The coldest war: toward a return to Great Power competition in the Arctic?

by Stephanie Pezard

STEPHANIE PEZARD is a senior political scientist at the RAND Corporation. Her research focuses on European security and transatlantic relations; Arctic security; strategic competition; deterrence and use of force; measures short of war; and security cooperation.

! Before you read, download the companion Glossary that includes definitions, a guide to acronyms and abbreviations used in the article, and other material. Go to www.fpa.org/great_decisions and select a topic in the Resources section. (Top right)

Ice floes surround the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Healy in the Arcitc Ocean on July 29 (BONNIE JO MOUNT/THE WASHINGTON POST/GETTY IMAGES)

The major changes that the Arctic is experiencing as a result of global warming are repositioning it as a region of strategic importance, and as such it attracts increasing interest from both Arctic and non-Arctic nations. The U.S., which has sometimes been described as a “reluctant” Arctic nation, is quickly shifting toward a much more active Arctic policy. This shift finds its origins in a view of the Arctic as an arena for great power competition, where Russia and China are advancing their interests and the U.S. runs the risk of falling behind if it does not react quickly. This chapter lays out the characteristics of the Arctic’s different sub-regions; recalls its role during the Cold War and in its aftermath; identifies key U.S. priorities in relation to the Arctic; examines how Russia and China’s policies in the Arctic might challenge these interests; and describes how the U.S. works with its allies to advance its interests in the region. It concludes with a discussion of how U.S. policy choices might constrain or, on the contrary, play an enabling role for U.S. ambitions in the Arctic.

The Arctic is commonly defined as the area located north of the Arctic Circle, which forms an imaginary line at latitude 66°33’ North and corresponds to the southernmost point where the sun is visible for 24 hours on the June Solstice. By that definition, Arctic nations include the U.S. (by way of Alaska), Canada, Denmark (by way of Greenland), Norway, Russia, Iceland, Sweden, and Finland, with the first five being also Arctic coastal states.

In spite of the use of the singular, the Arctic is a diverse region, with different areas showing unique landscapes, populations, and economic patterns. The “European” Arctic, which goes from Greenland to Russia via Norway, is more densely populated and exploited economically than the “North American” Arctic comprising northern Canada and Alaska. This is the result of various factors, from climate—the Gulf stream keeps northern Norway and the Russian port of Murmansk ice-free all year long—to national politics, with the Soviet Union taking a proactive role in the industrial development of its Arctic region. As a result, the largest Arctic cities are in Russia, with Murmansk counting about 300,000 inhabitants, while the largest city in the North American Arctic is Greenland’s capital city Nuuk, with a little above 17,000 inhabitants. Arctic populations also include numerous indigenous people. Alaska, for instance, counts 11 distinct native cultures. In some cases, these indigenous populations’ historical lands cross modern boundaries. The Sami people, for instance, live in Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia.

The Arctic is experiencing the effects of climate change at an accelerated pace, resulting in profound transformations to its physical environment as well as to the human activities that it can sustain. The 2019 “Arctic Report Card” published by the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) highlights dramatic changes to the extent and thickness of sea ice, the Greenland ice sheet, sea and land surface temperatures, and snow cover, which in turn have important consequences for the wildlife, fisheries, and the livelihoods of indigenous populations living in these regions. These changes have an impact beyond the Arctic: As it melts, the sea ice that reflects sun rays into the atmosphere is replaced by water, which instead absorbs solar energy, further contributing to global warming. A warmer climate has broad implications in the Arctic, from the opening of new sea routes for shipping to the displacement of fish species further north. These changes have contributed to bringing new attention to the Arctic, including from relative newcomers on the Arctic scene, such as China.

