12

‘Much Genteel Company’

MARIE’S DECISION IN the spring of 1808 to drop the Curtius connection and to trade under her own name had been born out of positive circumstances, chiefly a growing confidence in her own credibility as the proprietor of a popular entertainment. Local papers were fêting the ‘celebrated artiste Madame Tussaud’. The rebranding was a symbolic separation from the past, signifying that she was no longer merely the protégé of the great Curtius of Paris, preserving his fame: she was making her own. But by the end of the year she had to endure a much crueller cutting off from the original exhibition, which was as painful to her as it was unplanned.

It transpired that, while the provincial newspapers of Ireland were singing her praises, back in Paris François was sinking her assets. He had been slipping deeper and deeper into debt and was falling behind with loan repayments. Eventually he had no recourse but to sign over the entire Salon de Cire to his principal creditor, Madame Reiss. In the legalese that makes a precision instrument of words, a document dated 18 September 1808 details the settlement: ‘François Tussaud cedes to Mademoiselle Salome Reiss all the objects comprising the salon of figures known as the Cabinet of Curtius. These objects include all the wax figures, all the costumes, all of the moulds, all the mirrors, lustres and glass, which she may deem fitting. M. Tussaud hereby renounces any right in this regard.’ These few short sentences would have long-term consequences. It is not an exaggeration to say that they reoriented Marie’s life.

For a second time, while still savouring her hard-won freedom from contractual chains to Philipstal, she found herself a victim of legal process. It is hardly surprising that, as a white-haired grandmother, she cautioned her successors against the legal profession. Her great-grandsons recalled her favourite axiom: ‘Beware the three crows, the doctor, the lawyer and the priest.’

Precisely when Marie heard about her husband’s financial crisis is hard to establish. But the disposal, presumably without consulting her, of what had been her core asset, and in its heyday a leading attraction in Paris, seems to have been a point of no return for her marriage. And the loss of the family home magnified the emotional cost of her husband’s financial folly, for with the power of attorney that she had conferred on him he also downsized the household to the smaller rental property in the Rue des Fosses, which meant losing what had been a modest source of regular income. But almost outweighing emotional ramifications was the fact that his action deprived her of prime-location premises to which she could return to resume the family business. If this had been her original hope, then it was irredeemably dashed.

In one of her early letters home Marie had stated that the initial objective of her travels in England was to procure ‘a well-filled purse’. This implies that she had intended to return to Paris to reinvigorate the business with fresh funds. Yet it is interesting that, while she sent François bulletins about her takings, she never sent him any cash. She regaled him with impressive figures, but there is no record of her ever having sent anything back home from the day she left to the day she died. Perhaps his action was in part retaliation for a perceived lack of trust in his ability to handle money and a dwindling sense of pulling together as partners. Given his track record, though, her actions seem sensible more than selfish. Her one lapse of judgement was in granting him power of attorney. But, whatever their individual culpability in this turn of events, there was never a reconciliation. Marie never returned to Paris; she saw neither her mother nor her husband again, and little Francis–the son she had left aged two–would be a man of twenty-two before they were reunited in England.

At the age of forty-seven, then, with Joseph (Nini) now a boy of ten by her side, Marie’s quest for autonomy took on a different dimension. From 1808 onward she had new determination to secure the future of her sons, over and beyond her personal success. To this end she committed herself to the punishing lifestyle that was the lot of travelling showpeople. Although her fame peaked in the years when she settled in London, her twenty-seven years on tour, visiting and revisiting Scottish cities and significant market towns and large cities throughout the length and breadth of England, established her as a regular fixture in the cultural landscape. The future format of the exhibition evolved during this time, when she assumed her part in the constant colourful cavalcade of entertainers who lurched and lumbered on bad Georgian roads, bringing welcome bursts of entertainment to communities lacking the amenities of London. Importantly, this period marks Marie’s development as a doughty matriarch, and the emergence of ‘Madame Tussaud and Sons’ as a family business.

Her years on tour happened against a backdrop of social unrest. Popular discontent was exacerbated by the vanity and extravagance of the Prince Regent and his brothers, who inspired ridicule rather than respect. This played into the worst fears of those who felt the reverberations of the French Revolution were in danger of toppling the pedestal on which kingship was now perceived as being rather precariously placed. This insecurity resulted in a hard-line response to crowd control, of which the St Peter’s Field incident in Manchester in 1819 was a notoriously dramatic example. Some fifty thousand people had assembled to hear a radical speaker airing views on workers’ rights, and democracy. The sheer size of the crowd had alarmed the authorities, and troops were sent in. Their heavy-handed approach resulted in several fatalities and many more horrific injuries. A local paper called the debacle ‘The Peterloo Massacre’, a term which spread into wider circulation, and the name has stuck.

The crowd that might become a mob was a source of almost paranoid anxiety for many at this time, and even spontaneous gatherings fuelled anxieties. The small news stories of everyday life illustrate these fears, for example when a rumour that a house was haunted drew a fascinated crowd of would-be Georgian ghost-busters special constables were deployed to break it up, an event reported as ‘A great number of people assemble about a ghost.’ Caution prevailed, and that trouble was expected was evident in the standard announcement whenever a fair or public gathering had taken place without incident of ‘Perfect order was maintained’–like a sigh of relief. The British Museum, like many other institutions, took no chances: from 1780, when the Gordon rioters went on the rampage in Bloomsbury and razed Lord Mansfield’s house to the ground, until as late as 1863 there was a military presence at the gates.

Fear of the crowd was especially evident in attitudes to traditional entertainments, and a killjoy movement to suppress fairs, spearheaded by the Society for the Suppression of Vice, started to gather momentum. (In an article in the Edinburgh Review Sydney Smith, a friend of Charles Dickens, suggested that this society would be more aptly called the Society for Suppressing Vices of Those Whose Incomes Don’t Exceed £500.) The perceived danger was that the unbridled fun of workers en masse might erupt into civil disorder. The form that people’s pleasures should take was further complicated by the radical change in how people lived. The quickening pace of industrialization, concentrating vast numbers of workers in cities, also undermined the customary rural entertainments.

Imperceptibly, a great grey smog of earnestness starts billowing through these decades, turning entertainment more and more into an educational experience, engulfing the free spirit and pure fun of the traditional fairground pleasures. Creeping legislation, policing and finally calls for the suppression of fairs altogether signified a middle-class crusade. The battle cry was ‘rational recreation’, and those championing this cause became more numerous and more vociferous throughout the first half of the nineteenth century.

Marie’s own version of ‘utility and amusement’ was in perfect sync with the growing middle-class concern that pleasure should have a purpose beyond its own reward. She built her fortune on this belief as, in the Victorian era, it gradually developed from a preoccupation into an obsession. Rather as Curtius had been in the right place at the right time in pre-Revolutionary Paris, Marie shaped her own business in accordance with the gentrification of pleasure that was happening in Georgian and Regency England. With her carefully targeted marketing, there was no danger that her visitors would encounter anyone other than people like themselves. Her assurance of segregation and protection from the rowdy mob endeared her to the middle-class market that she was aiming at.

The England she toured was the land that William Cobbett, an acerbic commentator and critic of the existing social order, portrayed in Rural Rides: a place where corruption in politics was rife and reform deeply contentious. The oligarchic ethos was such that even public interest in the political process was regarded with suspicion, let alone the idea that ordinary people had the right to a participatory role. Of an adult population in England and Wales of around 7 million, fewer than 450,000 could vote. The inequality of the electoral system was taken up by writers. Whereas Cobbett used the Political Register to vent his spleen, Thomas Love Peacock used satire. His novel Melincourt described two types of borough: the city of No-Vote, a manufacturing town of over fifty thousand with no parliamentary representative, and the tiny community of One-Vote, ‘a solitary farm, of which the land was so poor and untractable, that it would not have been worth the while of any human being to cultivate it, had not the Duke of Rottenburgh found it very well worth his to pay his tenant for living there, to keep the honourable borough in existence’.

