Given the tremendous circumstances of the time, nothing could have been more quiet and uneventful than the crossing of 1st Airborne’s ‘seaborne tail’ to Normandy and our setting up camp in the bocage a good long way behind the British lines. Not a shell, not a German fighter came our way. In fact, the only incident of our crossing that I now recall is of an undramatic nature. 250 Company, minus its parachute element, was drawn up for embarkation on one of the Portsmouth ‘hards’, standing easy and rather detachedly watching a young naval officer bringing a destroyer up to the quay. You could see him, looking fidgety and nervous, on the bridge. He brought the destroyer in too fast and at too sharp an angle: the port bow struck the concrete with force. But she was going so fast that she went ahead for several yards, and the young officer had no recourse but to take her round the basin and bring her up to the quay a second time. This time, however, she struck the concrete even more bow on, and fetched up shuddering and stationary. At this moment one of her A.B.s - Sailor Vee, no doubt - somewhere below decks, stuck his head out of a porthole, looked genially round at the world and enquired ‘’Oo’s doin’ this lot, then: Errol fucking Flynn?’

We pussy-footed our jeeps to the Normandy beach along one of the floating causeways of the impressive ‘Mulberry’ harbour and soon after found ourselves in camp not far from Bayeux. Although there was as yet not a lot to do and not a lot to see except for the partly-tidied-up wreckage of the early battle-fields, we were all strung up to a pitch of excitement which even the coolness of John Gifford couldn’t altogether dispel. The division was going into action at last! We had grown tired of khaki-bereted louts outside pubs. at closing time shouting ‘Yah! Airborne - stillborn!’ and similar witticisms. 6th Division had been the flower of the invasion; we felt sure we were to be the flower of the final victory.

I had quite a bit of swanning around to do - locating supply-points and so on. I recall my driver, Farley, soundest and steadiest of Worcestershire swede-bashers, staring rather doubtfully at a crossroads Calvary (‘One ever hangs where shelled roads part …’) and asking ‘That s’posed to be Jesus Christ on the cross?’ ‘Yes,’ I said. ‘They have them like that here. We’ll be seeing a lot more.’ We were on our way to Saint-L6. When we came in sight of it I felt bewildered and overcome. There was nothing to be seen which could be called a town or even the ruins of a town. There was no longer anything, anywhere, recognizable as a building. Saint-L6, many, many acres in extent, was nothing but a locality strewn with wreckage and fragments. There were no soldiers there, either. General Patton’s tanks were already far to the south, forty miles away near Avranches.

I found time to go and see Bayeux Cathedral - the first European cathedral I had ever seen. After English cathedrals, the first impression it made on me was of being cluttered with paltry Popery props, which got in the way of the architecture and of the honest Protestant visitor. All the same, I admired its splendid thirteenth-century Gothic (wishing Hiscocks were there - ‘the real significance, er, Adams -’), the western towers and the apsidal chapels round the choir with its lovely carved stalls.

This was the time during which the Allies were holding the Germans where they were by close engagement south of Caen (Hitler himself was holding them there, too, for their commanders, von Kluge and the others, would have liked to pull them out), while the Americans, under Patton, broke through in the west at Avranches and then turned eastward to encircle them. On 20 July there had taken place the abortive assassinative bomb plot, when von Stauffenberg and others had tried to blow up Hitler at his headquarters in East Germany. As everyone knows, it didn’t work. That passed us by, really: since it hadn’t worked it didn’t matter. Only a few old desert veterans couldn’t help feeling ambiguously and paradoxically sorry for Rommel, who had been arrested and compelled to shoot himself. We somehow felt he deserved a better end: he was too good for Hitler, really.

All this time there were continual abortive stand-by orders for 1st Division. The division was going to drop to the south of the Germans, to the east of the Germans - anyway, on top of the Germans - at Argentan, at L’Aigle - God only knew where. But as fast as these various plans were made, the military situation would overtake them. John Gifford and the Jontleman never knew where they were from day to day. The plans came so thick and fast that we couldn’t help feeling some of them must be a bit half-baked. We were to find out that they certainly were.

