16

Bringing the Gods Down to Earth

MARIE DID NOT merely chart the fame of others: in the final phase of her life she herself attained a new level of recognition in the public arena. Publication of her memoirs, immortalization by Dickens, the commissioning of her portrait by Paul Fischer (whose other subjects included members of the royal family) and a famous Cruikshank cartoon, ‘I dreamt that I slept at Madame Tussaud’s’, helped to increase her public stature. References to her on the London stage, songs such as ‘Madame Tussaud’s, or a Row Amongst the Figures’, and an almost perpetual presence in the pages of the press–most frequently in the new generation of illustrated periodicals–all paved the path to her becoming a national institution.

She herself was the focus of public interest and increasingly identified with the exhibition, while her large family unobtrusively assumed their place in the wealthy middle class. They dwelt in self-consciously impressive suburban splendour, but lived for their work. Joseph and Francis provided their children with expensive educations in unquestioned preparation for them to join the family business, with the aim of furthering the fortunes of an entrepreneurial dynasty that was already outstandingly successful by the time Marie died. They were upright members of society and supporters of good causes–including the temperance movement–and they inspired loyalty in the few employees who were not family members. How proud Marie must have been when in 1847 her sons became naturalized British citizens, with the sponsorship of Admiral Napier, the MP for Marylebone, a distinguished naval officer whose wax figure was on display. This was a ringing endorsement of the family’s respectability.

An undated family group in silhouette, made by Joseph, has them standing apart in a formal arrangement, with Elizabeth, his wife, in the centre playing a harp, as Francis looks on, the tailoring of his frock coat lending him elegance. But it is not him as the paterfamilias figure who is the kingpin of the piece: it is the redoubtable matriarch on the left-hand side, a small well-rounded figure in her trademark bonnet and lace collars, her hand extending an exhibition catalogue to a graceful woman–possibly her other daughter-in-law, Rebecca. Silhouettes use darkness for definition, and so it is with the family. There is virtually no material that allows us to penetrate their private lives. Even in this picture the background drapery, pedestals and bust of Napoleon suggest the interior of the exhibition; even this is not the family at home. We only ever see them in the outline of their public achievement–especially Marie, who, approaching her eighties, showed no sign of relinquishing her control of the business.

Before the family photograph album: silhouettes by Joseph Tussaud

Fortunately we have a good eyewitness description of what she looked like in her London years from Joseph Mead, author/publisher of London Interiors: ‘She possesses a small and delicate person, neat and well-developed features; eyes apparently superior to the use of a pair of lazy spectacles, which enjoy a graceful sinecure upon her nose’s tip. Line upon line, faintly, but clearly drawn, display upon her forehead all the parallels of life. Her manner is easy and self possessed and were she motionless, you would take her to be a waxwork.’ Age did not dim her eye for business, and, from improvements and additions to advertising, nothing in the day-to-day running of the exhibition happened without her sanction. Her sprightly manner was remarked on by the London Saturday Journal: ‘Though nearly 80 years of age, being born in 1760 [Marie, whether forgetfully or not, always gave the wrong year for her birth], she does not look more than 65 and bids fair in this respect to rival her maternal ancestors who she tells us were remarkable for their longevity.’

She made a lasting impression on visitors. Enveloped in what one of them called ‘her veritable black silk cloak and bonnet’, bespectacled and sitting from dawn until dusk at the cash desk with a pile of catalogues by her side, she became part of the exhibition, a permanent display. She was the first person whom people encountered when they came to the anteroom at the top of the stairs.

An American visitor whose recollections were published in a memoir, What I Saw in London, wrote:

We entered the saloon in Baker Street through a beautiful hall richly adorned with antique casts and modern sculptures, passed up a flight of stairs magnificent with arabesques, artificial flowers and large mirrors and halted at the entrance door to deposit our fee into the hands of the veritable Madame Tussaud herself, who sat in an armchair by the entrance as motionless as one of her own wax figures. It was well worth the shilling just to see her.

