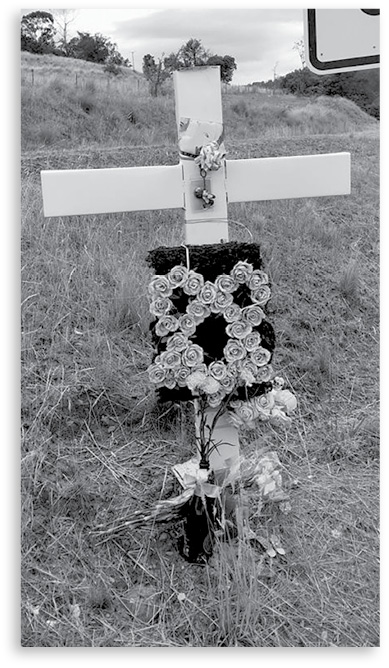

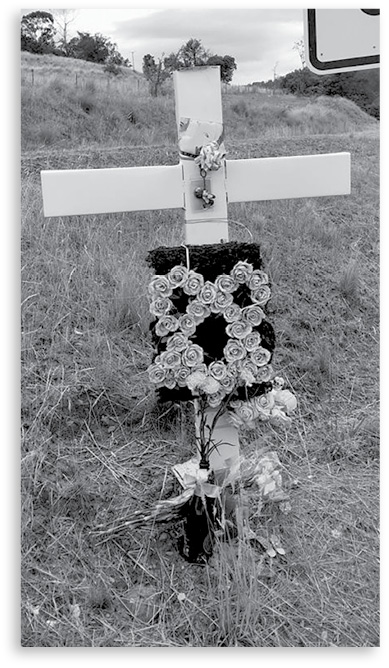

Roadside cross, erected and maintained by Natalia’s friends. marking the scene of the collision.

TWENTY-SIX SECONDS

Twenty-six seconds isn’t very long. It’s about the time it takes to put on a pair of shoes, boil a small amount of water, pick some herbs from the garden — or kill someone. Twenty-six seconds can be all it takes to snuff out a victim’s future, blighting the lives of those who survive.

At about 6.15 p.m. on 24 March 2013, a clear and sunny day, Natalia Dawn Pearn died as a result of injuries sustained in a crash between her car and a vehicle driven by Timothy James Ellis, on a straight stretch of Tasmania’s Midland Highway, near the gently named area known as Lovely Banks.

Natalia, 27, was returning home to Launceston after a weekend visit to friends in Hobart. She had been to visit friends, do a few complimentary hairdos for her mates, and buy some shoes.

In the other car were 57-year-old Tim Ellis, Tasmania’s Director of Public Prosecutions, and his wife, lawyer Anita Smith, who were returning to Hobart after a rare day socialising with their families in Longford and Legana and dropping off their dog to be looked after while they went on holiday.

Natalia was driving a small white Toyota hatchback, while Tim was steering a big dark-blue S-Class Mercedes, both travelling at about 100 km/h. When the vehicles collided, it was no contest.

This is Natalia’s story.

Natalia, the younger of two daughters of Alan and Kris Pearn, was born on 30 October 1985 and spent her childhood on the family farm at Whitemore, in northern Tasmania. Three generations of Pearns had farmed at Whitemore, which was one of the oldest farming settlements in the north. Alan and his brother ran the farm together, milking cows, running a few sheep, and growing crops. The farm also had a quarry, which had evolved into a landscaping and design business. All the businesses were run by family members — brothers and cousins of the third generation of Pearns.

Natalia was a funny little kid with tangled blonde hair and big blue eyes, always into everything. Alan remembers days when she’d come out on the tractor with him, and other days when she’d be sticky and dishevelled from playing outside. Family members remember her coming home grubby and smelling of lanolin from ‘helping’ with the shearing or crutching, chasing chooks and other livestock, or making mud pies.

Whitemore is a sleepy hamlet of about 300 people, with a small cluster of buildings on each side of the only road, surrounded by farming land. The nearest school required a trip by bus or car. When the girls reached school age, Alan broke with family tradition, sold his share of the farm to his brother, and relocated to Launceston, where he and Kris established their own business. Kris was a Launceston girl and had a close family network there, especially her sister and her sister’s daughter.

Natalia became very fashion-conscious as she grew up. Her big sister remembers that the girl who always had birds-nest hair because she didn’t like having it brushed turned into an adult who always looked ‘spot-on’.

She trained as a hairdresser, making many friends along the way. Always the life of the party, immersed in music, she matured into a beautiful, vivacious young woman, an award-winning hairdresser, a keen traveller, and a devoted daughter.

Natalia, known affectionately as Tali (or Tails) among her friends and family, decided to branch out and become independent. She left home and moved into a flat elsewhere in Launceston, establishing a vegie garden and getting a little white Chihuahua called Sugar. Emotionally, she was always close to her mum and dad, texting or ringing each morning about 6.30 a.m. (being former dairy farmers, they were all early risers). Her mum often babysat Sugar while Tali worked.

Tali planned trips overseas, encouraging her friends to follow her example and live life to the full. She’d say, ‘You never know what’s around the next corner, and you need to do things now.’

Tim Ellis, on the other hand, graduated in law from the University of Tasmania and became a partner at the respected Launceston law firm of Clarke and Gee, where he worked for 17 years, defending criminals all over the state and nationally. He was respected as a tough defence lawyer with a vast knowledge of the law and a habitual disdain for the prosecution’s case, with a degree of aggression thrown in. The courtroom’s a stage for barristers, and Tim played his part with gusto. He was well known to the police, who often came up against him as prosecutors or ‘informants’ in cases he was defending. Some liked him, others didn’t. All agreed he was a man not to be messed with.

As he grew into his public persona, he developed a reputation for being a tough litigator who was sometimes rude and aggressive. He was known to enjoy a drink or two when the court adjourned to the local watering hole after a long day. Having spent the day vigorously opposing (or even insulting) each other in court, he and his learned friends would chat together and swap stories in the pub afterwards. It’s a sight guaranteed to bewilder their clients, the parties involved in contested court cases. And Tasmania is a ‘boys’ club’ for lawyers. They all know each other and often share a drink after fiercely arguing for days in court.

Ellis became president of the Tasmanian Bar Association and was eventually appointed Tasmania’s second Director of Public Prosecutions in 1999, after Damian Bugg, the first DPP, was recruited to the Commonwealth Public Prosecutions office. Nationally, Australia has had a Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions since 1984, but the appointment of state Directors of Public Prosecutions is a relatively new practice. Each state and territory now has its own DPP. The role is very powerful, being second only to the Attorney General of the Commonwealth or state.

The DPP is supposed to be independent of government influence, even though the final authorisation for prosecutions rests with the elected Attorney General. In reality, the Attorney General takes advice from the office of the DPP and rarely refuses to prosecute against that advice. When the office of DPP was being created, it was seen as important to have a non-political figure acting on behalf of the state in running prosecutions. This separation of power also means that the DPP isn’t ‘hired and fired’ by a political party but is instead appointed by the Governor and can only be removed from office the same way.

At the time of his collision with Natalia Pearn, Tim Ellis had been Tasmania’s DPP for 19 years and wasn’t expected to relinquish that post until he turned 70. With an annual salary of about $500,000, one could say he was set for life. Or, if he followed the well-trodden paths of previous DPPs, he could expect to be appointed a judge for a few years before his retirement.

There is a common misconception that the Director of Public Prosecutions is out to get convictions in all the cases being tried. That isn’t strictly the case. The DPP represents the people in criminal cases and presents the case on behalf of the Commonwealth, state, or territory. The community’s interest is that the guilty be brought to justice and the innocent not be wrongly convicted. Sometimes an acquittal, rather than a conviction, may be a just outcome. The main function of the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions (ODPP) is to prosecute criminal matters at various levels, from occasional stints in the Magistrates Courts to the District, Supreme, and Mental Health Courts, the Court of Appeal, and the High Court of Australia.

The ODPP has a team of people, lawyers, police, forensic officers, and support staff to enable it to do its job.

On Sunday 24 March, Kris and Alan Pearn got a text message from Natalia around 4.30 p.m., saying she was leaving Hobart and would see them soon. She signed off, ‘I’m leaving. I’m coming home, Mumsy. I love you. And I love Dad too xxx’. The Pearns had recently sold their business and their house and had decided to move to the Gold Coast, which had been the scene of many happy family holidays while the girls were growing up. They’d purchased an attractive unit and would take on the role of managing 15 other luxury units in the same complex on the seafront at Surfers Paradise. They’d looked at bigger possibilities, but Alan said they were drawn by the sparkling blue of the pool at a complex called Villas de la Mer. The pool was about twice the size of those at the other units they’d considered, and it was the first thing they saw when they went in the front gate.

