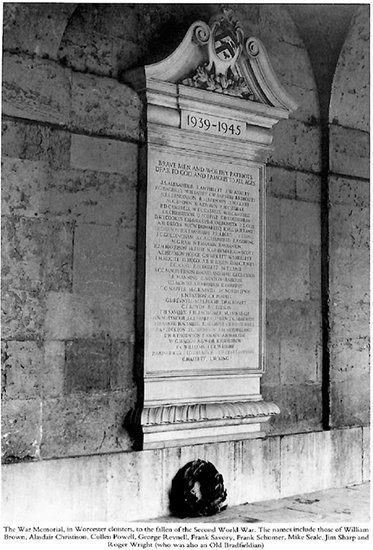

At this point, reader, there should be something in the nature of a caesura: an induction in the text, an arsis in the voice of the narrator. What is that proximate glow in the sky ahead? No, you need not suspend disbelief. We are, in cold truth and with no hyperbole of my making, approaching great excellence and splendour, common as sunrise, greater than Alexander and his hosts, more glorious, tragic and terrible than Troy or Byzantium: the fury and the mire of human veins.

When George Orwell wrote that in America in the mid-nineteenth century human beings were free as they had never been before, he meant precisely that. And I am about to write of the bravest men who ever lived. But at that rate, I suppose, I cannot avoid antagonizing readers who have themselves served with men whom they believe - know - to have been unsurpassed. So I will simply call the British Airborne Forces as brave, as great-hearted as any men who have ever lived. Some — I suppose - may have been as valiant, but none more so. I never heard them spoken ill of.

I was not one of those valiant: but I was with them in a subordinate capacity; I wore their uniform and - largely because criteria were not exacting in all the exigency, haste and commotion of the war - was never sent packing. My leaky, ill-trimmed little craft fell in with the most heroic and glorious fleet that ever sailed, and for two years it was granted me to limp along with them, at least tolerated and undismissed. You should have known them. I have never felt more proud, fulfilled or happy before or since.

‘There’s a posting in for you, to C.R.A.S.C., 1st Airborne Division.’ When MacLeod said this, my heart turned over in real apprehension. They had taken me at my word! I had for long insisted that I wanted to do it and at last someone had said ‘Very well.’ This was real. There was no going back on it now. The roller coaster had started and I was on it.

My trembling resolution was saved by two things, both of which I now know to have been illusions. First, at this time in my life, graded physically A1 as I was, I genuinely believed that what one man could do, another man, given the determination, could also do. Granted the physique, it was all a matter of purpose, will and intent. And I was determined all right.

Secondly, I supposed, with an inward qualm, that the discipline would be a prop and support. Presumably I was now on my way to a division in which firm discipline was the order of the day. I’d been in the Army for three and a half years, but no doubt I’d seen nothing yet.

I couldn’t have been more mistaken. There was unbounded group morale but very little formal discipline in Airborne Forces. If they didn’t like you, they didn’t waste time in discipline: they didn’t have to. They just got rid of you. They could pick and choose - officers and N.C.O.s anyway, and all parachutists, for they were volunteers. What I was going to find out was whether they wanted to keep me.

What was my real motivation? I can’t, in all honesty, say whether or not it was the same as everybody else’s, for truth to tell, one thing I have never heard talked about by parachutists is their motivation. There was a bit more pay but not a lot, and in any case I doubt whether anyone’s motivation can ever have been financial.

What had allured me from the start, back in 1942, had been the red berets and the flamboyant blue-and-maroon shoulder flash - Bellerophon riding on Pegasus to kill the Chimaera. These men must be a special band - couldn’t not be - for the authorities had conferred upon them a uniform to tell everybody as much. I coveted that uniform, that distinction.

But as 1942 and then 1943 wore on, I came to have another reason. On the whole I didn’t like the company I had to keep. Roy, Paddy and Piggy had been, of course, another matter - they were unique - but by-and-large I didn’t terribly care about my colleagues and in particular about my commanding officers. Other ranks, of course, differ little from one mob to another. As General Montgomery said, there are no bad soldiers, only bad officers. I’m bound to say, though, that on the whole the N.C.O.s in No. 2 Petrol Depot had been no great shakes. Like Kent, I had seen better faces in my time than any I beheld about me there.

I had come to believe that if only I could get into Airborne Forces, both officers and N.C.O.s would be of an altogether different quality. I proved to be entirely right: they were. But where did that leave me?