The reform issue sharpened political debate, and as and when the key opponents and supporters were in the spotlight they took up their places in Marie’s exhibition. For the second time in her life, the figures were indirectly contributing to debates about democracy. Her model of Cobbett had the rare distinction of a moving head, and the biographical description that went with the nodding figure summarized his self-made success: ‘Born of humble parents and by his own unaided genius raised himself to the highest station as a political character’. One feels that Marie would approve of that.

Her early years on the road were comparatively tranquil, yet physically testing. Her travels around Georgian England spanned the heyday of stagecoaches, inns and milestones, but the reality of transport at this time was markedly different from the nostalgic idyll which, with the addition of snow, has inspired endless Christmas cards and place mats. Most roads were slow and badly maintained. Turnpikes regulated only a small percentage of the total mileage, and mismanagement of cross-country roads was a constant gripe of the public. The improvements on major roads introduced by John McAdam from around 1816 were a catalyst for more efficient stagecoach services, but even these were uncomfortable and expensive, and the fact that rival companies took to dangerous racing on certain routes also made them hazardous. Marie and Joseph had to endure long cold journeys in winter, and dusty ones in summer. They sped ahead to be in time to take delivery of the figures, which were transported under canvas tarpaulins on sturdy freight wagons by the private carrier companies, who charged by weight, and transported such diverse cargo as flour, tallow, blacking and bones, and even the occasional painting dispatched by John Constable. Given the demands of nomadic existence and the rigours of setting up and publicizing the exhibition and producing new figures, as well as maintaining the existing ones, often damaged in transit, Marie’s sheer stamina seems to have been the underpinning of her success.

Notwithstanding the increased number of stagecoach services between London and major cities in the first thirty years of the nineteenth century, England before the steam age was a country characterized by communities more cut off from each other than connected. Journeys between the principal cities took days, when in the railway era they would take hours. The mail coach speeding through a town was often the main source of news from London. For most of the population, the capital felt as faraway and unfamiliar as a foreign city, existing in their minds as somewhere as exotic as it was remote.

For most people in the provinces news was old, unreliable and in short supply, and in this context Marie’s topical exhibition was a welcome arrival. To understand quite how prized news was, one only has to consider the circulation of newspapers. There were no daily newspapers published outside London until as late as 1855. The trade in second-hand newspapers was brisk, and many in the provinces paid to have old copies of the London papers sent to them. Subscription clubs were another resource for newshounds, and families would club together and share readership. These clubs ranged from ad-hoc affairs to more formal arrangements with proper reading rooms where subscribers could go to get their news fix for a guinea or so a year. W. H. Smith has its origins as a subscription club in the Strand. This thirst for the topical was a boon for Marie. Her colourful cast of people making the news was an immensely popular visual supplement to eyesight-challenging black print in a newspaper. It was also an enjoyable first-hand experience, as opposed to reading a newspaper that was not second-hand but more commonly twelfth-hand by the time it got to you.

The physical and cultural isolation in the provinces created a market for all manner of travelling shows. Their seemingly inexhaustible supply of wonders was a welcome respite from humdrum everyday life, and for a few days or weeks they brought colour and vibrancy, spectacle and novelty to communities starved of the types of entertainment that were in such rich supply in the capital. Londoners might relish the jewel in the crown of commercial entertainment that was William Bullock’s Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly, but there was nothing comparable to this Georgian equivalent of a multiplex outside the capital. Small market towns with limited facilities were reliant on the more rudimentary and less varied diversions that passed through, setting up in the marketplace. A doctor in a small town in Essex gives a flavour of what came round: ‘An exhibition on our right of a Giant, a Giantess, an Alibiness [sic], a native of Baffin’s Bay and a Dwarf very respectable. We had a Learned Pig and Punch on our left and in front some theatrical exhibition. All in very good order.’ There was clearly scope for enterprising showmen to supply more sophisticated entertainments. By prioritizing towns, Marie and the other commercial entertainers exploited the gradual shift of focus away from the rural communities, which had been the hub of the great fairs, to a growing urban audience with money to spend and time to spare.

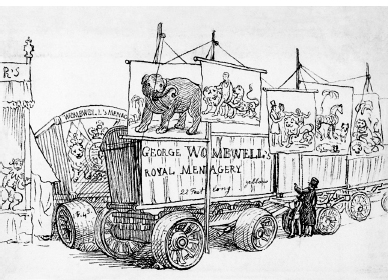

Her travelling years coincided with those of some other famous itinerant showmen, some of whom also built lasting family fortunes. Astley’s circus continued to draw huge crowds wherever it went. Of heart-throb status was the stunt rider Andrew Ducrow, who quickened female pulses with his somewhat racy flesh-coloured bodysuit. His fans paid tribute not just with flowers, but also by presenting him with whips, silver spurs and other equestrian tokens of their esteem. Another big name on the same circuit at the same time as Marie was the clown Grimaldi. A large part of his appeal was the way he chronicled the news of the day in a comic format. One of the most successful of her contemporary fellow commercial entertainments was George Wombwell’s menagerie. Just as one facet of Marie’s appeal was the way she popularized history by proving herself a judicious curator of relics and characters, George Wombwell’s menagerie enthralled by making natural history accessible. He boasted that his collection had as great a variety as Noah’s ark, and like Marie he maintained a punishing touring schedule, often overlapping with her–for example in Bath and Bristol. Records for his returns at Bartholomew Fair show just how popular his menagerie was. In just three days his takings were £1,800, which at sixpence a time means an impressive headcount. Wombwell had the showman’s knack of turning adversity into opportunity, and when his elephant died, prompting a rival circus to puff their elephant as ‘The Only Living Elephant in England’, his immediate response was to print posters offering the public the chance to see ‘The Only Dead Elephant in England’.

Wombwell’s Menagerie, drawing by George Scharf

It was not only men who made money in show business. Another contemporary of Marie’s was Sarah Beffen. She was similarly famous in her own lifetime, and similarly immortalized in the works of Charles Dickens–and in three novels (Nicholas Nickleby, The Old Curiosity Shop and Little Dorrit) compared to Marie’s sole mention in The Old Curiosity Shop. She was born without arms and legs, yet her dexterity as a miniaturist, a skill she perfected using her mouth and shoulder to control the paintbrush, won her such critical acclaim that she was for many years one of the biggest names on the fairs circuit. She even won royal recognition, and was granted a pension by George IV, who, mixing bad taste with bon mots, commented, ‘We cannot reward this lady for her handy-work, I will not give her alms, but I request she is paid for her industry.’

However, for the very few names who rose to national fame on this circuit, there were vast legions of entertainers who sank without trace. These peripheral people endured lives of real hardship living hand to mouth as they went from one town to the next, following the calendar of fairs, markets and race meetings. They constitute a shadowy underclass. A large number of them were open-air entertainers who moved among the crowds. Not enough pennies in the hat meant sleeping under the stars or in vermin-ridden lodgings where the calibre of patrons was such that the proprietors deemed it prudent to chain cutlery to the dining table. Of this number were the puppeteers, among whom Punch and Judy men were very well represented, the stilt-walkers and the knife-swallowers. There were even people with the skill to regurgitate live rats, who presumably took a crumb of comfort from the fact that if their acts went wrong, they could always restock rodents from their digs.

