chapter six

|

chapter six |

One of the great pleasures of Italy is eating and drinking. Each region has its individual cooking style and ingredients. In the north black pepper, butter, and rice are the staples. In the south it’s hot red pepper, olive oil, and pasta. In Piedmont scented truffle may be grated over your risotto, Liguria has a pasta sauce of crushed basil and pine nuts called pesto, in Tuscany you may eat fresh-caught hare and tomato, or wild-boar sausages, and in Sicily you will be offered the most delicious sardines. Many of these ingredients will have been prepared that day, bought fresh from the market.

Italy’s rich diversity and localism explains why there are over two thousand names for the huge variety of pasta shapes, and more wine labels—at least four thousand—than anywhere else in the world. Italy has many food festivals, called sagre, where local food is on display for tasting. Wine and truffle festivals are very popular. The Italian state tourist office, ENIT, publishes a booklet on the local festivals called An Italian Year.

In Italy breakfast (prima colazione) is normally around 8:00 a.m. and consists of biscuits or croissants, accompanied by strong coffee or perhaps tea. The main meal of the day is often lunch (pranzo), which starts anywhere between 1:00 and 2:00 p.m. and may last up to three hours (depending on the region), although office workers will usually eat and leave faster. If a heavy lunch has been eaten, the evening meal may consist of a light snack.

Dinner (cena) is usually around 8:00 p.m., but may be as late as 10:00 p.m. If the breadwinner cannot get back for lunch, dinner becomes the main meal. Children tend to stay up late, with no fixed bedtimes. Bread without butter is served and there is usually wine and water. When the family has guests, the head of the household pours the first round of wine and may propose a toast (brindisi) and then everyone serves themselves. “Cheers” in Italian is “Salute.”

A full-scale Italian meal is substantial, and so varied that it bears out the adage, l’appetito vien mangiando (the appetite grows with eating). Two main courses are preceded by a starter and followed by cheese, a dessert, and/or fruit. The starter, or antipasto, is often a selection of cold meats and marinated vegetables. Parma ham and melon are popular antipasti.

The first main dish, the primo, is usually pasta or risotto or perhaps a soup (minestra). Minestrone is a vegetable soup. The second main course, or secondo, will be meat or fish plus a cooked vegetable, often served separately as a side dish (contorno). The contorni (including potatoes) often follow the second dish as they are seen as palette cleansers rather than as an accompaniment to the meat or fish. Pasta is almost never eaten as a meal in itself, except for lasagne, and if you feel a whole portion of pasta as a first course is too much for you, it is acceptable to ask for a mezza porzione (half portion).

This may be followed by cheese and fruit, then dessert (dolce) and coffee. It is absolutely normal for Italians to drink wine with their meal, even in working hours. Tap water (acqua semplice) is free, but most Italians will ask for mineral water (acqua minerale), either sparkling (gassata) or still (non-gassata).

The bill (conto) will include Value Added Tax (IVA in Italian), and either a cover charge for pane e coperto (“bread and cover”) or a service charge (servizio) of around 12 percent. This does not go to your waiter so you may wish to add an extra few euros for him or her. Because of the prevalence of tax evasion in Italy, all shops, restaurants, and bars are required by law to issue customers with a scontrino (receipt). If they do not do so, they can be fined heavily.

Tipping is entirely at your discretion. Many restaurants have a service charge. The Italians are not generous tippers. If tipping for good service, they generally round up the bill to the nearest euro. A small gratuity is normally left for hotel porters and doormen and also chambermaids. Taxi fares may be rounded up, and if you buy a drink at the bar a small coin for the barman is often left along with the tab for your drink.

A TIME TO RELAX

No one is in a hurry when eating out in Italy. The interval between the secondo piatto and the cheese and fruit, followed by dessert and coffee, is the time for leisurely conversation and may easily add an hour to your meal.

Italians eat out a great deal and there is a wide range of establishments, all clearly identified. A ristorante (restaurant) is usually the most expensive option. A trattoria is a small local restaurant, usually family-run and mid-priced, offering a limited menu, but sometimes with excellent food. A taverna or osteria is simpler and less pretentious. However, always check the menu first as the type of restaurant isn’t always an indication of price.

