6

Model Citizens

WHILE CURTIUS AND Marie adapted their exhibition, a wave of idealism swelled. In 1790 the anniversary of the storming of the Bastille saw the first epic Revolutionary festival for a mass audience. Choreographed by the painter Jacques-Louis David, it took place on the Champ de Mars, rather than the site of the Bastille, and was designed to emphasize unity and to usher in a new era of classless harmony. Where formerly privilege and tradition had divided, patriotism was presented as a unifying force. In the spirit of equality, a cast of thousands were not just spectators but took a participatory role in the preparations, including site preparation and setting up the enormous amphitheatre and stage. Marie describes taking part in this communal earth-shifting, when both the highest and the lowest wielded the spade and the pick in fraternal harmony, and she herself trundled a barrow in the Champ de Mars. A fellow wheelbarrow-pusher and witness was Madame de La Tour du Pin, who noted, ‘Laundresses and Knights of St Louis worked side by side.’

Whereas Ancien Régime pageantry was a spectacle of power, reinforced by the sheer force of time and tradition, this revolutionary display was an ephemeral celebration of the present. David conceived everything on a spectacular scale, with dazzling special effects designed to increase the visual impact. Variously featuring in his festivals were fountains gushing from gigantic breasts, processions of children, clouds of white doves, the burning of old symbols, the brandishing of banners bearing new ones, togas and chariots, laurels and cypress, classical imagery recast for a new civic idyll. He also had a mass-choir habit. But it was eventually to become apparent that the new political landscape he was dramatizing was as flimsy and unstable as his plaster-of-Paris models and cardboard mountains. Unity and fraternity were not achieved simply by putting on a spectacular show of these virtues. Festivals alone did not instantly inculcate their values in the hundreds of thousands of citizens who saw them, and the hope that patriotism would prove a cohesive force proved to be wildly over-optimistic. The initial sense of l’année heureuse quickly gave way to an overwhelming feeling of anticlimax. Equality too was to prove elusive in practice. The festival generated a huge influx of custom from beyond the city for the prostitutes in the Palais-Royal and yet, far from displaying a spirit of unity and equality, the opportunist girls had no qualms about charging young clients six livres, and more mature clients twelve.

As people embraced a patriotism that theoretically dissolved class differences, there was a backlash against the former frivolities of fashion. As well as pushing together to make a public arena, people in a new way pulled together to swell the national coffers. There was a mass meltdown of shoe buckles and silver accessories, as citizens from all classes proffered their valuables to the mint. The zest for patriotic donations and the eagerness to have one’s name printed on the thanksgiving lists of the National Assembly meant that patriotism itself became a fashion, and its dictates were taken every bit as seriously as the wildest extravagances that had been so blindly adhered to before. Hairdressers adapted by promoting patriotic hairstyles. In place of wigs and powder, the look was overtly low maintenance, the implication being that, whereas aristocrats devoted hours and fortunes to their high hair, the patriotic mind was on a higher plane. Marie records the changes: ‘the hair cut short without powder “à la Titus” and shoes tied with strings’, where before ‘hair was worn long and powdered and buckles were in use for the shoes.’ The new look did not impress the English aristocrat William Wellesley-Pole: ‘Men in order to show their democracy have sacrificed their curls and toupees; some of them go about with cropped locks like English farmers without any powder, and others wear little black wigs.’

However, if the former excesses were curbed, they were not completely quashed. Enterprising jewellers produced glass and crystal trinkets emblazoned with slogans such as ‘La Patrie’. Brass shoe buckles were marketed as ‘à la nation’ and even milliners cottoned on to this ruse, merely renaming their confections in tune with the times. Writing from Paris to his wife in the country, the Marquis de Mesmon tells her he has bought her a ‘terribly pretty hat in the latest fashion which is entitled “To Liberty”–the most ravissant dernier cri!’ What all this meant for Curtius and Marie was packing away all the frills and finery, and consigning their Bertin creations to dust sheets and trunks, as increasingly they found themselves kitting out their figures in uniforms.

