LAND & PEOPLE

LAND & PEOPLE |

|

Bordered on the north and west by Switzerland and France, and to the northeast by Austria and Slovenia, Italy’s landmass extends south into the Mediterranean, between the Ligurian and Tyrrhenian seas in the west and the Adriatic and Ionian seas in the east. Italy is first and foremost a Mediterranean country and the Italians share characteristics with other Latin nations—spontaneity, and a relationship-based and not particularly time-conscious society. Of the three main islands off its coast, Sicily and Sardinia are Italian, while Corsica—birthplace of Napoleon Bonaparte—is French. The capital, Rome, lies more or less in the center.

Italy is shaped like a boot, reaching down from central southern Europe with its toe, Sicily, in the Mediterranean and its heel, the town of Brindisi, in the Ionian Sea. From top to toe it is about 1,000 miles (1,600 km) by the national expressway (autostrada) network. The Brenner Pass in the north is on the same latitude as Berne in Switzerland, whereas the toe of southern Sicily is on the same latitude as Tripoli in Libya. Only a quarter of the country is arable lowland, watered by rivers such as the Po, Adige, Arno, and Tiber. The whole of the northern frontier region is fringed by the Alps, including the jagged peaks of the Dolomites, while the Apennine Mountains run like a backbone down the peninsula from the Gulf of Genoa to the Straits of Messina, with snow-covered peaks until early summer.

Italy’s climate is Mediterranean, but northern Italy is on average four degrees cooler than the south because the country extends over ten degrees of latitude. The inhabitants of Milan, in the great northern plain of the River Po, endure winters as cold as Copenhagen in Denmark (40°F/5°C in January), whereas their summers are almost as hot as in Naples in the south (88°F/31°C in July)—but without the refreshing sea breezes. Turin, at the foot of the Alps, is even colder in winter (39°F/4°C in January) but has less torrid summers (75°F/24°C in July).

All the coastal areas are hot and dry in summer but subject also to violent thunderstorms, which can cause sudden flash floods. Inland cities such as Florence and Rome can be delightful early in the year (68°F/20°C in April), but unpleasantly heavy and sticky in July and August (88°F/31°C).

Spring and early summer and fall are the best times to visit, though in Easter week Italian town centers are full of tourists, and in April and May they are packed with crowds of Italian schoolchildren on excursions. September and early October, when hotel rates and plane fares are cheaper, are often especially beautiful with clear fresh sunny days at the time of the grape harvest. October and November, the months of the olive harvest, have the heaviest rainfall of the year, but the winter months can also be wet, so take a waterproof coat and a good comfortable pair of walking shoes. (Naples has a higher average annual rainfall than London!) This is the time for the operagoer, and the winter sports enthusiast, or to enjoy crowd-free shopping in Milan, Rome, or Venice. But before February is out, the pink almond is already blossoming in the South.

Italy’s population is about 61 million, in spite of having one of Europe’s lowest birth rates and the greatest gaps between births and deaths. The population has fallen 3.7 percent since 2009. The greatest decline, according to the Italian Statistics Office ISTAT is in the northeast and the islands.

Changes in the population are due to three factors; lower birth rates, greater emigration, and a longer-lived population. Italy now has one of the oldest populations in Europe, second only to Germany, and the level of population has been boosted by immigration. According to statistics, 4.9 million foreigners now have Italian citizenship.

One reason for this is smaller families as more and more women seek their own careers, even though women still make up only a relatively small percentage of the professional and technical workforce. While 88 percent of all Italian women have one child, over half decide not to have another. Interestingly, the life expectancy of Italian women has doubled in fifty years to an average age of eighty-two.

According to UN estimates, some 300,000 immigrant workers a year will be needed to maintain Italy’s workforce. There has been a steady stream of migrants from North Africa and the Far East, but the majority now come from central and southeastern Europe. Although Italy has made some attempts to curb immigration, these foreign workers are also regarded as “useful invaders.” For decades, Italy was a land of emigration (principally to the USA and Latin America, and later Australia). The presence of immigrants in Italy’s cities is a relatively new phenomenon and many Italians are still coming to terms with it.

A noted issue in recent Italian politics has been the influx of refugees from southeastern Europe and the war-torn areas of Syria, Libya, and the Sahel, many via Istanbul.

Stories of refugees crossing the Mediterranean in ageing hulks of boats, trafficked by criminals, often abandoned and left to drift toward the Italian shores maybe to be rescued by Italian coastguards, was one of the recurring tragedies in international news in 2014–15 and one which the inadequately resourced EU Mediterranean fleet could not successfully resolve.

