CHAPTER 8

The Rat

Jarvey felt as if he were suffocating. Everything had gone absolutely dark, darker than midnight. He felt Zoroaster’s hand shove him back against the brick building, and he stood gasping for air.

A moment later, boots clapped on the cobblestones. “Which way did he go?” a hoarse voice demanded.

“Can’t see ’im now,” the other tipper returned. “Must’ve cut across there and into Crooked Alley.”

“You sure?”

“No place on the street for ’im to hide, is there? Come on!”

Running footsteps faded in the distance, died away. The hand on Jarvey’s arm dragged him sideways, and he stumbled, unable to see where they were going. Then he heard Zoroaster chant again, and in a blinding flood the brassy daylight returned.

Zoroaster stood beside him, his left hand grasping Jarvey’s right arm, his right hand flat on the alley wall. The man had changed. His hair had been cropped short, and he wore ragged gray clothing, like a commoner. “It’s lucky I’ve been watching for you,” he said. “Are you all right?”

“Wh-what did you do?” Jarvey asked.

“I made us both invisible,” Zoroaster snapped. “We’ll have to move. Midion can detect magic. You did a bit a few minutes ago, and I just did considerably more.”

“Invisible?” Jarvey gasped. “I couldn’t see!”

“Of course not. If you are invisible, the retinas of your eyes are transparent. If that is so, no image can form upon them. That is a disadvantage of invisibility. Follow me.”

They trotted down the alley, into another street, and then beneath a short arched bridge, where they paused. Jarvey hadn’t realized how out of breath the pursuit had made him. His legs felt as if the bones had become jelly. “What—what happened after that night?” he asked. “Why did you run away?”

“I ran because Tantalus knew you had left with me, and because I had seen the Grimoire,” Zoroaster said. “He does not know it is here. He must not know. If he were close to capturing me, I would choose death rather than giving him the knowledge of the book’s whereabouts.” Zoroaster passed a hand across his face, as if he were terribly tired. “What did you do? I felt something of it, the energy, but not what kind of spell you performed.”

“I—I unlocked a lock,” Jarvey said. “My friends had been caught, and I made the lock unfasten itself.”

“How?”

“I don’t know,” Jarvey confessed. “I was holding it, and I kept telling it to unlock. Not out loud, I just thought it. And sparks shot from it, and then it just opened.”

“Extraordinary,” Zoroaster said. “Most beginners cannot focus without the discipline of a spoken spell.”

“Then once before—” Jarvey hesitated, then told of how he had climbed up the narrow alley and how the tipper had looked straight at him without appearing to see him. “I thought I was invisible then,” he finished.

“No,” Zoroaster said. “You were simply not noticed—that is not the same thing as being truly invisible. You may have caused the tipper to become inattentive, to ignore you. That is easy to do with one person, but almost impossible with two or more.”

“Listen,” Jarvey said, “you were going to find my mom and dad. Have you—”

“No.” The word was harsh and final. “No, Jarvey, I have not found them. Believe me, I have inquired every way I know how, and that includes some ways even Tantalus could not guess. Only one person can find them now.”

“Who?”

“You,” Zoroaster said. “I will have to ask you not to try, though. Not yet, anyway.”

“What?”

“Because you will have to use the Grimoire.” Zoroaster had lowered his voice to a harsh whisper. “And I do not know what opening that cursed volume would do, here, in the very land it shaped for Tantalus Midion. I have been in its presence five times, six counting the time I saw it in your hands. I lack the courage of some sorcerers, however. I have never had the courage to open the book. For in opening it, in reading the dire spells it contains, one’s will may be warped, one’s soul turned toward evil. The promise of power is a terrible temptation.”

“I can’t open it,” Jarvey said. “I’ve tried.”

“Don’t try again! Not unless I tell you to do so.”

Jarvey stepped away from him, balling his fists at his sides. “If I can find my mom and dad by opening the book, I’ll open it!”

“I’m not sure you can,” Zoroaster said. “Yet there seems to be no other way. Listen: Tantalus’s men have come close to me, far too close for my peace of mind. I may have to leave Lunnon, to go outside.”

“Outside?”

“Into the real world. Yes, I can move back and forth, though it is very dangerous. If I must, then Tantalus will know I have left, and he may work spells to block me from returning. Yet I know of no other way to find the essential spells that might allow you to open the Grimoire and survive. Do you know Green Park, at the corner of Broad and Brick streets?”

“I could find it.”

“At the center of the park is a fountain. If I can learn what I need to know, I will meet you there.”

“How will I know when to meet you?”

