It must have been about this time that I became aware that I had a godfather, and that he was a godfather both to admire and to like. His name was Colonel Richard Elkington, and I am named after him. He was a close friend of my father and lived out at Adbury Holt, a mile or two south of Newbury. A story remained popular in our family of how, one day at the Newbury races, my father was wearing a pair of brightly coloured socks, with which he was rather pleased, when Colonel Elkington came up to him and said ‘Hallo, Flash Alf!’ After this coloured socks, in our family, were always referred to as ‘Alfreds’.

However, there was a whole lot more to Colonel Elkington than coming up with snappy cracks at the races. His tale is a strange one. I am not sure that I recall it with complete accuracy, but I will tell what I believe I was told. At the outbreak of the First World War, Colonel Elkington - a regular officer, of course - was commanding an infantry battalion. The battalion formed part of the British Expeditionary Force - the Old Contemptibles - and took part in the battle of Mons and the subsequent retreat.

One evening during the retreat, Colonel Elkington had carried out orders in placing his battalion in and around a French village, prepared to defend it. There was still a fair amount of light left when a German officer came to battalion headquarters under a flag of truce. (At the beginning of the war, there was less sheer hostility between participants than later: everyone has heard of the fraternization of Christmas, 1914.) The German officer suggested to Colonel Elkington that he might quite practicably re-position his battalion half a mile back, out of the village. It would, he thought, make no difference whatever to the battalion’s strategic advantage (or to anyone else’s near them), but it would make a lot of difference to the village full of civilians, because as things stood the Germans were going to have to shell it.

Colonel Elkington, a humane man, thought it over and decided that the German officer was about right. As he sat thinking, no doubt he could see the girls and the children in the streets, making friends with his soldiers, as they always do. I don’t know how long he had to make up his mind, but anyway he took the battalion back to a fresh position behind the village.

The result of this, at the conclusion of the 1914 campaign, was a court-martial. I don’t know what the sentence was, but as the story was told to me, Colonel Elkington left the army. It may very well have been his own decision. He joined the Foreign Legion and served in it throughout the rest of the war. However, he was not without friends who knew his worth, and when the war was at last over there was pressure to get the case re-opened. Finally, the whole thing was reviewed and the Colonel was reinstated without a stain on his character.

The Elkingtons were a well-known local family and I have always felt proud of my godfather, who never failed, by the way, to come down handsome at Christmas and on my birthday. His nephew, Sir Richard des Voeux, commanded 156 Parachute Battalion at Arnhem, where he was killed.

Being a doctor’s son, I naturally had a certain amount to do with the hospital, which was a mile away from our home, at the foot of Wash Hill. My father, of course, was always in and out, and not infrequently I might be with him. The hospital was a thriving one. Entirely privately supported, it was the pride of Newbury. Every ball, every fete, every Boy Scouts’ melarky was in aid of the hospital. The doctors, the matron and the sisters were local personalities. It was an integral part of Adams family life.

My first memory of the hospital goes back to when I was very small - I think, three. I had a nasty earache and my father (ever mindful of Robert, no doubt) decided to take me down to the hospital, where I was put to bed. All the time, I seemed to be hearing a continual, disturbing whispering and susurration, as of leaves, which gave me no peace. Someone came up to me and asked ‘Can you tell me in what way it hurts, dear - how you feel?’ I replied ‘There’s a garden in my ear.’ I had not experienced the last of that ear, as will be told.

The two senior sisters at the hospital were powers in their own right. Their names were Sister Tomlinson and Sister Dickinson - Sister Tommy and Sister Dickie. They were generally credited with a lot of medical wisdom, and the doctors used to remark humorously that they wouldn’t dream of prescribing or doing anything for a patient without either Sister’s approval. They were kindly dragons - my goodness, how they worked, too! - and to me, as I grew to know them, they seemed more and more like aunts. (‘Hullo, young Richard; out of my way, now!’)

