INTRODUCTION: BREEZE BLOWIN’ IN

Sometimes inspiration strikes like a lightning bolt, and other times it’s a slow burn. The groundwork for our little restaurant was laid decades ago, during happy summers spent with family traversing New England’s coast, including the rocky shores in Maine. Our childhood experiences scavenging crabs, clams, in-shore fish, and seaweed deeply influenced the Eventide concept and menu, as did the clam shacks and lobster pounds that are given altar-like reverence in New England. These singular, superlative experiences became so ingrained in our minds that when we set out to put modern touches on them, we had an incredible sense of nostalgia to build on.

But as we look back on the journey, we also have to be transparent about something: we didn’t know what the hell we were doing, really. By most of the laws and conventions of the restaurant industry and common business sense, Eventide should have been the entrepreneurial equivalent of a spectacular dumpster fire.

We opened in the summer of 2012 in quaint Portland, Maine—population 67,000. Although we put in some years together at Hugo’s, a trailblazing restaurant in terms of Portland fine dining, we had no hands-on experience in getting an establishment up and running. Our budget was a frayed shoestring, and we didn’t base many (any?) of our key decisions on sound restaurant business practices.

The seemingly bold decisions were actually naivety at work. We designed the restaurant ourselves on drafting paper and hired a local residential carpenter to build it out. We put in only two tables because, well, we didn’t like tables. We decided not to build a kitchen and had no hood fan. Our stovetop firepower included one induction burner and a tabletop fryer to match. We failed to foresee that our monumental stone oyster basin, dubbed “The Rock,” was going to destroy multiple floors with plumbing issues and condensation in the years to come. We opened with absolutely no art on the walls because we couldn’t afford any.

Discoveries of setbacks and our own mistakes grew more frequent, as did the daily, anxiety-driven vomiting in the shower. A peek behind the scenes at the chaos suggested that it was exactly the rookie disaster that it deserved to be.

And yet—and we say this with the same mix of shock and bemusement we’ve had all along—Eventide has been busy since day one. People even found it charming. The bighearted little city of Portland took the leap with us from the moment the doors opened. Man, do we love this town.

THE BACKSTORY

The first thing our first customer said to us, after he wandered in, not knowing we were open yet, and looked incredulously around the space, was, “Where are all the seats?” For a bunch of greenhorns who could have used some positive reinforcement at the time, that hurt. The proverbial pain was amplified because that first customer happened to be Dana Street.

Dana and his James Beard Award–winning partner, chef Sam Hayward, are the proprietors of Fore Street, which opened in 1996 as the first real, excellent, farm- and fishery-to-table restaurant in Portland. To this day, it remains the quintessential Maine restaurant (the team also owns Street and Co., Standard Baking Co., and Scales). Dana and Sam, along with James Beard Award–winners chef Rob Evans of Duckfat and Rob Tod of Allagash Brewing, were the first to bring any kind of national food and beverage media attention to Maine.

In fact, it was at Hugo’s, Rob Evans and his wife Nancy Pugh’s restaurant, that the three of us (Arlin, Andrew, and Mike) met. Arlin arrived first as general manager in 2009, after graduating from the Culinary Institute of America in Hyde Park, New York, and working a mix of front-of-house positions in restaurants in the Hudson Valley. Andrew came through a short time later as sous chef, after stints at Thierry Rautureau’s Rover’s in Seattle and Ken Oringer’s Clio in Boston. The last piece of the puzzle was Mike, who started in 2010 as a line cook, after working restaurants, getting a graduate degree, and skiing sick lines in Colorado.

At the time, Hugo’s was considered a pioneering restaurant, bringing modern elements into the tradition-bound fare of New England and, more specifically, the cuisine of Maine. And it punched above its weight, because Rob had come to Portland in 2000 from chef Thomas Keller’s The French Laundry in the Napa Valley, one of the world’s best restaurants and an incredible wellspring of culinary talent. Hugo’s was a modern restaurant that followed high gastronomic trends from Napa, New York, and western European capitals. Despite the accolades that it garnered, it had never really been embraced with open arms by the community the way Eventide was later (things have changed now, but that’s for another book). We learned that Mainers like things that are simple and low-key, rather than superconceptual.