“You will know,” Zoroaster said. “I will get word to you. No matter where you are. You will know.”

“But what if—” Jarvey broke off, his mouth hanging open. Zoroaster was gone. He had not exactly vanished, had not faded away. It was as if he had been only a projected picture, and someone had switched the projector off.

Jarvey backed out from the shadows beneath the bridge. He wanted to be with someone he knew. He climbed the bank up to the bridge and set off for the Den. It was his only home now.

“We’re movin’. Now,” Betsy said grimly. “This place is too hot for us.”

Jarvey groaned. He was hungry and his muscles ached from fatigue and effort. Everyone had turned up at the Den by twilight, and now Betsy walked back and forth, speaking in an angry voice. “There was too many tippers on the wharves today. Something got their suspicions up, and if that’s happened, we’ve got to find another snug. I know one we can reach tonight, but we have to start now. Jarvey, get ready.”

Jarvey took the Grimoire from its hiding place and tucked it inside his shirt.

Someone nudged Jarvey from behind. “That was too close, mate.”

Jarvey wrinkled his nose at the blast of bad breath. It was Charley. “Yeah, it was,” Jarvey whispered back.

“There’s a rat here, you know, Jarv.”

“What?” Jarvey knew there were real rats in Lunnon—some of the kids had talked about hard times when they had hunted down rats for food—but somehow he didn’t think that was what Charley meant.

“A rat. Somebody peached, told them tippers we was going to be workin’ the waterfront today. That’s why so many of them was there waitin’ for us. Didn’t you think that was strange, like?”

“I didn’t know what to think,” Jarvey said. “I just wanted to get away from them.”

“You watch Bets,” Charley said in a low voice. “I think this might have been a put-up job. Like maybe she’d get herself caught, and you’d swap the book for her, or something.”

Jarvey felt even colder. His throat tightened. He had thought of trading the book for his friends’ freedom, but—Betsy?

Charley jerked his head toward Betsy, who was busy with the other kids. “Keep an eye out, is all. If there’s a rat among us, just know you can never trust a rat.”

“All right, then,” Betsy was saying. “We’ll split up. You leaders know where to take your groups. We’ll take it slow. Charley, you’ll take the first one, then Puddler will go, and last of all me. If it gets safe to join together again, I’ll get word to Charley, and he’ll see that Puddler hears. Ready to go, then?”

“Come with me,” Charley suggested to Jarvey.

“He’s with me,” Betsy said sharply. “Get on with you now.”

“Don’t burst a blood vessel,” Charley said easily. “Hi, you lot—with me. Come along, then.”

Pattering feet in the twilight as Charley’s group dropped down into the drain and scurried away. When their echoes had died, Betsy said, “Right, then. Puddler, you’re next. Along with you, and remember to keep to the shadows.”

Jarvey felt something scratchy in the neck of his shirt. He put a finger in and explored. He pulled out a card, though in the dimness he could not read it. Maybe Zoroaster’s card, though he didn’t remember keeping it. He stuck it into his pants pocket.

Puddler had been gone for ten minutes when Betsy spoke again: “Our turn. Let’s hurry. There’s the feel of rain, and I don’t like wading through knee-deep water down there.”

Jarvey fell into place right behind Betsy as they scuttled down into the drain. He carried the book against his chest, under his shirt, and squirmed at the touch of its cover. It was hard to believe that the book wasn’t alive, because the cover seemed to pulse, even to squirm, against his chest. He tried to ignore it. Betsy was in a hurry. They jogged through the dark, stooped over, breathing in the dank, stale air of the storm drains. They passed the grate where they usually emerged, made a turn, then another, until Jarvey felt completely lost. Still they hurried on, like a line of—well, of rats skittering through a tunnel.

Up on the surface the rain began. They couldn’t hear it, but soon they splashed through an ankle-deep rivulet of cold running water. Jarvey grimaced. The streets in the Toffs’ neighborhoods were always cleaned, but not in other places. Rotting garbage lay strewn in some streets until the rain washed it away. And when the water did sweep the filth away, it wound up here.

“Not much farther,” gasped Betsy. “But I want to scout ahead. You lot stays here.”

They milled uneasily in the rising water for a few minutes, and then they heard her voice again: “Right, come on. It’s pouring up there, and we’re going to get a dousing climbing out, but it can’t be helped. Jarvey, I’ll go first, and then you hand it to me.”

“I can manage it,” Jarvey said quickly.

“Suit yourself. Come on.”

