Chapter 4

The Authoritarian and the Philosopher: John Adams and Thomas Jefferson

IN THIS CHAPTER

Helping create a new country: Adams

Helping create a new country: Adams

Contributing to the nation’s intellectual and territorial expansion: Jefferson

Contributing to the nation’s intellectual and territorial expansion: Jefferson

This chapter deals with two presidents who were also founding fathers, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. Without either of these prominent men, the United States would not be the same country it is today. Adams set the foundation for independence by tirelessly working in Europe as a diplomat, getting the support of France in the Revolutionary War. Jefferson wrote the Declaration of Independence, setting the foundation for our modern-day form of government. As president, Adams turned authoritarian and tried to silence his opposition: This left a dark stain on his presidency. Jefferson, on the other hand, turned out to be one of our greatest presidents. One of his greatest accomplishments was the Louisiana Purchase of 1803.

Founding the Country and Almost Destroying It: John Adams

Unlike Washington, Adams didn’t need the military to help him move up the social ladder. After attending the finest schools, Adams became one of the great minds of his times. Today he is considered one of the greatest political thinkers in U.S. history. He still has an impact on the field of political philosophy.

Adams’s early career

Adams’s legal career proved to be his way into politics. In 1765, Great Britain enacted the Stamp Act, a tax on all legal documents, contracts, and even newspapers, to collect more money from the colonies. Instead of openly protesting, Adams sat down and drew up a complicated legal defense. He claimed that because the colonies were not represented in the British parliament, they didn’t have to pay the tax. Suddenly the name John Adams was a household name in the colonies. When the British repealed the Act in 1766, a lot of credit went to Adams.

Adams was so famous that the British tried to bring him over to their side. He rejected an offer to become advocate general in the British court system in the colonies. He chose instead to rebel against British oppression.

Believing in principles

As a supporter of U.S. independence, Adams didn’t mind peaceful protests to British rule. He didn’t approve of violence, however. In 1770, the Boston Massacre, which started as a demonstration against the British, got out of hand. Five people were killed when British soldiers opened fire on the protestors. Rejecting violent protest, Adams not only defended the soldiers, he got them acquitted.

Adams’s reputation rose. People saw him not only as a patriot, but also as a man who believed in the law and was unwilling to compromise his principles.

Entering politics

In 1773, Adams became one of the most vocal supporters of the Boston Tea Party. (See Chapter 3.) At the same time, he wrote a series of articles criticizing British policies. When the colonies held the first Continental Congress in 1774 to discuss what to do about British oppression, Adams attended as a delegate representing Massachusetts.

The first Continental Congress accomplished nothing. By the time the Congress met again in 1775, Adams and many of his colleagues and neighbors were ready for an armed resistance. John Adams proposed establishing a continental army to oppose Britain. He further recommended that Colonel Washington from Virginia should be put in charge of the new military force.

Declaring independence

At the second Continental Congress in 1775, Adams called for passing a declaration of independence and chaired a special committee formed to produce such a declaration.

Thomas Jefferson, a delegate to the Congress from Virginia, wrote the declaration, and Adams presented it to the Continental Congress. The Congress signed the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776.

Representing the new country

Adams’s major contributions to the founding of the United States didn’t come during his presidency — they came before he assumed the office. In his own way, Adams was as important to the revolution as George Washington. While Washington won on the battlefield, Adams succeeded in diplomacy. Without Adams’s efforts, the fledgling government wouldn’t have had a treaty of friendship and alliance with France and wouldn’t have received financial support from the Netherlands.

Acting as chief diplomat

With the Revolutionary War in full force, Adams played the role of diplomat during his next series of missions. The Continental Congress sent him to France in 1777 to gain French support for the new country. Not only did France recognize the newly established United States, but it also signed a treaty of friendship. Not satisfied with his successes, Adams traveled to the Netherlands to set the foundation for future financial support for the United States.

After a brief stint at home in 1778, during which he wrote the constitution for the state of Massachusetts — which is still in force today — Adams went back abroad.

This time, Adams traveled to Paris to work on a peace treaty between Britain and the United States. At first, his attempts were fruitless. So he traveled to the Netherlands. This time he succeeded. Not only did he secure a $42 million loan, but he also got the Dutch to agree to recognize the newly formed United States. He then went back to Paris to negotiate with representatives of the British crown. After long negotiations, Adams, Benjamin Franklin, and John Jay worked out the Treaty of Paris, which ended the Revolutionary War in 1783 and established U.S. independence for good.