Another visitor reported, ‘Here sat the venerable Madame Tussaud herself, at the receipt of custom. Having paid our shilling she beckoned to a door of a looking glass and on opening it what a sight presented itself. Figures of the size of life, of all ages and of all countries were grouped about the room–some of them of such intense resemblance to life as to be quite startling.’ Another visitor recalled her ‘bowing to the company as they came in and out’.

Elsewhere it was her conversation that was remembered, accented in a distinctive Germanic-Gallic mix. She never spoke more than broken English. Before her memoirs came out, many people commented on the fact that ‘Madame Tussaud often talked about her life in France.’ The stories of her life at Versailles, teaching Madame Elizabeth, her time in the Terror and meeting Napoleon were all trotted out. The claims she made in conversations with visitors to the exhibition percolated into the papers. A Times reporter recalled her account of how Curtius and she had been resident in Paris during the horror of the Revolution and, ‘as the lady herself declares, employed by the authorities of those days to make many of the likenesses now exhibited’.

The London where Marie was nearing the end of her life was frantic with change and unrecognizable from the city she had left to embark on her travels all those years ago. Gaslight and gilding, acres of glass, particularly in the showrooms of shops, all vied to attract consumers. These changes did not go unremarked by the press. In ‘A Paper on Puffing [i.e. advertising]’, an anonymous writer for Ainsworth’s Magazine of July 1842 asked, ‘Is the transition from the barber’s pole to the revolving bust of the perruquier, nothing?–The leap from the bare counter-traversed shop to the carpeted and mirrored saloon of trade nothing? Are they not, one and all, practical puffs intended to invest commerce with elegance and to throw a halo round extravagance?’

In Past and Present, in 1843, Thomas Carlyle railed against the rise of advertising:

The Hatter in the Strand of London, instead of making better felt-hats than another, mounts a huge lath-and-plaster Hat, seven-feet high, upon wheels; sends a man to drive it through the streets; hoping to be saved thereby. He has not attempted to make better hats, as he was appointed by the Universe to do, and as with this ingenuity of his he could very probably have done; but his whole industry is turned to persuade us that he has made such. He too knows that the Quack has become God.

As the art of selling became more sophisticated, Victorian advertisers rose to the challenge. The tailors Moses and Sons took copywriting to new heights: ‘When ever I’m in want of dress, I always buy at M&S.’ Others took a more literary approach:

To eat or not to eat,

That is the Question.

Whether ’tis better to be unprovided at routs,

Assemblies or pleasure parties,

Or to obtain Hickson’s Prepared Anchovies

And have the choicest sandwich.

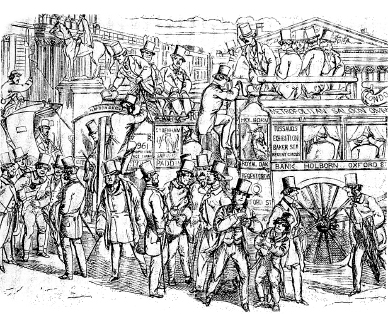

If culverts and cuttings for the railway were disfiguring great chunks of London, other defacements were to be found on walls. Because taxes on newspaper advertising were still prohibitively high, handbills and posters were the preferred medium for those wanting to promote their wares. Advertising mania became a pet topic in Punch: ‘They are covering all the bridges now with bills and placards. They will be turning the bed of the river next into a series of four-posters.’ It was as if Marie was being caught up with, for she had always advertised heavily. Her advertisements were among the first to adorn the sides of London’s first mass-transit service, Shillibeer’s horse-drawn omnibuses, and a sign of her prolific publicity is that in prints of the streets of London from this period you can nearly always discern her name on heavily covered walls. From giant hats and balloon bombardment of flyers to sandwich men and bill-stickers, more attention than ever was being paid to publicity, and London in particular was in the grip of an aggressive advertising boom.