The grate was just over their heads. A rush of water spilled through it and splashed the floor of the drain under it. Two of the boys made a stirrup of their hands and hoisted Betsy up. She slipped the iron drain cover aside, then climbed out through the falling water. She reached an arm down on the dry side. “Come on, grab hold and I’ll help you.”

Jarvey turned his back on the rushing water, grabbed Betsy’s outstretched hand, and felt the others boosting him as he kicked and hauled himself up. Betsy was strong, and she did more than her share. Jarvey tried to keep himself curled over the Grimoire, protecting it.

He climbed up into dim light. “Where are we?”

“Courtyard. Back behind us is where some servants lives. Quiet.”

When they were all up, Betsy led them to some protection from the spear-sharp rain, a carriage house. It had been left carelessly open, and they gratefully huddled inside, hearing the drumming of rain on its roof.

“Mill overseers live on this street,” Betsy whispered. “They ain’t so high-and-mighty as Toffs, but they ain’t our friends either. I know this family pretty well. They have a daughter my age, and I’ve even talked to her now and again. She thinks I’m the daughter of a chief tipper—”

Somebody giggled, and Betsy hissed, “Stop! Quiet, now.”

“Aw, Bets,” someone else said. “In this rain they couldn’t hear a brass band. We’re safe enough.”

Betsy ignored that. “We’ll stay here a bit, see if the rain eases off. It generally does by midnight. Then we’re not far from some places where we can hole up. Puddler and his bunch have gone to the safest snug, ’cause they’re the youngest. Charley’s takin’ the others to the butcheries—I know, I know, it ain’t the healthiest snug around, but Charley knows how to get ’em in and out safe. We’re going to break up, so that each of us is in a different place, but we’ll be close enough so we can get back together by night. All right?”

Jarvey heard a general, reluctant murmur of consent. His stomach felt fluttery. He hadn’t been on his own since that first horrible night, weeks ago. And though Charley had warned him that being with the others didn’t necessarily mean he was safe, he didn’t like the thought of being on his own in Lunnon, especially not in a place so close to the Toffs.

The pounding rain slackened gradually, and by midnight it had given way to a heavy, drifting drizzle, more of a choking fog than a real shower. They slunk out of their shelter and squelched along. Betsy sent one of the boys into an abandoned stable—“They sold their horse, and they ain’t bought another for over a year, so it should be safe if you climb up into the hayloft and keep quiet by day.” Another would hide in the attic of a small restaurant. “You can climb up onto the porch roof,” Betsy whispered to him. “Then you’ll find the ventilator cover’s loose. Be sure to pull it back after you. They never come up there, but there’s a lot of old pots and pans stacked about, so mind you don’t blunder into them. Stay quiet through the day and go out after dark.”

Then she led Jarvey for what felt like miles. “Saved the best for us,” she muttered. “’Cept it’s the most dangerous too. We’re going to stay in a right snooty place, we are. Close to the palace itself.”

“What?” Jarvey whispered.

“Look,” Betsy said wearily, “you were right about the palace. You don’t know how to use that book. I don’t know. The only one that does is old Nibs. Somethin’ in his house might hold the key, so we’ve got to go lookin’ for it. If we’re caught, we’ll be—I don’t know. Chopped up into pieces and stewed, maybe. But if we stay out dodgin’ tippers long enough, you’re going to be taken, and then what’s the odds?”

“How far is it?”

“Not far.”

They walked some more, and then Jarvey asked, “What is this place we’re going to?”

“Palace has servants, right?” Betsy whispered back. “Some of them, the la-di-dah ones, lives right in the palace, but most don’t, cleanin’ maids and that. Well, within a short walk of the palace is a kind of flats block—you know what that is, a flats block?”

“What we call an apartment house,” Jarvey said. “Yes, I know.”

“Right. Well, this one has about a dozen flats in it, for the women servants. Every flat has three girls in it. But it’s like most buildings—it has an attic, and the attic is empty. And we can stay there because servant girls is superstitious, and from time to time they hear a ghost up there.”

“What do you mean, a—”

“Ooooooooo,” moaned Betsy, her voice rising and falling.

“Oh.”

“Come on. Ain’t no way up to the attic from the outside, though you can climb out onto the roof from there and get away in a pinch. Got to go in through the building before first light, when one of ’em goes to the pump to fetch water.”

They crept through the night until at last they reached a two-storied house, dark and silent. Ahead of them, gas lights made ruddy wavering circles in the fog. “The palace gates,” Betsy whispered. “Guards there, but what with the weather and the dark, they’ll pay us no notice. Come with me.”