Nevertheless, the heritage, heretical element, and ethos overall at Hugo’s spoke to us at a deep level, and given that Rob and Nancy had largely stepped away from the day-to-day at the restaurant by the time Mike arrived, the three of us had the chance to develop our own collective point of view. That’s pretty rare, to be thrust into that kind of creative opportunity together, and we intended to push in our own direction.

Fast-forward two years, and some pretty powerful forces (hubris, opportunity, and pregnancy among them) coalesced to vault us into the terrifying world of restaurant owner-operators. And while we were in way over our heads in so many ways, we were lucky to have a few things going for us: a wave of change in the restaurant world and in Portland, an incredibly supportive local community, and the best ingredients on earth at our fingertips, to name a few.

A RABELAISIAN DETOUR

Don Lindgren and his wife, Samantha Hoyt Lindgren, owners of one of the two or three greatest culinary bookstores in the world, Rabelais: Fine Books on Food & Drink, are the spirit guides and keepers of the culinary flame in Maine. We are in their debt in more ways than one. The original Rabelais location next to Hugo’s was a place where chefs, cooks, barkeeps, and all manner of others would go to escape the grind for just a minute. We’d duck over there during prep for Hugo’s service, aprons and all, just to double-check this or that from the 1999 El Bulli cookbook. We basically had this world-renowned culinary research institution, run by two scholars of gastronomy, at our disposal. We learned more there than we could have in just about any other way (none of us had the time or resources to travel widely and immerse ourselves in global cuisine).

Don’s memories of that moment in time ahead of Eventide’s opening set the scene. “The question we got asked the most was, ‘Where should I go to get a good drink and eat some oysters and clams?’ and I didn’t have much of an answer,” he often says with an incredulous laugh. The three of us were in the same predicament, and we grew more and more focused on the idea that there was a gap in Portland that needed filling.

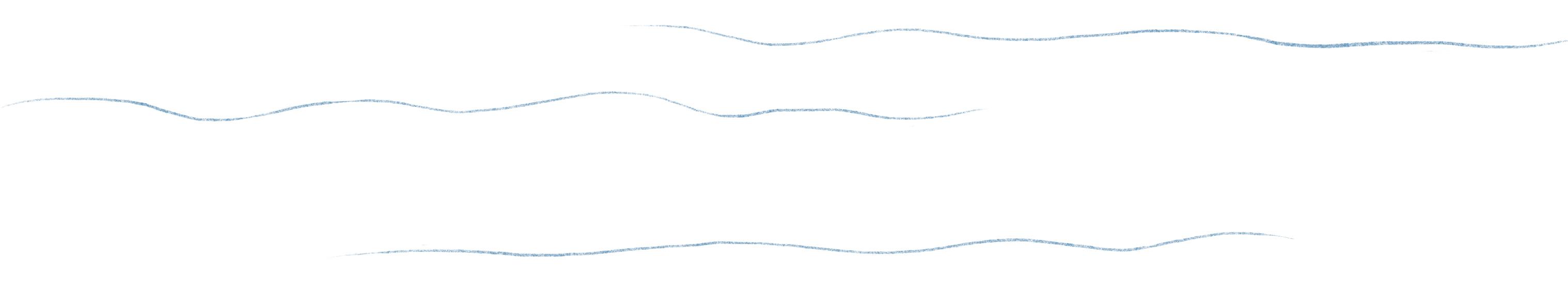

THE IMPORTANCE OF SEAFOOD SHACKS

It’s hard to overstate how important the shack experience—sitting down to slurp shellfish and eat fried seafood with loved ones and friends—is in this part of the world. Like soul food joints in the South, barbecue houses down the Mississippi and in Texas, and roadside diners in the Midwest, these informal seafood houses are the hallowed ground of our food culture in New England. Fancy restaurants come and go, leaving their mark and helping push American food forward, but good seafood shacks, serving tried-and-true New England staples, endure.

