Canning is one of the most popular preservation methods for food. However, it can be much more labor-intensive than freezing or drying foods, and you will need special equipment to process the food correctly. The benefits to canning, in spite of the extra trouble, are that many foods taste better when they are canned rather than frozen. Some produce, such as plums, apples, and carrots, develop a richer, complex taste in the canning process. In addition, your freezer usually has a small amount of room for storage, whereas canned foods can be piled up in a pantry, basement, or closet for years. Finally, there are some foods, such as pickles, that cannot complete the fermenting process in a freezer.

A Glossary of Canning Terms

Acid foods Foods that contain enough acid to result in a pH of 4.6 or lower. This includes all fruits except figs; most tomatoes; fermented and pickled vegetables; relishes; and jams, jellies, and marmalades. Acid foods may be processed in boiling water.

Altitude The vertical elevation of a location above sea level.

Ascorbic acid The chemical name for vitamin C. Lemon juice contains large quantities of ascorbic acid and is commonly used to prevent browning of peeled, light-colored fruits and vegetables.

Bacteria A large group of one-celled microorganisms widely distributed in nature. See microorganism.

Blancher A 6- to 8-quart lidded pot designed with a fitted perforated basket to hold food in boiling water, or with a fitted rack to steam foods. Useful for loosening skins on fruits to be peeled, or for heating foods to be hot packed.

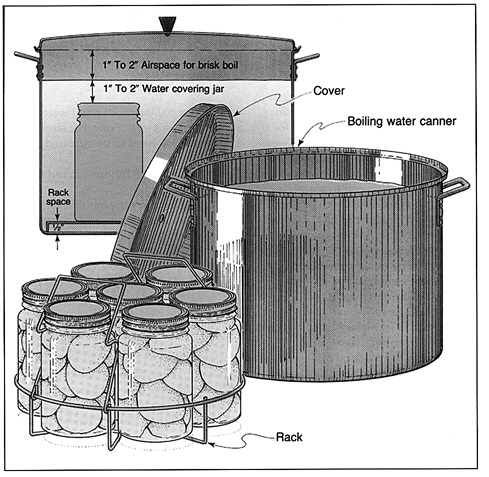

Boiling-water canner A large standard-sized lidded kettle with jar rack, designed for heat-processing 7 quarts or 8 to 9 pints in boiling water.

Botulism An illness caused by eating toxin produced by growth of Clostridium botulinum bacteria in moist, low-acid food, containing less than 2 percent oxygen, and stored between 40 degrees and 120 degrees F. Proper heat processing destroys this bacterium in canned food. Freezer temperatures inhibit its growth in frozen food. Low moisture controls its growth in dried food. High oxygen controls its growth in fresh foods.

Canning A method of preserving food in air-tight vacuum-sealed containers and heat processing sufficiently to enable storing the food at normal home temperatures.

Canning salt Also called pickling salt. It is regular table salt without the anticaking or iodine additives.

Citric acid A form of acid that can be added to canned foods. It increases the acidity of low-acid foods and may improve the flavor and color.

Cold pack Canning procedure in which jars are filled with raw food. “Raw pack” is the preferred term for describing this practice. “Cold pack” is often used incorrectly to refer to foods that are open-kettle canned or jars that are heat-processed in boiling water.

Enzymes Proteins in food which accelerate many flavor, color, texture, and nutritional changes, especially when food is cut, sliced, crushed, bruised, and exposed to air. Proper blanching or hot-packing practices destroy enzymes and improve food quality.

Exhausting Removal of air from within and around food and from jars and canners. Blanching exhausts air from live food tissues. Exhausting or venting of pressure canners is necessary to prevent a risk of botulism in low-acid canned foods.

Fermentation Changes in food caused by intentional growth of bacteria, yeast, or mold. Native bacteria ferment natural sugars to lactic acid, a major flavoring and preservative in sauerkraut and in naturally fermented dills. Alcohol, vinegar, and some dairy products are also fermented foods.

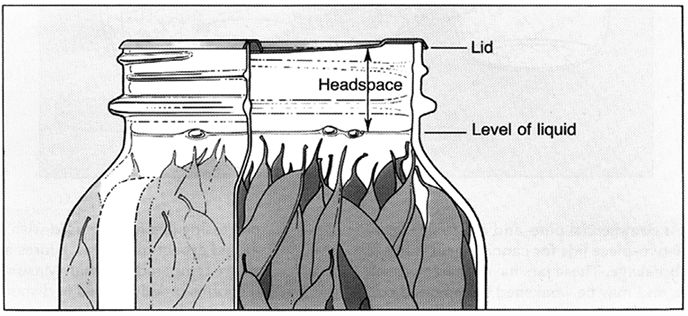

Headspace The unfilled space above food or liquid in jars. Allows for food expansion as jars are heated, and for forming vacuums as jars cool.

Heat processing Treatment of jars with sufficient heat to enable storing food at normal home temperatures.

Hermetic seal An absolutely airtight container seal that prevents reentry of air or microorganisms into packaged foods.

Hot pack Heating of raw food in boiling water or steam and filling it hot into jars.

Low-acid foods Foods that contain very little acid and have a pH above 4.6. The acidity in these foods is insufficient to prevent the growth of the bacterium Clostridium botulinum. Vegetables, some tomatoes, figs, all meats, fish, seafoods, and some dairy foods are low acid. To control all risks of botulism, jars of these foods must be (1) heat processed in a pressure canner, or (2) acidified to a pH of 4.6 or lower before processing in boiling water.

Micro-organisms Independent organisms of microscopic size, including bacteria, yeast, and mold. When alive in a suitable environment, they grow rapidly and may divide or reproduce every 10 to 30 minutes. Therefore, they reach high populations very quickly. Undesirable microorganisms cause disease and food spoilage. Microorganisms are sometimes intentionally added to ferment foods, make antibiotics, and for other reasons.

Mold A fungus-type microorganism whose growth on food is usually visible and colorful. Molds may grow on many foods, including acid foods like jams and jellies and canned fruits. Recommended heat processing and sealing practices prevent their growth on these foods.

Mycotoxins Toxins produced by the growth of some molds on foods.

Open-kettle canning A non-recommended canning method. Food is supposedly adequately heat processed in a covered kettle, and then filled hot and sealed in sterile jars. Foods canned this way have low vacuums or too much air, which permits rapid loss of quality in foods. Moreover, these foods often spoil because they become recontaminated while the jars are being filled.

Pasteurization Heating of a specific food enough to destroy the most heat-resistant pathogenic or disease-causing microorganism known to be associated with that food.

pH A measure of acidity or alkalinity. Values range from 0 to 14. A food is neutral when its pH is 7.0, lower values are increasingly more acidic, and higher values are increasingly more alkaline.

Pickling The practice of adding enough vinegar or lemon juice to a low-acid food to lower its pH to 4.6 or lower. Properly pickled foods may be safely heat processed in boiling water.