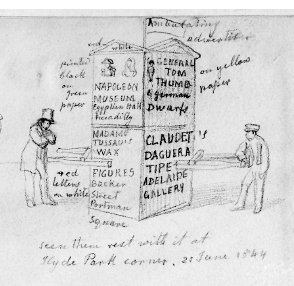

‘The Ambulatory Advertiser’, drawing by George Scharf

As Marie was slowing down, life around her seemed to be speeding up. Society seemed to be hurtling towards the future. The accelerated rate of technological innovations affected the mobility of people, things, information and ideas, and all these developments were a catalyst for radical developments in how people enjoyed themselves, and the forms their pleasures took. With the penny post, penny-a-mile travel by third-class rail, and the proliferation of affordable reading matter, there was a growing bank of shared information.

Regional differences began to dwindle, traditional class barriers weakened, and a common cultural frame of reference emerged–substantially as a result of the rise of the press, but also influenced by popular fiction, the most influential mass medium of the Victorian age. Dickens had blazed the trail in this regard. In 1847, writing on Dickens’s fame, a contemporary noted, ‘It started into a celebrity, which for its extraordinary influence upon social feelings and even political institutions and for the strength of regard and even warm personal attachment by which it has been accompanied all over the world, we believe is without parallel in the history of letters.’ Thackeray also enjoyed the fruits of fame, writing to Lady Blessington, ‘I reel from dinner party to dinner party. I wallow in turtle and swim in claret and shampang [sic]’.

Paradoxically, the more homogenised culture became, the more the cult of admiration for specific individuals grew, and there was also a more effective network through which to share the communal abhorrence of and fascination with murderers. Marie harnessed these currents of change to her own advantage and, pandering to an emerging mass market, rose in old age to the heights of her renown.

The cult of admiration was a by-product of an increasingly self-conscious society in which preoccupation with how one appeared in public was accompanied by a new interest in the status achieved by others. People held in high regard began to play a role in consumerism. To start with, aristocrats and clergy were the unlikely promoters of products in the pages of periodicals. The long list of named patrons recommending Mr Cockle’s Antibilious Pills included ten dukes, five marquises and an archbishop; the ‘many persons of rank and fortune’ who corroborated the benefits of the British Antisyphilis treatment understandably preferred to remain anonymous. Gradually, from the nobility and gentry being the principal endorsers, other notable people became a source of personal recommendations.

In 1845 Marie herself featured in a celebrity endorsement of a health-giving tonic, promoted as curing an impressive list of ailments, including Indigestion, Flatulence, Head Ache produced by Indigestion, Sickness, Dropsy, Fits and Spasms (a sure cure in three minutes): ‘Madame Tussaud of Baker Street, Portman Square, has much pleasure in giving testimony to the great benefit she has received by taking the Elixir Sans Pareil during the last seven years.’ Elsewhere she endorsed a firm of dyers.

The greater use of famous people to sell a vast range of consumer goods is reflected in Marie’s own catalogue, which by 1844 had a circulation of 8,000 copies a quarter, rising to 10,000 three years later. Her ‘biographical sketches’ are flanked by advertisements. Amid the endless ads for Ventilating Hats and Invisible Hair are notices for Nelson’s Gelatine, Royal Victoria Carpet Felting, Albert Cravats and the Wellington Surtout, a ‘new, light, repellent overcoat for all seasons’. Elsewhere, Napoleon was being used to promote various products including shoe blacking and ink, and the showman–strongman–explorer Belzoni, endorsed hair dye (perhaps exploiting the link between Samson and hair). Less flattering product association was that posthumously foisted on William Cobbett: ‘In his Register for June 1832 the late William Cobbett MP described the suffering he had endured for 22 years from the use of imperfect trusses.’ Relief could have been supplied by Mr Cole’s patented improved product. Technological advances in printing meant that for the first time celebrity likenesses were used on pre-packaged foods for the mass market, on pot lids for such products as relish, meat paste and sauces. The Duke of Wellington and Sir Robert Peel were all used in this way, and even Prince Albert’s face appeared on tubs of shaving cream.

One can see very clearly the scaffolding of celebrity culture in the midst of which Marie was proving herself a talented architect. The dissemination of information about public figures in print was the first step, followed by dissemination of their pictorial likenesses. Carte de visite mania, the craze for collecting small photographic portraits of the famous, happened after Marie’s death, but in her lifetime photography–or ‘drawing by light’–was in fits and starts attempting to close the gap between original and copy. In an 1842 trade magazine an advertisement for Madame Tussaud’s exhibition appears beside one promoting photography–at this time still being marketed as an aid for artists: ‘By this process the artist will derive great advantage in having a perfectly accurate likeness, from which he can paint a portrait, saving much of his own time and trouble as well as the time of his sitter.’ While the photographic process was much improved during her lifetime, it was not until the decade immediately after her death that the commercial scope of the genre was realized.