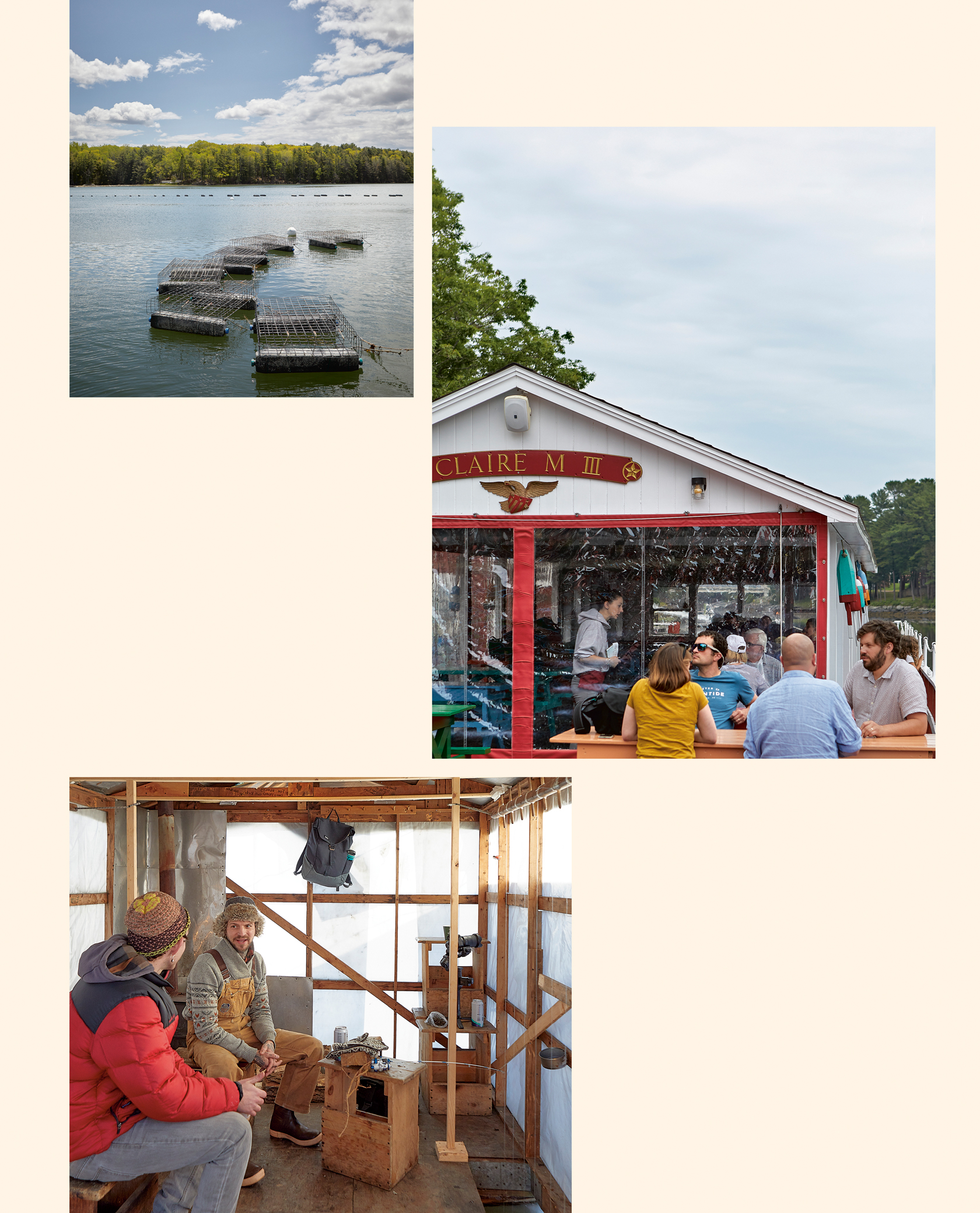

It’d be tempting to call places like J. T. Farnhams in Essex, Massachusetts, and Beal’s in Southwest Harbor, Maine, relics that survive because they’ve been around forever and they have a view, but that’s missing the point. They are as relevant as ever because they serve unpretentious food that people nearly universally love. Moreover, there is nothing that feels more honest than a place that simply prepares the bounty that is close at hand.