The stone house lay surrounded by hedges, and Betsy led the way into a narrow clear space between wall and hedge. The front door was at the top of a short flight of six stone steps, and Betsy and Jarvey crouched beside these for what seemed like hours, until Jarvey’s knees began to throb. The fog had just begun to turn a paler shade of gray when lights came on inside the house. A moment later, Jarvey heard the click of the front door being unlocked, and then two girls, each with a yoke over her neck from which dangled two big empty pails, came out, sniffing the morning air.

“Going to be a wet day,” one of them observed.

“We’ll have to hang the clothes inside, then,” the other returned.

Chatting, the two of them clanked off into the gloom, and as soon as they had gone, Betsy tugged at Jarvey’s sleeve. “Now.”

They climbed over the step rail and ducked inside. The house was as silent as could be. Betsy led Jarvey up a dim stairway, illuminated only by a low gas night-light at each landing. The last stretch of stairs ended at a trapdoor in the ceiling. Betsy shoved at it, and it creaked open. She climbed through it, beckoning Jarvey to follow.

He pulled himself through, and together they let the trapdoor drop down silently. Jarvey fought an urge to sneeze. The air in the attic drifted thick with dust. “Don’t move now,” Betsy said. “Get into a comfortable position and stay that way until all the maids leave for the palace.”

He stretched out, more or less, and soon dozed off. He didn’t know how long he slept, but when Betsy shook him awake again, he could see. Thin daylight filtered in through ventilators in each gable of the steep roof. It didn’t help much. Close to the trapdoor, a rampart of trunks and boxes stood, evidently hauled up to the attic in years past and then forgotten, for all of them wore furry coats of gray dust.

“They’re out,” Betsy said. “I think they’ve all gone. Sometimes one of them is sick and stays behind, and then you’ve got to be really quiet. Today, though, it sounds like they’ve all left for the palace. We’ll hole up behind the trunks and things. I’ll go down to their kitchens and slenk some food for us.”

“Okay,” agreed Jarvey. He stretched and then explored. If they had everything behind the trunks to themselves, they had most of the attic. It felt warm—warmer than the old Den in the alley, anyway—and seemed dry enough. Behind him, Betsy dropped through the trapdoor. Jarvey drew close enough to one of the big round ventilators to have a reasonable amount of daylight, and then he pulled out the Grimoire and studied its covers.

The way to find his parents, Zoroaster had said, lay in the Grimoire. He tugged at it, but it remained obstinately shut, as though the pages had been glued together. Jarvey took some minutes building up his nerve, then tapped the front cover with his finger and said, “Open!” in what he hoped was a commanding voice. Nothing happened. He took a deep breath and muttered, “I, Jarvis Midion, command you to open!”

The book seemed unimpressed.

Jarvey sighed and inspected the volume. The brass hinges gleamed dully against the pebbled, brownish red surface, and the brass catch could be flicked open easily enough. Still, regardless of what Zoroaster might have believed, the pages obstinately refused to open. Even for a Midion.

Clutching the book against his chest, his chin resting on the top edge, Jarvey thought about the weird moment when Siyamon Midion had given an order in a strange language. What had it been? Abracadabra, or something like that? Jarvey strained, but he could not quite bring back the strange syllables he had heard just before Zoroaster had barged in, yelling for him to beware the book. Jarvey could recall his own terror, the heart-stopping sensation of being turned inside out, of falling endlessly. He could see in his mind’s eye long, crooked streaks of red and blue lightning. He could remember hearing shrieks and moans from the book’s fluttering pages.

Not the words, though, not the spell that Siyamon had shouted just before the world had gone crazy. And if he could remember them, what then? He shuddered at the thought of the Grimoire opening once more, pulling him from Lunnon into some even worse place, if that were possible.

Zoroaster might have helped, but he had disappeared again, and Jarvey couldn’t just wait around for him. There was only one other alternative. If he wanted to learn something about the magic that controlled the book, he had to find his way into the palace.

The trapdoor opened and closed, interrupting Jarvey’s thoughts, and in a moment Betsy joined him, a look of triumph on her face. “Not too bad,” she announced. “They keep a larder of food here for night meals, for most of them eat in the palace kitchens by day. I took a bit from here and a bit from there, and no one’s likely to miss any of it. Cheese, biscuits, grapes, apples, even some chocolates. Help yourself.”

They began to munch on the food. Jarvey tilted his head. “You’re talking different,” he said.

She shrugged. “On the street you learns to talk street talk, cully. Away from the street, you can speak more properly if you wish.”

Jarvey didn’t say anything, but he seemed to hear Charley’s voice whispering inside his head: “Wonder what else she’s been hidin’ from you, mate.”

