by Cobus van Staden

COBUS VAN STADEN is a Senior China-Africa researcher at the South African Institute of International affairs. He also is the head of research and analysis at the China-Africa Project, and co-host of the China in Africa Podcast.

! Before you read, download the companion Glossary that includes definitions, a guide to acronyms and abbreviations used in the article, and other material. Go to www.fpa.org/great_decisions and select a topic in the Resources section. (Top right)

A group of performers hold Chinese and Ivorian flags during the inauguration ceremony of Ivory Coast’s new 60,000-seat Olympic stadium, built with the help of China, in Ebimpe, outside Abidjan, on October 3, 2020 ahead of 2023 Africa Cup of Nations. (IISSOUF SANOGO/AFP/GETTY IMAGES)

China’s relationship with Africa can’t be separated from the continent’s own fraught history. While the Ming-era Chinese commander Zheng He visited the East African coast in 1413, the modern relationship dates back to Africa’s anti-colonial struggle and the formation of the non-aligned movement in Bandung, Indonesia, in 1955. At that moment, China had just achieved its own communist victory, and Africa was struggling against both European colonial occupation and broader Western attempts at neo-colonial control.

China emerged as a prominent supporter of Africa’s anti-colonial struggle during this era, particularly after its relations with the Soviet Union soured and then-Premier Zhou Enlai toured the African continent during the early 1960s. This phase lasted roughly until the death of Mao Zedong in 1976, and while China’s subsequent relationship with Africa was very different, this early era set some parameters that have structured the relationship to this day. In the first place, Zhou articulated a set of principles that still defines Chinese foreign policy with African countries (and further afield). These include the principle of non-interference in the domestic affairs of partner countries – still a controversial cornerstone of Chinese foreign policy, in that it opens China to criticism that it supports authoritarian governments. In the second place, while Chinese support and training of anti-colonial armies is a remnant of the cold war, South-South solidarity, and narratives of shared victimization by Western powers remain prominent tropes in China-Africa diplomacy. In the third place, one instance of China’s assistance to Africa set the template for much future cooperation: The TAZARA railway.

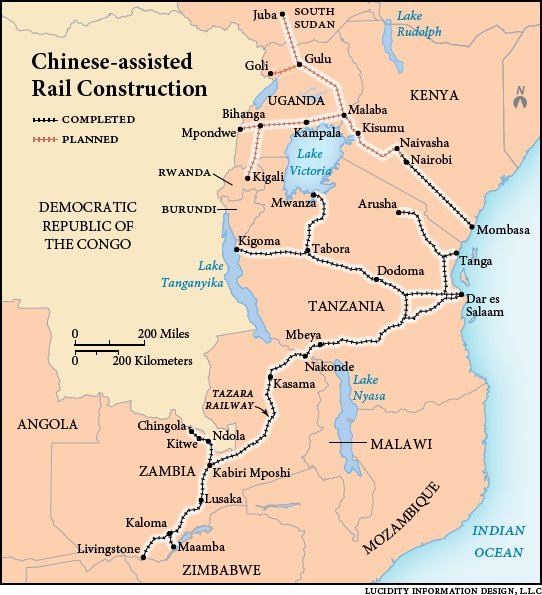

The TAZARA railway was a response to a key problem still facing Africa: the lack of cross-border infrastructure. In the late 1960s, Zambia, a land-locked country, was desperate to get its copper exports to the global market. Its only access to a port was controlled by two hostile entities: colonial Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and apartheid South Africa. China provided funding and personnel to construct an 1,860 kilometer line to Tanzania, undercutting the stranglehold of neo-colonial forces in Southern Africa, and providing a potent symbol of South-South cooperation. The railway also set the template for a key area of later China-Africa cooperation: infrastructure.

President Kenneth Kaunda (left of the two men) of Zambia and President Julius Nyerere (1922–1999, right) of Tanzania rest their feet on the sleepers of the new Great Uhuru Railway (later the TAZARA Railway), which links their two countries, during the halfway celebrations at Tunduma on the border, September 6, 1973. The railway was a joint venture between the two countries, financed by China. (KEYSTONE/HULTON ARCHIVE/GETTY IMAGES)

The TAZARA railway was finished in 1975, almost at the end of Mao Zedong’s reign. During the early days of China’s subsequent Reform and Opening Up era, engagement with Africa waned, in favor of domestic development and the courting of foreign direct investment from Japan, the U.S. and Europe. It was a very different China that returned to Africa in the 1990s.

China’s return to Africa was spurred by the temporary freeze in its relations with Western powers following the crackdown in 1989 on pro-democracy protesters in Tiananmen Square in Beijing. The sudden diplomatic clampdown provided the impetus to look for other external partners. However, the main driver for outreach was Deng Xiaoping’s Go Out strategy, which urged China’s state-owned enterprises to find external markets and sources of commodities. Chinese companies initially focused on the extractives sector, trying to secure oil and other resources for the country’s booming manufacturing sector. African countries, many still reeling from a series of structural adjustments imposed by the Bretton Woods institutions, were glad for the business. The result was the rapid increase in China-Africa trade and other engagement during the 1990s, which set the scene for the formalization of the relationship at the end of the decade.