And because the best of these restaurants seem to spring out of the fisheries of the area, it’s fascinating to see how they change as one moves up and down the New England coast. New York and Connecticut are famous for their oyster bars; the smell of fried scallops and clam chowder drifts from every seafood house in southern Massachusetts and Cape Cod. Northern Massachusetts, the land of the soft-shell clam, is famous for its fried clam shacks. Moving north to southern and Midcoast Maine, you’ll begin to see more and more lobster rolls. Once you reach “Down East,” the term used for the northern third of Maine’s coast, it’s full-on lobster pound territory, where you’ll find the best lobsters in the world, live or steamed, in abundance.

Our Top Seafood Shacks in Northern New England (North to South)

Whenever we can, we like to shout out the amazing families and proprietors that keep these gems alive and kicking.

Abel’s Lobster Pound

Abel’s Lobster Pound

13 Abels Lane, Mt Desert, ME 04660

Year opened: 1939

Owners: The Squires Family

Go for the steamed lobsters, lobster rolls, lobster bisque, steamed clams, and clam chowder

Beal’s Lobster Pier

Beal’s Lobster Pier

182 Clark Point Road, Southwest Harbor, ME 04679

Year opened: 1969 (wholesale operation opened in 1932)

Co-owner: Stuart Snyder

Go for the steamed lobsters and clams

Young’s Lobster Pound

Young’s Lobster Pound

2 Fairview Street, Belfast, ME 04915

Year opened: 1930s

Owners: Fourth-generation family owned

Go for the steamed lobsters and clams

McLoons Lobster Shack

McLoons Lobster Shack

315 Island Rd, South Thomaston, ME 04858

Year opened: 2012

Owners: The Douty Family

Go for the lobster roll and clam dip

Five Islands Lobster Co.

Five Islands Lobster Co.

1447 5 Islands Road, Georgetown, ME 04548

Year opened: 2007

Owners: Keith and Gina Longbottom

Go for the steamed lobsters, lobster rolls, steamed clams, fried shrimp, and fish chowder

Holbrooks Wharf

Holbrooks Wharf

984 Cundy’s Harbor Road, Harpswell, ME 04079

Year opened: 2005

Owner: The Holbrook Community Foundation

Go for the fried seafood of all kinds, steamed lobsters, and steamed clams

Day’s Crabmeat & Lobster

Day’s Crabmeat & Lobster

1269 US-1, Yarmouth, ME 04096

Year opened: 1920

Owners: Randall Curit and Jennifer Rief

Go for fried seafood of all kinds, and the lobster and crab rolls

The Clam Shack

The Clam Shack

2 Western Ave, Kennebunk, ME 04043

Year opened: 1968

Owner: Steve Kingston

Go for fried seafood especially fried whole belly clams; boiled lobster; lobster rolls; and clam chowder

Bob’s Clam Hut

Bob’s Clam Hut

315 US-1, Kittery, ME 03904

Year opened: 1956

Owner: Michael Landgarten

Go for clam chowder, lobster stew, fried whole belly clams, and the Lillian fried clams

Chauncey Creek Lobster Pier

Chauncey Creek Lobster Pier

16 Chauncey Creek Road, Kittery Point, ME 03905

Year opened: 1948

Owner: Ron Spinney

Go for raw oysters and clams, chowders, lobster and crab rolls, and steamed clams

J. T. Farnhams

J. T. Farnhams

88 Eastern Avenue, Essex, MA 01929

Year opened: 1941

Owners: Terry and Joseph Cellucci

Go for fried whole-belly clams, seafood chowder, lobster and crab rolls, crab cakes, and lobster bisque