Marie knew that at any one time she had only the favour of the public between her and a swift descent to the destitution and oblivion that befell so many showpeople. She had no troupe or company to help to dilute disappointments, to give advice and to provide companionship: for many years it was just her and Joseph. But she had ambition, and this, iron will and artistic talent were her assets. She honed various survival strategies on tour, and flexibility about how long she stayed at any one place was key. Her pre-publicity wherever she opened was always carefully orchestrated, but she never committed herself to a set length of time for any specific visit. How long she stayed was always open-ended, and her publicity materials show how she often drummed up numbers by dramatically announcing imminent departure, only to defer it as required. In this way she kept her public hungry for her, and was never humiliated by their dwindling interest. It was a technique that served her well.

As far as we can establish from an early and battered ledger with columns of largely indecipherable entries, she managed to maintain a lifestyle of modest comfort. Her early letters hinted at respectable lodgings and these seem to have set a level that she maintained. Her assiduous record-keeping, with every penny of outgoings listed alongside takings, suggests that expenditure on presentation was a priority, as one would expect. Outlay on candles was considerable, to create the requisite ambience. Attention to the details of costumes and jewellery was always a source of personal pride, and the ledger hints at this too. She never compromised her high standards, and the wear and tear of touring did not prevent her from exhibiting immaculate figures in freshly laundered outfits–‘washerwoman’ and ‘soap’ are frequently listed in her costs. As for her own dress, austerity and sober respectability disposed her to a matronly style: there were no personal fripperies. A pint of porter, a pinch of snuff, the odd lottery ticket and theatre outing for sure–but in the main the evidence is of exemplary dedication to the exhibition, and her accounts are a record of frugality and practicality.

Along the way there were music lessons and a smart set of clothes for Joseph, for, much as her own childhood had been an apprenticeship for showmanship, so it was with her son. For a time Marie placed his wax likeness at the door, and encouraged visitors to compare the model to the young man in person. With fluent English (as reported home in early letters) and an engaging personality (again mentioned in letters), he was a good guide and assistant. A peripatetic life meant he had had limited opportunities for a proper schoolroom routine, but, given that they stayed in some places for months at a time, he may have dipped in to the ‘hedge’ schools–the informal, ad-hoc assemblies of juveniles co-ordinated in local communities by philanthropic clergy. We know he learned English very quickly, so he seems to have been a bright little boy, and most probably he was more literate than his mother. By 1814, when they were in Bath, he was even accorded the honour of being introduced as ‘J. Tussaud Proprietor’ in their publicity, as if at the age of sixteen this was a rite of passage in the life of a budding showman, although his mother, as ‘Madame Tussaud, Artist’, still topped the bill in bigger letters. As he grew up he became more active on the artistic side–the music and staging–and in 1815 he was put in charge of making silhouette portraits of the public, which at one shilling and sixpence proved to be a lucrative and popular sideline.

Whatever their individual specialities, and the differences in the size of their shows, the itinerant showfolk specialized in hyperbole, hoax and spectacle. The picture of the bloody-jowled wild beast on the outside of the van often bore no relation to the superannuated mangy creature within. The ‘Black Giantesses’ announced on posters were often impostors on platform heels with cork-blackened faces; the ‘Pig-faced Ladies’ were dogs or bears with shaved faces, draped in poke bonnets and voluminous clothes to complete the disguise. Some acts left spectators completely flummoxed, such as the feats of Chabert, the Fire King, whose seemingly fireproof constitution made him a household name. His star turn took the celebrity chef concept to a whole new level when he made himself the chief ingredient of his recipe for entertainment. In front of packed audiences, he entered a hot oven in which slabs of steak and mutton were simultaneously cooking. The oven had an aperture through which he conversed with the audience, and at the end, to prove the heat that he had endured, he shared the meat–cooked to perfection. The Times laconically noted that the joints were devoured with such avidity by the spectators that ‘had Monsieur Chabert himself been sufficiently baked, they would have proceeded to a Caribbean banquet’.

Whether on a formal stage or in an informal caravan or booth, the exoticism and escapism on offer elicited a wide range of emotions. There were gasps of wonder, disgust and delight, and occasionally disappointment–as memorably recorded by one of the spectators of the Living Skeleton. As well known in his day as Chabert, the Living Skeleton did not live up to his reputation as far as Prince Pückler-Muskau was concerned: ‘The Living Skeleton was a very ordinary sized man, not much thinner than I. As an excuse for our disappointment, we were assured that when he arrived from France he was a skeleton, but that since he had eaten good English beefsteaks it had been impossible to curb his tendency to corpulence.’

Gradually the rich array of variety acts that had been the back-cloth to Marie’s early years on tour started to be overlaid by educational entertainments, as spectacle alone started to be regarded as too frivolous. As audiences became more discriminating, some of Marie’s touring companions could not count on the full houses they had once enjoyed–the man who played his chin could not really compete with the mechanical genius of Mr Haddock’s Androides. ‘Philosophical experiments, rational, fashionable and entertaining selections’, as one showman described his more cerebral programme. Such learned fare started to eclipse the interest in Siamese twins and learned geese. The days of The Wonderful American Hen were numbered, but, with three wings and four legs, at least the bird billed in her heyday as ‘The Greatest Living Curiosity in the World’ could make a comeback as the star turn on a dining table. For some fifteen years Signor Capelli’s Learned Cats had enchanted audiences by imitating human actions–roasting coffee, grinding knives and turning a spit–but now they were damned as being more ‘industrious than intellectual’. By the time Marie stops touring there are almost signs of freak fatigue, in favour of educational content. She exemplifies the transition from the traditional innocent fun of the fair to a more elevated style of recreation centred on the town, not the country, and tapping into the new sensibility of aspiration.

Freakshow caravan, drawing by George Scharf

Although she followed the circuit established by the fairs, many of which kept to a seasonal calendar and were often linked to race meetings, livestock auctions or specialized markets, she kept herself well apart from the open-air temporary set-up of the booth and tent. She hired premises attached to public houses, hotels, and theatres, and where they were available she customized many of the comparatively new assembly rooms, which from the late eighteenth century were an innovative civic amenity in provincial towns. Some assembly rooms had separate function rooms, and sometimes Marie was able to maintain her exhibition in one part of the rooms while the ball season was ongoing. On one occasion, in York, she turned this shared-premises arrangement into a public-relations opportunity. When the distinguished guests attending the ball stopped their quadrilles and waltzes to retire for tea, Joseph drew back the canvas screen concealing the space dedicated to their exhibition, and before resuming dancing the guests were able to enjoy the interlude by inspecting the figures. The proceeds of their private view were donated to the Fund for Distressed Manufacturers–a charitable act which was reported in the press, thereby generating a very favourable impression of Madame Tussaud as a woman with a social conscience, an impression that one conjectures was part of her calculated publicity campaign, in which everything she did worked towards creating a very particular impression of herself in the public eye.

Of all the premises where she exhibited, assembly rooms were the perfect milieu for Madame Tussaud. They were a bricks and mortar, or rather gilded-cornice and chandelier-bedecked, manifestation of her ethos. They were the parade grounds of polite society, a forum for elegant recreation. Their value as a venue for social mixing, a place to see and be seen, was captured by Jane Austen. When Mr Darcy makes his entrance in the assembly room at Meryton, the room crackles with ‘the report which was in general circulation within five minutes after his entrance, of his having ten thousand a year’. Designed in part for balls, they were equipped to accommodate orchestras, and a high standard of lighting was also a feature. The overarching aim was to create a congenial environment in which to display the dash and dazzle of provincial society at play. These amenities lent themselves particularly well to Marie’s personal style of promenade, which she developed in the 1820s, making music a crucial component of the experience. She cultivated an environment where people-watching was a legitimate part of the pleasure. After a pleasant perambulation around her wax figures, visitors could avail themselves of strategically placed ottomans and chairs and appraise those still inspecting the exhibits. Just as the study of human nature informs her fiction, in life Jane Austen was a compulsive people-watcher, and she testifies to the attraction of exhibitions as a social experience, confessing, ‘My preference for men and women always inclines me to pay more attention to the company than the sight.’