But the nicest person in the hospital, and one of the fondest memories of my life - like Miss Langdon - was Matron Miss Adamson. She was, perhaps, rather an unexpected person to be a matron. She was then in her forties, I would now guess, with fine features and swept-back, white hair. She was quietly spoken and very gentle. Indeed, I never heard her raise her voice. To me she was, quite simply, a second mother. She was someone to whom I could tell everything (such as the Ruth Hubbard problem), and find her invariably understanding and kind. To me, of course, she, as Matron, assured, cool, slim and nice-looking in her dark blue uniform and flowing white head-dress, was a figure to be looked up to and trusted implicitly. The respect with which everyone treated her was plain to be seen. But they weren’t free to come into her private room, as I was. She evidently liked me, and this meant a great deal, because a lot of grown-up people decidedly did not. I was spoilt, wayward and inconsiderate: but I was much less so with Matron, because there was something about her which made you behave as you should. The general atmosphere - even the characteristic smell - of the hospital, too, inclined a small boy towards a certain restraint. I knew well enough that this was a place where people came because they were ill - many gravely ill - and that my father’s livelihood and working life were centred on it. It was a place to which to come and talk seriously to Matron: it wasn’t a place to kick up your heels.

The hospital possessed great numbers of toys and games, and Matron used to let me play with these, and sometimes let me borrow them. I recall in particular a toy theatre, the like of which I had never seen. The cast were two-dimensional, on stout cardboard and properly jointed. At their backs were horizontal strips of sticking-plaster. In these you inserted one arm of a stiff, T-shaped wire, the long arm of which extended out through a horizontal slit which ran the length of the stage half-way up the back-drop. With this they were manipulated from back-stage. I can’t remember any toy ever giving me more pleasure.

Sometimes Matron would take me with her when she went round the children’s ward. I would follow discreetly behind her as she went from bed to bed, speaking to each child in her low, gentle voice. My goodness, weren’t those children just about glad to be ill in hospital? This was luxury. A lot of them had never known anything like it in their lives. They were poor, most of them, from homes in the courts and alleys of Newbury sixty years ago. They were in no hurry to get better - especially at Christmas-time. Shy and inarticulate, they mostly answered Matron in monosyllables, calling her ‘Miss’. I remember her stopping by one bed and asking a little boy of about my own age to try to see whether he could keep his hands still. He couldn’t, but she told him he was much better and going on well.

‘What’s the matter with him?’ I asked Matron, when we were well past the bed.

‘It’s St Vitus’s dance, dear,’ she said. ‘People who have that can’t keep themselves still’

‘Will he get better?’

‘Oh yes. He’s better than he was to begin with.’ There was a singular quality about Matron of which I was intuitively aware, though I never thought about it much. It was simply a part of her self, as I came to know her; a kind of distance, of melancholy - the pensive gravity of a saint, one might almost think. It was as though there were some preoccupation - something untold which she never quite dismissed from mind. I believe I was possibly more sensitive to this than many grown-up people (I have never talked to anyone about it), simply because they generally spoke to her on some urgent matter or question of their own, while I, alight with affection, was nearly always waiting for what she would say to me. Would she have liked to have children of her own? Did the sort of things she often had to deal with upset her, I wonder? I can’t tell - I never saw her after childhood. I’m glad I knew her: I’ve never known anyone who seemed at all like her; a lady out of Walter de la Mare, always more or less inwardly aware of some world beyond.

Many years later, I learned that Matron had died in a mental hospital.