From monitoring threats above the horizon to Arctic Council cooperation

The Arctic received a lot of attention during the Cold War, as the North Pole represented the shortest route between the U.S. and the Soviet Union for bombers potentially carrying out a nuclear attack. In 1957, the U.S. and Canada created a binational organization, the North American Air Defense Command (NORAD)—renamed North American Aerospace Defense Command after 1981—to jointly anticipate and defend against air and space threats coming toward the North American continent. NORAD’s aerospace warning missions were supported by networks of radars stretching from Alaska to eastern Canada—the Defense Early Warning (DEW) line, which was replaced in 1985 with the more extensive North Warning System (NWS). The airspace above the Arctic was not the only source of concern: each side also feared the presence of submarines coming undetected under the ice cover. Yet even during the Cold War, the U.S. and the Soviet Union found opportunities to cooperate on some Arctic matters, for instance signing an Agreement on the Conservation of Polar Bears in 1973. In 1987, leader of the Soviet Union Mikhail Gorbachev launched the “Murmansk Initiative” to reduce the risk of potential confrontation in the Arctic and develop international cooperation on military and nonmilitary matters.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, the Arctic lost its strategic significance as a potential battleground between Washington and Moscow, and a sizable part of the military infrastructure that the Soviet Union had built in its Arctic region fell into disarray. Arctic nations turned their attention to “soft security” matters ranging from the protection of the Arctic environment to navigation safety. In 1996, the Ottawa Declaration established an Arctic Council with the eight Arctic nations as Permanent Members, as well as six organizations representing Arctic indigenous peoples as Permanent Participants. The purpose of the Council was to further Arctic cooperation on issues related to the environment and sustainable development and it has, over the years, led to the adoption of three international agreements on search and rescue (2011), marine oil pollution preparedness and response (2013), and scientific cooperation (2017). Economic issues are addressed through the Arctic Economic Forum, which was created in 2013. The high degree of international cooperation and peace in the Arctic even gave rise to the notion of “Arctic exceptionalism,” which describes a situation where Arctic matters manage to remain impervious to geopolitical tensions elsewhere in the world.

A rapidly transforming region attracts new interests

Since the mid-2000s, the Arctic has made a slow comeback as a region of strategic importance, as the result of several profound shifts. An increasingly ice-free Arctic means major transformations with regard to navigability; changed patterns in fishing; and new prospects for hydrocarbon exploitation and mining. These changes have focused increased scrutiny on the Arctic, and an interest that goes largely beyond Arctic nations. In response, the Arctic Council has progressively expanded, and as of 2020 13 non-Arctic states—China, France, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Poland, Singapore, Republic of Korea, Spain, Switzerland and the UK—had observer status in the Council.

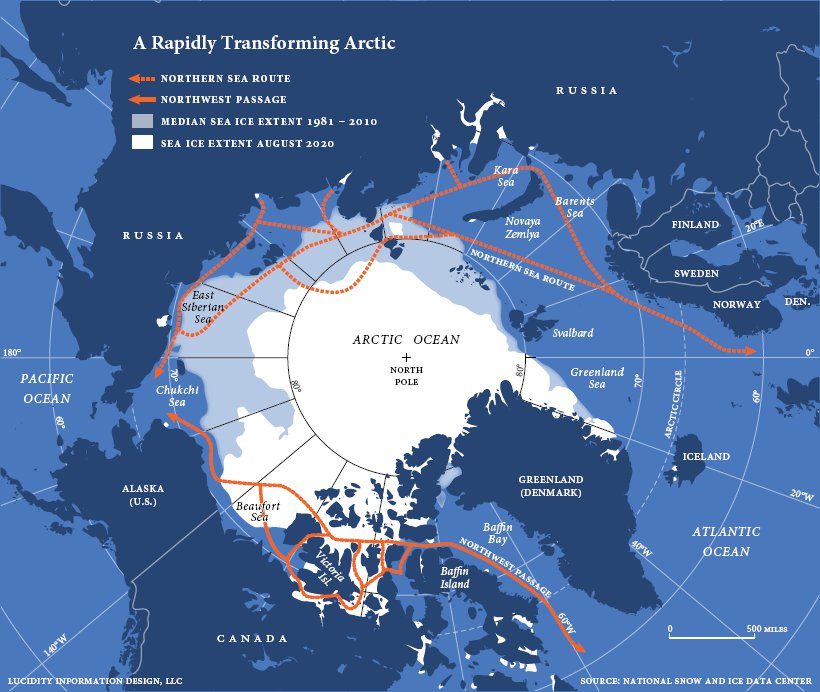

Sea ice melting results in an “opening” of the Arctic: some sea routes that were only navigable in the summer, or hardly navigable at all, can now be used for longer periods of time. In 2016, for the first time, a cruise ship with 1,700 people on board traveled along the Northwest Passage, across the Canadian Arctic archipelago. Along the northern coast of Russia, the Northern Sea Route represents a shorter route between Europe and Asia, cutting trips by several days and avoiding some potentially dangerous areas such as the Strait of Malacca. As of 2020, this shipping route was still more of a trickle than a highway: The Northern Sea Route Information Office recorded 27 transit voyages (mostly between Europe and Asia) in 2018, down from 31 voyages in 2014. Russia imposes a fee on ships navigating through the Northern Sea Route, and makes mandatory an escort by a Russian icebreaker. Navigation, while possible, is still not particularly easy. Chunks of melting sea ice make for treacherous waters, resulting in high insurance costs and voyages whose duration is still hard to predict. Yet as sea ice continues to disappear, so will these obstacles. In 2016, China issued a lengthy navigation guide specifically for the Northwest Passage, suggesting that it intends to make more use of this route in the future. Another major prospect for Arctic navigation is the expected opening of a third route that would cross over the Pole through the Central Arctic Ocean. This so-called Transpolar Route could be navigable by mid-century or even sooner, depending on climate models.

