Let’s be reasonable: a single chapter won’t do the kitchen justice. However, a new attitude and a few baby steps in the direction of cooking and eating at home will set you on an exciting new track to not hating (or fearing) your kitchen.

First, I need to share a few things I’m probably not supposed to tell you: I don’t enjoy the everyday aspect of cooking, and you’ll never hear me say how therapeutic it is to put dinner together every night (though, pounding the hell out of a dough ball is cathartic—see the bread making section). I’m the special projects coordinator of our house, i.e., good at flashy, every few days kinds of things, not everyday things. I’m not great at following directions and I pride myself on imprecision (yes, gasp, even as our house’s baker and pastry maker).

I don’t read newspaper and magazine articles on gourmet food. I don’t like it when people use the word phenomenal in reference to food (or ever, really). I wouldn’t consider myself a foodie, and I’m still shocked when people refer to me as a food blogger/writer. If I can learn to love the kitchen under these circumstances, then certainly you can too.

In this chapter, we’ll start with the basics, like how to grocery-shop. We’ll move on to building your kitchen ecosystem, inserting homemade items gradually, then phase into a functioning, pride-inducing kitchen that’s ready for anything, like making dinner.

Open your fridge right now. Can you make a meal with anything in there at this very moment? Let’s change what you have on hand from sriracha sauce, a couple of containers of yogurt, and a rock-hard lemon into ready-to-use components of meals. In the next chapter we’ll cover how to stash meal components (in the freezer or in jars on the back shelf of your pantry) so they don’t go bad before you get to them.

Developing a relationship with your kitchen is less about touting easy and fast ways to be an at-home gourmet (which are handy tips to seek) and more about actually using your kitchen as a grown-up. This means taking charge of what goes into your body (something restaurant eating frequently prohibits) and how great it feels when the tide miraculously shifts and it eventually becomes more convenient to cook at home than eat out.

Food Stamped

My first year in New York City went pretty much just how I expected: a slideshow of random odd jobs (dog walking, kid schlepping, paid research studies), working for grizzly editors demanding rewrites (this does not include my wonderful book editor, Julia!), and enough bustling to warrant weekly teary breakdowns.

I didn’t, however, anticipate living way below the poverty level. My girlfriend was a full-time student (at a school we couldn’t afford), and my odd jobs barely kept my half of the rent, my own student loans, and our phone bill paid.

We applied for food stamps after a student friend of ours said we’d probably qualify. My girlfriend passed in our qualifying interview with flying colors, though she still had to show that she had a part-time job (which she did). My situation was a little trickier—I had to provide letters from the people I was freelancing for that showed a rate and number of hours per week or month. I lied and told my “clients” that I needed said letters for tax purposes (because who wants to hire a freelancer who’s on food stamps?).

We were able to do it right and apply as a household, since that’s what we are: two adults who share a fridge and three meals a day. We received a little blue credit card with my girlfriend’s picture on it and a new acronym, EBT (electronic benefit transfer). Each month $201 would appear in our online balance.

Grocery Store Game Change

As a single lass, the only relationship I’d ever shared with grocery shopping involved luxuriously selecting recipes (that involved a bunch of stuff I didn’t have in the cabinets), overbuying out of grocery store excitement, and then pitching out the decaying and compost-ready food two weeks later. When I moved to New York—and into cohabitation 2.0, grown-up edition—I no longer had the luxury of that kind of waste. (Nor should anyone, really, but that’s another story.)

With a budget of $201 to spend for an entire month’s worth of food for two people, I began to understand why my previous method wasn’t working. Like with a smart wardrobe, we needed interchangeable components in our food system.

Ditch the Recipe

Single-recipe shopping and cooking is expensive and unreasonable (unless you’re going to make that recipe every single week, as may be the case for bread or other staple recipes). Think of your dinner plate as a Trivial Pursuit game piece and break it down into components. There are three main categories that should populate your cart: greens, grains, and proteins. Here’s a list of what we regularly stock in our kitchen.

Fruits and Veggies

Usually two or three vegetable options for the week:

Collard greens

Dandelion greens

Spinach

Swiss chard

Kale

Broccoli

Snackable Fruits and Veggies

Carrots: buy the whole ones and cut them up yourself, it saves money and energy (carrots don’t grow in the snack-shape you’ll see bagged in the store)

Apples, oranges, or other fruits you can toss in your purse or bag when you’re on the go

Sugar snap peas: these are one of my fave snacky foods

While in the produce area of the store, don’t forget to grab a few staples, such as onions and garlic, and maybe carrots, tomatoes, or other veggies that you’ll use the week you buy them.

Grains

We keep grains on hand in quart-sized mason jars, which help keep them fresh by sealing out our pantry air. We keep stashes of:

Quinoa

Brown rice

Arborio rice (the rice for risotto)

Amaranth

Corn (for stovetop popping)

Buckwheat

Non-gluten-free households might also include in their grains stash:

Couscous

Barley

Farro

Bulgur

Proteins

I won’t get too high-school-nutrition-class on you here, but the healthiest diet includes various sources of protein, including lean animal proteins and hearty vegetable/grain protein complements.

Here are some ideas to get you started on diversifying your protein intake:

Beans

Tempeh

Tofu

Pastured and sustainably raised meats. (Read on in the chapter if you’re grumbling about how expensive these can be. Good meat should really be considered a special occasion supplement to a steady base of non-animal sources of protein.)

Fish, especially sardines or anchovies. I’ve learned to like them because small fish are an affordable source of omegas (best kind of fat you can get) and contain the lowest amounts of mercury contamination. Generally speaking, the larger the fish, the higher up on the food chain you’re going thus the more exposure to contaminants you’re getting.

Food in a Box?

We all have our own food preferences, and many of us have dietary restrictions. You may be vegetarian, vegan, lactose intolerant, allergic to nuts, sensitive to alcohol or carbs or sugar…the list goes on and on. In our house, we’re gluten free. For us, this ingredient omission cuts out most of the packaged, heavily processed things out there trying to pass as food.

Regardless of your diet, when you’re on a really tight budget, packaged foods are usually the first thing to go anyway, but you don’t have to be gluten free to understand why a super-long ingredients list is not good for your body. Packaged foods are generally made to endure long shelf lives (even the organic and better-ingredient versions), which means they’re often chock-full of chemicals your body can’t process. For a thorough description, I’ll defer here to Michael Pollan’s Food Rules, one of them being: if a third-grader can’t pronounce it, you probably shouldn’t be eating it.

When you attempt to make things at home, you don’t need all the additives and preservatives because you’re just going to eat it, not wrap it in plastic and drive it around the country for a month.

Word to the Wise

Don’t get grocery greedy. Remember, you can come back to the store next week (or tomorrow). You’re not stocking up for a nuclear fallout, or at least not yet. Check out Chapter 9 for details on a small-batch lifestyle.

Putting the Pieces Together

We shop to set ourselves up for success with interchangeable proteins and greens, simple stir-fry dishes, risotto combinations, and basic meat-and-potatoes kinds of meals.

We buy eggs, milk, olive oil, almond milk, raisins, nuts, coffee, spices, flour, and chocolate bars (of course) on an as-needed basis. The key to all this is planning. We make lists before going to the store, building upon what is already in the house. With the three-component system, the meal options start popping out, and the produce that’s being used up trumps (or shapes) our gastronomic whims.

