Although there are many tracts of forest in the British Isles that harbour native species and ancient trees, it is important to realise that almost no woodland in Britain and Ireland can be described as truly virgin and untouched. For millennia man has interfered with the forested landscape, cutting down trees for fuel and building materials, and in order to create agricultural land. Some types of woodland are more modified than others and a few exist entirely as a result of human actions. However, when it comes to woodland comprising native species, the history of use does not necessarily detract from its ecological importance and value to wildlife; on the contrary, it often enhances it. Of greater significance than the age of the trees in a given area is a continuity of woodland cover. Many woodlands have had continuous tree cover since before man first settled the land and the diversity of associated wildlife reflects this venerable ancestry. The fact that ecologists refer to most British and Irish woodland as semi-natural is in no way derogatory.

Almost all the oak trees in Bramley Frith, Hampshire, are just a few hundred years old; much older ones were blown down in the Great Storm of 1703. Nevertheless, the woodland has had continuous tree cover since at least the Domesday Book.

Even as solitary individuals, native tree species will harbour a good array of wildlife. However, it is when they grow alongside and among other trees, and form woodland, that their true ecological potential becomes apparent. This can be thought of as synergy, if you like: from a wildlife perspective the whole (the woodland) is greater than the sum of the parts (the trees).

Walk through an area of recently planted woodland and you will usually discover a mixture of tree species, comprising individuals of different ages. However, visit ancient semi-natural woodland and typically you will find that one or two tree species predominate, either because environmental conditions favour them or because they have been encouraged by man. Although these woodlands do not qualify as habitats in the strict sense (ecologists refer to them as vegetation types), some of them are easily recognised and, more significantly, have a classic set of woodland animals, plants and fungi associated with them.

Professional ecologists recognise a large number of subtly different vegetation types and use them to define the natural history of the British and Irish landscape. However, for most people the differences between many of these types are too subtle to discern and most are happy to make reference to just a handful of easily recognised woodland types. The descriptions that follow cover the more distinctive, widespread and easily recognised of these communities.

The Pedunculate Oak is one of the most common large native tree species across much of central and southern England, and in many woodlands it dominates in terms of stature and tree canopy cover. In some areas, its prevalence may be the result of soil conditions favouring its growth over other species. However, in many instances, an examination of the woodland structure and history will reveal man’s contribution to the equation. If, for example, a particular woodland has oaks all of a similar size, then even if they are old their presence and dominance is likely to be the result of planting, in earlier centuries, and of selective felling of other species. This is hardly surprising because oak has always been considered the construction timber of choice. In such circumstances, mature oaks are referred to as standards.

In many semi-natural Pedunculate Oak woodlands you will find an understorey of Hazel. Typically this species will have been planted and managed on a regular basis by coppicing (see p.) to produce a constant supply of straight branches, used in hurdle-making and other woodland crafts.

A managed Pedunculate Oak woodland has near-continuous canopy cover. Only in winter and spring, before the leaves emerge, do significant light levels penetrate to the woodland floor.

In spring, a sympathetically managed woodland of this type is a floral delight to the eye, with carpets of Bluebells, Wood Anemones and Wood-sorrel intermingling with patches of Dog’s Mercury, Early-purple Orchids and Wild Daffodils. Pedunculate Oaks probably support the greatest diversity of invertebrate life of any of our trees, feeding beetles and moth larvae in abundance. If the occasional Sallow also grows among them, then there is a good chance that Purple Emperor butterflies may be present, assuming the woodland lies within this species’ restricted English range. The larvae feed on Sallow leaves but the adults – males in particular – depend on mature oak standards, using their canopies to define and defend territories. Birdlife is usually as rich as can be expected for a lowland woodland but arguably the star of the show is the Dormouse. Dependent on Hazel nuts in autumn, they occupy the oak canopy for much of spring and summer, feeding on oak flowers and insects.

A majestic male Purple Emperor surveys his domain from the canopy of a mature Pedunculate Oak.

Carpets of Bluebells are a stunning feature of managed Pedunculate Oak woodland in lowland Britain.

Although Sessile Oak often grows alongside its Pedunculate cousin, its requirements for optimum growth are subtly different and it predominates in upland and western parts of the region where rainfall is highest. Often the best remaining tracts of Sessile Oak woodland are on steep slopes, in part because the trees are less easy to fell there; in such circumstances they are often referred to as ‘hanging oak woodlands’. Try to negotiate the broken ground and slippery roots of one of these woodlands and it is not hard to see why.

