by Scott A. Snyder

SCOTT A. SNYDER is senior fellow for Korea studies and director of the program on U.S.-Korea policy at the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR). His program examines South Korea’s efforts to contribute on the international stage; its potential influence and contributions as a middle power in East Asia; and the peninsular, regional, and global implications of North Korean instability.

! Before you read, download the companion Glossary that includes definitions, a guide to acronyms and abbreviations used in the article, and other material. Go to www.fpa.org/great_decisions and select a topic in the Resources section. (Top right)

North Korea’s leader Kim Jong Un (R) walk with South Korean President Moon Jae-in (L) during a visit to Samjiyon guesthouse in Samjiyon on September 20, 2018 in Samjiyon, North Korea. Kim and Moon meet for the Inter-Korean summit talks after the 1945 division of the peninsula, where they will discuss ways to denuclearize the Korean Peninsula. (PYEONGYANG PRESS CORPS/POOL/GETTY IMAGES)

Since the Korean War, South Korea has emerged as an economic powerhouse with growing global capabilities and influence, a knack for scientific and technological innovation, and a rapidly expanding set of cultural offerings that have captivated audiences around the world. South Korea has become a critical ally to the U.S. in Northeast Asia and serves as an example of how nations can leverage their middle power status to have an outsized impact on the global agenda. The overwhelmingly positive global assessment of South Korea’s handling of the Covid-19 pandemic and cultural power of K-Pop serve as two examples of this phenomena. However, domestic economic and political woes, intensified Sino-U.S. rivalry, the continued North Korean nuclear threat, and increasing pressures on the U.S.-South Korea alliance relationship threaten to derail South Korea’s aspirations for autonomy and its ability to secure its national security interests on its own. As Northeast Asia enters an era of great power conflict, South Korea may be forced to make choices between the U.S. and China that it has thus far avoided, and these choices will likely have lasting implications for the Korean Peninsula.

South Korea’s Candlelight Movement President

South Korea’s President Moon Jae-in is the standard bearer of the “candlelight movement,” an outpouring of South Korean public demands for accountability in the wake of the allegations of corruption, extortion, and self-dealing against former President Park Geun-hye that led to her impeachment in fall 2016. Those allegations came to light when the Korean media found a lost laptop of Park’s close friend and associate Choi Sun-sil containing incriminating evidence regarding Choi’s efforts to use her close relationship with President Park to secure funds from the Samsung Corporation and other leading conglomerates for her daughter’s equestrian career and terests, first as a democratization movement leader and human rights lawyer in the 1980s, later as a top aide and chief of staff to progressive South Korean president and fellow human rights lawyer Roh Moo-hyun in 2003–08, and finally as the leader called to restore South Korean public faith in leadership and to bring about a less corrupt, more accountable government.

The circumstances under which Moon took office following Park’s impeachment created an immediate need for inclusive and restorative leadership. Moon needed to restore the South Korean public’s confidence in their president. Moon’s comments at his inauguration the day after his election set the to secure a place for her daughter at the prestigious Ewha Womans University. These revelations mobilized the largest peaceful public protests since Korea’s democratization in the late 1980s, with Moon and other progressive leaders at the forefront, tanking Park’s public approval ratings to four percent.

Supporters of South Korea’s former president Park Geun-hye gather during a rally demanding the release of Park Geun-hye outside the Seoul Central District Court in Seoul on April 6, 2018. (JUNG YEON-JE/AFP/GETTY IMAGES)

The massive withdrawal of public support led to Park’s impeachment in December 2016 and removal from office in March 2017, followed by a constitutionally-mandated snap election held within 60 days of the Constitutional Court’s impeachment ruling. Moon won with 41 percent of the vote over a fellow reformist, Ahn Cheol-soo, and a conservative rival, Hong Joon-pyo. For Moon, who had narrowly lost to Park five years earlier, the victory was vindication for a career spent promoting government accountability to public in-right tone: “I will become an honest president who keeps his promises … Genuine political progress will be possible only when the president takes the initiative in engaging in politics that can garner trust. I will not talk big about doing something impossible. I will admit to the wrong I did. I will not cover up unfavorable public opinion with lies. I will be a fair president.” Moon pledged both to restore public trust and set high expectations for his administration’s performance.

In addition, Moon made striking efforts to emphasize that he was accessible and in tune with public sentiment, in contrast to the image of his cloistered and imperious predecessor. Moon had tea on the Blue House lawn with his new staff, visited Korean shop owners and factories, and fashioned an Obama-like image of accessibility and inclusion in his public appearances. Moon also established a national petition platform on the Blue House website that enabled the public to directly petition the Blue House and committed the government to respond if the public petition garnered support from 200,000 citizens within 30 days.

A second immediate challenge was the task of selecting a team of officials to build and implement Moon’s policy platform without the benefit of time for a transition. In the initial weeks of his presidency, Moon was surrounded by hold-over appointees from a caretaker government largely appointed by Park. Having already assumed the office of the presidency, Moon had to appoint his own personal staff and select new cabinet ministers to lead the bureaucracy. Moon’s first hundred days were more about gaining control over the levers of government than about implementing policy measures prepared in advance of his assumption of office.