Forum on China-Africa Cooperation

Arguably the most important development in the China-Africa relationship was the establishment of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC). It facilitated the evolution from a rapidly growing set of ad hoc relationships, to a formal platform for cooperation. The first FOCAC meeting took place in 2000, in Beijing. Since then, it has taken place regularly every three years, alternately in Africa and in China. Initially it took place at a ministerial level, but it has been frequently elevated to the summit level (attended by heads of state.) The formalization of the relationship also allowed its expansion from a relatively narrow commercial relationship to a far more comprehensive one covering many forms of cooperation.

At the beginning of the relationship, China was already a major provider of financing to the continent. FOCAC helped to expand and centralize this role. FOCAC meetings became the occasion for the announcement of increasingly ambitious funding targets, covering several areas of cooperation, of which infrastructure was a major one. In 2006, in Beijing, the first time FOCAC took place at the summit level, the Chinese government announced $5 billion in concessional loans to Africa. In 2009, in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, this was increased to $10 billion. By 2012, in Beijing, it grew to $20 billion, and then $60 billion in Johannesburg, South Africa in 2015. The same sum was again announced at the 2018 summit in Beijing. In addition, the 2006 summit also saw the establishment of the China-Africa Development Fund, with a capitalization of $1 billion, which was increased to $5 billion at the 2012 summit in Beijing.

These numbers are shorthand for complex packages of different financing instruments. For example, the allocation of $60 billion that was announced in 2015, included $5 billion in aid and interest-free loans, $35 billion in export credits and concessional lending, $5 billion of additional capital to the China-Africa Development Fund, another $5 billion as a Special Loan for the Development of African Small and Medium Enterprises, and $10 billion in capitalization for a China-Africa Production Capacity Cooperation Fund.

What this breakdown makes clear is that China differs from other development partners in that most of its development assistance comes in the form of loans, rather than grants. The division is less between loans and grants, than between different kinds of loans, with a small fraction coming in the form of interest-free loans and the majority in the form of concessional lending, which forces lenders to pay interest, albeit at lower than global market rates.

There are a few important details to keep in mind. In the first place, the condition for participating in FOCAC is that a country should have diplomatic ties with China. These ties are dependent on accepting the One China Principle, which makes it impossible to simultaneously maintain relations with Taiwan, which China sees as a separatist province. Through the decades, Taiwan had established diplomatic relations with several African countries, but the rise of China as a major development partner has also led to the erosion of these ties. Currently only one African country, eSwatini (formerly known as Swaziland), still has ties with Taiwan, and for that reason it is the only African country that doesn’t participate in FOCAC.

In the second place, while FOCAC comes across as a platform for the whole African continent to engage with China collectively, it is actually structured as a large number of bilateral relationships between various African countries and China. While China also maintains diplomatic relations with the African Union, and has pledged cooperation with this body, as well as committing itself to multilateral cooperation on issues like peacekeeping, the China-Africa relationship is more accurately described as a series of relationships. This focus on bilateral relationships means that China far outstrips its African partners in both economic and political power. This power imbalance has led to numerous calls from observers for greater collectivity in African countries’ negotiation with China, which has so far not been realized.

However, African countries have managed to use FOCAC as a mechanism to address continental priorities. While China’s focus in FOCAC started off relatively narrowly, with a main focus on infrastructure and resources, African pressure has ensured that several other issues have been added to the agenda. Over time, FOCAC has been expanded to include a greater focus on peacekeeping. This was especially true from 2012, after which China sent peacekeeping troops to African countries like Mali and South Sudan under the auspices of the United Nations, and participated in patrols off the coast of East Africa, which has significantly lessened the threat of piracy to international vessels. African countries also put pressure on China in the context of FOCAC to focus more on wildlife crime. The rapid expansion of prosperity in China has led to a growing demand for rare wildlife products like ivory and rhino horn. This fueled a poaching economy in Africa, which led to the rapid decline of wild animal populations and the eruption of illegal trade driven by criminal syndicates. Pressure from African countries arguably led to the implementation of a Chinese ban on the domestic trade in ivory in 2015, a major victory for African conservation.

Then-Chinese Vice-President Xi Jinping delivers a speech during the 10th anniversary of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) on November 18, 2010, in Pretoria, South Africa. (PABALLO THEKISO/AFP/GETTY IMAGES)

Finally, African countries also managed to secure much more robust commitments to training and skills transfer. The lack of broad-based skills is one of the largest challenges facing African development. The continent’s population is very young – the average African is only 19 years old. While this youth dividend holds significant promise for African development, the relative lack of training facilities is a challenge. Chinese training, boosted by high-level diplomatic facilitation at the FOCAC level, has proven a major area of cooperation. Currently, tens of thousands of Africans receive training in China. China has recently surpassed France as the most important destination for African students, and currently hosts more African students than the U.S. and the UK combined.