It was January and very cold after the Middle East. I made the usual slow, disagreeable rail journey northwards, and at the end of it reported to Divisional Headquarters at Fulbeck, some eleven miles south of Lincoln. With no delay at all I found myself talking to Lt.-Col. Michael Packe, C.R.A.S.C., 1st Airborne Division.

Within a few minutes I felt that I was breathing a new air. I need only say here that I got on very well with Colonel Packe, then and throughout the next eighteen months. After we had chatted for a time, he said he was going to post me to the Light Company -250th Light Company, R.A.S.C. (Airborne).

At this point I had better explain that, in those days at any rate, an Airborne Division’s R.A.S.C. (who were divisional troops) consisted of three companies - two heavy and one light. The two heavy companies (each a major’s command) were equipped with 3-ton Bedford lorries and did not differ essentially from any motorized R.A.S.C. company. Their job in action was to follow up an airborne attack together with the relieving ground troops, to bring in the division’s heavier equipment and then assist it in its ground role.

The light company was different in function and kind. It consisted of three parachute platoons and three platoons of glider-borne jeeps. Each parachute platoon was commanded by a captain, with a subaltern 2 i/c: the N.C.O.s and men were all volunteer parachutists. Their role in action was to drop with the division, and thereupon to have the responsibility for collecting and distributing all subsequently dropped supplies; medical, food, ammunition (and conceivably petrol). They might well find themselves required to fight for possession of these supplies: if, for instance, containers happened to be dropped outside the area controlled by the division, or if the enemy attacked the dropping zone. They were equipped and trained accordingly.

The three platoons of glider-borne jeeps were not volunteers, although in 250 Light Company everyone was positively motivated. (If not, they were posted.) The rules were that any soldier at all could be ordered to travel in a glider, but only qualified parachutists could be ordered to jump from ‘planes. Each platoon was organized in seven sections of about six or seven men, each under a corporal, and there were two sergeants to each platoon. The role of these platoons was to go into action with their jeeps in gliders (two jeeps to each Horsa glider) and then make themselves useful either in co-operation with the parachute platoons or as otherwise required by Divisional H.Q.

As I was to discover, the O.C. of 250 Company preferred all his officers to be parachutists, whether or not they were members of a parachute platoon.

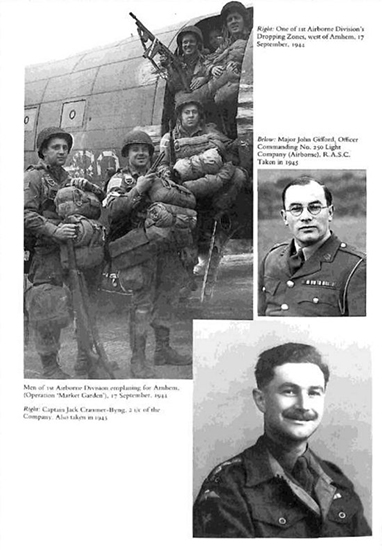

That same evening I was driven to Lincoln and reported to Major John Gifford, commanding 250 Company.

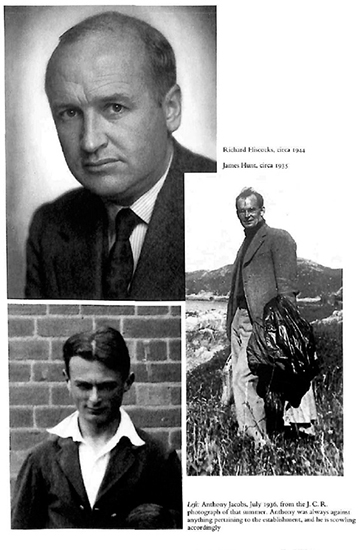

It would be wearisome - and not really helpful - to give a character sketch of each officer in the company. There were about twelve or thirteen altogether, and they comprised a very strong team, much stronger than any I had yet come across. Apart from that, collectively they have importance to this book, since later, from my memory, they provided the idea for Hazel and his rabbits in Watership Down. By this I do not mean that each of Hazel’s rabbits corresponds to a particular officer in 250 Company. Certainly the idea of the wandering, endangered and interdependent band, individually different yet mutually reliant, came from my experience of the company, but out of all of us, I think, there were only two direct parallels. Hazel is John Gifford and Bigwig is Paddy Kavanagh. I cannot really avoid a description of John Gifford - although he will hate it and may even be angry with me, though I very much hope not - because he has had as much influence on my life as James Hunt or Richard Hiscocks, if not more. Yet of all things he always hated any kind of flourish, ostentation or - well, bullshit; so I apologize to him.