It was mid-August when the German crack-up came in Normandy. Largely owing to Hitler’s refusal to let them pull out in time, hundreds of thousands of German soldiers, together with their guns, tanks and lorries, were trapped along the line of the Falaise-Argentan road and its environs. The magnificent Polish armoured division had made a dash and sealed off the eastern way out at Chambois and the upper valley of the Dives. Some broken German units had managed to escape, and they were going hell for leather all the way back to Holland. And still 1st Airborne had had no part to play, waiting near their airfields in England to strike the blow which would finish the war.

It so happened that about the end of August Farley and I, on some mission or other, had to drive down the Falaise-Argentan road: some fifteen miles, It was very bad indeed — too bad to attempt to describe. William Golding, author of Lord of the Flies, The Inheritors and the others, shows a preoccupation with what happens when a society - or just a man - goes beyond the point of disintegration. He should have seen the Falaise pocket. Auden hadn’t yet written his great poem ‘The Shield of Achilles’:

‘Column by column, in a cloud of dust,

They marched away, enduring a belief,

Whose logic brought them, somewhere else, to grief.’

Well, here was the ‘somewhere else’, after ten or eleven years of the belief. I’ve never seen a place after an earthquake, but it might look like that. There was no artifact whatever to be seen, large or small, which was not in fragments. No doubt there were mothers and wives now weeping for these horribly bent, stilled, waxen-faced men, but it wasn’t our fault. They had set out to kill us if they could. The smell reached you in intermittent waves, rather like azaleas across a garden.

Well, then it came time to follow up, along with 2nd Army’s pursuit. And, my God, did we move? 1st Airborne might drop at any time - only the High Command knew when - and its seaborne tail was required to be in the van, close behind our tanks and infantry. We crossed the Seine on a Bailey bridge at Vernon, and after that it was simply a question of keeping going night and day. Sleep when you can, eat when you can. I got so sick of spam that I could be really hungry and still unable to face another plate of it. The cheering villagers were generous with their apples. I remember our column halting for a time on a road beside which two elderly Frenchmen, watched by others, were sitting and playing chess while observing themselves being liberated. I got out of my jeep and began watching too.

‘Voulez-vous jouer, monsieur? Allons, je vous en prie.’

So I sat down to play. I got White, and opened P-Q4, followed by P-QB4. There were mutterings.

‘Gambie de la reine!’

‘Oui, oui; gambie de la reine; il sait bien jouer.’ (Dear me!)

We had to move on, of course, before the game was finished. But what a pleasant and - er - liberating thing to happen!

Gisors, Beauvais, Breteuil, Amiens, Doullens, Arras, Tournai in Belgium and still never a German. About 150 miles - no real distance today, of course, but hard going in the stop-start conditions of thousands of vehicles on a narrow axis of advance. The columns threw up such dust as I’d never seen since my infancy before tarred roads. As you sat waiting, with engine idling, to go forward, motor-cyclists riding the other way would flash up out of the dust and be gone three feet from your elbow.

It was one wet nightfall somewhere short of Ath, on 2 September, when John Gifford told me that the reserves of canned petrol we were carrying with us had grown very low. The advance had been so hectic that we had outrun any close source of supply. Every unit around was short of petrol. The nearest place where Airborne Forces were holding any quantity was in the neighbourhood of Doullens. Doullens lies between Arras and Abbeville, about sixty miles from where we were. John asked me to take C Platoon, go to Doullens and bring back as much petrol as possible.

We set out, the men driving the jeeps, the N.C.O.s on their motor-bikes. It was pitch-black - no moon - and of course we could use no lights. The wind was blowing hard and the rain was like a monsoon. There were many other groping vehicles on the roads. I was the only person in the platoon who had a map. It was all that could be done to keep our convoy together. At each road junction, either Sergeant Smith or Sergeant Potter would wait to direct the jeeps and count them all past. Every half-hour I halted the column for the section commanders to report to me that all their men and vehicles were in order. If this sounds over-zealous, you might try it one night: forty light vehicles, each with two trailers, no lights and no guide, in rain and darkness along roads you don’t know, in a foreign country. I had never before felt so helpless as a platoon commander. You couldn’t get to the blokes to talk to them, the N.C.O.s were soaked through and chilled to the bone and you couldn’t share it with them because somebody had to drive in front and read the map. It seemed to go on for ever, and the blackness was full of strangers and tumult. We heard rushings to and fro, so that sometimes we thought we should be trodden down like mire in the streets. And coming to a place where we thought we heard a company of fiends coming forward to meet us, we stopped, and began to muse what we had best to do. Well, Christian made it all right, but God alone knows how all those jeeps contrived to suffer not a single accident or breakdown. (If there had been one, of course, we’d have had to leave the driver with his vehicle.)