The kaleidoscopic fashion palette of the Ancien Régime dried up to three colours: red, white and blue. Florists did well with poppies, daisies and cornflowers, and ribbon-makers profited from a run on tricolour trimmings, which were worn in buttonholes, and as rosettes and cockades. Finery with aristocratic associations was out, and, for those who had depended on the ostentatious consumption associated with feudalism, patriotism was a disaster. ‘The embroiderers are going bankrupt; the fashion merchants are closing down; the dressmakers are sacking three-quarters of their workers. Women of quality will soon no longer have chambermaids.’ Not generally known for his fashion tips, Marat’s fashion forecast was bleak. ‘I should not be surprised if in twenty years’ time there is not a single worker in Paris who can trim a hat, or make a pair of pumps.’

In contrast, the rag-sellers and ink suppliers and those engaged in papermaking, printing and publishing all flourished. The official records of the new governing bodies and the public appetite for news generated a vast market for paper and print, and with the quickened pace of current affairs journalists thrived as never before. The wax-works were in a unique position to give a visual commentary on the changes. They were able to keep abreast of every development, where other manufacturers struggled to keep up. Topicality was particularly problematic for the producers of politically themed objects. For example, designs for plates with images and slogans for one political phase became quickly obsolete, given the turnover of governing bodies, each with a different agenda. The waxworks, however, were ideally placed to cater to a climate of instability. A nineteenth-century commentator, Audiffret, gives a good summary of Curtius’s adaptability. ‘Curtius made a display of his patriotism from the start of the Revolution; he offered for the public approval or execration the men of the hour or the whirl of fashion, victors and vanquished, and awarded them a place of honour or infamy according to the circumstances. He became a weathercock, like so many men who did not boast about it and who had found for themselves a way of making money.’

The weathercock response was not only a sound commercial strategy: it was to become a means of survival. Ill winds were gusting in 1791. The death of Mirabeau–who, in spite of his aristocratic status, had played a prominent part in the first phase of the Revolution and been elected to the Estates General as a representative of the Third Estate–was crushing for the moderate cause. Marie describes his funeral cortège as exceeding anything of the kind she had ever witnessed. His funeral was also significant as the inauguration of the Panthéon as a secular hall of fame for the great and the good. The architect de Quincy extended Soufflot’s supremely elegant neoclassical shell of the unfinished church of Saint-Geneviève into a space that signified the symbolic and secular reorientation of social values. The Panthéon was radical in recognizing worth and birth as separate and unrelated criteria for social distinction. In a new way, worth was in the eye of the beholder, and the people, not the Establishment, were ostensibly the arbiters of greatness. As Madame de Staël noted, ‘For the first time in France a man celebrated by his writings and his eloquence received honours formerly accorded to great noblemen and warriors.’ However, although the Panthéon might have looked more democratic, in a sense it was much less so than a Christian church. At a crucial doctrinal level, whatever the trappings of social hierarchy, all souls were equal before God. Kings and peasants alike knew they would be judged by the same God. In the Panthéon, some people were explicitly more ‘worthy’ than others, and the entity ascribing worth was the nation/state/Revolutionary government. What mattered was the ‘will of the people’–though all too often this turned out to be the whim of some politician. Nevertheless, the Panthéon replicated on a grand scale what the waxworks provided as a popular entertainment, a forum for secular idolatry.

In his diary, Gouverneur Morris, reflecting on Mirabeau’s funeral, eloquently conveys the climate of changeability, and questions the honours accorded to the first resident of the Panthéon: ‘I have seen this man, in the short space of two years, hissed, honoured, hated and mourned. Enthusiasm has just now presented him gigantic. Time and reflection will shrink that stature. The busy idleness of the hour must find some other Object to execrate or exalt. Such is Man, and particularly the French Man.’ This was to prove true, and when Mirabeau’s double-dealing with the royal family was later uncovered, his mortal remains were ignominiously removed from the Panthéon. The installation and subsequent removal of Mirabeau was a grand-scale version of the simple dynamics of the chop-and-change celebrity culture promoted so successfully by Curtius and Marie. Like contemporary celebrity culture, political allegiance to specific people was eternal only while it lasted, an unstable mix of sincerity and fickleness. The waxworks were at the apex of the culture of impermanence, charting the changing allegiances in public life.