John Gifford was at this time, I suppose, about thirty-three or four. He had been an architect in civilian life before the war; and he was a bachelor. He was about five feet nine inches tall and had a rather high colour and black hair. He was pleasant-looking without being spectacularly handsome, and he wore glasses. He moved well and had a quiet, clear voice which he never raised, except when giving commands on parade. He seldom exclaimed and he never swore.

Everything about him was quiet, crisp and unassuming. He was the most unassuming man I have ever known. When giving any of his officers an order he usually said ‘Please’, ‘Would you like to -?’ or ‘Perhaps you’d better -’. He could be extraordinarily cutting; at least one sensed it like that, because a rebuke from him was so quiet and so rare, and because everyone had such a high regard for him that you felt his slightest reproof very keenly.

He was an excellent organizer. One of his strongly held principles was that it was important to get the right person into the right job, and the wrong person out. This went right down to the level of Private. I had never consciously thought about this principle before (‘Anybody can do anything’), but I realized it all right after I had been under John Gifford’s command for two or three weeks, when he gently pointed out to me that the reason why my platoon administration was in such a mess was that Lance-Corporal Tull was entirely the wrong sort of person to be trying to do what I had told him to. Since then I have needed no further telling.

John Gifford was brave in the most self-effacing way. One morning a few months later, when I had learned my way around in the Company and knew what was what, I missed the O.C. at breakfast and, since no one else happened to be near by, asked the mess waiter, Ringer, if he knew where he was.

‘Oh, the Major went out early, sir. He heard last night that some of the gunners were jumping this morning and fixed up to join them.’

No one else knew about this. Jumping is a frightening and unpleasant affair. John Gifford was not in command of a parachute platoon, but he made it his business to do as many jumps as anyone else in the Company and to say nothing about it.

Turn-out was important in the Company, as throughout the whole Division. I recall that once a directive was included in Company Part I Orders that for the future people would not wear airborne smocks (camouflage jackets) off duty and particularly not in pubs. A couple of days later, I was with John Gifford and one or two other officers when we went into a local pub. The first thing we saw was my sergeant, Smith, together with two of my corporals, drinking at the bar; all were wearing airborne smocks. Nobody said anything, since the O.C. was the senior officer present and the matter was therefore at his discretion. John Gifford led the way to the further end of the bar and ordered a round. Next day, he happened to be looking informally over my platoon location when we encountered the sergeant, who came to attention and saluted. ‘Good morning, Sergeant Smith,’ said John pleasantly. ‘I hope your beer tasted equally good in airborne smocks?’ Nothing ensued. Having dwelt on this, I perceive that it was really a communication from one comrade to another. ‘Unfortunately I happen to have the job of commanding you: I’m sorry.’ That was how it worked on Sergeant Smith, too: he didn’t forget it. He did not.

Everyone in the Company was an individual, known by name and ability to the O.C. I remember now, particularly, the quartermaster sergeant, Greathurst. Greathurst was a personality in the Company, gentlemanly, light-hearted, buoyant and amusing, extremely good at his job, with a wheelbarrow full of surprises (as any good quartermaster should have) and his own little coterie of assistants, including Lance-Corporal Goodfield. Goodfield, amongst other things, was a brilliant pianist and, together with Greathurst, splendid company in a pub. Particularly memorable was their dual rendering, prestissimo, of ‘Susie, Susie, sitting in the shoe-shine shop, she sits and shines and shines and sits and sits all over the shop.’ (Anyone who got it wrong had to buy a pint.)

Sergeant-Major Gibbs was like a sergeant-major in a music-hall sketch. Almost illiterate himself, he was a veritable scourge on parade and would bawl out his victims mercilessly, until they, standing to attention before him, were deeply relieved to receive at last his customary conclusion: ‘Right! On yer way, on yer way! Outa me sight! Yer idle, yer idle.’ It once fell to my lot to read the first lesson on church parade, about the oppression of the Israelites in Egypt. This was from Exodus and included Genesis, Chapter V, verse 13. It was only our respect for the O.C. which enabled most of us to keep straight faces.

I remember John Gifford once telling Sergeant-Major Gibbs that he should communicate something or other in a letter to Div. H.Q. ‘Me, sir?’ said Gibbs. ‘Write a letter, sir? Got ’ighly trained staff do that, sir.’

After Arnhem, it was one Corporal Wiggins, rather than any of the officers, whose death John Gifford seemed to feel most keenly. We were all equal in his sight.