From a faded and fragmented paper trail of handbills, exhibition ephemera and provincial newspapers, an impression of Marie’s progress can be assembled. Her itinerary encompasses the fashionable resorts of Cheltenham, Bath and Brighton–cities whose fortunes were founded on the leisure industry–and significant trading ports such as Bristol, Portsmouth and Yarmouth. It covers the burgeoning manufacturing conurbations like Birmingham, and the industrial engines of urban growth that were Liverpool and Manchester. Outside London, Manchester was the city to which she returned most often, visiting it six times between 1812 and 1829. But her success was not confined to the smoke-choked industrial north. In Oxford in 1832, as she moved ever closer to London, her exhibition was ‘visited by thousands’ and, as if describing works at the Villa Borghese rather than wax mannequins, Jackson’s Oxford Journal enthused about her stylish presentation and the overall impact of her skilful design that combined ‘beautiful freshness of painting, bold relief of statuary and the actual effect of dress and ornament united’.

The elements common to the different-sized communities that Marie visited were an affluent middle class and the presence of a local press through which she could communicate with her target audience. Marie was clear about her audience, and it is evident from her publicity that it was the queen bees, not the worker bees, she wanted to attract. ‘No improper persons will be admitted’ was her cautionary warning in the Bristol Mercury in the summer of 1823. Her preferred clientele was that which she evidently attracted in Chelmsford in 1825, when, reviewing her newly opened exhibition there, the local paper reported the attendance of ‘much genteel company’.

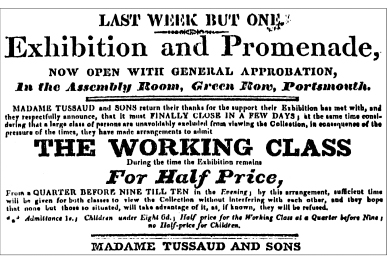

‘Madame Tussaud respectfully acquaints the gentry’ became the standard opening in her publicity notices that announced the arrival of her exhibition. A notice in Newcastle-upon-Tyne in June 1811 went one rung higher up the social ladder: ‘Madame Tussaud Artist respectfully informs the nobility and gentry of Newcastle and its vicinity that the Grand Cabinet of Sixty Figures, which was lately exhibited in Edinburgh with universal approbation, is now open for inspection at the White Hart Inn, Old Flesh Market.’ She showed almost no interest in wooing the working class. One notable exception is evident on a poster that she had pasted around Portsmouth towards the end of her touring years in 1830:

Considering that a large class of persons are unavoidably excluded from viewing the Collection, in consequence of the pressure of the time, Madame Tussaud and Sons have made arrangements to admit THE WORKING CLASS during the time the exhibition remains for half price, from a quarter before nine till ten in the evening. By this arrangement sufficient time will be given for both classes to view the collection without interfering with each other, and they hope that none but those so situated will take advantage of it, as if known, they will be refused.

This rare notice hints at a norm of social segregation that is incomprehensible today when mass-market interest is the focus of popular culture. It also betrays a certain cynicism on Marie’s part in thinking that the ‘gentry’, so dear to her, would be inclined to pass themselves off as workers and cheat their way into her exhibition like cheapskates. For the workers, even the reduced rate of sixpence was still prohibitive in the context of the standard penny charges at fairs for everything from topical peep shows that were a prized form of news for the illiterate to the unconvincing waxworks that were a staple of the ‘raree-show’ scene.

In the small print of local papers, the growth of the exhibition can also be monitored. The core collection of around thirty figures with which she arrived in 1802 had already doubled by 1805, when the Waterford Mirror commended her ‘sixty capital figures’ and ‘several uncommon objects’ to ‘all admirers of real genius and talent’. In 1815, when she was weaving her way around the coast of Cornwall, the Taunton Courier and the Western Advertiser were advertising her ‘unrivalled collection of figures as large as life’, comprising ‘83 public characters lately exhibited in Paris, London, Dublin and Edinburgh’ and now–something of a comedown–at ‘Mr Knight’s Lower Rooms, North Street, Taunton’. By the spring of 1819 the Norwich Mercury was alerting the public to their chance to see ‘Ninety Public Characters’ at the Large Room in the Angel Inn. In the winter of the same year the Derby Mercury referred to ‘one hundred figures of personages of different periods and nations, illustrious for their rank, talents or virtues; remarkable for their personal appearance, misfortunes or sufferings, or of notorious celebrity for their crimes and vices’.

As the wax figures multiplied, an impressive growth spurt was also evident in the number of illustrious patrons. Whereas before she announced her own exhibition, now on her publicity material there was a fanfare of royal connections preceding her arrival. In Taunton, in 1815, her handbills boast the patronage of ‘their Royal Highnesses the Duke and Duchess of York and Monsieur Comte D’Artois’. In January 1819 she trumpets the arrival of her collection in Norwich by highlighting the patronage it has received from ‘his most Christian majesty Louis XVIII, the late Royal Family of France, their Royal Highnesses the Duke and Duchess of York and Her Grace the Duchess of Wellington’. By the spring of 1826, when she opens in the assembly room in Lincoln, she is styling herself as Madame Tussaud, Artist, niece to the celebrated Curtius of Paris, and artiste to her late Royal Highness Madame Elizabeth. (The degree to which she capitalized on her early life in France is evident in a poster from 1816 in which she announces herself as ‘Madame Tussaud, lately arrived from the Continent’, even though, having been in the country for thirteen years, she was hardly packet-ship fresh.) By giving herself an air of social superiority, she adds another dimension of interest to her collection that helps to distinguish her from rival touring waxworks. In fact later on there is legitimacy to her claims of distinguished patrons, but on tour the alleged noble connections and associations that feature in her publicity are all part of the licence with the truth that is the showman’s prerogative.

Following the same wheel ruts as Marie’s wagons were numerous entertainments whose proprietors similarly puffed up the credentials of their exhibits. The proud presenter of the Scientific Java Sparrows challenged all prejudices about the brain power of birds:

Having finished their education at the University of Oxford, where they met with the greatest approbation from the Vice-Chancellor, the Collegians, and the Mayor and Inhabitants of that learned city, the birds now presented to the particular notice of the nobility and public have required no less than three years to complete their education. They are now perfect in the following seven languages: Chinese, English, French, German, Italian, Russian and Spanish.

Often it was the singularity of the size of an animal or human that was the bait to customers. Aged fifteen and allegedly ‘eight feet around’, Miss Holmes, a native of Prescot, Lancashire, was billed as ‘the most extraordinary phenomenon of nature, a Gigantic Fat Girl’. Working people and servants could see her for threepence, tradespeople sixpence, and ladies and gentlemen a shilling. Double bills highlighting contrast were also popular. The Devonshire Giant Ox and Tom Thumb’s Fairy Cow were a popular pair, and Miss Hales the Norfolk Giantess went down well alongside the ‘smallest person in creation’. Of course, lest punters feel discomfort in gawping at their fellow creatures, a growing trend was to couch voyeurism in terms of educational value. In the case of Miss Hales, her proprietor resorted to verse:

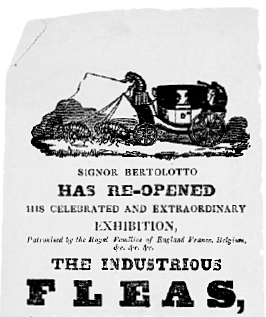

Flea Mail–Signor Bertolotto’s Flea-drawn Mail Coach

Exhibitions like this may to us be of use–

What a contrast of creatures this world can produce!