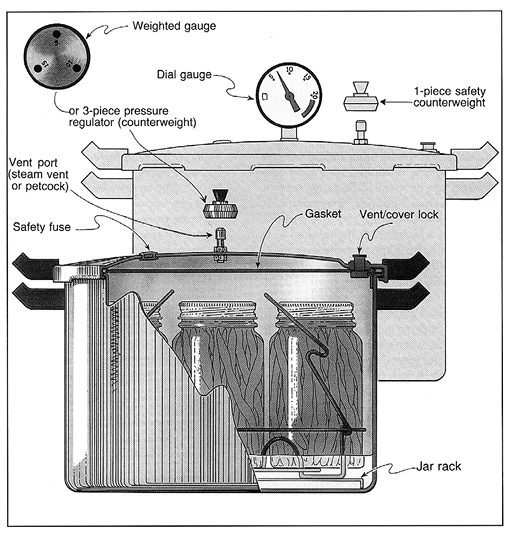

Pressure Canner A specifically designed metal kettle with a lockable lid used for heat processing low-acid food. These canners have jar racks, one or more safety devices, systems for exhausting air, and a way to measure or control pressure. Canners with 16- to 23- quart capacity are common. The minimum volume of canner that can be used is one that will contain 4 quart jars. Use of pressure saucepans with smaller capacities is not recommended.

Raw pack The practice of filling jars with raw, unheated food. Acceptable for canning low-acid foods, but it allows more rapid quality losses in acid foods heat processed in boiling water.

Spice bag A closeable fabric bag used to extract spice flavors in pickling solution.

Style of pack Form of canned food, such as whole, sliced, piece, juice, or sauce. The term may also be used to reveal whether food is filled raw or hot into jars.

Vacuum The state of negative pressure. Reflects how thoroughly air is removed from within a jar of processed food — the higher the vacuum, the less air left in the jar.

Yeasts A group of microorganisms which reproduce by budding. They are used in fermenting some foods and in leavening breads.

The goal of proper canning is to remove oxygen, destroy enzymes, and kill harmful microorganisms like mold, bacteria, and yeast. Proper canning will also produce jars with a strong vacuum seal that will prevent liquid from leaking out or microorganisms from getting into the food. Properly canned foods can last for several years. Proper canning practices include:

• Selecting fresh, undamaged foods

• Carefully inspecting and washing fruits and vegetables

• Peeling fresh foods, if necessary

• Using the hot packing method where appropriate

• Adding acids (lemon juice or vinegar) to foods that need

acid-packing

• Following recipes and directions precisely

• Using clean jars and lids that seal properly

• Using the right processing time when canning jars in a

boiling-water or pressure canner

Collectively, these practices remove oxygen; destroy enzymes; prevent the growth of undesirable bacteria, yeasts, and molds; and help form a high vacuum in jars. Good vacuums form tight seals, which keep liquid in and air and microorganisms out. Most health-related problems arise when people do not follow the canning directions properly. Today, canning experts agree that old methods of canning and outdated cookbooks give unhealthy or inaccurate directions for food safety. However, the Center for Home Food Preservation, working with the University of Georgia, interviewed home canners and found that they often used unsafe directions or instructions from friends or relatives.

Different methods are now considered best for different types of foods. The USDA recommends water bath or pressure-canning methods when preserving high-acid products such as pickles, fruits, and tomatoes. In the past, people canned these products with open-kettle canning, but experts no longer considered this a safe canning method. Oven and microwave procedures are also considered unsafe.

Equipment and methods not recommended

Courtesy of the USDA

Open-kettle canning and the processing of freshly filled jars in conventional ovens, microwave ovens, and dishwashers are not recommended, because these practices do not prevent all risks of spoilage. Steam canners are not recommended because processing times for use with current models have not been adequately researched. Because steam canners do not heat foods in the same manner as boiling-water canners, their use with boiling-water process times may result in spoilage. It is not recommended that pressure processes in excess of 15 PSI be applied when using new pressure canning equipment. So-called canning powders are useless as preservatives and do not replace the need for proper heat processing. Jars with wire bails and glass caps make attractive antiques or storage containers for dry food ingredients, but they are not recommended for use in canning. One-piece zinc porcelain-lined caps are also no longer recommended. Both glass and zinc caps use flat rubber rings for sealing jars, but they too often fail to seal properly.

The canning process works to sterilize food and then seal the foods so that no contamination can enter the jar. Sterilization happens during the hot water processing, which also creates a vacuum seal in the jar. In the past, many homemakers poured a layer of wax over foods such as jams and preserves before processing the seal. Most experts now consider this unsafe and unnecessary. In fact, modern lids produce a good vacuum seal without this additional step.

The vacuum seal is crucial, and is affected by the quality of the lids as well as the proper level of food and liquid in the jar — known as “headspace.” Each type of food has a different headspace depending on the food’s shrinkage or swelling during the boiling process. Be sure to follow the directions closely and use a ruler if you have any doubts. More information on headspace can be found later in this chapter.

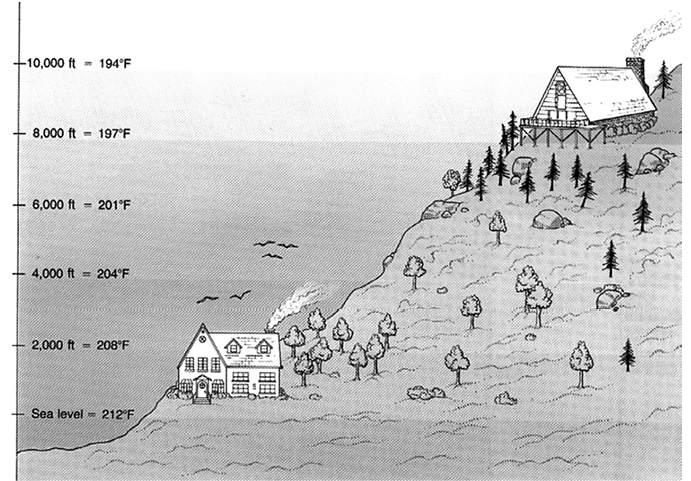

Each food has a different processing time to allow enough heat to kill microorganisms. In addition, these times increase with your altitude above sea level, because water boils at lower temperatures at higher altitudes. Foods with more acid, such as citrus fruits, tomatoes, and recipes with added vinegar or lemon juice have an additional antiseptic agent. The acid itself helps to sterilize the foods. Low-acid foods like meat and beans will need a much longer sterilization period.

Canning tools

Canning supplies that are part of a kit

You will need a few items to can your foods properly. The good news is that most of these items are probably already in your kitchen. Before you get started on a canning recipe, make sure you have the following accessories handy:

1. A jar lifter, which is a set of tongs specially made for canning jars with rubber-coated handles to lift hot jars out of the boiling water in the canner.

2. A small-bladed spatula — either plastic or rubber — to push out bubbles from jars before processing. Some instructions say to use a metal knife, but this may cause some fruits to change color.

