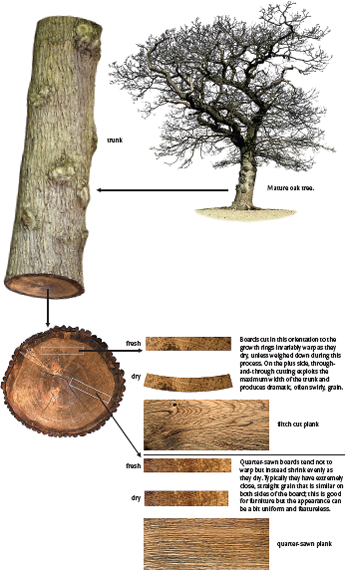

In the past, an oak tree was so valuable that, when felled, almost every part was of commercial value. The bark was used in tanning, slender branches became calorific firewood and arching main side branches became important supporting struts in building construction. But it was the main trunk that held the greatest significance and to this day a felled oak is cut up as a source of valuable timber. To the uninitiated, sourcing planks and beams from a trunk may seem a straightforward affair. However, this is not the case; the way in which a trunk is sawn can have an important effect upon the way the resulting timber behaves subsequently.

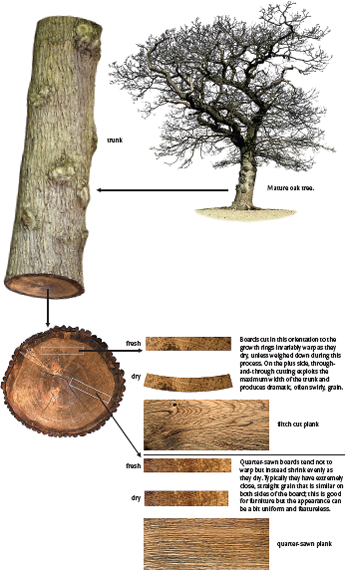

The orientation of saw cuts in relation to the growth rings of the tree has the most profound effect upon the subsequent timber. Today, sawmills typically want to maximise the yield from any given trunk and rotate it during the cutting process. More traditional approaches either cut the wood through-and-through in parallel cuts, a method referred to as flitch cutting, or quarter-saw it, where the trunk is divided into quarters and each quarter cut radially to the growth rings. Planks that are cut at right angles to the grain, as happens with much flitch-cut timber, behave differently from quarter-sawn planks as the wood dries out and shrinks.

There are few finer testaments to the strength and durability of oak than the timber-framed Great Barn, in Old Basing, Hampshire. The main timbers came from oaks felled in 1534. The curved side supports would have come straight from the side branches of oaks such as the one on the facing page.