From such wonders eccentric presented to view

We now may our study of Nature pursue.

The smallest performers on the circuit were the those in the flea circuses, whose popularity moved one reviewer to poetry:

No more from our blankets with hop, step and jump

With bloodthirsty purpose you dart on our…

With other performances now you delight us,

And prove you can do summat better than bite us.

These tiny stars were one of the oldest traditional attractions. Flea-circus purists made a distinction between flea performers that were actually wired together in intricate metal harnesses and those that were an optical illusion.

It is unclear which of these categories Marie’s flea circus fell into, but, before her upward mobility meant such frivolities were anathema to her, her fleas had had their fans. The Worcester Herald had enjoyed seeing the French imperial coach ‘pulled by one of those sable-coloured blanket harlequins commonly called fleas’. But her troupe was outclassed by a rival’s rendition of ‘Flea Mail–an accurate representation of England’s Pride, her dashing Mail featuring a Flea Coachman who handles his whip in the most approved style and a flea-guard who flourishes his horn.’

At the other end of the scale was an immensely popular touring show that gave a novel literalness to the concept of a whale of a time. The skeleton of a giant whale was the basis of a hands-on entertainment which packed in people of all ages. It was arranged in such a way as to form a series of carriages, which created an extensive gallery ‘through which hundreds can pass beneath the massive vertebrae and between the giant ribs of this once mighty inhabitant of the Northern deep’. In Liverpool a party of junior Jonahs entered the whale. The local paper marvelled at how many of them could be fitted into the mouth cavity alone–‘the capacious maw…could fit in with ease one hundred and fifty-two human beings in the shape of tender juveniles of the infant school standing within its mouth at one time.’

This was the richly textured world of popular entertainment that Marie inhabited, and the passing of which Dickens mourned in The Old Curiosity Shop. In the time that Marie toured, she was witnessing the twilight years of the traditional travelling shows, and she herself was germinating the new style of recreation for a different generation. The longer she toured, the more her exhibition grew in size and scope, attracting bigger crowds. Her return visits with new material were an important facet of her marketing initiative, which was designed to cement her reputation as a reliable purveyor of educational entertainment, like a public-information service, on what was an increasingly competitive circuit. Impressive attendance figures start to appear in her publicity. For example, in advance of her arrival in Liverpool in the spring of 1821 she states in her publicity that 30,020 people have just visited her in Manchester. In the Bristol Mercury of 18 August 1823 the numbers are even more impressive: ‘Her celebrated collection of figures [was] lately viewed in Manchester, Liverpool and Birmingham by upwards of 100,000 people.’ In January 1826, her advance publicity before opening in Bury St Edmunds alludes to earlier success on tour by stating that in the cities of Oxford and Cambridge alone 18,000 people had visited her collection.

As she expanded the exhibition, the drawbacks of life on the move started to become more apparent, specifically the need for space. It became difficult both to transport the figures and props from place to place and to locate premises of the right size to set them up for maximum effect. While the assembly rooms tended to be ideally proportioned for the purposes of creating a theatrical backdrop, with still enough space between the figures to permit the public to walk around, not every town she visited had one, and in those that did it was not always free for her to hire. This meant that sometimes she had to make do with constricted accommodation that cramped her style. During her visit to Norwich in February 1819 the local paper opined that the figures would have benefited greatly from being displayed in larger premises, then commenting:

On women, kings, generals and statesmen you stumble,

And of characters here meet a very strange jumble.

In Liverpool, in 1821, another facet of the space problem was taken up by the press. Transport charges for the network of carrier services that criss-crossed the country were generally based on bulk and weight. There was therefore an incentive to try to keep the figures as compact as possible. But while reducing dimensions was an effective strategy for transport purposes, it was detrimental to display. An article in The Kaleidoscope, a local periodical, criticized the way that, in order to fit more figures into the exhibition, Madame Tussaud had scaled down the bodies, resulting in an ‘anatomical want of proportion’. This lessened the impact of the finely executed heads, and obviously affected the overall illusion of lifelikeness. This charge of ‘deficiency of appropriate attitude’ was obviously taken to heart by Marie, and by the end of the year, on a return visit, the local press remarked on the improvement, noting ‘the major part of figures are now as correct in expression and formation of limbs and attitudes as they are in the faces.’ Her commitment to improving her collection appears in her publicity when revisiting Liverpool and Manchester, which announces, ‘80 great and astonishing changes since it has been absent’.

As she develops a relationship with the public and a reputation for excellence, she becomes more mindful of not risking anything that would damage the good opinion of her show. Rather than cramming her figures into rooms, she adopts a more sophisticated approach to display. Ledgers show bills for glaziers, carpenters and gilding. Lengths of material are also listed, and one can sense her developing the panache for presentation that would reach its fullest expression when she acquired permanent premises. The effort she put into set design was evident in 1822 when, for a Christmas season, she redecorated the theatre in Preston especially for her exhibition, and put a platform across the pit so that she had ample space on which to make a suitably dramatic backdrop for her representation of the previous year’s coronation of George IV. Similarly in 1824, when she reached Northampton and found that the town hall was not sufficiently large to do justice to her display, she went to considerable effort to customize the local theatre. The theatre pit was again boarded over, so that, in conjunction with the area of the stage, she boasted that she had created ‘one of the largest rooms in Northampton’.

A recurrent theme, both in the critical acclaim she gets from the public and in her own publicity material, is the lifelike illusion of her figures, and their interest as accurate likenesses of specific people. Evaluating the figures of the French royal family, for example, the local paper in Worcester in 1814 remarks, ‘The resemblances are allowed to be most accurate.’ With the French material, an extra frisson of interest was generated by Marie’s claims that the faces were cast directly from the flesh-and-blood subjects–something that she emphasized in all forms of publicity. This immediacy was especially powerful in the death-like authenticity of her human relics of the Revolution and the macabre exhibits that were her signature pieces. In Norwich in 1819, for example, Marat is billed as her star attraction, ‘in this figure represented immediately after receiving the mortal wound’. She goes on to state, ‘The model was taken from his body on the spot, by Madame Tussaud, by order of the National Assembly, and was universally allowed to be a most exact resemblance, both to the person and physiognomy of the above-mentioned celebrated but atrocious character.’ This sense of eyewitness proximity to people of both historical and current interest was particularly compelling. The patina of authenticity, from the tint of the flesh to the colour of the hair and the disarming glint of glass eyes, exerted a great fascination at a time when information about people tended to be disseminated through print, monochrome engravings or the formal aesthetic of fine art. Her convincing replicas gave those who saw them that uncanny sensation of optical trickery that, even in an age when we are saturated with images of the famous, makes you stop in your tracks in front of a life-size likeness. For as Chambers’s Journal pointed out in 1881 a wax mannequin exerts a particular sensation that affords a greater depth of intimacy than either a photograph or a statue. ‘One can fearlessly criticise the crowned kings of England’ and, conversely and even more compelling, ‘one can enter securely into a lair of thieves and murderers and feel with a chill that they are shockingly like commonplace mortals.’ One can stare and scrutinise at close quarters without redress, ‘a popular luxury never possible among the convenances of real life.’