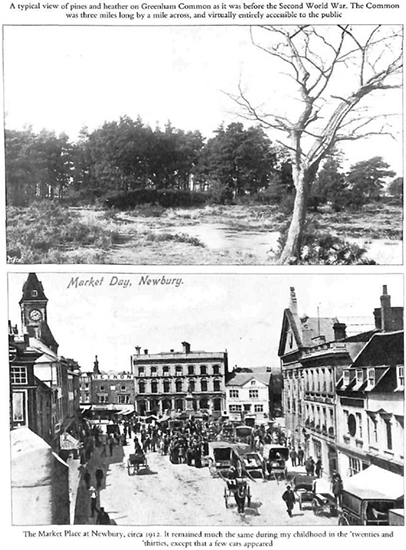

It was during these last years of childhood - before I went to boarding school - that I became a film fan. These were the days of silent pictures - a new and important part of life in the nineteen-twenties to millions of people who had never known anything at all like the cinema before. Of course, those films are watched now with hindsight, in the light of the social tidal wave of the talkies of the ‘thirties, the big luxury cinemas - the dream palaces - the great stars like Clark Gable and Greta Garbo. It must be remembered that people in the ‘twenties had no idea that all this was coming, and found silent films wonderful enough. I can remember an old market woman, sitting next to me, utterly engrossed in The Adventures of the Flag Lieutenant. I can’t recall who played the Flag Lieutenant, dashing and handsome - his name in the story was Dicky Lascelles - but they were all in China, and the English heroine was isolated, alone in her house and threatened by an uprising of evil Chinese. However, the Flag Lieutenant, of course, was on his way. As the film kept cutting from an Evil Face at the window to the heroine holding a phial of poison between her slim fingers and wondering whether the time had come to swallow it or not, my kindly old neighbour kept repeating ‘Oh, Dicky, come quick!’ and became quite ecstatic when, of course, he did. Not that I was any the less absorbed. I hadn’t grasped, myself, that it was poison; and of course I knew nothing of the Fate Worse than Death, but when you’re seven or eight you can easily become enthralled by things that are enthralling surrounding grown-ups; and anyway I knew at least that the Flag Lieutenant was coming to rescue her.

There was little glamour - in fact there was none - about those old silent cinemas. They were a great deal smaller than the new, purpose-built talking picture cinemas of the ‘thirties. In many cases they were converted Territorial drill-halls, built in the Edwardian days of Kiplingesque patriotic fervour. The Everyman at Hampstead remains a perfect example. The seats weren’t unduly comfortable and sometimes, in those smaller auditoria, you were conscious of a good deal of pipe and cigarette smoke in the air; but you were close enough to the relatively small screen. I remember that in the Picture Palace at Newbury there was an old-fashioned clock on the wall which was kept lighted by an electric bulb. It said ‘Scruton’s for Value’ round the edge, and you had this in the tail of your eye all the time.

Then there was the three-piece ensemble, piano, violin and ‘cello. Their job was to sit in an enclave below the screen and play music appropriate to the various scenes of the films, which had, of course, no other accompanying sound. They were very adroit, too. As I didn’t listen consciously to what they played - I just took it as part of the story, as I was meant to - I can’t say whether they had a large repertoire; but in after years I found that I was already familiar with things like the finale of the William Tell overture, the triumphal march in Aida and the ballet music from Rosamunde. They seemed to have it all worked out. I suppose they must have had a private show to themselves before each three-day run. It can’t have been too exacting a job, for in those days there were no continuous performances. There were two a day, I think; afternoon and evening.

The stories, in films which contained no dialogue except for occasional captions or titles, necessarily remained simple and straightforward. The endings were nearly always happy. This suited the mentality of most of the audience, who were unsophisticated compared with audiences of today. They were also - most of them - much more simply and uncompromisingly moral, and would have felt their self-respect damaged by watching anything involving adultery or promiscuity (but not the infliction of pain). A fair number of people did not go to the cinema at all, considering it immoral and a bad influence. One of these was Thorn, who would go only to Charlie Chaplin. This shows his excellent taste, for Charlie Chaplin surely remains among the most enduring figues from the days of silent films.