At one time the Company had wished upon it one Lieutenant Cordery, a big, burly man who before the war had a been a regular soldier in the ranks. Though not yet qualified as a parachutist, he was appointed as subaltern to Captain Kavanagh’s platoon. Cordery soon made himself unpopular. He was forever telling the men (he customarily addressed a man as ‘sonny’) that he was no war-time soldier; that if they thought they were smartly turned out then he, Cordery, could inform them otherwise; that he could show them hills in comparison with which they would call that a valley, etc., etc. ‘Oh, they must love him!’ remarked Kavanagh one day to John Gifford.

However, after a short sojourn, Cordery was no longer to be found among those present. He had been posted. No one said anything at the time, or during ensuing weeks. At least, I heard nothing. Much later that year, when we were in Normandy, his name came up.

‘Oh,’ said John Gifford, ‘there was nothing wrong with Cordery. He was just too good for us, that’s all. He was a soldier: we’re not soldiers.’

John was always very selective indeed about accepting officers into the Company. Anyone who came was very much on approval. Some time during 1944 we received a young officer called Dale, who was sent to me to see how he made out. Dale was keen as mustard: nothing was too much trouble for him. Perhaps - I think now - he may have been a little too eager for approval: I don’t know. One thing not his fault nor yet in his favour was that he was physically small - an unusually short man. My stated opinion to the O.C. was that, while Dale lacked charisma and was not likely to make people exclaim ‘Gosh! There’s an Airborne officer if ever I saw one!’, he was nevertheless a good little chap who deserved to be taken on. But John Gifford wouldn’t have it. ‘I don’t think we really want him, do you?’ he said to me in his quiet way. Now Dale, whatever his merits, was not worth contention with so experienced and able a commanding officer. So I knuckled under, and Dale disappeared too. I know he thought I must have reported against him: he was terribly hurt and disappointed. Still, I suppose John Gifford was right: he nearly always was.

I may have given an impression of a rather serious — even humourless - man. Nothing could be further from the truth. In the mess John was excellent company and most

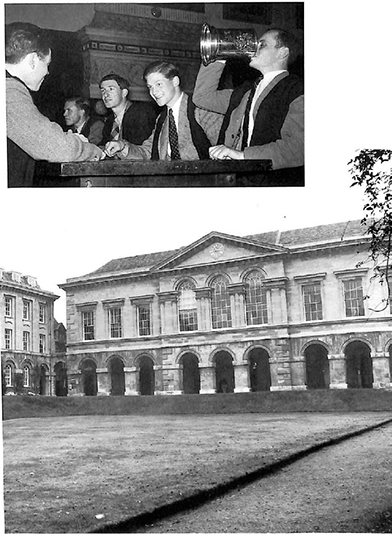

amusing, while always retaining that slight degree of reserve that a commanding officer must. I well remember our drinking parties, at which John often showed a predilection for a particular bawdy song, no doubt still in circulation, about Three Men of Nor-or-folk, Nor-or-or-or-folk, folk, folk. Terrible things happened to this trio. They all fell down a pre-ci-pice (pre-e-e-ci-pice, pice, pice) and had to go to hospitool, but there were no be-eds va-a-cant. John would join in singing this song with a kind of joyous gravity, as at the celebration of a rite. He drank his whack, but I never saw him the worse for drink. He was very fond of contract bridge, and there was nothing he liked better than a four. I was shocking bad - still am - but the M.O., Dr Willard, was good, and so was Phil Bushby, the Workshops officer. Once, at Nijmegen, we played bridge with the odd shell dropping from time to time. No doubt lots of other people have, come to that.

From the top of the Company to the bottom, the men all had the greatest liking and respect for the O.C., and it was only necessary to say to your N.C.O.s ‘The Major doesn’t like -’ or ‘The Major thinks we need to -’ for his will to be done without the least demur.

Captain Paddy Kavanagh was quite another thing. He was about twenty-nine and before the war had been a journalist. He was, of course, Irish, though he had no brogue.