The fact that Curtius was politically active, with a role in the National Guard and a member of the Jacobin Club, meant that it fell to Marie to keep the exhibition running smoothly from day to day. As a captain in the newly co-ordinated civic militia called the Chasseurs, Curtius was required to go on anti-smuggling patrols and to supervise food distribution. All this ate into his career as a showman, and in his pamphlet he referred rather resentfully to ‘sacrificing the time belonging to my work. This is a loss for an artist.’ Although the proliferation of men in uniform on the streets was a reminder of the background tensions, there was an atmosphere of relative calm until the King’s abortive flight in the spring of 1791. After this the divisions between royalists and republicans became more serious. Marie notes in her memoirs, ‘France was at this period rent by different factions.’

There was an all-pervasive sense of duality, and of people at all levels of society being challenged by conflicting allegiances and divided loyalties–Curtius the artist-businessman negotiating an incredibly politicized environment and torn between show business and civic duties; the members of the French Guard increasingly torn between loyalty to the King and empathy with the National Guard; the general public split between moderate Girondins and extreme Jacobins; the National Assembly pulled between appeasing the people and punishing the King; and the King himself torn between complying with the constitution and fleeing to reassert his power, assisted by foreign allies. In this climate, allegiance started to become a much more serious matter, and one can begin to understand the origins of Marie’s reticence. Her iron will seems to have been forged in these trying times when it was at first prudent and then became vital that she learned not to say how she felt, not to tell what she knew. An extra pressure was that the exhibition was a highly conspicuous public arena, with the stakes set high if the tableaux and figures did not chime perfectly with public opinion.

With the failed escape attempt of the royal family, all vestiges of respect for monarchy vanished. As Grace Elliott noted, ‘Even those who some months before would have lain in dust to make a footstool for the Queen passed her and splashed her all over.’ There was even more contempt for the King. He was called Louis the Hated and Louis the Fat Pig–Marie certainly blamed the failure of his escape attempt on the legendary Bourbon greed, given that he had insisted on stopping for supper. At the family home she eavesdropped as political talk at the dinner table turned to republicanism:

Many members of the Jacobins who began about this period to frequent the house of M. Curtius would speak boldly as to the formation of a republic, and the destruction of royalty; and soon the cry of ‘No King!’ was heard throughout the streets, and was even disseminated through the medium of the public papers, whilst the clubs of the Jacobins and Cordeliers, ever the most furious and daring, echoed the yell of ‘Down with the Monarchy’ in all their meetings.

Writing on the eve of the Revolution, Mercier had challenged France to remould itself. In a stirring address, he had urged his audience to grasp the potential for change: ‘See that you are ruled not by order of nature but by caprices, which your cowardice has allowed to harden into laws. Know yourselves, hate yourselves and in that excellent discontent remould your world!’ By 1791 discontent had turned into belief not just that the monarchy should be brought to heel, but that it could be removed. Remoulding was dramatically under way–most especially in the waxworks, where Marie found herself working all hours on an ever-shortening cycle of removals and renewals.

Beyond the waxworks, the quest for change involved the destruction of material objects, such as the burning of aristocratic pews in churchyards, the painting over of all aristocratic livery and the felling of royal statues by way of a ritual purging of feudal symbols. But rapidly the focus shifted to flesh-and-blood subjects. If in 1790 the number-one hit and national theme song was the optimistic ‘Ça Ira’–a pre-Revolutionary version of ‘Que Sera Sera’: ‘Things will work out’–then by 1791 a new second line was ominously violent: ‘Let’s hang aristocrats from the lanterns!’ This was belted out with gusto at every opportunity. Similarly violent was the oratory of Danton and Marat, who supplied a significant amount of the raw material from which the social order was being recast. Marie lets us see them afresh. Danton’s mild manners off the podium were greatly at odds with his formidable physical presence–‘His exterior was almost enough to scare a child; his features were large and harsh…his head immense.’ Marat, in stark contrast, was ‘short with very small arms, one which was feeble from some natural defect, and he appeared lame; his complexion was sallow, of a greenish hue, his hair was wild, and raven black; his countenance had a fierce aspect.’ She describes his fire-in-the-belly speeches as seeming to come from someone under the influence of some ‘demonical possession’.