With Adams so successful as a diplomat, the new U.S. government asked him to stay in Europe and become the U.S. representative to Great Britain. (The government at this point was run according to the provisions in the Articles of Confederation — Chapter 1 has more on the country’s founding.) He accepted the position and stayed in Britain until 1788. When he returned to the United States, he found out that he was one of the candidates considered for the presidency. He thought that he had no shot at winning, so he ignored the nomination.

Becoming vice president

In February 1789, the first Electoral College (see the “The Electoral College” sidebar in Chapter 1 for information on this) in U.S. history assembled to choose the first president and vice president. Each elector was given the opportunity to cast two ballots. Whoever received the most votes became president. The person who came in second became the new vice president. To his great surprise, Adams was selected vice president of the United States.

Although he was loyal to Washington, Adams didn’t shy away from conflict. He openly participated in the conflict between Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson (the “The first party system” sidebar in Chapter 3 explains the issues involved), in turn setting the foundation for our present political party system. Adams sided with Hamilton on the issues.

Adams was afraid of the public — especially because of the excesses of the French Revolution, where more than 20,000 members of the French political and social elite were killed — so he favored a stronger central government to maintain law and order. He felt more aligned with Great Britain than with France, and he favored the British in foreign policy. In the realm of economics, Adams believed in limited protection for the slowly developing U.S. industries. All of these political views made him a Federalist. He soon found himself facing off with Jefferson on major issues.

Running for president

To the surprise of many, President Washington didn’t run for a third term in 1796. Multiple candidates from both of the newly formed political parties ran for the office.

The Federalists favored two candidates — John Adams and Thomas Pinckney — while the Democratic-Republicans united behind Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr. Right away, Adams and Jefferson emerged as the front-runners. When the final tally came in, the election was close, and all four candidates received Electoral College votes. Adams came in first, winning 71 Electoral College votes. Jefferson received 68 votes, and Pinckney received 59 votes. Burr finished last with 30 votes. Adams was elected the second president of the United States.

The 12th Amendment to the Constitution, ratified in 1804, altered the process, allowing members of the Electoral College to cast two ballots — one for president and one for vice president.

President John Adams (1797–1801)

As the first president from the northern colonies (Massachusetts), Adams did an admirable job of continuing to provide legitimacy for the country. Adams was often criticized as being authoritarian and unable to tolerate criticism. His presidency was characterized by the Alien and Sedition Acts, which heavily undermined personal freedom in the United States.

John Adams (shown in Figure 4-1) was inaugurated on March 4, 1797. He faced a range of problems right away.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

FIGURE 4-1: John Adams, 2nd president of the United States (1797–1801).

Having problems with France

The French believed that the United States owed its independence to France’s efforts, and they expected the new country to support them in their current fight against the British. Washington’s decision to remain neutral annoyed the French. In an effort to punish the United States, France started attacking and seizing U.S. ships in early 1797. Within months, France had seized 300 U.S. ships.

This diplomatic insult prompted the United States Congress and the public to prepare for war with France. Congress voted to end all treaties with France and established the Department of the Navy. Adams asked Washington to take command of the U.S. military one more time; Alexander Hamilton became Washington’s second in command.

In the winter of 1799, the conflict turned violent. A U.S. frigate, the Constellation, successfully captured a French warship. War now seemed imminent.

Facing a crisis at home

After Jefferson’s departure, the Democratic-Republicans refused to collaborate with the Federalists. They even accused them publicly of trying to reestablish the monarchy. The Federalists, in turn, claimed that the Democratic-Republicans were ready to initiate a revolution in the United States and destroy democracy. President Adams became so alarmed that he started preparations to defend the presidential mansion (located in Philadelphia until 1800) against an attack.

LIMITING CIVIL LIBERTIES

Adams and the Federalists felt that the country couldn’t prepare for war with constant dissent and criticism by the Democratic-Republicans. To deal with the problem, the Federalist majority in Congress passed the Alien and Sedition Acts, which severely limited the ability of U.S. citizens to criticize the government. (See “The Alien and Sedition Acts” sidebar for details of these acts.)