Last but not least in the nascent cult of celebrity was the impact of mass-produced figurines. From 1843 to 1850 the growing popularity of non-royal civilian likenesses at the waxworks was mirrored by figurines of people from all walks of life–entertainers, certain popular clergymen, and statesmen such as Wellington and Peel–becoming the must-have home accessory to place on the pianoforte, somewhere near the aspidistra. The Staffordshire potteries were but one producer which profited from this boom, and one of their best-sellers was Jenny Lind. Known as the ‘Swedish Nightingale’, she was one of the first entertainers to experience a mob of fans. She made her London debut in 1847, and became a favourite with the Queen. She exemplifies the advent of the celebrity as a mass-market phenomenon crossing the class divide, and naturally her likeness was installed at Baker Street. As a magazine called The Era put it, ‘The queen in her palace, the lady in her boudoir, the men at their clubs, the merchant on the change, the clerk in his office, and indeed all sorts of people from the most exalted to the lowest members of society spoke of Jenny Lind.’ Naturally her name was used by opportunist advertisers to promote goods–plausibly in the case of street ballads, but less so when it came to men’s clothes. Lind hinted at a new star power that would eventually drive the aristocrats out of the ads.

One of many lessons learned at Curtius’s knee was that crime paid, and the dividends for Marie and her family were particularly good in 1849 when two murder stories were national sensations. On 21 April James Blomfield Rush was executed at Norwich for the triple murder of his landlord and two members of his landlord’s family. Public interest was so intense that special trains were laid on for visitors to the crime scene. Later that year, on 13 November, an estimated 50,000 people attended the public execution in London of Maria Manning and her husband, George, for the murder of her lover, Patrick O’Connor, a retired customs officer. The sexual frisson of a ménage à trois was enhanced by titillating reports of Maria Manning’s tight-fitting black-satin dress–one paper said that the attention given to this ruined the satin industry for the next twenty years. But for Marie, watching from the wings, this was a boon. The wax figures took up their place in the Chamber of Horrors, which was permanently packed as a result of the voyeuristic interest. Punch once again launched a hostile attack on Madame Tussaud, who ‘displays the names of the Mannings and Rush as the manager of a theatre would parade the combination of two or three stars on the same evening’. The Art Journal also inveighed against the glamorization of crime: ‘Should such indecent additions continue to be made to this exhibition, the horrors of the collection will assuredly preponderate. It is painful to reflect that although there are noble and worthy characters really deserving of being immortalised in wax, these would have no chance in the scale of attention with a thrice-dyed miscreant.’ By way of defence, the Tussauds took to publishing the following apologia: ‘They assure the public that so far from the exhibition of the likenesses of criminals creating a desire to imitate them, Experience teaches them that it has a direct tendency to the contrary.’ They also decided on the back of the Mannings to expand their aversion therapy: ‘The sensation created by the crimes of Rush and the Mannings was so great that thousands were unable to satisfy their curiosity.’ The most telling aspect of the Victorian fascination with murder was the popularity of figurines of murderers and ceramic models of the crime scenes, at a time when Victoria’s brood of rosy-cheeked princes and princesses inspired no Staffordshire portraits and comparatively few prints. Cheap accounts of murders also enjoyed a circulation of millions when national newspaper circulation was still hovering around a hundred thousand.