Paddy was a sensationalist; by temperament entirely the public’s idea of a parachute officer; good-natured, debonair, generous, always in high spirits (I know John Gifford, despite his liking for him - you couldn’t not like Paddy - found him a bit much at times), a deviser of dares, afraid of nothing (including jumping), so it seemed. He once jumped with a kit-bag on each leg, to show that it could be done: another time he jumped with a large wireless transmitter. He had a bucko sergeant, McDowell, and the two of them used to get up to some rare old larks. Once, Kavanagh was going to make his platoon crawl under live fire from a Bren gun, and began by setting them an example. After about a quarter of a minute he called to McDowell, on the gun, to aim closer. Afterwards, they found bullet holes in his airborne smock. Another time, when he had his platoon out on the Derbyshire moors on a bitterly cold day in the winter of early 1944, they came upon a steep-sided reservoir. ‘Fancy a swim, Sergeant McDowell?’ asked Kavanagh. The sergeant looked at him and bit his lip. ‘I will if you will, sir.’ So the pair stripped off and plunged into the near-freezing water. Paddy was out first, heaving himself up the shelved walling. But Sergeant McDowell was below middle height, and what with the terrible cold, simply could not pull himself out. Instead of helping him, the platoon stood round laughing at him and he very nearly died in the water before someone gave him an arm. Sometimes Kavanagh and McDowell would take the pin out of a live grenade and toss it between them until one of them (‘Cissy!’) threw it down the pit or over the wall.

John Gifford’s quiet certitude, however, was always finally a match for Paddy, as Hazel’s was for Bigwig.

I recall one of my own men, Driver Fisher, saying ‘I’d like Captain Kavanagh to train me, but I’d hate him to take me into action, because I’m sure he’d kill me.’

The evening I joined the Company, I went out drinking in Lincoln with the O.C., Kavanagh and one or two more. I don’t know whether or not I was being looked over, but they couldn’t have been nicer: Kavanagh was perfectly charming, as a matter of fact. I remember seeing some Other Ranks near by, with their red berets pulled under their shoulder straps, and that I asked Paddy whether that was the thing to do. ‘Well,’ he replied, ‘we don’t quite do it.’ (Meaning officers.) He could have said ‘Good God!’ etc., couldn’t he? That evening I was treated like a guest and no one asked me anything military at all; but somehow I felt confident. This was the new deal at last.

Next morning John interviewed me formally in the office. ‘How do you feel about jumping?’ he asked.

‘I want to jump, sir.’

‘Well,’ said John, ‘we can see about that. There’ll be time. But I think an officer of your experience should have an independent command, rather than being subordinate in a parachute platoon. I’m going to give you C Platoon.’ (This was one of the platoons of glider-borne jeeps.)

Oh, C Platoon! Reader, please forgive a brief rhapsody. Was there ever such a platoon - was there? What a plague could I do for C Platoon that they couldn’t have done without me? That wasn’t quite true, actually - there has to be an officer, or things start getting wugular - but jolly nearly. Both the N.C.O.s and the men were beyond the wildest dreams of any subaltern. They were not only extremely competent - Sergeant Smith (Gerry) was a great deal more competent than I - but splendidly keen and very diverse. From Corporal Bater (Devonshire) - whom I have personally seen drink sixteen pints in an evening and then drive a jeep (I was in it) - to Corporal Herdman (‘Wheel him in, ah ha ha ha!’), a Geordie, there wasn’t a dud in the lot. Well, of course, there couldn’t have been, not in 250 Company, only I just wasn’t used to that sort of style, see? Even the Lance-Corporals (Barnard and Rushforth) would have made damned good corporals anywhere else. And when I start remembering the men individually - Eggleton, Fisher, Williams — well, a reader is bound to feel this tedious; but don’t forget that I’m not the first writer to have found commanding a good platoon the most fulfilling and rewarding thing they have ever had to do. Herbert Read, for a start. And Robert Graves and - a whole lot more. I wish I were back there, straight I do.

The first thing C Platoon had on their plate after I’d taken them over was to go to Wellington, in Shropshire, and collect forty jeeps and eighty trailers - to make us effective according to establishment. Now airborne trailers were tricky things. Towing one empty one behind you was dangerous: towing two was even more dangerous. If you went too fast, the empty trailer might well turn over, and if it did, then the open-sided jeep went over with it. I have known at least one man (not mine) killed in this way. With two trailers per jeep, we had to drive back from Wellington to Lincoln at no more than twenty m.p.h. all the way.