The Federalists thought that they were now in a secure position to dominate the country and start a war. However, the acts backfired. The average citizen didn’t see the need for the acts and even feared that they undermined democracy in the United States. Furthermore, major leaders, including Jefferson and Madison, criticized the acts publicly. Two states, Kentucky and Virginia, issued statements — written by Jefferson and Madison, respectively — refusing to enforce the acts and threatening to nullify them. Virginia, fearing a federal attack, mobilized its state militia for a possible showdown with Adams. Federalist Hamilton, now in charge of the federal military, was ready to send in the troops.

AVOIDING CIVIL WAR

With the outbreak of a civil war looming, Adams looked for a political solution. This time, he sought to make peace with France himself. He ignored Congress and even his own cabinet, and sent one more delegation to France. He also demobilized the federal military to avoid a confrontation with Virginia. To top it off, Adams fired two of his cabinet members — Secretary of State Timothy Pickering and Secretary of War James McHenry. He distrusted them because they were loyal to Hamilton. In retaliation, Hamilton did his best to undermine Adams in the upcoming presidential elections.

The negotiations with France proved successful, and in October 1800, the two countries signed a treaty. France recognized U.S. neutrality, and the United States didn’t insist that France pay reparations for the U.S. ships they seized.

Losing the presidency in 1800

The election of 1800 was a rematch between Jefferson and Adams. The outcome was very close — just as it was in 1796. The difference was Hamilton. Hamilton, who was angry with Adams, did his best to make sure that his own president lost the race. Right before the election, he published an article in which he called Adams mad and egotistical. The feud divided the Federalists, and Adams lost the race to Jefferson. The final tally gave Jefferson 73 Electoral College votes and Adams 65 votes.

Making an ungraceful escape

Adams was angry and disappointed at losing the presidency — he felt that he deserved to win reelection because he had so loyally served his country. He was so mad that he refused to attend his successor’s swearing-in ceremony. He and his wife actually snuck out of Washington, D.C., the night before Jefferson arrived to occupy the White House.

Switching parties at the end

After leaving office, Adams became a bitter enemy of Hamilton's. In 1812, Adams and his son, John Quincy Adams, left the Federalist Party to become Democratic-Republicans. At the same time, Adams made peace with Jefferson. The renewal of their friendship helped restore Adams’s reputation with the citizenry.

Adams lived long enough to see his son, John Quincy, win the presidency in 1824. Adams and Jefferson died on July 4, 1826, exactly 50 years after the Continental Congress passed the Declaration of Independence that both men had worked on.

Master of Multitasking: Thomas Jefferson

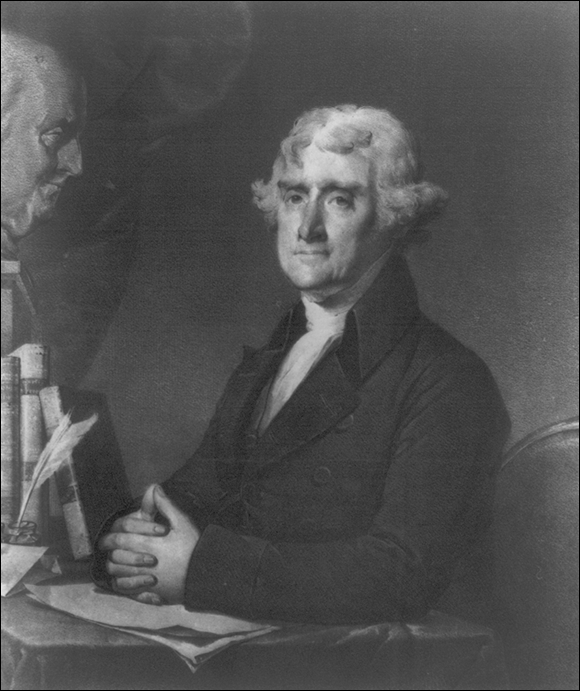

Many consider Thomas Jefferson, shown in Figure 4-2, to be one of the most brilliant men who ever lived. Without any doubt, Jefferson was one of the greatest thinkers in the history of the world. He was not only a politician, but also a philosopher, a diplomat, a scientist, an inventor, and an educator. Without Jefferson, there wouldn’t be a Declaration of Independence or a Louisiana Purchase. Like Washington and Adams, Jefferson truly deserves the title “founding father.”

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

FIGURE 4-2: Thomas Jefferson, 3rd president of the United States (1801–1809).