Italians tend not to frequent burger joints, unless they have children. A pizzeria with a wood-burning stove is very popular, as is a gelateria, or ice-cream parlor. For quick meals, a rosticceria does spit-roasted meats and precooked chicken dishes. A tavola calda is a modest hot food bar. An enoteca (wine shop) may serve basic meals to accompany the usually excellent wines. Look for signs saying “Cucina casalinga”: this means the food is home-cooked, simple, unfussy, but satisfying. Avoid the menu turistico or menu a prezzo fisso (set-price meal) unless you want to eat quickly and cheaply, as the standard is often poor.

In Italy it is common to drink an aperitivo (aperitif) before meals. This may be a light white wine such as a Verdicchio or a Prosecco. Or you may be offered a spumante (sparkling wine). White and red wine (vino bianco and vino rosso) will be served during the meal. Wine can be ordered by the carafe (caraffa), quarter-liter (quartino), half-liter (mezzo litro), or liter (litro). Most Italians opt for the house wine (vino della casa), usually red. The meal may be followed by a digestivo (digestive), such as a cognac, a grappa (Italian brandy), or an amaro (a vermouth-type liqueur).

Like many Latins, Italians are not heavy drinkers and prefer to drink with food. Monsignor Della Casa in the Galateo, a manual of etiquette published in 1555, writes, “I thank God that for all the many other plagues that have come to us from beyond the Alps, this most pernicious custom of making game of drunkenness, and even admiring it, has not reached as far as this.”

If you are in a hurry and just want a quick coffee, or a refreshing drink, go into a bar and drink standing up at the counter (al banco). It is up to three times cheaper than sitting at a table inside or out on the terrace. Why? Because when you sit down, you have paid not just for a drink but for a “pitch” where you can talk, write, read, or watch the world go by. There will be no pressure to move on, although the waiter will ask if he/she can get you another drink.

Although Italian alcohol consumption is among the highest in Europe, it is spread evenly across the population and most people probably drink little more than a couple of glasses of wine a day. The idea of drinking to get drunk is foreign to the Italians. They may have a glass of grappa with their morning coffee, but alcohol is really seen as an accompaniment to food.

Although Italy is famous for its wines, beer is also popular. Moretti, Frost, and Peroni are popular local brands, served alla spina (draught), piccola (20 cl), media (40 cl), and grande (66 cl). For soft drinks, try granita, an iced summer drink made with lemon, orange, mint, strawberry, or coffee.

Few people in Britain or North America need educating about Italian coffee culture. Listed below are the most frequently ordered types. (Note that if you ask for un caffè, this means a small black espresso.)

If you want a decaffeinated coffee, ask for un decaffeinato or un caffè Hag. This isn’t drunk much in Italy. If you ask for tea, you will be brought hot water with a tea bag. By law, Italian bars and cafés must serve you a glass of water free of charge regardless of whether you buy anything.

Coffee |

Espresso: small strong black coffee (doppio espresso is double-size). |

Caffè lungo: small and black, but weaker than espresso. |

Caffè corretto: black with a shot of grappa (or some other liqueur). |

Caffè macchiato: black with a dash of milk. |

Caffelatte: a large coffee with lots of milk. |

Cappuccino: coffee with a thick layer of frothy milk and a scattering of chocolate on top (only drunk by Italians with breakfast and up to mid-morning). |

Italy is an extremely fashion-conscious culture, and Italian women, in particular, expect to spend a large percentage of their disposable income on clothes and accessories. You are how you dress, and clothes are a badge of success. Women wear quiet, well-cut, expensive and elegant clothes, and men’s ties and suits should also be fashionable and well-tailored. Even casual clothes are smart and chic. Remember that Italy, especially Milan, is a center of European fashion. Dress codes are relaxed, but Italian women do not normally wear shorts in the cities. In churches, as we have seen, you may be forbidden to enter if you are wearing shorts or a sleeveless top.

One of the great delights of Italy is how much of life is lived outdoors, at least in the warmer months of the year. All large towns have more or less permanent outdoor markets and every village has a lively market day.