Beyond those challenges, Moon inherited a daunting set of economic problems. South Korea’s economy was beset with relatively low growth rates compared to prior historical performance benchmarks, overdependence on export-led growth primarily generated by Korea’s largest conglomerates at the expense of domestic growth, and exceptionally high youth unemployment combined with an inadequate social safety net to support South Korea’s aging population.

Moon’s initial economic policies focused on expansion of public sector hiring, boosting of South Korea’s minimum wage, encouragement to businesses to transition workers from contract to regular work status with full benefits, and imposition of a ceiling on work hours per week. But this wage-led economic growth policy proved controversial and ineffective, especially for the small businesses that bore the brunt of mandatory wage increases and work-week limits. Under the burden of the costs imposed by new regulations, many small businesses shed workers and faced greater difficulties staying afloat.

Another of Moon’s controversial policy involved real estate reforms designed to curb speculative investments, including the imposition of higher taxes on owners of more than one property, capping of rent increases, and the revamping of South Korea’s traditional one hundred percent down payment rental system. The real estate taxes targeted rich South Korean landholders with multiple properties, but their impact was made more complex by the illiquidity of housing investments and the fact that Korean families have traditionally seen housing as a safer avenue for investment than the Korean stock market. The desired impact of the real estate tax reforms was to drive prices down, lowering the price of entry into the housing market for younger buyers, but instead resulted in higher prices, greater illiquidity in the real estate market, and significant public backlash.

Moon proved more successful in directing long-term government investment into areas designed to enhance provision of public goods while also stimulating economic growth. The investments mainly targeted the Digital Economy and Korea’s own Green New Deal, which both involve substantial outlays of public capital but also promise to generate hundreds of thousands of jobs in sectors that would make the Korean economy more efficient long-term.

Perhaps the most contentious of Moon’s policy initiatives proved to be in the area of public sector reforms, most notably reforms of the institutional structure of the public prosecutor’s office and anti-corruption agencies that generated resistance among prosecutors and public backlash. Moon’s reforms touched on ingrained power-holding institutions such as the public prosecutors’ office but came to be perceived among Moon critics as revenge rather than reform; i.e., designed to perpetuate progressive political power and to institutionalize a base for perpetuation of long-term political influence at the expense of conservative opposition.

Most controversial was the proposal to establish a prosecutorial office dedicated to investigation of political corruption, but without sufficient transparency as to whether the new office would truly operate independently of executive branch influence. Skeptic doubts about the new institution were inflamed by an ongoing public spat between the justice minister and the chief prosecutor over control of prosecutorial appointments within the existing apparatus. Debate continues over whether the reforms are intended to improve the system or to tilt the playing field to the benefit of the party in power.

Moon’s greatest political asset as president has been the perception that he has historically operated as a “clean” leader who has avoided the political corruption scandals that have stained so many high-level Korean political leaders. On balance, Moon’s steady hand, basic competency, and moderation has been rewarded with relatively high public support ratings. But Moon’s caution and prudence have also resulted in political weakness to the extent that he has either been perceived as indecisive or as susceptible to manipulation by more ideologically-driven advisers.

Covid-19 and the Korean response

The world watched as the Chinese city of Wuhan reeled from the effects of a new strain of coronavirus in late January that led to a near total lockdown of the city. For South Korea, the U.S., and the rest of the world, the virus seemed a world away and the initial focus was on extricating foreign nationals from the lockdown precipitated by the contagious nature of the virus officially named Covid-19 by the World Health Organization.

South Korea and the U.S. both recorded their first cases on January 30, 2020. Within days, South Korea became the first epicenter for spread of the virus outside of China. The Korean Center for Disease Control (KCDC) nimbly applied lessons learned from the spread of previous Asian coronaviruses such as the Sudden Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in the mid-2000s and the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) in 2014 to contain the first wave of the virus within weeks, providing a textbook example of effective contagious disease response as other countries struggled to respond.

The most important initial step in South Korea’s response was the mobilization of effective public-private cooperation to produce a test for Covid-19 detection based on information about the genetic structure of the virus provided by China. This public-private coordination enabled South Korea to build out and ramp up an effective testing regime. Within days, South Korean companies were producing tests and labs were analyzing the results to diagnose Covid-19 cases. South Korea introduced drive-through testing, a technique quickly adopted around the world that made testing widely available and reduced contamination risks that would accompany patients into doctor’s offices and hospital waiting rooms.

The second element of South Korea’s response learned from prior experience with SARS and MERS involved the mobilization of cell phone technology to conduct contact tracing. By marrying cell phone tracking with information about the movements of those who had contracted Covid-19, the KCDC effectively traced the spread of the disease and provided text message warnings to those who had come into contact with identified Covid-19 carriers and to those visiting places that had also been visited by Covid-positive patients.