Jefferson’s early political career

In 1768, Jefferson was elected to the Virginia legislature. Aided by his education and writing ability, Jefferson became a powerful member of the legislature within a few years.

In 1769, Jefferson joined fellow legislator George Washington and others in condemning the Townshed Act (see Chapter 3) and embraced the cause of independence.

The British-appointed governor of Virginia shut down the legislature in response to their defiance. The legislators just moved their meeting place to a local tavern and continued their business.

After the passage of the Intolerable Acts in 1774 (see Chapter 3), Jefferson went to work. He wrote a lengthy document entitled “A Summary View of the Rights of British America,” in which he provided a philosophical attack on the British right to govern the American colonies.

Jefferson was chosen as a delegate to the first Continental Congress, but he never made it to Philadelphia; he became sick on the way. He did send his documents to the first Continental Congress, which made quite an impact. Thomas Jefferson became a household name in the colonies, and his intellectual abilities became famous. Jefferson was now a well-known radical. His path toward becoming a founding father was set.

Writing the Declaration of Independence

In 1775, Jefferson became a member of the second Continental Congress. As a delegate in Congress, Jefferson became a member of the committee charged with drawing up a declaration of independence for the American colonies. John Adams, a fellow committee member, asked Jefferson to write the declaration for the committee. After Jefferson finished the task, he sat down with Adams and Benjamin Franklin and made final corrections to his draft. In July 1776, the revised declaration was presented to the full Congress. On July 4, 1776, the Continental Congress officially adopted the declaration. A new country was born.

Failing as governor and succeeding as diplomat

Jefferson was elected governor of Virginia and started his term in 1779. He hated the job — because the Virginia constitution gave all powers to the legislature — and he was very unsuccessful at it. When the British attacked Richmond, the capital, Jefferson fled, taking no measures to defend the city. In 1781, he retired after declaring himself sick and tired of politics. He refused to serve a second term as governor, even after he was reelected.

In 1783, the Treaty of Paris ended the Revolutionary War. Jefferson had reentered politics following the death of his wife the year before, and he was serving in the Continental Congress. He became the ambassador to France when Benjamin Franklin retired from the post.

Jefferson, who was fluent in French and enjoyed a solid reputation in Europe, proved to be a natural diplomat. He enjoyed the good life in France and served as ambassador for the next four years. He was in France during the start of the French Revolution in 1789. He initially agreed with the basic principles behind the revolution, but later condemned the violence and slowly moved away from supporting the new, revolutionary government.

Serving under Washington and Adams

Upon his return from France in 1789, Jefferson was asked by the newly elected president, George Washington, to serve as his secretary of state. Jefferson accepted the position, but he soon started clashing with the secretary of the treasury, Alexander Hamilton. (Their conflicts led to the country’s first new political parties, which I explain in the sidebar “The first party system” in Chapter 3.)

The first big clash occurred over the issue of a national bank. Hamilton wanted to create a national bank, while Jefferson believed that the states should control the banking structures. Jefferson lost the battle when Washington sided with Hamilton. Continuing conflicts with Hamilton and Washington prompted Jefferson to resign in 1793. He thought that he had retired to his estate near Richmond for good. Boy, was he wrong.

In 1796, Jefferson reluctantly accepted the Democratic-Republican nomination for the presidency. It was a position he didn’t want. He didn’t even campaign for office, instead staying home on his plantation. To his great surprise, he came in second, losing to Adams by only three Electoral College votes. Under the Electoral College laws in effect at the time, the person who came in second became vice president. Jefferson, a Democratic-Republican, became vice president to the Federalist president Adams — not a good foundation for political success.

Jefferson started to oppose Adams and the Federalists openly from his plantation, called Monticello. He went so far as to draft the Kentucky Resolution, which opposed the federal government and the Alien and Sedition Acts.

President Thomas Jefferson (1801–1809)

With the 1800 election approaching, Jefferson decided to run again. This time he took the race seriously, believing that he had to save democracy from the Federalists. He defeated the incumbent Adams.

Jefferson then freed everybody who was in jail because of the Alien and Sedition Acts. He refused to renew the acts. The acts quietly expired the same year. (See the sidebar earlier in this chapter, titled “The Alien and Sedition Acts,” for more information.)

Attempting to be frugal and balance the budget, Jefferson cut the size of the federal bureaucracy, including the military, and abolished several taxes, including the tax on the distilling of liquor that had prompted the Whiskey Rebellion back in 1794 (see Chapter 3).