By questioning the status of kings as divine rulers, in the Paris of her early life the philosophers whom Marie described as family friends had set in train a process that would see the world transformed before she died. As kings and queens were demystified, they became more like the servants, not the rulers, of their subjects. Marie’s wax exhibition documents a power shift from the subservience of the subject to the dominance of the fan. The last major tableau of the royal family that Marie herself lived to see installed was entitled ‘Sweet Home’, after ‘Home, Sweet Home’, a song that had greatest-hit status in the nineteenth century, selling over 100,000 copies in sheet-music form in its first year alone. It was like a theme song for an era that celebrated domesticity. It was also a suitable caption for the wax group that represented Prince Albert and Victoria at home, ‘sitting on a magnificent sofa’ and ‘caressing their lovely children’. This image of family harmony was striking for its simple depiction of the royals as ordinary people–‘the whole intended to convey an idea of that sweet home for which every Englishman feels that love and respect which can but end with their lives’. For visitors, it was as if they had just been announced and entered the royal drawing room.

This family group was a radical view of monarchy, for it played on ideas of the royals’ similarity to those viewing them, not the distance which had been so forceful in, for example, that first crowd-pleasing wax tableau of the Grand Couvert of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. The ceremonial at Versailles had been intended to emphasize the distance between monarch and subject–as Sénac de Meilhan had said in Ancien Régime France, ‘It is good for the monarch to come close to his subject, but this needs to be through the exercise of sovereignty and not by the familiarity of social life. This familiarity allows too much to be seen of the man, and reduces respect for the monarch.’

It was as if very gradually the royal family were becoming an entertainment, like a family saga in one of the new mass-market inexpensive novels, of interest for their private life and personalities, and access to them in the private realm was increasingly regarded as a right. There was also a sense in which, as the royals became less regal, the middle classes subscribed with gusto to delusions of grandeur. While Victoria displayed her bourgeois taste in the style of her royal residences and convinced the public that her castles and palaces were primarily homes, the newly affluent sector of her subjects went on a frenzied buying spree to assert that the Englishman’s home was his castle.

The ‘Sweet Home’ tableau of the Royal Family was in sharp contrast to the other major installation that people continued to flock to see, which was the shrine of Napoleon. This juxtaposition highlights the forces of change that had coursed through Marie’s long life. For as the royal family seemed to become more ordinary, and were seen as similar to the public who were their subjects, individual achievers were increasingly seen as superior and different from the public who were their fans. This elevation of ordinary men into almost superhuman beings was exemplified by the cult of Napoleon. If deference for the royals was diminished, then there were quasi-religious connotations to the reverence with which the public filed past Napoleon’s toothbrush and blood-stained counterpane, and stood before one of his teeth (the catalogue said that during the extraction ‘the Emperor suffered much’). For Marie, Napoleon was one man who never let her down, and with whom she had a blissfully happy partnership that saw her through good times and bad, for richer and richer and richer until death did them part.

Napoleon’s carriage illustrates poster describing the collection in its prime, 1846

Napoleon was resurrected from death by the sheer volume of commercial entertainments that he featured in. Even his cancerous stomach, preserved like a saint’s relic and labelled as historical evidence of the cause of the great man’s death, could be seen at the Hunterian Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons, until a French visitor’s protest restored it to anonymity when the card identifying the controversial specimen was removed. Dickens reported the fracas when the imperial relic was spotted: ‘“Perfide Albion!” shrieked a wild Gaul whose enthusiasm seemed as though it had been fed on Cognac. “Perfide Albion!” again and more loudly rang through the usually quiet hall. “Not sufficient to have your Vaterloo Bridge, your Vaterloo Place, your Vaterloo boots, but you put violent hands on the grand Emperor himself.”…From that time the pathological record of Napoleon’s fatal malady has been unnumbered and–to the millions–unrecognisable.’ Doing the rounds elsewhere was a wax likeness of the emperor with mechanical lungs. The publicity posters screamed, ‘Napoleon is not Dead! You may see and hear the phenomenon of respiration, feel the softness of the skin and the elasticity of the flesh, the existence of the bones, and the entire structure of the body.’

Increasingly there was a sense of entitlement to access to information about figures in public life. How telling that in the final years of Marie’s life Victoria and Albert took legal action in an unprecedented way as a result of infringement of their privacy when family etchings were reproduced without their knowledge for the commercial market. That was a whisper of what would become amplified many times over in the next century, when there would be virtually no escape from the lens and the click that could make a million copies of a private moment. The press that Dickens satirized in Martin Chuzzlewit–‘Here’s this morning’s New York Sewer!…Here’s this morning’s New York Stabber! Here’s the New York Family Spy! Here’s the New York Private Listener!…Here’s the New York Keyhole Reporter’–was both a nightmare and a prophesy.