This technology-driven approach has inspired debate about balancing public health concerns and individual privacy, both through the tracing of the proximity of individuals to locations where spread occurred and through the use of information about individual whereabouts without user consent. The risks of state intrusion on individual privacy were thrown into relief by widespread reporting on Covid-19 spread. The first clash came in government use of technology to identify patrons of same sex and transgender bars where patrons sought anonymity because of the risks of social stigmatization. A second clash came through the government’s use of technology to identify patrons of churches that had become conservative catalysts of political opposition to the Moon administration.

The third element of South Korea’s successful initial Covid-19 response involved treatment practices, including effective triage of severe cases that reduced the burden on hospital caseloads and provision of quarantine facilities where doctors and nurses could monitor patients while reducing the risk of further spread. South Korea’s quarantine protocols and offers of testing for undocumented migrants in Korea without fear of deportation also included quarantine requirements and provision of room and board for foreigners to prevent travelers from introducing the disease from outside South Korea.

South Korea’s response to Covid-19 benefited from high South Korean trust in specialized expertise within South Korean government institutions. KCDC Director Jeung Eun-kyung and her colleagues led South Korea’s response with twice daily briefings that emphasized the importance of a public health response to the virus and provided the South Korean public with clear guidelines on how to respond.

South Korea also benefited from the fact that the habit of mask-wearing was already a part of the culture, as a means to prevent spread of illnesses, to show courtesy to others, and due to worsening air quality in South Korea. The benefits and utility of mask-wearing were already widely accepted in South Korea, and further strengthened by guidance from the KCDC emphasizing the importance of personal protective equipment (PPE), social distancing, and hand cleaning.

Thanks to its mobilization of public-private cooperation, technology-driven approach, effective treatment practices, culture of mask-wearing, and the relatively high compliance of the South Korean public with government instructions, South Korea avoided a China-style lockdown in its initial response. South Korean day-to-day activities in many areas were subdued, but not suppressed, by state guidelines. Many restaurants remained open, though economic activity was hindered by Korean personal choices to avoid dining choices that might heighten the risk of community spread.

South Korea quickly dropped from the country with the second largest number of detected cases at the beginning of March to ranking seventy-fifth in number of cases at almost 20,000 by the end of August. South Korea experienced around three hundred Covid-19 deaths from January to August out of a population of fifty million people, or a rate of six deaths per million people. South Korea recorded the 150th highest mortality rate per capita among over 200 countries and territories during this time period. South Korea’s successful initial response has become a talking point for the Moon administration at international meetings, and South Korea’s supply of Covid-19 test kits and PPE has become a diplomatic opportunity for it to enhance its positive image and engender international good will.

In contrast, North Korea’s response to the pandemic remains shrouded in secrecy and characterized by disinformation. North Korea’s isolation means that the international community knows little about the true impact of Covid-19 on the North Korean people. The North Korean state media emphasized public awareness of the virus early on and imposed a strict quarantine on import of goods as well as restrictions on foreign diplomats in Pyongyang, enhancing state control over both information and goods from the outside and reducing the possibility of Covid-19 spread.

While publicly denying any Covid-19 cases since the outbreak began to receive public notice in January 2020, North Korea has quietly requested Covid-19 test kits and PPE from international organizations as well as friendly states such as China and Russia and rejected offers of assistance from South Korea and the U.S.. Both the level of state media attention to Covid-19 and periodic reports from defector-based media suggest that Covid-19 deaths have occurred inside North Korea, but it is impossible to know how widespread the virus might be or to believe that North Korea would not succeed in utilizing draconian methods to quash the virus once detected. Ultimately, Covid-19’s impact on North Korea will likely stem not from the spread of the virus itself, but from the enhanced state measures undertaken to quarantine imports and to contain the spread of the virus.

The revival and decline of inter-Korean summitry

Civilians from Hungnam in North Korea boarding the landing ship ‘USS Jefferson County’ (LST-845) of the US Navy, as they flee their city during the Korean War, 19th December 1950. The evacuation of Hungnam was code-named Christmas Cargo. A US Navy Defense Department photograph. (US NAVY DEFENSE DEPARTMENT/FPG/ARCHIVE PHOTOS/GETTY IMAGES)

South Korean President Moon Jae-in’s most heartfelt policy priority has been to serve as a peacemaker with North Korea. Perhaps, because his family originated in North Korea but fled south as part of the U.S.-led Hungnam evacuation in December 1950, Moon felt destined to reunite the two Koreas. Moon sought to restore a progressive policy of inter-Korean engagement and summit dialogue following in the footsteps of his predecessors Kim Dae-jung (1998–2003) and Roh Moo-hyun (2003–08). During that time, engagement with North Korea was premised on the idea that functional cooperation through promotion of a joint industrial complex at Kaesong and a tourism project at Mount Kumgang would lead to inter-Korean economic integration, to change inside North Korea, and eventually, to the long-held dream of Korean unification.

But conservative South Korean leaders reversed and dismantled these inter-Korean cooperation projects in response to six North Korean nuclear tests between 2006 and 2017 and the passage of over ten UN Security Council sanctions resolutions condemning those tests. The U.S. and North Korea were on a trajectory toward confrontation over North Korea’s nuclear and missile development. Moon sought to reverse the deterioration in relations with North Korea, but to do so, he would have to overcome North Korea’s animosity and reverse its nuclear development.