Start using your fridge more as the source for what you eat each day, rather than as that big white thing collecting crumbs, grime, and rotting food (an expensive compost pile).

Food stamps taught us that we can eat well (non-GMO, mostly organics, and a lot of local or farmers’ market items) for no more than $250 a month. Let’s do some math: that’s roughly $8.33 per day for two adults. Two people can eat from home all month for what it costs to buy two mediocre lattes every day. We no longer need food stamps, but we still spend less than $300 per month on three meals a day from home, and we eat so well. Changing how we shopped was key, but here are a few places that help us (and others) keep grocery costs low.

Food co-ops. Most cities have food cooperatives in addition to regular grocery stores, and these co-ops all work a little differently in terms of benefits and requirements for membership. They often involve an initial membership fee or option to work a regular volunteer shift for reduced prices. Retail grocery prices are double, sometimes triple what stores pay. If you can join a cooperative that cuts out some of these costs in any way, do it!

Food co-ops. Most cities have food cooperatives in addition to regular grocery stores, and these co-ops all work a little differently in terms of benefits and requirements for membership. They often involve an initial membership fee or option to work a regular volunteer shift for reduced prices. Retail grocery prices are double, sometimes triple what stores pay. If you can join a cooperative that cuts out some of these costs in any way, do it!

Buying clubs. Round up a small group of friends or households to go in together on large orders—meats, vegetables, basic groceries, or hard-to-find things like canning supplies. You’ll essentially be forming your own mini co-op. Organizing and coordinating the logistics of large orders may be a learning curve at first, but when you and twenty friends (or five or six households) start saving a bunch of money, you won’t be complaining. You’ll also learn a lot about local and regional farms, companies you want to support, and what are the best deals to be had.

Buying clubs. Round up a small group of friends or households to go in together on large orders—meats, vegetables, basic groceries, or hard-to-find things like canning supplies. You’ll essentially be forming your own mini co-op. Organizing and coordinating the logistics of large orders may be a learning curve at first, but when you and twenty friends (or five or six households) start saving a bunch of money, you won’t be complaining. You’ll also learn a lot about local and regional farms, companies you want to support, and what are the best deals to be had.

Rebranded products. Places like Trader Joe’s, Aldi, Whole Foods Market, and oftentimes your local grocer rebrand products purchased from brand-name companies. Ever wonder how they can offer the low prices they tout? These stores will either make large cash purchases (a huge incentive for producers) or just exercise buying power on overstock items that companies inevitably end up producing.

Rebranded products. Places like Trader Joe’s, Aldi, Whole Foods Market, and oftentimes your local grocer rebrand products purchased from brand-name companies. Ever wonder how they can offer the low prices they tout? These stores will either make large cash purchases (a huge incentive for producers) or just exercise buying power on overstock items that companies inevitably end up producing.

The downside to all this money-saving commotion is that you don’t really know what company made whatever it is you’re buying, and you (being hip to all this) know that it’s good to know as much as possible about the things you’re buying and consuming. What you do know is that an individual store’s ethics dictate what companies/distributors it purchases from, so if you’re shopping this way, be sure you understand what your store supports. I prefer shopping for olive oil, paper products, and other higher-ticket monthly items at Whole Foods under their 365 Everyday Value brand. I understand their company policy and ethics, plus, they occasionally have overstock (and thus good prices on) humanely raised meats.

CSAs—community-supported agriculture. CSAs are available everywhere and in all sorts of forms. How it works: you “buy in” to a farm with a one-time annual payment (half or whole shares cost an average of $200 or $500, respectively) and each week during the growing season you get a box full of locally produced fruit and veggies grown on your farm. Ours works out to about $26 per week for a full-share (a huge bounty) of fruits and vegetables.

CSAs—community-supported agriculture. CSAs are available everywhere and in all sorts of forms. How it works: you “buy in” to a farm with a one-time annual payment (half or whole shares cost an average of $200 or $500, respectively) and each week during the growing season you get a box full of locally produced fruit and veggies grown on your farm. Ours works out to about $26 per week for a full-share (a huge bounty) of fruits and vegetables.

Farmers’ market deals. Contrary to popular belief, the farmers’ market is not boutique shopping. (Do you really think you’re getting the better end of the bargain for apples—or anything—that have been doused in pesticides and have traveled more than 2,000 miles to get to you?) Aside from the fact that small farmers make most of their income from direct sales at the market, market prices are usually comparable to what you’ll see at a Whole Foods or supermarket where you’d actually want to eat the produce. And farmers’ markets are hot spots for finding natural, local produce. You, the discerning, hip individual that you are, understand that image isn’t everything and that fruits or veggies that aren’t magazine-cover-worthy are not to be dismissed.

Farmers’ market deals. Contrary to popular belief, the farmers’ market is not boutique shopping. (Do you really think you’re getting the better end of the bargain for apples—or anything—that have been doused in pesticides and have traveled more than 2,000 miles to get to you?) Aside from the fact that small farmers make most of their income from direct sales at the market, market prices are usually comparable to what you’ll see at a Whole Foods or supermarket where you’d actually want to eat the produce. And farmers’ markets are hot spots for finding natural, local produce. You, the discerning, hip individual that you are, understand that image isn’t everything and that fruits or veggies that aren’t magazine-cover-worthy are not to be dismissed.

As the season is wrapping up, farmers like to unload as much of their harvest as possible. (They want to go on vacation, if they’re lucky.) As you start to tune into what’s in season—by going to the market every weekend—you’ll notice when harvest abundance flags clearance prices. Also noteworthy: farmers’ “seconds” are perfectly acceptable. My grandma grew up foraging behind supermarkets for seconds during the Depression. Farmers bring their seconds to the market but usually keep them stashed away; ask any vendor if he or she has seconds for a lower price. Slice off the bruise and dig in.

Shop around. Frugal shoppers know not only where to buy the things they need but also average price ranges for those items. You really should know what the things you buy regularly cost, and hence when a great deal is looking you in the face. Sure, this method requires trips to a few different places and actually paying attention to what you buy, but in the end it’s really worth it when you’ve saved $20 a month for a whole year. Savings add up faster than you’d expect, especially when you’re pinching pennies in the first place.

Shop around. Frugal shoppers know not only where to buy the things they need but also average price ranges for those items. You really should know what the things you buy regularly cost, and hence when a great deal is looking you in the face. Sure, this method requires trips to a few different places and actually paying attention to what you buy, but in the end it’s really worth it when you’ve saved $20 a month for a whole year. Savings add up faster than you’d expect, especially when you’re pinching pennies in the first place.

There are endless creative solutions to eating well on a budget, but they involve a little more foresight, and in some cases a little extra legwork. Can you dig it, or does that bland deli-bought sandwich really make your day?

Word to the Wise

CSAs can be an overwhelming commitment for someone not accustomed to cooking at home at least four meals a week. Even a half share will be a drastic influx of fresh produce, a ticking bomb of composting grocery anxiety. Go in on it with a committed (and, better yet, experienced) friend or roommate.

Hip Trick

Spend a few dollars on reusable cloth bags to use for grains and bulk purchases and you’ll cut packaging out of the picture entirely. These bags can usually be found near a store’s bulk section or check online.