It took us a little less than three hours to get to Doullens; pretty good, I thought. Then we had to find out where the petrol dump was, for John had been unable to get a map reference. Farley and I were obliged to leave the platoon closed up and halted, and set off to find someone to ask. I wondered bleakly whether I ought, like Theseus, to be trailing a thread behind me. Would we ever be able to get back to them again? After a few minutes, however, we had the luck to spot a Pegasus directional sign beside the road, and not far away was the dump.

The platoon drove onto the heavy wire mesh doing duty for tracks surrounding the dump. Those who weren’t wet through already were able to put it right now, for we had to get out and load up. We all had army groundsheets, of course, but anyone who has worn one in a steady downpour knows how little comfort they really were. The blokes loaded, the N.C.O.s loaded, I loaded. We crammed every jeep and every trailer as full as possible with petrol. (By this stage of the war they were British jerricans.) The corporal in charge of the dump asked me into his tent to sign the necessary papers, although he said it didn’t matter how much we took. At length we were ready to return.

Going back was much the same, except that everyone was very tired, and hungry as well. We reached the company location - a field much like any other - and the platoon off-loaded the cans while I went to report to John Gifford. I felt we’d done rather well.

‘How much did you get altogether?’ asked John.

I told him.

‘It’s not enough.’

‘Sir, every jeep and trailer was bung full.’

‘Well.’ John paused. ‘You’d better go back and get some more.’

‘Now, sir?’

‘Yes, please.’

I went back and gathered the N.C.O.s. They took it very well. They were a fine platoon but, setting that aside, I was beginning to wonder how much more they could, physically and mentally, do. Mere endurance was not enough. To drive a jeep and trailer in convoy you had to be reasonably alert, and more than reasonably in these conditions. Well, we would find out. I was clear about two things. To read the map and find the way was my responsibility and I dared not delegate it. It couldn’t be done properly on a motorbike. But, secondly, I didn’t think the N.C.O.s could go on safely riding motor-bikes much further. We might perhaps be able to manage with fewer, but some motor-bikes there obviously had to be. How few? Sergeant Smith thought five. I reckoned six. I asked the assembled platoon whether anyone thought he had the know-how to ride a bike in these conditions. One man volunteered. He was very young, a boy named Driver Sutton. I want to put it down here that Driver Sutton did everything a sheep-dog motor-cyclist ought to do throughout the whole of that nasty journey. He was excellent.

That left five other motor-bikes and a total of nine N.C.O.s. Sergeant Smith worked out some sort of turn-and-turn-about system to give everyone a stand-down during the trip, and off we set again.

It would be tedious to prolong this account; but we got there, loaded up and started back without accident. I was beginning to feel a sort of affinity with Captain Cook. That was the whole point - that he didn’t have an accident - or only one, anyway. He must have had some first-class subordinates, don’t you think? I recall two things about our return journey.

During the first run, we had all perceived along one length of the very dark road a vile smell - the smell of corruption. As we were coming back from the petrol dump for the second time, the rain gradually stopped and light came into the sky. We were now able to see what it was that was nauseating us. The adjacent fields were full of dead horses; cart-horses, most of them. Our Typhoons had destroyed all the Germans’ motorized transport, and in their retreat they had commandeered horses and carts for their gear. But the Typhoons had got them, too. They looked so pathetic and pitiable, those great, innocent beasts, their legs sticking stiffly up at all unnatural angles and foul white bubbles blown from every orifice of their bodies.

We were just getting over this when suddenly Driver Farley said (just like a policeman) ‘’Ullo, ’ullo, what’s this?’ He had seen quicker than I. Three figures in uniform were approaching us down the slope of a field. They were Germans, evidently bent on surrender. We pulled up and I gestured to them to come up to me.