The impact was the same whether in experiencing the past in the present by getting close to the dead subjects of recent history or in having the thrill of standing next to the human subjects of the news stories of the day. In this way her wax figures anticipate the function that would eventually be fulfilled by photographs, capturing likeness in a way that transcends temporal and physical boundaries. During her touring years Madame Tussaud began a process that would evolve dramatically in the 1840s, as advances in the technology for reproducing images were a catalyst for culture becoming progressively more pictorial, ephemeral and celebrity-oriented. Long before this, she had turned a visual medium into a collective cultural frame of reference, and in so doing had established a prototype of the network by means of which celebrity culture would take off. Familiarity breeds fame, and, at a time when the norm was unfamiliarity with what people in public life looked like, her likenesses of the famous and infamous provided a large segment of the population with a pool of visual images that had an impact on how they interpreted both history and current affairs. She enabled the public in the provinces to visualize the people they were hearing about in the limited flow of information that other media supplied. This shared information in turn affected how they related to each other, as common interest in the famous and infamous started to become a cohesive element in society, closing up a gap between the urban metropolitan culture focused on London and the rest of the country. In this way with communality of interest, and her appeal to middle-class values, Marie can truly be said to have been a pioneer of a form of popular culture that burgeoned in the Victorian era. She bridged the demographic divide with her earnestly respectable form of entertainment–closing the gap between the vastly different cultural milieux of curators, collectors and formal display and the caravans, barkers and booths.

A selling point that she developed was giving glimpses of the great and the good on occasions to which the public did not have access, but which were of great topical and national interest–notably coronations. This opportunity for presence by proxy, being able to get close to three-dimensional replicas of people in public life on state occasions, was an integral part of the market Marie exploited. She also capitalized on public interest in significant deaths, in which regard her quick response worked rather like the commemorative supplements rushed out today by newspapers. Before improved communications carried news quickly to the provinces, Marie took the news of the day on tour in an engaging visual format. Unlike reading a report in private, the public could satisfy their curiosity by means of a civilized and sociable experience, a participatory form of becoming up to date and au fait.

It is worth noting that Marie was not the sole purveyor of such material. At the same time that she was touring, other waxworks were presenting similar subject matter. For example, the national outpourings of grief first at the death of Nelson in 1805 and then later at that of Princess Charlotte, created a fertile market for funerary wax facsimiles, and an almost perpetual cortège of sombre entertainments took to the roads. Rather as Nelson’s mortal remains had been pickled to preserve them so that he was in good shape for his funeral, after death he was preserved in wax. A full-size portrait officially commissioned from the celebrated society modeller Catherine Andras was installed in Westminster Abbey, and his likeness was an immensely popular subject in travelling exhibitions. Mr Bradley’s star attraction for some time was his tableau of the Death of the Immortal Nelson in the hour of victory. Bradley assured his public, ‘The big sorrow of the mournful sight of the dying hero is so powerfully and pathetically expressed that the most insensible human being cannot look upon it without in some sort sharing in the grief.’

The death in childbirth of Princess Charlotte, daughter of the future George IV, in 1817 was an enduringly popular wax weepie for years afterwards. Churchman’s grand exhibition went all over the country, presenting the ‘splendid and solemn spectacle, of her royal and serene highness the Princess Charlotte and her infant child lying in state as in the lower lodge Windsor. All the splendid arrangements have been faithfully copied.’ Coffins covered in crimson velvet and the sombre drapery of death were all part of the mournful theatricality. The appeal to the wider public was obvious. ‘To the thousands who were disappointed in obtaining admission at Windsor, this facsimile will be seen with avidity and the sorrowing millions of the empire will be peculiarly interested in beholding so august a ceremonial of respect to the presumptive heiress of the British throne.’ Echoing the enthusiasm for taking part in mourning rituals for Diana Princess of Wales, the appeal to the public of grieving by proxy for ‘England’s Rose’ by going to see commemorative wax displays was a boon to waxwork shows.

Marie also faced rivalry from one of her own sex. Madame Hoyo, while more downmarket with her threepenny tariff for the working classes, carved out a good living on the same circuit. Her most famous work was tantamount to a wax autopsy of Samson, depicting his exposed interior and the muscles, veins and arteries of the left arm. She too offered The Great Immortal Nelson, who appeared as large as life with Fame crowning him with a wreath of laurels, and in 1821 she was able to create a double bill which also showed Napoleon Bonaparte in his last moments.

Considering the competition Marie faced during the touring years, with some of it showing almost identical subject matter, her lasting success is even more impressive. For example, when Mr Bradley’s waxwork exhibition opened in Manchester in 1818 after a successful run in London it displayed seventy-seven public characters modelled from life to form ‘the most brilliant, splendid and striking assembly of the most illustrious personages in Europe’. Alongside the English royal family were figures of Napoleon, Voltaire and the statutory grizzly exhibit of a contemporary criminal–in this case the head of Jeremiah Brandreth as it appeared after his execution at Derby for high treason. Offering topicality and sensation, the pageantry of royalty and the thrills of real-life crime, these shows were the travelling tabloids of their day. Many of them occupied the same price band as Marie, one shilling entrance and a catalogue for sixpence, while some, like Ewing’s, offered similar fare for half the price, with admission set at threepence for working people and children.

One of the factors that helped to set the seal on Marie’s success was her considerable ability as a sculptor, directed and developed by Curtius under the mantle of his own reputation. Her outstanding artistic ability, coupled with the unique credentials of her French figures and relics and their status as autobiographical material, distinguished her from more run-of-the mill waxwork shows. She herself was not shy of trumpeting her pre-eminence. In advertisements she often describes her collection as ‘unrivalled’ and cites her unique ‘composition’, meaning the particular blend of waxes that Curtius had passed on to her, as the reason that her own portraits are ‘very superior to any figures in wax that can possibly be made’. The Taunton Courier in 1815 was but one of a number of papers that asserted the superiority of a good collection of wax figures over the ‘faint resemblance’ afforded by medals, engravings and paintings, which ‘are generally deficient in character of contemporary greatness’. It favoured the realism whereby ‘the characters of the past and present day are brought before the eye with all the force of the actual, exact and almost speaking figure in its proper costume.’(The costume had been an integral part of the overall effect in Paris, and Marie did not skimp on it now.) Typical of the good reception she received on tour was a comment in the Portsmouth local paper in 1816: ‘We never met with deception so complete, nor did we think it possible to give to inanimate substance so perfect an appearance of life and nature.’

The Manchester Mercury in 1820 conveys the disorientation that, then as now, is part of the attraction of viewing a convincing collection of waxworks: ‘The effect of the whole is highly imposing, indeed, so admirably are they executed, and the arrangement of them so natural and judicious, that the visitor cannot for some time divest himself of the idea that he is in the midst of a brilliant assemblage of animated beings; and he is not unfrequently on the point of expressing his admiration, and addressing himself to some one or other of them as a fellow spectator.’

The standard faux pas of mistaking models for people and vice versa was incorporated into Marie’s publicity repertoire. A case of mistaken identity that happened in Rochester in 1818 was widely reported. During a tour of the exhibition a young woman who had made vocal observations on several figures apparently came to a model of an officer in uniform. Not recognizing his identity, and speaking to herself as she thought, she said, ‘Pray who are you?’ The report continued, ‘To her great surprise and confusion the supposed model bowed very politely and replied “My name, madam, is Captain…of the…Regiment, and very much at your service.” On recovering herself, the lady observed “I beg your pardon, captain, for my mistake, and must confess that in the involuntary compliment I paid to the exhibition I cut a rather sorry figure myself.” ’

Similar anecdotes centre on the self-portrait of Marie. One of her stock stories was that a well-to-do woman was offered a catalogue at the entrance by Madame Tussaud but declined. She then changed her mind, and spotting Madame Tussaud in the centre of the room approached her and asked for a catalogue. As the Lincoln paper reported it, ‘Receiving no answer [she] turned away highly chagrined at the supposed rudeness of MT.’ Of course the mistake was then revealed when the visitor discovered that ‘It was nothing more than the representative of Madame that she had been addressing, and she now readily excused her want of politeness.’ A characteristic of Marie’s marketing prowess was the way she played the press. She proved herself extremely efficient in the art of self-propaganda, and her own fingerprints can be seen on some publicity that is presented as being independent. It is clear that she ‘planted’ stories in the press in the style of ‘advertorial’–not only amusing anecdotes, but also reports of her charitable donations.