3. An accurate kitchen timer, measuring cups, and spoons. Canning recipes are very exact, and proper timing and measuring are crucial to your success.

4. Saucepans to cook sauces and warm lids.

5. Colanders to drain.

6. Knives and cutting boards to cut and process fruits and vegetables.

7. Pot holders or mitts to protect hands from hot surfaces.

8. A large spoon to use for stirring.

9. Towels to use in the process of cooling your canning jars.

Canning jars

First, you will need to purchase or borrow canning jars. There are still many old-fashioned jars in circulation — perhaps you inherited some from a relative. These could be old, cracked jars or ones with a rubber gasket and clasp; these are likely to break during processing, and the clasp-type lids are not as safe for canning as modern jars and lids. Some recycled food containers are safe for use in a water-bath process, but cannot stand a pressure canner. Commercial mayonnaise jars are a particular concern due to their lack of heat-tempering and thin walls. They also have narrow rims that prevent a proper seal. Of course, many types of recycled food jars can be used for foods that you will refrigerate and use within a week or two. If you borrow or re-use canning jars, be sure to inspect them for nicks, cracks, or lid wear that could cause breakage — or even explosion in a pressure canner. Jars are safe to reuse if they can accommodate modern, flat canning lids and screw-on rings.

Your best choice is to purchase new jars made especially for canning from grocery stores, hardware stores, and the like. Quart jars are best for larger produce or meat pieces; pint and half-pint sizes are ideal for sauces, condiments, chutneys, jams, and jellies. Jars come in standard and wide-mouth varieties. Many prefer wide-mouth jars that are easier to fill and wash. Regular and wide-mouth Mason-type, threaded, home-canning jars with self-sealing lids are the best choice. They are available in ½ pint, 1 pint, 1 ½ pint, quart, and ½ gallon sizes. The standard jar mouth opening is about 2 3/8 inches. Wide-mouth jars have openings of about 3 inches, making them more easily filled and emptied. Half-gallon jars may be used for canning very acidic juices. Regular-mouth decorator jelly jars are available in 8 and 12 ounce sizes. With careful use and handling, Mason jars may be reused many times, requiring only new lids each time. When jars and lids are used properly, jar seals and vacuums are excellent and jar breakage is rare.

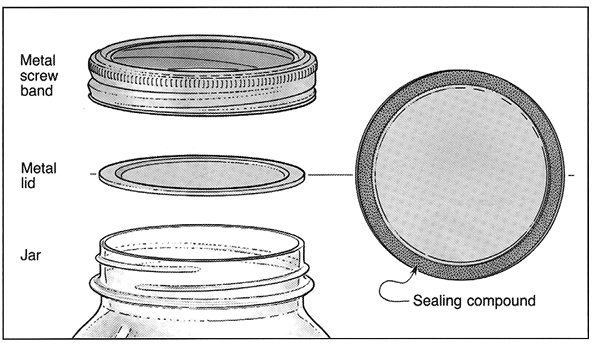

Today, safe canning requires the self-sealing, two-piece vacuum lid that can be found anywhere canning jars are purchased. These flat metal lids have a rubber gasket strip molded to a crimped underside. A metal band screws onto the jar to hold the lid in place. When you process the jars in a hot water bath, the compound softens and begins to seal while still allowing air to escape from the jar. When you allow the jars to cool after processing, the lid seals itself and creates a vacuum within the jar. For this reason, lids should never be re-used, but the metal bands can be removed after canning and used repeatedly. Be sure to check the metal bands for any signs of rust before using, because the rust can prevent a proper seal. Buy only the quantity of lids you will use in a year. To ensure a good seal, carefully follow the manufacturer’s directions in preparing lids for use. Examine all metal lids carefully. Do not use old, dented, or deformed lids, or lids with gaps or other defects in the sealing gasket.

Courtesy of the USDA

Jar cleaning and preparation

Before every use, wash empty jars in hot water with detergent and rinse well by hand, or wash in a dishwasher. Unrinsed detergent residues may cause unnatural flavors and colors. Jars should be kept hot until ready to fill with food. Submerge the clean empty jars in enough water to cover them in a large stockpot or boiling water canner. Bring the water to a simmer (180 degrees F) and keep the jars in the simmering water until it is time to fill them with food. A dishwasher may be used for preheating jars if they are washed and dried on a complete, regular cycle. Keep the jars in the closed dishwasher until needed for filling.

These washing and preheating methods do not sterilize jars. Some used jars may have a white film on the exterior surface caused by mineral deposits. This scale or hard-water film on jars is easily removed by soaking jars several hours in a solution containing 1 cup of vinegar (5 percent acidity) per gallon of water prior to washing and preheating the jars.

Another method is to put all of the jars, lids, bands, tongs, and any other items that will contact the food into a large pot and boil the items for ten minutes. Keep the sterile items in the pot until you are ready to use them. Do not touch sterilized supplies with your hands or any unsterilized tools — this will contaminate your sterile supplies. If you boil the equipment at the time you are preparing your foods for packing, the hot-pack foods will go straight into hot jars and minimize stress on the glass.

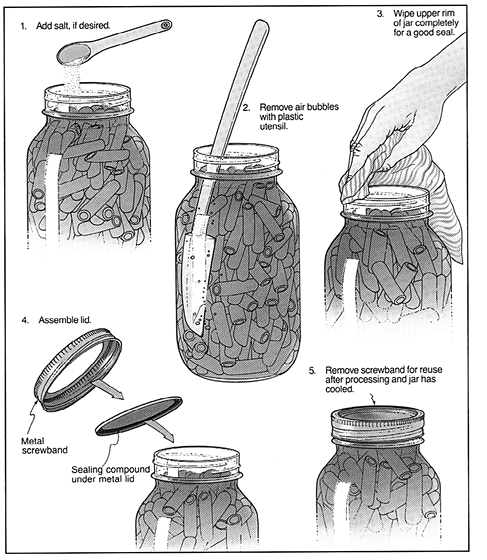

Illustration courtesy of the USDA

Canning Guidelines

Hot pack vs. raw pack

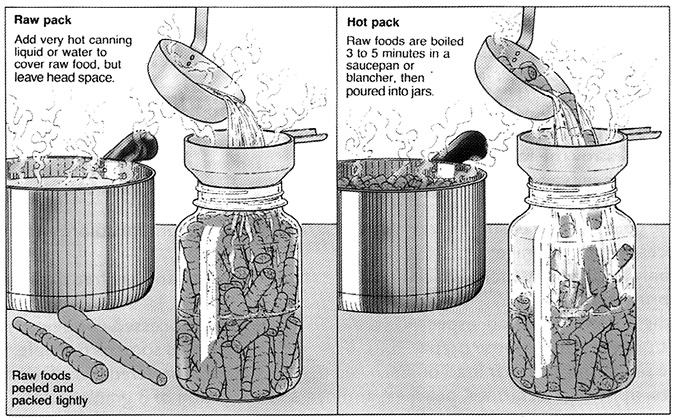

When packing food (and any juices or spices) into canning jars, there are two ways you can do it: hot pack or raw pack. To hot pack food, you will boil some kind of liquid, juice, or broth, and cook the food slightly before putting it into hot jars. The raw pack method requires you to tightly pack raw food into jars, and then cover with boiling water, syrup, juice, or broth to the proper headspace. Each canning recipe will indicate which method is best, though some items can be packed either raw or hot.