Climate change also has an impact on fisheries, with some species moving further north in search of cold water. Combined with a global decrease in fish stocks, this increases the attractiveness of Arctic fishing, and creates tensions among nations—including groups of nations, such as the EU—with regard to fishing quotas for species like mackerel. In other cases, cooperation prevails, as shown by the signing in 2018 of a moratorium on fishing in the Central Arctic Ocean. While there is no fishing yet in this area, which is still covered in sea ice, it is anticipated this will soon enough become a possibility due to the effect of climate change, thus requiring a “preemptive” moratorium.

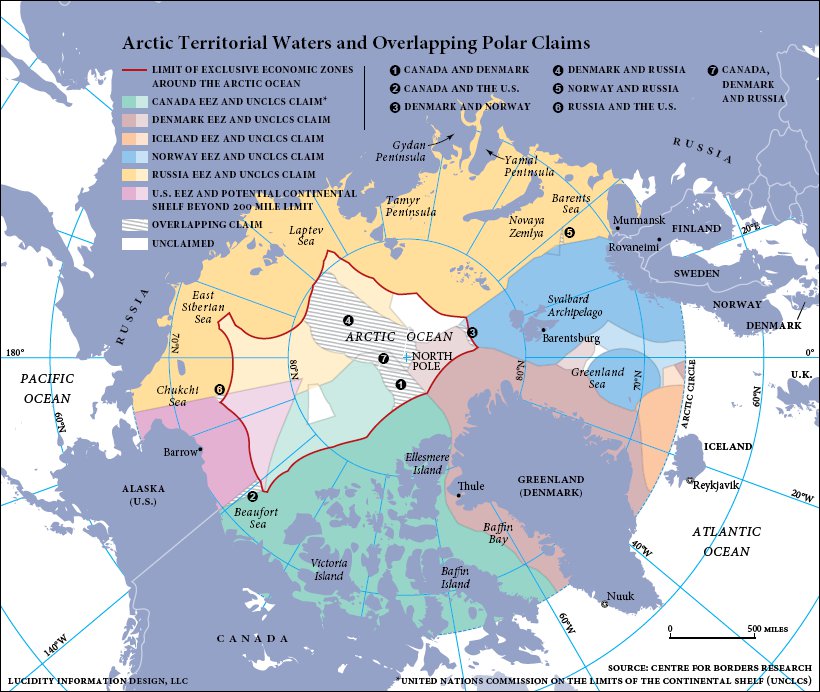

An ice-free Arctic is also an Arctic where it becomes easier to drill. In 2008, a U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) assessment described the Arctic as an immense reservoir of natural resources, noting that “90 billion barrels of oil, 1,669 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, and 44 billion barrels of natural gas liquids may remain to be found in the Arctic, of which approximately 84% is expected to occur in offshore areas.” Tapping into these reserves is a long-term prospect: The technological means to drill so deep and under such harsh conditions are not available yet, and there are plenty of more accessible sites closer to the coast that can still be exploited. It will be a long time before exploiting undersea Arctic gas or oil becomes technologically feasible and economically desirable. Yet this prospect explains in part why several Arctic states have submitted claims before the United Nations Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (UNCLCS) to gain recognition for a larger share of continental shelf. A state’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ), where it enjoys exclusive fishing, drilling, and mining rights, extends to 200 nautical miles beyond its coast. However, if a state can gather sufficient scientific evidence that the continental shelf beyond that limit is a continuation of the continental shelf within the 200 nautical miles, it can file a claim before the UNCLCS. In the case of overlapping claims from two or more states, the Commission’s recommendations on each claim becomes the basis for direct discussions between these states to decide on the limits of their continental shelves. When gaining such an extension of their continental shelf, states have access to the underground resources in the seabed and subsoil, such as minerals or hydrocarbons, but have no right to the column of water above it—for fishing or navigation, for instance—which remains international waters. As of 2020, there were several such claims under examination in the Arctic. Russia was the first in 2000 to submit one for an extensive area covering 1.2 million square kilometers, and comprising the North Pole. Russia revised and resubmitted its claim in 2015, after the UNCLS found the scientific evidence presented insufficient. Denmark submitted its own claim, which partially overlaps with Russia, in 2014. Canada was the last one to submit a third overlapping claim in 2019. The decision of the Commission might not be known for several years, and would in any case be only the prelude to negotiations between the three claimants.