The Italian navy said it could no longer resource the rescue operations at the level needed, and at the end of 2014 EU backers were also announcing cutbacks in their support.

Italy contains two mini-states, the Republic of San Marino and the Vatican. San Marino covers just 24 square miles (61 sq. km), and is the world’s oldest (and second smallest) republic, dating from the fourth century CE. The Vatican City, a tiny enclave in the heart of Rome, is the seat of the Pope, head of the Roman Catholic Church.

Measuring 109 acres (0.4 sq. km), less than a third of the size of Monaco, the Vatican is a sovereign state on the west bank of the Tiber. This tiny area is what remains of the Papal States, which were created by Pope Innocent II (1198–1216) by playing off rival candidates for the title of Holy Roman Emperor. Before their conquest by the Piedmontese in the 1860s, the Papal States stretched from the Tyrrhenian Sea in the west to the Adriatic in the east, and had a population of three million souls. Today the Vatican is the world’s smallest state, with an army of Swiss Guards (actually mainly Italians on temporary posting), and a population of about a thousand. Most of the workers in the Vatican City live outside and commute in every working day. As a state, it has all it needs: a post office, a railway station, a helipad, a TV and radio station broadcasting in forty-five languages, a bank, a hospital, refectories, drugstores, and gas stations.

CAPITAL |

|

Valle d’Aosta |

Aosta |

Piemonte (Piedmont) |

Torino (Turin) |

Lombardia (Lombardy) |

Milano (Milan) |

Trentino-Alto Adige |

Trento |

Veneto |

Venezia (Venice) |

Friuli-Venezia Giulia |

Trieste |

Liguria |

Genova (Genoa) |

Emilia-Romagna |

Bologna |

Toscana (Tuscany) |

Firenze (Florence) |

Umbria |

Perugia |

Marche |

Ancona |

Lazio |

Roma (Rome) |

Abruzzi |

L’Aquila |

Molise |

Campobasso |

Campania |

Napoli (Naples) |

Puglia |

Bari |

Basilicata |

Potenza |

Calabria |

Catanzaro |

Sicilia (Sicily) |

Palermo |

Sardegna (Sardinia) |

Cagliari |

The authority of the Vatican was established in 380 CE when the primacy of the Holy See—the jurisdiction of the Bishop of Rome—was officially recognized by the Western Church. As a result Rome is the “Eternal City” to 1.2 billion Roman Catholics worldwide. Paradoxically, in 1985 a Concordat was signed under which Catholicism ceased to be Italy’s state religion.

The glories of the Vatican City are its museum, which houses the Sistine Chapel and countless works of art, and St. Peter’s Basilica. This can seat a 60,000-member congregation and is 611 feet (186 meters) long, 462 feet (140 meters) wide, and 393 feet (120 meters) high. Built between 1506 and 1615, its magnificent dome and the square Greek-cross plan were designed by Michelangelo, who worked on it “for the love of God and piety”—in other words, without pay! St. Peter’s houses Michelangelo’s Pietà (the statue of the seated Virgin holding the limp body of the dead Christ), and Bernini’s bronze canopy (baldacchino) over the high altar.

At the head of the Vatican administration is the Pope, aided by his state secretariat under the Secretary of State. There are ten congregations, or departments, dealing with clerical matters, each headed by a cardinal. The most important is the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, formerly the Inquisition. All Catholic bishops are enjoined to go to Rome at least once every five years to see the Pope “at the threshold of the Apostles.”

The leading sacred establishment in the Vatican is the Curia, or College of Cardinals, which comprises 226 members, of which 124 are entitled to elect the new Pope. After the death of a Pope the electors meet in conclave and are locked into the Sistine Chapel until a new Pope is elected. After each vote, the ballots are burned and black smoke drifts up from the Sistine Chapel chimney. When a new Pope has been elected, a chemical is added to the ballot papers to turn the smoke white, and the new Pope in his papal regalia appears to the public in the piazza. He is crowned the following day in St. Peters.

Rome is Italy’s capital and the seat of government and has a population of 3.5 million. Though situated in the center of Italy, Rome is regarded as a “Southern” city in its style and general outlook.

With a population of 2.9 million and situated in the northern region of Lombardy, Milan is Italy’s “New York.” Sometimes described by its citizens as the real capital, Milan is the industrial center of Italy and home to two of its most famous football teams, Inter Milan and AC Milan. It is also the seat of Italy’s Borsa, or Stock Exchange.