This training happens in many forums at once. In the first place, the Chinese government grants thousands of scholarships to African students to study at Chinese universities. In addition, many African students also self-fund their studies in China. The establishment of Confucius Institutes at African universities has facilitated this process. These bodies, akin to France’s Alliance Française, provide language and cultural instruction. They have proven controversial in the U.S., where they have been characterized as state-sponsored propaganda and influence-building tools. While similar concerns exist in Africa, African universities don’t have many other ways to offer their students Mandarin-language education, which is highly sought after.

In addition to university education, training also happens via Chinese companies. For example, technology companies like Huawei frequently send employees to train in China. Training also happens at the government level. Thousands of government employees are trained in China every year in a variety of disciplines, from public administration to anti-corruption. Members of some ruling parties (for example South Africa’s African National Congress) also receive political training from counterparts in the Chinese Communist Party.

Finally, the police and military have emerged as major vectors for skills transfer. Training of military and police personnel in everything from weapons systems to crowd control has functioned as a basis for closer relationships between bodies like the People’s Liberation Army and various African militaries, a process boosted by numerous exchange visits and joint exercises. One example of the latter is triangular naval exercises that took place between China, South Africa and Russia in 2019.

From the African side, this training helps to fill serious skills deficits. It also has the wider implication of building relations between numerous African and Chinese institutions, from the state, to the province, to the school level. These relations will have a lasting impact. In the first place, training leads to the implementation of Chinese technical standards and methodologies in Africa, which will cement maintenance and upgrade relationships going forward. In the second place, Chinese universities are under much pressure to conform to current thinking within the Chinese Communist Party on a variety of issues. This thinking is also transferred to African students and trainees. In the third place, the widespread training will have the effect of building long-term relationships between African elites and China, helping to shape their worldviews and providing a shared linguistic and cultural framework linking members of various African elites through shared time in China. The long-term impact of this training will be to build longer-term Chinese influence in Africa, even as Western governments make it harder for Africans to study at institutions in the U.S., Europe and the UK.

Overall, FOCAC provided crucial impetus to the China-Africa relationship. In the first place, it framed and supported the commercial China-Africa relationship. China became the continent’s largest trading partner in 2009, a position it still holds today. It is now the largest bilateral lender to many of Africa’s largest economies, and Chinese companies are reshaping skylines across the continent. FOCAC was a crucial factor boosting the growth of this relationship. It didn’t only provide a platform for massive amounts of financing, it also provides a forum for diplomacy. The optics of crowds of African leaders arriving to greet President Xi Jinping, and the opportunity to reiterate diplomatic talking points, mean that FOCAC plays a major role in selling the China-Africa relationship to publics on both sides. In the process, it allowed the blossoming of many areas of cooperation, as outlined below.

Current issues defining the China-Africa relationship

Infrastructure

Infrastructure remains one of Africa’s most pressing needs. Deliberate underdevelopment under European colonialism, and these powers’ focus on extraction from the hinterland, rather than connecting domestic economic centers have proven a major reason for the continent’s continued poverty. The chaotic decolonization process, which was frequently only achieved through long civil conflict, the tendency for some colonial powers to abruptly withdraw without transition plans, a debt crisis and the subsequent impact of structural adjustment programs imposed by the Bretton Woods institutions in the 1980s and 1990s, corruption, and ill-designed national development plans have all contributed to a massive lack of infrastructure. The African Development Bank has estimated that the continent needs to spend between $130 and $170 billion per year to close this gap.

The lack of cross-border infrastructure is a particularly glaring problem. The World Bank has estimated that it costs less to ship a car from Japan to Kenya, than it does to get it from Kenya to Nigeria. There is currently no major roadway or railway connecting East and West Africa. This means that, in the World Bank’s example, the car would have to travel highly circuitous and inefficient routes, which will take time and cost money. In addition, it will also have to clear customs several times on the way, as it moves across different borders. The customs duties paid at each border will add significantly to its price by the time it reaches the Nigerian market.

For all of these reasons, African intra-continental trade stands at 15% of its total trade – the lowest continental rate in the world. Compare this to the European, where some member states’ trade with their neighbors make up to 70% of their total trade, significantly boosting the prosperity of the bloc as a whole. Africa is rapidly moving to change this, particularly through its African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA), agreed in 2019.

The lack of cross-border infrastructure is a big challenge to the implementation of the AfCFTA. In addition, the relative scarcity of ports, ICT networks, industrial infrastructure and stable electricity supplies all make it harder for African countries to link themselves to the global economy and to attract foreign direct investors. Amid these challenges, China has emerged as the continent’s most important provider of infrastructure. The reason for this has much to do with domestic concerns within China.

First, the Chinese government (as part of its Going Out strategy) has encouraged Chinese state-owned enterprises to explore the global market. This expansion drew heavily on China’s own experience of development, which was significantly infrastructure-driven. Within a few decades, China has multiplied its own infrastructure, with rail, ICT and road networks expanding across its territory at break-neck speed. This process made Chinese state-owned construction companies the repositories of massive technical resources, and the Going Out strategy increased pressure on them to apply these skills elsewhere. They were made considerably more competitive through their relatively easy access to funding from Chinese state banks, like the China Exim Bank. In addition to the FOCAC-directed funding mentioned above, these banks have funneled billions of dollars of additional funding to African infrastructure projects, in the form of loans. This aid is tied, which means that it is dependent on recipient governments employing Chinese contractors, a factor which further boosts Chinese companies’ foreign expansion. This process has received significant further momentum from the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)

These factors have contributed to Chinese actors transforming skylines in many African cities. In many cases, this infrastructure took the form of showcase standalone projects—bridges, soccer stadiums, parliament buildings, mosques and power stations. However, in some cases, these have also boosted the implementation of Chinese models of development through infrastructure, for example via so-called “Port-Park-City” projects (see the section on Development Models below).