What are U.S. interests in the Arctic?

After the Cold War ended, the Arctic largely lost its strategic significance for the U.S. Arguably, the U.S. always had a limited Arctic identity, owing solely to its purchase of Alaska from Russia in 1867. Most Alaskans live in the non-Arctic part of the state, and the notion that the U.S. is an Arctic nation does not come naturally to most Americans living in the so-called lower 48.

The Arctic started receiving more attention as the U.S. readied itself to take over the two-year rotating chairmanship of the Arctic Council in 2015. In 2013, the White House published a comprehensive Arctic Strategy, followed by an Implementation Plan in 2014. This Arctic Strategy emphasized three lines of effort: “Advance U.S. security interests;” “Pursue responsible Arctic region stewardship;” and “strengthen international cooperation.” The strategy also mentioned “safeguard peace and stability” and “consult and coordinate with Alaska natives” as two of its guiding principles to implement the strategy. In August 2015, U.S. President Barack Obama undertook an extended visit to Alaska, including north of the Arctic Circle. Under the U.S. Chairmanship, the Council successfully adopted an Agreement on Enhancing International Arctic Scientific Cooperation.

This renewed interest waned as U.S. political leadership changed and the U.S. passed the baton to Finland as the new Chair of the Arctic Council in 2017. The position of Special Representative for the Arctic, created in 2014 with the idea of having an “Arctic Czar” who could coordinate across agencies and support the U.S. Arctic Council Chairmanship was left unfilled. The Arctic Steering Committee, created by a presidential Executive Order in 2015 for a similar purpose, disappeared at the same time. In 2017, the White House published a new National Security Strategy that framed U.S. security objectives in relation to the “growing political, economic, and military competition we face around the world.” In that document the word “Arctic” is mentioned only once, as a “common domain” that should remain “open and free.” It is not mentioned in the unclassified synopsis of the National Defense Strategy published in 2018.

Russia’s Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov (2nd,L), Norway’s foreign minister Ine Eriksen Soreide (L)and Sweden’s foreign minister Margot Wallstrom (2nd,R)speak standing next to US secretary of state Mike Pompeo (R) while posing for a picture at the Arctic Council Ministerial Meeting in Rovaniemi, Finnish Lapland on May 7, 2019. (VESA MOILANEN/AFP/GETTY IMAGES)

Yet U.S. policy toward the Arctic experienced a significant turn in 2018–19, with the region becoming increasingly described as a theater of global strategic competition between the U.S. and its adversaries. In December 2018, Secretary of the U.S. Navy Richard Spencer suggested that the U.S. should conduct a freedom of navigation operation (FONOP) along the Northern Sea Route, to let Russia know that the U.S. considers it an international strait open to navigation, rather than internal waters that can be controlled by Russia. FONOPS are operations undertaken by the U.S. Navy according to the Freedom of Navigation Program, which was created in 1979 to counter what the U.S. calls “excessive maritime claims” that seek to deny other nations the ability to navigate freely in accordance with maritime international law. In May 2019, at the Arctic Council’s Ministerial Meeting in Rovaniemi, Finland, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo reaffirmed the Arctic identity of the U.S. and stated that “the region has become an arena for power and for competition,” mentioning explicitly China and Russia as sources of concern for the U.S. in the region. In August 2019, President Donald J. Trump’s reported interest in buying Greenland—a self-governing territory that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark—was another indication of the U.S. perception of the strategic importance of the Arctic. Other indications of this renewed interest include the release on June 9, 2020, by the White House of a Memorandum on Safeguarding U.S. National Interests in the Arctic and Antarctic Regions, which reaffirmed the U.S. decision to equip itself with a new fleet of icebreakers. This effort is already underway with the Coast Guard Polar Security Cutter program, which, as the Congressional Research Service notes in its reportabout the program, received $100 million more in funding from Congress in fiscal year 2020 than what had been requested. Still in June 2020, the U.S. reopened its consulate in Nuuk, Greenland, which had been closed since 1953, and in July 2020, the State Department appointed a U.S. Coordinator for the Arctic Region. The U.S. is not just signaling its interest in the Arctic; it is also doing so at an increasingly rapid pace, and through a whole-of-government approach that underlines the military, economic, and diplomatic importance of the Arctic.

The Prirazlomnaya offshore ice-resistant oil-producing platform is seen at Pechora Sea, Russia, on May 8, 2016. Prirazlomnaya is the world’s first operational Arctic rig that process oil drilling, production and storage, end product processing and loading. (SERGEY ANISIMOV /ANADOLU AGENCY/GETTY IMAGES)

Who is the U.S. competing against in the Arctic?

