Chapter Three: Swimming Lessons for Pete

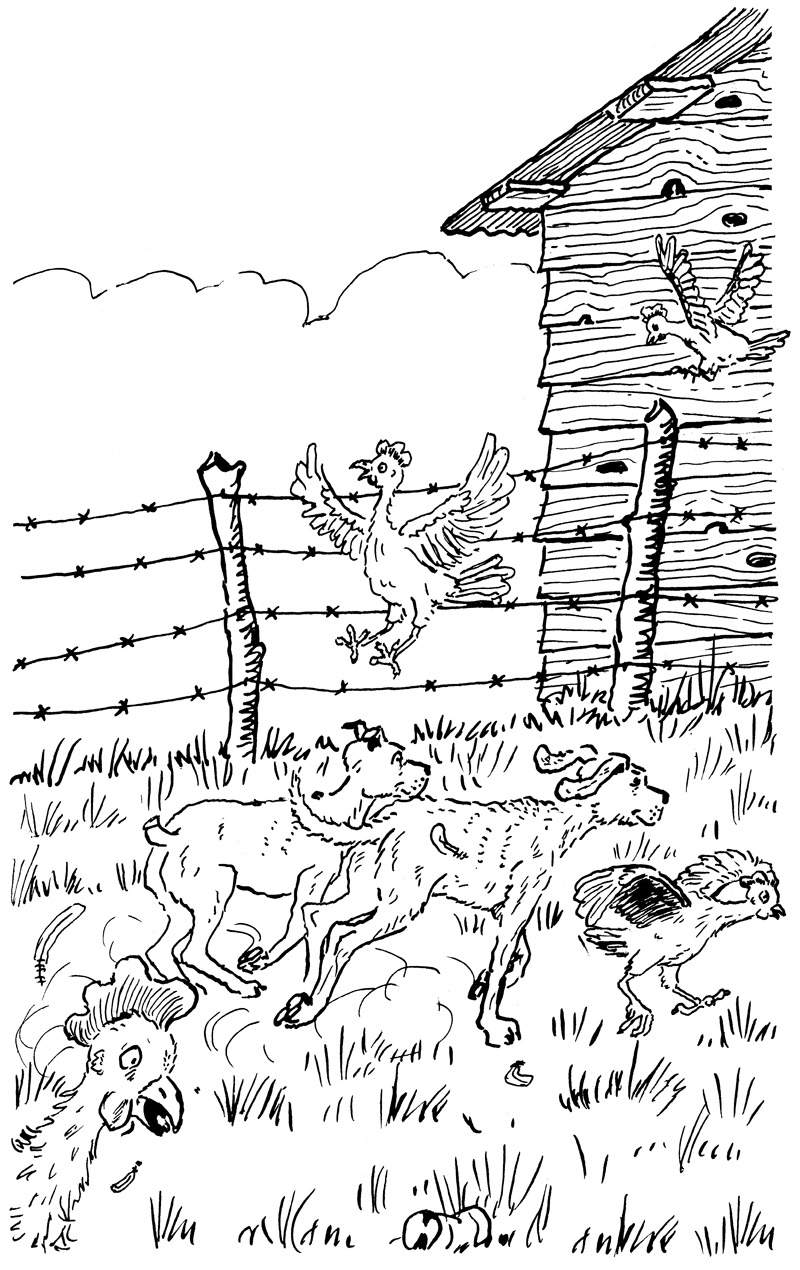

We went sprinting up the hill, trotted past the chicken house, scattered the chickens, and went to the machine shed.

I’ve always enjoyed scattering chickens. Even on days when I’m in a bad mood and nothing seems to be going right, I can run through a bunch of chickens and, I don’t know, it just seems to give new meaning to my life.

I was still feeling sore from my beating the previous night, and also hungry, so I spent several minutes crunching Co-op dog food from the overturned Ford hubcap which serves as our bowl.

Many times I’ve wondered how much it would cost the ranch to buy us a real bowl, instead of a nasty hubcap that retains the taste of axle grease. Yes, I know. Grass is short and cattle prices are down, but I also know that the cowboys on this outfit eat out of plates and bowls, not hubcaps.

It’s funny to me that there always seems to be enough grass and enough cattle market to buy plates for them, but you mention buying anything decent for the Head of Ranch Security, and suddenly we’re in the midst of a drought and a plague and a depression!

I mean, the cattle market has fallen off the edge of the world and there ain’t a sprig of grass left in the pastures and everybody’s going around in rags and their toes are poking out of the holes in their boots and they’re having to boil tree bark to feed the children.

It makes a guy think that the people in charge don’t realize just how important their dogs are to the overall . . . oh well.

I ate dog food out of the hubcap and tried not to think of all the injustices in the world. Too much brooding can ruin your digestion, and life without digestion is . . . something. Unbearable. Full of burps. Hard to bear.