One was Luftwaffe. He looked like a veteran and turned out to be one, for I found in his pocket an iron cross (made of plastic) which bore the date ‘1939’. He also had a picquet pack which I’ve still got. The second was an infantry officer in jackboots, a mere child who looked about seventeen. The third was a Kaporal, black-haired and dour. I motioned them into the jeep and, when we came to the next small town, handed them over to the Maquis, in accordance with standing orders. That was the last we saw of them.

When we finally got back, the company had already up and gone. John had left someone behind to tell us where. The going was easier that day, even though we were all so sleepless; there seemed to be less on the roads. We caught up and that morning were among the first Allied troops to enter Brussels.

Guards Armoured Division, the spearhead of the Allied pursuit, reached Brussels on 3 September. Hard on their heels followed the ‘seaborne tail’ of 1st Airborne Division, ready to go forward as soon as the airborne attack on Holland should begin.

I have been told that the liberation of Paris had nothing on the liberation of Brussels, and I can believe it. Every street was thronged with people, laughing, weeping, cheering, climbing on our jeeps and lorries, covering us with flowers and paper-chains, pinning red-black-and-yellow emblems and boutonnières on our airborne smocks; girls by the hundred kissing us, men pressing upon us glasses of everything you can imagine. (‘M’sieu, voilà, le vrai Scotch whisky! Pour ce jour je l’ai caché quatre ans! Vive l’Angleterre!’) Everywhere the bells were ringing, bands playing. It was unreal — dream-like. I found, somehow or other, in my jeep, a pretty Belgian girl of about my own age - twenty-four. Her name was Janine Flamand, the daughter of (I think, having visited her home) a rather wealthy wine merchant. As we rode on, something amusing occurred which showed up my rotten French. The jeep was moving jerkily, as best it could, through the clamouring benediction, when Janine suddenly cried ‘Oh, j’ai perdue l’équilibre!’ In all the hubbub I heard it phonetically as ‘lait qui libre’, and wondered what on earth free milk could have to do with all this. I knew they were all ‘libre’ now, but the ‘lait’? An idiom? Anyway, Janine got liberated good and proper. During the next ten days - and later - I had quite a lot to do with the Flamand family and liked them very much.

John Gifford, while certainly no killjoy, sat a bit loose to all this wild melarky. It was not only that he had the Company to be thinking of. It was, rather, that this kind of rapturous frolicking and emotional carousal with strangers wasn’t compatible with his naturally impassive, self-possessed temperament. I have a memory of our being together one evening in some sort of club or dance-hall, with a band. We were continually being importuned to dance, of course, and John obliged with the best of them; but after a while the band struck up a conga. The conga of those days was an affair simple to the point of childishness. Everyone formed a line; you held the girl in front of you round the waist and the girl behind you held you round the waist. There might be a hundred or so people thus engaged. Then the chain cavorted rather ponderously round the room, flinging out right and left legs alternately as they went. I recall watching John’s back, four places ahead of me. It looked what you’d call unco-operative and long-suffering. Later that night, when we were out of the city and snugly back in our village near Louvain, he pointed to the brightly coloured wooden Belgian emblem pinned on my shoulder and said quietly ‘I think we’ll take these things off, shall we? We’ve liberated Belgium now.’

We were comfortable enough in that village, hearing and discounting military rumours; getting the vehicles - and ourselves - to rights after the rigours of the advance from Normandy; the blokes going into Brussels in relays for rest and recreation - rather more of the latter - and at last receiving letters from home. I found I could generally communicate what I wanted to in French, but understanding it was more difficult, because the locals spoke so idiomatically and quickly. The officers’ billets were in a friendly farmhouse. I remember that one early afternoon it began to rain heavily. After a minute or two Yvette, the grown-up daughter of the house, came running in with her hands and shoes dirty from the garden and poured out to me a torrent of urgent French. ‘Lentement, mademoiselle, je vous en prie: plus lentement!’ Yvette, hopping from foot to foot and drawing in her breath with hard-won self-control and patience, said ‘Les fenêtres’ — (nod) — ‘de votre chambre’ - (nod) - ‘sont ouvertes’ - (nod) - ‘et la pluie -’ The franc dropped, and I was half-way up the stairs.