A pertinent comment on our present-day relationship to the stars was made in a book about American cinema by Margaret Thorp, who said, ‘[The] desire to bring the stars down to earth is one of the trends of the times.’ If gods are substituted for stars, then the statement fits Marie’s achievement: she helped to bring the gods of her day down to earth. These gods were first of all the royals, and Establishment figures: then they diversified to include entertainers and performers, anticipating current attitudes. Now we don’t want merely to bring the stars down to earth, but to wear the same trainers as they do. Some fans treat their bodies as temples to the various stars they revere, eating and drinking the same foods, carrying the same bags. The first stirrings of consumer imitation were happening in Marie’s last years.

Her primitive form of virtual reality has entertained without pause for a great many years, and for this alone she deserves far more credit than she has received to date. In so much of what she did can be seen the faint outlines of phenomena that are immense today, and her life remains highly relevant to how we live now, illuminating and reflecting aspects of human nature that are unchanged. In the twenty-first century it is said that if you ask the average teenager what they want to be the reply is ‘Famous.’ But the craving for renown was evident as early as 1843, an article in the Edinburgh Review makes clear:

In short there is no disguising it, the grand principle of modern existence is notoriety; we live and move and have our being in print. What Curran said of Byron, that ‘he wept for the press and wiped his eyes with the public,’ may now be predicated of everyone who is striving for any sort of distinction. He must not only weep, but eat, drink, walk, talk, hunt, shoot, give parties and travel in the newspapers. The universal inference is that if a man be not known he cannot be worth knowing. In this state of things it is useless to swim against the stream, and folly to differ from our contemporaries; a prudent youth will purchase the last edition of ‘The Art of Rising in the World’, or ‘Every Man his own Fortune-maker’, and sedulously practise the main precept it enjoys–never to omit an opportunity of placing your name in printed characters before the world.

But Marie’s life also shows us how we have changed. Hers was a labour-intensive as well as artistically complex way of rendering likeness. People enjoyed the results communally, in person. Today ubiquitous camera lenses make instant likenesses for consumption by a global anonymous audience. She lived on the cusp of the coming of photography that Baudelaire felt was sacrilegious, as he witnessed society ‘rushing as one Narcissus to contemplate its own trivial image in the plate’. Fascination with our own likeness became bound up with changes in the expression and focus of our regard for others. Instead of the solidity of bronze and marble, wax, print and photographs are more fitting media for our more ephemeral allegiances. On two days in 1843, 100,000 people queued to see Nelson’s colossal statue when it was on the ground, before it was erected on its giant plinth in Trafalgar Square and that is the biggest difference. Marie’s audience still lived in the shade of heroes, whereas we live dazzled by the glare of celebrities, and measure fame in column inches.

Until shortly before she died, in her ninetieth year, Marie was frail but healthy. She had a remarkable constitution. Well into her eighties, she was described as ‘as hale to appearance as when at the command of the National Convention she took the portraits in wax from the faces of Hébert, Robespierre and the other heroes of the Reign of Terror which now figure in what she calls her Chamber of Horrors’. As meticulous a housekeeper as she was accountant, she would often personally inspect the linen and lace on the figures to ensure that they were well turned out. She remained, if not a front-of-house presence, an important force backstage, and was certainly party to the proposed expansion of the exhibition in readiness for the Great Exhibition of 1851, for which planning had already begun in earnest. Asthma had been a weakness, but old age was the reason her lungs finally stopped breathing on Monday 15 April 1850. A perfect copperplate hand recorded in the ledger, ‘Madame Died.’