Sunday at the beach is a family ritual. After hours of preparation, the family emerges in public on the beach, the mother leading her flock to the chosen spot. As Tim Parks commented, in Italy, despite its individualism, people tend to do the same thing at the same time, whether it be tending a grave or going to the beach on June 18 after the end of the school year.

A characteristic of Southern life in particular is the passeggiata, a ritual more unmissable than Sunday mass. Young people gather in the hour or so before dinner and whole families put on their best clothes and walk arm-in-arm through the streets to see and be seen.

The Italians also enjoy camping, and Italy has over two thousand campsites, mostly open from April through September. They are graded according to facilities, from one to four stars; the best may have their own supermarkets, swimming pools, and cinemas. You may need an international camping ticket book: this can usually be bought at the campsite.

Tip for Campers

If you’re heading for a campsite, aim to arrive by 11:00 a.m. If you wait until after lunch, all the spaces may have gone.

Some observers have called football (soccer) Italy’s real religion. In Italy football is an art and is described as such by commentators and spectators alike. Watching the local team on a Sunday is an important event, and a national team’s success will be celebrated in banner headlines. The top teams such as Juventus (Turin), AC Milan, Inter Milan, and Lazio (Rome) are owned by leading business and political figures and are as much symbols of Italian pride as Benetton, Ferrari, Fiat, Armani, or Versace.

With the verbal felicity for which Italians are famed, footballers are given nicknames. Marco van Basten is called “the swan,” for example, and the Brazilian, Cafu, is “the little pendulum.”

In some ways, the rivalry between Italian clubs reflects the ancient rivalry between the medieval city-states; the drama is played out in stadiums across the country every week in season. Sit in any café (called bar in Italian) with its big screen and enjoy the exhilaration when the home team scores and share the misery when they lose a match. Strategy and tactics are discussed endlessly and with passion.

There is so much for the visitor to see in Italy, but where to start? A good idea is to visit the local office of the national tourist board, ENIT (Ente Nazionale Italiano di Turismo). They have offices in London and New York as well as at most of Italy’s border posts and airports. The state travel agency, CIT or CIT Italia (Sestante-Compagnia Italiana di Turismo), also provides information, and has a train-booking service. Each of Italy’s twenty provincial capitals has a local tourist office, called EPT (Ente Provinciale di Turismo) or APT (Azienda di Promozione Turistica). IAT (Ufficio Informazione e Accoglienza Turistica) and AAST (Azienda Autonoma di Soggiorno e Turismo) all provide maps, local information, public transport details, and opening times of the main sights in the area. Opening times are usually 8:30 a.m. to 7:00 p.m., Monday to Friday.

A National Call Center for English-speaking tourists is available on 800-117 700. It provides information in English on health care, safety, museums, accommodation, events, and shows.

As we have seen, the annual festa in an Italian town is an important event and can last several days. It may be a religious celebration, and it may also date back to Renaissance or medieval times: examples are the Palio horseback races in Siena (July 2 and August 16), the Regata in Venice (the first Sunday in September), and the Scoppio del Carro (“Firing of the Cart”) at Easter in Florence. On three days in June, one of which is always June 24, Florence is the venue for the sixteenth-century costume parade (Calcio Storico Fiorentino). There is also the lively sweet and toy fair from Christmas to January 5 in Rome’s Piazza Navona.

There are some seventy state-run museums in Italy, and one estimate says that the country is home to half the world’s great art treasures. Part of the reason is the extraordinary flowering of art and sculpture in Renaissance Italy, the legacy of which is visible in churches, palaces, and museums throughout the land. Almost every church seems to have its masterpiece—and almost every church wants to charge you 3 euros to enter and find it! Museums often close on Mondays, to compensate for being open on the weekend, and are usually open Tuesday through Saturday from 9:00 a.m. to 1:00 or 2:00 p.m. (later in big cities), and on Sundays from 9:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m.