Their two daughters had been enthusiastic about the move and were looking forward to future Gold Coast holidays. Natalia had been planning a big farewell party for Thursday 28 March, with many friends and relatives coming to give Kris and Alan a send-off. Natalia loved a party, whether she was planning one or going to one, and she’d thrown herself into the preparations. Most of the packing was done, and the Pearns didn’t have a great deal on the agenda that Sunday night. They were just looking forward to seeing Tali and hearing about her weekend in Hobart.

Other key players in the drama that was about to eventuate were assembling from all over Tasmania. After lunch on the same Sunday, teacher Jane Bird, driving a government-issued white Subaru, left her home in Wynyard and headed along the coast to pick up her friend and fellow teacher Elizabeth (Beth) Murfett in Leith, northern Tasmania. They were travelling to Hobart to attend a conference next day. Jane said she’d drive to Campbell Town, where they agreed to stop for coffee and change drivers.

Driving out of Hobart at about the same time as Natalia were Richard Bowerman and his wife, Sarah, in a black Holden Commodore, pulling a trailer carrying his HQ Holden racing car. They were heading home to Rocherlea near Launceston, after Richard had spent the day competing in the car races at Baskerville. Richard said later that they’d finished early for a change and left about 5-ish. ‘We filled up at the BP and then headed up the Midland Highway.’

Sabina van Ingen also left Hobart for Launceston about 5.30 p.m., driving her husband in a navy-blue Toyota Echo. So did Greg Boyd, driving an Australia Post prime mover, pulling a 40-foot trailer.

In the historic town of Oatlands, which was once the halfway mark for travellers between Hobart and Launceston but is now bypassed by the highway, Sergeant Rob King was doing a solo shift in the sandstone police station, catching up on paperwork. Sundays are usually pretty uneventful in central Tasmania, apart from car crashes and the odd break-and-enter, and Rob was hoping for a quiet shift with no dramas. He would be disappointed.

In the police station at Bridgewater, closer to Hobart, Constables Susan Jenky and Tobias Schuumans were on afternoon shift, also hoping for a quiet stretch. They, too, would be disappointed.

And in Hobart itself, at the Office of Collision Investigation, Constable Kelly Cordwell was working on her collision-report files, hoping she wouldn’t be adding to them this weekend. Of all the police officers, she was the one most likely to be summoned to a collision, as she and her boss, Sergeant Rod Carrick, shared the responsibility for investigating crashes in the southern half of the state. She rarely enjoyed a quiet shift, and this would be no exception.

The volunteers of the State Emergency Service (SES) are trained to keep people safe in fires, floods, and other catastrophes. The SES in Oatlands is pretty active on fires and crashes, but they haven’t had a flood for a long time. Oatlands is a town where everyone knows everyone. The men on call that Sunday were ready for any emergency, with a fully equipped Ford Transit prepared for action and mobiles in their pockets.

All these people and more would have their peaceful Sundays shattered by the events that took place in twenty-six crucial seconds on the Midland Highway.

The Midland Highway used to be a narrow two-lane road, no wider than most suburban streets, with long stretches winding through scenic farmland. It was classic Tasmanian countryside, with green rolling paddocks filled with fat sheep and cows interspersed with little villages filled with sandstone cottages and old country pubs. The island’s English heritage was on view at every turn of the highway’s 170 kilometres, originally surveyed in 1807 by Surveyor-general Charles Grimes. Lachlan Macquarie, the governor of New South Wales, travelled the road on a visit with his wife Elizabeth in 1811.That journey took five and a half days.

In more recent times, there have been continuous upgrades, creating a wider carriageway and a network of overtaking lanes in both directions. Getting stuck on the winding road behind a semitrailer used to be a nightmare, but now the faster traffic can speed past. The upgrades have cut a three-hour drive in the 1970s to just under two hours now if you stick to the speed limit. The highway bypasses most of the towns, and all you see is rolling farmland dotted with farmhouses and outbuildings until you get to the historic hamlet of Campbell Town.

When Natalia set off from Hobart at about 5.30 p.m., she expected to be home in time for dinner. So did Richard Bowerman and Sabina van Ingen.

On the way south, Jane Bird and Beth Murfett stopped as planned in Campbell Town, visiting the bakery, where they had coffee and a cake to keep them going. Jane had driven about 200 kilometres of their 345-kilometre trip. The trip from Wynyard to Hobart is about four hours — not a long drive for a mainlander, but Tasmanians don’t usually travel long distances, and Jane was ready for a rest.

Further north, Tim Ellis’s large blue Mercedes was approaching Campbell Town, but he and Anita decided not to stop. They’d stopped on the way up and bought supplies for lunch at his parents’ Longford property, but Tim said he was tired of driving. He just wanted to get home, have a drink, and unwind after a long day. They were listening to some CDs, and Tim was occasionally breaking in to check the cricket score.

Jane and Beth had left to continue their journey before the Mercedes drove through the town. Quite a bit further south, they passed Sabina’s blue Toyota going in the opposite direction. Sabina had used the northbound overtaking lane to pass Richard Bowerman’s Commodore with its trailer, and she had moved back into the left-hand lane when she noticed something odd. In the northbound overtaking lane beside her was a large blue car driving in the wrong direction.

To reassure herself, she glanced at the ‘Keep left unless overtaking’ signs beside the road. She told me later, ‘I didn’t register quickly enough to flick my lights, but I just said to my husband, “He’s going to kill somebody” — because I knew that there were other cars behind that were slow, and that somebody would be overtaking.’ Sabina was past the blue Mercedes in a flash, but she was worried. She said, ‘I saw the driver for a second. He looked as if he was in a trance, sort of out of it.’ She didn’t register that it was Tim Ellis, although she actually knew him quite well.

Soon after, as she drove past the turnoff to Oatlands, a police car emerged from the side road, sirens on full. Sabina feared the worst.

Jane and Beth, travelling south, were also driving on the left-hand side of the road. They were approaching a long, sweeping right-hand bend near Lovely Banks when they saw a large Mercedes driving about 100 metres ahead of them, which then moved across from the left-hand lane into the middle lane, which was the overtaking lane for the northbound traffic.

‘There were no other vehicles to be overtaken,’ Jane told police later. ‘It was the only other vehicle in sight. There was absolutely nothing that I could see that would have made that manoeuvre necessary — no animal or any obstruction on the road.’

The big car continued driving south in the northbound overtaking lane for some distance ahead of them. Because of the long curve of the road ahead, it was impossible to see if anyone was coming from the south in the same overtaking lane. Jane felt a shiver of dread. ‘Beth, back off. Slow down a bit. He’s going to kill someone if he doesn’t pull over.’

They slowed to about 60 kilometres an hour. The Mercedes pulled ahead, then disappeared around the bend.

‘What is he doing?’ Jane and Beth asked each other.

It was a strange sight. The driver seemed to be in perfect control of his car, taking the bend easily, driving bang in the middle of the lane. It was just that the car was in the wrong lane. Jane said later, ‘At no point did it wobble or give any indication that someone was thinking twice about where they were.’

On the southern side of the sweeping bend, the highway inclined north into a hill, which slowed Richard’s Commodore with its heavy trailer. He’d recently been passed by a light-coloured car, which was probably Sabina’s, and then he saw a small white Toyota hatch pull out into the overtaking lane to pass him.

‘I was in the left-hand lane and obviously not the faster car on the road. You’ve got no rush with a trailer on,’ he said. ‘The white Corolla hatchback drove past doing barely the 110 mark, because I was doing under it — and it just cruised on slowly by, like it wasn’t in a rush, because anyone — you’re not in a rush to go home.’ He had no time to register if the driver was male or female.

Other than the driver of the Mercedes, Richard was the only eyewitness to the crash. His wife, Sarah, didn’t see anything because it all happened so quickly. When Richard described it a year later, he often lapsed into the present tense, showing it was still very immediate in his memory.