Bulk Binge

Hit up your grocery store’s bulk bin section; if your store doesn’t have one, start shopping elsewhere. Paying by the pound for as much (or as little) as you need is the most cost-effective way to shop. Moreover, why pay someone to put something in a container that’s probably bad for the planet, anyway? Best buys in the bulk section include sugars, flours, nuts, and dry beans. And let’s not forget spices. Buying those artfully prepackaged spice containers is like stuffing money into a container of the same size and sending it off to sea. Buy small quantities of the spices called for in a recipe and stop throwing away half a container’s worth of year-old spices.

Reduce Your Convenience Consumption

Pay premiums for things like organic produce, not for easy-to-do-yourself convenience items. Stop buying:

Flavored yogurts. Plain yogurt is a perfect medium for whatever flavor you’re in the mood for. Adding a touch of maple syrup, vanilla extract, or blueberry jam (really, whatever you have on hand) is the most cost-and mood-effective way to always have a variety of flavors at your disposal.

Flavored yogurts. Plain yogurt is a perfect medium for whatever flavor you’re in the mood for. Adding a touch of maple syrup, vanilla extract, or blueberry jam (really, whatever you have on hand) is the most cost-and mood-effective way to always have a variety of flavors at your disposal.

Precut sticks of butter. Oil is usually a healthier option, but if you’re going to use butter, go for the glory here, the 32-ouncer. Surely you have a cutting board and a sharp knife. Why would you opt for someone to cut it for you? Precision is overrated; you’ll figure out how to make the pieces even enough after a few tries. I pay half the price of four sticks of pre-cut butter for the same quantity of French (translate: amazing) butter. Plus if you’re going to try clarifying butter, which I recommend, you should not buy precut sticks for this fun little chore. You’d be wasting your time and money.

Precut sticks of butter. Oil is usually a healthier option, but if you’re going to use butter, go for the glory here, the 32-ouncer. Surely you have a cutting board and a sharp knife. Why would you opt for someone to cut it for you? Precision is overrated; you’ll figure out how to make the pieces even enough after a few tries. I pay half the price of four sticks of pre-cut butter for the same quantity of French (translate: amazing) butter. Plus if you’re going to try clarifying butter, which I recommend, you should not buy precut sticks for this fun little chore. You’d be wasting your time and money.

Salad dressing. A basic vinaigrette is the simplest thing to make out of things I know you already have in the fridge and pantry. There are a ton of ways to be fancier about it, of course, but a spot of olive oil, rice or wine vinegar, salt, and pepper will give you a non-preservative-laden option for your greens.

Salad dressing. A basic vinaigrette is the simplest thing to make out of things I know you already have in the fridge and pantry. There are a ton of ways to be fancier about it, of course, but a spot of olive oil, rice or wine vinegar, salt, and pepper will give you a non-preservative-laden option for your greens.

Precut vegetables. Come on! If you’re too busy to slice up a zucchini, we gotta talk. This is most likely not even an issue because pre-cut veggies usually come on a Styrofoam tray with cling wrap, and you’ve boycotted Styrofoam (right?) because it never biodegrades. You may also be buying bagged or canned precut veggies. If so, listen up, take notes, put a Post-it on your forehead. When it comes to quantities, simple experience shows us that it’s cheaper when you buy more. No, you don’t have to go to Costco, just begin to take note of types of convenience you’re consuming, especially when buying individually packaged things. How much longer does it really take to put a few spoonfuls of yogurt in a Tupperware container?

Precut vegetables. Come on! If you’re too busy to slice up a zucchini, we gotta talk. This is most likely not even an issue because pre-cut veggies usually come on a Styrofoam tray with cling wrap, and you’ve boycotted Styrofoam (right?) because it never biodegrades. You may also be buying bagged or canned precut veggies. If so, listen up, take notes, put a Post-it on your forehead. When it comes to quantities, simple experience shows us that it’s cheaper when you buy more. No, you don’t have to go to Costco, just begin to take note of types of convenience you’re consuming, especially when buying individually packaged things. How much longer does it really take to put a few spoonfuls of yogurt in a Tupperware container?

Hip Trick

Do yourself a favor and buy the quart of yogurt and a set of small glass Tupperware containers. You’ll save money (and possibly the planet) while you’re at it.

The Grocery Shopper’s Dilemma

These are the two most basic things to keep in mind at the grocery store: understanding local and organic and why you should incorporate both into your diet. I’m not coming from the position or ideology of luxury here. We take our food (and what it ate before we eat it) very seriously.

Local. Since you’ve started your garden (Chapter 4, wink, wink) you’re getting hip to what’s in season in your area. Moreover, you’ve tasted lettuce or tomatoes you grew yourself, consuming your backyard or stoop harvest just minutes after plucking it from the ground or vine; you’re starting to see what things are really supposed to taste like.

Local. Since you’ve started your garden (Chapter 4, wink, wink) you’re getting hip to what’s in season in your area. Moreover, you’ve tasted lettuce or tomatoes you grew yourself, consuming your backyard or stoop harvest just minutes after plucking it from the ground or vine; you’re starting to see what things are really supposed to taste like.

Beyond taste, buying locally grown foods is important in reestablishing regional food systems, which strengthen local economies, cut down on travel/pollution costs and provide communities with nutrient-dense, fresh foods.

Seasonal and local are not always synonymous; for example, citrus is seasonal during winter months in the United States, yet only a handful of US states are suitable for growing citrus. Giving up lemons, limes, and oranges because you live in New York is a little extreme. It’s okay to buy Florida oranges, just know they’re in season when weather cools off and try to eat local ones then.

Buy what you can locally and make a point of sourcing things that don’t grow in your area during appropriate seasons for your surrounding regions. Hint: if it’s coming all the way from South America or Spain, it’s most likely not supposed to be in season when you’re eating it.

Organic. We try to buy mostly organic or minimally treated foods, and belonging to a food co-op helps make this affordable for us. Sadly, not everyone has that kind of option. For supermarket shoppers, meats and milk are an organic must. Industrial meat producers’ feedlot practices are enough to send you permanently to the tofu aisle. By choosing organic, you’re basically paying more money for what’s not included in your dinner: pesticides, synthetic fertilizers, genetic modifications, antibiotics, and growth hormones. But if you choose to eat meat, it’s well worth it.

Organic. We try to buy mostly organic or minimally treated foods, and belonging to a food co-op helps make this affordable for us. Sadly, not everyone has that kind of option. For supermarket shoppers, meats and milk are an organic must. Industrial meat producers’ feedlot practices are enough to send you permanently to the tofu aisle. By choosing organic, you’re basically paying more money for what’s not included in your dinner: pesticides, synthetic fertilizers, genetic modifications, antibiotics, and growth hormones. But if you choose to eat meat, it’s well worth it.

The “organic” label, like all large-scale regulatory things, is imperfect at times. Knowing as much as possible about the company touting an organic label (or about the regional farms who can’t swing organic designation because of either financial or practical obstacles) is your best bet. Marketing is slick, so cut through the fat by talking with friends and grocery store staff and checking the good ol’ interwebs.

Here’s a short list to jot down and toss into your wallet: which produce you should always buy organic, and when supplementing with conventionally grown fruits and veggies is okay. If you’re buying conventional produce, try to select a locally produced option (or at least something from your own time zone).

Must Buy Organic

Apples

Cherries

Strawberries

Peaches

Pears

Grapes (imported)

Leafy greens, like lettuce, kale, Swiss chard, and spinach

Peppers

Celery

Conventionally Grown Okay

Bananas

Blueberries

Oranges, tangerines

Avocadoes

Broccoli

Cabbage

Radishes

Onions

Sweet potatoes

Visit these online resources before you shop to further develop your grocery store glossary:

Eat Well Guide (eatwellguide.org), to figure out what’s local, in season, and sustainably produced in your area.