One of the busiest ports in Italy and the “capital” of the South, Naples has a population of over two million. It is the jumping off point for visits to the towns of Pompeii and Herculaneum, preserved by the lava that buried them after the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE, and for visits to the islands of Capri and Ischia.

The capital of Piedmont, Turin (pop. 1.6 million) is the gateway to the Italian Alps and a major industrial center and transportation junction.

Founded by the Phoenicians in the eighth century BC, Palermo (pop. 872,000) is the capital and chief seaport of Sicily.

This industrial city and ancient university town (pop. 384,000) is the capital of Emilia-Romagna. It is famous for the quality of its food and is also a transportation center and agricultural market.

Genoa (pop. 607,000), the capital of Liguria in the northwest, is Italy’s largest port and a leading industrial and commercial center.

The capital of Tuscany, Florence (pop. 374,000) is famous for its architectural and artistic treasures, dating from its heyday as the leading architectural city of the Italian Renaissance under the Medici. Today it is also a fashion center and a major commercial, transportation, and industrial hub.

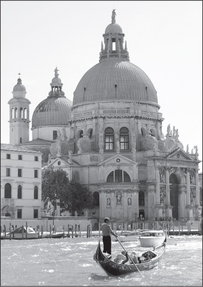

Capital of the Veneto region, Venice (pop. 270,000, including the mainland) is the other great Renaissance center. The old city is built on piles on islands in a saltwater lagoon, and is famous for its canals and bridges. It is both a leading cultural and architectural attraction and a major port.

Italy is renowned for its magnificent art treasures and breathtaking scenery. Two of its greatest admirers were the nineteenth-century Romantic poets Percy Bysshe Shelley and Lord Byron, both of whom lived there. Shelley, who was drowned in a storm in a small boat off the coast, near La Spezia, described Italy as “Thou paradise of exiles” (Julian and Maddolo, 1819), and Byron in a letter to Annabella Milbanke on April 28, 1814, wrote “Italy is my magnet.” Almost a century later, Henry James wrote to Edith Wharton, “How incomparably the old coquine of an Italy is the most beautiful country in the world—of a beauty (and an interest and complexity of beauty) so far beyond any other that none other is worth talking about.”

Interestingly, Italians, from the late medieval poets Boccaccio and Dante onward, describe their country very differently. Over the centuries Italy has been depicted as a whore, a fallen woman, or even a brothel. Many of Italy’s contemporary problems derive from its history as a land of separate, warring city-states, later ruled by other European powers. Italy was not unified until 1861 and in a sense still has the feeling of a “young” country, despite its antiquity.

In the Bronze Age, from about 2000 BCE, Italy was settled by Indo-European Italic tribes from the Danube basin. The first indigenous sophisticated civilization was that of the Etruscans, which developed in the city-states of Tuscany. In 650 BCE Etruscan civilization expanded into central and northern Italy, setting an early example of urban living. The Etruscans controlled the seas on either side of the peninsula, and for a while provided the ruling dynasties in neighboring Latium, the lowlands in the central part of Italy’s western coast. Etruscan ambitions were eventually checked by the Greeks at Cumae near Naples in 524 BCE, and the Etruscan navy was defeated by the Greeks in a sea battle off Cumae in 474 BCE.

At about this time, Greek colonies in Southern Italy were introducing the olive, the vine, and the written alphabet. Greek civilization would, of course, have a major influence on the future Roman Empire.

During the fourth and third centuries BCE Rome, the leading city-state of Latium, rose to prominence and united the Italian peninsula under its rule. Legend has it that Rome was founded by Romulus and Remus, twin sons of the god Mars and the King of Alba Longa’s daughter. Left to die near the River Tiber, the abandoned babes were suckled by a she-wolf until they were discovered by a shepherd, who brought them up. Eventually Romulus founded Rome in 753 BCE on the Palatine Hill above the banks of the Tiber where the wolf had rescued them. He was to become the first in a line of seven kings.

Following the expulsion of its last Etruscan king, Rome became a republic in 510 BCE. Its political dominance was underpinned by its remarkably stable constitutional development, and eventually all of Italy gained full Roman citizenship. The defeat of foreign enemies and rivals led first to the establishment of protectorates and then the outright annexation of territories beyond Italy.