Some of these projects have also included cross-border connectivity. Kenya’s Standard Gauge Railway was a key example, revealing some of the complications involved. In its original design, the SGR was supposed to link several East and Central African countries with the Kenyan port of Mombasa. The initial section of the railway, between Nairobi and Mombasa was finalized in 2017, with a second section, between Nairobi and an inland freight center in Naivasha, completed in 2019. The third section, which was supposed to connect Naivasha to Malaba on the Ugandan border, was supposed to then extend to the Ugandan capital of Kampala, and from there to Kigali in Rwanda, and Juba in South Sudan.

The initial two phases cost $3.8 billion and $1.5 billion respectively. 90% was funded through loans from the China Exim Bank to the Kenyan government, with the remainder directly funded by Nairobi. However, when President Uhuru Kenyatta travelled to Beijing in 2019 to secure the third loan that would connect Naivasha to Uganda, Chinese authorities refused, and he was forced to return empty-handed. It was an early indication that Beijing was worried about the financial sustainability of the SGR. In Kenya, the high cost of the project (compared to a similar Chinese line between Addis Ababa and Djibouti, and a Turkishbuilt line in Tanzania, both significantly cheaper) was extremely controversial, and investigations showed that the loan had been inflated by corrupt officials, enabled by the pervasive secrecy that shrouded the loan negotiations (see the section on Debt, below.) At the same time, while the Nairobi-Mombasa line proved popular among passengers, projections of freight profits from the line proved inflated. At present it is still unsure whether the planned connections with Uganda and other countries will be built, and whether the Kenyan section of the SGR will ever be profitable. As the Covid-19 pandemic, and its subsequent economic crisis hit, Kenya’s debt burden has become more worrisome, with the country now in significant danger of debt distress.

Debt

Chinese institutions like the China Export Import Bank and the China Development Bank have emerged as major financers of new African infrastructure. The vast majority of this finance comes in the form of loans. Unlike many other financing partners, China does not provide many development grants. In total, about 22% of Africa’s debt is to China. These loans are tied, which means they require that the projects be implemented by Chinese contractors. On the one hand, this increases efficiency. Compared to lenders like the World Bank, Chinese projects are relatively speedy. A recent project in Ghana took only 18 months from the start of negotiations to the start of construction.

A Kenya Railways Corp. freight train pulls shipping containers as it departs from the port station on the Mombasa-Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) line in Mombasa, Kenya, on Sept. 1, 2018. China’s modern-day adaptation of the Silk Road, known as the Belt and Road Initiative, aims to revive and extend trading routes connecting China with Central Asia, the Middle East, Africa and Europe via networks of upgraded or new railways, ports, pipelines, power grids and highways. (LUIS TATO/BLOOMBERG/GETTY IMAGES)

The downside is that the terms of Chinese loans are frequently extremely opaque, which makes it difficult for African courts and civil society to exercise oversight. The opacity also increases the danger of corruption, as seen in the case of the Kenyan SGR above. These issues are currently coming to a head as African governments are forced into renegotiating their Chinese loans due to the global economic impact of the Covid-19 pandemic. China has joined the G20’s Debt Service Suspension Initiative (aimed at providing poor countries a temporary freeze in debt servicing to allow them to deal with the health crisis.) However, in its debt renegotiations with African partners, Beijing has insisted on an opaque, case-by-case approach. This in turn has caused Africa’s commercial and Eurobond lenders to delay their own renegotiation processes, out of fear that Chinese lenders will get better terms. As a result, African countries face the danger of running out of time and slipping into defaults on their loans while also battling an unprecedented health crisis.

The longer-term implications of this debt are still unclear. Over the last few years, American officials have warned that China is setting so-called ‘debt traps’ for poor countries, by enticing poor countries to lend more than they can afford. Once the country slips into debt distress, Chinese actors will then seize collateralized state assets. The main case cited as proof of this narrative is the Hambantota port in Sri Lanka, where the renegotiation of debt led to a Chinese company signing an exclusive 99-year lease on the port and surrounding areas. However, research has debunked this claim, showing that the Hambantota case wasn’t a debt-for-equity swap. Rather, the deal was reached as a way for the Sri Lankan government to pay off other loans, and the Hambantota loans still have to be repaid. Up to now, there has been no evidence of Chinese actors seizing assets in Africa.