Phil Bushby, our Workshops officer, was a much better linguist, and in the evenings used to read the local newspaper to get a bit of atmosphere. I recall him, after dinner one evening, reading out from the ‘Wanted’ column: ‘“Bonne serieuse”: how would you translate that, John? “Steady girl”?’

It was all too short a rest and refit in the autumn sunshine. John, who was now acting C.R.A.S.C. of the seaborne tail (Colonel Packe being in England with Jack Cranmer-Byng, Paddy Kavanagh and the rest of the airborne element), was often summoned to conferences in Brussels. Returning one afternoon he sent for me.

‘Dick, three of your glider-borne jeep sections are to go back to England today, as soon as they can be got ready. Will you see to it now, please?’

‘Am I to go too, sir?’

‘No.’

‘Does it matter which sections go?’

‘You can decide that yourself.’

‘Is it for -’

John looked at his watch, looked away and then at the papers in his hand. I saluted and set off for C Platoon lines.

There was no section of the seven in the platoon with which one would seize the opportunity to part. Sergeant Smith, Sergeant Potter and I decided to put seven bits of paper into a beret and draw three out. The three names which came out were Corporal Bater, Corporal Pickering and Corporal Hollis. Level-headed and cool, they got their men together and were off within the hour. I was not to see them again until well after the end of the war.

A few days later we found ourselves once more on the road, in and out of the company of Guards Armoured Division, each of whose vehicles bore their cognizance of an open eye. We were getting to know the sight of that eye. Slowly, we moved about forty miles north-eastward, towards the border with Holland. Around and ahead of us were heavy concentrations of troops and armour - that much we could tell. Most of us passed that night dozing in our jeeps, though some were lucky enough to be invited, subject to instant call by their mates, into their homes by the friendly Dutch. We were in Limburg, a little south of what was then called the Escaut Canal, but which I see is now called (in The Times Atlas) the Kempisch Canal, and about thirty miles south of Eindhoven in Holland.

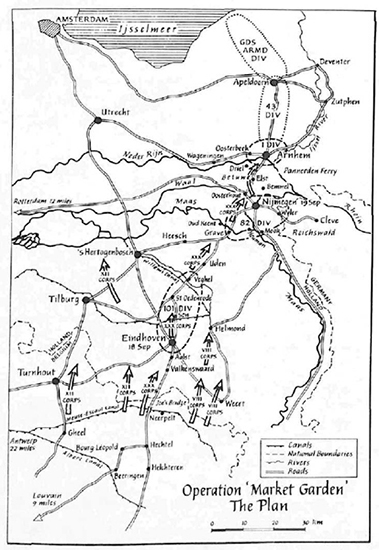

The following morning, 17 September 1944, John Gifford told his officers what was going to happen. We were on the threshold of a major operation code-named Market Garden. ‘Market’ was the airborne part and ‘Garden’ was the land offensive. The intention was to get the Allied 2nd Army, in one blow, across the Rhine and into northern Holland. This was expected to finish the war before the end of the year. The operation would begin early that same afternoon, soon after one o’clock (1300 hours), when the first lift of parachute and glider-borne troops would arrive from England.

The airborne army, three divisions strong, was due to land in relays during the next forty-eight hours, at different places along the fifty-odd miles between Eindhoven in Brabant and Arnhem in Gelderland. Not far east of its great delta at Dordrecht and Rotterdam, the Rhine divides into two arms - the Waal and the Neder Rijn - each a formidable river in itself. Only a few miles south of the Waal runs the river Maas. The 101st American Airborne Division were going to seize Eindhoven and the road leading northward to Grave. Meanwhile, 82nd American Airborne Division would capture the bridge over the Maas at Grave, and also Nijmegen, with its great bridge (the biggest road bridge in Europe) over the Waal. The star role, however, had been given to 1st British Airborne, who would in a few hours be in possession of the bridge over the Neder Rijn at Arnhem.