The Republic’s victorious march across the known world continued despite political upheavals and civil war, culminating in the murder of Julius Caesar in 44 BCE and the establishment of the Roman Empire under Augustus and his successors. Thereafter Rome flourished. Augustus famously “found Rome in brick and left it in marble.” The city was burned down in 64 CE during the reign of the Emperor Nero, who, to deflect the blame, initiated a period of persecutions of Christians. It is around this time that Saints Peter and Paul were executed. Peter was crucified upside down, whereas Paul—a Roman citizen by birth—was beheaded.

The Roman Empire lasted until the fifth century CE, and at its peak extended from Britain in the west to Mesopotamia and the Caspian Sea in the east. The Mediterranean effectively became an inland lake—mare nostrum, “our sea.” The civilization of ancient Rome and Italy took root and had a profound influence on the development of the whole of Western Europe through the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, and beyond—in art and architecture, literature, law, and engineering, and through the international use of its language, Latin, by scholars and at the great courts of Europe.

In 330 CE Constantine, the first Christian emperor, moved his capital to Byzantium (renamed Constantinople—modern-day Istanbul), and Rome declined in importance. In 395 the Empire was divided into eastern and western parts, each ruled by its own emperor. There was continuous pressure along the borders as barbarian tribes probed the overstretched imperial defenses. In 410 Rome was sacked by Visigoths from Thrace, led by Alaric. Further incursions into Italy were made by the Huns under Attila in 452, and the Vandals who sacked Rome in 455. In 476 the last western Emperor, Romulus Augustus, was deposed, and in 568 Italy was invaded by the Lombards, who occupied Lombardy and central Italy.

With the collapse of the Roman Empire in the west, the Church in Rome became the sole heir and transmitter of imperial culture and legitimacy, and the power of the papacy grew. Pope Gregory I (590–604) built four of the city’s basilicas and also sent missionaries to convert pagans to Christianity (including St. Augustine to Britain). On Christmas Day 800, at a ceremony in Rome, Pope Leo III (795–816) crowned the champion of Christendom, the Frankish king Charlemagne, Emperor of the Romans, and Italy was briefly united with Germany in a new Christian Roman Empire. From then until 1250, relations between the papacy and the Holy Roman Empire, at first friendly but later hostile, were the main issue in Italian history.

In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries Western Christendom’s spiritual and temporal powers, the papacy and the Holy Roman Empire, competed for supremacy. During this struggle the Italian cities seized the opportunity to become self-governing republics. Supported by the papacy, the Northern cities formed the Lombard League to resist the Emperors’ claims of sovereignty. Papal power and influence reached their peak under Pope Innocent III (1198–1216).

Italy became a jigsaw of kingdoms, duchies, and city-states running from the Alps to Sicily. Centuries of war and trade barriers fanned animosity between neighboring Italians and reinforced local loyalties. With the exception of the territory of Rome, ruled by the Pope, most of these states succumbed to foreign rule. Each preserved its own distinct government and customs and vernacular. Italian history was marked less by political achievements than by achievements in the human sphere. The great cities and medieval centers of learning were founded in this period—the University of Bologna, founded in the twelfth century, is Europe’s oldest.

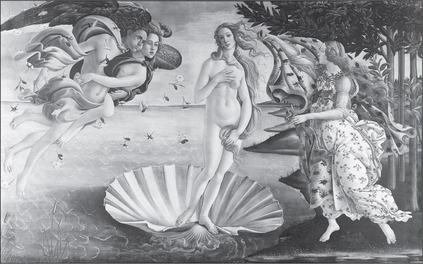

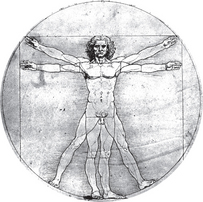

The fourteenth century saw the beginnings of the Italian Renaissance, the great cultural explosion that found sublime expression in learning and the arts. In the move from a religious to a more secular worldview, Humanism—the “new learning” of the age—rediscovered the civilization of classical antiquity; it explored the physical universe and placed the individual at its center. Boccaccio and Petrarch wrote major works in Italian rather than Latin. In painting and sculpture, the quest for knowledge led to greater naturalism and interest in anatomy and perspective, recorded in the treatises of the artist-philosopher Leon Battista Alberti.

During this period the arts were sponsored by Italy’s wealthy ruling families such as the Medici in Florence, the Sforzas in Milan, and the Borgias in Rome. This was the age of the “universal man”—polymaths and artistic geniuses such as Leonardo da Vinci, whose studies included painting, architecture, science, and engineering, and Michelangelo, who was not only a sculptor and painter, but also an architect and a poet. Other great artists were Raphael and Titian. Architects such as Brunelleschi and Bramante studied the buildings of ancient Rome to achieve balance, clarity, and proportion in their works. Andrea Palladio adapted the principles of classical architecture to the requirements of the age, creating the Palladian style.