A distinction worth mentioning is between ‘lifelike’, the effect of the illusion she created with her figures, and ‘from life’, which is the standard description of the method of modelling. There is a disparity between the illusion of first-hand authenticity that so impressed the visitors and the fact that most likenesses were derived from secondhand sources. In the punishing schedule that Marie adopted during her touring years, it would have been unfeasible for her to travel to take formal sittings with the famous as and when they were of topical interest. Not only that, one wonders whether she would have been granted sittings with many of the distinguished people she portrayed, given that she was going to profit from the display of their image, and that she could reproduce it ad infinitum in a commercial context. This makes her skill and productivity even more impressive, working on the road without a dedicated studio and relying on such secondary sources as engravings, busts and reproductions of portraits. Her contemporaries were under no illusions about this practice. In 1819 the Derby Mercury, writing about her exhibition, commented on ‘Features represented with the utmost accuracy, most of the models and living subjects being modelled from life, and the rest copied from the finest statues, and the most faithful portraits are displayed at full length in their proper costume.’

Although she makes much of her French material being produced by direct from-the-flesh casting, or modelling from first-hand observation of living subjects, and emphasizes this with autobiographical anecdotes and reminiscences, she is less insistent upon this with the figures she makes in her travelling years. For example, she states in her catalogue that her popular figure of Princess Charlotte was ‘taken by kind permission of P. Turnerelli from the beautiful and celebrated model’. As Sculptor in Ordinary to the royal family, Peter Turnerelli produced a succession of royal likenesses in plaster for the mass market that would have been an easily accessible and useful source for Marie when she was on the move. She also acknowledged his bust of the Irish patriot Daniel O’Connell, ‘for which Mr O’Connell gave sittings in Dublin’. A figure of George IV, in honour of his coronation, is described as ‘taken from a bust recently modelled from life’. Later, more information is given on the pose of the King, which is described as ‘an attitude copied from a picture by Sir Thomas Lawrence’. The Duke of Wellington is described as ‘taken from a bust executed by a celebrated artist in 1812’. During one of her return visits to Edinburgh, in 1828, a portrait likeness of Lord Byron, described as ‘taken from life in Italy’, was displayed beside a likeness of Sir Walter Scott, described as ‘taken from life by Madame Tussaud’, when in fact it has all the signs of having been copied from a bust of the great novelist by Sir Francis Chantrey. This literary duo have extra interest because they afford a rare recorded example of the way in which Marie produced figures in response to public demand. As the local paper reported, she was ‘anxious to meet the wishes of her visitors who pressed her to model a likeness of Lord Byron in order that they might see together two of the greatest living poets of modern times’.

‘From life’ was therefore an elastic term. Sometimes, indeed, it meant from death, and again in this context it was not necessarily Marie’s own hands that had coated the features of a dead criminal with liquid plaster. There is some evidence that Marie bought a collection of death masks of executed felons from a surgeon in Bristol called Richard Smith. This may have been the basis of some of her own wax representations of criminals of public interest. For example, the Liverpool Mercury announced in 1829 that she had added to her collection ‘a likeness of the Monster Burke said to be taken from a mask from his face. As this is known to be the only certain method of producing a perfect resemblance, we have no doubt that it will cause her exhibition to be crowded by persons anxious to see the features of a wretch whose crimes have hardly any parallel.’

The basis of Marie’s popularity was the demand to know what famous people looked like in real life–especially Napoleon, whose changing fortunes did nothing to dim his allure. He remained a giant in the public imagination, and Marie capitalized on the limitations of caricatures to satisfy intense curiosity about his likeness. A month after the Battle of Waterloo, Napoleon had surrendered to the British, handing himself over to Captain Maitland of the Bellerophon. When in August 1815 the most feared and fascinating figure in contemporary life finally came in sight of the shores of the country he had for so long threatened to invade there was a national sensation. His status as a captive on board a British naval frigate merely enhanced his appeal. Improvised flotillas of sightseers swamped Plymouth harbour, and anyone with a watertight vessel charged up to twenty guineas to row the curious alongside the ship for a glimpse of the fallen enemy. An eyewitness estimated that there were not less than ten thousand bobbing up and down in boats with their eyes fixed on the frigate’s deck, where from time to time Napoleon indulged them by presenting himself. The overcrowded harbour even claimed casualties, as a handful of sightseers drowned in their eagerness to get a look. Newspaper columns were crammed with details of the captive’s physical appearance, noting that he was now very corpulent.

Marie transferred Napoleon’s in-the-flesh allure to an in-the-wax opportunity, offering a more accessible and less hazardous chance to gawp. With Marie’s figure of the fallen Emperor, the public were also guaranteed an unrestricted view, which they could scrutinize and talk about in an unhurried and uninhibited way. A catalogue dating from 1818 describes a full-length portrait of Napoleon ‘taken when he was on board the Bellerophon off Torbay 1815’, and comments, ‘He who once could make the mightiest monarchs tremble at his frown, at last is himself become an object of pity.’ This is an example of Marie relying on a secondary source to make a topical crowd-pleaser, for none of the public were permitted to board the boat. Whether she used her preexisting image of the Emperor from the days of the Directory is unclear, but another possibility is that she based an updated model on the famous portrait by Sir Charles Eastlake, which he made from sketches taken alongside the Bellerophon. This painting was exhibited in London with several certificates testifying to its likeness to the ex-Emperor, and it was so popular that it made the fortune of the painter.

Marie did well with her own representation, and in the years after Waterloo she would have been keenly aware of the burgeoning market for Napoleon memorabilia. When she was on tour she would have noted the extraordinary success of Napoleon’s carriage that was captured at Waterloo–after a sell-out run in London, where it was displayed by William Bullock at the Egyptian Hall, it went on a national tour drawing huge crowds. She probably even saw the newspaper reports, in 1818, that the famous carriage and camp equipage had netted upwards of £35,000 on their successful campaign around the country. She later acquired them for her own exhibition.

On tour, Marie realized that royal news was a big draw, and the British royal family started to become a useful source of revenue for her, through her illustrated news service. Her touring years coincided with a prolonged public-relations crisis for the Crown that she now turned to her advantage. Although the heart of her exhibition was the French material, and the French royal family, from 1809 she started to incorporate the British royals. The Hanoverians provided her with plenty of scope. Madness, adultery and corruption all tarnished the sceptre of monarchy. While George III, regarded as the ‘father of his people’, was an increasingly sad, frail figure–the Lear-like ranting having quietened in his final decade to a more docile detachment from reality–the love and pity he inspired in his frail old age were in direct opposition to the derision in which his sons were held. The Duke of Wellington described George IV and his brothers as ‘the damnedest millstones about the neck of any government that can ever be imagined’.

The heir to the throne was held in particularly strong contempt. Gluttonous, adulterous, envious and slothful, the Prince Regent indulged in almost the full quota of deadly sins. The Tsar of Russia’s sister described his wandering eyes as having ‘a brazen way of looking where eyes should not go’. And with sex went shopping: he didn’t blink at splurging £33 on milk of roses and scented powder for his toilette. Though his profligacy disgusted his subjects, the British people loved his wife, Caroline, Princess of Wales–who many, especially her husband, wished would spend both more money and more time on personal grooming. The Princess, who skimped on washing and changing her clothes, quite simply stank, and badly needed a dab of her husband’s expensive colognes. A diplomatic aide of the Prince had taken her aside: ‘I observed that a long toilette was necessary and gave her no credit for boasting that hers was a short one.’ If there was plenty of dirty linen in the royal household, there were vast quantities of dirty laundry in the public domain. The private life of Princess Caroline and the misdemeanours of Mary Anne Clark, the mistress of the Regent’s brother, the Duke of York, were but two of the most popular topics of royal gossip, and Marie’s figures turned both women into a new form of talking point.