2nd Army, of which we were a very humble part - non-combatant, really — would attack that same afternoon, to synchronize with the airborne landings. They would advance on the axis of the Valkenswaard-Eindhoven road, linking up with 101st American Airborne. From there they would go on northward to Grave, cross the Maas bridge held by 82nd American Airborne, reach Nijmegen, cross the Waal and by Tuesday evening 19 September, be at Arnhem. There, then, our lot would meet up with Paddy, Jack Cranmer-Byng and also, no doubt, Corporals Bater, Pickering and Hollis. John said that the planned final objective of the whole operation, once 1st Airborne and the land forces had linked up at Arnhem, was Apeldoorn, about fifteen miles north. After that, the High Command (S.H.A.E.F.) would assess the situation and (as Captain Stanhope in Journey’s End says to his sergeant-major) advance and win the war.

This was heady stuff. This was what airborne soldiering was all about; a swift, dramatic blow to finish the enemy for good and all. The Allies had total air supremacy - not a Jerry ‘plane in the sky. The Germans had already been smashed to pieces in Normandy and had retreated to Holland without offering further resistance. Their morale was plainly shattered. 1st Airborne was now to play a major part in the Allies’ triumph: it would be a gâteau promenade of appropriate distinction.

I passed this information on to the four-sevenths of my platoon who were still around. I have never known morale higher. The men were excited and eager to go. About mid-day the company had a hot dinner and then waited about in the fine, slightly hazy autumn weather.

Our gliders and parachute aircraft (though we hadn’t actually been told this at the time) were to fly into Holland along two separate routes from south-east England. The northern route lay over Walcheren and thence a little south of ’s Hertogenbosch, where they were to diverge to the various dropping zones and landing zones of 1st Airborne and 82nd American. The southern route, 101st American Division’s, lay over Ostend and Ghent and then, a little east of Louvain, turned northward for their dropping and landing zones between Eindhoven and Veghel.

It was the fly-in along this latter route that we watched. About one o’clock the ‘planes and gliders came in sight and passed right over us. I don’t know the official numbers, but I would guess that we must have seen about a hundred bombers towing Horsa gliders and perhaps five hundred parachute aircraft. No such sight had ever been seen before and probably never will be again. The noise of the engines filled the sky, drowning all other sounds. The ground seemed stilled and the sky moving. The continuous streams of aircraft stretched out of sight, appearing, approaching and passing on overhead. They were quite low and from time to time we could plainly see people at the open doors and wave to them. I didn’t hear anyone in the Company utter any comment. We simply looked at each other with a wild surmise. Here, mighty beyond anything we could have imagined, was the war’s great climax. Even Driver Rowland, the platoon cynic, was plainly staggered. This lot was certainly not being done by Errol Flynn.

Now I know it tells in the books how General Horrocks, commanding XXX Corps, began his ground offensive as the first airborne troops landed that early afternoon, and how the Guards Armoured Division ran into tough opposition, but by nightfall had covered about nine miles towards Eindhoven. Horrocks has been criticized for not pressing on that night with fresh armoured troops, and for not putting in an infantry battalion to probe forward in the darkness and harass the Germans. I’m not competent to give an opinion. According to the plan as told to us, XXX Corps were supposed to reach Eindhoven that night, Nijmegen the following night and Arnhem on the next (Tuesday) afternoon. As everyone knows, this didn’t happen.

However, 250 Company knew nothing of all this, waiting in the fog of war to drive northward up the Eindhoven road. The weather grew worse and by the next morning - Monday morning - it was cloudy and raining; the notorious weather of Arnhem week, which was to be a major factor in preventing our Typhoons from giving 1st Airborne the vital support they needed.

It was Tuesday afternoon - a nasty, wet day - before we went into what had become known as ‘The Corridor’. We had seen great numbers of tanks and lorried infantry go past us, and no end of sappers with loads of bridging materials; and we had watched grubby bands of German prisoners being shepherded to the rear. More gliders and parachute aircraft - the second lift - had flown over us during the previous day. We had no least idea that anything might be wrong. Very likely, we supposed, XXX Corps were even now making whoopee at Arnhem with General Urquhart and the boys. All the time there was gunfire and throughout the nights there had been continuous noise and movement of vehicles. We were all sleepless. Still, that didn’t matter: now we were on the way.