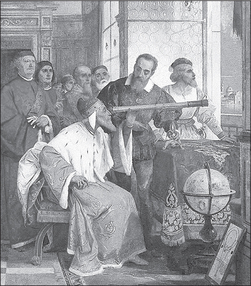

Andreas Vesalius, who made dissection of the human body an essential part of medical studies, taught anatomy at Italian universities. The composer Giovanni Palestrina was the master of Renaissance counterpoint, at a time when Italy was the source culture of European music. Galileo Galilei produced seminal work in physics and astronomy before being arrested by the Inquisition in 1616 and obliged to recant his advocacy of the Copernican view of the solar system in 1633.

The invention of printing and the geographical voyages of discovery gave further impetus to the Renaissance spirit of inquiry and scepticism. In its bid to halt the spread of Protestantism and heterodoxy, however, the Counter-Reformation almost extinguished intellectual freedom in sixteenth-century Italy.

In the fifteenth century most of Italy was ruled by five rival states—the city-republics of Milan, Florence, and Venice in the north; the Papal Sates in the center; and the southern Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (Sicily and Naples having been united in 1442). Their wars and rivalries laid them open to invasions from France and Spain. In 1494 Charles VIII of France invaded Italy to claim the Neapolitan crown. He was forced to withdraw by a coalition of Milan, Venice, Spain, and the Holy Roman Empire.

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries Italy became an arena for the dynastic struggles of the ruling families of France, Austria, and Spain. After the defeat of France by Spain at Pavia, the Pope hastily put together an alliance against the Spaniards. The Habsburg Emperor Charles V defeated him and in 1527 his German mercenaries sacked Rome and stabled their horses in the Vatican. For some modern historians this act symbolizes the end of the Renaissance in Italy.

Spain was the new world power in the sixteenth century, and the Spanish Habsburgs dominated Italy. Charles V, who was both King of Spain and Archduke of Austria, ruled Naples and Sicily. In the seventeenth century Italy was effectively part of the Spanish Empire, and went into economic and cultural decline. After the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, Austria replaced Spain as the dominant power, though the Kingdom of Naples came under Spanish Bourbon rule in 1735, leaving a profound influence on the culture of the South.

The old order was swept aside by the French revolutionary wars. In the years 1796–1814 Napoleon Bonaparte conquered Italy, setting up satellite states and introducing the principles of the French Revolution. At first he divided Italy into a number of puppet republics. Later, after his rise to absolute power in France, he gave the former Kingdom of the Two Sicilies to his brother Joseph, who became King of Naples. (This later passed to his brother-in-law Joachim Murat.) The Northern territories of Milan and Lombardy were incorporated into a new Kingdom of Italy, with Napoleon as King and his stepson Eugène Beauharnais ruling as Viceroy.

Italians under direct French rule were subject to the jurisdiction of the Code Napoleon, and became accustomed to a modern, centralized state and an individualistic society. In the Kingdom of Naples feudal privileges were abolished, and ideas of democracy and social equality were implanted. So although the period of French rule in Italy was short-lived, its legacy was a taste for political liberty and social equality, and a new-found sense of national patriotism.

In creating the Kingdom of Italy, Napoleon brought together for the first time most of the independent city-states in the northern and central parts of the peninsula, and stimulated the desire for a united Italy. At the same time, in the South there arose the revolutionary secret society of the Carbonari (“Charcoal-burners”), which aimed to free Italy from foreign control and secure constitutional government.

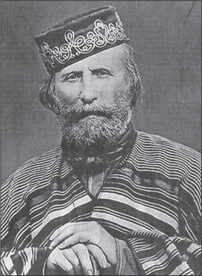

After Napoleon’s fall in 1815, the victorious Allies sought to restore the balance of power in Europe. Italy was again divided between Austria (Lombardy-Venetia), the Pope, the kingdoms of Sardinia and Naples, and four smaller duchies. However, the genie was out of the bottle. Nationalist and democratic ideals remained alive and found expression in the movement for Italian unity and independence called the Risorgimento (“Resurrection”). In 1831 the utopian radical Giuseppe Mazzini founded a movement called “Young Italy,” which campaigned widely for a unified republic. His most celebrated disciple was the flamboyant Giuseppe Garibaldi, who had started his long revolutionary career in South America. The chief architect of the Risorgimento, however, was Count Camillo Cavour, the liberal Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Sardinia.