‘Her car is in its lane, maybe slightly to the right of its lane, but it’s a little car, so still well within the northbound overtaking lane, and then the dark-coloured car coming the other direction — I only saw that from the front, because it’s coming around the sweeping bend towards us slowly — well, the bend is slow sweeping — and then the dark-coloured car — it’s sideways spinning towards us …’

He said that when the two cars hit, the back wheels of the Mercedes seemed to lift off the ground at an angle between 35 and 45 degrees, and the Mercedes began to spin towards Richard’s car, pivoting somehow on its front wheels.

‘It’s then started scrolling around towards us,’ Richard said. ‘On the bounces, it got airborne and the back end was off the ground, and it started coming in our direction. I couldn’t tell you how many times it turned. At the time, it seemed like it was a couple of times it spun round. Stuff was flying off it everywhere — what looked like wiper blades, plastic trims, mirrors, pretty much anything that wasn’t anchored down hard enough.’

Richard said there was absolutely nothing he could do to avoid the approaching Mercedes. ‘As soon as I saw it, straightaway I’m on the brakes without trying to over-brake so the trailer goes ’round, and trying to keep it in a straight line, because there was nowhere else I could go. If you go out, you don’t know if there was other cars following him southbound, and you don’t know what’s behind you, so you can’t just swerve right, left, or anywhere.’

He said he just kept slowing down to minimise the combined speed of the inevitable impact, using every rally-driving skill he could muster. All his attention was on trying to avoid a head-on crash, or even a crash at all, but he had little chance given the trajectory of the Mercedes and the impossibility of swerving without endangering others or having his trailer jack-knife.

The next thing he remembers is a loud bang as the Mercedes hit his car. It collided slightly to the driver’s side of his car and the passenger side front of the Mercedes. Richard said, ‘The front passenger side headlight has collected just inside my headlight. So it’s almost head on but on an angle into the front, just inside the headlight into the radiator support, and then [it] dragged us both into the bank on the left-hand side of the road side by side.’ The two cars were jammed together, facing north, with Richard’s car in the deep gutter running alongside the road.

Richard’s next concern was for Sarah. She wasn’t hurt, even though their airbags didn’t operate, as she had been furthest from the impact. He was pretty pissed off at being hit, but she tried to calm his irritation, saying, ‘It’s not our fault. Let’s try to get out.’

Richard said, ‘I couldn’t get out my door because the doors were butted together, so I had to climb out over the seat and through the back passenger-side door to force Sarah’s door open.’

The collisions had happened by the time Beth and Jane drove round the bend a few seconds later.

‘Omigod!’ Jane said. ‘Pull over, Beth. Oh no!’

Jane told me, ‘We came around the corner, and the first thing we saw was a white car in the culvert on the right-hand side of the bend. We immediately realised that something had happened. And we noticed that the road was completely covered in debris. It was absolutely silent. No movement, no sound, just smoke coming from one of the cars.’

Beth said later, ‘When we rounded the bend it was just as if it had perhaps happened an hour ago. It was an eerie sight — the little white car, the Mercedes, the other vehicle that was sort of pushed in the side with a trailer on it. We stopped straight away.’

Beth pulled the Subaru off the road, and Jane rang Triple-0. Her voice quavered as she described the scene. ‘There’s a white car here in the ditch and about 40 to 50 metres further down the road on the right-hand side there’s a blue Mercedes, and behind that there’s a black car. They are both in the culvert on the right-hand side of the road pointing towards the bank. And the black car has a trailer with another car on the back of it.’

The emergency operator asked where they were, so Jane got out and ran back along the road a little way, looking for a sign or a reference point. She then returned to the car, took the first-aid kit out of the boot, and ran across the road to see if she could help the driver of the white car.

‘More cars were stopping,’ she said. ‘By the time I made my phone call, there were cars and people — people were stopping on the side of the road and getting out of cars — directly behind me, a four-wheel drive arrived, and then behind that was another little sort of slightly off-white sedan, after that I’m not sure. People started going to the wrecked cars. When we first arrived, everything was still and silent and nobody had actually got out of any vehicles, but by the time I had made the phone calls, I was aware of a woman sitting on the road, and a young couple had got out of the black car as well and were cuddling one another on the road.’

She estimated it was about 15 minutes before the first police officer, Sergeant Rob King, arrived from Oatlands. He’d received the call from Emergency and left after notifying the Hobart collision investigation team. He’d also summoned the SES, who received the call about 6.20 p.m.

Jane told Sergeant King she was the person who’d made the Triple-0 call, being first on the scene, and he asked her to wait around until he could take a statement.

By the time Sergeant King arrived, civilians were already comforting the crash victims and managing the passing traffic, directing cars around the debris on the road. Someone had been stationed on the far side of the curve to wave at cars and slow them down before they rounded the bend. At first, it seemed that only one occupant was trapped in a vehicle, the driver of the Mercedes.

Sergeant King went to ask how he was. He said, ‘I said, “Are you all right?” And he said that his leg was damaged. He couldn’t get out, as his leg was crushed in the car. I said, “Stay there, I’ll be there with you shortly.”’ At that stage, Rob didn’t realise the driver was Tim Ellis.

Rob moved to the Holden to check on Richard and Sarah, and then walked about 40 metres up the road to look inside the white Toyota. When he saw Natalia’s body, it was obvious nothing could be done to help her.

Others had looked in before him, including a nurse who’d stopped at the scene. She was checking on Richard and Sarah when Sarah asked her, ‘Why isn’t anyone going to that white car?’ The nurse told Sarah, ‘Don’t go there. There’s no point.’

Sarah and Richard looked at each other. They both had the same thought — that could have been them.

Caroline Badcock and her twin brother were driving north from Hobart when they came upon the scene. At first, they only noticed the two larger cars and the trailer. They pulled in just ahead of a prime mover from Australia Post, which had been travelling in the slow lane as it ascended the incline. Everyone jumped out, and Caroline ran to the two women beside the white Subaru. She asked, ‘Have you called the ambulance and everything?’ They said they had. Caroline heard them asking each other, ‘What was he doing? What was he doing?’

She ran across to the white car in the ditch and yelled, ‘Can anyone hear me in there?’ Getting no reply, she ran around the driver’s side and peered through the window. ‘I couldn’t see anyone where the driver would have been. And then I said to someone, “I think that the person in there is dead.” I then ran down to the blue car and saw a lady getting out of the back seat.’

This was Anita Smith, Ellis’s wife. When Caroline asked if she was OK, Anita replied, ‘I think I’ve broken my collarbone.’ Caroline helped her to sit on the side of the road, then went back up to the white car where she kept yelling out to ask if anyone could hear her. A doctor turned up before most of the police and ‘he just made the scene a bit calmer. He checked the body in the little car. He didn’t detect a pulse or anything,’ she said.

Caroline went back down to the Mercedes, where she and her brother stayed with Anita until the ambulances arrived.

They asked Anita about the man in the car and were told he was her husband, Tim Ellis. When they found out that his legs were stuck, they decided to look for something to open the door with.

Caroline said, ‘So then I turned around and ran back up to my car, thinking I might have something from the Pajero that we could use. I also grabbed a bottle of water for Anita. I then ran further along to an Australia Post truck to see if he had anything. We also decided to grab a blanket.’

Caroline was feeling very stressed at this point because they couldn’t find anything to open the door. ‘It was too hard. You couldn’t get into the car at all. And before I had run to the truck, there was a smell. I asked the others if they could smell something, and they went and detached the battery. They unhooked it.’

After that, a lot of things started happening. ‘Someone moved a blue vehicle into the sightline of the Mercedes so we couldn’t see the white car. Not sure who did that, but it was — I think it was pretty good of them.’ Caroline told me later that from where Tim Ellis was sitting, it was impossible to avoid the sight of the mangled Toyota.

Caroline then went to the people in the Commodore. ‘The man said he was doing OK and I told him to give his partner some water and keep her calm.’

More police were arriving, and Sergeant King delegated them to assist with traffic management and wait for the collision investigators to arrive. Nothing could be moved until they’d examined the scene. He collected details of people who’d arrived before he had and generally oversaw the management of the scene.

Once he had things under control, he returned to the Mercedes to reassure the driver that help was on the way. Rob got a shock when he realised he was speaking to Tim Ellis, whom he knew both as the DPP and from his former role as a Launceston lawyer.

Rob King later told the court, ‘I basically said, “Oh, it’s Mr Ellis!” and he said, “It’s Rob King isn’t it?” and I said, “Yes. Are you OK?”’ Rob outlined the next steps to get him free.