She had ample opportunity to formulate her impressions of Marat, because on one of the many occasions when his newspaper L’Ami du peuple incurred the enmity of the authorities he sought asylum at her home. She relates how he arrived with a carpet bag and stayed for a week. He appears to have been an undemanding house guest, spending most of the time writing–‘almost the whole day in a corner with a small lamp’. On one occasion he subjected her to a private hearing of his political rhetoric, tapping her on the shoulder ‘with such roughness as caused her to shudder, saying, “There, Mademoiselle, it is not for ourselves that I and my fellow labourers are working, but it is for you, and your children, and your children’s children. As to ourselves we shall in all probability not live to see the fruits of our exertions”; adding that “all the aristocrats must be killed.” ’ She then describes a chilling postscript to her conversation with him when Marat ‘made a calculation of how many people could be killed in one day, and decided that the number might amount to 260,000 [sic]’. She described his newspaper as ‘one of the most furious, abusive and calumnious productions which ever appeared, its object being to inflame the minds of the people against the King and his family, and in fact to incite them to revolt and to the destruction of every institution and individual likely to afford support to the tottering monarchy’.

The silence of what Marie omits from these recollections of her fanatical guests, namely the personal feelings they evoked in her, is deafening. Given her supposed eight-year tenure as royal art tutor at the palace of Versailles, and the strong bonds of reciprocal friendship she professed between herself and Madame Elizabeth, she seems to have shown great restraint in withholding any royalist sympathy in the face of Marat’s republican rants. Interpretation of her reticence depends on how much credence one gives to the story of her life presented in the memoirs. In the eye of the Revolutionary storm her fence-sitting is the sign not of an unfeeling person, but of a prudent person; restraint at that time would have been understandable. But far away from the dangerous atmosphere of Revolutionary Paris, when recollecting events so many years later, her reticence is baffling. Rather as moths adapt their wing colour as a survival camouflage, perhaps Marie’s apparent thick skin was developed as a survival mechanism in dangerous times. Decisions about the content of the exhibition were becoming fraught. Curtius’s aristocratic connections were what propelled him into the Parisian limelight in the first place, and Marie made much of her links to the court circle. One surmises that she would have been torn between preserving the haut ton of the exhibitions with royals and courtiers, and focusing more on the new wave of activists and agitators. If Curtius was more naturally disposed to the latter course, and jumped on every passing bandwagon, then Marie’s strategy was to cultivate the impression of being an innocent victim of circumstances, a reluctant collaborator. (In England she always defended Curtius’s reputation, and claimed he too had been a royalist compromised by circumstances. The London Saturday Journal in 1839 reiterated the claims in the memoirs: ‘Her uncle always persisted in saying, however, even after he had fairly joined the revolutionists, that he was a royalist at heart, and that he had only favoured these visionaries, and entered into their views, to save his family from ruin.’)

An important element in the realignment of social values and the secularization of France at this time was the energy that went into demoting the power of tradition by devising new rituals. David played a major role in masterminding the aesthetic of the Revolution, and according to Marie he was an associate of Curtius and a familiar face at the family home. In what appears as a consistent theme of her own magnetic attraction for powerful men–remember the King’s brother tried to kiss her, Voltaire complimented her on her looks, Robespierre called her a pretty patriot–David was always very good-natured towards her, but his originality clearly deserted him in using the old cliché of ‘always pressing her to come and see his paintings’. It was an unreciprocated admiration: she calls him a monster, and ‘most repulsive’. ‘He had a large wen on one side of his face, which contributed to render his mouth crooked; his manners were quite of the rough republican description, certainly rather disagreeable than otherwise.’ David was evidently acutely self-conscious about ‘the revolting nature of his countenance, manifesting the utmost unwillingness to have his likeness taken.’ However, Marie evidently persuaded him and although the likeness did not come with her to England, she states that she produced ‘a most accurate resemblance of that eminent artist’.