Eat Well Guide (eatwellguide.org), to figure out what’s local, in season, and sustainably produced in your area.

Animal Welfare Approved (animalwelfareapproved.org/consumers/food-labels), to make sense of all the different things labels will say at the store, plus understand some limitations of labeling.

Animal Welfare Approved (animalwelfareapproved.org/consumers/food-labels), to make sense of all the different things labels will say at the store, plus understand some limitations of labeling.

Buy Unsalted Butter!

- Baking and cooking often require unsalted butter because you add specific amounts of salt or salty items with other foods and don’t need extra in your butter.

- You get to choose the quality and quantity of salt when you add it. I’ll sprinkle a dash of sea salt on a piece of buttered toast for the salted butter effect, and I know I’m eating top-quality sodium.

Throes of Cooking (So you don’t Throw in the Towel)

Now, don’t panic if you haven’t set foot in your kitchen in weeks. Assume your new kitchen attitude:

- Walk into the kitchen as you would a job interview. No one needs to know that you’re nervous and insecure. All you need to project in the kitchen is confidence.

- Expect nothing to go as planned.

- Don’t rush yourself (you’ll make dumb mistakes and possibly offend anyone who walks into the kitchen). You’re not on Chopped, and times when I feel like I’m pushed to the wire always go especially terribly.

- When things don’t go as planned, figure out what you can do with what you’ve got (i.e., turn a failed omelet flip into an egg scramble—no biggie). Rarely does something emerge that’s absolutely inedible. I’ve become damn good at salvaging and transforming first attempts.

Other things to keep in mind:

Single attempts are extremely wasteful and inefficient. You bought all the ingredients to make a loaf of bread, and then never use them again; that’s the most expensive loaf of bread you’ve ever bought. On the other hand, making your own bread weekly cuts the cost factor way down since you have all ingredients on hand and now just need to supplement supplies as needed.

Single attempts are extremely wasteful and inefficient. You bought all the ingredients to make a loaf of bread, and then never use them again; that’s the most expensive loaf of bread you’ve ever bought. On the other hand, making your own bread weekly cuts the cost factor way down since you have all ingredients on hand and now just need to supplement supplies as needed.

Your success level (and thus confidence) increases when you prepare things in advance, like measuring out your ingredients, cutting your veggies, or washing the pan you’ll need in the middle of your recipe. I’m not great at timing, so high levels of preparation help keep me on track.

Your success level (and thus confidence) increases when you prepare things in advance, like measuring out your ingredients, cutting your veggies, or washing the pan you’ll need in the middle of your recipe. I’m not great at timing, so high levels of preparation help keep me on track.

You’re not alone. There are moms, dads, grandmas, friends, and a whole bunch of strangers to consult (via the interwebs). You’re likely not the only person to encounter whatever dilemma it is in which you find yourself, so reach out and use it as a sharing opportunity. Moms love getting phone calls like this—it’s an opportunity to help their grown children.

You’re not alone. There are moms, dads, grandmas, friends, and a whole bunch of strangers to consult (via the interwebs). You’re likely not the only person to encounter whatever dilemma it is in which you find yourself, so reach out and use it as a sharing opportunity. Moms love getting phone calls like this—it’s an opportunity to help their grown children.

Give yourself a break. Phase into cooking at home slowly so that a routine shakes out. You’re likely to succeed by small, repetitive attempts, not by changing the way you’ve lived until now in a single day.

Give yourself a break. Phase into cooking at home slowly so that a routine shakes out. You’re likely to succeed by small, repetitive attempts, not by changing the way you’ve lived until now in a single day.

Phase 1: Start Your Day

Make coffee at home. In eight out of ten cases, you’re paying a premium for crappy beans prepared an hour or two in advance, double gross. If you like coffee, not just the idea of coffee (flavored latte, Frappuccino, etc.), set yourself up for home-caffeinated success.

Buy decent beans. This remains the most surefire way to make your own good cup of joe. Paying $10–$15 for a pound of coffee, which will last you for two weeks, is not highway robbery. You’re paying $11 a week for a few basic cups of drip coffee in any coffeehouse. If you’re truly serious about your cup, look for artisanal roasters who practice direct trade—Stumptown, Intelligentsia, and Counter Culture are great and are available across the country. Remember that a fair trade label guarantees only wages, not bean quality. I don’t usually like the mainstream organic/fair trade beans (that’s right, I’m a coffee snob, I’ll admit it). Give a couple alternative blends a try; you’ll find the right ones for your taste buds.

Buy decent beans. This remains the most surefire way to make your own good cup of joe. Paying $10–$15 for a pound of coffee, which will last you for two weeks, is not highway robbery. You’re paying $11 a week for a few basic cups of drip coffee in any coffeehouse. If you’re truly serious about your cup, look for artisanal roasters who practice direct trade—Stumptown, Intelligentsia, and Counter Culture are great and are available across the country. Remember that a fair trade label guarantees only wages, not bean quality. I don’t usually like the mainstream organic/fair trade beans (that’s right, I’m a coffee snob, I’ll admit it). Give a couple alternative blends a try; you’ll find the right ones for your taste buds.

Get a grinder. Don’t grind all the beans in advance at the coffeeshop or store; that drains off the freshness and is usually the reason why your coffee at home doesn’t taste the same. The aromatic flavor that makes or breaks your coffee starts to go stale the minute you grind it. If your shitty beans don’t kill it, pregrinding will.

Get a grinder. Don’t grind all the beans in advance at the coffeeshop or store; that drains off the freshness and is usually the reason why your coffee at home doesn’t taste the same. The aromatic flavor that makes or breaks your coffee starts to go stale the minute you grind it. If your shitty beans don’t kill it, pregrinding will.

Brew with low or no technology via the pour-over method or a French press. You don’t need a fancy coffeemaker to enjoy coffeehouse-style cups of coffee every morning.

Brew with low or no technology via the pour-over method or a French press. You don’t need a fancy coffeemaker to enjoy coffeehouse-style cups of coffee every morning.

If you insist on spending money (or brewing espresso), buy a $100-plus grinder before you invest in other coffee technology. Though we haven’t graduated to that level of grind snobbery yet, we still enjoy fine French-press coffee using our small Krups grinder.

Now, for food: what do you eat for breakfast? Think in terms of fuel and grams of protein, the goal for this meal being 15. Keep up the spirit of the Trivial Pursuit game, with extra points for something green for breakfast.

There are all sorts of things you can mix and match in the morning to get you going: eggs, granola (the homemade kind is a fun project), yogurt and cereal, black beans and grits, garden veggies or greens sautéed and served with leftover quinoa from last night’s dinner, breakfast tacos, turkey or tofu sausage. The possibilities are endless. Always have a couple options on hand because breakfast monotony is a tedious way to start your day.

Hip Trick

If fancy weekend breakfast projects like pancakes, French toast, or biscuits sound intimidating, try starting out with mixes (pancakes, bread, etc.) to get yourself into the routine.

Once it’s normal to be making Sunday brunch at home, expand your experience with made-from-scratch foods.

Phase 2: Are Those Dinner Bells?

The momentum builds when you cook at least three dinners at home in a week: your groceries are connected immediately to cooking, which seems like a silly, redundant thing to say, but it’s a sad reality that so many times groceries just sit in the fridge as components of meals never made.