When she was still a novice with a lot to learn, she had been so excited when in Edinburgh, with the ambitious entry fee of two shillings, she had taken £314s on her first day. Advertising then was mainly a matter of handbills. In the week that she died, 800 copies of the catalogue were sold, and takings were £199 9s., despite the exhibition being closed on the day of her funeral, the Friday. Advertising now spanned twelve newspapers and–indicative of interest in train tourists–railway guides. Marie’s own journey from the Boulevard du Temple to the comfortable surroundings of 58 Baker Street (the address given on her death certificate) had been pretty epic: two countries, hundreds of towns and cities, the drama of near-death, human disappointments. The woman who had arrived with a few packing cases and moulds nearly fifty years earlier, and fretted about her young sons’ security, was leaving a priceless collection, a world-famous landmark that meant Messrs Tussaud were set fair for the future.

Beyond her material legacy, prestigious proof of her achievement was evident in numerous obituaries in the national press, including The Times, the Pall Mall Gazette and the Illustrated London News, which also published an engraving. Given the taint of institutional prejudices at this time these were notable laurels. The pages of the Illustrated London News tended to be stiff with titled men, people whose family trees had long and royal roots–les vieilles riches–and dusty clerics like Reverend Casaubon. That a waxwork proprietor, let alone a woman with a French background and a long history of travelling with a commercial exhibition, and all without a husband, should be included in the pages entitled Eminent Persons Recently Deceased was a substantial form of acknowledgement.

Many tributes, including that in the Annual Register, reproduced the biographical details that Marie had always fed her public. But as well as Madame Elizabeth, her class of pupils now included ‘the children of Louis and Marie Antoinette’. Apart from this, there were the usual repertoire of Ancien Régime and Revolutionary anecdotes, including her imprisonment with Joséphine and, of course, the heads: readers were told how ‘she had been employed to cast or model the guillotined heads of those she had known or loved, or those whom she had detested.’

But somehow, notwithstanding all the attention she received, acceptance of her exhibition was never quite there. While money had given her muscle, which she had flexed with serious investments and acquisitions for the business, her mass-market success had mired her for cultural purists. The rising tide of information from print, pictures and travel was for many people a peril. Packaging knowledge into forms that were particularly popular with the expanding middle class had been Madame Tussaud’s aim and achievement, but many were dismissive. She still suffers from the snob’s sneer. This prejudice is evident in ‘a visit to Madame Tussaud’s’ as written for the Illustrated Family Newspaper in 1854: ‘During a late sojourn in London, one of my first expeditions was to Madame Tussaud’s, a place that everybody sees, or has seen, but which nevertheless it is the fashion in London to laugh at, as being the delight and resort of all the wonder-seeking, horror-loving country bumpkins who visit town.’

Something of the same ambivalence resonates in the initial response to one of the greatest hits for the Tussauds, a painting they commissioned from Sir George Hayter in 1852: The Duke of Wellington Visiting the Effigy and Personal Relics of Napoleon. This representation of the greatest living Englishman contemplating up close the greatest dead Frenchman (whom many Victorians thought the greatest man the world has ever seen) was a sensational success. But the Illustrated London News qualified its praise:

At first the notion of associating the greatest living man of his age with an exhibition of waxwork may savour of somewhat questionable taste; but when we recollect that it was the only mode by which the two generals, historically connected as they were, could be brought together upon canvas, and when we know that the incident so embodied was one of actual occurrence, the force of prejudice on this point is weakened.

The longer Madame Tussaud’s was around, and the more popular it became, the more the gulf between a worthy gallery visit and fun at Tussaud;s widened in people’s minds. Thackeray conveys this succinctly in his novel The Newcomes, describing his visitors’ reaction to the sights of London: ‘For pictures they do not seem to care much; they thought the National Gallery a dreary exhibition, and in the Royal Academy could be got to admire nothing but the picture of ‘M’collop of M’collop’ by our friend of the like name; but Madame Tussaud’s interesting exhibition of waxwork they thought to be the most delightful in London.’

But off the pages of novels, in life, Madame Tussaud’s left some people cold. The American visitor Benjamin Moran was unimpressed: ‘So much for Madam Tussaud’s exhibition of wax figures, the resort of the curious, and a sham to please or alarm. It is without misrepresentation, the most abominable abomination in the great city, and the very audience hall of humbugs. Barnum ought to have it.’