Mary Anne Clark topped the bill in Marie’s exhibition when she was catapulted to national interest by claims that she had been using her position to advance the military career of any ambitious soldier who would pay her enough to further his cause. Corruption in the corridors of power is always of public interest, but when it moves to the bedrooms of power it takes on a different piquancy. The love letters between the Duke and his mistress were produced in the public inquiry held at the House of Commons, and as the investigation unfolded the nation was transfixed. As well as their printed intimacies, lovey-dovey exchanges overheard by their domestic staff were all considered as evidence of the Duke’s collaboration in his lover’s scheme. It was said that, while the case continued, children in the streets took to shouting ‘Duke’ or ‘Darling’ instead of ‘Heads’ or ‘Tails’ when they flipped coins. Although cleared, the grand old Duke of York’s military career, immortalized in the nursery rhyme, came to an abrupt end. The professional credibility of the man who had famously commanded ten thousand men was irreparably damaged by his middle-aged mercenary mistress, who, over and above the promotions she traded in on behalf of others, through fast-track self-promotion had graduated from marriage to a stonemason to the bedroom of the second in line to the throne.

The second major scandal from which Marie profited was the sensational inquiry into the alleged adultery of Princess Caroline, the estranged wife of the Prince Regent (later George IV), with a flamboyant Italian called Bergami. When George III finally died, the problem for his son and heir was that the wife he loathed was legitimately the Queen and officially entitled to be at his side. The so-called Milan Commission arose from his hopes that she would be deemed unfit for queenly office. From her enforced exile abroad, bulletins about Caroline and Bergami shocked and amused in equal measure. There were stories of them canoodling in a pink seashell chariot pulled by horses through the streets of Milan, with her by now a fleshy fifty-something in a low-cut gown, her acres of pink satin billowing and bulging in the arms of her svelte suitor. But not even the news of their absurd entry on donkeys into Jerusalem, where she had founded an honorary order of knights in Bergami’s name, diminished her in the affections of the English people. A big headache for the King was that the public preferred his wife. They booed him and cheered her. It was in part the fear of the crowd that informed the decision to abandon the inquiry and simply to sideline the Queen, albeit unofficially. The strength of public regard for her was perceived as potentially inflammatory.

The findings of the Milan Commission were fed to a Secret Committee of the House of Lords, and under the terms of a private bill the Queen was put on trial. Talk of the contents of a green bag containing the most incriminating evidence against her gripped the nation and inspired cartoons and lampoons ad infinitum. This sensational marital showdown dominated 1820, and while it did Marie ensured her figure of Bergami was in pride of place in her exhibition. For example, in July 1820 the Manchester Herald reported on the inclusion of ‘Bartholemew Bergami–a figure of this so much talked about character, who was so suddenly raised from the situation of a menial to the rank of Noble, by the partiality of a Princess, is now added to the splendid and interesting collection of Madame Tussaud.’ In October the public were still fascinated: ‘Bergami–as this celebrated Italian will this day become the subject of the House of Lords, so we suppose that on this day, and every day and night this week, the crowds will resort to the Exchange dining room to see his astonishing accurate likeness.’ Eventually the case against the Queen was abandoned, but she was banned from attending the coronation. The King never could see what the public saw in his wife. It is said that when an equerry informing him of Napoleon’s death said, ‘Sire, your greatest enemy is dead,’ the King replied, ‘By gad, is she!’

There was an interesting duality to Marie’s presentation of royal material. She catered to public interest by giving pride of place to the most talked-about protagonists in each new royal scandal as and when it became of national interest. But she also started to manipulate public opinion by replacing the flawed reality of the royal family as individuals by a bigger image of sovereignty that tapped into notions of national identity, the displayed scarlet and ermine of state evoking the dignified grandeur of heritage and history. Marie did George IV a particularly good service: her wax image was far more regal than the unmajestic figure he cut in real life–stout and gouty, and increasingly reliant on greasepaint and false whiskers to disguise his ruddy, hung-over face. The English-born Irish novelist Maria Edgeworth said that even when the King was well ‘He looked like a great sausage, stuffed into the covering.’

The coronation tableaux that Marie developed on tour were particularly popular, and became the basis of a segment of the exhibition that would enjoy lasting success in London. The tableau she introduced in 1821 was but one form of representation of the coronation, for there were also competing models, panoramas and, most striking, theatrical performances. In Liverpool, in December 1821, Marie was in direct competition with Mr Coleman’s nightly performance of ‘the superb spectacle’, which was on such a scale that in addition to the regular theatre troupe there were 200 extras. That an event which represented a solemn sacrament in the eyes of the Church was re-enacted as a play, and in Marie’s case was depicted on the same premises as the heads of criminals, highlights a hunger for information that is today satisfied by extensive reporting and television coverage. Bearing in mind the controversy surrounding the televising of the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, when eminent figures argued that the ceremony ran the risk of being demeaned by being watched in a public house, it is interesting to consider whether these mock-ups succeeded in bringing the public closer to a solemn rite or whether they trivialized it. In fact Marie and Mr Coleman’s versions were probably more dignified than the real thing, for according to some of those who had a bird’s-eye view of the real coronation the King himself trivialized the occasion. Mrs Arbuthnot complained that he behaved ‘very indecently’, and the Duke of Wellington noted, ‘soft eyes, kisses given on rings which everyone observed’. A year later Messrs Rundell, Bridge & Co. were still owed £33,000 for the regalia they had supplied. Marie’s own throne-fitters, Messrs Petrie and Walker of St Ann’s Street, had long since been paid.

Marie’s advertisements in the Liverpool and Manchester press chart the development of her coronation crowd-puller. The earliest version, in Liverpool in July 1821 (the same week as the real event), focused on ‘the superb figure of His Majesty, on which no exertions have been spared to render it worthy of being considered a correct representation of the Illustrious Person on whom the crown now sits’. In the evenings the King’s subjects could admire his likeness while a full military band played in the background. A few months later, in Manchester, she placed the King in a more elaborate setting and ‘completely transformed the Golden Lion Assembly Room into a representation of the magnificent throne room in Carlton-Palace’. The reviews were ecstatic: ‘The coronation group which is now exhibited to the public in the Exchange Room, exceeds anything of the kind ever exhibited in this town,’ gushed the Manchester Guardian. Another paper enthused, ‘It gives such an air of reality to the scene that respect and deference is conjured up the moment the eye rests upon this imposing spectacle.’

This splendid coup d’œil proved so popular that Marie, knowing she was on to a good thing, continued to expand and adapt it, adding allegorical figures of Britannia, Hibernia and Caledonia. The public loved it. ‘He nearly looks a king; we felt not a little proud, when we looked at our sovereign,’ the Blackburn Mail declared in April 1822. Spurred by such acclaim, Marie introduced a new dimension of piquancy by creating a dramatic double bill in which the ‘august coronation of his most gracious majesty George IV’ was juxtaposed with the coronation of Bonaparte. The spice of legitimacy versus illegitimacy in claimants to a throne was a brilliant piece of showmanship.

Always mindful of the need for change, in order to maintain interest and justify return visits, she then introduced historical figures of the Kings and Queens of England, allowing the public ‘to walk along the plank of time’ as one review put it. This duality of hot news and history that she tried out on the road, blending the sensational in the present with the pageantry of the past, was a prototype of a format that she was able to expand upon greatly when her show finally came to a halt in fixed premises. By the time it did, the life of the third English king whose reign she had lived under, and whose features she had cast, was coming to a close.

Man inspecting ‘Monster Alligator’, drawing by George Scharf