Solutions:

Breakfast for dinner. Why not? You already have breakfast down, so ritualize omelet or pancake night to shake things up in the evening.

Breakfast for dinner. Why not? You already have breakfast down, so ritualize omelet or pancake night to shake things up in the evening.

Learn some kitchen basics. It can be from your mom, Netflix (The French Chef episodes), YouTube, or whatever, and repeat often. Practice sauté skills, chopping like you mean it, how to poach an egg, whatever eludes you. Adding skills to your kitchen artillery will only give you more options on a night when you’re tired and hungry.

Learn some kitchen basics. It can be from your mom, Netflix (The French Chef episodes), YouTube, or whatever, and repeat often. Practice sauté skills, chopping like you mean it, how to poach an egg, whatever eludes you. Adding skills to your kitchen artillery will only give you more options on a night when you’re tired and hungry.

Always make more than you’ll eat in one sitting. This goes for whether you’re cooking for yourself or for a whole household. The super-cool thing about making dinner at home is that you’ve got lunch tomorrow (and maybe extra meals) as an added incentive. Two meals for one night’s effort; this is big.

Always make more than you’ll eat in one sitting. This goes for whether you’re cooking for yourself or for a whole household. The super-cool thing about making dinner at home is that you’ve got lunch tomorrow (and maybe extra meals) as an added incentive. Two meals for one night’s effort; this is big.

Beyond practicality, cooking at home means you know exactly what you’re putting in your body, a luxury not afforded by restaurant cooking. If you’re shopping smartly, you know where your vegetables came from, how they were grown, what didn’t get injected into your meat. We can’t afford to eat regularly at restaurants that pride themselves on that quality (and knowledge about their) fare.

Phase 3: Experiment with DIY Staples

Celebrate your graduation to becoming comfortable using the kitchen by making something that seems fancy. Baking bread is a good example of something you might try to do yourself, but these staples could be any food you buy regularly that probably isn’t all that hard to make. Vanilla ice cream has been a fun homemade infusion on our dessert table. See the list at the end of this chapter for more made-from-scratch food inspiration ideas and a bread-from-scratch how-to.

Your Kitchen Toolbox:

Where to Spend Your Money

A good knife. A heavy-duty 8-inch chef’s knife is the only knife a serious (new) home cook needs to have. The only thing that really matters about your knife is that it feels comfortable and stable in your hand and that it’s really sharp (cheap or dull blades are more dangerous since you have to use more force). Expand upon your slicing and dicing repertoire after you know what your real needs are. Are you cutting homemade bread? Are you paring fruit? A note on cost: it’s going to run you about $100 if you just go buy it, but sale options are available. I got mine at half off since Wüsthof discontinued the series (the 4587 Grand Prix model). You will need to buy a $30–$40 sharpening steel after a year’s worth of consistent use with any knife.

A good knife. A heavy-duty 8-inch chef’s knife is the only knife a serious (new) home cook needs to have. The only thing that really matters about your knife is that it feels comfortable and stable in your hand and that it’s really sharp (cheap or dull blades are more dangerous since you have to use more force). Expand upon your slicing and dicing repertoire after you know what your real needs are. Are you cutting homemade bread? Are you paring fruit? A note on cost: it’s going to run you about $100 if you just go buy it, but sale options are available. I got mine at half off since Wüsthof discontinued the series (the 4587 Grand Prix model). You will need to buy a $30–$40 sharpening steel after a year’s worth of consistent use with any knife.

Rubbermaid high-heat spatula/scraper. It’s white with a red, nylon handle. Buy it online because I’ve only seen it in stores for $26 (which is less money than you’ll pay for dinner for two when you’re cooking, by the way). You will use it for everything; I have both the 9.5-inch and 13.5-inch handle lengths and one (or both) is always lurking in my dish-drying rack.

Rubbermaid high-heat spatula/scraper. It’s white with a red, nylon handle. Buy it online because I’ve only seen it in stores for $26 (which is less money than you’ll pay for dinner for two when you’re cooking, by the way). You will use it for everything; I have both the 9.5-inch and 13.5-inch handle lengths and one (or both) is always lurking in my dish-drying rack.

Cutting board. Get at least one that’s not a pain in the ass to lug out and clean (translate: not gigantic).

Cutting board. Get at least one that’s not a pain in the ass to lug out and clean (translate: not gigantic).

A good 10-or 12-inch sauté pan. I’m anti-nonstick (not down with heating a chemical coating to toxic off-gassing point every day), but do as you please in your house. (Nonstick households have fewer options with cooking tools because you can’t use most of your metal utensils on those pots and pans. Teflon flakes in the risotto? No thanks.) I know you have the basic pots and pans, but the great thing about this specific pan is that mostly any meal made in our house can be made in it. As for brand, ours is the 3-quart Calphalon Tri-Ply 18/10 stainless-steel model. It’s all metal and can go directly in the oven, which makes it a versatile tool.

A good 10-or 12-inch sauté pan. I’m anti-nonstick (not down with heating a chemical coating to toxic off-gassing point every day), but do as you please in your house. (Nonstick households have fewer options with cooking tools because you can’t use most of your metal utensils on those pots and pans. Teflon flakes in the risotto? No thanks.) I know you have the basic pots and pans, but the great thing about this specific pan is that mostly any meal made in our house can be made in it. As for brand, ours is the 3-quart Calphalon Tri-Ply 18/10 stainless-steel model. It’s all metal and can go directly in the oven, which makes it a versatile tool.

Two mixing bowls (large-and medium-sized).

Two mixing bowls (large-and medium-sized).

A wooden spoon or two.

A wooden spoon or two.

Upgrades to make as you can afford them (or find at thrift stores or flea markets):

A wire mesh strainer. I still don’t have one, and I kick myself every time I make broth, stock, or jelly.

A wire mesh strainer. I still don’t have one, and I kick myself every time I make broth, stock, or jelly.

Cooling rack (for bread, cookies, etc.). After a long time using makeshift cooling racks, this was a super-luxurious addition to my kitchen (for a mere $15).

Cooling rack (for bread, cookies, etc.). After a long time using makeshift cooling racks, this was a super-luxurious addition to my kitchen (for a mere $15).

Kitchen scale. Surprisingly useful, especially in fancier recipes where they call for the weights of ingredients. Recipes using weight also, not surprisingly, tend to have lower failure rates.

Kitchen scale. Surprisingly useful, especially in fancier recipes where they call for the weights of ingredients. Recipes using weight also, not surprisingly, tend to have lower failure rates.

A set of stainless-steel measuring cups. These are great if precision matters to you. I still don’t own a set, though a 1/3 cup measure would be really helpful.

A set of stainless-steel measuring cups. These are great if precision matters to you. I still don’t own a set, though a 1/3 cup measure would be really helpful.

Anything Le Creuset. Well made, impossible to break, allows food to cook more evenly, and super-versatile in action. Not to mention gorgeous pieces you’ll love and treasure forever.

Anything Le Creuset. Well made, impossible to break, allows food to cook more evenly, and super-versatile in action. Not to mention gorgeous pieces you’ll love and treasure forever.

A food mill. If you find yourself jone-sing to make applesauce in the fall.

A food mill. If you find yourself jone-sing to make applesauce in the fall.