Yes, we crunched our dog food: hard, dry, yellowish kernels that come in a fifty pound sack. Sometimes I wonder what kind of stuff they put into those kernels, and other times I’d just as soon not know.

I noticed that Drover was making a lot of noise. “Do you suppose you could be a little quieter in chewing your food?”

“Well, I don’t know, Hank. It’s pretty hard.”

“Of course it is. It’s always harder to eat with manners than to eat with the wild abandon of a hog, but who wants to sound like a hog?”

“Not me.”

“Hogs make no pretense at being civilized, Drover. They crunch and smack and grunt, and nobody cares because they’re only hogs who eat like pigs.”

“That makes sense.”

“But we’re not hogs, Drover. We aspire to something higher and better. We try to bring a certain air of dignity to the ritual of eating. The act of imposing dignity on the chaos of experience is called civilization, and protecting civilization has always been hard.”

“Yeah, but I meant the kernels were hard.”

“Oh.”

“Hard to chew.” He crunched a kernel.

“Yes, I see what you . . .” I crunched a kernel, “mean. They are hard, aren’t they? In fact, they hurt my teeth.”

“Yeah, and they hurt my gums.”

“You shouldn’t be chewing gum while you eat, Drover. Not only do you run the risk of swallowing it and gumming up your entrails, but it’s also in very poor taste.”

“Yeah, it tastes kind of like sawdust to me.”

“Exactly. But taste and manners are like grease in the ball bearings of experience. Without the grease, we would have nothing but friction and disharmony.”

“You reckon they add a little grease to improve the taste?”

“There’s no explaining taste, Drover. Some dogs have it and some don’t. Those of us who do, and I include myself in that group, have the added burden of defending it against the endless assaults of the mindless rubble.”

“Yeah, and the chickens.”

At that very moment, a chicken came up to our dog bowl and appeared to be thinking of pecking into our food. I lowered my head, lifted my lips, exposed my teeth, and snarled.

“Get away from our food, you feather merchant!”

She squawked and ran, and we went back to our eating. Drover wore a big grin on his face as he smacked and crunched.

“Boy, we’re pretty good at defending our taste, even if it tastes like sawdust.”

“Someone has to do it, Drover, and it might as well be us.”

All at once we heard a commotion coming from somewhere down below. My ears, which are very sensitive and operate pretty muchly independent of the rest of my body, picked up the sound, and within seconds had passed the information along to Data Control.

There the sound was analyzed, broken down into vectors and parameters, and given a specific location. The mental printout which appeared behind my eyes contained this brief message:

“DISTRESSED CAT NEAR SEPTIC TANK.”

I went on eating. We respond to most distress calls at once, but a cat in distress can always wait until we finish our meal.

But then I heard the back door slam. I paused, switched my ears from automatic to manual, lifted them a half-inch, and opened the exterior flaps to increase their sound gathering capacity.

Footsteps on the sidewalk. The squeak of the yard gate. The snap of the gate latch. Footsteps on gravel. Sally May’s voice.

“Alfred? Alfred? Where did you go?”

More footsteps on the gravel, moving down the hill towards the gas tanks. “REEEEEEEER!” That was the cat again, no problem there. Ah ha! A splashing sound. A child laughing. Then Sally May again.

“Alfred! What on earth?”

I sighed and stood up. “Swallow your food, Drover, we’ve got a Code Three down at the septic tank.”

Drover had a mouthful. “Acktock cwqbhd sclcke bdkdkejald.”

“I can’t understand you. Your mouth is full.”

“Cvkwlcled ckwoeidke bjeildhck flwe.”

“Swallow, clear your moth . . . your mouth, that is, and try it again.”

He chewed and swallowed hard. “I said, my mouth is full.”

“No, it’s clear now. I’m getting a good copy on you.”

“I know, I just swallered what it was full of.”

“I know you just swallered it. That’s what I told you to do, that’s what you did, so what’s the problem?”

“I don’t know. My mouth was full and I couldn’t talk and that’s what I was trying to tell you.”

“You tried to tell me but your mouth was full and you weren’t able to communicate your message, is that correct?”

“Yeah, that’s exactly what happened.”

“So . . . what is the point of this discussion?”

“I don’t know. Don’t run around when your mouth’s full or you might choke . . . I guess.”

I glared at the runt. “You’re taking the time to tell me that when we’ve got a Code Three down at the septic tank?”

“I was just minding my own business and trying to eat and . . .”

“Drover, sometimes I think . . . never mind. We’ve got a job to do. Stay behind me and let’s move out!”

We went streaking away from the machine shed, down the hill, past the gas tanks, and towards the overflow of the septic tank. There the scene unfolded before us.