The evening we got to Wellington was actually the evening of the day on which I had taken up command of the platoon. I asked the N.C.O.s how they intended to pass the evening and they said they were going out on the beer. I immediately asked whether I could come along, and of course they said Yes: they couldn’t say anything else, really, but I saw an apprehensive shadow cross a few faces. They thought I and my pips were likely to be a drag on the evening. I knew that it was vital for the future of our relationship that I should join them and that in the course of the evening they must come to decide that they liked me without, at bottom, losing respect for their new officer. Well, it worked. It was really that they liked themselves and their red berets so much that they were essentially good-natured and well disposed. They liked being who they were, they liked what they were doing and they liked being under the command of John Gifford. They felt no resentment against the army or against the set-up they were in. As the pints took hold and Corporal Rawlings talked to me of how the company had been formed, in 1942, under the command of Major Packe, and of what they had carried out in North Africa, Sicily and Italy, I felt even more fully committed to what we were doing and to trying to be an airborne officer. I had never dreamt that there could be a platoon - or a company - like this. They should have every scrap of me, twenty-four hours a day. I honestly believe that the N.C.O.s went to bed that night feeling that the new officer at least liked his beer, had a sense of humour and might turn out to be not too bad.

As for the men, there was none of the peevishness, shoulder-shrugging or ill-concealed resentment with which I had become all-too-familiar elsewhere. Neither was there any of the kind of spirit expressed in ‘We are Fred Karno’s army, we are the A.S.C.’ They did not regard themselves as Fred Karno’s army. They were glider-borne troops of the 1st Airborne Division: Hitler had a nasty shock coming. I don’t mean that they had no sense of humour, or that I didn’t get my leg pulled in all the minor and time-honoured ways. But none of them ever ran down the Company or the Division. (‘’Wish Ah was out o’ this f— lot.’ To which the answer would have been ‘Well, you can go tomorrow morning — easily. Your passport shall be made and crowns for convoy put into your purse.’)

With everyone in this frame of mind, of course, the role of the platoon commander became according. You could treat the men with semi-familiarity. You didn’t have to drive them. You didn’t blast people, threaten them or put them on charges. (If there was one thing John Gifford hated like poison, it was a charge. ‘Couldn’t this have been avoided?’) On parade I reproved mostly by mock, histrionic severity. ‘’Orrible man!’ became a platoon catchword. Lady Godiva reappeared, and another crack I had acquired from somewhere. ‘I will not have this place left looking like a Chinese revolving shit-house!’ In Tunisia they’d all picked up the Arabic, of course - Maaleesh, stannah shwire and so on - which at that time was still a sort of initiates’ language. With a platoon like this, all you really had to do was try to work still harder than they did, prevent them from being buggered about by anyone else (outside the company, I mean), appeal to their self-respect when necessary and take every opportunity to set an example: get the first needle-jab, be the first man up in the morning, change a flat tyre with your own hands and generally have a bash at anything that offered. When in doubt, ask yourself what Gifford or Kavanagh would do. Given youth, health, energy and enthusiasm, it was simple.

Anyway, I know it worked (relatively) because since the war I have talked to demobbed people who were on the receiving end and are now free to say what they thought.

An example of what zest and esprit de corps can do to your metabolism was the cross-country. The cross-country was John Gifford’s idea. He devised a course of about four miles over the rural western outskirts of Lincoln and gave orders that everyone would participate - clerks, medical orderlies, mess waiters - the lot. Now I had never been any good at running. At Bradfield I used to stagger round on appointed afternoon runs with less than no enthusiasm, and had been only too delighted when being a fives colour had got me out of the senior steeplechase. But this was different. I knew there were some very rapid people among both the officers and the other ranks. I suspected that I might well be still on approval. Somehow, I had got to do creditably. With an effort that nearly killed me I came in sixteenth. (John Gifford himself was eighth and Paddy fifth.) C.S.M. Gibbs was the only man excused: I think it was thought that it would excite risibility and be bad for discipline if he appeared puffing and blowing with a place in three figures.

As spring drew on and the unknown date of the invasion of Europe (D-Day) came closer, airborne activities began hotting up. I was sent to some local aerodrome or other to get glider experience, and spent a couple of wonderful days flying from somewhere near Lincoln down to the south coast and back, as theoretical co-pilot in a Horsa in tare (empty). The real pilot was a delightful chap and I learned a lot from him about how to be helpful to glider pilots and what not to do in a loaded glider.

Then C Platoon went to Hope, near Edale in the Peak District of Derbyshire. ‘Edale’ was a particular private wheeze of 1st Airborne R.A.S.C., the invention of Major David Clark, 2 i/c C.R.A.S.C. David was a hell of a goer, one of the most rugged, stalwart officers in the Division. He had been an amateur county cricketer (Kent) and he could cover steep, mountainous ground for hours at almost incredible speed. (Late on, in 1945, when he was among starving prisoners in Germany and being marched backwards and forwards between the collapsing fronts, David was an inspiration and a hero, whose compassion and endurance saved many lives.)