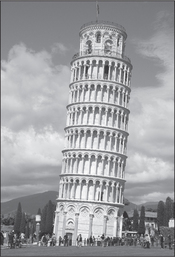

Some of the sites are so famous that you might think they are overrated: don’t be put off! The lines in the Vatican City may try your patience, but the soaring roof of the Sistine Chapel, once you squeeze through its narrow door, is breathtaking. The Villa Borghese in Rome is a gem, as are the Accademia and the Peggy Guggenheim Museum of Modern Art in Venice, and the Uffizi in Florence. Although Venice, Florence, and Rome draw the crowds, it is well worth visiting Naples, Palermo, and smaller towns such as Padua, Siena, and Pisa.

Some galleries such as the Villa Borghese require prior booking. Churches have a dress code. No bare shoulders or shorts, and visitors are asked not to wander around when a service is in progress.

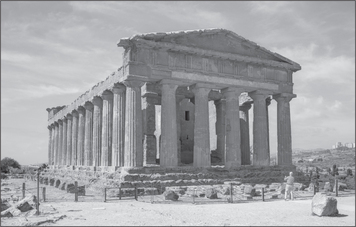

Some of the best-preserved monuments of ancient Greek civilization are found in southern Italy, known as Magna Graecia (Greater Greece) when it was a Greek colony. The most impressive temples are at Paestum (south of Naples), and at Selinunte, Agrigento, and Segesta in Sicily. The theater at Syracuse is the largest in the world.

One of the most memorable ways to gain a sense of Italy’s multilayered civilizations is to visit the church of San Clemente in Rome, overseen by Irish Dominicans. The eleventh-century upper church contains a magnificent Romanesque mosaic, but also Renaissance wall paintings and lavish Baroque decor. Under its floor you can visit a fourth-century church containing fragments of frescos, one of them with the oldest description in Italian. Descending even further, some 100 feet (30 meters) below street level, you find yourself in a narrow alley in ancient Rome leading to a first-century patrician house and a Mithraic temple.

For the glory that was Roman Italy, you must go to Pompeii and Herculaneum (Ercolano). Both were buried by the volcanic eruption of Mount Vesuvius, in 79 CE, and the site was not excavated until 1750. And, yes, if you’re in Naples, it’s worth the trip. Pompeii is open from 8:00 a.m. to 7:30 p.m., Monday through Saturdays, and you need three or four hours to take it all in.

The country of Verdi and Puccini is not short of opera houses and theaters. Italy hosts many world-renowned opera performances, and, if you speak Italian, you can see plays by names such as Pirandello and Dario Fo. The opera season runs from December to June, but there are summer festivals in open-air theaters.

One of the greatest outdoor concert venues is Verona’s huge first-century amphitheater, known as the “Arena,” which can seat an audience of up to 25,000. Large as it is, the Arena is dwarfed by Rome’s Colosseum, which, in its day, could hold 50,000 spectators. The most famous opera house is La Scala in Milan; you can book ahead on www.musica.it.

If you stroll around the piazza in front of the Doge’s Palace in Venice, sellers in eighteenth-century costume will give you fliers for baroque music in the Venetian style, performed in concert halls in the center of the city. Tourist trap though it may be, the music is usually enjoyable and respectably played. You’ll enjoy your late evening grappa in the famous Caffè Florian even more.

Music festivals are also popular in Italy. One of the most famous is the Festival of Two Worlds in Spoleto in June and July. The Sanremo Italian popular song festival (Festival della Canzone Italiana) in February is the equivalent of the Grammy or the Brit awards.

Apart from open-air festivals, all the opera houses and theaters, as well as the majority of cinemas, shut their doors in the summer. Entertainment moves outside with feasting, dancing, and music in the courtyards of old palazzos, and opera in city parks and amphitheaters. This is also the season for a thousand local festas, or festivals.

In Italy, almost all foreign films are dubbed. Italian cinema has a great tradition, however. Fellini’s old home in Via Marghera in Rome has a commemorative plaque outside, and Rome’s Cinecittà film studios were home to Sergio Leone’s “spaghetti westerns,” which made Clint Eastwood famous. In the major cities you will find at least one cinema showing English-language films in the original. The Venice Film Festival in August and September is the world’s oldest film festival (founded in 1932) and a major event in the international calendar. Venice’s Golden Lion is one of international cinema’s most prestigious awards.