The hot pack method works best for firm produce or meats that either need a cooked sauce or will taste best with a processed syrup or broth. In addition, hot-packed foods will contain less air, will inactivate enzymes, and preserve the bright color of the produce. To hot pack foods, fold them into a boiling syrup, juice, or water. Then pack the produce into hot, sterile jars to prevent the glass from cracking, and to eliminate food-borne illnesses. Ladle the juice or broth into the jars until it reaches the required headspace. You may need to tap the jar on a counter or slide a spatula down between the jar and produce to remove any bubbles. Seal the jars, and then process them in a water-bath canner. Because these foods are partially cooked, hot packed produce requires less processing time. Recipes should indicate the proper processing time and the hot pack process.

Raw pack (or cold pack) works best for delicate foods like berries or some types of pickles. Cold packing is quicker and easier, but the processing time is longer. Make sure to pack the produce as tightly as possible into hot, sterile jars. Then pour in the hot syrup, juice, or water to fill spaces and submerge the contents. Again, you may need to tap the jar on a counter or slide a spatula down the insides of the jars to remove any bubbles. Seal the jars, and then follow the recipe’s directions to process them in a hot water canner.

Illustration courtesy of the USDA

Headspace

The space between the food and liquid and the top rim of the jar is called the headspace. Proper headspace is crucial to a good seal. This space will allow the food and air to expand and move while it is heated. The air will expand much more than the food does, and the higher the temperature, the more the air will expand. If you fill the jar too full, the food will swell and spurt out of the jar, ruining the seal. This causes a mess in your canner, too. Even if you wipe off the jar, food may be trapped under the seal and will cause the food to rot. The best remedy is to sterilize the jar and lid, and re-process that jar with the correct headspace.

Illustration courtesy of the USDA

As the jars cool, the food, liquid, and air begins to contract; this pulls down the lid to create a vacuum seal that protects your food. You have probably noticed the characteristic hiss as you open a jar of food and the vacuum releases. However, if there is too much headspace for the specific food, the product has too much room to set a strong vacuum as the jars cool. Always make sure the lid is concave when fully cooled, as this indicates a good seal.

Canning recipes should always indicate the right amount of headspace. Make sure you follow the instructions carefully. As a general guideline, vegetables and fruits usually need ½ inch of headspace if processed in a boiling water canner. Produce, meat, and other recipes processed in a pressure canner should generally have 1 inch of headspace. Jams and jellies need ¼ inch of headspace.

Altitude adjustments

The canning recipes in this book call for a specific processing time and, with pressure canners, a specific amount of pressure. These instructions are intended for people who are processing food at altitudes ranging from sea level to 1,000 feet above sea level. However, those same processing times used at higher altitudes may not be sufficient and can cause the food to spoil. The reason for this is that water boils at a lower temperature at higher altitudes; the lower temperature may not be sufficient to destroy all the bacteria and mold.

Illustration courtesy of the USDA

If you live at a high altitude, you are probably familiar with adjusting many types of recipes to work with your area. When using a pressure canner at altitudes above 1,000 feet, add ½ pound more pressure for each 1,000 in altitude. If your pressure canner does not have a dial gauge that allows you to make small adjustments, increase the weighted gauge to the next mark. For example, if your recipe calls for 10 pounds of pressure at 1,000 feet, process it at 15 pounds of pressure at high altitudes. When processing high-acid foods in a water-bath canner at altitudes above 1,000 feet, add 5 minutes of processing time. For low-acid foods, add 10 minutes for each 1,000 in altitude. These are only general guidelines; your particular area may vary. If you have questions about your altitude, proper pressures, or canning times, check with your county extension office.

Determining Your Altitude Above Sea Level

Courtesy of the USDA

It is important to know your approximate elevation or altitude above sea level in order to determine a safe processing time for canned foods. Because the boiling temperature of liquid is lower at higher elevations, it is critical that additional time be given for the safe processing of foods at altitudes above sea level.

It is not practical to include a list of altitudes in this guide, because there is wide variation within a state and even a county. For example, the state of Kansas has areas with altitudes varying between 75 ft to 4,039 ft above sea level. Kansas is not generally thought to have high altitudes, but there are many areas of the state where adjustments for altitude must be considered. Colorado, on the other hand, has people living in areas between 3,000 and 10,000 ft above sea level. They tend to be more conscious of the need to make altitude adjustments in the various processing schedules. To list altitudes for specific counties may actually be misleading, due to the differences in geographic terrain within a county.

If you are unsure about the altitude where you will be canning foods, consult your county extension agent. An alternative source of information would be your local district conservationist with the Soil Conservation Service.

Boiling water bath canners

These types of canners are large metal or porcelain-lined pots that have a removable canning rack and a lid. These are inexpensive and easily found in department or hardware stores. Buy a size that will be no more than 4 inches wider than your stove burners, so that the water will process food evenly.

During water-bath processing, jars are placed on top of the canning rack, and then the pot is filled with water. Make sure you fill the canner so at least an inch of water covers the tops of the jars. The water is heated to boiling, and once a full rolling boil is attained, you begin timing the processing according to the recipe’s directions. Some boiling-water canners do not have flat bottoms. A flat bottom must be used on an electric range. Either a flat or ridged bottom can be used on a gas burner. To ensure uniform processing of all jars with an electric range, the canner should be no more than 4 inches wider in diameter than the element on which it is heated.

Boiling water bath canning is suitable only for foods containing high acid, like many fruits and pickles; the acid content helps to destroy toxins and harmful microorganisms. Lower-acid foods need a longer processing time and the heat concentration of a pressure canner to raise the temperature high enough to kill the same microorganisms.

Illustration courtesy of the USDA

How to use a water bath canner

Instructions courtesy of the USDA

1. Before you start preparing your food, fill the canner halfway with clean water. This is approximately the level needed for a canner load of pint jars. For other sizes and numbers of jars, the amount of water in the canner will need to be adjusted so it will be 1 to 2 inches over the top of the filled jars.

2. Preheat water to 140 degrees F for raw-packed foods and to 180 degrees F for hot-packed foods. Food preparation can begin while this water is preheating.

3. Load filled jars, fitted with lids, into the canner rack and use the handles to lower the rack into the water; or fill the canner with the rack in the bottom, one jar at a time, using a jar lifter. When using a jar lifter, make sure it is securely positioned below the neck of the jar (below the screw band of the lid). Keep the jar upright at all times. Tilting the jar could cause food to spill into the sealing area of the lid.

4. Add more boiling water, if needed, so the water level is at least 1 inch above jar tops. For process times longer than 30 minutes, the water level should be at least 2 inches above the tops of the jars.