That said, it seems clear that Africa’s heavy Chinese debt burden will shape its development in the future. However, this is truer for a few large African economies than for the continent as a whole. For example, during the early 2000s, the China Development Bank extended a number of oil-backed loans to Angola, a form of financing that came to be known as the Angola Model. At that time, Angola was a major oil exporter to China. The loans, to be repaid in oil, was also agreed at a moment of high oil prices. Subsequently, Angola’s share of China’s oil sales shrunk due to competition from Saudi Arabia, Russia, and the U.S. At the same time, global oil prices fell, which forced Angola to pay back a lot more oil than it had anticipated. In 2020 it was reported that these volumes made it difficult to bring sufficient oil to market. Angola was recently forced to renegotiate its loans with the China Development Bank, in the face of 2020’s pandemic-related economic crisis.

While China doesn’t seem interested in seizing assets in Africa, the wider implication of its loans to the continent will likely be closer political alignment between China and African countries in multilateral institutions like the UN, and the general increase of Chinese political leverage in Africa.

Technology and consumer market development

Africa is not frequently thought of as a technology hotspot, but this is changing rapidly. Africa’s startup sector is growing rapidly, on the back of rapid expansion of ICT capacity in key countries. Chinese companies like Huawei, Transsion and ZTE are playing a key role in this trend. As with other forms of infrastructure, Chinese involvement in building ICT networks is aided by the close relationship between Chinese contractors and Chinese state banks like the China Exim Bank. The close relationship means that Chinese companies like Huawei are involved in almost every level of African ICT development. On the network side, Chinese contractors’ experience in challenging environments mean that they are the preferred partners to state bank-funded projects including submarine network provision and the construction of 4G and 5G networks in both rural and urban environments. It is estimated that Huawei has built 70% of Africa’s 4G capability.

However, the presence of these companies in Africa is more complex than their link with state banks. A company like Huawei has maintained a long presence in Africa. This includes building up close working relationships with African mobile service providers, like MTN in South Africa and Safaricom in Kenya. Huawei provides components, technical support and training to these companies. For this reason, African leaders have been loath to join pressure from the U.S. to stop working with these companies. Another reason for this hesitance is that these companies are also major sources of consumer electronics in Africa. The Chinese company Transsion is now the largest seller of mobile phones in Africa. Their products have been adapted to African conditions, and they sell both smartphones and old-fashioned feature phones, which frequently work better in areas with low network connectivity.

A staff member of Huawei introduces the latest technology of Huawei products to visitors from Benin at a forum of Northern Africa Innovation Day in Tunis, Tunisia, on Sept. 23, 2019. China’s Huawei launched a forum of Northern Africa Innovation Day co-organized with the Tunisian government on Monday in Tunis. The event was attended by more than 300 Arab and African officials and specialists. (ADELE EZZINE/XINHUA/ALAMY)

On the back of their provision of network and consumer hardware, Chinese companies are becoming more and more involved in the African tech services sector. African companies are world leaders in consumer financial technology (fintech) applications, notably in micropayment and microloan applications. Chinese venture capital investors now routinely take part in investment rounds in these sectors and joint ventures between Chinese and African tech companies are becoming more common. This is also true for media services. At the time of writing, the Chinese music streaming service Boomplay has about 65 million users in Africa (more than all the paying subscribers to Apple Music in the world.) The satellite TV company StarTimes has a similarly formidable footprint in both East and West Africa, one that is further boosted by its provision of content in African languages, and its 10,000 Villages Project, which rolls out satellite TV access to poor communities, again with the support of Chinese state banks.

Chinese technology provers are also increasingly promoting ‘Smart City’ and ‘Safe City’ projects in Africa. These frequently have a strong public safety and policing component, powered via Chinese facial recognition, AI and surveillance capabilities. African governments promote these as responses to the problem of urban crime. However, critics are concerned that these surveillance systems could also be turned against political opponents. Chinese companies have come in for a lot of criticism from Western governments for promoting this technology in Africa, especially to authoritarian governments. However, independent research has shown that Western companies are similarly willing to provide these tools to illiberal governments.

Development models

China’s engagement with Africa is strongly development-focused. This is driven by African authorities. For example, the African Union has put much emphasis on its own continent-wide development plan, known as Agenda 2063, and its Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa (PIDA). However, China’s own story of rapid development carries a lot of weight in Africa. While Chinese officials frequently downplay the direct applicability of Chinese modes of development in other countries, they also promote China as a uniquely equipped development partner thanks to its own dazzlingly rapid development arc.

In Changzhou City, Jiangsu Province, China, April 2, 2020, A worker is assembling locomotives that will be exported to Nigeria. These locomotives will serve Nigeria’s Akha railway and Rai railway, which are all built in Africa with Chinese technical standards. (COSTFOTO/BARCROFT MEDIA/GETTY IMAGES)

One of the models China promotes is infrastructure-boosted development via mass manufacturing. This doesn’t only focus on individual pieces of infrastructure, like ports. It is frequently presented in a bundled form, known as the ‘Port-Park-City’ model. This refers to development focused on specialized industrial parks (frequently known as Special Economic Zones) which attract manufacturing businesses through privileged access to cheap electricity and other perks. These are linked (frequently via rail) to the ‘City’ – a nearby settlement supporting workers and support industries, and to the ‘Port’, which facilitates mass exports – a key aspect of China’s development.