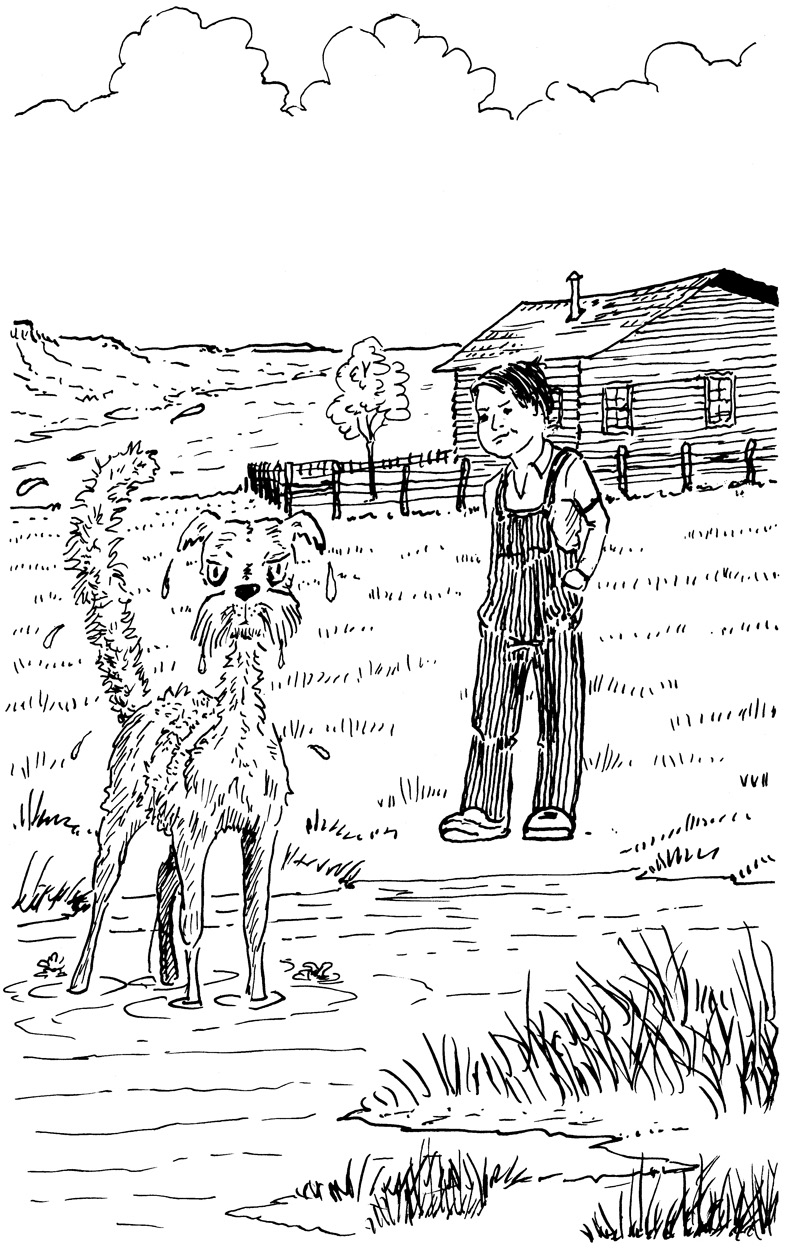

Little Alfred had just pitched the cat into the overflow of the septic tank. The cat appeared to be waterlogged and angry. His ears were flattened against his head and water dripped off his chin. He bounded through the shallow water until he reached dry land, where he stood dripping water and glaring daggers at anyone who cared to look at his sorry condition.

Little Alfred was laughing, but when he saw his mother pick up an elm switch his smile suddenly vanished. Sally May snatched him up, turned him over her knee, and dusted the seat of his britches.

She turned him loose and stood over him. “You’re just being terrible today! I don’t know what’s gotten into you, but I won’t allow a child of mine to be cruel to dumb animals.”

(She was referring to Pete there.)

“First you pulled Hank’s tail and then you threw poor Pete into the water. That’s not nice, young man, and you ought to be ashamed of yourself!”

“Well,” Alfred sniffled, “he needed a baff.”

“Cats don’t bathe in water, Alfred, they wash themselves with their tongues.”

“Well . . . his tongue was dirty.”

“No, his tongue was not dirty. You were just being mean and cruel, and I’ve got a new baby in the house and I can’t be watching you every minute of the day. If you don’t play nice, you’ll have to come inside and take a nap.”

She started back towards the house. When she passed me, she stopped and scowled. Maybe she noticed that I was, uh, smiling. I mean, tossing Pete into the septic tank ain’t exactly my idea of a serious crime. Furthermore, it had been his cousin, Sinister, who had pulverized me the night before.

She shook her finger in my face. “And don’t you be giving my child any more ideas about tormenting the cat, Hank McNasty.”

HUH? Who, me? Well, hey, I . . .

“I know what you’re thinking, and you’d better leave my cat alone. If I hear more yowling, I’ll . . . I don’t know what I’ll do, but you’ll be the first to find out.”

Yes ma’am.

She stormed back to the house. If she’d known what Little Alfred had on his mind, she wouldn’t have left so soon.