5. Turn heat to its highest position, cover the canner with its lid, and heat until the water in the canner boils vigorously.

6. Set a timer for the total minutes required for processing the food.

7. Keep the canner covered and maintain a boil throughout the process schedule. The heat setting may be lowered a little as long as a complete boil is maintained for the entire process time. If the water stops boiling at any time during the process, bring the water back to a vigorous boil and begin the timing of the process over, from the beginning.

8. Add more boiling water, if needed, to keep the water level above the jars.

9. When jars have been boiled for the recommended time, turn off the heat and remove the canner lid. Wait 5 minutes before removing jars.

10. Using a jar lifter, remove the jars and place them on a towel, leaving at least 1 inch spaces between the jars during cooling. Let jars sit undisturbed to cool at room temperature for 12 to 24 hours.

Pressure canners

Pressure canners for use in the home have been extensively redesigned in recent years. Models made before the 1970s were heavy-walled kettles with clamp-on or turn-on lids. They were fitted with a dial gauge, a vent port in the form of a petcock or counterweight, and a safety fuse. All low-acid foods must be processed in a pressure canner. This is a different kitchen appliance than a pressure cooker — it is designed to accommodate large canning jars and produces the proper temperature for canned food processing. An average canner can hold about seven quart jars or up to nine pint jars. Smaller canners can hold four quart jars.

A 16-quart pressure canner

Pressure does not destroy microorganisms, but high temperatures applied for an adequate period of time do kill microorganisms. The success of destroying all microorganisms capable of growing in canned food is based on the temperature obtained in pure steam, free of air, at sea level. At sea level, a canner operated at a gauge pressure of 10.5 lbs provides an internal temperature of 240 degrees F.

A pressure canner has a locking lid that holds in the steam and allows the pressure to build up, along with the heat. Either a pressure canner has a pressure gauge that shows the settings — 5,10, or 15 pounds — or a dial gauge that monitors rises in pressure from 5 to 15 pounds. If you live at a higher altitude, the dial gauge will be easier for you to use, because you must increase the pressure by a ½ pound for each 1,000 feet above sea level. If you use a dial gauge, be sure to have it checked every year at your county extension office.

Illustration courtesy of the USDA

Two serious errors in temperatures obtained in pressure canners occur because:

1. Internal canner temperatures are lower at higher altitudes. To correct this error, canners must be operated at the increased pressures.

2. Air trapped in a canner lowers the temperature obtained at 5, 10, or 15 pounds of pressure and results in under processing. The highest volume of air trapped in a canner occurs in processing raw-packed foods in dial-gauge canners. These canners do not vent air during processing. To be safe, all types of pressure canners must be vented 10 minutes before they are pressurized.

To vent a canner, leave the vent port uncovered on newer models or manually open petcocks on some older models. Heating the filled canner with its lid locked into place boils water and generates steam that escapes through the petcock or vent port. When steam first escapes, set a timer for 10 minutes. After venting 10 minutes, close the petcock or place the counterweight or weighted gauge over the vent port to pressurize the canner.

Weighted-gauge models exhaust tiny amounts of air and steam each time their gauge rocks or jiggles during processing. They control pressure precisely and need neither watching during processing nor checking for accuracy. The sound of the weight rocking or jiggling indicates that the canner is maintaining the recommended pressure. The single disadvantage of weighted-gauge canners is that they cannot correct precisely for higher altitudes. At altitudes above 1,000 feet, they must be operated at canner pressures of 10 instead of 5, or 15 instead of 10, PSI.

Check dial gauges for accuracy before use each year. Gauges that read high cause under-processing and may result in unsafe food. Low readings cause over-processing. Pressure adjustments can be made if the gauge reads up to 2 pounds high or low. Replace gauges that differ by more than 2 pounds. Every pound of pressure is very important to the temperature needed inside the canner for producing safe food, so accurate gauges and adjustments are essential when a gauge reads higher than it should. If a gauge is reading lower than it should, adjustments may be made to avoid over processing, but are not essential to safety. Gauges may be checked at many county cooperative extension offices, or consumers can contact the pressure canner manufacturer for other options.

Handle canner lid gaskets carefully and clean them according to the manufacturer’s directions. Nicked or dried gaskets will allow steam leaks during pressurization of canners. Keep gaskets clean between uses. Gaskets on older model canners may require a light coat of vegetable oil once per year. Gaskets on newer model canners are prelubricated and do not benefit from oiling. Check your canner’s instructions if there is doubt that the particular gasket you use has been prelubricated.

Lid safety fuses are thin metal inserts or rubber plugs designed to relieve excessive pressure from the canner. Do not pick at or scratch fuses while cleaning lids. Use only canners that have the Underwriters Laboratory (UL) approval to ensure their safety.

Replacement gauges and other parts for canners are often available at stores offering canning equipment or from canner manufacturers. When ordering parts, give your canner model number and describe the parts needed.

Using pressure canners

Instructions courtesy of the USDA

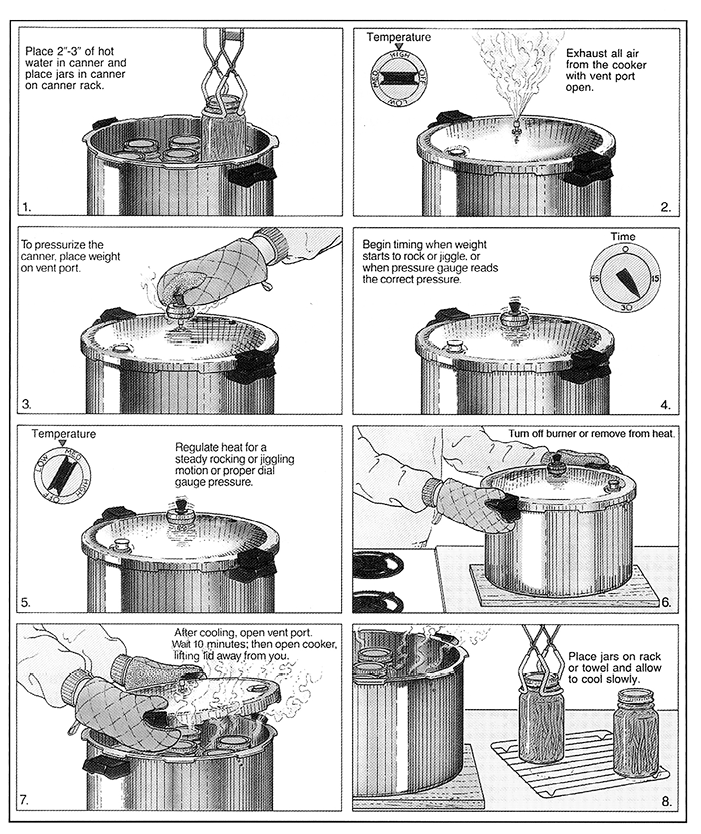

Follow these steps for successful pressure canning:

1. Put 2 to 3 inches of hot water in the canner. Some specific products in this guide require that you start with even more water in the canner. Always follow the directions for specific foods if they require more water added to the canner. Place filled jars on the rack, using a jar lifter. When using a jar lifter, make sure it is securely positioned below the neck of the jar (below the screw band of the lid). Keep the jar upright at all times. Tilting the jar could cause food to spill into the sealing area of the lid. Fasten canner lid securely.

