Chapter 22

The Career Politician and the Peanut Farmer: Ford and Carter

IN THIS CHAPTER

Becoming president after a resignation: Ford

Becoming president after a resignation: Ford

Bringing humanitarianism to the presidency: Carter

Bringing humanitarianism to the presidency: Carter

Presidents Ford and Carter were similar in style and character. Both were honest men who showed character and integrity in office. Both dealt with the aftermath of Vietnam and Watergate and restored credibility to the White House. The two were also similar politically: Ford was a moderate Republican, and Carter was a moderate Democrat.

Ford and Carter both had their problems in office. During Ford’s presidency, Vietnam was lost to communism, and Ford issued the controversial pardon of former President Nixon. Carter tried to pursue a moral, humanitarian foreign policy, which ended in failure when the Soviet Union took advantage of perceived weaknesses in U.S. foreign policy.

Today, President Carter is recognized as a great humanitarian. Carter goes on peace missions all over the world. President Ford became the grand old man in the Republican Party until his death in 2006, at the age of 93. Both men are/were great human beings, but their presidencies were merely average.

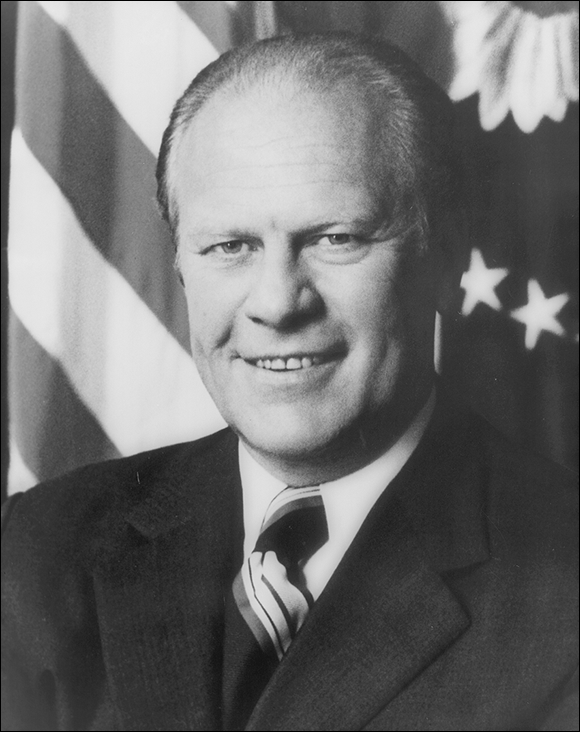

Stepping in for Nixon: Gerald Ford

Gerald Ford, shown in Figure 22-1, became president by default. He never wanted to be president. Ford actually turned down the vice presidency when Nixon asked him to be his running mate in 1968. Ford’s great desire was to become Speaker of the House. When he didn’t receive the position in 1972, he planned to retire in 1976. Fate intervened.

Returning home, he married Elizabeth “Betty” Bloomer Warren, a model and professional dancer. Betty Ford was one of the most controversial and beloved first ladies in U.S. history. She favored abortion rights and supported the Equal Rights Amendment, which the Republican Party opposed. Her fight with breast cancer increased public awareness of the disease. After leaving the White House, she revealed her addiction to painkillers and alcohol and proceeded to establish the Betty Ford clinic in California, which has become a favorite treatment center for movie stars and politicians with dependency problems.

When Vice President Spiro Agnew resigned, Nixon needed a replacement fast. He chose Ford. Just a few months later, Ford suddenly found himself president of the United States, without ever running for the office.

Ford did what he thought was right and did his best to restore honesty and prestige to the office of the presidency. For this he deserves credit.

It isn’t really fair to rank Ford’s presidency, because he served just a little over two years in office. Taking his whole political career into account, he can be rated as a great politician and an average president.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

FIGURE 22-1: Gerald Ford, 38th president of the United States.