The U.S.’ renewed interest in the Arctic is largely prompted by a concern that Russia and China are using the region to increase their political, economic, and military influence. Yet Russia and China have different stakes in the Arctic, which present different challenges for the U.S.

Russia has long seen its Arctic region as strategically important, for several reasons. The first is economic: the Russian Arctic holds important oil and gas reserves, which are essential to a Russian economy largely dependent on the exploitation of hydrocarbons. Russia is looking at its Arctic region to become a major liquified natural gas producer. The large-scale LNG plant and terminal in the Yamal Peninsula that Russia built partly with foreign investment (mostly Chinese) became operational in 2017, and another LNG project (Arctic-LNG 2) is under development on the nearby Gydan Peninsula. This makes the Northern Sea Route a major economic artery of Russia, particularly as it becomes increasingly navigable. Russia controls this route tightly for economic but also security reasons, as its northern border gradually loses the ice that used to form a natural defense. Russia’s Arctic, and more specifically the Kola Peninsula, is also where an estimated two thirds of Russia’s strategic deterrent is located. Russia seeks to protect this area through a “bastion” strategy that includes a dense network of air and coastal defenses.

Three issues in particular represent potential sources of tension between the U.S. and Russia. One is the progressive remilitarization, by Russia, of its Arctic region. In 2015, Russian Defense Minister Sergey Shoigu argued that preserving Russian national security required, among other things, a “constant military presence in the Arctic,” and Russia has devoted substantial financial resources to reach that objective. Russia has refurbished or modernized Soviet-era bases and airfields and built new infrastructure, particularly along the Northern Sea Route. It established a dedicated northern command for the region, created two Arctic brigades—one of which is located close to the Finnish border—and is planning to increase its already large icebreaker fleet. Russia is also heavily investing in its navy, particularly submarines, with a focus on the Northern Fleet.

A second source of tensions is the increased Russian military presence in the maritime areas between Greenland and Iceland, and between Iceland and the UK (the so-called “GIUK gap”). The GIUK gap represents Russia’s gateway to the North Atlantic for its Northern Fleet based out of Murmansk. The U.S., the United Kingdom, and Norway are increasing their efforts to monitor the area, particularly for submarine activity. The U.S. renovated the Keflavik airbase in Iceland, which it had left in 2006, in order to conduct maritime air patrols in the region.

Finally, the U.S. contests Russia’s policy of exerting strict control over the vessels that navigate through the Northern Sea Route. Russia argues that Article 234 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) provides states with extended control over vessels navigating through ice-covered areas in order to prevent maritime pollution, which would be particularly devastating in such areas. The U.S. claims that this interpretation violates the freedom of navigation principle, and warned Russia that it might conduct freedom of navigation operations in that area, taking a first step in that direction with a joint U.S.-UK exercise in the Barents Sea in May 2020.

China, meanwhile, is expressing increasing interest in the Arctic. In its first Arctic policy published in January 2018, China describes itself as a “Near Arctic State,” an unusual term that characterizes, according to the policy, “one of the continental States that are closest to the Arctic Circle.” China’s interest in the poles is not a new phenomenon. It has conducted scientific activity in Antarctica since the 1980s and established a first research station in the Arctic, on Svalbard, in 2004. A key motivation for this scientific activity is studying global climate change, which will have a dramatic impact on China’s coastal cities and economy in particular. China’s interest in the Arctic, however, goes well beyond scientific research, as its Arctic policy describes a future “Polar Silk Road” integrated to its larger Belt and Road Initiative. China is interested in investments in oil and gas exploitation, mining (particularly for uranium and rare earth minerals, which are essential to various new technologies), fisheries, and shipping. A November 2017 Center for Naval Analyses (CNA) study found that China’s investments in Arctic littoral states were highest in Greenland when calculated as a percentage of the national GDP (11.6% over the time period 2012–17). China is also, after Russia, a relatively important user of the Northern Sea Route, with eight transit voyages in 2018, according to transit statistics from the Northern Sea Route Information Office, out of 19 voyages conducted under a non-Russian flag.