Useless fancy tools, stuff you don’t need to buy (even though recipes say you do):

Flour sifter. Use a whisk instead (and the sifter is a complete pain in the ass to clean, by the way).

Flour sifter. Use a whisk instead (and the sifter is a complete pain in the ass to clean, by the way).

Garlic press.

Garlic press.

Mandoline. Don’t get one if you are interested in keeping your fingers.

Mandoline. Don’t get one if you are interested in keeping your fingers.

Mini food processor. Go for the big one, or don’t get one at all.

Mini food processor. Go for the big one, or don’t get one at all.

Meat tenderizer.

Meat tenderizer.

Stuck on How to Transition your Household Away from Nonstick?

I love these smart, simple tips from the book Slow Death by Rubber Duck: The Secret Danger of Everyday Things for prying yourself from reliance upon the off-gassing nonstick cookware:

- Buy a decent skillet/sauté pan. Good choices include cast iron, stainless steel, and enamel-coated cast iron.

- Use enough oil to coat the surface.

- Wait until pan is hot to place food in it.

- Use a metal spatula (not plastic).

Mis En Place

This French term you’ve probably heard on cooking shows describes the best of intentions, to have all your ingredients gathered and ready in advance.

While this may be crucial for industry chefs, home cooks (like me) might find dinner prep easier (and use considerably less dishes) by preparing as you go. I decide to do this or not do this depending on my mood and time constraints.

Cookbooks and Following Recipes

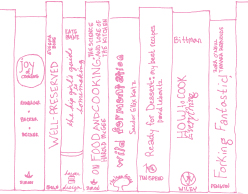

I used to collect cookbooks because I thought that’s what every cook should have, a big library of references and resources. Then I realized that in two years, I hadn’t once opened the cookbook cabinet in my single-lady household. I finally realized what the issue was: I’m not good at following recipes.

Cookbooks are super-personal possessions. Any one you actually look in is worth three on the shelf just sitting collecting dust. Prioritize and get acquainted with one cookbook to get yourself started. I accidentally fell in love with The Joy of Cooking on a night I couldn’t get hold of my mom to ask about cooking temperatures for meats in the middle of dinner preparations. As I flipped through the various sections—meats, vegetables, yeast breads, etc. (all of which are introduced by an overview of methods and useful information)—I discovered Irma’s signature recipe formatting (bold print), ingredients in-line with the steps of the preparation method at the spot in which you use them. Who knew a little cut-and-paste action could change my recipe-phobic world entirely: how much you need plus what to do with the ingredient, all in the same place!

I asked my blog readers for the one cookbook they’d choose in a desert island scenario (assuming you had a grocery store on your desert island), and here’s what they said:

Never buy a cookbook before actually perusing it beforehand (either online or at the library) since all recipe authors’ styles vary; find the ones you understand and follow most easily. When it comes to buying used copies, any cookbook with Grandma’s handwritten notes or recipe cards stashed inside instantly makes my cut, too!

BASICS:

The Joy of Cooking (of course)

The Way to Cook by Julia Child

Simple Cooking by Alice Waters

The Best Recipe by the editors of Cooks Illustrated

Master Recipes by Stephen Schmidt

The Naked Chef Takes Off by Jamie Oliver

The New York Times Cookbook by Craig Claiborne

Better Homes and Gardens New Cookbook, 11th edition

Ad Hoc at Home by Thomas Keller

How to Cook Everything by Mark Bittman

VEGGIE-STYLE (NOT ONLY FOR VEGETARIANS):

The Modern Vegetarian Kitchen by Peter Berley Moosewood Restaurant Cooks at Home by the Moosewood Collective

Vegetarian Cooking for Everyone by Deborah Madison

How to Cook Everything Vegetarian by Mark Bittman

Word to the Wise

Newer editions of cookbooks are not always better. I’ve hoarded a small collection of older editions of The Joy of Cooking, since someone thought homemade ice cream and canning and preserving was outdated information around 1970.

The Kitchen Ecosystem

“Once you get used to having homemade mayonnaise in the fridge there is no going back to Hellmann’s,” explains author and savvy chef Eugenia Bone in her Denver Post blog, Preserved (blogs.denverpost.com/preserved). She coined the term “kitchen ecosystem,” and I was lucky enough to spend an enchanted afternoon with her discussing all things kitchen, including efficiency and the small-batch model as well as canning and preserving issues. The more she elaborated on how the kitchen is an actual ecosystem, with food in all stages of life and functionality, the more I realized that this is basically permaculture for your kitchen, and any smart, frugal person using common sense will arrive here on her own. Close the loop on wastes, utilize all assets (and forms of food), and insert homemade things as you go (because they’re not that hard to make).

Things I love about the kitchen ecosystem:

It’s firmly based in reality, and not theoretical. Your fridge right now, as is, comprises your ecosystem. You’re not working toward anything. You’re operating in the everyday realm, making improvements and adding depth as you go.

It’s firmly based in reality, and not theoretical. Your fridge right now, as is, comprises your ecosystem. You’re not working toward anything. You’re operating in the everyday realm, making improvements and adding depth as you go.

Momentum. The more you do yourself, from scratch, the more normal that approach becomes. We’re so programmed to think that from scratch is harder and thoughtless convenience is better.

Momentum. The more you do yourself, from scratch, the more normal that approach becomes. We’re so programmed to think that from scratch is harder and thoughtless convenience is better.

Having items at “varying stages of utility” in the fridge is an impetus for innovative meal planning and creation. This is true even for people like me who are actually intimidated by everyday cooking and sustenance.

Having items at “varying stages of utility” in the fridge is an impetus for innovative meal planning and creation. This is true even for people like me who are actually intimidated by everyday cooking and sustenance.

The possibilities are endless, and they’re full of common sense. It’s exciting to watch areas of your kitchen unfold with opportunity, such as seeing how to stop stressing over not using groceries how you’d anticipated using them. There are always other ways to extend the life of fresh ingredients or transform marginally good ones into an amazing sauce or soup.

I love this ecosystem idea because it gets to the heart of the matter. As Eugenia wrote, “Thrifty prepping and cooking can get you ahead of the dinner curve in ways that are delicious, conscientious, and uncomplicated.”

Getting the Most Out of Your Kitchen Ecosystem

- Make stocks from scraps and trimmings. Whip up small batches that you can use within three days, or freeze.

- Buy and roast a whole chicken. This creates many meals, the stock for a soup, and bones for another broth.

- Freeze or preserve fruit you’re not going to eat in its prime. Use it in pancakes or muffins.

- Make breadcrumbs from stale bread. Toss the bread in the food processor and freeze the crumbs until needed in a recipe.

- Make your own condiments (mayonnaise, vinaigrette, jams, horseradish, etc.). Not only will you fork over less at the store, but you’ll be putting better-quality components in your system.

AP Credit: Scratch Foods

Adding homemade things to your kitchen ecosystem is not only a way to develop richer flavors in meals but also the way to really utilize what you’ve got. Depending on the tools at hand, the following lists show my favorite things to try doing yourself at least twice (or twelve times), all of which I’ve managed as a novice. Required tools: just the basic kitchen essentials.

Bread. A weekly task that impresses the pants off everyone who comes in contact with your table.

Bread. A weekly task that impresses the pants off everyone who comes in contact with your table.

Stovetop popcorn. Makes you feel like a genius for thwarting the microwave and those handy (and toxic) perfluorocarbon-coated popping bags.