I have only vague recollections of our journey up the Corridor to Nijmegen: about sixty to seventy miles. The extraordinary thing is that all the way we never saw a German and never came under fire. It was slow going, as usual. Along the road were signs, put up by the Sappers, warning against leaving the road, the verges not yet having been cleared of mines. We met with groups of American 101st, exhausted but glad to be alive. I recall a huge American signaller, using wire and pliers at the top of a tall telegraph pole and singing at the top of his voice ‘This is the G.I. jive - Man alive -’. In the little town of Veghel we waited a long time in the dark and the men quite rightly went to sleep. There were rumours of a German counter-attack and of The Corridor having been cut, but nothing happened. At length we were told to get moving again, and the whole place came to life with a great deal of noise - shouting and movement - in the midst of which an outraged voice yelled ‘Here, cut it out, all the damn’ row! We’ve got to stay here!’

I suppose it must have been very early on Wednesday morning that we crossed the Maas on the captured bridge at Grave. It was all high girders, and stuck between two ribs thereof was an unexploded shell. That shell looked distinctly wobbly. From Grave it was only about seven or eight miles to Nijmegen, where fighting was going on near the bridge and along the south bank of the 400-yard-wide river.

By this time we had all become more or less aware that the original scheme couldn’t have gone according to schedule; nevertheless, we were still in no doubt that we would soon get to Arnhem, where the 1st Division would be in possession of the bridge. 250 Company was ordered to camp in a field on the southern outskirts of Nijmegen, right next to two batteries of 25-pounder guns which were firing in support of the troops advancing northwards from Nijmegen. I’d never felt so tired or sleepless in my life. And still it rained and rained.

By that evening we knew — everyone in Nijmegen couldn’t but know - that things had gone badly wrong. The plain truth was that it was proving a hard and dreadful business to get over the Nijmegen bridge, to cross the Waal and establish a bridgehead on the northern bank. On either side of and below the embankment carrying the road northward to Arnhem lay the Betuwe polder - low-lying, marshy land, partly flooded. It was impracticable for tanks. German artillery was firing on Nijmegen. German infantry were resisting the Allied efforts to cross the bridge.

Why hadn’t the Germans blown the bridges at Arnhem and Nijmegen, reader, you may well ask? The answer is that Generalfeldmarschall Model had said not. He took the view that the bridges could be successfully defended against the Allied advance, and that they would then be needed for a German counter-attack. Other German generals had doubts about this, but Model’s view prevailed.

By the Wednesday afternoon, soon after we had arrived in Nijmegen, the Grenadier Guards and the American 82nd had fought their way to the southern end of the huge bridge, below which the river was running (as Geoffrey Powell tells in The Devil’s Birthday) at eight knots. The Americans, whose skill and courage throughout this dreadful week were beyond all praise, then crossed about a mile below the bridge in light assault craft. In the face of heavy German fire, only about half of them got across. Many were hit; many drowned. Yet those who got over routed the Germans on the other side, while meantime our troops had driven the enemy out of Nijmegen altogether - back over the bridge.

Four Guards Armoured tanks followed across and still the bridge wasn’t blown. Two of those tanks were hit, but the other two demolished the German anti-tank guns. By nightfall the Guards and the Yanks had joined up at a village called Lent, just north of the bridge, and the bridge and the Waal crossing were safely in Allied hands.

That night, we in 250 Company were all waiting for the order to join the advance to Arnhem and the bridge. As we waited, John Gifford characteristically sat his officers down to a four of bridge. I’m afraid I didn’t play very well. ‘But, Dick, we could have made four spades.’ (Bang!) ‘Sorry, sir.’ (Bang!)

The order never came. It wasn’t until about eleven o’clock on Thursday morning that Guards Armoured got orders to press on up the Arnhem road. During the night the Germans had rallied: they were now ready and waiting. The tanks, of course, couldn’t get off the road. As Geoffrey Powell says, they were like shooting-range targets at a fairground. The three leading tanks were knocked out and our infantry, doing everything they could to attack across the wet, flat polder on either side, had a very bad time. In brief, there was no getting on to Arnhem that day.