In his 2019 speech at the Arctic Council, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo highlighted various U.S. concerns with regard to an increased Chinese presence in the Arctic. First, he questioned China’s ability to respect the rules of the game, pointing to “China’s pattern of aggressive behavior elsewhere,” and thus suggesting that higher economic and financial stakes in the Arctic could allow China to impose its own rules, similar to how it applies its interpretation of maritime international law in the South China Sea. A second concern is the political influence that China might gain in the Arctic thanks to its new economic weight, particularly if countries accepting Chinese investments were to find themselves unable to pay back their loans. China may thus gain a foothold in areas—such as Greenland—that the U.S. sees as important strategically. A third concern is China’s potential ability to turn its economic activity into military presence, with Secretary Pompeo arguing that “This is part of a very familiar pattern. Beijing attempts to develop critical infrastructure using Chinese money, Chinese companies, and Chinese workers—in some cases, to establish a permanent Chinese security presence.” According to this view, the infrastructure that China is seeking to build as part of a “Polar Silk Road” might be used not just for civilian but also military purposes. The same might be said of some of China’s scientific research outposts. China’s construction of an observatory for northern lights in Iceland, for instance, has raised concerns that the facility might be used for intelligence gathering purposes rather than scientific research.

Echoing some of these concerns, the response from Arctic nations to Chinese investments has so far been mixed. In 2013, Iceland signed with China a free-trade agreement—the first one ever signed by China with a European nation—yet one year earlier Iceland had also blocked the possible sale of a large plot of land to a Chinese investor, who intended to turn it into a luxury hotel and golf resort. A similar deal fell through in Svalbard, which is governed by Norway, in 2016. Still in 2016, Denmark objected to the sale of a vacant naval base in Greenland to a Chinese mining company. In 2018, after Greenland shortlisted a Chinese company to build two airports, the U.S. expressed concerns to Copenhagen, which stepped in to fund the project instead. Yet Chinese investments are also attractive to Arctic economies that are in dire need of job prospects and infrastructure.

Acting Murmansk Region Governor Andrei Chibis (R) greets oil workers at the Nanhai VIII semi-submersible drilling rig in the Kola Bay. (LEV FEDOSEYEV/TASS/GETTY IMAGES)

U.S. foreign policy in the Arctic

The U.S. has close allies and partners in the Arctic. Three U.S. NATO allies in particular stand out based on history and recent U.S. policy developments: Canada, Denmark, and Norway. Canada has a long history of defense cooperation with the U.S., and represents a first line of defense for the North American continent for potential threats coming from the Arctic; the U.S. is increasingly involved in Greenland, due to its strategic location between the Arctic and the Atlantic; and Norway, which borders Russia, is also strengthening its defense relationship with the U.S. and supports NATO’s involvement in the region.

Canada

U.S close cooperation with Canada in the Arctic continued after the collapse of the Soviet Union, with NORAD maintaining its relevance in the post-Cold War era. In the immediate aftermath of 9/11, Operation Noble Eagle gave NORAD’s commander new responsibilities regarding the protection against the threats represented by aircraft within the U.S. and Canada. In 2006, a third mission—maritime warning—was added to NORAD’s aerospace warning and aerospace control missions. In 2012, the U.S. and Canada signed a Tri-Command Framework for Arctic Cooperation designed to increase their joint activities in domains such as domain awareness, exercises, information sharing, and scientific cooperation in the Arctic. The two countries regularly conduct joint exercises, such as the annual Vigilant Shield exercise, which focuses on increasing their ability to protect their homelands from incoming threats, or the biennial ICEX naval military exercise that trains Canadian and U.S. submariners to operate in the Arctic. Upcoming challenges for NORAD include the modernization of the aging North Warning System, which is due for update or replacement around 2025.

The U.S. and Canada still disagree on Canada’s official definition of the Northwest Passage—the maritime route that runs along Canada’s northern border—as “internal waterways.” Canada closely controls the Passage through its Northern Canada Vessel Traffic Services Zone regulations, and every ship that transits the passage must register with the Canadian Coast Guard. Like Russia, Canada justifies its position on the basis of Article 234 of UNCLOS, even as the passage becomes increasingly ice-free. Canada and the U.S. have generally agreed to disagree on this issue, but this position might become less tenable as the U.S. becomes increasingly vocal against Russia’s own interpretation of Article 234 as it relates to the Northern Sea Route.

Denmark/Greenland

Denmark is an Arctic nation thanks to Greenland, which is part of the Kingdom of Denmark but has the status of a self-governing territory. It thus decides on its own laws, except in the domains of foreign policy and defense, which are still decided by Copenhagen. Greenland made the headlines in August 2019 when it was made public that President Trump was considering that the U.S. purchase it. Its strategic value for the U.S. stems from its position at one end of the GIUK gap. With the rise of a more militarily assertive Russia, Thule Air Base, in Northwestern Greenland, has also regained some of the importance it had during the Cold War, and the U.S. Air Force Arctic Strategy published in July 2020 notes that “Locations like Clear, Alaska and Thule, Greenland uniquely enable missile warning and defense in addition to space domain awareness.”