It seems more than a little ironic that on Marie’s death certificate, dated 18 April 1850, under ‘Occupation’ is stated, ‘Widow of François Tussaud’. Even in death she was shadowed by a man whose sole contribution to her signified no real giving at all. The funeral took place a few days later at the Roman Catholic chapel at the corner of Cadogan Gardens and Pavilion Road in Chelsea. One imagines plumed horses and a sufficient display of black bombazine and sombre trappings to convey just the right amount of respect, neither too ostentatious nor too frugal to put in question the family’s solid middle-class propriety. It is somehow fitting with this maddeningly elusive dynasty that missing from the public domain are any references at all to Marie’s passing other than funeral costs. Figures not feelings. Sixty-three pounds, four shillings and sixpence covered mourning dress for staff, six black suits for male staff, four black silk bonnets and six grey straw (‘for domestics’), and an allowance for a cab for servants on the day of the funeral–all being itemised.

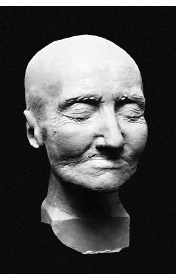

When Marie died, instead of their standard hangman’s harvest, it was their mother’s sunken features that Joseph and Francis had fixed in white plaster. The death mask survives. There is also an unobtrusive memorial tablet on the wall of St Mary’s Church near Sloane Square, the new Roman Catholic church to which her bones were removed, into a vault, when the old church was demolished: ‘Of your charity pray for the repose of the soul of Madame Marie Tussaud who departed this life April XV MDCCCL aged XC years, Requiescat in pace. Amen.’ But to get beneath the surface to the loves and hates, the foibles and fears of Madame Tussaud is another matter. All we have is fragments of character. But these reveal a strong one. According to a family anecdote told by her grandson Victor, Marie was persistently entreated by a neighbour in Portman Square to come and admire his own valuable art collection. Many people would have indulged an elderly man’s pride and even appreciated the opportunity for aesthetic reasons, but Marie is said to have dismissed him by saying that she never visited gentlemen, and when they visited her they always paid a shilling. More telling, she is also said to have rebuked Joseph for his tears when she was on her deathbed, and asked him if he was afraid to see an old woman die. Her aversion to lawyers was evident in the fact that she left no will, but instructed her sons to share everything. They had, of course, a formal partnership arrangement for the business.

Madame Tussaud’s death mask, by her sons

In some ways they were liberated when she died. She had apparently been a hard taskmistress, and, irrespective of the money coming in, practised life-long frugality. Victor Tussaud once wrote to his nephew about the fiscal rules that she insisted the family lived by:

It had been a veritable living from hand to mouth. Their system of business was peculiar, but sagacious. Such items for rent, gas, insurance were placed in reserve and accumulated weekly until due, and after paying wages and incidental expenses the balance if any, for sometimes there was none to divide, was divided by two, half being devoted towards improving attractions of their exhibition, however large their receipts, and consequent temptation to add to their private purses, and then the remainder to themselves in equal shares, which sometimes had been small indeed.

Striking in the different views that we do have of Madame Tussaud is the imagery of time and money. Victor recalled her daily ritual of winding and regulating ‘a dozen or more large silver watches’. Charles Dickens wrote, ‘The present writer remembers her well sitting at the entrance of her own show, and receiving the shillings which poured into her exchequer. She was evidently a person of a shrewd and strong character.’ This fed his portrayal of Mrs Jarley sitting ‘in the pay-place, chinking silver moneys from noon till night’ and entreating the crowd not to miss their chance to see her show before its imminent departure on a short tour among the crowned heads of Europe, positively fixed for the next week. ‘ “So be in time, be in time!” said Mrs Jarley at the close of every such address. “Remember that this is Jarley’s stupendous collection of upwards of One Hundred Figures, and that it is the only collection in the world; all others being impostors and deceptions. Be in time, be in time, be in time!” ’

This imagery is apt, because time and money were crucial to the might of the middle classes in Victorian England. The increase of these commodities was what determined the growth of the commercial entertainment sector that Madame Tussaud did so much to shape, and which was entering a new era when she died.