Ford’s early political career

Ford joined the Republican Party in 1940. He shared his stepfather’s opposition to big government and support for U.S. isolationism in foreign policy. However, Ford changed his views on foreign policy after serving in the military. He now believed that the United States needed to be involved in international affairs.

In 1948, the local Republican Party in Grand Rapids, Michigan, approached Ford and asked him to challenge incumbent Republican Congressman Bartel Jonkman, an isolationist, in the primary. Ford, running on the strength of his war record, beat Jonkman easily. He then cruised to victory in the general election and began a long, distinguished Congressional career.

Serving in Congress

Ford rose quickly through the Republican ranks. In 1963, he became the chairman of the House Republican conference. In 1965, he took over as the House minority leader. Now he had his eyes set on the speakership. For Ford to get the position, however, the Republicans had to win a majority in the House, because the majority party selects the Speaker. Ford expected Nixon’s landslide reelection in 1972 to help the Republicans get the majority in the House, but that didn’t happen. So Ford decided to make it his last term in office.

Being approved for the vice presidency

In 1973, President Nixon’s vice president, Spiro Agnew, resigned because he had been involved in a bribery scandal (see Chapter 21). Nixon needed a replacement quickly. He considered Ronald Reagan, the governor of California, but opted for Ford. Ford had good ties to Congress, was well liked and respected by his peers, and could easily win confirmation.

The Senate ratified Ford by a vote of 92 to 3. The House followed suit and approved Ford by a vote of 387 to 35. Gerald Ford became the vice president of the United States on December 6, 1973.

Stepping into the presidency

As the new vice president, Ford soon became involved in the Watergate scandal (President Nixon and the Watergate scandal are covered in Chapter 21). Ford had to publicly defend the president, even though he privately believed that Nixon was guilty.

As the Watergate affair continued, it became increasingly clear to Ford that he might become president. Early in the summer of 1974, Ford’s personal advisor Phil Buchen began to set up a transition team, without Ford’s direct knowledge, just in case.

On August 8, 1974, President Nixon announced his resignation to the U.S. public. One day later, Gerald Ford became the new president. He had an unenviable task ahead of him. He needed to reassure the nation and restore faith in the presidency.

President Gerald Rudolph Ford, Jr. (1974–1977)

On August 9, 1974, Ford addressed the nation to reassure the U.S. public. He announced that the long nightmare was over and that it was time to go on with politics as usual.

A month later, Ford destroyed his presidency for the good of the country when he announced that he had issued a full pardon to former President Nixon. The media and many U.S. citizens were incensed. Calls poured in, condemning Ford’s actions. His approval rating fell from 71 percent to 50 percent. Ford lost all the goodwill that he had accumulated in Congress. His presidency seemed doomed.

Taking on domestic problems

The 1974 Congressional election gave the Democratic Party an overwhelming majority in Congress. Now Ford faced a hostile Congress. Over the next two years, Congress overrode more than 20 percent of Ford’s vetoes, the highest percentage in over a century.

To make matters worse, the economy took a nosedive. Inflation skyrocketed, driven by increased government spending and an increase in the price of oil. Ford cut government spending to help combat the rise in inflation. By the time he left office, inflation had fallen from 11.2 percent to 5.3 percent.

The unemployment rate also rose. Ford cut taxes to stimulate the economy and create jobs. Congress, however, blocked his tax cuts until 1976; by then it was too late for them to have an impact on the 1976 elections.

To placate critics on the left, Ford proclaimed a full amnesty for draft dodgers. Draft dodgers were young men who either avoided the draft or deserted the military during the Vietnam War. Under Ford’s amnesty plan, these men would be welcomed back into the country if they completed two years of public or military service. Over 20,000 people applied for amnesty.

Dealing with foreign policy problems

When Gerald Ford assumed the presidency, the United States had withdrawn completely from South Vietnam. But the war between North Vietnam and South Vietnam continued.