Whatever Marie’s personal relationship with David, he incorporated a wax figure of Voltaire in the festival dedicated to the writer in July 1791. This was the second time that wax figures from the exhibition had played an integral role on the wider stage of the Revolution, but the earlier impromptu use of two busts in July 1789 was very different from the carefully choreographed role that the figure of Voltaire played on this occasion–aboard a magnificent chariot and clad in vermilion robes. It was the centrepiece of a cast-of-thousands production devised by David for the writer’s grand entry into the Panthéon. In his diary, Lord Palmerston referred to ‘a figure of Voltaire very like him in a gown’ and ‘a very fine triumphal car drawn by twelve beautiful grey horses, four abreast’. Unfortunately, torrential rain made the colours of the robes bleed, but it was Curtius who had a red face when VIPs roundly blamed him for failing to do justice to the event with the rain-streaked figure. The press, however, were more interested in contrasting Voltaire’s glory with the mocking of the King. Engravers had a field day juxtaposing Voltaire being crowned and fêted with adulatory fanfares with the King being insulted by fanfares of farts from the behinds of angels.

Only days after the Panthéonization of Voltaire, a republican rally in the Champ de Mars was quashed by force when Lafayette fired on the crowd. But the zeal of the republican cause was by now bullet-proof, and the dethronement of the King was now not likely but inevitable. Shortly after this, a brave public-relations exercise on the part of the royal family backfired horribly when the Queen, her children and Madame Elizabeth went to the Comédie-Italienne. Incensed by the leading lady, Madame Dugazon, seeming to address one aria directly to the Queen, when she sang the line ‘Ah, how I love my mistress!’, the Jacobins in the stalls could not contain themselves. Grace Elliott relates how ‘some Jacobins who had come into the playhouse leapt upon the stage, and if the actors had not hid Madame Dugazon, they would have murdered her. They hurried the poor Queen and her family out of the house, and it was all the Guards could do to get them safe into their carriages.’ This was the last public appearance of the Queen before that engagement that she did not plan and where she would find herself centre stage, drawing the gaze of a vast audience as drums rolled.

From the invasion of a stage and upstaging of a public performance by a few angry Jacobins, in 1792 the boundaries that were breached became more serious. The lines crossed were to involve nations and frontiers, and most dramatically the invasion of the royal family’s private quarters in the Tuileries with devastating consequences. On 20 April 1792, when France declared war on Prussia and Austria, there was a sense that what had started as a popular uprising, which it was thought could be contained and directed by new authorities, was becoming increasingly unmanageable. Marie, by now a woman of thirty-one, began to live at the centre of a city where the difficulties of day-to-day life were exacerbated by war. ‘La patrie en danger’ heightened nationalistic fervour. Whereas the outbreak of the Revolution had provided commercial opportunities for those in show business and consumer goods, now it was the turn of others to profit from the opportunities that came with military action. Seamstresses turned their talents to uniforms, and factories and foundries went into overdrive to supply equipment and arms. Church bells were melted down for cannon. Tanneries could barely keep up with the demand for harnesses.

As hostilities escalated, ordinary civilians became embroiled in the war effort. The wives of Paris were called upon to tear up their trousseaus for bandages. (Total mobilization–levée en masse–was officially declared by the Convention in August 1793, after a series of setbacks during the first half of that year.) Marie relates how, in response to a chronic shortage of gunpowder, ‘For the purpose of obtaining the quantity of saltpetre [a prime ingredient of explosives] that was required, they were obliged to resort to the most singular measures. It was imagined that it might be procured in considerable quantity from the mouldy substance commonly found on the walls of cellars. Every private house, therefore, underwent an examination to see what might be extracted from their subterranean premises.’ The austerity and enterprise of her later years probably originate from her experiences at this time. Like many civilian survivors of wars she had those distinctive badges of fortitude. A persistent shortage of animal tallow in the later years of the war was particularly difficult for the exhibition, as candlelight was crucial to the overall illusory magic of the display of figures.