Woodman’s of Essex

Woodman’s of Essex

119 Main Street, Essex, MA 01929

Year opened: 1914

Owners: The Woodman family

Go for fried seafood of all kinds, especially fried whole-belly clams; boiled lobsters; and clam chowder

MAINE’S MIDCOAST: CENTER OF THE UNIVERSE

We recognize how lucky we are, trust us. Not only do we have a rich regional tradition of simple, honest food, but we also have the natural bounty of Maine. Lobster may be what the state is best known for, but overall, there’s no place on earth with better fish and shellfish. Portland sits on the southern edge of Casco Bay, a fertile kingdom for fish like mackerel, cod, haddock, striped bass, bluefish, and Western North Atlantic bluefin tuna. The innumerable marshes and finger estuaries that marry the Casco Bay and the surrounding Gulf of Maine to the coastal mainland are perhaps the most brilliant oyster beds in the world.

Although Dana Street, Sam Hayward, Rob Evans, and Rob Tod were the first to bring national food media attention to Portland, the general public and even some bold-faced food names have been hip to Maine for a while. Of course, the oyster bars and seafood shacks of New England have drawn people for decades, but it’s still kind of an open secret that some of the most legendary chefs in America of the last fifty years have built their reputations in part on, and in partnership with, Maine’s watermen and waterwomen.

Giants like Thomas Keller of The French Laundry, Eric Ripert of Le Bernardin, Jean-Georges Vongerichten of Jean-Georges, and the late Jean-Louis Palladin of Jean-Louis at the Watergate all built deep relationships with local entrepreneurs, such as Rod Mitchell of Browne Trading Company, the late Ingrid Bengis-Palei of Ingrid Bengis Seafood, and George Parr of Upstream Trucking. This is the pipeline that helped introduce America to a wider variety of high-end seafood in the 1980s and 1990s, including such delicacies as razor clams and sea urchins, and lesser-known types of fish, oysters, and other shellfish. Concurrently, Japanese processors were quietly setting up buying stations along the coast of Maine for bluefin tuna, sea urchin, glass eels, and surf clams to buy cheaply and ship directly to the Tsukiji fish market in Tokyo.

In addition to the bounty from our waters, we’re also lucky to have access to great vegetable and livestock farms up and down the state, many of which are banded together in the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association (MOFGA), the oldest and largest such state network and certifying body in the country. Our close partners at Stonecipher Farm in Bowdoinham, North Star Sheep Farm in Windham, Southpaw Farm in Freedom, and Green Spark Farm in Cape Elizabeth all navigate a short season to raise, grow, and preserve products like pork, lamb, and an amazing panoply of vegetables. It is really hard to mess up products this good if you care even a little bit.

What truly sets the whole ecosystem apart is how incomparably cold, clean, and resilient it is. There’s still a lot of work to do to protect local waters and lands, and we will continue to play our part contributing to the effort. It’s an existential issue for us (and humanity, of course), because any success we’ve had has a lot to do with Maine’s ecosystem and status as a vacation and tourism destination.

The buildup to Eventide was decades in the making, thanks to our childhood experiences with seafood shacks. When we did decide to take the leap and open, we caught lighting in a bottle. As we noted, we opened Eventide in part because you couldn’t experience the amazing variety of Maine oysters in Portland restaurants as recently as 2012.

That seemed crazy, but it also represented a huge opportunity. Portland was the perfect place to seize it. Don Lindgren explained why it made some economic sense to give Eventide a go:

Portland has a couple of things going for it. First, the city’s commercial storefronts and spaces are predominantly small and inexpensive, relative to big cities. That sets up the ability for chefs to own their own restaurants, even without partners or venture capital backing, which in turn means that Portland eateries are more likely to exhibit the vision of the chef, rather than investors. It leads to more chance taking and more creativity.

In the aftermath of the Great Recession of 2008, Portland took off from the starting line to become what Lindgren described as one of the best food cities in America. Almost by necessity, there’s a thriving restaurant culture here. Without the kind of widely diversified economy that bigger cities have, a larger relative percentage of Portlanders work in full-service restaurants than in any other city in the Northeast. A pipeline of great talent from other cities finds its way here because rents are relatively cheap (for now), the restaurants are great, and the quality of life is outstanding. And the national food media, in its infinite wisdom, has chosen Portland as one of its poster children for what a great small city dining and drinking scene looks like.