Although the wildlife that Sessile Oak is capable of supporting is broadly similar to that of a Pedunculate Oak, in reality there are subtle differences. In part this may be a reflection of the generally harsher climatic conditions that it favours, although the history of land use by man sometimes plays a part too.

In lowland oak woods that have an understorey of Hazel, grazing animals were typically excluded in the past, or at the very least discouraged on account of the damage they might do to growing shoots. By contrast, many hanging woods of Sessile Oak are freely grazed by sheep and cattle with the consequence that the shrub layer is considerably reduced. Bluebells and other flowers of the woodland floor are common, but what strikes most visitors is often the abundance of ferns, mosses and liverworts. In part this is a result of an absence of competition from more palatable (in grazing animal terms) flowering plants, but the humidity of the regions where Sessile Oaks grow also plays a part. Hence the abundance of epiphytic mosses and liverworts in particular, often festooning trunks and branches well off the ground. Sessile Oak woodlands are the classic domain of nesting Pied Flycatchers and Redstarts.

Hanging Sessile Oak woodland.

Sessile Oak woodland cloaking steep hillsides on Exmoor.

In the British Isles, Pied Flycatchers reach their highest breeding densities in Sessile Oak woodlands.

Tree Lungwort.

Ash is a widespread tree in Britain, often growing alongside oaks and other deciduous species. However, in some circumstances it comes to dominate certain woodlands. It thrives if soil conditions suit it – it favours basic soils, and can tolerate occasionally waterlogged conditions, but will also grow on limestone pavements.

In lowland Britain in particular, Ash has often been deliberately encouraged and managed as a source of excellent timber. Traditionally, it was coppiced regularly to produce tall, straight poles and in some woods huge stools have developed that are hundreds of years old. Hazel coppice is often grown as an understorey beneath its larger cousin.

Ancient stools of Ash produce a succession of tall, straight poles if coppiced periodically and managed correctly.

Woodland flowers are very much a feature of traditionally managed Ash woods. Bluebell, Lesser Celandine, Dog’s Mercury and Wood Anemone are often common, with star attractions being Herb-Paris, Goldilocks Buttercup and Early-purple Orchid.

Upland limestone pavement is perhaps a surprising place to find Ash, given its tolerance of, and seeming predilection for, damp ground in other locations. Nevertheless, thrive it does, often accompanied by Bird Cherry and Rowan.

Few trees are more successful at eliminating competition from rival species than Beech, and in mature woodland it often forms such a dense canopy that competition from other tree species is essentially eliminated. Beech will tolerate a wide range of soil types, from fairly acid to calcareous. It is arguably at its finest growing on the latter, especially when covering the slopes of chalk downs. Beech woodlands in such settings have the fitting name of ‘hangers’.

Dark and gloomy during the summer months, by contrast a Beech woodland in winter is light and airy, with colour provided by the fallen leaves.

During the summer months very little light penetrates to the woodland floor. Low light levels, combined with the dense carpet of fallen leaves that covers the ground, ensures that few woodland flowers are able to survive. Those that do are restricted mainly to clearings and rides, and in such places Sanicle, Woodruff and a number of helleborines can sometimes be found. A small group of specialist plants do grow in the deep shade of Beech woodlands: species such as the Bird’s-nest Orchid and Yellow Bird’s-nest lack chlorophyll and cannot photosynthesise, relying on a saprophytic way of life for nutrition.

For many people, Beech woods are at their best in the autumn, not only because of the stunning foliage colours but also because of the intriguing range and abundance (in wet years) of fungi. Many of these are entirely restricted to Beech woodlands and some of the associated Russula and Boletus species are extremely colourful themselves.

The Devil’s Bolete is a rare and spectacular fungus that grows beneath ancient Beech trees on chalky soil.

Although it is seen only irregularly, the Ghost Orchid is the Holy Grail for British botanists. Scouring ancient Beech woods in central England represents a naturalist’s only realistic prospect of finding one in this country.

Birches are often viewed with disdain and dismissed as being little more than scrub trees. It is true that, in certain circumstances, Silver Birch, in particular, is an aggressively invasive species of heathland and newly cleared woodland on neutral to acid soils. However, in its favour is the fact that it plays host to a wide range of insects, in particular the larvae of many moth species. Most feed on birch leaves but the larva of the Large Red-belted Clearwing Synanthedon culiciformis feeds on wood, sometimes being discovered in cut stumps.

In the autumn, Silver Birches usually turn a spectacular golden yellow for a week or two. Around the same time, an amazing array of fungi put in an appearance as well, many of them only found growing in association with these trees. The best-known fungal association with Silver Birch is probably the Fly Agaric Amanita muscaria, an unmistakable and striking species. But dozens of other species are invariably associated with these trees, including several Boletus and Russula species as well as the Birch Polypore Piptoporus betulinus.