2. Leave weight off vent port or open petcock. Heat at the highest setting until steam flows freely from the open petcock or vent port.

3. While maintaining the high heat setting, let the steam flow (exhaust) continuously for 10 minutes, and then place the weight on the vent port or close the petcock. The canner will pressurize during the next 3 to 5 minutes.

4. Start timing the process when the pressure reading on the dial gauge indicates that the recommended pressure has been reached, or when the weighted gauge begins to jiggle or rock as the canner manufacturer describes.

Illustration courtesy of the USDA

5. Regulate heat under the canner to maintain a steady pressure at, or slightly above, the correct gauge pressure. Quick and large pressure variations during processing may cause unnecessary liquid losses from jars. Follow the canner manufacturer’s directions for how a weighted gauge should indicate it is maintaining the desired pressure.

IMPORTANT: If at any time pressure goes below the recommended amount, bring the canner back to pressure and begin the timing of the process over, from the beginning (using the total original process time). This is important for the safety of the food.

6. When the timed process is completed, turn off the heat, remove the canner from heat if possible, and let the canner depressurize. Do not force-cool the canner. Forced cooling may result in unsafe food or food spoilage. Cooling the canner with cold running water or opening the vent port before the canner is fully depressurized will cause loss of liquid from jars and seal failures. Force-cooling may also warp the canner lid of older model canners, causing steam leaks. Depressurization of older models without dial gauges should be timed. Standard-size heavy-walled canners require about 30 minutes when loaded with pints and 45 minutes with quarts. Newer thin-walled canners cool more rapidly and are equipped with vent locks. These canners are depressurized when their vent lock piston drops to a normal position.

7. After the canner is depressurized, remove the weight from the vent port or open the petcock. Wait 10 minutes, unfasten the lid, and remove it carefully. Lift the lid away from you so that the steam does not burn your face.

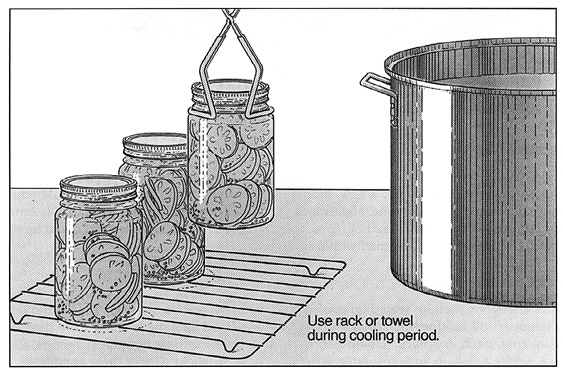

8. Remove jars with a jar lifter, and place them on a towel, leaving at least 1-inch spaces between the jars during cooling. Let jars sit undisturbed to cool at room temperature for 12 to 24 hours.

Cooling jars

When you remove hot jars from a canner, do not retighten their jar lids. Retightening of hot lids may cut through the gasket and cause seal failures. Cool the jars at room temperature for 12 to 24 hours. Jars can be cooled on racks or towels to minimize heat damage to counters. The food level and liquid volume of raw-packed jars will be noticeably lower after cooling. Air is exhausted during processing and food shrinks. If a jar loses excessive liquid during processing, do not open it to add more liquid.

Illustration courtesy of the USDA

Testing jar seals

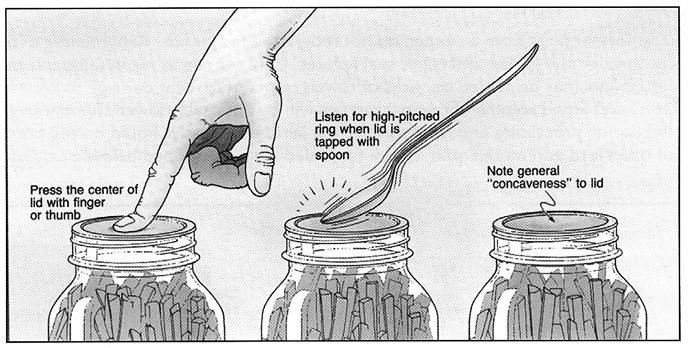

After cooling jars for 12 to 24 hours, remove the screw bands and test seals with one of the following options:

• Press the middle of the lid with a finger or thumb. If the lid springs up when you release your finger, the lid is unsealed.

• Tap the lid with the bottom of a teaspoon. If it makes a dull sound, the lid is not sealed. If food is in contact with the underside of the lid, it will also cause a dull sound. If the jar is sealed correctly, it will make a ringing, high-pitched sound.

• Hold the jar at eye level and look across the lid. The lid should be concave (curved down slightly in the center). If center of the lid is either flat or bulging, it might not be sealed.

Illustration courtesy of the USDA

Reprocessing unsealed jars

If a lid fails to seal on a jar, remove the lid and check the jar-sealing surface for tiny nicks. If necessary, change the jar, add a new, properly prepared lid, and reprocess within 24 hours using the same processing time. Headspace in unsealed jars may be adjusted to 1 ½ inches and jars could be frozen instead of reprocessed. Foods in single unsealed jars could be stored in the refrigerator and consumed within several days.

Storing jars

Store your jars in a dark, dry, cool place away from heat sources, and protect them from freezing. You can remove the screw bands from the lids if you wish, but some prefer to use those bands to secure the lids after the first time you open the jar. Label and date the jars and store them in a clean, cool, dark, dry place. Do not store jars above 95 degrees F or near hot pipes, a range, a furnace, under a sink, in a non-insulated attic, or in direct sunlight. Under these conditions, food will lose quality in a few weeks or months and may spoil. Dampness may corrode metal lids, break seals, and allow recontamination and spoilage.

What to Can?

There are many different foods you are able to can. The following section discusses popular foods to can and how these foods should be prepared. Also discussed are variations you can use in your canning for special diets.

Preparing pickled and fermented foods

The many varieties of pickled and fermented foods are classified by ingredients and method of preparation.

Regular dill pickles and sauerkraut are fermented and cured for about 3 weeks. Refrigerator dills are fermented for about 1 week. During curing, colors and flavors change and acidity increases. Fresh-pack or quick-process pickles are not fermented; some are brined several hours or overnight, then drained and covered with vinegar and seasonings. Fruit pickles usually are prepared by heating fruit in a seasoned syrup acidified with either lemon juice or vinegar. Relishes are made from chopped fruits and vegetables that are cooked with seasonings and vinegar.

Be sure to remove and discard a 1/16-inch slice from the blossom end of fresh cucumbers. Blossoms may contain an enzyme which causes excessive softening of pickles.