David had devised a week’s mountain ‘course’ at Edale, to toughen the blokes up (and half-kill some of them). All platoons (including those of the heavy companies) were sent on this course in turn. It was a good racket for David, since he lived in two rooms at the New Inn, and administered the course - when himself not out on the tops. Mr Herdman, the landlord, was also a keen walker, beer drinker and singer of songs; he couldn’t have had a more congenial guest and companion than David, and of course a steady succession of thirsty airborne soldiers in large numbers was exactly his ticket.

I reported C Platoon to Major Clark at about four o’clock on an early spring afternoon. He was in what I can only call his parlour at the New Inn. ‘Hullo, Adams,’ he said. ‘Do you like Delius?’ I said I did. ‘Sit down for a bit, then.’ It was, as I remember, A Song of Summer. It seemed appropriate.

That was a week and a half! The platoon climbed Kinder Downfall (yes, they did), with the help of one or two ropes put up by David; walked miles all over Kinder Scout in battle equipment; did a grisly night exercise in which all N.C.O.s had to use prismatic compasses; and in between whiles drank Mr Herdman’s beer in gallons. One night at Edale there was a dance, with the local girls brought in lorries (illegally authorized by David). At about ten o’clock he, Sergeant Smith and I were drinking in the bar when David said that for two pints he would now, personally, go out, climb the top that stands north of Edale (1,937 feet) and be back in fifty minutes. He did so. (He said he’d done it and no one dreamed of doubting him.)

Another day, I had to take the platoon on a fairly wearing walk (it wasn’t a march: we went by sections, I think) over the tops. We reached our destination at about half-past two, where we lunched on haversack rations, after which the men were free to laze about until lorries came to take them back.

A Kavanagh-esque idea occurred to me. ‘I’m going to walk back,’ I said to Sergeant Smith and Sergeant Potter. ‘Care to come too?’ They said they would not. I put it to the platoon as a whole. Only two people felt like coming: Lance-Corporal Rushforth and Driver Williams. So we set out.

Well, it was a sod: I don’t say it wasn’t. But we did it —just. Williams, a nice lad, was first class: he covered the distance without distress. It was poor old Rushforth who really suffered: I remember we pretty well had to help him down the last stretch, a steep valley known as Golden Clough; but he was game all right.

I left Edale with a very proper sense of my own limitations on Kinder Scout. You see, I had always hitherto had a good notion of my abilities as a walker, based on my childhood on the Downs, my ramblings with Alasdair in the Trossachs and so on. Before going up to Edale I had even felt impatient and begrudging of David Clark’s reputation in 1st Airborne R.A.S.C. The outgoing lot before us was one of our own para. platoons, Captain Gell’s. I remember saying fatuously to Daniels, their subaltern, ‘What’s so marvellous about Clark, anyway? Can’t any fit bloke walk on the tops?’

Daniels, a big, husky fellow, paused for a few moments. At length he replied ‘You seen him go?’

A week or two after we had come back to Lincoln, it became noised abroad that there was to be old utis. General Urquhart, the Divisional Commander, was coming to inspect 250 Company. Apart from being the Divisional Commander, Urquhart as a man enjoyed the sort of esteem you’d expect. An officer of the Highland Light Infantry, he had been on the staff of 51st Highland Division in the Western Desert, and had taken over 1st Airborne after the previous commander, General Hopkinson, had been killed by enemy fire in Italy in 1943. He was known to be completely fearless but to hate gliding, which made him feel sick. As a rule, of course, he concentrated his attention on the six parachute battalions and three glider-borne battalions of infantry which were the fighting guts of the division, but naturally his gunners, sappers, signals, R.A.S.C. and other brigade and divisional troops also needed looking over from time to time.

John Gifford was not the sort of O.C. to be put in a tizzy by inspections from anybody at all, but nevertheless a divisional commander’s visit had to be taken seriously. Sergeant-Major Gibbs was given carte blanche, and for days his roars of rage and disapproval could be heard from North Hykeham to Washingborough. C.Q.M.S. Greathurst, an instructed scribe, brought forth out of his treasure things new and old. Chinese revolving shit-houses were swept and garnished within an inch of their lives. When the great day came C Platoon, in their rather isolated, Nissen-hutted, jeep-ranked location at North Hykeham, were ready for anything: not a boot-eyelet unpolished, not a Pegasus out of alignment.