Rob went on, ‘In that same conversation I said to him “What happened?” And he replied words to the effect of, “I’m sure I was on the correct side of the road”, or it may have been, “I was sure I was in the correct lane”, something to that effect.’

Ellis appeared to be in extreme pain but didn’t show much outward emotion, Rob said. ‘He was controlling the pain as best he could. He wasn’t crying. He wasn’t devoid of emotion. He was a man in pain. That was the predominant feature.

‘I just said to him, “That’s fine, we’ll sort that out later. These guys will get you out and then we’ll get everything else attended to.” I then returned to the other matters at the scene.’

By now, the SES had arrived, and Rob asked them to cover the Toyota with a tarpaulin. He said, ‘It was in everybody’s line of sight — a grisly reminder that someone had died.’

Anita Smith was still sitting on the road being comforted by people who had stopped at the scene. Several people asked her what had happened and she said, ‘I don’t know. I was asleep.’ She was attended to by a doctor, Dr Michael Lees, who’d responded after the call was received at Oatlands. Paramedics weren’t a feature in rural Tasmania at that time.

Dr Lees recalled hearing Anita tell him and others she was asleep and saw nothing. He later told me that his first priority was Natalia, so once he’d checked that no one else was in urgent need of care, he walked up the road to the white car. A nurse was the only person nearby.

‘Natalia was still in her seat, but pushed well back,’ he said. ‘It seemed she had hit her head on the steering wheel as her car stopped suddenly from around 90 kilometres an hour.’

When a car stops abruptly at speed, even if the driver is wearing a seatbelt, the upper body can continue at the same speed until it hits something solid. In Natalia’s case, this appeared to be the steering wheel. Other injuries may have been caused by the engine block, which had forced its way into the car and pushed the dashboard onto her lap. Dr Lees could do nothing for her. He confirmed she had died at the scene.

Max Grey, the volunteer in charge of the SES team, said, ‘I didn’t recognise the Mercedes driver at first. He was still in the car. I basically assessed that the doctor was looking after him. I said to him, as I do with every person in cars, “Where is your mobile phone?”’ Ellis said it was in his pocket, and his wife’s handbag was in the car as well, so Max collected them both. He makes a point of collecting bags and phones, because they often go missing at accident sites.

Max told me Ellis was almost silent through the ordeal, as was Anita, who was sitting about two metres from her husband, on the roadside.

Max explained, ‘We removed the right-hand front door with the spreaders and cutters, which is quite difficult. The new cars are hard to get apart because of all the strengthening in the arches and the pillars.’

When they finally got Tim Ellis out, he was immediately transferred to a waiting ambulance and rushed to the Royal Hobart Hospital along with Anita.

Richard and Sarah Bowerman were assessed as being fit to continue their trip, which was going to be problematic as their transport was wrecked, but they said they knew people who lived nearby. After providing statements, they were allowed to go.

The collision investigation team of Constable Kelly Cordwell and Sergeant Rod Carrick arrived to measure, photograph, and assess the scene. Max lent Kelly Cordwell a hand as she moved around the Mercedes taking photos. He lifted the airbag so that she could photograph the dashboard, where he said he saw the speedo stopped on 110. Max told me, ‘He may have been speeding, or accelerating to try to avoid an impact. In any case that was an 80 zone at the time, as they’d just put new gravel on that stretch of highway. The signs came down a few days later.’

The next important person to appear was Ray Charlton, who drove the Coroner’s transport vehicle. He already knew that Tim Ellis had been involved in the crash, as his vehicle was tuned to the police scanner. He heard constant exhortations on the radio to get Ellis to Hobart before the three-hour statutory period for alcohol and drug blood tests expired. This brought a small smile to his lips. There had been similar smirks on the faces of various police throughout the evening, as they heard the news that Ellis had been in a road crash. The common question was, ‘I wonder what he’ll blow?’

Initially, this was just another call-out to Ray, who’d attended about 6000 deaths in his time transporting bodies to the mortuary. He rolled up in his van and got permission from Kelly to take Natalia from her vehicle.

He told me four years later, with a quaver in his voice, that for some reason Natalia’s death hit him hard and stays with him.

‘I saw her there, a lovely young lady. All the damage I could see was she looked like she’d hit her head on the steering wheel. Just sitting there, pushed back a bit, with her head to one side, resting on the pillar between the doors. I got in the opposite back door and lowered the seat back, then I reached down and cleared the debris from around her feet. In a lot of accidents, stuff hits the floor and stops you getting the person out easily. I said to her, “Come on, lovely, let’s get you out of here. You don’t want to be here any more, do you?”’

Going around to the driver’s door, he forced it open, and he and Kelly gently lifted Natalia out of her car and laid her on the stretcher.

Ray was thinking of the terrible waste as he got into his truck and headed back to the Royal Hobart Hospital’s Department of Emergency Medicine, where Tim Ellis and Anita were already being treated.

Tim Ellis had been blood-tested for drugs and alcohol at six minutes to nine p.m., just inside the statutory three-hour time frame. The results were zero for both, surprising (or even disappointing) many. He went upstairs to the operating theatre and ICU, and Anita was admitted overnight.

Natalia was going in a different direction. Ray’s first task was to arrange for a doctor to write an official death certificate. Although Dr Lees had declared Natalia’s life extinct, he had been acting in the capacity of paramedic at the scene, and a proper death certificate still had to be obtained. Then Ray and police members accompanied Natalia to the mortuary, where her name was added to the Death Book along with the hundreds of others who’d come before her. A blue luggage label was tied on her toe to identify her, and Ray tenderly undressed her, putting her clothes in a patient property bag. She was then transferred to a body bag and slid into a cold storage compartment until Dr Chris Laurence could conduct an autopsy.

Her driver’s licence had a Launceston address, so she was unlikely to be identified by next of kin that night.

‘You’ll have to come back and work your magic on her, Ray,’ one of the attendants told him. ‘She’s not going to stay that beautiful for long, once the bruises come out.’

Kris and Alan Pearn were watching something indifferent on TV that Sunday night in the lounge of their temporary accommodation. They’d sold their house, ready to move north in five days.

When she texted them that afternoon, Natalia had said she’d see them next day for lunch. She had Mondays off from her job at the Commonwealth Bank call centre and often spent that time with her parents.

Meanwhile, Kelly Cordwell had contacted the Launceston police and asked them to find Natalia’s next of kin. The police found her address on her driver’s licence and went to her apartment, where they gained entry and searched her computer for clues to her family. They found a lead to her sister and went to her house, then Natalia’s sister took the police to their parents’ home. At about 10.15 p.m., they knocked on the door. Kris opened it and was confronted with two uniformed officers and a tearful daughter.

Kris’s heart beat faster. ‘I don’t think I’m going to like what you are going to tell me,’ she said anxiously.

Her daughter pushed past and hugged her mother.

‘May we come in?’ the police asked. They explained, ‘There’s been an incident on the Midland Highway, Mr and Mrs Pearn. We’re very sorry to inform you that your daughter has passed away.’

Kris told me later, ‘I must have looked stunned. I was. I couldn’t believe I was hearing this. The police said the other driver was a 57-year-old man — he had a broken leg. They kept saying “Your daughter did nothing wrong”. Alan couldn’t speak. One of the police took my arm and sat me down. She said “We’ll stay until you get someone from your family here.” I rang my sister and just said “Natalia’s dead.” My sister said, “Oh shit! We’re on our way.”’

Kris’s sister and and her husband came straight over, and the police left after they arrived.

Everyone looked at each other. ‘What do we do now?’ ‘What does happen next?’ ‘How do we know it was Tali?’

One of Kris’s first thoughts on hearing of Tali’s death was that they’d have to break the news to her 80-year-old father. They all went to his house, where another sister answered the door.

‘Omigod! You look terrible,’ she said when she saw Kris.

Kris and the others explained about the ‘incident’ on the highway. ‘The police said she was in no way to blame,’ Kris told her father. ‘She was where she where was supposed to be. It was a 57-year-old man …’

Already bowed with age, Kris’s father crumpled. ‘You think he’d know better,’ he managed to say. ‘I can’t believe I’m going to bury one of my darling grandchildren.’

They all sat down for a while. Nobody knew what to do after news like this.

Someone told Kris she should try to get some sleep.

‘How can I?’ she shouted. ‘My Tali is gone!’ She thought she might never sleep again. ‘What are we going to do?’ someone said.