Stovetop popcorn. Makes you feel like a genius for thwarting the microwave and those handy (and toxic) perfluorocarbon-coated popping bags.

Chicken (or vegetable) stock from kitchen scraps. Inflates your Depression-era-granny ego for making good use of trash (and makes cooking rice the next day flippin’ fantastic).

Chicken (or vegetable) stock from kitchen scraps. Inflates your Depression-era-granny ego for making good use of trash (and makes cooking rice the next day flippin’ fantastic).

Clarified butter. The single most important thing that has happened to my kitchen thus far. (I suspect mayonnaise will be the next breakthrough.)

Clarified butter. The single most important thing that has happened to my kitchen thus far. (I suspect mayonnaise will be the next breakthrough.)

Pancakes/muffins. Pancakes remain the best and most impressive brunch-hosting tool ever, and muffins are a quick way to infuse some homemade snack-age into your life.

Pancakes/muffins. Pancakes remain the best and most impressive brunch-hosting tool ever, and muffins are a quick way to infuse some homemade snack-age into your life.

Tortillas. Turning your house into a tortilleria once in a while makes for bad-ass taco nights or (bonus!) fry up your tortillas into chips. It’s the most useful way to rid the fridge of aging tortillas and quell a chips-and-salsa addiction at the same time.

Tortillas. Turning your house into a tortilleria once in a while makes for bad-ass taco nights or (bonus!) fry up your tortillas into chips. It’s the most useful way to rid the fridge of aging tortillas and quell a chips-and-salsa addiction at the same time.

Make whipped cream. Pour ½ cup heavy or whipping cream, 1 teaspoon powdered sugar, and a few drops of vanilla extract into a cereal bowl and whisk for a few minutes. You’ll thank me when you’re dolloping the perfect amount of whipped cream on top of yummy summer fruit (or licking the whisk).

Make whipped cream. Pour ½ cup heavy or whipping cream, 1 teaspoon powdered sugar, and a few drops of vanilla extract into a cereal bowl and whisk for a few minutes. You’ll thank me when you’re dolloping the perfect amount of whipped cream on top of yummy summer fruit (or licking the whisk).

Helpful tool: a good food processor (e.g., a big Cuisinart one or something similar).

Among the things you can make with it:

Salsa

Salsa

Smooth soups (like gazpacho or potato leek)

Smooth soups (like gazpacho or potato leek)

Hummus

Hummus

Pesto

Pesto

Pizza dough (fun in the food processor, but works like a charm when hand-kneaded like bread)

Pizza dough (fun in the food processor, but works like a charm when hand-kneaded like bread)

Pastry dough

Pastry dough

Baby food (or plain vegetable purees you can freeze in ice-cube trays for infusing sauces or baked goods)

Baby food (or plain vegetable purees you can freeze in ice-cube trays for infusing sauces or baked goods)

Another helpful tool: a fancy stand mixer (e.g., the Kitchen Aid you received on account of your wedding registry and don’t really know what to use it for). It’s great for:

Frosting or larger batches of whipped cream

Frosting or larger batches of whipped cream

Cakes (and cupcakes)

Cakes (and cupcakes)

Cookies

Cookies

Ice cream (with the ice cream maker attachment; it’s the best $50 you’ll ever spend)

Ice cream (with the ice cream maker attachment; it’s the best $50 you’ll ever spend)

Hip Trick

Keep a kitchen journal. It helps to not only keep track of what you succeed (and fail) at in the kitchen, but also to keep all those things in one place. I keep a small, bound journal and write down ingredient amounts, any improvisations, how much food the recipe made and notes for future attempts. Use a three-ring binder if you like to keep recipes and experiences in an order other than chronological.

Breadwinners Can Be Bread Makers Too

So I’ll admit it: bread making was a stretch, even for me. I didn’t really believe in myself, and more important, I liked believing that bread was too tough for me. I was a hard sell until I met an actual dough ball. It was smooshy and stretchy and let me pound and squish and thud out animosities surrounding the Metropolitan Transit Authority or my astonishment at being pelted on the forehead by a seven-year-old with a tangerine. Somewhere between this little yoga workout and the yeast awakening (hellooo, dough puff!) I was sold. I can bake bread from scratch.

This might be something your grandma and maybe even your mom did. My store-bought-bread upbringing never really put me in touch with my bread history (my ancestors and their propensities (or aversions) for making bread) nor with my surprising proximity to traditions of bread from scratch.

After looking at too many books and online recipes, I discovered and adapted a recipe that fit two criteria (and my life):

- It didn’t intimidate me as a beginning baker.

- It featured nutritious ingredients found in regular home kitchens (but not too many ingredients).

Simple first, fancy later.

Homemade Bread for Busy People

I know what you’re thinking: you have a job, maybe kids, and 237 more pressing things to do than knock off two evenings for bread making. These are more like snippets of evenings, not entire evenings. Hear me out: if I can do this and not hate it, then you can too. If you give it a shot, it will be totally worth it.

Let’s talk about the benefits of making bread for a minute:

There is no one right way to make bread. It’s pretty hard to mess it up, and if you do, a toaster and some jam usually fixes the problem.

There is no one right way to make bread. It’s pretty hard to mess it up, and if you do, a toaster and some jam usually fixes the problem.

You don’t need any fancy supplies or expensive equipment. Nope, not even a mixer.

You don’t need any fancy supplies or expensive equipment. Nope, not even a mixer.

The slow-rise (arguably best-tasting) method is actually most convenient for busy people.

The slow-rise (arguably best-tasting) method is actually most convenient for busy people.

Kneading and working with dough is an incredibly satisfying, stress-relieving activity after a long day’s work (in nearly all professions, except for maybe bakers).

Kneading and working with dough is an incredibly satisfying, stress-relieving activity after a long day’s work (in nearly all professions, except for maybe bakers).

Making your own bread is cheaper than purchasing bread of the same nutritional value, and you can avoid all the preservatives and junk in most store-bought bread.

Making your own bread is cheaper than purchasing bread of the same nutritional value, and you can avoid all the preservatives and junk in most store-bought bread.

You get free air freshener by baking at home!

You get free air freshener by baking at home!

Even You Can Make Bread

So, I’ll admit it, when I first began to make my own bread it was a stretch, even for me. I didn’t really believe in myself and, more important, I liked believing that bread was too tough for me. I was a hard sell, until I met an actual dough ball.

It was smooshy and stretchy and let me pound and squish and thud out animosities surrounding the Metropolitan Transit Authority or my astonishment at being pelted on the forehead with an old tangerine by a seven-year-old. Somewhere between this little arm workout and the yeast awakening (hellooo, dough puff!) I was sold. I can bake bread from scratch.

This might be something your grandma and maybe even your mom did. My store-bought wheat bread upbringing never really put me in touch with my bread history—my ancestors and their propensities (or aversions) for making bread—nor my surprising proximity to traditions of making bread from scratch.

There are no less than 500 ways to make the same thing (bread), so I don’t blame you for feeling overwhelmed by the prospect. Visit the Hip Girl’s Guide to Homemaking blog for my tried-and-true recipes and methods for simple honey wheat sandwich bread or my signature gluten-free millet oat bread for both oven and bread machine preparation.

But first, here’s a quick rundown on the ins and outs of bread. Bread may seem like a lot of steps at first, but as you become familiar with the phases, you’ll be able to fold it into your routine.

Eight Fun Things you can do with a Loaf of Your Homemade Bread

- Eat all of it immediately.