Caution: The level of acidity in a pickled product is as important to its safety as it is to taste and texture.

• Do not alter vinegar, food, or water proportions in a recipe or use a vinegar with unknown acidity.

• Use only recipes with tested proportions of ingredients.

• There must be a minimum, uniform level of acid throughout the mixed product to prevent the growth of botulinum bacteria.

Pickling ingredients

Select fresh, firm fruits or vegetables free of spoilage. Measure or weigh amounts carefully, because the proportion of fresh food to other ingredients will affect flavor and, in many instances, safety.

Use canning or pickling salt. Noncaking material added to other salts may make the brine cloudy. Because flake salt varies in density, it is not recommended for making pickled and fermented foods. White granulated and brown sugars are most often used. Corn syrup and honey, unless called for in reliable recipes, may produce undesirable flavors. White distilled and cider vinegars of 5 percent acidity (50 grain) are recommended. White vinegar is usually preferred when light color is desirable, as is the case with fruits and cauliflower.

Pickles with reduced salt content

In the making of fresh-pack pickles, cucumbers are acidified quickly with vinegar. Use only tested recipes formulated to produce the proper acidity. Although these pickles may be prepared safely with reduced or no salt, their quality may be noticeably lower. Both texture and flavor might be slightly, but noticeably, different than expected. You may wish to make small quantities first to determine if you like them.

However, the salt used in making fermented sauerkraut and brined pickles not only provides characteristic flavor but also is vital to safety and texture. In fermented foods, salt favors the growth of desirable bacteria while inhibiting the growth of others. Caution: Do not attempt to make sauerkraut or fermented pickles by cutting back on the salt required.

Firming agents

Alum may be safely used to firm fermented pickles. However, it is unnecessary and is not included in the recipes in this publication. Alum does not improve the firmness of quick-process pickles. The calcium in lime definitely improves pickle firmness. Food-grade lime may be used as a lime-water solution for soaking fresh cucumbers 12 to 24 hours before pickling them. Excess lime absorbed by the cucumbers must be removed to make safe pickles. To remove excess lime, drain the lime-water solution, rinse, and then resoak the cucumbers in fresh water for 1 hour. Repeat the rinsing and soaking steps two more times.

To further improve pickle firmness, you may process cucumber pickles for 30 minutes in water at 180 degrees Fahrenheit. This process also prevents spoilage, but the water temperature should not fall below 180 degrees F. Use a candy or jelly thermometer to check the water temperature.

Preventing spoilage

Pickle products are subject to spoilage from microorganisms, particularly yeasts and molds, as well as enzymes that may affect flavor, color, and texture. Processing the pickles in a boiling-water canner will prevent both of these problems. Standard canning jars and self-sealing lids are recommended. Processing times and procedures will vary according to food acidity and the size of food pieces.

Preparing butters, jams, jellies, and marmalades

Sweet spreads are a class of foods with many textures, flavors, and colors. They all consist of fruits preserved mostly by means of sugar and they are thickened or jellied to some extent. Fruit jelly is a semi-solid mixture of fruit juice and sugar that is clear and firm enough to hold its shape. Other spreads are made from crushed or ground fruit.

Jam also will hold its shape, but it is less firm than jelly. Jam is made from crushed or chopped fruits and sugar. Jams made from a mixture of fruits are usually called conserves, especially when they include citrus fruits, nuts, raisins, or coconut. Preserves are made of small, whole fruits or uniform-size pieces of fruits in a clear, thick, slightly jellied syrup. Marmalades are soft fruit jellies with small pieces of fruit or citrus peel evenly suspended in a transparent jelly. Fruit butters are made from fruit pulp cooked with sugar until thickened to a spreadable consistency.

Ingredients

For proper texture, jellied fruit products require the correct combination of fruit, pectin, acid, and sugar. The fruit gives each spread its unique flavor and color. It also supplies the water to dissolve the rest of the necessary ingredients and furnishes some or all of the pectin and acid. Good-quality, flavorful fruits make the best jellied products.

Pectins are substances in fruits that form a gel if they are in the right combination with acid and sugar. All fruits contain some pectin. Apples, crab apples, gooseberries, and some plums and grapes usually contain enough natural pectin to form a gel. Other fruits, such as strawberries, cherries, and blueberries, contain little pectin and must be combined with other fruits high in pectin or with commercial pectin products to obtain gels. Because fully ripened fruit has less pectin, one-fourth of the fruit used in making jellies without added pectin should be under-ripe.

Caution: Commercially frozen and canned juices may be low in natural pectins and make soft-textured spreads.

The proper level of acidity is critical to gel formation. If there is too little acid, the gel will never set; if there is too much acid, the gel will lose liquid (weep). For fruits low in acid, add lemon juice or other acid ingredients as directed. Commercial pectin products contain acids, which help to ensure gelling.

Sugar serves as a preserving agent, contributes flavor, and aids in gelling. Cane and beet sugar are the usual sources of sugar for jelly or jam. Corn syrup and honey may be used to replace part of the sugar in recipes, but too much will mask the fruit flavor and alter the gel structure. Use tested recipes for replacing sugar with honey and corn syrup. Do not try to reduce the amount of sugar in traditional recipes. Too little sugar prevents gelling and may allow yeasts and molds to grow.

Jams and jellies with reduced sugar

Jellies and jams that contain modified pectin, gelatin, or gums may be made with noncaloric sweeteners. Jams with less sugar than usual also can be made with concentrated fruit pulp, which contains less liquid and less sugar.

Two types of modified pectin are available for home use. One gels with one-third less sugar. The other is a low-methoxyl pectin, which requires a source of calcium for gelling. To prevent spoilage, jars of these products might need to be processed longer in a boiling-water canner. Recipes and processing times provided with each modified pectin product must be followed carefully. The proportions of acids and fruits should not be altered, because spoilage may result. Acceptably gelled refrigerator fruit spreads also may be made with gelatin and sugar substitutes. Such products spoil at room temperature, must be refrigerated, and should be eaten within 1 month.

Preventing spoilage

Even though sugar helps preserve jellies and jams, molds can grow on the surface of these products. Research now indicates that the mold, which people usually scrape off the surface of jellies, may not be as harmless as it seems. Mycotoxins have been found in some jars of jelly having surface mold growth. Mycotoxins are known to cause cancer in animals; their effects on humans are still being researched. Because of possible mold contamination, paraffin or wax seals are no longer recommended for any sweet spread, including jellies. To prevent growth of molds and loss of good flavor or color, fill products hot into sterile Mason jars, leaving ¼-inch headspace, seal with self-sealing lids, and process 5 minutes in a boiling-water canner. Correct process time at higher elevations by adding 1 additional minute per 1,000 ft above sea level. If unsterile jars are used, the filled jars should be processed for 10 minutes. Use of sterile jars is preferred, especially when fruits are low in pectin, because the added 5-minute process time may cause weak gels.