‘I want to go to K-Mart,’ Kris suddenly announced.

‘K-Mart?’ everyone exclaimed.

‘Yes, it’s open all night. I need lights and people. I can’t bear to think of darkness and silence.’ She and Alan stood up. Her sister said, ‘We’ll come with you.’

The little group arrived at K-Mart about 11 p.m. They must have looked a bit strange, because the guard on the door asked if everything was OK.

‘Our daughter has just been killed,’ Kris said matter-of-factly, still feeling strange at hearing those words come from her mouth. ‘We want to be somewhere where there are people and lights.’

When she told me this much later, I asked her what they did at K-Mart.

‘We walked around all night, until dawn. We hardly spoke, just moved from place to place and back again until the darkness had gone outside.’ They finally went home exhausted, realising the dawn heralded not only the end of that terrible night, but the beginning of a life without Tali.

‘If you bring a child into this world,’ Kris told me, ‘you stop being “I”, you start being “we”.’ From 24 March 2013, a part of the ‘we’ had been torn from her forever.

The aftermath of a death in a motor vehicle collision lurches from horror to humdrum routine, stunned disbelief to reluctant acceptance. On Monday, Kris’s sister and her daughter, Natalia’s cousin, took on the task of travelling to Hobart to identify Natalia’s body. Thanks to Ray, who had taken lots of care to prepare her, and because they went to Hobart so soon, they could hardly believe her injuries had been severe enough to kill her. They told Kris she looked as if she was sleeping peacefully.

The farewell party Tali had planned for her parents went ahead as a wake. Alan contacted the units in Queensland and said he and Kris needed more time before coming to take over. They needed to sort out what would happen to Tali. The unit managers told him he could take as long as he needed.

Kelly Cordwell and Rod Carrick began piecing together the information they’d gathered at the scene, with Kelly concentrating on photographs and witness statements and Rod on his estimates and measurements of the evidence left in the wake of the crash. The details for Caroline Badcock’s Pajero somehow got lost, but Kelly found her via postings on Facebook. (What did we do before social media?)

The general media got hold of the big news that Tasmania’s DPP had been driving a vehicle involved in a fatality. There was gossip that he must have been drunk, speeding, or both. The zero blood test results weren’t released to counter this gossip. Several police and former police took some satisfaction in the events swirling around Ellis, who was still in the Royal Hobart Hospital recovering. He had made enemies in some circles during his years as a vigorous defence lawyer.

Natalia’s friends vented their anger, sadness, disbelief, and sympathy for the family on social media. The mainstream media soon found Alan and Kris, and in those early days, Kris freely expressed the pain and anger she felt toward Tim Ellis for her daughter’s death. Her anguish spilled onto newspapers’ front pages and into lounge rooms, fuelling community anger that the second highest legal officer in the state could have been responsible for such a terrible situation. People wrote to the papers and spoke on talkback radio. Feelings ran high and it seemed the out-of-control spiral that had begun on the highway would continue indefinitely.

Word soon got out that Ellis been on the wrong side of the road. Calls were made for him to be removed from his high-paying job, and for him to go to jail like ‘normal’ people. Many of those he’d put in jail were delighted at his predicament. Speculation about what might happen to him stoked the media fire and Kris’s anger.

Tim Ellis’s left leg was pretty badly smashed up, and he’d be in hospital for some time. He was still in intensive care on the second day after the collision when he was visited by two colleagues: Mark Miller, the in-house principal legal adviser for Tasmania Police, with over 20 years’ experience in police prosecutions, and Jim Wilkinson, the president of the Tasmanian Legislative Council, member for Nelson and himself a senior lawyer of many years’ experience.

The beds and equipment are pretty close together in ICU, and curious hospital staff couldn’t help hearing some of the conversation, which centred on Tim Ellis having been ‘asleep’ before and at the time of the accident. The visitors and Ellis discussed the fact that sleep must have been the cause, even though Ellis had told Rob King at the scene that he ‘was sure he’d been in the correct lane’, or words to that effect. You can’t be sure of much if you are asleep.

Being asleep at the wheel raises interesting possibilities for a defence. These were exhaustively dealt with in a precedent-setting case, Jiminez v The Queen, in which the High Court considered the issue of a sleeping driver’s liability. The court pointed out that a driver who has fallen asleep behind the wheel isn’t acting consciously or voluntarily. So what approach should the law take? The High Court ruled that:

Where the question is whether a driver who falls asleep at the wheel is guilty of driving in a manner dangerous to the public, the relevant period of driving is that which immediately precedes his falling asleep. … The driving during that period must be, in a practical sense, the cause of the impact and death. The relevant period cannot be that during which the driver was asleep voluntarily. [My emphasis.]

Expressed in a simple sentence, this means that if you are feeling too sleepy to drive, but you consciously decide to keep going, then fall asleep and kill someone, you are guilty of dangerous (or negligent) driving, depending on the circumstances. You can’t be held responsible for something you do while you are unconscious — that is, asleep — but you can be held culpable if you consciously fail to take evasive action before you become unconscious. So is it an accident or not?

Tim Ellis was conversant with Jiminez and its ramifications, having not so long before contributed a position paper to a Law Reform Commission review on the subject. The Law Reform Commission recommendations are freely available on the internet in a paper entitled Criminal Liability of Drivers Who Fall Asleep Causing Motor Vehicle Crashes Resulting in Death or Other Serious Injury: Jiminez. The report was released three years before Tali’s death.

The key factor, in its most simplistic terms, is when sleep occurs. If the driver feels drowsy but deliberately keeps going, but later falls asleep and causes death or injury, that is negligent. If, however, the driver falls asleep without warning, it is beyond their control, and so is not negligent or culpable.

Two days after the terrible event, Kelly Cordwell came in to take the first statement from Tim Ellis. At that point, he was still banged up in hospital, in terrible pain, and not knowing if he’d lose his leg. His reputation was the subject of gossip and conjecture, and he was feeling remorseful about extinguishing the life of a popular, beautiful young woman.

He had also had plenty of time to reflect on Jiminez and anything else that crossed his mind. The visit from his two legal colleagues may have extended a life raft.

He told Kelly that he’d like to apologise to Kris and Alan Pearn. Kris had been pretty outspoken in various media grabs, and Kelly was probably worried that a letter would further inflame the situation.

When Kelly made them aware of Ellis’s wish to write to them, Kris and Alan didn’t know if they should agree or not. They didn’t have a lawyer for these purposes (most people don’t!) but a lawyer had helped them sell their home and business, so they asked him. He couldn’t see that any harm could come from it and thought it might even help a bit. So Kris rang Kelly back and stated her terms.

‘I want it in his own handwriting,’ she said. ‘No dictating to a secretary and getting it typed up. I want it from his heart, in his own words.’

Sure enough, a few days later a handwritten letter addressed to Mr Alan and Mrs Kristine Pearn and Ms Pearn (Natalia’s sister) arrived. It was a page and a half of fairly uneven, child-like printing written in pencil.

The letter acknowledged that the Pearns were ‘entitled to the fullest account of the circumstances of this terrible event.’ He told them, ‘The police tell me — and I fully accept — that my car was in Natalia’s lane and not the lane it ought to have been. I have no memory of how or why that came to be. I have no memory of a vehicle in front of mine, nor of two impacts with my car, only of one, and then stopping.’

He finished with, ‘All accounts of Natalia are of a vivacious and beautiful young woman who had achieved a great deal and would no doubt have continued to do so and to bring love and joy to her family. I am sure she was a wonderful daughter and sister and I am deeply sorry for your loss.’

When I read the letter a couple of years later, it seemed genuine enough. The Pearns thought so too when it arrived. ‘At least he’s manned up and apologised,’ Kris said to anyone who’d listen. ‘It doesn’t bring Tali back, but it seems he really is sorry and he’s accepting responsibility for what he’s done to our family.’

If things had ended there, you wouldn’t be reading this story.

Kelly Cordwell and her police colleagues had visited Ellis the just after Miller and Wilkinson. Ellis was on a morphine drip and fasting to prepare for another operation. When the police asked if he’d be happy to provide a statement, he said he was feeling OK to talk to them. He said he didn’t need legal advice (after all, he was a lawyer). He remarked later that a lawyer would have advised him not to give the interview so early. (Most lawyers would probably have advised him against giving one at all!). But he said, ‘I felt compelled to cooperate as much as I could and as early as I could.’