The Chinese-funded special economic zones of Ethiopia, linked via a rail line to the port of Djibouti, which is currently run by a Chinese company, is one of the clearest examples of this model in action. It is aimed at boosting development through low-wage manufacturing and exports. These initiatives are also frequently centrally planned by governments, rather than driven by the private sector – all hallmarks of Chinese development. Chinese investments in Ethiopian Special Economic Zones, focused on the shoe and apparel sector, helped it to establish itself as an exporter to the European market. Western brands like H&M have subsequently also started manufacturing in Ethiopia.

The Chinese model stands in contrast with Western ideas of development, which emphasize the rule of law, democracy, the building of transparent public institutions, and a strong private sector-led approach.

While the Chinese approach has been successful in Ethiopia, and several other special economic zones are being planned in other African countries, there are questions about whether they’re really suited to African conditions. The rising costs of labor in China has led many to argue that offshoring some of this manufacturing to Africa could create jobs. However, many Chinese manufacturing jobs migrated to poor provinces in western China, or countries like Vietnam and Bangladesh, or were lost to automation instead. African countries’ electricity supplies and support industries are frequently not well-developed enough to support the special economic zones. In addition, there are questions about whether Africa’s development trajectory will include a mass manufacturing phase or whether it will leapfrog directly into a service economy, as can be seen in the rapid rise of African fintech startups.

Despite these questions, it should be acknowledged that China’s record of development, and its provision of a new, non-Western development model, carry significant weight among African leaders. The history of deliberate under-development under Western colonialism is still holding Africa back today, and in that context, China is seen as a key alternative.

Future issues in the China-Africa relationship

U.S.-China tensions

The last few years have seen growing tensions between the U.S. and China, as seen in trends like the Trump administration’s pressure on Chinese companies and the ongoing trade tensions between the two countries. China’s lending to countries in the global south, and its Belt and Road Initiative have drawn sharp criticism from U.S. government officials. While the Trump administration has been particularly hawkish about China’s growing international presence, China’s rise raises concerns on both sides of the political aisle in the U.S.

China’s large role as a development partner in Africa puts the continent in a difficult position in relation to these growing tensions. There are fears that it will come under increased pressure to choose between its development partners, an outcome most African leaders are anxious to avoid.

Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta (C) attends the launching ceremony of the 50 MW solar power farm in Garissa, Kenya, Dec. 13, 2019. The plant, designed and built by the EPC contractor China Jiangxi Corporation for International Economic and Technical Co-operation (CJIC), in conjunction with Kenya’s Rural Energy Authority (REA), is one of the largest photovoltaic electricity stations in Africa. (XIE HAN XINHUA/EYEVINE/REDUX)

As mentioned above, China’s relationship with Africa is overwhelmingly structured through bilateral relationships. However, U.S.-China tensions are also increasingly playing out in multilateral arenas, like the United Nations. China’s cooperation with African states in these forums date back to the Cold War, when African votes helped the People’s Republic of China to displace Taiwan as China’s official representative at the United Nations. More recently, African votes have helped to secure positions for Chinese officials at the head of key UN agencies. African countries also helped defeat resolutions by Western countries criticizing Chinese human rights conduct in places like Xinjiang.

The reason for this cooperation is complex. It can be partly located in the fact that China is a massive trading, investment and development partner to these countries, and African leaders see cooperation on issues like Xinjiang as a relatively low-cost way to ensure the long-term continuation of the relationship. However, this conduct can’t only be ascribed to financial factors. It also has to do with African perceptions of being largely structurally excluded from forums like the UN Security Council, the G7 and G20, and the Bretton Woods Institutions. China routinely voices support for the reform of these institutions, and supports African candidates for their leadership. For this reason, the U.S.-China tensions also play out in institutions like the World Health Organization. Any attempt at resolving these tensions will also have to include greater focus on the systemic exclusion of African countries from these institutions, and on the U.S. building wider coalitions around shared values.

Energy

China is in the unusual position of being both the world’s largest implementer of coal-fired power capacity, the largest importer of foreign oil, and yet, also by far the world’s largest implementer of renewable energy capacity. All these factors will have significant impacts on Africa.

In the first place, Chinese state-owned enterprises are under much pressure to find overseas markets. The expertise in these companies tend to hew more in the direction of conventional energy (renewables are better represented in the private sector.) This means that these SOEs are actively campaigning for projects in markets like Africa. There is currently several conventional power plants being built by Chinese companies in various African countries, which lock these regions into decades of unsustainable electricity provision. At the same time, Chinese providers of renewable energy are also well-represented on the African continent. Several large-scale Chinese-funded and built solar installations have been finalized in African countries, and several more are in process.

While there is some evidence of a bias among Chinese state banks towards funding projects headed by SOEs, the choice between renewable and conventional power generation frequently lies with the African government. Chinese contractors have expertise in both sectors and Chinese banks fund both. In fact, the Chinese-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank recently announced that it will cease funding coal-powered electricity generation in the future.