But it was not just candles that were in short supply. For those in the entertainment business the sheer numbers of the men recruited as soldiers meant a drastic depletion of both customers and performers. Marie reported the enthusiasm with which people joined up, and how the quarter in which she lived ‘appeared almost cleared of men’. As Curtius became ever more involved in Jacobin affairs, as well as being involved in the National Guard, and as he stepped up his pursuit of his inheritance claim in Mayence in conditions more difficult by the day, Marie had to keep the exhibition afloat. Later on in England she recalled that, for the first time, in the summer of 1792 it was necessary to reduce admission charges to attract more customers. This year also saw grocery riots when, as well as bread, other foods including coffee and sugar were in short supply.

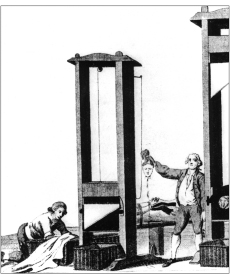

Marie was living in a city that was like an ideological building site, with drastic demolitions and radical conversions such as churches being declared Temples of Reason. In the course of the next two years, language and traditional systems for measuring time were all revised. New language was supposed to render old concepts obsolete. The King was demoted to Louis Capet, and the Duc d’Orléans became Philippe Egalité. Many public establishments pasted up posters proclaiming ‘The only title recognized here is that of citizen,’ but an anecdote from the theatre shows how hard it was to implement these changes. A prima donna at the Comédie-Française called for her lackeys, only to be told, ‘There are no more lackeys, we are all equal today.’ Unabashed, she replied, ‘Well then, call my brother lackeys!’ The one-size-fits-all ‘commune’ replaced the distinctions of hamlet, town and city. Meanwhile, the most ominous manifestation of equality was the newfangled instrument of capital punishment–the gleaming guillotine–which made its first appearance in the Place de Grève in April 1792.

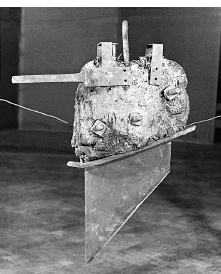

Historically, a protocol of execution meant that the supposed swiftness of beheading was the privilege of the well-bred criminal, while the riff-raff felons were subjected to burning, breaking on the wheel or hanging. Now the guillotine brought democracy to decapitation. As a new invention it captured the public imagination and was the talk of Paris; as a well-worn relic its fascination is undimmed. At the height of her fame in England, Marie allegedly bought the original guillotine blade and installed it in pride of place in the Chamber of Horrors. The catalogue entry read, ‘This relic was purchased by Madame Tussaud herself, together with the lunette, which held the victim’s head in position and the chopper which the executioner kept at hand for use should the guillotine knife fail–Sanson the original executioner vouching for the authenticity of the articles which were then in possession of his grandson.’ The whole was listed under the heading ‘The most extraordinary relic in the world’.

The guillotine blade bought from the Sanson family

In spite of the difficulties and the mounting tensions in the background, the exhibition remained a precise gauge of the mood of the people. The different acts of the unfolding drama were revealed by just a glance at the silent doormen, who were persuasive enough in their realism to entice people to pay up to see more. In the 1780s they had been dressed in the regalia of royal soldiers; in 1789 they had been reclothed in the simpler uniforms of the National Guard; now they had the distinctive uniform of the sans-culottes: long trousers, such as working men wore, rather than the knee-breeches (culottes) favoured by courtiers and professional men, with the all-important bonnet rouge on their heads–the red cap which according to Marie was ‘much worn at this time as the symbol of liberty, but proved more correctly the symbol of anarchy and was a great favourite with the vulgar’.