He must have forgotten about the earlier visit from lawyers Miller and Wilkinson and overlooked their advice, if they gave him any. There was a lot he couldn’t remember, including what had happened leading up to the collision.

Then he gave the police two alternatives, neither of which he’d mentioned in his letter. He said, ‘I might have got the lanes mixed up or I might have had a sleep problem.’

This wasn’t so much explaining as saying, ‘Look, I don’t know what happened. It could have been this or it could have been that’. He said he wanted to assist with the investigation, as ‘it was a mystery to me what happened’.

Police had noticed at the scene that neither his car or Natalia’s appeared to have braked, which probably indicated that the drivers didn’t see each other, or if they did, had no time to take evasive action before the impact. This seemed to add credibility to the possibility that Ellis was asleep, although the fact that his car was partly across the centre line and the impact was driver’s front end to driver’s front end seemed to suggest that Ellis may have suddenly realised and swerved at the last second. But he couldn’t suggest that because he said he was asleep.

Ellis later said in court that his recollections at the time of making his statement were true and very vivid. ‘But they were reflected,’ he said. He explained this by saying that he’d been told by police and media in the intervening two days between the crash and the police interview that there had been two collisions with other vehicles.

‘I had gained the impression somehow that they were both in the road, that is, they were in the piece of the road that I knew the accident had occurred. I didn’t know that the second one was of much less intensity than the first, nor did I know that it happened as I was going into the bank and the ditch, which were contemporaneous.’

Ellis vividly described his memory of the collision. ‘It comes to me in darkness, and this is a vivid memory that I still retain. Everything is darkness. There’s a whistling noise, very brief like you’d hear a missile landing on a TV show, just like that. Then there is an enormous noise, clearly metallic, and I don’t know whether I felt impact — well I felt impact but directionally I don’t know. And there’s tinkling and metallic noises and it’s as loud as anything — and this is all still in darkness. I felt an impact. I couldn’t see any vehicle because I couldn’t see anything. My first visual memory is of heading towards the bank. I am looking through a cracked windscreen but it has a reasonably clear view. I can see it coming. I’m not having any control of the vehicle and I’m bracing for an impact there. When it comes it doesn’t strike me as particularly hard. I didn’t register it as a metal-on-metal impact — if it was Mr Bowerman, and the accident reconstruction seems to say it was — and there was the ditch and the bank.’ He said he couldn’t remember two impacts.

He had a fairly clear picture of what he’d said to Sergeant King. He added, ‘When I was speaking to him, I thought it would be important to remember what I said to him, because it wasn’t unknown that I’d often had instructions that Sergeant King had recounted conversations with clients, not accurately in their view.’

Ellis added, ‘I may well have said, “I’m sure I was in the correct lane”, because I was sure. I can remember being loaded into the ambulance … and looking back down the road and seeing the accident debris there in the middle lane and thinking, “How did — how did that happen? I must have been clipped in my lane and swung in there.” So I was still of a belief I was in the correct lane.’

Kris decided she wanted to see Tali and say goodbye. Her family didn’t think this was a good idea, but she insisted. She and Alan travelled to Hobart, accompanied by some family members. Mortuary staff members were apprehensive too, because Natalia’s appearance had changed since the crash. Blunt trauma injuries can take a while to cause post-mortem bruises, and Natalia had collided with her steering wheel, had a possible broken neck and other trauma to her body caused by the impact.

Kris and Alan walked in to see their daughter for the last time. She was lying on a gurney, covered in a sheet. Only her face was visible. Instead of a wail of grief from Kris that everyone was expecting, they heard her talking urgently to Alan.

‘Omigod! It’s not her! It’s not our Tali. Oh God, some other poor mother is going to go through what I’ve been going through! It’s not our Tali, Al! Look at her!’

Alan was looking, sadly recognising the bruised and puffy face and closed eyes of Natalia as she’d been when he’d first saw her as a newborn baby, 27 years ago in the labour ward, looking just like the girl on the gurney.

‘It’s her, Kris,’ he said gently, trying to deal with his own grief and support his wife at the same time. ‘Say goodbye to our girl.’

Natalia’s memorial service was held in Launceston on 2 April 2013. About 500 people attended. Her friends had set up a novel way to remember her — ‘Nails for Tails’, Natalia’s nickname. The idea was for guests to have their nails done and donate something from the cost to either Road Trauma Support or the RSPCA in her memory. Her friends, both male and female, swamped the Nails for Tails Facebook page, enthusiastically posting each new do.

Kris and Alan were already committed to taking up their new arrangements in Surfers Paradise, and they eventually left at the urging of their families. They’d been looking forward to spending a new episode of their lives in a place where their family had often holidayed when the girls were little, and where they’d now have a permanent future home for their girls and their families. But life was really tough at times. Alan told me he could hardly walk in any direction without seeing Tali running ahead toward this or that hotel where they’d stayed, remembering fun in pools and on the beach and shopping in Cavill Mall, the main street of Surfers. Kris carried Sugar, Natalia’s chihuahua, like a baby everywhere she went, telling anyone she encountered that the dog belonged to her daughter, who was killed by Tasmania’s DPP. Kris wasn’t doing well.

Tim Ellis left hospital in April on crutches. He went home to wait for the results of the police investigation. It had been decided that he couldn’t return to work while being investigated for causing a death, so he filled the days with rehab, sleeping, reading and other quiet pastimes, suspended on full pay. Anita returned to work in the Justice Department, where she was the respected head of the Guardianship Board, so Ellis had a lot of time to think during his long days alone. His deputy, Daryl Coates SC, took over as acting DPP.

Kelly Cordwell remembers this time with great distaste. Whenever anyone realised she was investigating the circumstances of the crash, they’d give her a hard time. She was bombarded with questions and opinions about what should be done with Mr Ellis in shops, at parties, at family gatherings, at work, and, of course, when she encountered anyone from the media. Kelly is a tall, calm-looking young woman, highly respected by her colleagues, but during the months after the collision she sometimes wished she was a little, unobtrusive person who could crawl unnoticed under a rock.

Ellis was indirectly her superior officer in justice and corrections, though until she began her investigation they’d never met, so fortunately for her, the decision about what should happen next wasn’t hers to make. She told me later that once all the investigations and interviews were done, the case was sent interstate so that someone else could decide the charge against Ellis. The charge decided on was negligent driving causing death. Along with manslaughter, this is one of the few crimes where a ‘responsible citizen’ with no previous criminal record may be sent to jail if convicted.

The actual crime set out in s167A of the Tasmanian Road Traffic Act is causing death by driving a motor vehicle at a speed or in a manner that is dangerous to the public, having regard to all the circumstances of the case. The ‘public’ here may include a passenger. If the motor vehicle is being driven on a public street, the court takes into account the nature, condition and use of the street, and the amount of traffic at the time, or which might reasonably be expected to be, on the street.

This crime is a statutory alternative to manslaughter, and sentences are normally less. If the act of driving has been established as voluntary and intentional, it is for the court to decide whether the driving is objectively dangerous. If the act of driving is involuntary, the charge is less. The driver’s opinion on this point is irrelevant, even though in the past, Ellis had been the man who made the decisions on whether to lay similar charges against others.

Investigations take time, particularly when the issue is sensitive and the outcome political. The DPP is appointed by the government of the day, and the government had specified that a DPP would be appointed until he or she was 70, could only be dismissed by the State Governor, and even then only for incapacity, misbehaviour, or bankruptcy. Rules about a DPP being suspended had either not been anticipated or had been forgotten, so while the police were doing their job, Ellis sat home in limbo.

Part of the police investigation involved trying to replicate Ellis’s actions when he’d driven in the wrong lane around a sweeping bend for up to 1000 metres while he said he was unconscious. This was the distance police calculated based on his speed and the various sightings by witnesses.

Police closed the road between the point where Ellis was first reported by witnesses and the point of impact so that Kelly Cordwell could try to reproduce the conditions. She attempted several times to drive through the bend at various speeds without adjusting her steering — that is, as if the car was driving itself because she was asleep. The S-Class Mercedes used for these experiments wasn’t exactly the same model as Ellis’s, and for this reason and others there was controversy about the admissibility of the results at the trial. Ellis’s counsel would say, ‘It’s not simply a matter of jumping in a car that looks like a Mercedes, or drives like a Mercedes, or is a Mercedes but it’s not the same Mercedes, and then making up a course of events for the purpose of demonstrating something that didn’t happen. It can’t possibly help … and it’s not relevant because it’s not the same event. It’s a different event of driving and it’s done by different people in significantly different circumstances.’