We had a watcher out at H.Q., of course; it was Corporal Pickering, who came duly zooming back on his motor-bike. The General had arrived, and the O.C. had given him, Pickering, a nod that he meant to bring him up to C Platoon. In our apprehension was mingled real pride. With the whole company to select from, Major Gifford had decided to take the General to C Platoon.

The cortège duly arrived and Urquhart, a dark, big-built, hefty man, got straight out of his car and walked ahead into our location as Corporal Simmons slammed the turned-out guard into the present.

‘Where’s the platoon commander?’ he asked.

I found myself walking with him easily away from the Div. H.Q. retinue. Alone together, and amicably, the General and I strolled round the location. We chatted. I realized he was not looking for faults. This was a different sort of inspection.

‘What are your problems?’ he asked.

I couldn’t even invent one for him. I showed him a few patches of damp, and that was the best I could do. I introduced two or three of the N.C.O.s, who told him they were as happy as larks and ready to take their sections anywhere.

General Urquhart had not come to carp or to pick holes. He had come to inspire trust and win our confidence. He did that all right. He left after about twelve minutes, telling John Gifford that we were first-rate, or words to that effect. It was, as you might say, anti-climactic. Later, in the mess, John remarked quietly ‘I’m glad the General seemed pleased.’

It must have been about a week after General Urquhart’s visit that Paddy’s platoon, one morning, were jumping at a near-by airfield. Lincolnshire was full of airfields. On the flat land south of Lincoln, east of the Grantham road, they were laid out side by side like Brobdignagian tennis courts. It was from these that the hosts of Lancasters, Stidings and Flying Fortresses used to set out to bomb Germany. We grew accustomed to seeing hundreds deployed in the sky, manoeuvring into position before their departure.

An airfield, ready-cleared, makes an excellent dropping zone (D.Z.). A morning’s activity for a platoon - nothing in it, really, as long as it’s not you. Someone had mentioned to me that Paddy and Co. were jumping, but I hadn’t given it much attention, being too busy with C Platoon’s rifles. We’d just been told that all rifles which weren’t accurate in the aim were to be handed in. About mid-day I had come down to Company H.Q. to talk to C.Q.M.S. Greathurst about this matter, when I ran into Sergeant-Major Gibbs.

‘You ’eard, sir - we ‘ad a man killed this morning? Private Beal.’

The way he said it, it sounded like ‘Private Bill’; almost like a joke. It was no joke, however, but, like all fatal accidents, a horrible business.

What had happened was this. There were at this time two methods of jumping; one standing up, from the port rear door of a Dakota (C.47), and the other - the first-devised, original way -sitting down and propelling yourself feet forward through an aperture in the middle of the floor of a Whitley bomber. (‘Jumping through the hole’, as it was called.) Twenty men could jump from a Dakota, but the complement for a Whitley was only eight.

For a ‘stick’ of eight men to jump correctly required cool heads and accurate counting off. Sitting sideways on the floor and inching forward, each man in turn had to swing his legs and body through a right angle into the hole, and then push himself off to drop through it. There was a song (to the tune of ‘Knees Up, Mother Brown’):

‘Jumping through the hole,

Whatever may befall,

We’ll always keep our trousers clean

When jumping through the hole.’

I have never jumped through the hole, but John Gifford told me once that, in comparison with a Dakota, you got a much more frightening view of the ground rushing past below.

Normally two containers, each with its own parachute and filled with arms, ammunition, etc., were fastened under the body of the ‘plane and released by the pilot to drop in the middle of the stick (to ensure the best possible accessibility on landing). When the green light came on, the whole stick used to shout aloud as they jumped: ‘One, two, three, four, container, container, five, six, seven, eight!’ With number eight out, the despatcher would shout to the pilot ‘Stick gone!’ This is why old airborne soldiers still sometimes talk about a ‘container-container’ when they mean a container (e.g., in Marks and Spencer’s or somewhere like that).

A man on a parachute has, as many people today have seen for themselves, a good deal of directional control. Containers, being inanimate, exercise none. What had happened was that poor Beal, jumping number four, had had a container dropped immediately after him (and therefore above him). The container, oscillating on its parachute, had bumped into Beal’s canopy and collapsed it, and he had fallen to his death.

The incident cast a gloom over the company for several days. Many, many years later, when I was on the Great Barrier Reef off Australia, I met Arlene Blum, the American girl who led an all-woman expedition to climb Annapurna in 1978. Among other things she said to me was ‘What I learned on Annapurna is that you can be well-equipped and well-trained and do everything properly, and you’re still in horrible danger.’