- Invite friends to your house for a tea party, where you chat with mouths full of cucumber sandwiches on homemade deliciousness.

- Send a loaf to your granny, who loves getting packages and quite likely doesn’t bother with the “hassle” of fresh loaves any longer.

- Make caprese bites (or some other zesty little appetizer) and bring them to a dinner party or potluck.

- Bring freshly baked bread to new friends who showed you how to do something. I brought a hunk of crusty wonderfulness as a gesture of thanks to friends who showed me how to can tomatoes. Tit for tat.

- Take a loaf to your new neighbors. Get tight with the people who live on top of, beside, or below you.

- Bread makes a perfect gift for people going through times of transition: births, deaths, surgeries, and everything in between. Everyone’s gotta eat; why not provide fresh warm bread?

- Kick-ass French toast. ’Nuff said.

Yeast Breads

When you bake bread, most recipes call for yeast. (Quick breads are those recipes that utilize baking soda and/or powder instead of yeast to puff up the dough.)

Active dry yeast is the most common kind you’ll probably use and it comes in packet form for easy portioning. This kind of yeast needs water and a little bit of sugar to activate. The cool thing about mastering yeast is that once you get it, you’ll gain access to other cool homemade projects like bagels, pizza dough, and doughnuts!

Wet vs. Dry Ingredients

Usually you’ll combine wet and dry ingredients in separate bowls and then gradually add the dry to the wet to form your dough. This ensures an even distribution of ingredients.

Knead

Kneading your dough allows the flour to develop its gluten “muscle” strength. As you work your dough, it will become stretchy and more elastic—a perfect shell to house millions of yeast-produced carbon dioxide pockets. Yum. Gluten-free breads will develop their elasticity in the mixer or in your mixing bowl.

Kneading is easy. There’s a little method involved, but you may personalize your kneading style as you get more practice. Tips for easy kneading:

- Dust a little flour on a clean countertop. Flatten your dough with the heel of your hands (lower palms) and then fold the dough over itself (like a taco).

- Work it flat again and then rotate the flat pancake a quarter turn and repeat the taco roll and flatten again.

- Every now and then pick the dough up and slam it down on the counter with a big whack!

Hip Trick

You can always double a bread recipe by following it through the first rise and then sticking extra dough balls in the fridge for quick homemade bread during the next month. Don’t forget to date your dough bags.

To defrost, just place the balls in the fridge until thawed and then follow your recipe’s instructions for the second rise.

Rise

Most yeast breads need two opportunities to rise, one to develop gluten strength fully, and the other to prepare the bread for baking. Gluten-free bread bakers need only provide one rise since alternative grains’ protein molecules behave differently from those of wheat.

By the time this stage appears you have a pile of dirty dishes (a mixing bowl and measuring cups and spoons) staring at you from the sink. I only have one large mixing bowl, so at this point I have to wash it. Don’t forget to grease the bowl before you set dough in for the rise. (I learned this lesson the hard way!)

For best rise results, cover dough with a slightly damp tea towel or greased plastic wrap and stick the loaf pans in a cool oven, keeping the oven off. The pilot light (if you have a gas oven) creates the perfect temp for the final rise. (My house is chilly in the winter and the open countertop doesn’t work well for the final rise.) If your house is not gas powered, turn the oven on, let it reach 200°F and then turn it off. Stick the dough ball in after the oven has been off for at least 10 minutes.

For those of you with instructions for two rises, the second one happens in the loaf pan or in whatever baking medium you choose. You’ll punch down the dough, place it in the pans and get it ready to bake by leaving it alone for a while. Lots of breaks mean you can accomplish other things during your bread-making session.

Bake

Ovens vary in temperature and heating patterns, so rotating your loaf pans midway through the baking time will ensure the loaves are cooked uniformly.

To test for doneness, I stick my thermometer in the corner of the near-finished loaf just to be sure my oven hasn’t gone wild. Take the loaves out when the thermometer reads 200–205 degrees internally. Drop your loaves out of the pans immediately and place them to cool on the rack. Note the hollow sound when you tap the bottom of the loaves as this is another sign of doneness.

The Perfect Crust

My first few loaves left a lot to be desired in the crust category. Here are a couple ways to darken your crust:

- Place a small (oven-safe) pot or pan on the bottom rack of the oven before turning it on and then add one cup of water three minutes before you put your loaf in to bake. Be extremely careful; the initial steam produced by pouring in the water can burn you!

- Brush the loaf top with melted butter or a well-whisked egg.

Hip Trick

My favorite way to store homemade bread is wrapped in waxed paper as tightly as you can manage and leave it on the counter. We tie our loaves up with kitchen twine for easy access and resealing capabilities.

The fridge dries out bread fast, so avoid keeping it in there.

First-Timer Tips

It’s important to make baking special, not stressful. Here are a few tips and words of advice for you to keep in mind:

- Though any day will do in the future; give yourself some room on the first attempt. Select a day where you’re not in a time crunch, perhaps a lazy weekend afternoon.

- Phone a friend. Said friend does not actually have to be involved in the baking process, but you need a warm body in the room. This person will be invaluable in helping you to not take yourself so seriously and keeping flour out of the computer keyboard if you’re following an online recipe.

- Read the recipe all the way through before you start. Map out the waiting periods and determine if you have enough time from start to finish. You don’t want to be up until 2:30 a.m. waiting to pull your loaves out of the oven, trust me.

- Recipes are meant to be broken. I’m directions-phobic; give me a set of instructions and I’ll start devising a way of altering or avoiding them. Give yourself some room to interpret one person’s method into one that works well for you.

- Clean and sanitize your countertop before getting started so you don’t have to worry about it while you’re elbow deep in flour and transitioning from mixing to kneading.

- Don’t try to knead your dough on a cutting board, no matter the size or material. Unless your board has industrial-strength suction cups, you’ll end up frustrated.

- Make tea (or margaritas) to make it official; a drink of some sort helps you remember that you are having fun. A pretty apron helps too.

- Don’t cut the finished product until it has cooled completely (approximately 40 minutes) since it is still developing flavor in the cooling process.

- Relax! Don’t give yourself a hard time about perfection. So, your first shot didn’t place you in the running for the best up-and-coming artisan baker awards. Bread making begs you to simply live and learn. It’s really hard to make bread that’s entirely inedible. After all, dense bread still tastes like homemade bread, and makes a pretty kick-ass French toast.

Resources

Books

The Omnivore’s Dilemma by Michael Pollan.

The Omnivore’s Dilemma by Michael Pollan.

Will change the way you view food and wandering around the grocery store.

Something from the Oven by Laura Shapiro.

Something from the Oven by Laura Shapiro.

Covers the rise of the food industry, why popular food became so gross in the 1950s, roles of women and domesticity, feminism, and general inspiration.

On Food and Cooking by Harold McGee.

On Food and Cooking by Harold McGee.

Demystifies chemical and physical properties of food and helps you understand why certain things behave the way they do in the kitchen.

The Sharing Solution: How to Save Money, Simplify Your Life and Build Community by Janelle Orsi and Emily Doskow.

The Sharing Solution: How to Save Money, Simplify Your Life and Build Community by Janelle Orsi and Emily Doskow.

Will help you start a buying club or think up other ways to collectively save money on food with your neighbors, friends, or community.

Web

localharvest.org

localharvest.org

Find local farmers’ markets, nearby CSAs, and real food resources