This means that the choice between polluting or sustainable energy frequently comes down to how much pressure local communities and civil society organizations can put on African governments, and how much power local hydrocarbon lobbies wield. There is evidence of growing resistance against coal-powered electricity from African communities. In 2018, a group of NGOs representing local communities successfully sued the Kenyan government to stop a partially Chinese-funded coal-powered plant that was going to be built in near Lamu Island, a UNESCO World Heritage site. However, in other countries like South Africa and Zimbabwe, controversial Chinese-funded coal-powered projects are still going ahead. It remains to be seen whether it will be possible to convince Chinese authorities to stop funding coal capacity.

Activists march on June 5, 2018, in Nairobi carrying placards bearing messages to denounce plans by the Kenyan government to mine coal close to the pristine coastal archipelago of Lamu, on World Environment Day. (TONY KARUMBA/AFP/GETTY IMAGES)

The Belt and Road Initiative

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) can probably best be described as a set of policy directives issued by the Chinese government aimed at directing a myriad of Chinese actors towards a massive global rollout of infrastructure. In a larger sense, it can be seen as a vision of a China-centric world, with infrastructure connecting China to large parts of the global south and Europe. However, it also includes numerous even bigger initiatives, including a component focusing on space exploration, and another on health cooperation.

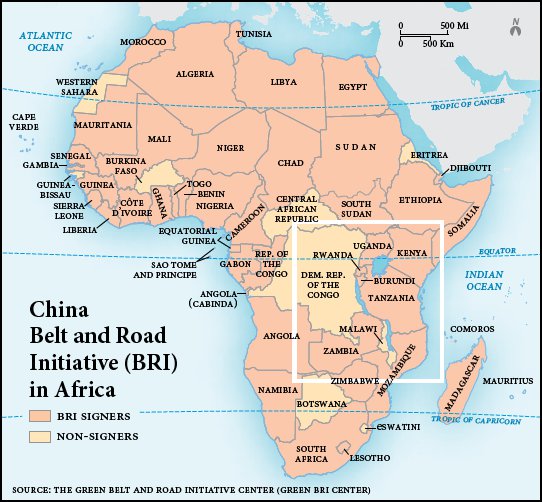

The BRI was announced by President Xi Jinping in 2013, and has subsequently become the centerpiece of Chinese foreign policy and international development strategies. The BRI is based on the so-called ‘five connectivities.’ This is shorthand for connections forged between member countries through infrastructure connectivity, free trade, financial integration, policy coordination and people-to-people exchange. Joining the BRI is open to all countries, by signing a Memorandum of Understanding with the Chinese government. As of March 2020, 138 countries have joined the initiative, including 44 African countries.

Many Chinese infrastructure projects in Africa preceded the announcement of the BRI, but they have been retroactively categorized as BRI projects. Since the coining, about 80 Chinese state-owned enterprises have launched about 3,100 BRI-related projects worldwide.

The long-term aim of the BRI is to strengthen economic and other links between China and other countries, especially those on the Indian Ocean rim, in Southeast, South and Central Asia, and in Europe, but also drawing in countries further afield. These links will aid the centrality of the Chinese economy in the world, and help to foster closer cooperation between China and partner countries in many spheres.

This push towards greater influence has drawn negative reactions from the U.S., as well as from Asian powers like India. At present, it is still unclear how much of the BRI will be built, especially in the face of a global recession due to Covid-19, and a longer-term slowing down of the Chinese economy. However, it is clear that the initiative enjoys strong political will from the Chinese Communist Party. The fact that President Xi Jinping has made it a centerpiece of his administration. The fact that the term limits on his reign were removed in 2018 makes it likely that the BRI will remain central to Chinese relations with the external world, including Africa, for the foreseeable future.

The U.S. has viewed the expansion of China’s engagement with Africa with some alarm. The Trump administration has put containing Chinese influence on the continent at the heart of its Africa policy. However, African leaders have so far resisted pressure to choose sides between the major powers. Calls to stop cooperating with companies like Huawei has proven particularly unsuccessful. China’s provision of finance, its experience in building infrastructure in challenging terrain, and efficiency in project delivery outlined in this chapter explain why many African countries are unwilling to sever their relationship with China.

Rather than confronting the China-Africa relationship head-on, U.S. policymakers would be better advised to focus on rebuilding the U.S.-Africa relationship, through focusing on areas of where the U.S. has particular advantage. These include:

1) Education: While China is pouring significant resources into educational exchange with Africa, the U.S.’s university system is unparalleled in strength. Africa has a very young population and education is one of its most pressing needs. Moves by the Trump administration to make it more difficult for African students to study at American universities are extremely unhelpful, and should be reversed immediately. Rather, American universities should lead African outreach efforts. The more Africans studying in the U.S., and the more American universities collaborate with African counterparts, the more America’s voice and worldview will gain influence on the continent.

2) Debt: Africa is currently suffering from unsustainable debt levels, which threaten to erase two decades of sustained economic growth. As was unpacked in this chapter, a major part of this debt is to China, and the opacity of Chinese lending practices has significantly contributed to the problem. The U.S. can do much to help its own financial sector to make it easier to provide relief of commercial debt to Africa. At the same time it would be very helpful if the U.S. spearheaded a global effort to get China to conform to global norms of transparency in lending.