In 1975, North Vietnam violated the peace treaty of 1973 (see the “Conflict in Vietnam” sidebar in Chapter 20) and invaded South Vietnam. Ford wanted to help South Vietnam, but Congress refused to go along. Within months, the South Vietnamese government fell, and all of Vietnam was now communist. More than 50,000 U.S. soldiers had died for nothing.

The Ford administration handled many other foreign policy events, including

- The Helsinki Accords: In 1975, 35 countries met in Helsinki, Finland, and ratified accords that recognized all post–World War II borders in Europe as legitimate. The Soviet Union, as part of the agreement, pledged to respect human rights and ease travel restrictions for Soviet citizens and foreigners traveling to the Soviet Union.

- The Vladivostock Agreements: Ford and Soviet Premier Brezhnev signed these agreements in 1974. The agreements amended the SALT I arms treaty (see Chapter 21) and allowed for only one antiballistic missile site per country.

Winning the Republican nomination and losing the presidency

In the fall of 1975, Ronald Reagan entered the race for the Republican presidential nomination. Reagan ran to the right of Ford, opposing the Helsinki accords and advocating a tough line against the Soviet Union. Reagan won several southern primaries. But in the end, Ford narrowly prevailed at the Republican convention. Ford picked Senator Robert Dole of Kansas for his vice-presidential running mate.

In the campaign against Democrat Jimmy Carter, Ford started out as the underdog. The economy was not doing well, and many people never forgave Ford for pardoning Nixon. His vice-presidential nominee, Robert Dole, came across as a bitter, mean-spirited man, labeling the Democratic Party the “party of warfare.”

Ford committed a major gaffe during the presidential debates. He said that Poland wasn’t under Soviet domination, when it clearly was. This error undermined his campaign.

At one point, Ford trailed Carter by over 50 points in the polls. He managed to close the gap considerably, losing by only 2 percentage points.

Retiring publicly

After leaving office in 1977, President Ford undertook many public activities. He taught at the University of Michigan, founded the American Enterprise Institute, a think tank that studies public policy, and wrote his memoirs while staying active in politics.

Ford campaigned for Republicans throughout the country. In 1980, he almost became Reagan’s vice-presidential candidate. He actively supported every Republican presidential candidate until his death in 2006.

In 1999, President Clinton awarded Ford the Presidential Medal of Freedom for his many years of service to the country. Ford suffered a minor stroke at the Republican convention in 2000 and died of heart disease at the age of 93 in 2006.

Sharing Faith and Principles: Jimmy Carter

Jimmy Carter, shown in Figure 22-2, was the Democrat least likely to win the presidency in 1976. He was the governor of a small southern state, Georgia, and had no national political experience. In earlier times, the lack of experience would have sunk any other candidacy. But, after the Watergate scandal in Richard Nixon’s term (see Chapter 21), the U.S. public was sick and tired of politics as usual. They wanted someone new — an outsider — with no ties to Washington.

Carter ran on an outsider platform. He promised to return morality to the White House and to fight corruption in the capital. Carter’s platform was good enough to win the presidency. However, as president, Carter paid a bitter price for being an outsider. He didn’t have the connections in Congress to get his agenda passed, even though his party controlled both Houses of Congress. A declining economy and a foreign policy crisis undermined Carter. He lost his reelection bid in 1980.

Carter’s early political career

Carter’s political career started in 1960, when he won a seat on a local school board in Plains, Georgia. Two years later, he was elected to the Georgia state senate. Carter appeared to have lost the race at first, but he challenged the results, claiming vote fraud. He won the case and the seat.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

FIGURE 22-2: Jimmy Carter, 39th president of the United States.

By 1966, Carter thought that he was ready for the governorship. He entered the race and finished a disappointing third. Carter didn’t take the loss lightly; he went into a major depression and thought that his political career was over. His sister encouraged him to find religion, and Carter became born again, turning himself into an Evangelical Christian. Encouraged, he ran for governor again in 1970.