Which was, of course, correct. Nevertheless, the experiments were filmed, and Rod Carrick travelled at Kelly’s side as an observer. Kelly estimated that she had to make five adjustments to her steering, and Carrick said he saw three. The numbers may have differed, but they still demonstrated that it was almost impossible to go around that bend without some conscious input from the driver.

The accident investigators also filmed what happened when they removed their hands from the steering wheel to see if it was possible to drive that 23 to 26 seconds effectively without being in control of the vehicle, potentially asleep or in some other non-conscious non-voluntary state. That didn’t work. If the car wasn’t actively steered, it simply veered off to the side of the road, back onto the correct side of the road, or even potentially off to the far lane and into the roadside.

In the early stages of the investigation, Kelly discovered that a mobile phone was being used in the Mercedes, apparently sending a text message, only 30 seconds before the impact. Kelly reviewed the statement Anita had given Rod Carrick at the scene. She’d told Carrick that to the best of her recollection, somewhere south of Campbell Town, she received and responded to a text from a friend they were planning to see at Easter in Byron Bay. Anita told Carrick that her friend had said in the text that there was a longer message in her inbox, so she opened that and typed a reply.

Checking further into the statement, it seemed that the CD stacker in the Mercedes held six CDs, which Tim could eject by pressing a button on the steering wheel for each one. Anita’s task was to put the ejected CDs into their cases and insert six new ones into the stacker on the dashboard in front of her, while juggling them on her lap.

Anita said that the whole process was interrupted by texting and messaging her friend, so it probably took place over some period of time. ‘Once the CDs had finished playing, Tim wanted to check the cricket scores and he was listening to the cricket, so we probably weren’t talking,’ she said. She thought the text and email came shortly after 6 p.m., either while she was sorting the CDs or when the cricket was on. She’d discussed the plans for Easter with Tim as she sent the reply.

I remember thinking later that between ejecting CDs, tuning in to the cricket, and talking with Anita about the Easter arrangements — all things you might do to stay awake if you were feeling sleepy — Ellis can’t have been asleep for very long before the impact.

Ellis was eventually summoned to appear on 1 October 2014 to enter a plea on the charge of negligent driving causing death.

By then, the Pearns had moved to Queensland, but Alan decided to fly down to attend the hearing. He expected it to be over in ten minutes, as Ellis had already told them in his letter that he knew he’d killed Natalia and that he knew he’d been in the wrong lane. Kris didn’t feel up to facing him, but she said she’d hover near the phone until Alan called with the news.

Taking his seat in the crowded courtroom, Alan was surprised to see someone he recognised in the seat directly behind him. It was former police commissioner Jack Johnston, whose face had been plastered across the media for more than a year in 2007 and 2008, when he was engaged in a very public stoush with Tim Ellis. Johnston, 40 years a cop and six months chief of Tasmania Police, had been charged with two counts of disclosing official secrets. He’d been strip searched, fingerprinted, and thrown into a cell without his shoes, ‘like any drunk on a Saturday night’, Johnston told me later. He regarded it as an unnecessary humiliation.

Eventually, the allegation against Johnston was thrown out by the Supreme Court. Ellis sought special leave for an appeal to the High Court, but it was dismissed. Nevertheless, other ‘code of conduct’ charges, mostly made by Ellis and a senior policeman, still hung over Johnston and prevented him from returning to work.

‘People seem to forget that I am still the commissioner,’ he told the media at the time. ‘It’s an interesting experience, taking off your leather shoes and putting them outside the door in a cell row where all the others are old Reeboks and Nikes with holes in them. I have done nothing wrong. There is a thing called justice that needs to be considered.’ (Good luck with that, I’d thought at the time.)

Johnston said it had given him a new perspective on his job ‘when you live your life in the belief that your home is potentially the subject of listening devices, your telephone records are being checked on a regular basis and potentially there’s a telephone intercept in place’.

Several years later, Johnston recounted his still simmering despair and anger to me. Listening to his indignant account, I had to hide a small smile. How many times have I heard an accused person say the same thing about the police?

He said, ‘I don’t think there are enough avenues available to people who are innocent to become aware of what is being done to them. I think some of the things that are happening are not subject to sufficient oversight, and that should change.’ Amen to that!

When he was charged, Johnston believed the prosecution reflected his ‘frosty’ relationship with Ellis over the years, including a spat over the independence of the police. Ellis refused to respond to the assertion, but his deputy, Daryl Coates SC, dismissed the claim. Coates pointed out that he, not Ellis, had brought the indictment and criminal complaint. After that, Johnston’s lawyers were quick to reassure the court that there was no assertion of improper motive.

And here he was now, retired citizen Jack Johnston, sitting in another court on an unrelated case. Uncharitable folk might have assumed that he was there to see how Tim Ellis handled ‘getting his’, although he assured me later that wasn’t the case. He was just curious, he said.

Alan’s heart beat fast when he saw Ellis sitting with his defence team at the bar table. Why did he need all those lawyers if he was guilty?

Alan soon found out when Ellis was called into the dock. He hobbled across the court and climbed the couple of steps with apparent difficulty. The charge was read out to him, ‘Negligent driving causing death’. Looking straight ahead, his face still red with the exertion of climbing into the dock, Ellis responded, ‘Not guilty’.

‘I felt like I’d been kicked in the stomach,’ Alan told me later. ‘Absolutely gutted. How could he plead “not guilty” when he had confessed to us, in writing, that he’d killed my daughter and acknowledged he was in the wrong? Wasn’t he man enough to face the music in court, take his punishment and let us try to get on with rebuilding our lives without Tali?’

Many members of the public I speak to in the course of my research have no real understanding of the justice system. (Quite a few legal practitioners don’t seem to either!) These lay people aren’t stupid; it’s just that they rarely encounter lawyers, courts and legal intricacies. Those who do get swept up in the ‘justice game’, as Geoffrey Robertson QC calls the legal process, aren’t prepared to hear a person plead ‘not guilty’ when they appear to have done what they are accused of. Sometimes they get lost in their grief and forget that everyone has the right to a fair trial and the presumption of innocence. It was Ellis’s right to plead ‘not guilty’, but it meant that the Pearns would be subjected to the drawn-out agony of a trial.

Alan flew home with the bad news. Kris was inconsolable. She could barely get out of bed each day, anticipating the prospect ahead. The media reports, the ducking and weaving, the whole dreadful scenario being played out in the public arena. She decided that Ellis’s apology to her family was ‘worthless and nothing but self-serving rubbish’, so she sent a copy to the prosecution.

Once it was established that Ellis wasn’t going down without a fight, a timetable had to be set for a trial in the Magistrates Court, the correct jurisdiction at the time for a charge of this nature. But on a tiny island where all the lawyers went to school together, who would hear such a charge against an incumbent DPP? There was talk of moving the whole trial to the ‘mainland’, as Tasmanians call the rest of Australia.

Chief Magistrate Mike Hill said he had a conflict and then canvassed every magistrate in Tasmania. Nobody grabbed the poison chalice. Some were friends of Ellis, some felt their decision wouldn’t be popular, others had private views or memories of Tim Ellis’s belligerence and were reluctant to become involved.

Then Magistrate Chris Webster, Jim Wilkinson’s former legal partner in the firm of Wallace, Wilkinson and Webster, stepped up to the plate. He agreed to hear the evidence against the suspended DPP, because someone had to do it, and having practised law at the opposite end of the island and never having really encountered Ellis in court, he couldn’t think of any reason why he couldn’t. In addition, Webster’s private practice before his magisterial appointment had mainly consisted of going into bat for accident victims — workplace, traffic and so on. He had an understanding of how a moment’s inattention could cause a collision, but he hadn’t previously encountered the proposition that twenty-six seconds of inattention, driving while asleep, could form a defence. He probably thought he might find the trial interesting.

To overcome the perceived possible influence of the Tasmanian legal old boys’ club, an interstate barrister was brought in from the NSW DPP’s office in Sydney to prosecute on behalf of the Tasmania Police. John Pickering QC had completed law in 1993 and spent most of his career at the DPP’s office, where he worked as a solicitor and later as a barrister. At the time of Ellis’s trial, he’d been appointed NSW Deputy Director of Public Prosecutions and taken silk. His skill was legendary from the law courts to the basketball courts, and he also played golf, cricket, and soccer. ‘It’s all good, as long as it has a ball in it’ is the motto for many sportsmen who enjoy ball games.