All manner of ingenious devices were used for the stories of films so that they could get by with a minimum of dialogue. There was a lot of miming, so that the acting now seems grotesque and laughable. The heroine would hold up her hands, open her mouth and shake her head in anguish: the hero would go down on one knee to her and clasp his hands: the villain went in for snarls, sidelong glances, sneers and so on. These contortions were conventions, accepted by the audiences of the day. The titles, when they came, were brief and simple. The one everybody remembers is ‘Came the dawn.’ Others might be ‘As fast as possible!’ ‘Where is she?’ ‘The train is coming!’ etc. I particularly remember the punch-line in a boxing film called The Ring, when at the end, the hero’s brother, after the lost fight, said to him ‘I knew you’d lose, so I betted on the other chap!’ Exeunt ambo, with the winnings, to a quiet and happy life.

Douglas Fairbanks needed few titles. He leapt from balconies, fought five men at once, sword in hand, and so on. More than him, however, I enjoyed Harold Lloyd. Harold Lloyd was a typical, modern, nice young American, with a big smile, horn-rimmed glasses and check plus-fours. His was always the old, old story of the despised, silly fool who makes mistakes, but overcomes all hazards and wins the day. His own particular way of dispensing with dialogue was Danger. He would be the absorbed, monomaniac butterfly collector, net in hand, hunting a rare species out along a plank a hundred feet up, or along a girder which a crane proceeded to lift high into the air. I understand that he really did these vertiginous stunts himself, for in those days there were no specialist, professional stunt men and no trick photography. I like the memory of this probity: the audience believed that he hung upside-down by his ankles from a suspension bridge, or drove a car into a lake - and he actually did.

Bebe Daniels was a star of the silent days, too, before the introduction of talking pictures. I vividly remember one of her ‘no need for captions’ lines. It was swimming. The film was called Swim, Girl, Swim! At the climax, she arrived late for the crucial swimming race in a car. She dived from the roof of the car and off a bridge into the already-started race and, of course, won it.

But best of all, from my point of view, was Rin-Tin-Tin. Rin-Tin-Tin was an Alsatian, the wonder dog. His ploys were irresistibly gripping to an eight-year-old. He escaped from the villains’ hideout, where his master was held prisoner, and then led the police back to it; he guided the wounded, staggering hero across the mist-enveloped moor; rescued the heroine from burning houses or flooding mills; guarded lost children and so on. I could have watched him for ever and never minded that he usually did much the same things in every film.

In those days, apart from the thin accompanying music up front, below the screen, the auditorium was a great deal more still and silent than in today’s cinemas - except for laughter, of course. As performances were not continuous, there was little coming and going during the show; there were no ice-cream girls or the like. I believe there were a few local advertisements, but they were slides. It was darker than today, and I remember watching the flickering, bright beam, a cone expanding from the projection-box to the screen, and marvelling at the miracle of moving pictures. It was not uncommon to hear someone reading the captions aloud, sotto voce, for the benefit of a companion who couldn’t read.

Certification was lax, as far as I recall, and in practice anybody could go to anything. Parents exercised their own discretion. But I couldn’t go alone, simply because the Picture Palace was right up at the other end of the town and it was too far. With the main film there was always an instalment of a serial which ended at a cliff-hanging point, to make you come again next week. Very often, of course, I couldn’t come again next week, and hated missing the next instalment. Later on, in the ‘thirties, when Boris Karloff started his fearful larks, it went for granted that I wasn’t allowed to go. I’ve never seen Frankenstein.

I long to recall as much as I can from those days before I was nine and went to boarding-school, for in many ways they were the happiest of my life, an age of innocence so complete - that is, knowing no invasion or disillusion - that later on, in about 1949, I reacted with instant recognition to Dylan Thomas’s poem ‘Fern Hill’ . I suppose it was easy at Miss Luker’s - too easy, really - and there was little to contend with, there or at home. It seems that way in memory, but perhaps only because of the boarding-school contrast which followed.