3) Services: As outlined in this chapter, China has a particularly strong capacity for infrastructure provision. Few countries can compare with this ability, especially as regards project implementation in challenging terrains like one finds in Africa. Rather than facing China head-on in the sector, I would suggest that the U.S. focuses on its unparalleled strength in the service sector. Greater involvement from US legal firms, consultancies and research institutions would help a lot in making Chinese projects in African countries more sustainable, and to aid civil society organizations in getting African governments to make the terms of infrastructure contracts more transparent.

U.S. philanthropist and Microsoft founder Bill Gates speaks during the 32nd African Union (AU) summit in Addis Ababa on February 10, 2019.While multiple crises on the continent will be on the agenda of heads of state from the 55 member nations, the two-day summit will also focus on institutional reforms, and the establishment of a continent-wide free trade zone. (SIMON MAINA/AFP/GETTY IMAGES)

4) Media diplomacy and diaspora outreach: While China has made important inroads into the African mediasphere via companies like the satellite TV provider StarTimes, American media still enjoys massive popularity on the continent. This is especially true for African American TV, music and sports. This popularity provides many opportunities to use African American media as vehicles for public diplomacy. In addition, the U.S. has a massive advantage over China due to the large communities of African expatriates living in the U.S. African countries like Nigeria and Ghana have maintained fruitful cross-Atlantic networks with diaspora populations, while also spearheading outreach to the wider African American community. These programs are extremely valuable in providing the U.S. with a voice on the continent, especially in comparison with China’s frequently unhappy relationship with communities of African expatriates in cities like Guangzhou. However, the U.S.’s influence in Africa is gravely affected by well-founded perceptions that Black communities in the U.S. face discriminatory policing and other exclusionary measures. This tarnishes the image of the U.S. among particularly middle class and wealthy populations in Africa.

5) Technology: As outlined in this chapter, China is a major internet and mobile phone provider to Africa. The U.S. has attempted to pressure African countries to stop this cooperation, to little avail. It would be more fruitful to encourage greater cooperation between the U.S. and African tech sectors. There are numerous African startups looking for venture capital, and many chances for joint ventures. Closer working relationships between the African tech sector in countries like Nigeria, South Africa and Kenya, and Silicon Valley, will be beneficial to both sides, while also offering African countries choices beyond China. Keep in mind that many African actors share some U.S. misgivings about Chinese technology, but they don’t have many alternatives. Matchmaking between U.S. companies and African partners will have the effect of diversifying the African technology and startup sector, while expanding American access to the world’s last major emerging market for consumer technology.

discussion questions

1. How has Africa’s historical relationship with Europe shaped its relationship with China? How does the concept of South-South solidarity strengthen China’s position in Africa?

2. Why have U.S. efforts to stop African cooperation with China been largely unsuccessful? Are there ways to redefine the way the U.S. approaches the issue?

3. What are the hallmarks of the Chinese development model as it relates to Africa? Do you think it is a suitable option for Africa?

4. How do you think debt will reshape the China-Africa relationship? Which options are open to Africa to make its debt burden more sustainable without giving up on its development goals?

5. What are the pros and cons of Africa collaborating with Chinese technology companies? Do you foresee other tech companies acting as competitors, and why?

6. Which role has infrastructure played in the China-Africa relationship? How do you think this affects African development?

suggested readings

Alden, Chris and Large, Daniel, New Directions in Africa - China Studies, 368pg: Routledge, 2019. A wide-ranging collection of writing from some of the most prominent scholars in the field on a wide range of Africa-China issues. A good introduction to the breadth of the relationship.

Shinn, David and Eisenman, Joshua, China and Africa: A Century of Engagement, 542pg. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012. A comprehensive introduction to the history of China-Africa relations, providing detailed country views.

Brautigam, Deborah, Will Africa Feed China? 247pg. Oxford University Press, 2015, This book takes a close look at the issue of agriculture exports from Africa to China, and fact - checks allegations of Chinese land grabs in Africa. A valuable corrective to misinformation about Chinese activities in Africa

Benabdallah, Lina, Shaping the future of power: Knowledge Production and Network-Building in China-Africa relations, 204 pg. University of Michigan Press, 2020. This book focuses on the role of training and skills transfer in forging China - Africa relationships. A very valuable account of both civilian and military engagement

Gagliardone, Iginio, China, Africa and the future of the Internet: New media, new politics, 202 pg. UK: Zed Books, This book provides a detailed account of Chinese internet provision in Africa, and challenges some common perceptions of Chinese companies’ impact on democracy in Africa.

Sun, Irene Yuan, The next factory of the world: How Chinese investment is reshaping Africa, 224 pg. Harvard Business Review Press, An accessible account informed by field research of the impact of Chinese industrialization efforts notably in Ethiopia.

Don’t forget: Ballots start on page 104!!!!

To access web links to these readings, as well as links to global discussion questions, shorter readings and suggested web sites,

GO TO www.fpa.org/great_decisions

and click on the topic under Resources, on the right-hand side of the page.