Governing Georgia

Running for the presidency

As early as 1972, Carter wanted to be president. He established a campaign committee and had a detailed strategy drawn up. In 1974, the Democratic Party appointed Carter to head the Democratic National Campaign Committee, a committee in charge of raising money for Democratic candidates throughout the country. From there, he decided to make a run for the presidency.

In early 1975, Carter announced his candidacy. He was a virtual unknown, and nobody gave him much of a chance. But Carter prevailed. He campaigned hard and kept discussion of his position vague on various issues while calling for a return to morality and an end to corruption in the federal government. Carter’s platform resonated with a public that had recently dealt with Vietnam and Watergate. Carter won 17 of the 30 primaries.

At the Democratic convention, Carter received the nomination on the first ballot. To placate northern liberals and unions, Carter nominated liberal Minnesota Senator Walter Mondale as his vice president.

During the campaign, Carter blew a huge lead in the polls. But he managed to hang on to win the presidency. Much of his support came from African Americans and the southern states. Carter won the presidency with 297 electoral votes to Ford’s 240. (One elector cast a vote for Ronald Reagan, who was not a candidate.)

President James Earl Carter, Jr. (1977–1981)

Carter’s results as president were mixed. He had some successes, but at the same time, he experienced massive failures. One of his greatest mistakes was to make good on his campaign promise to rely on outsiders who didn’t have strong ties to Congress. Even though his party controlled both Houses of Congress, he had less success in dealing with Congress than did presidents who didn’t have that advantage — George H. W. Bush, for example.

Things started out well for Carter. On his first day in office, he pardoned all Vietnam draft evaders. He was able to get important environmental legislation passed, and he established the Department of Education to improve instructional standards throughout the United States.

Dealing with foreign policy issues

Carter attempted to base his foreign policy on human rights considerations. He cut off aid to friendly dictatorships if they violated human rights, which led to disastrous results. By 1978, the pro-American governments in Nicaragua and Iran had collapsed. The fall of the Shah of Iran in 1978 came back to haunt Carter. Major foreign policy events during the Carter administration include

- The Panama Canal Treaty: Despite objections by many U.S. citizens, Carter signed a treaty to return the canal to Panama by December 31, 1999. The United States reserved the right to defend the canal.

- The Camp David Accords: In September 1978, the crowning moment of the Carter administration’s foreign policy took place. Carter met with Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin and Egyptian President Anwar Sadat in Camp David, Maryland. After long negotiations, the Camp David Accords, which ended the state of war between Israel and Egypt, were finalized. Sadat and Begin won the Nobel Peace Prize for negotiating the accord.

- SALT II: Carter and Soviet Premier Leonid Brezhnev signed SALT II (Strategic Arms Limitations Talks) in 1979. The treaty imposed ceilings on strategic weapons for both countries. The Senate never ratified SALT II. Carter withdrew it from consideration when the Soviets invaded Afghanistan.

- The Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan: In 1979, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan to maintain a communist government in power. Carter reacted strongly, withdrawing SALT II from the Senate, boycotting the Olympics held in Moscow, and prohibiting the sale of grain to the Soviet Union. The Soviets stayed in Afghanistan until 1989, when troops were recalled.

- The Carter Doctrine: The Carter Doctrine stated that the United States would use military force to prevent the Soviet Union from expanding further into the Middle East.

Facing U.S. hostages in Iran

In 1979, the Shah of Iran, the major U.S. ally in the Middle East, was toppled by a Muslim fundamentalist regime headed by the Ayatollah Khomeini. Carter refused to help the U.S. ally.

On November 4, 1979, Iranian militants seized the U.S. embassy in Teheran, the capital of Iran — a clear violation of international law. After Carter protested, the Iranian government released all the women and minorities they had seized but continued to keep 53 white men hostage. Carter tried to negotiate the hostages’ release, but he failed.