I remember the old man, Faithfull by name, who used to come every summer, in late June, to scythe the long grass in the paddock. I loved the long grass - I still do - and it always seemed to me that with its scything the summer moved on to its second phase; hot and dry, with yellowing corn, midges and wasps and the cuckoo gone or soon to go. You couldn’t chat to Faithfull as you could to Thorn; he’d just say ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ as he went on swinging his scythe, stopping every now and then to stand it up and whet it. The tall midsummer growth fell in rows; brome and melick, foxtail and cock’s foot, sorrel and buttercup and moon daisies. When it was all done, I used to be allowed to have a hay party for my friends: we played with the hay in every way we could think of; hay houses, steeplechase courses, and who could build the highest pile. A day or two later it was all raked up and carted away: only the short grass left, and horseflies in it to bite your ankles through your socks.

You seldom or never hear a corncrake now; or a nightjar. But in those days they were nothing much to remark. I never actually saw either, but often heard corncrakes in the big cornfield on the other side of Monkey Lane. The nightjar I used to hear from my bed - a curious, sustained bubbling sound, almost like purring. He seemed to like the pine trees on the western edge of the garden, and was often to be heard there on summer nights.

I remember discovering that I’d at last got enough strength to be able to play the pianola alone, unaided. It takes a certain amount of muscle-power to push down the pedals - and to keep pushing them down steadily until the end of the roll. We had a whole ottoman full of rolls: I suppose my father must have bought them, along with the pianola, quite soon after his marriage to my mother in 1910. There were all sorts of rolls, which I played indiscriminately and enjoyed equally: a selection from The Beggar’s Opera; from Rose Marie; from Dancing Time; ‘If you were the only girl in the world’; ‘Over There’ (the American march); and, above all, Chopin and more Chopin. I came to know the waltzes well, without having any notion of their fame or supreme quality: I just knew I liked them. I used to play until my legs got so tired that I couldn’t go on any more. Then I’d climb out of the drawing-room window - easier than going through the hall and out of the door - and perhaps, if it was high summer, pick a bunch of white jasmine for my mother from the bush growing up the end post of the verandah.

I remember the annual Two Minutes’ Silence on 11 November. I dare say that anyone who hasn’t experienced it as it was kept in those days will find it impossible to imagine. Whatever day of the week 11 November happened to be, the Silence was observed on that day. In London and the other main cities of the country, guns were fired on the stroke of eleven o’clock. Elsewhere, the wireless sufficed, or signals were given by the police, or by soldiers firing blank. Thereupon everything and everybody, wherever they were and whatever they were doing, stopped exactly as they were for two minutes, until the guns fired again. It was more than impressive: it was overwhelming. I suppose there can never have been anything like it: streets, cities full of people standing perfectly still and silent. Anyone who was driving a car, taxi or ‘bus stopped the engine, got out and stood in the road with bowed head and hat in hand. In the shops, the assistant who was tying a parcel laid it on the counter and the lady who was paying for it put down her purse and stood opposite. Often, one saw tears on the faces of grown-up people.

I recall, one 12 November, seeing a photograph on the back of the Daily Mail of a taxi-driver in London having his name and address taken for not stopping his engine. It’s occurred to me since to wonder at what point the policeman intervened and how the photograph came to be taken.

This universal observance (and enforcement) was based entirely on public feeling (and guilt for being alive). I doubt whether most people nowadays realize how enormous and appalling a shock the Great War was - and was universally felt to be. With the possible exception of the Black Death, it was by far the greatest disaster which has ever befallen this country. Our losses alone — over a million dead - substantiate that. This is not the place to try to summarize the economic consequences or the blow to the British empire. (I have, in effect, lived in one continuing economic crisis all my life: you feel the difference at once when you go to America.)

On the first day of the battle of the Somme in July 1916, far more men were killed than can ever have been killed on any one day before. I remember reading that at the close of the Allies’ 1917 (Passchendaele) offensive, there was scarcely a family in England not mourning the loss of some member.