U.S.-Greenlandic relations have experienced several important developments. In addition to reopening its consulate in Nuuk, the U.S. announced in 2020 that it would provide Greenland with $12.1 million in development aid for various projects related to renewable energies, fisheries management, and tourism. U.S. growing interest in Greenland requires it to navigate a complex trilateral relationship with Nuuk and Copenhagen. Copenhagen still provides a block subsidy to Nuuk that is calculated annually based on different factors and covers a large share of Greenland’s expenses, thus contributing to keeping Greenland within the Kingdom of Denmark.

Norway

Norway’s Finnmark region borders Russia, and the two countries’ bilateral relations in the Arctic have generally been cooperative. They have worked together since 1993 in the Barents Euro-Arctic Council, which supports coordination across the Barents region; they finally resolved in 2011 their 40-year old disagreement on their respective boundaries in the Barents Sea; and their Coast Guards routinely cooperate, including through joint exercises, to improve their ability to do effective search and rescue in their territorial waters and beyond.

Yet Norway is also seeing with some concern Russia’s remilitarization of its Arctic region, and has advocated for a NATO presence in the Arctic. In 2017, Norway invited 300 U.S. marines to deploy a rotational presence on its territory with the purpose of training them for cold weather warfighting. The size of the rotation was increased to 700 a year later. In October and November 2018, Norway hosted Trident Juncture—a large-scale NATO exercise that gathered approximately 50,000 personnel from 31 NATO members and partner countries. In parallel, incidents with Russia have become more numerous over the years. On several instances Russia has engaged in the jamming of GPS signals and military communications to disrupt Norway’s exercises. Other incidents include Russia carrying out simulated attacks against Norway’s radar in Vardø, close to the Norway-Russian border, on at least two occasions in 2018 and 2019.

Norway also watches closely activity on and near the Svalbard Archipelago, located roughly halfway between the North Pole and northern Norway. Svalbard’s legal status is unusual. The Svalbard Treaty (or Spitsbergen Treaty) signed in 1920 recognizes Norwegian sovereignty but also authorizes the treaty’s 46 signatories to conduct commercial activities on the islands. About a fifth of the archipelago’s population lives in Barentsburg, which is a Russian settlement established around a coal mine that is still in use. Norway and Russia have regularly clashed, over the years, on the status of the waters around Svalbard. Since the treaty does not formally extend Norway’s governance to the waters around Svalbard, Norway has established a Fishing Protection Zone (FPZ) around the archipelago rather than the more common Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), but Russia has consistently contested Norway’s authority over that FPZ.

U.S. policy in the Arctic: what next?

As the U.S. becomes more committed to playing an active role in the Arctic, it faces a number of policy decisions. Two broad issues, in particular, will require the attention of decisionmakers in the years to come. One relates to the amount of resources that the U.S. is ready to devote to this region. Another relates to how the U.S. can be part of Arctic institutions’ evolution, to ensure that they can meet emerging challenges.

The U.S. has long suffered from a lack of Arctic-specific capabilities, such as icebreakers. Without such assets, freedom of navigation operations along the Northern Sea Route, which is much more hazardous than the Barents Sea, will remain an empty threat, or could lead to an embarrassing situation where the U.S. attempts a failed show of force. The U.S. has long managed with a minimal float of one medium icebreaker, the Healy, and two heavy ones, the Polar Star and the Polar Sea. The only reason that the Polar Star can be at sea is because it cannibalizes the Polar Sea—which has been out of commission since 2010—for spare parts when needed. Even then, the Polar Star, which has been operational since 1976, is long past its 30-year life expectancy. Use of the Polar Star for Arctic requirements is limited by the fact that it is also needed to resupply U.S. scientific stations in Antarctica. The Polar Security Cutter program represents an important step toward remediating this situation. How the U.S. sustains this program and addresses other identified needs such as the creation of a deep port in northern Alaska, will play an important role in ensuring that it has the means of its ambitions in the Arctic.

Paratroopers from the Chaos Troop, 1st Squadron (Airborne), 40th Cavalry Regiment, participate in U.S. Northern Command’s Exercise Arctic Edge 20 at the Donnelly drop zone at Ft. Greely, AK, Feb. 29, 2020. The exercise focuses on training, experimentation, techniques, tactics, and procedures development for Homeland Defense operations in an Arctic environment. (U.S. AIR FORCE PHOTO BY STAFF SGT DIANA COSSABOOM)