Impulsively, Jarvey said, “Tell me more about your mother.”

“Don’t know much. I haven’t seen her in ages, and I don’t think I can find her, at least as long as old Nibs runs this town. What you and I have to do is take it away from him.”

Jarvey shook his head. “Why did he make Lunnon in the first place?”

She laughed without really sounding amused. “I’ve had a lot of time to think about that. Well, for one thing, he’s old, really old. In the year 1848, he would have been about seventy. Now you say that in the real world, the world where he came from, a hundred and sixty years or so have gone by. So he’s two hundred and thirty, right? In real time, he’d be long dead by now. In book time, he stops aging. He stays the same as he was when he came into the book. So he made this place in order to live forever. And why did he make it with the Toffs and the rest of us? Why, cully, people like Tantalus Midion ain’t happy lest they have a boot on some poor unfortunate’s neck.”

She leaned a little closer. “Listen, here’s what I think. Tantalus couldn’t make all of Lunnon. That’s too big a magic even for him, even when he had the Grimoire. He could open the way to this place, but not create a city. So he found this world, saw it was the right proper sort of spot for what he wanted, and started in on his plan. He began to bring people here. First some of the Toffs, men who didn’t want to die and who took his way out of the real world.”

“Magicians like him?”

“No, I don’t think so. Least, nobody’s ever seen anyone but old Nibs do magic in Lunnon. See, his Toffs can’t do magic, but he can use ’em to drive the others. Then with the Toffs’ help, old Tantalus kidnapped laborers, and maybe their wives and children. People to build, see? Lumber mills and brick mills and things, and then houses and places to make clothes and cook food and so on. And the children of those first laborers were born, and instead of staying babies, they grew up and became the next generation of poor folk and workers, and they had to be servants and slave in the mills. And old Nibs and the Toffs, why, they lorded it over all. Nibs is king here. He made Lunnon the way he remembered the old world, but put himself on top of the heap, like.”

“But only the Toffs are happy. Everyone else—”

“Everyone else doesn’t matter,” she said flatly. “I doubt there’s more than a thousand or two thousand like my mother. Transports, I mean. Everyone else was born here, and for us book time is real time.”

Jarvey thought about that. “Look, I’m trying to find a way to open the Grimoire. But if I do, what happens?”

Betsy grinned. “Don’t know. But I think what may happen is that you’ll open the door back to your world from this side. If you do, then maybe we can send Nibs back to the real world, and he’d be stuck there, because he wouldn’t have the book to get back to Lunnon.”

Jarvey licked his lips. “Zoroaster seemed to think—he hinted that it might be the end of the world. The end of this world, anyway. Lunnon might disappear, everyone in it might die.”

She shrugged. “What’s the odds? Go on living like we do, like rats under their feet, or have it all over with and die quick and clean?” Her green eyes almost glowed in the faint light. “I’d sooner go quick than linger on in misery.”

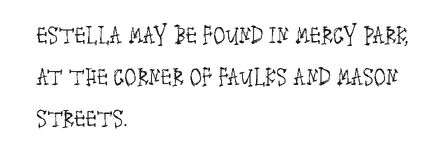

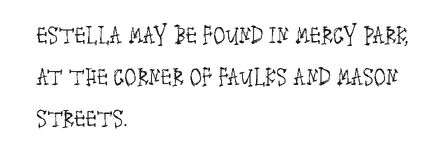

Something tickled Jarvey’s leg, like an insect walking over his skin, and when he reached down to brush it off, he found the card he had fished out of his collar and shoved in his pocket. It had worked its way almost out, and when he looked at it, he saw tiny, spidery handwriting:

“What’s that?” Bets asked.

Jarvey passed the card to her. “I don’t know. I thought this belonged to Zoroaster, but—what’s wrong?”

“Nothing.” Betsy crumpled the card. “Just rubbish. Look, you need to get some rest. It’s been a hard day.” She made her way to the far side of the attic, where she sat with her back against a wall and her knees drawn up. Something about her posture warned Jarvey not to question her about the message.

Jarvey stretched out on the floor and tried to get comfortable, still wondering about the Grimoire and what he might be able to do if he opened it. If he sent Tantalus back, would the old man wind up in his own time, or in the twenty-first century? What would happen to Jarvey and his parents? He shivered at the thought of being thrust into the remote past, lost, still separated from his mom and dad.

“I want to go home,” he whispered, so softly that not even Bets’s sharp ears could have heard the small, forlorn sound. “I just want to go home.”

Maybe Bets preferred a quick, clean end. Jarvey wanted life. Not only for himself, but also for his mother and his father.