In this handout image provided by South Korean Defense Ministry, A North Korean soldier (L) shakes hands with a South Korean soldier during a mutual on-site verification of the withdrawal of guard posts along the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) on December 12, 2018 in DMZ, North Korea. (SOUTH KOREAN DEFENSE MINISTRY/GETTY IMAGES)

In July 2017, Moon began his quest with a policy speech in Berlin, the same city where Kim Dae-jung laid out his approach to inter-Korean relations in 2000. Moon emphasized the need for a permanent peace regime on the Korean Peninsula while calling on North Korea to accept “complete, irreversible, verifiable denuclearization” as an essential condition for achieving this peace. Moon sought to institutionalize a permanent peace structure on the peninsula and to draw a “new economic map on the Korean peninsula” by reconnecting railways and promoting nonpolitical exchange and cooperation.

Moon’s speech appeared to fall on deaf ears in Pyongyang as North Korea continued a break-neck pace of long-range missile testing and conducted its largest nuclear test to date in September 2017. But following a November 2017 test of its largest missile yet, the North Koreans announced that their long-range testing was complete. Kim Jong-un pivoted toward a diplomatic charm offensive, first sending an athletic team and a high-level delegation led by his sister, Kim Yo-jong, to the 2018 Pyeongchang Olympics in South Korea. Using inter-Korean Olympic engagement as a backdrop, Kim Jong-un pledged to “work toward complete denuclearization” in a series of three summit meetings with Moon Jae-in in April, May, and September 2018.

The April 27, 2018, Panmunjom Summit, held on the South Korean side of the demilitarized zone (DMZ) dividing the two Koreas, involved a full day of negotiations, private one-on-one meetings, and photo opportunities, which culminated in the announcement of the Panmunjom Declaration. The declaration included a road map for and pledges to institutionalize inter-Korean exchanges and dialogue in a wide range of areas, reduce military tensions, and establish a permanent peace regime on a denuclearized Korean Peninsula. The Panmunjom Declaration reaffirmed and built on the commitments made in prior inter-Korean declarations, serving as a catalyst for inter-Korean exchanges and for the construction and establishment of an inter-Korean liaison office at Kaesong.

A second impromptu, then-secret inter-Korean summit between Moon and Kim occurred a month later on the North Korean side of the DMZ in a successful effort to put back on track preparations for the first U.S.-North Korea summit meeting between Donald J. Trump and Kim Jong-un to be held in Singapore on June 12, 2018. Moon played a critical intermediary role in setting up the historic Singapore Summit on the basis of the explicit recognition that inter-Korean relations and U.S.-North Korea relations must move together to achieve lasting progress toward peace-and-denuclearization on the Korean Peninsula.

By the third inter-Korean summit on September 18–20, 2018, there appeared to be real momentum for a transformation of the situation on the Korean Peninsula. The Agreement on the Implementation of the Historic Panmunjeom Declaration in the Military Domain, known as the Comprehensive Military Agreement, removed guard posts from the DMZ and guns from the Joint Security Area and committed the two Koreas to joint remains recovery efforts inside the DMZ. The Pyongyang Declaration pledged the resumption of economic cooperation, cultural and sports exchanges, humanitarian exchanges for families divided by the Korean War, and the dismantlement of North Korean missile and nuclear facilities at Dongchang-ri and Yongbyon. These measures never got off the ground, and an anticipated visit by Kim Jong-un for a fourth summit in South Korea never materialized.

The summit pledges all rested on the assumption that the partial scope of North Korean nuclear dismantlement would satisfy the Trump administration sufficiently to secure UN Security Council sanctions relief or exceptions for inter-Korean economic projects. However, the “small deal” that the Moon administration hoped for and expected as the main outcome of the second Trump-Kim summit in Hanoi never materialized. The “small deal” failed in part because the North Koreans never engaged directly with American counterparts at the working level to negotiate specifics of denuclearization and in part because Trump determined that North Korean offers were insufficient to ensure that they would ever lead to the goal of “complete denuclearization.”

The Hanoi Summit failure undermined prospects for inter-Korean progress and appeared to sour the personal relationship between Moon and Kim. North Korea issued scathing criticisms of South Korea for failing to act independently of the U.S. on issues like inter-Korean cooperation and for failing to turn on the economic spigot of aid to North Korea that had flowed so generously in the early 2000s, prior to North Korea’s nuclear tests. Moon went from crucial intermediary to marginalized extra, not even getting a seat in the room at a third Trump-Kim meeting on June 30, 2019, at Panmunjom, which accomplished little more than a photo op and false hopes for renewed denuclearization talks between the U.S. and North Korea.