Silver Birches provide stunning autumn colours that lift the spirits.

Phil Green

The larvae of the Large Red-belted Clearwing feed beneath birch bark and the secretive, day-flying adults are sometimes spotted resting among the foliage.

The Buff-tip has an uncanny resemblance to a snapped birch twig: a convincing camouflage that increases the moth’s chances of avoiding detection by predators.

The Fly Agaric has a mycorrhizal association with the roots of birch trees (see p.), so you are unlikely to find this fungus growing anywhere else.

Downy Birch often grows alongside Silver Birch but comes to replace it in many western, northern and upland parts of the region. In terms of specifically associated wildlife, it has much in common with Silver Birch, particularly when it comes to fungi. However, in Scotland, in particular, superficially similar hardy Highland species often replace their southern counterparts. Look out for the intriguing Hoof Fungus Fomes fomentarius growing on stumps and trunks.

Nature is dynamic, and there is a general trend in all environments for newly created habitats to become colonised by increasingly more stable plant communities. In most locations this progression follows a predictable route and the process itself is referred to as habitat succession.

The impact of succession in wetland habitats is particularly striking. Marginal vegetation soon encroaches upon areas of open water, and silt builds up, gradually reducing water levels. Reeds, bulrushes, sedges and rushes then take hold and open water soon gives way to tussocky ground. The resulting mire is referred to as a fen if the water is neutral to basic or a bog if the ground is acidic. Trees soon begin to appear and those tolerant of waterlogged ground – Alder and various willow species – give rise to a woodland community called carr where once a fen prevailed. Carr is the penultimate stage in the process of succession, which leads eventually to the formation of dry land and a climax community of Oak and Ash.

Carr woodland is not the easiest of plant communities to explore and, unless the area in question is a boardwalked nature reserve, wet feet are inevitable. However, such areas are usually botanically rewarding. Insect life usually abounds too, particularly in the form of midges and mosquitoes.

The damp environment with which Alder carr is associated allows ferns and mosses to thrive in abundance.

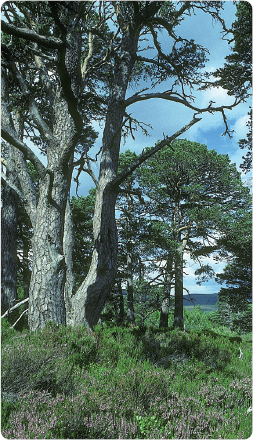

Visit the Highlands of Scotland and you will discover remnants of the ancient Scots Pine forests that once cloaked the region; these areas are often referred to as Caledonian Pine forests. In contrast to the relative paucity of wildlife found in most regimented conifer plantations, there is plenty of wildlife to find here. In Britain, Crested Tits are found only in these forests and the Scottish Crossbill occurs nowhere else in the world. Pine Martens and Red Squirrels also occur in good numbers.

Native Caledonian Pine forests are typically rather open, comprising trees of varying ages, including many dead and dying individuals of course. Typically there is a lush ground cover of Bilberry and mosses, with botanical highlights that include several wintergreen species, Twinflower and Creeping Lady’s-tresses, the latter a charming if diminutive orchid.

Native Scots Pine forests are typically light and airy, with an understorey of Juniper and Bilberry.

Twinflower is a scarce but enchanting botanical highlight of a few Scottish forests.

If you encounter conifers in Britain outside the native range of the Scots Pine in central Scotland, then (with the exception of a very few Yew woods) their occurrence will not be natural. Regimented plantations are easy enough to spot, with trees of uniform age planted a standard distance from one another. But even isolated clumps of Scots Pine found on a southern heathland are at best going to be naturalised trees, their seeds having spread from nearby plantations.

Does the fact that most conifers in Britain are introduced matter? In the case of isolated trees or small clumps, perhaps not. But, when it comes to the impact upon native habitats and wildlife, then plantations are a different matter. The dense manner in which they are planted effectively destroys the natural vegetation that once existed there – just think of the scandalous destruction of areas of Scotland’s Flow Country if you are in any doubt. But even naturalising conifers can be a threat, endangering already diminishing areas of heath-land.

The benefits of conifer plantations to a select band of birds – Crossbills in particular – is often cited in favour of tolerance, although of course not all planted conifer species produce cones that are accessible to these birds. However, anyone willing to take an overall ecological view of the process, rather than trying simply to look on the bright side of things, will realise that the losses, in wildlife terms, heavily outweigh the gains.