The repressive regimes imposed on Italy inspired revolts in Naples and Piedmont in 1820–21, in the Papal States, Parma, and Modena in 1831, and throughout the peninsula in 1848–49. These were suppressed everywhere except in the constitutional monarchy of Sardinia, which became the champion of Italian nationalism. Cavour’s patient and skillful diplomacy won over British and French support for the struggle against absolutism. With the help of Napoleon III, Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia expelled the Austrians from Lombardy in 1859. The following year, Garibaldi and his army of 1,000 volunteers (known as “I Mille,” the Thousand in Italian, or the Red Shirts) landed in Sicily. Welcomed as liberators by the people, they swept aside the despotic Bourbon dynasty and made their way north up the peninsula.

Victor Emmanuel then entered the Papal States and the two victorious armies met at Naples, where Garibaldi handed over the command of his troops to his monarch. On March 17, 1861, Victor Emmanuel was proclaimed King of Italy at Turin. Venice and part of Venetia were secured by another war with Austria in 1866, and in 1870 Italian forces occupied Rome, in defiance of the Pope, thus completing the unification of Italy. The spiritual autonomy of the Pope was recognized by the Law of Guarantees, which also gave him the status of a reigning monarch over a certain number of buildings in Rome. The Vatican became a self-governing state within Italy.

With the passing of the heroes of the Risorgimento, the national government in Rome became associated with corruption and inefficiency. A sense that Italy’s unity had been made possible largely by its enemy’s enemies (France and Prussia) and real economic hardship led to demoralization and serious unrest. There were bread riots in Milan in 1898, followed by crackdowns on socialist movements. Against this backdrop, in 1900 King Umberto I was assassinated by an anarchist.

Italy now entered the arena of European power politics and started to entertain colonial ambitions. Thwarted by France in Tunis, Italy joined Germany and Austria in the Triple Alliance in 1882 and occupied Eritrea, making it a colony in 1889. An attempt to seize Abyssinia (Ethiopia) was decisively defeated at Adowa in 1896. However, war with Turkey in 1911–12 brought Libya and the Dodecanese islands in the Aegean, and dreams of the rebirth of a glorious overseas Roman Empire. On the outbreak of the First World War, Italy denounced the Triple Alliance and remained neutral, but in 1915 entered on the side of the Allies. The treaties of 1919, however, awarded Italy far less than it demanded—Trieste, the Trentino, and South Tyrol, but, importantly, very little in the colonial sphere. This humiliation would rankle for years to come.

The postwar period in Italy saw intense political and social unrest, which the universally despised governments were too weak to subdue. Patriotic disappointment with the outcome of the war was swelled by the existence of large numbers of ex-servicemen. In 1919 the nationalist poet and aviator Gabriele D’Annunzio led an unofficial army to seize the Croatian port of Fiume, awarded to Yugoslavia under the Treaty of Versailles. Although the coup collapsed after three months, it proved to be a dress rehearsal for the Fascist takeover four years later.

In the following years inflation, unemployment, riots, and crime were rife. Workers’ soviets were set up in factories. Socialists and Communists marched through the streets. Against this background, the “clean sweep” offered by Benito Mussolini’s right-wing populist Fascist movement appealed widely to the threatened middle classes, industrialists, and landowners, and to patriots of all classes. Its insignia was the ancient Roman symbol of authority, the fasces—an ax surrounded by rods tightly bound together for strength and security. Electoral gains in 1921 led to growing arrogance and violence, and squads of armed Fascists attacked and terrorized their enemies in the big towns.

In October 1922 the fiery young Mussolini addressed thousands of black-shirted followers at a rally in Naples demanding the handover of government; the crowd responded with chants of “Roma, Roma, Roma.” The Fascist militias mobilized. Luigi Facta, the last constitutional Prime Minister, resigned, and thousands of Blackshirts, or “Camicie Nere,” marched on Rome unopposed. King Victor Emmanuel III appointed Mussolini Prime Minister, and Italy entered a dangerous new era.

Mussolini moved quickly to secure the loyalty of the army. Critically, he reconciled the Italian state with the estranged Vatican, signing a solemn Concordat with the Pope in 1929 that conferred authority on his government. Although technically still a constitutional monarchy, Italy was now a dictatorship. The Fascist regime brutally destroyed all opposition, and exerted almost complete control over every facet of Italian life. In the early years, despite the suppression of individual liberties, it won wide acceptance by improving the administration, stabilizing the economy, improving workers’ conditions, and inaugurating a program of public works. Italy’s man of destiny, il Duce (“the Leader”), was idolized and came to embody the corporate state. There are obvious parallels with Adolf Hitler’s regime in Germany. Unlike the Nazis, however, Fascist doctrine did not include a theory of racial purity. Anti-Semitic measures were introduced only in 1938, probably under German pressure, and were never followed through in anything like the German manner.