ONE GOOD REASON TO TRY

This was the ideal backdrop against which we stumbled forward into Eventide. Rewind to 2012: Rob and Nancy had made no secret of their interest in selling Hugo’s to focus on their more casual and higher-volume restaurant, Duckfat, down the street. Nancy even had Mike, an English major, help write the real estate listing. Around the same time, Don and Sam Lindgren announced their plans to move the Rabelais bookstore out of Portland and relocate it about twenty miles south to Biddeford.

The idea of buying Hugo’s had been something of a running joke among the three of us, because we were the ones using literal and proverbial zip ties to hold the restaurant together. If buying one seemed like a bad idea, then throwing a second restaurant into the mix should’ve seemed preposterous.

But there we were, with unfounded confidence and an opportunity to be owner-operators of two restaurants for basically the price of one. With very little planning or lead time, we cobbled together barely enough money from family and friends to purchase Hugo’s and the Rabelais space, which would later become Eventide (we shared one kitchen for both restaurants at the beginning, and still do, to some extent). What we lacked in business sense, experience, and resources we resolved to make up for with really hard work, deep respect for the food we were serving, and the desire to make people really happy.

After signing the final Hugo’s purchase papers with our mentors over a pint at an Irish pub, we were new owners of a turnkey, high-end, low-volume restaurant and a tiny raw space. As a result of our inexperience, we laid out endless little stumbling blocks in our own way, but we had to get moving quickly, because every minute lost was a dollar lost that we couldn’t afford to burn. Instead of trying to tiptoe our way through the thicket, we just decided to barrel ahead. We wanted to do the unexpected, often and unselfconsciously, with our food and the level of generosity we showed our customers.

PUSHING OUT THE WALLS

Over more wings and beer than we care to admit, we dragged our fantasy of a modern New England oyster bar and seafood shack into reality.

Arlin, the one among us with solid front-of-house experience, got things started by drawing space plans for Eventide on draft paper. As we looked at the weird, stubby little L-shaped footprint over and over and over again, all we knew was that we wanted to create a space where people were going to have fun and let their guard down. We planned as big a traditional bar as was feasible and lined the huge glass windows with countertop seating facing the street. Why? Because bars are more fun, in the minds of three young dudes.

With most of the space allocated to barstool seating, we had enough room remaining for just two picnic tables, like the ones you might find out back of a seafood shack. Andrew’s brother-in-law built them. The grand total seating number was thirty-two.

The raw bar, which we explain in detail in chapter 1, was where we really wanted to break boundaries—both in New England and beyond. Variety was priority one. It felt critical to showcase a wide range of Maine oysters, which was still pretty much unheard of, even in Portland. We wanted the bar to be full of at least a dozen types every day, piled high and shucked to order in front of the guest. It was all about keeping things honest.

Beyond the oysters themselves, we also wanted to provide creative accoutrements like shaved ices made from kimchi, horseradish, and hot sauce. That felt almost radical when you consider what traditional oyster bars and seafood shacks usually serve. Even all these years later, we challenge you to think of the last time you ordered a dozen raw oysters and were even given the option of embellishments beyond cocktail sauce, mignonette, lemon slices, and maybe hot sauce (not that there’s anything wrong with any of that). We just saw so many opportunities to elevate rich, salty oysters with bright, spicy, creative touches.

We also dreamed of building out the raw bar concept with our idea of “New England Sushi”—giving raw shellfish and fish a bunch of new preparations as crudos. We weren’t going to balance tiny tranches of fish atop vinegared rice, but we definitely wanted to take cues from great sushi chefs. We know that doesn’t sound novel, but at the time, crudos were not on every high-end restaurant menu, regardless of cuisine, as they are today.