Ellis assembled a top local team of his contemporaries, briefed by E. R. Henry Wherrett & Benjamin (HWB), an establishment firm of solicitors in Hobart. David Rees, a principal of that firm, briefed Garth Stevens from HWB (who had previously worked at the ODPP) and Michael O’Farrell, who had worked at the Crown Solicitor’s office and Solicitor General’s office before taking silk. The old boys’ network sprang into action, and ‘all the cracks were gathered to the fray’.

The trial commenced on 24 March 2014, exactly a year to the day after Natalia’s death. Was that a cruel accident, or a twist in the justice game?

Neither Kris nor Alan felt capable of attending, although friends and relatives did. Media interest was huge.

One of the rules in the justice game involves a session called a ‘voir dire’, literally ‘to see and tell’, originating from an oath taken by jurors to tell the truth (Latin: verum dicere). These days, the process generally involves argument about the admissibility of material that one side or the other wants to present as evidence but the other side doesn’t. If a jury is sitting, it is sent out of the court so they don’t hear discussion they may not be able to disregard later if the material is ruled out. A judge can also seek a voir dire in order to reprimand counsel out of the jury’s hearing, or for counsel to make submissions as to the running of the court.

If a lone judge or magistrate is sitting, he changes wigs and arbitrates on the arguments until one side (or neither side) is successful, at which time the court reverts back to trial mode.

Ellis’s trial kicked off with opening submissions, during which Pickering said, ‘The prosecution will contend … that it would be impossible to remain on that road for that period of 800 to 1000 metres if you were not in a position to consciously and voluntarily drive a car. Anyone who had fallen asleep while driving the car simply would have left the road. Once the prosecution establishes conscious and voluntary driving, the prosecution will submit there is no other reasonable hypothesis consistent with innocence on the defence of negligent driving occasioning death … The Crown’s case will be that we will exclude any other reasonable hypothesis as to why he crossed onto the incorrect side of the road and why he maintained that position on the incorrect side of the road for 800 to 1000 metres. Your Honour, in a nutshell, that is the Crown case.’

O’Farrell countered that the prosecution had alleged negligence, ‘but this must be contemporaneous with the tragic event, otherwise there will be no causative link’. The ‘hypothesis which cannot be excluded on the facts of this case’, he said, was that the position of Ellis’s vehicle was ‘consistent with him having significantly impaired perception and loss of consciousness immediately before impact’.

This hypothesis was supported by Ellis’s memory of the accident: as he told police at the time, he didn’t remember the lead-up to the collision with Natalia’s car or the collision itself; his ‘first memory [was] when he struck the second vehicle, being the Commodore. Immediately after the impact he became conscious and was able to relate the events accurately to the police after the accident. So Your Honour, we submit that at the end of the day the prosecutor’s hope to exclude all reasonable hypotheses will not succeed.’

So that was the case. Was he drowsy and therefore negligently didn’t pull over when he began gradually falling asleep; did he suddenly drop off to sleep with no warning; or did he drive his car unconsciously but immaculately for up to 1000 metres over a period of about twenty-six seconds? As Alan Pearn said to me much later, ‘The whole case was about two words — drowsy or asleep.’ The lawyers seemed to take a long time to reach the same conclusion

Anita Smith was called first, as a witness for the prosecution. She wasn’t obliged to appear in that capacity; the Evidence Act allows spouses to refuse to provide evidence in a criminal prosecution against their partners, but she chose to do so. In many ways, her evidence wasn’t all that helpful to her husband, and she produced a couple of baffling replies to Pickering’s questions.

They first went through the events of the day, bed about 10 p.m. the night before, good sleep, early start. She said that Ellis suffered from sleep apnoea, but had worn his mask to bed and apparently slept well.

The mask was a Continuous Positive Airways Pressure (CPAP) device, which she described as consisting of ‘a small plastic box from which a hose extends. There is a mask at the end of the hose with elastic straps that go around your head to seal the mask. When it’s activated, it blows quite strong air pressure into the mouth and nose.’ She said he’d been using it for about 18 months, had got quite used to it and found it helpful.

‘It took some adjusting to. It interrupts your sleep. But eventually he adjusted to it and became a consistent user.’

Pickering asked, ‘Before he obtained the machine and started using it, did you ever notice Mr Ellis being tired or just dropping off at various times to sleep, watching TV or at work?’

She said she rarely saw her husband at work, but he dropped off in front of the TV at times.

‘Before he was diagnosed with sleep apnoea and obtained the machine had you ever noticed his being tired whilst driving at all?’ asked Pickering.

‘Only to the same extent as another person, that we’d sometimes share the driving, but if we’re together he’s most often the driver, but often I might offer to take over.’

‘Had you ever seen him look as though he was falling asleep at the wheel whilst driving?’

She said during their 14 years together, ‘I would think over that period of time I would have observed that at one time or another’ and she said that at any of those times she’d start a conversation, or offer to take the wheel, but he usually preferred to drive, especially if they were travelling in his car.

Pickering asked, ‘Did you have any concerns that there was any danger driving with Mr Ellis because he suffered from sleep apnoea?’

‘I can’t remember it ever having crossed my mind. I think Tim is a very safe driver and I always feel safe being his passenger. Prior to the accident, my main association with sleep apnoea was snoring and the affect it had on our sleep. I wouldn’t have associated it with the act of driving prior to this accident.’

This was the first of Anita’s strange admissions. Surely she knew that her husband was going to rely on the fact that he suffered a sleep disorder that caused him to fall asleep at the wheel, but she said she had no fear of travelling as his passenger and no knowledge that sleep apnoea might cause a driver to fall asleep suddenly.

The second strange thing, following on from this, was that ‘he always drove’. If Ellis knew (or believed) that his sleep disorder might cause him to suddenly fall asleep at the wheel of a car, surely that could be construed prima facie as negligent?

It later turned out that he had a letter from his doctor saying that he’d be as safe to drive as anyone else if he continued with the CPAP treatment. But this letter didn’t support his claim that the sleep apnoea had caused him to fall asleep.

Pickering didn’t pick up on these points just then, but moved back to the events leading up to the crash.

Anita said that on the trip north, they drove to Campbell Town, picked up some food to take to Tim’s parents for lunch, had lunch at Longford (‘No alcohol was on offer there’) then went on to Legana for afternoon tea with her parents and a dog drop-off stop at her sister’s before heading back to Hobart about 4.15 p.m. Just a nice day out in the country.

As they were in Tim’s car, she presumed he’d be the driver.

On the way back, ‘We were quite relaxed. It had been a really pleasant day. We had discussions about how much Tim’s mother, who had been sick since Christmas, had improved. We talked about my father’s impending trip to New Zealand. We just chatted generally. Just outside of Campbell Town, Tim said he was sick of driving but he was happy to carry on.’

Pickering asked for clarification. ‘When he said he was sick of driving, did you form any impression about what he meant by that? Whether he was talking about being fatigued or tired or just sick of it?’

‘Just sick of it. Those are the words he used. I just made a feminist joke about the fact because he’s a man he drives.’

She couldn’t remember if she was looking at him or had felt any concern that he might be too tired to drive. She then received the text message from her friend about Easter and as well as responding to that, she assisted Ellis by catching and putting away the used CDs as he pressed the ‘Eject’ button on the steering wheel. She thought these activities probably took place over some period of driving time.

She recalled that ‘once the CDs ran out he wanted to check the cricket scores and he was listening to the cricket, so we probably weren’t talking, but I think I probably let him know that Therese was asking about our arrangements or something like that’ during the receiving and sending of the messages. She continued, ‘I had my head down for quite a significant period of time typing and sending that text and that message and I was very much in my own little world — just focused on that task. I remember just a very brief glimpse as we were north of Tedworth — just looking out noticing the farm at Tedworth and thinking right, we’re there — just consciously registering where we were in terms of the journey, but my field of vision was restricted to the things in my lap. I didn’t look up in those last 20 or 30 seconds.’

Here was another curious bit of information. A witness who stopped at the scene to comfort Anita, and Dr Mike Lees, who attended from Oatlands, both later told me they thought they heard her say she saw nothing because she was asleep. (Maybe she said ‘He was asleep’ — there’s a lot of confusion after crashes.) Dr Lees wasn’t called as a witness, even though he attended Natalia and the injured at the scene.