Mussolini saw himself as heir to the Roman emperors, and aggressively set about building an empire. The well-equipped Italian army sent to conquer Ethiopia in 1935–36 used poison gas and bombed Red Cross hospitals. When threatened with sanctions, Italy joined Nazi Germany in the Axis alliance of 1936. In April 1939 Italy invaded Albania, whose king fled, after which Victor Emmanuel was proclaimed King of Italy and Albania, and Emperor of Ethiopia. Naturally supportive of fellow dictators, Mussolini intervened on the side of General Franco’s nationalist forces in the Spanish Civil War (1936–39), and entered the Second World War as an ally of Germany.

The war did not go well for Italy. Defeats in North Africa and Greece, the Allied invasion of Sicily, and discontent at home destroyed Mussolini’s prestige. He was forced to resign by his own Fascist Council in 1943. The new Italian government under Marshal Badoglio surrendered to the Allies and declared war on Germany. Rescued by German parachutists, Mussolini established a breakaway government in northern Italy. The Germans occupied northern and central Italy, and until its final liberation in 1945 the country was a battlefield. Mussolini and his mistress, Clara Petacci, were captured by Italian partisans at Lake Como while trying to flee the country, and shot. Their bodies were hung upside down in a public square in Milan.

In 1946 Victor Emmanuel abdicated in favor of his son, Umberto II, who reigned for thirty-four days. In a referendum in June, Italians voted (by 12 million to 10 million) to abolish the monarchy, and Italy became a republic. It was stripped of its colonies in 1947. A new constitution came into force the following year, and the Christian Democrats emerged as the party of government.

The new monarch abdicated and, with all members of the house of Savoy, was forbidden to reenter the country. (In May 2003 the Senate voted by 235 to 19 to allow the royal family, the Savoia, to return to Italy.)

In attempting to weld the peninsula’s separate entities into a single unified kingdom, Italy’s early leaders had created a highly bureaucratic state that was tailor-made for Mussolini to manipulate fifty years later. This overcentralized system, run from Rome, survived the downfall of Fascism and the end of the discredited monarchy, but it landed the fledgling republic with a huge and costly bureaucracy and antiquated mechanisms for decision-making.

For most of the second half of the twentieth century, Italy was governed by an increasingly corrupt Christian Democrat–Liberal–Socialist coalition. Endless power struggles within the coalition caused governments to collapse and reconstitute themselves with notorious regularity, but the regime was assumed to be a fixture. Since it was a powerful source of patronage, its excesses remained unchecked until the early 1990s, when scandalous revelations of graft at all levels of politics and big business caused the Christian Democrat majority to wither away overnight. For the Italians, this was almost as momentous an event as the end of the Soviet Empire.

The darkest period in Italy’s postwar history, echoes of which can be heard even today, were the anni di piombo, or “Years of Lead.” During what one Italian journalist described as a low-intensity civil war in the 1960s, there were 15,000 terrorist attacks in which 491 Italians were killed, including leading politicians such as the Christian Democrat leader Aldo Moro. The anni di piombo lasted right up to the early 1980s and spawned a number of notorious groups such as the Red Brigades (Brigate Rosse), and atrocities by left-wing activists such as the explosion in Piazza Fontana in Milan in 1969. In this period Italy was plagued by crime from both left and right.

The Mafia, the traditional source of organized crime in Italy, originating in Sicily, controlled local politicians and businesses, often with considerable internal violence, and assassinated judges and politicians who resisted them. (In Sicily the Mafia is known as the Cosa Nostra; its Neapolitan counterpart is the Camorra.)

The 1990s saw the Mani Pulite, or “Clean Hands,” anticorruption campaign to clean up public life. Although there is a degree of cynicism about the results, the campaign marked a break with the violent extremist politics of the ’60s and ’70s and the emergence of a more mainstream government. After major electoral reforms, the 1996 elections were a fight between the old-established opposition parties and a cluster of newcomers, the ex-Communists and their allies versus a hastily assembled right-wing coalition consisting of the reformed neo-Fascists, a rapidly growing Northern separatist party (the Lega Nord, also known just as the Lega), and Forza Italia, led by the media tycoon (and one of the world’s richest men) Silvio Berlusconi. For fifty years after the Second World War, Italy had succeeded in keeping its two extremes, Fascism and Communism, out of national government. The Communists were the second-largest and best-organized party in Italy but were excluded due to the Cold War fear of Marxism. The neo-Fascists were still seen as too closely associated with memories of the rule of Mussolini.