FINISHING SPEED

Then came the sacred sea cows: classic seafood shack fare and traditional Maine cuisine. The former, as we mentioned, is a singular dining experience that draws loyalty from generations of families and waves of attention from summer weekenders and global food adventurers. The latter is less well known, or perhaps less well defined, because it’s not that different from any other homespun regional cuisine. Maine is all about simple, hearty, honest food with lots of soups, stews, potatoes, local seafood, and preserves, but not a lot of frills. Make that no frills. But we were trained in the cuisine of ambitious, high-end restaurants that forever ask, “Can’t there be more frills, tweaks, or embellishments?”

We found our footing between those competing forces with Eventide’s Brown Butter Lobster Roll (this page), the foundation of any success we’ve achieved. After playing around a lot with classic setups of hot buttered lobster chunks and cold, creamy lobster salad on a variety of buns, we eventually figured out that we didn’t want to go the classic, split-top, griddled hot dog bun route. We didn’t have a griddle, for one, but more importantly, we knew that we wanted to do something different and (respectfully) plant our own flag in the sand.

Being part of the generation of chefs who swam in Chef David Chang of Momofuku’s wake means we’re not satisfied with conventional wisdom, and we’re big fans of steamed bao buns. The bao is a perfect, tender little pillow to wrap around your delicious filling of choice. It is a little miracle of Chinese gastronomy, because it unfailingly elevates (and never detracts from) whatever you cram in there.

We already had a steamed bun recipe wired for a bar snack at Hugo’s, and we just rolled it differently to create the split-top look. With the lobster, we found our way pretty quickly to brown butter, which has a jammier and richer flavor than uncooked butter; it provides the roll with caramelized flavor that was lost without the griddled bun. Creating the lobster roll was the most calculated culinary project we took on ahead of opening the restaurant. Everything else was wild improvisation and survival-based cooking.

People came in droves more or less from the beginning. A week or so after his initial visit, Dana Street came back with his entire management staff, and we put them in front of “The Rock” to drink in the general liveliness and all the interaction between customers. People were coming in and having drinks and eating a whole meal standing at a stone ledge. Everyone in the restaurant seemed like as if they were at a shindig together. As it turns out, thirty-two seats were enough to party.

TAKE A LEAP

Now that you’ve heard the backstory, here’s our pitch on the food and recipes that follow in this book. We hope you will come back to this book every summer, just as tourists and locals flock to the classic New England oyster bars and seafood shacks that are the inspiration for Eventide Oyster Co. It’s a book made to pack for a week at the beach or to stumble upon while perusing the bookshelf at the summer rental. For any time of year and wherever you may be, it offers the best insight we have, acquired in almost a decade of hard labor and lessons, about buying and preparing fresh, seasonal seafood and other coastal favorites.

We want you, dear reader, to feel comfortable putting together a raw seafood spread for appetizers at your next brunch get-together; a brown butter lobster roll (this page) with a green salad and a glass of pale wine, solo on a Tuesday night; some lobster stew (this page) for a meal on the deck or the balcony; or a halibut tail bo ssam (this page), our version of the ultimate Korean BBQ party spread, at your next dinner gathering. You can make them all possible with help from this book. Our only request is that you share with others what we’re sharing with you, whenever you can. It’s about spreading the familial magic that comes with picking up your loaded trays at the oyster bar or seafood shack counter, after a wait across seasons and long lines, and getting them to the table for friends and loved ones.

Go ahead and confidently serve fish in your home! Take a leap! Do something unexpected and fun, because it’s worth it. When we opened Eventide, we didn’t really know what we were doing either, but we just took the leap and trusted that fresh, high-quality seafood would do most of the work on its own. Done right and responsibly, it’s about the cleanest and most beautiful eating there is.

Final note: These recipes were developed and refined by all of us, with help from a huge supporting cast, including our opening bar manager (and wartime consigliere) John Myers, and our pastry chef Kim Rodgers. Sometimes we have a personal story to share about the recipe or a really important tip for making the dish, which is why you’ll see our names after some headnotes. No names means the recipe comes from all of Team Eventide.