Kim Jong-un’s sister Kim Yo-jung publicly targeted Moon’s failure to stop North Korean refugees from sending leaflets by balloon into North Korea, shut down almost all inter-Korean communications, and ordered the demolition of the inter-Korean liaison office at Kaesong. Although Moon continued to hold the door open for peace talks with Kim Jong-un in 2020, Kim appeared to have moved on. Kim has doubled down on nuclear deterrence, self-reliance, and isolation as a safer and more secure option than the risks of an inter-Korean engagement unaccompanied by economic subsidies and nuclear blackmail on a scale necessary to keep nuclear North Korea afloat.

When Kim Jong-un took over as North Korea’s supreme leader following the death of his father, Kim Jong-il, in December 2011, questions swirled about whether his father’s associates, who were 40 years his senior, would accept or subvert Kim’s rule. A decade later, Kim Jong-un is the longest-serving leader in Northeast Asia. He has consolidated power by removing all potential rivals within or outside of his family – either through dismissal and demotion of military leaders or via the brutal execution of his uncle Jang Song-taek and assassination of his half-brother, Kim Jong-nam. Kim has charted a military and economic course that is making North Korea both stronger and more dangerous.

Kim Jong-un has indisputably been a more capable leader than his father Kim Jong-il both in terms of presenting a charismatic public image and in pursuing more effective economic policies. But he presides over a brutal system that demands unquestioning political loyalty from its people. Expressions of political loyalty to Kim are indoctrinated from cradle to grave through North Korea’s educational system and state media, and are an unconditional prerequisite to opportunities for limited personal and economic advancement within North Korea’s ideologically-based social hierarchy. Conversely, expressions of political disloyalty or defections within one’s immediate family make individuals vulnerable to confiscatory bribes and punishments by North Korean security services, banishment from Pyongyang, and an effective death sentence through assignment to political gulags in the countryside.

In contrast to his father, who eschewed public speaking, ruled via the nine-person National Defense Commission, and marginalized the party and government institutions, Kim Jong-un has normalized regular party functions, presided directly over party meetings, and given regular public addresses charting the country’s challenges, needs, and successes. Though he still occupies a god-like status within North Korea, Kim Jong-un has adopted a more open and direct style rather than ruling behind the curtain.

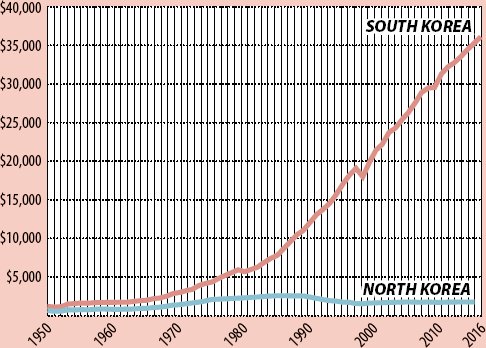

NORTH AND SOUTH KOREA GDP COMPARED, 1950 – 2016 (PER CAPITA IN U.S. DOLLARS)

SOURCE: THE MADDISON PROJECT

In 2013 Kim Jong-un announced his first major policy initiative, known as byungjin, or simultaneous economic and military development, which was intended to transform North Korea into a “strong and prosperous state.” On the economic front, Kim Jong-un expressed in one of his earliest public speeches the desire to lead an economy in which North Koreans would not have to “tighten their belts,” an oblique reference to the famine and privation the country faced under his father in the late 1990s. Kim authorized a loosening of North Korea’s command economy, partial privatization of agriculture, and the establishment of 15 special economic zones around North Korea. These policies and relatively good weather helped stabilize agricultural production and generated modest domestic economic growth through 2017, but the North Korean economy began to stumble in 2018 due to increasingly strict UN Security Council sanctions in response to North Korea’s nuclear and missile tests. By 2019, Kim Jong-un was urging self-reliance, tightening control over the economy, and warning that North Koreans may have to tighten their belts again to achieve a “frontal breakthrough” against hostile global forces.

Behind K-Pop’s Global Reach

For the world, 2020 has been a year marked by calamity, but South Korea’s cultural offerings have provided a silver lining to global viewers. Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite became one of the highest grossing film in South Korean cinema history and the first foreign movie ever to win best picture at the Oscars. In another first, Korean boy band BTS (Bangtan Sonyeondan, or Bangtan Boys) hit number one on Billboard’s top 100 with its song “Dynamite,” leading the pack of Korean artists who have begun to gain popularity internationally. The Korean drama Crash Landing On You also debuted as the third-highest rated show in South Korean cable television history, became massively popular in China, Japan, and Southeast Asia, and quickly climbed the list of most-viewed shows on American Netflix. What has accounted for the global popularity of Korean movies, music, and dramas in 2020?

The South Korean entertainment industry has spent over two decades building a global brand. Early on, Korean dramas gained traction regionally, with viewers in Japan, China, and Southeast Asia. The international recognition of Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite with an unprecedented 2020 Oscar win for Best Picture, along with Best Director, Best Original Screenplay, and Best International Feature Film, represents the culmination of decades of gradually increasing international acclaim for Korean cinema. Critics praised the film’s theme of class conflict, a South Korean story with global application in an era of widening social and class inequality.