Methods of making jams and jellies

There are two methods to make jams and jellies. The standard method, which does not require added pectin, works best with fruits naturally high in pectin. The other method, which requires the use of commercial liquid or powdered pectin, is much quicker. The gelling ability of various pectins differs. To make uniformly gelled products, be sure to add the quantities of commercial pectins to specific fruits as instructed on each package. Overcooking can break down pectin and prevent proper gelling. When using either method, make one batch at a time, according to the recipe. Increasing the quantities often results in soft gels. Stir constantly while cooking to prevent burning. Recipes are developed for specific jar sizes. If jellies are filled into larger jars, excessively soft products may result.

Canned foods for special diets

The cost of commercially canned special-diet food often prompts interest in preparing these products at home. Some low-sugar and low-salt foods may be easily and safely canned at home. However, the color, flavor, and texture of these foods may be different than expected and be less acceptable.

Canning without sugar

In canning regular fruits without sugar, it is very important to select fully ripe but firm fruits of the best quality. Prepare these as described for hot-packs, but use water or regular unsweetened fruit juices instead of sugar syrup. Juice made from the fruit being canned is best. Blends of unsweetened apple, pineapple, and white grape juice are also good for filling over solid fruit pieces. Adjust headspaces and lids and use the processing recommendations given for regular fruits. Splenda® is the only sugar substitute currently in the marketplace that can be added to covering liquids before canning fruits. Other sugar substitutes, if desired, should be added when serving.

Canning without salt (reduced sodium)

To can tomatoes, vegetables, meats, poultry, and seafood with reduced sodium, simply omit the salt. In these products, salt seasons the food but is not necessary to ensure its safety. Add salt substitutes, if desired, when serving.

Canning fruit-based baby foods

You may prepare any chunk-style or pureed fruit with or without sugar. Pack in half-pint, preferably, or pint jars and use the following processing times.

Recommended process time for fruit-based baby foods in a boiling-water canner

|

Process Time at Altitudes of |

||||

|

Style of Pack |

Jar |

0- |

1,001- |

Above |

|

Hot |

Pints |

20 min |

25 min |

30 min |

Caution: Do not attempt to can pureed vegetables, red meats, or poultry meats, because proper processing times for pureed foods have not been determined for home use. Instead, can and store these foods using the standard processing procedures; puree or blend them at serving time. Heat the blended foods to boiling, simmer for 10 minutes, cool, and serve. Store unused portions in the refrigerator and use within 2 days for best quality.

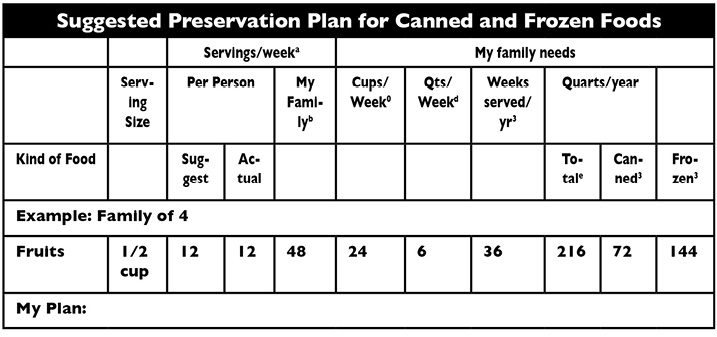

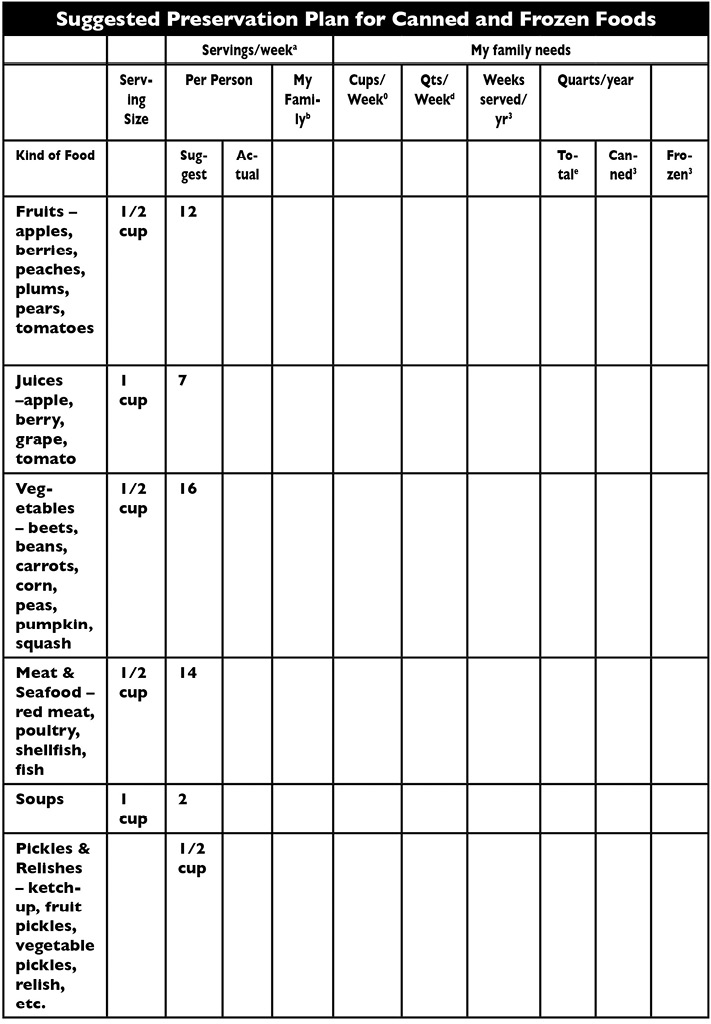

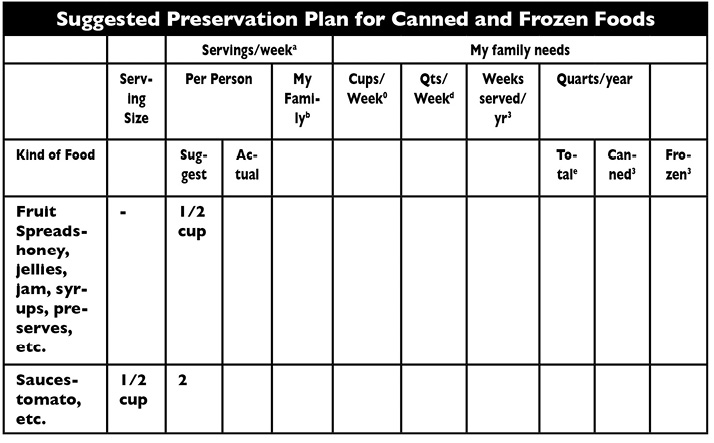

How much should you can?

The amount of food to preserve for your family, either by canning or freezing, should be based on individual choices. The following table can serve as a worksheet to plan how much food you should can for use within a year.

Total quarts/year = quarts/week multiplied by weeks served/year.