In April 1980, Carter authorized a military special forces unit to go in and get the hostages out. The attempt failed when a sandstorm caused two choppers to collide, killing eight servicemen.

Carter was blamed for the failure of the rescue attempt. The ongoing hostage crisis contributed greatly to his defeat in his 1980 reelection bid. Republican Ronald Reagan, while campaigning for the presidency, openly threatened Iran with a military strike unless the hostages were released. Iran released the hostages on January 20, 1981 — the day Reagan was inaugurated.

Handling problems at home

Most of Carter’s domestic problems centered on the issue of energy. In 1979, OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) increased oil prices dramatically. This led to inflation. By 1980, loan interest rates hit 20 percent. Most people were unable to finance homes and cars. Carter took the blame for the high interest rates.

On the bright side, Carter managed to pass legislation that encouraged the development of alternative energy in an effort to decrease dependence on foreign oil. Unfortunately, these programs were dismantled by his successors.

The Republicans nominated Ronald Reagan, the former governor of California, on the first ballot. His vice-presidential nominee was George H. W. Bush, the former head of the CIA and former Texas congressman. The Republican ticket was formidable, indeed.

Losing his reelection bid

In 1980, Carter was forced to campaign on a liberal platform. He also had a lot of political baggage hanging over him, especially the hostages still held by Iran. Reagan, on the other hand, campaigned on an agenda of making the United States great again. Carter hoped that he would have an advantage in the debates. However, Reagan, who was a former actor, excelled at the debates and bested Carter.

When the election results came in, Carter had lost in a landslide, winning just 41 percent of the vote to Reagan’s 51 percent. In addition, the Democrats lost control of the Senate for the first time since the 1950s.

Carter left office in January 1981, with his presidency considered a failure. He himself was considered a weak, ineffective president.

Retiring but not retreating

After leaving office, Carter proceeded to restore his reputation. He founded the Carter Center at Emory University to study democracy and human rights. Carter became an even more vocal advocate of human rights throughout the world.

Carter has traveled extensively, monitoring elections in many countries, and has served as a special peace emissary on more than one occasion.

Carter and his wife Rosalynn also participate in Habitat for Humanity, where they don’t just raise money but actually help build low-income housing with their own hands.

In 1999, President Clinton awarded Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter the Presidential Medal of Freedom for their humanitarian service, and in 2002 Jimmy Carter received the Nobel Peace Prize for bringing peace to the Middle East while president. Today, Jimmy Carter is one of the most respected individuals not just in the United States but in the world. What a way to restore one’s reputation.

Ford’s presidency is characterized by two major events: His controversial pardon of former president Nixon, which cost him reelection in 1976, and the loss of South Vietnam to communist North Vietnamese forces.

Ford’s presidency is characterized by two major events: His controversial pardon of former president Nixon, which cost him reelection in 1976, and the loss of South Vietnam to communist North Vietnamese forces. Ford served in the House of Representatives for the next 25 years. As a congressman, Ford was very conservative on defense issues — he voted to increase the defense budget and became a staunch anti-communist. At the same time, he consistently supported civil rights legislation.

Ford served in the House of Representatives for the next 25 years. As a congressman, Ford was very conservative on defense issues — he voted to increase the defense budget and became a staunch anti-communist. At the same time, he consistently supported civil rights legislation. Under the provisions of the 25th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, the president has to submit the name of a new vice president to Congress if the former vice president dies or resigns. Congress then has to approve the president’s choice.

Under the provisions of the 25th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, the president has to submit the name of a new vice president to Congress if the former vice president dies or resigns. Congress then has to approve the president’s choice. President Ford is the only person in U.S. history to serve as both vice president and president without being elected to either office. He was appointed to both positions.

President Ford is the only person in U.S. history to serve as both vice president and president without being elected to either office. He was appointed to both positions.