South Korean directors such as Bong, Park Chan-wook, and Lee Chang-dong have built solid careers over decades and have earned international recognition from their peers for films such as Joint Security Area, Peppermint Candy, The Host, Burning, and Oldboy. Bong and Park have both directed English language films, including Okja, Snowpiercer, and Stoker, that have received positive reviews and acclaim from Western critics and audiences. Most significantly for the Korean film and drama industries, popular streaming platforms Netflix, Hulu, and Amazon Prime Video have made a wide array of titles available, ensuring that Korean cultural influence becomes even more popular and deeply-rooted in the American consciousness going forward.

Beyond the big screen, Winter Sonata was a breakout love story that experienced massive success with Japanese viewers in the mid-2000s. Winter Sonata and other Korean dramas including Jewel in the Palace, Boys Before Flowers, and Secret Garden made inroads across Asia, Europe, and even countries such as Iran.

Korean dramas keep viewers hooked with whiplash-inducing plot twists and deliver strong production values and excellent presentation. Most importantly, they focus on dramatic thematic elements such as the clash of family identity with social expectations in Korean society, the clash of modernity and urbanization with traditional cultural values, and themes such as class divides, income inequality, and social injustice that have struck a chord with overseas audiences and translated into international success. Most recently, highly-rated dramas such as Crash Landing On You, Kingdom, and Guardian: The Lonely and Great God have experienced great success in the West, likely thanks in part to their availability on Netflix.

But the “Korean wave” of cultural products has not been confined to screens, large or small. Korean pop music acts such as BoA, Rain, Wonder Girls, Super Junior, Big Bang, 2NE1, and Girls’ Generation gained popularity in the 2000s across Japan, China, and Southeast Asia. These groups brought a uniquely Korean style to their music, along with catchy beats and impeccably synchronized and choreographed dancing. These elements drew ever-wider audiences to the fanbases that flourished both across Asia and globally. But Korean pop music, or K-pop, did not catch the attention of most Americans until PSY’s 2013 breakout hit “Gangnam Style” set YouTube records with over one billion views and a “pony dance” built on a satirical view of the cultural hypocrisy and excesses of Seoul’s most wealthy district.

South Korea’s BTS has become the most successful group in the history of K-pop both domestically and overseas. BTS is the first Korean group to hit number one on Billboard’s Top 100 with its single “Dynamite,” which topped the charts the first week following its release in August 2020. BTS’ success has brought into the limelight the unique fanbases that bolster the popularity and success of K-pop bands and have used their power to circumvent the role of distributors within the music industry. The “BTS ARMY” fanbase has driven the viewership of BTS music videos on YouTube, elevated BTS-related terms to trending on social media, and organized campaigns that lead to BTS concert tickets selling out within seconds. When touring became impossible due to Covid-19, BTS held the world’s largest virtual concert with a paying audience of 756,000 concurrent viewers in 107 countries and territories.

NEW YORK, NEW YORK - DECEMBER 31: BTS performs during the Times Square New Year’s Eve 2020 Celebration on December 31, 2019 in New York City. (MANNY CARABEL/FILMMAGIC/GETTY IMAGES)

South Korean music labels have successfully recruited and trained Asian voices from across the world through a rigorous (and to some critics, abusive) regimen to meet high production values and develop their images as “idols” for a global audience. Blackpink, whose four members include vocalists from South Korea, New Zealand, and Thailand, has also made the Billboard Top 100 and is the first Korean girl group to produce two music videos with over a billion views on YouTube. Youth interest in K-pop has catalyzed a wave of Korean language learning among global fans, but top K-pop acts have also increasingly incorporated English lyrics into their songs and begun to partner with international stars, such as Blackpink’s recent collaborations with Lady Gaga, Cardi B, and Selena Gomez, to produce English songs.

The secret to the global appeal of Korean movies, dramas, and music has been their ability to show and tell unique aspects of a Korean story in ways that have global appeal, while also translating and redesigning popular elements of global culture by adding uniquely Korean characteristics. This combination of an openness to absorption of global culture and the ability to tap into universal themes of the Korean experience has enabled Korean artists to ride the Korean cultural wave to new heights of global popularity in 2020.

Kim has doubled down on North Korea’s nuclear and missile development, crediting these programs as part of the legacy of his father and grandfather and inscribing North Korea’s nuclear status in the preamble of a revised constitution. Kim conducted four nuclear tests of increasing size and yield between 2013 and 2017. Simultaneously, he presided over a sprint to develop survivable missile strike capabilities that could reach the U.S., by securing mobile launch capabilities, and by developing solid fuel versions of missiles that required shorter preparation times prior to launch. By November 2017, North Korea successfully tested the Hwasong-15 missile that, according to then Defense Secretary James Mattis, could reach any point on the globe. Kim declared his effort to build a nuclear deterrent successful and pivoted to a diplomatic charm offensive in early 2018.

