeons beneath the prison. The ‘most remarkable’ among them, she says, ‘he was brought to her that she might take a cast from his face, which she completed. It is a whole-length resemblance taken from life. He had been thirty years in the Bastille and when liberated from it, having lost all relish for the world, requested to be reconducted to his prison and died a few weeks after his emancipation.’ Her earliest posters advertising the exhibition when she came to England also made reference to him, and in catalogues she even tackled those sceptical about the true history of this frail old man by reasserting her personal acquaintance: ‘Existence of this unfortunate man in the Bastille has by some been doubted, but Madame Tussaud is herself a witness of his being taken out of that prison July 14, 1789.’ There is more than a hint of Manette in her catalogue description of how ‘the poor man unused to Liberty for 30 years seemed to be in a new world’ and ‘frequently with tears he would beg to be restored to his dungeon.’ The figure was often singled out for praise in reviews of the exhibition: in Liverpool, for example, the edition of the local paper for 14 April 1821 declared, ‘The Count de Lorges is a fine piece of physiognomy.’

Marie’s wax model of the Comte de Lorges

To give further veracity to her account of the liberation of the Comte de Lorges, Marie’s memoirs invoke Robespierre. Before Palloy’s demolition squad reduced it to rubble, the deserted prison became the prime destination for curious sightseers, including Marie. She describes how Robespierre, like a tour guide, conducted the fascinated visitors to the different parts of the prison–including the cell where de Lorges had been confined. Here he burst forth into an energetic declamation against kings, exclaiming, ‘Let us for a while reflect on the wretched sufferer who has been just delivered from a living entombment, a miserable victim to the caprice of royalty.’ Her account of her visit is also memorable for her claim that, descending the narrow stairs, she slipped and ‘was saved by Robespierre, who catching hold of her, just prevented her from coming to the ground; in the language of compliment observing that it would have been a great pity that so young and pretty a patriot should have broken her neck in such a horrid place’. In a life notable for a preponderance of twists of fate, how ironic that Marie nearly met her own death while visiting the dungeon that later on indirectly contributed to her financial fortune–if indeed she was not simply creating a frisson for her English audience by this account of a notorious murderer saving her neck in such a poignant place.

What is incontrovertible is the widespread credence given to the myths and misleading interpretations of the physical remains of the Bastille. Such was the gullibility of the public that an old printing press was presented to them as a despicable instrument of torture, and human remains from the medieval past unearthed during demolition were given new biographies to better fit the status of recent victims of barbaric kings. Across the board the public subscribed to the symbolism. The son of an English doctor recording his impressions as a sightseer spoke of ‘the fallen fortress of the tyrannic power’, and in a similar vein Madame de Genlis referred to ‘the frightful monument of despotism’. Marie helped propagate this perception. Dungeons had been full of noxious vapours and stench; cells infested ‘by rats, lizards, toads and other loathsome reptiles’; airless windowless cells admitted neither light nor fresh air; torture instruments would punish ‘those unhappy persons whom the cruelty or jealousy of despotism had determined to destroy’. And, most chilling, there had been ‘an iron cage about twelve tons in weight with a skeleton of a man in it who had probably lingered out a great part of his days in that horrid situation’. To read her account of her purportedly first-hand experience in the Bastille is to see a blueprint for the synthetic dungeon that eventually became known as the Chamber of Horrors. Two models of the Bastille, one showing it before the fall, and the other in ruins, were also put on display in the Boulevard du Temple exhibition, and later came to England with her. But Curtius’s show-stopper in the summer of 1789 was a tableau of the siege–a theatrical backdrop to the unambiguously authentic heads of de Launay, Flesselles and Foulon. The collection, formerly a frivolous and fashionable recreation, was fast becoming an indicator of the political climate.