Within a few years, every village had its war memorial. Today they are often neglected - even defaced - and the people most impressed by them seem to be American visitors, who have more than once remarked to me on their ubiquity and the length of the lists of dead even in relatively small communities. The local names strike home - Tysons in the Lakes, Dyers in Somerset, Canes and Slococks in Berkshire. I particularly admire the memorial at Southend, Bradfield, Berks. This gives each man’s rank, name, regiment or arm, the place where he was killed or mortally wounded and the date when he died. I believe this to be unique.

My generation grew up in the shadow of the Great War. Before I was nine I knew virtually all the significant place names - Ypres, Albert, Thiepval, Bapaume, Delville Wood, Vimy Ridge and so on. As I grew older I came to realize that the world has not been the same place since that war. In what respect? In a word, a universal sense of insecurity. Before the Great War, British people for the most part trusted their leaders, were proud of their country and believed in progress. Not any more. The general notion that leaders (and experts) are not to be trusted on any account, and that catastrophe is ever at hand, goes back not to the atom bomb but to 1914—18. I absorbed it unconsciously as part of growing up.

I remember the Christmas morning service at St Nicolas church in Newbury. This was a full-scale civic ceremony, which always used to impress me (and everyone) deeply. The church, which dates from the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, is a very fine one, built for the most part with the fortune made by John Winchcombe, the wealthy clothier and wool merchant commonly known as ‘Jack O’ Newbury’. On Christmas morning, if you wanted to avoid being seated in some remote corner, you needed to be there in good time, for half or more of the nave pews on each side were reserved. A little before eleven the civic procession began. First came the Mayor, in his robes and chain of office, preceded by a mace-bearer. He was followed by the members of the Corporation, also robed, and the Mayor’s guests, such as Ann’s father, Mr Lester, head of the Newbury Waterworks, the squires of neighbouring villages, doctors of the hospital and any other local grandees the Mayor thought should be there. (My father used to be invited, but never went: I never once knew him to enter a church.)

Next came the British Legion, all in their medals and with two comrades detailed to present to the Rector their colour, to be laid on the altar. Several were disabled - blind or on crutches. After these followed a representative contingent, all in uniform, of every civic service; the police, the post office, the firemen carrying their shining brass helmets. A leash of nurses from the hospital would be there, conspicuous in white and blue. When everyone was seated Mr Majendie, the rector, would speak a few words of welcome and Christmas greeting and then we would launch into ‘O come all ye faithful’.

I recall someone else who deserves record - the barrel-organ man. The barrel-organ man didn’t come very often; perhaps once in eighteen months, or even more rarely. The barrel-organ itself I remember as a stout, solid affair - at least as big as a bath – mounted on two wheels like a gig, with its own shafts and covered all over in stout, grey canvas, so that all you could see of the works were the pointer to change the tune and the brass handle you turned to play it. It was pulled by a donkey.

The barrel-organ man would simply come to the front door and start up. To hear him, wherever you were in house or garden, was to drop whatever you were doing and come running out. He talked little - perhaps he was Italian - but he always smiled amiably; and he would allow you to try to turn the handle yourself. I say ‘try’ because I never could master the knack of turning it evenly and regularly. The tune came out in jerks: but not when he played. It was a beautiful, unique quality of sound, a metallic vibrato. I wish I could hear it again. I wonder what it would be worth now.

The proper thing to give a donkey, of course, is a carrot; and much scurry there would be to produce some; from the garden if it was summer, and from the loft if it was winter. The donkey ate them with relish. Its lips were pleasantly flexible, warm and soft. The barrel-organ man didn’t stay long. He took his hand-out and departed. I never liked seeing him leave. He was a rare treat.