Kim Jong-un framed his 2018 diplomatic outreach to South Korea, China, and the U.S. as possible thanks to his missile development success, but many external observers interpreted Kim’s willingness to come to talks as a sign of weakness and as evidence that Kim feared Trump’s 2017 proclamations of “fire and fury” and was feeling the effects of U.S. “maximum pressure” sanctions. Although Kim paid lip-service to the objective of “complete denuclearization,” at summits with Moon in Panmunjom and with Trump in Singapore, Kim’s primary objective appears to have been to legitimize North Korea as a nuclear state and to secure relief from the UN sanctions standing in the way of North Korea’s economic development goals.

The February 2019 Hanoi summit between Trump and Kim marked the failure of Kim’s bid for sanctions relief and shaped a reversion in North Korean policy by the beginning of 2020 to a focus on economic self-strengthening and reliance on nuclear deterrence. The 2020 triple whammy of continued economic sanctions, self-imposed quarantine in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, and extensive flooding from monsoons and typhoons comprise the most severe challenges North Korea has faced under Kim Jong-un’s rule.

Kim’s reportedly poor personal health and periodic extended absences from the public eye have raised questions about the future succession prospects for the Kim family regime in the absence of offspring old enough to take charge. The rise of Kim’s sister, Kim Yo-jong, to ever more powerful positions within the Korean Worker’s Party has fueled speculation about her future role. Kim’s gambit of achieving the twin goals of nuclear-backed security and market-reform driven prosperity to foster a strong and prosperous North Korea appear to have reached a dead end, with no face-saving way of reversing course.

New challenges for the U.S.-South Korea alliance under unorthodox political leadership

At first glance, it would appear that U.S. President Donald J. Trump and South Korean President Moon Jae-in have little in common, yet the U.S.-South Korea security alliance has both created incentives for them to work together while also constraining their ability to pursue independent paths. The two leaders have steered in different directions despite the strong bureaucratic institutional alignments that keep the alliance robust, but they have also found a distinctly political basis upon which to pursue a narrow window of cooperation based on common interest in a relationship with North Korean leader Kim Jong-un.

Trump is brash and direct. Moon is cautious but firm. Though the two have not embarked golf diplomacy like Trump and Japan’s Shinzo Abe, they have met relatively often, with little of the drama that has accompanied Trump’s meetings with other U.S. allies such as Germany’s Angela Merkel or Canada’s Justin Trudeau.

North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, U.S. President Donald Trump, and South Korean President Moon Jae-in inside the demilitarized zone (DMZ) separating South and North Korea on June 30, 2019, in Panmunjom, South Korea. (HANDOUT PHOTO BY DONG-A ILBO/GETTY IMAGES)

The most striking convergent political interest between Trump and Moon has been their shared focus on summit diplomacy with Kim. Without Moon’s facilitation and intermediary role, the conditions for the Trump-Kim summit in Singapore in June 2018 would have never materialized. A last-ditch secret inter-Korean summit at Panmunjom certainly kept it from going off the rails.

Moon has sought primarily to ensure peace on the Korean Peninsula through diplomacy toward North Korea. He perceives U.S.-North Korean reconciliation—and a resulting peace-and-denuclearization process that facilitates North Korea’s transition into the international community – as an important step toward that goal. Moon asserts that South Korea should drive such a denuclearization-embedded peace process. This policy overlaps substantially with the U.S. preferred peace-embedded denuclearization approach, but places peace as the primary goal rather than denuclearization. This approach also appealed to Trump’s sense of drama and history: if only Trump’s personal relationship with Kim could be leveraged to mobilize tangible steps toward a permanent peace treaty to replace the Korean Armistice Agreement, catalyze tangible North Korean steps toward denuclearization, and put Trump’s name in the history books as the author of a peace with North Korea.

Unfortunately, Moon’s peace gambit derailed due to his inability to deliver sufficient concessions from either Trump or Kim to keep them moving forward during their February 2019 summit in Hanoi and Kim’s continued commitment to a strategic goal of legitimizing North Korea as a nuclear weapons state. Building on the September 2018 inter-Korean Pyongyang Declaration and military agreement, Moon and his team eagerly awaited an outcome from Hanoi in which North Koreans might allow the resumption of international inspections at North Korea’s main fissile material production site at Yongbyon in return for partial sanctions lifting. But the no-deal Trump-Kim summit in Hanoi marginalized Moon and resulted in a dramatic deterioration in inter-Korean relations.

A second source of stress in the U.S.-South Korea relationship has revolved around the shared challenge of how to manage China’s rise. Moon has sought China’s understanding, cooperation, and support for a peace process with North Korea, but the Trump administration has increasingly identified China as a potential adversary, trade cheat, and challenger to U.S. primacy in East Asia. As Sino-U.S. tensions have grown, the space for South Korea to balance between its economic dependence on China and security alliance with the U.S. has shrunk, constraining South Korea’s ability to avoid making choices between Washington and Beijing. South Korean angst has risen over U.S. pressure to join the Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy, while China has pressured South Korea to join its Belt and Road Initiative to build out infrastructure across Asia.