Expanding the country: The Louisiana Purchase

Jefferson’s greatest accomplishment as president is undoubtedly the purchase of the Louisiana Territory from France.

France acquired the Louisiana Territory in 1682 and gave it to Spain in 1762. With France’s renewed power in the late 18th century, Jefferson expected the territory to be returned to France. Jefferson turned out to be correct: France reacquired the territory in 1802.

The weak Spanish empire constituted no threat to U.S. territorial interests, but the French empire was a different story. Jefferson sent his friend James Monroe, the former governor of Virginia and future president, to Paris to attempt to buy New Orleans from France.

The French shocked Monroe by offering to sell the whole Louisiana Territory for a measly $15 million. Jefferson rejoiced and signed the treaty setting the terms for purchase. On December 20, 1803, the Senate approved the purchase, and the United States doubled in size overnight. Jefferson successfully added 828,000 square miles to the country. The territory included what would become parts of Wyoming and the following states:

Arkansas |

Colorado |

Iowa |

Kansas |

Louisiana |

Minnesota |

Missouri |

Montana |

Nebraska |

North Dakota |

Oklahoma |

South Dakota |

Facing the British again

By the turn of the century, the British navy, famous for mistreating sailors, faced mass desertions and a serious manpower shortage. The solution the British Navy came up with was to not only recapture their own deserters but to impress, or forcefully take, U.S. sailors to serve on British ships.

By the time Jefferson started his second term, British ships were stopping U.S. ships and taking U.S. citizens to serve in the British navy. Literally thousands of U.S. sailors were kidnapped to serve on British ships.

In 1807, a U.S. frigate, the Chesapeake, encountered a British war ship. When the crew of the Chesapeake refused to let the British search their ship, the British opened fire on it. This was the last straw for the U.S. Congress and President Jefferson.

By 1809, the U.S. public had enough: National income fell by 50 percent in just two years. One of Jefferson’s last acts as president was to repeal the Embargo Act. He replaced it with the Non-Intercourse Act, which banned trade only with Britain and France — the French had also seized U.S. ships.

Keeping busy in retirement

By the 1808 elections, Jefferson had enough of politics. He also wanted to abide by the two-term limit established by Washington, so he chose not to run for reelection. At the age of 65, Jefferson intended to spend the rest of his life pursuing intellectual endeavors.

While enjoying his true loves, reading and studying, Jefferson still had time to found the University of Virginia. (He even designed the campus himself.) Jefferson insisted on the acceptance of all students, rich or poor. His dream of public education, at least at the university level, came true.

Adams wanted Washington to be in charge of the newly created continental army for political reasons. He wanted to make sure that the Southern colonies supported a war of independence. Support was easier to garner with a Southerner in charge of the military.

Adams wanted Washington to be in charge of the newly created continental army for political reasons. He wanted to make sure that the Southern colonies supported a war of independence. Support was easier to garner with a Southerner in charge of the military. John Adams and Thomas Jefferson were the only future presidents to sign the Declaration of Independence.

John Adams and Thomas Jefferson were the only future presidents to sign the Declaration of Independence. Adams didn’t enjoy his role as vice president. He often complained in private of how insignificant his position was, calling the vice presidency the “most insignificant position ever invented.”

Adams didn’t enjoy his role as vice president. He often complained in private of how insignificant his position was, calling the vice presidency the “most insignificant position ever invented.” Article 2 of the Constitution prescribes that the person with the highest number of electoral votes becomes president, while the second-highest vote-getter serves as vice president. Thus, for the only time in U.S. history, the president and vice president belonged to different political parties.

Article 2 of the Constitution prescribes that the person with the highest number of electoral votes becomes president, while the second-highest vote-getter serves as vice president. Thus, for the only time in U.S. history, the president and vice president belonged to different political parties. Jefferson’s first term was a big hit with the U.S. public. It is widely considered to be one of the most successful terms of any president in U.S. history. Unfortunately, he couldn’t keep it up. After easily winning reelection in 1804, Jefferson had a tough time with the problems that started during his second term.

Jefferson’s first term was a big hit with the U.S. public. It is widely considered to be one of the most successful terms of any president in U.S. history. Unfortunately, he couldn’t keep it up. After easily winning reelection in 1804, Jefferson had a tough time with the problems that started during his second term.