A second challenge is keeping the Arctic at peace and maintaining the type of international cooperation that has benefitted all Arctic nations so far. At the 2019 Arctic Council meeting in Rovaniemi, Finland, Arctic nations for the very first time failed to agree on a common declaration at the end of the summit, because the U.S. refused to include in the text any reference to global warming. This could be the sign of a new era where bilateral relations—for instance, between the U.S. and Greenland—take precedence over multilateral institutions. Yet some of the greatest advancements in the rules-based order in the Arctic have come from effective concertation between all Arctic nations in forums such as the Arctic Council. How these institutions will evolve represents another issue. The use of the Arctic Council, by U.S. Secretary of State Pompeo, to discuss the security risks posed by Russia and China in the Arctic, is a reminder that there was no security-specific Arctic forum that might have been more appropriate. Various options have been proposed to address this issue, including reestablishing the defunct meeting of the Arctic Chiefs of Defense Staff, which was suspended in 2014. Whether security issues can successfully be integrated in Arctic discussions will become increasingly critical as Arctic and non-Arctic states become more concerned with the return of “hard security” issues in the region. Finally, another challenge relates to the role that non-Arctic countries can expect to play in Arctic forums. For the U.S., this presents a dilemma. Broad inclusion is consistent with the U.S. view of the Arctic as a “common domain,” as expressed in the 2017 National Security Strategy. Yet Secretary of State Pompeo’s statement in Rovaniemi that “There are only Arctic States and Non-Arctic States. No third category exists, and claiming otherwise entitles China to exactly nothing,” makes clear that the U.S. believes it has stakes in Arctic governance that China does not have. How the U.S.—and other Arctic nations—take into account the interests and concerns of non-Arctic nations will play a key role in defining Arctic institutions for years to come and ensuring that their own interests are preserved in this increasingly important strategic region.

discussion questions

1 Should countries that are part of the Arctic council prioritize policies that would attempt to limit the melting of ice? Do the economic benefits outweigh the environmental ones?

2. Why has the United States been a “reluctant” Arctic nation in the past?

3. How much should the United States government spend towards increasing the U.S’ influence and capacity in the Arctic?

4. What could be some of the negative effects should the Arctic become another point of contention between the U.S. and China? Can the U.S. look to use the region as a potential source of cooperation with China?

suggested readings

Laruelle, Marlene. Russia’s Arctic Strategies and the Future of the Far North. Routledge. 280 pgs. 2013. An expert overview of Russia’s stakes in the Arctic, based on an analysis of its history, politics, demographics, and economics. It examines in detail the domestic determinants of Russia’s Arctic policy, as well as its efforts to project diplomacy as well as, potentially, power. A chapter on “Climate change and its expected impact on Russia” gives a useful perspective on the upcoming challenges that Russia will face, and how they might impact its Arctic policy.

Boulegue, Mathieu. Russia’s Military Posture in the Arctic Managing Hard Power in a ‘Low Tension’ Environment. Chatham House. 46 pgs. 2019. A comprehensive review of Russia’s military capabilities and activities in the Arctic.

Klimenko, Ekaterina and Sorensen, Camilla T. Emerging Chinese-Russian Cooperation in the Arctic. Sipri 56 pgs. 2017. The paper combines expert knowledge of China’s and Russia’s role in the Arctic to identify the various interests that the two countries might share, as well as existing and potential points of friction. Their analysis concludes on the limits of this cooperation, providing a useful corrective to the often heard notion that Russia and China will join forces and empower each other in the Arctic.

The Arctic Yearbook is published online and gathers contributions from Arctic experts around an annual theme. The 2019 Yearbook, edited by Lassi Heininen, Heather Exner-Pirot, and Justin Barnes, focuses on “Redefining Security in the Arctic” and offers a broad view of the different meanings of “security” in the Arctic, looking at military, socio-economic, health, and sustainable development issues

Berry, Dawn Alexandrea, Bowles, Nigel and Jones, Halbert. Governing the North American Arctic: Sovereignty, Security, and Institutions. Palgrave Macmillan 288 pgs. 2016. This book focuses on the North American part of the Arctic that includes the United States and Canada, and extends all the way to Greenland. Contributions include, among others, an exploration of the “Arctic identity” of Canada and the United States, an analysis of Chinese mining activities in the region, and an overview of the long history of cooperation between Canada and the United States on Arctic matters.

Osthagen, Andreas, Sharp, Gregory Levi and Hilde, Pall Sigurd.. “At Opposite Poles: Canada’s and Norway’s Approaches to Security in the Arctic,” The Polar Journal, Vol.8, No. 1, 2018.

Don’t forget: Ballots start on page 104!!!!

To access web links to these readings, as well as links to global discussion questions, shorter readings and suggested web sites,

GO TO www.fpa.org/great_decisions

and click on the topic under Resources, on the right-hand side of the page.