Now the old antagonists have changed their images and today both right and left are trying to present themselves as “mainstream.” The ex-Communists (rebaptized Partito Democratico della Sinistra, or PDS) were the leading players in the center-left coalition that led the country after 1996 and presided over the stringent fiscal reforms that enabled Italy to join the European Monetary Union in January 1999.

In the 2001 elections, Silvio Berlusconi, head of Mediaset and a range of other international and national business interests, and leader of the Forza Italia coalition in the Italian Parliament, became prime minister. The following year, Italy held the presidency of the European Union.

Berlusconi was the longest serving prime minister in Italian history but stood down in 2011 following his failure to achieve an outright majority in Parliament and on a budget vote and faced with an increasing number of scandals in his own private life.

Faced with a leaderless coalition, the President appointed a former economics professor, Mario Monti, as head of a “government of technocrats” with the remit to initiate reforms aimed at putting the faltering Italian economy back on its feet. Monti’s style was completely the opposite of Berlusconi’s. He introduced a series of austerity measures aimed at rebalancing the Italian economy, notably cutting politicians’ “perks,” reviewing the early and generous state employees’ pension scheme, and investigating and attacking tax evasion.

Monti’s government coalition fell after two years, in 2013, following the withdrawal of Berlusconi’s Forza Italia party. The Chamber of Deputies appointed a new prime minister, Enrico Letta in 2013, replacing him with Matteo Renzi in 2015. Since 2011, therefore Italy has had three prime ministers but no general election.

Under its constitution, Italy is a multiparty republic with an elected president as Head of State and a prime minister as Head of Government. There are two legislative bodies, a 325-seat Senate and a 633-seat Chamber of Deputies. Elections are held every five years. The prime minister is the leader of the party or coalition that wins the election. The country is divided administratively into twenty regions that reflect to a considerable degree its traditional regional customs and character.

Politics in Italy is confrontational, and at street level has sometimes been murderous, but in the end it is always about the art of accommodation.

Some Italian cities such as Bologna are famous for their left-wing politics, and the large and prosperous center-north “red” regions of Tuscany, Emilia-Romagna, and Marche have a long Communist tradition. Over the years, however, Italian politics has become more centrist, and the country is settling into an alternation of center-left and center-right coalitions.

Apart from competing ideologies, when two strong personalities within a political party clash, the loser often starts another party, which then becomes part of one of the major coalitions.

Today in Italian politics, television is king and the center-right bloc is still dominated by Silvio Berlusconi, whose Mediaset conglomerate owns half of Italy’s TV and publishing industry and a top football team, AC Milan. Despite (or perhaps because of) extensive charges of corruption and tax scams, this self-made billionaire, calling for tax cuts and deregulation, is the hero of many of Italy’s small businessmen and entrepreneurs, not to mention soccer fans and TV addicts.

Fifty years ago, Italy was a largely agrarian society. It is now the eighth-biggest world economy by GDP according to the World Bank (2013 figures). Even today, though, it is characterized by great disparities of income. Pockets of wealth and industry, such as Milan, are in marked contrast to areas with a far lower standard of living, particularly in the South (known as the Mezzogiorno), where patron/client relationships are still common. Lombardy alone accounts for 20 percent of Italy’s GDP.

Although visited for its historic art treasures, Italy strikes the visitor as a modern nation in a continuing state of evolution. It is a relatively young nation, too. This is often reflected in a “get rich quick” mentality of unrestrained commercialism. Many areas of natural beauty have been ruined by indiscriminate property development, particularly along the coasts.

Italian business life is riven with contradictions. It is dominated by small enterprises with small staff, driven by the wish to avoid taxation and labor laws. But it is also led by international companies of great drive, flair, and ingenuity. As former editor of the Economist magazine, Bill Emmott, points out in Good Italy, Bad Italy, Italian companies do well when they internationalize. Italy leads the world in fashion, automobiles, food, and luxury goods, with brands such as Prada, Ferrari, and Nutella, whose founder and president Michele Ferrero, Italy’s richest man, died in 2015 at the age of eighty-nine.