I remember Mrs Griffin, the charwoman. Mrs Griffin looked poor as no one looks now. Her thick, black hair, which had certainly never seen a hairdresser, was fastened with hairpins in a bun at the back. She had no teeth and no false teeth. Her cheeks had a shiny, rosy colour - there was something a little gipsyish in her appearance - and she smiled a lot, to ingratiate herself, I dare say. She lived down in the town and used to come all the way up the hill on foot to scrub our floors. She scrubbed floors and she drank cocoa with her dinner and at the end of the day was paid half-a-crown. The job of taking it to her was usually delegated to my sister, who not long ago told me that she had never forgotten, in fifty years or more, Mrs Griffin’s mumbling, effusive delight over her half-crown.

I remember, and I am not likely to forget, Marian Hayter. Colonel Hayter and his family were patients of my father, and lived out at Burghclere, not far from Colonel Elkington. There were two girls, Elsie and Marian, and two boys, Anthony and David. Anthony and David were the younger, about my own age, while Elsie and Marian were some eight or nine years older - about the same age as my brother and sister. Later, in the ‘thirties, Elsie became an Oxford Grouper: and what happened to her after that I don’t know. Marian Hayter was, by common agreement, the most beautiful girl for miles around. She did teach the torches to burn bright. Since then I have had the luck to meet some very beautiful women (including Virginia McKenna, Julie Christie and Raquel Welch) but I have never seen anyone - anyone at all - more beautiful than Marian Hayter. She fairly knocked you flat (even at the age of eight or nine); a perfect English blonde, golden-haired, blue-eyed, smiling, graceful in movement, softly rosy, with a kind of unselfconscious vivacity and poise which made you want to go on looking at her for ever. She later married the chairman of the Rootes Group. Good luck to him!

Anthony Hayter was one of the R.A.F. officers who escaped from Stalag Luft III in the famous and desperate wooden horse break-out. As is well-known, Hitler, in flagrant breach of the Geneva Convention, personally ordered that all escapers caught should be put to death. Anthony succeeded in travelling across Germany as far as Strasbourg. Here he was arrested by the Gestapo, who drove him out into a nearby wood and shot him.

For an eight-year-old the prospect of leaving home for boarding-school was a daunting one. I have always felt that the idea was not put across to me in a properly positive way. I had known for years - ever since infancy - that one day I was going, but I had also known since about 1928 that the time fixed was the Michaelmas term of 1929. However, this was changed, at almost no notice, to the earlier summer term. I don’t know why, but I dare say it may have been a full quota of new boys already accepted, or something like that, which made my father agree to the earlier term. However this was not the reason given to me. The reason given to me by my mother was that I had become too naughty and uncontrollable. If I were the parent of an eight-year-old boy, I certainly would not give him such a negative and dispiriting reason for so big and important a step in his life, even if it were true. I would contrive somehow to put the thing across to him in a positive way and do my best to persuade him to accept it willingly. However, if my dear mother had a fault, it was a moody inconsistency of temper. There were times when one could do nothing right. I can’t remember what I’d done wrong when one day, round about the end of March 1929, she said ‘As you’re so naughty, I’ve decided to send you to boarding-school this term.’ Of course, it had all been fixed well before that: my trunk had been bought and lettered, and clothes, socks and handkerchiefs put up together in conformity with the school list.

I tried pleading and promises to reform. But the sight of the trunk and other things brought home to me that this was a fait accompli. I remember, during that April, a feeling of mounting apprehension as the days went by, but not much else to mark the end of childhood.

On the afternoon of the day on which I was to leave, I slipped out alone into the garden and made a kind of ceremonial peregrination round the whole place, saying good-bye to the stables and the loft, the ruined pigsty, the herbaceous border, the hundred-yard-long hornbeam hedge; and to Bull Banks. The coming term was to last three months, and I would never have been away from home for anything like so long before.

I remember actually handling the grasses in the paddock and murmuring some sort of farewell to them. It was appropriate enough. For the next ten summers I was not to see the tall grasses changing their burnish under the midsummer wind; nor to take part in hay-making.