Despite a strong convergence of interests reinforced by North Korea’s nuclear threat and a continued mutual security commitment, Trump’s long-standing personal view of South Korea and other American allies as free riders has also raised tensions in the relationship. The two leaders successfully revised the Korea-U.S. Free Trade Agreement and closed the U.S. bilateral trade deficit with South Korea following Trump’s complaints that the agreement favored South Korea, but these revisions did not assuage his desire to raise South Korea’s financial support for the U.S. military presence on the peninsula.

South Korean conservative protesters participate in a pro U.S. and anti-North Korea rally on February 23, 2019 in Seoul, South Korea. (CHUNG SUNG-JUN/GETTY IMAGES)

Following a tense negotiation that produced a one-year deal in 2019 that increased South Korean contributions of on-peninsula costs for Korean local labor, logistics, and bases by eight percent to $860 million, the Trump administration upped its demands the following year to $4.6 billion – a five hundred percent increase that included U.S. off-peninsula costs in support of the deployment of forces and equipment necessary to provide for South Korea’s defense. South Korea stood firm in its insistence on keeping the longstanding formula for cost-sharing, seeking a multi-year deal with a thirteen percent increase that would bring South Korea’s annual contribution to around $1 billion per year. But the underlying source of friction in the relationship was Trump’s portrayal of the alliance as a relationship based on mercenary and mercantile incentives rather than on shared history, values, and interests.

Other sources of potential friction in the relationship revolve around Moon’s political objective of demonstrating South Korea’s freedom of action and ability to independently pursue its national security interests. Moon sought to implement a transition in Operational Control arrangements by the end of his term that would underscore South Korea’s full military partnership in executing war-time operations in the event of a Korean conflict. But Moon’s political deadline generated frictions over agreed-upon capabilities and circumstances that had to be achieved as a prerequisite for the transition, including a joint assessment that North Korea’s nuclear program was under control.

But the most dangerous source of political friction between Trump and Moon has remained the risk that Trump’s vision of “America first” would combine with a progressive “North Korea first” policy advocated by some Moon supporters to undermine decades of alliance-based cooperation aimed at deterring a common North Korean threat. The outcome of the fall 2020 U.S. presidential election will influence the magnitude and proximity of those risks, but they will not completely subside unless both the U.S. and South Korea can to stay in lockstep on how to most effectively deal with Kim Jong-un.

discussion questions

1. Can the U.S. hope to reach a deal with North Korea regarding denuclearization without the support of China? How can the U.S. bring China to the table?

2. If South Korea is forced to choose which relationship to maintain between the U.S. and China, which nation would be better for South Korean interests?

3. Should the U.S. shift focus toward dealing with a nuclear North Korea, or do you think denuclearization is still possible?

4. Do you believe that Kim-Jong-un would launch an unprovoked nuclear attack on either the U.S. or Japan? Does the U.S. risk provoking China

5. Do you think that South Korea can leverage their growing influence over pop culture (Kpop, Korean Dramas etc.) to a more prominent role in global politics? What has helped the U.S. maintain such a hold over global entertainment, and could these same mechanisms benefit the ROK?

suggested readings

Snyder, Scott A. South Korea at the Crossroads: Autonomy and Alliance in an Era of Rival Powers. 376 pg: Columbia University Press, 2018. In South Korea at the Crossroads, Scott A. Snyder examines the trajectory of fifty years of South Korean foreign policy and offers predictions and a prescription for the future. Pairing a historical perspective with a shrewd understanding of today’s political landscape, Snyder contends that South Korea’s best strategy remains investing in a robust alliance with the U.S…

Oberdorfer, Don. The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History, 560 pg. Basic Books, 2013. In this landmark history, veteran journalist Don Oberdorfer and Korea expert Robert Carlin grippingly describe how a historically homogenous people became locked in a perpetual struggle for supremacy -- and how other nations including the U.S. have tried, and failed, to broker a lasting peace.

Cha, Victor. South Korea Offers a Lesson in Best Practices Foreign Affairs Magazine, April 2020.

Cumings, Bruce. Korea’s Place in the Sun: A Modern History. 544 pg. W.W. Norton, 2005. Korea has endured a “fractured, shattered twentieth century,” and this updated edition brings Bruce Cumings’s leading history of the modern era into the present.

Demick, Barbara. Nothing to Envy: Ordinary Lives in North Korea, 336 pg. Random House, 2009. In this landmark addition to the literature of totalitarianism, award-winning journalist Barbara Demick follows the lives of six North Korean citizens over fifteen years—a chaotic period that saw the death of Kim Il-sung, the rise to power of his son Kim Jong-il (the father of Kim Jong-un), and a devastating famine that killed one-fifth of the population.

Kim, Suki. Without You, There Is No Us: Undercover Among the Sons of North Korea’s Elite 320 pg. Crown, 2015. Without You, There Is No Us offers a moving and incalculably rare glimpse of life in the world’s most unknowable country, and at the privileged young men she calls “soldiers and slaves.”.

Don’t forget: Ballots start on page 104!!!!

To access web links to these readings, as well as links to global discussion questions, shorter readings and suggested web sites,

GO TO www.fpa.org/great_decisions

and click on the topic under Resources, on the right-hand side of the page.