Whereas clothing had once followed the fads of fashion, now it had a more serious function as a political statement, with colour, cut and even degree of cleanliness all loaded with significance. It is not surprising that, as the Revolution progressed, the innovative fashion and lifestyle magazines that had appeared in the heady climate of the late 1780s fizzled out completely. Their ethos was not viable in a city that had lost its sparkle, and where dress was suddenly bound up with ideology. What Marie’s memoir omits in feelings and opinions, it supplies in detailed description of dress, like a talking pattern book. She witnessed the emergence of clothing as an integral aspect of political allegiance. The absent-minded who forgot to sport a patriotic cockade or to wear the correct republican accessories were putting themselves in real danger. Being out of date, once social death, would soon become a justification for a death sentence. The weight of importance Marie ascribes to clothing makes more sense in the context of her experiences of living at a time when appearances were judged so harshly, and could be used as evidence against you. An incident concerning her maid related by Madame de La Tour du Pin illustrates this:

She went out, dressed as always in the clothes normally worn by a maid in a good household, her apron white as snow. She had gone but a few steps along the street when a cook, her basket over her arm, pushed her into an alley and said to her, ‘Don’t you know, you wretched woman, that you will be arrested and guillotined if you wear an apron like that?’ My poor maid was astounded to find that she had risked death by observing a lifetime habit. She thanked the woman for saving her, hid her anti-republican apron, and hurried off to buy several lengths of coarse cloth to disguise herself, as she put it.

Wearing trousers was an overt anti-Establishment statement, and as class war intensified it became common practice for aristocrats to adopt an affected version of working-class dress. Marie relates how the Duc d’Orléans, now Philippe Egalité, in order to ally himself to their cause, donned the outfit of the sans-culottes. ‘It consisted of a short jacket, pantaloons and a round hat with a handkerchief worn sailor-fashion loose round the neck, with the ends long and hanging down, the shirt collar seen above.’ Contrived unkemptness was also part of the look. An Englishman in Paris at this time, Dr John Moore, remarked on the ‘great affectation of that plainness in dress and simplicity of expression that are supposed to belong to Republicans’. He relates how a well-connected acquaintance from one of the first families in France drew attention to himself at the theatre by his choice of clothes, ‘in boots, his hair cropped and his whole dress slovenly’. When this was commented on, he defended himself by saying that ‘he was accustoming himself to appear like a Republican.’

As the Revolution progressed, cleanliness was seen as subversive, to the extent that anyone bold enough to appear in a clean shirt was subjected to a barrage of insults. Marie relates how Marat conformed to this dress code, with ‘a dingy neglected appearance, not very clean’. Robespierre, however, did not embrace sartorial slovenliness, and was renowned for his high standards of personal grooming. Marie remembers him as ‘a perfect contrast to Marat, being fond of dress. He usually wore silk clothes and stockings, with buckles in his shoes; his hair powdered, with a short tail; was remarkably clean in his person, very fond of looking in the glass and arranging his neckcloth and frill.’ It seems very surprising that the man directing the Revolution and the strict arbiter of Revolutionary protocol should himself appear in such brazenly counter-Revolutionary garb. It was noted by, among others, the Revolutionary idealist Helen Maria Williams, who in a letter wrote, ‘While he called himself the leader of the sans-culottes, he never adopted the costume of this band.’

Named after their style of dress, the sans-culottes were the most important popular movement of the Revolution that surged in power in 1792. As work wear, their clothing defined a set of values and emphasized class difference. A pamphlet from 1793 entitled What is a Sans-Culotte? answers the question with a vivid picture and gives a good profile of Marie’s audience: ‘He’s a man who goes everywhere on his own two feet, who has none of the millions you’re all after, no mansions, no lackeys to wait on him, and who lives quite simply with his wife and children, if he has any, on the fifth floor. He is useful because he knows how to plough a field, handle a forge, saw a file, tile a roof, how to make shoes and to shed his blood to the last drop to save the republic.’ The sans-culottes were the rank-and-file workers, the legions who lived cheek by jowl in attics and tenements and whose chief concern in daily life was a full breadbin for the family. They were the artisans and craftsmen who worked in the Revolutionary hot spots of the Rue Saint-Antoine and the Rue Saint-Marcel, with their concentration of small workshops. They were the people who rejoiced the most with each blow to the old regime. They were also regulars at the waxworks, which shed its former associations with the court and, in pace with their rise to prominence, reinvented itself as a favourite sans-culotte entertainment.