Meanwhile, what had been happening to Paddy Kavanagh and Sergeant McDowell, to Jack Cranmer-Byng, to Captain Gell (commanding our third parachute platoon), and to my three sections of glider-borne jeeps? By Friday we at least knew how desperate the general situation was, for on the Thursday night two senior officers of 1st Airborne, Lt.-Col. MacKenzie and Lt.-Col. Myers, acting on General Urquhart’s orders, had escaped from north of the Neder Rijn and reported to the headquarters of XXX Corps details of what was happening at Oosterbeek.

Today everybody knows, of course, the essential story: how the division’s first lift dropped on that fine Sunday afternoon, 17 September, and set off the eight miles eastward for the bridge: how Colonel John Frost, with a good proportion of 2nd Parachute Battalion, reached it, together with Major Freddie Gough, commanding the Reconnaissance Squadron. With them were a few divisional troops; some Sappers, some Gunners and our Captain Gell’s parachute platoon. David Clark was there, too. The rest of the division were prevented by the Germans from getting into Arnhem, and after very heavy losses on the afternoon of Tuesday, 19 September, were forced into a defensive perimeter, about a mile in diameter, most vulnerably based on Divisional Headquarters in the Hartenstein hotel at Oosterbeek, about a mile or so west of Arnhem. The southern end of the perimeter rested on the north bank of the Neder Rijn, and here there was a ferry of sorts. This was why it was considered worth hanging on. As explained, by Wednesday evening the Nijmegen crossing was in Allied hands, and it was still expected that the 2nd Army would reach the south bank of the Neder Rijn in force, take the ferry and relieve 1st Airborne.

During the week the eastern and western sides of the Oosterbeek perimeter were gradually squeezed closer together. By Sunday 24 September, they were only about half a mile apart, and full of holes at that. The Germans were prevented from cutting off the division’s precarious hold on some 600 yards of the north bank, to the east by a scratch force under the famous Major Dickie Lonsdale, one of the heroes of Arnhem, and to the west by what was left of the Border Regiment, who suffered badly.

By Thursday morning, 21 September, all resistance at the bridge had ceased. The remnants of 2nd Para., Colonel Frost (badly wounded), Freddie Gough, David Clark, Captain Gell and what was left of his platoon were prisoners in German hands. I want to emphasize that the whole division was only meant to hold the bridge for forty-eight hours. Colonel Frost and his men had held it for about eighty hours, against much heavier German opposition than had been expected, and if XXX Corps had come they could have had the crossing.

Of some 10,000 men of 1st Airborne who landed north of the Neder Rijn at Arnhem, about 1,400 were killed and over 6,000 - about one-third of them wounded - were taken prisoner. By Thursday morning, 3,000 sleepless, starving men were holding the Oosterbeek perimeter. 4th Parachute Brigade had virtually ceased to exist. (In the event, it did cease to exist: the survivors were transferred to 1st Para. Brigade and 4th was never re-formed.)

Corporals Bauer, Pickering and Hollis, their blokes and their jeeps all fell into the hands of the Germans. One soldier, a nice chap called Driver Eggleton, a Newbury man, escaped with the help of the Dutch Resistance after the glider he was in had force-landed in Holland short of the true landing zone.

Jack Cranmer-Byng (hit in the hand) and his platoon were among those shut into the Oosterbeek box. So were Paddy Kavanagh and Sergeant McDowell. I will now relate what happened to Paddy.

During the week, despite the adverse weather, ‘planes were flown from England to drop supplies to 1st Airborne. They had a bad time from German flak and many were lost. There was no ground-to-air communication (a bad fault, surely?) On account of this and also because the situation on the ground was so confused and in the rain visibility was so bad, most of the panniers fell outside the Oosterbeek perimeter. Colonel Packe asked Paddy to take his platoon and try to collect what he could of the nearer ones.

Paddy and Sergeant McDowell, their blokes and their jeeps set out from the 1st Airborne lines and drove down a narrow, empty lane bordered by fairly thick woodland. As they were coming over a little hump-backed bridge they were caught in German small-arms fire. Corporal Wiggins and several more died instantly. Several jeeps were smashed up.

Paddy grabbed a Bren gun and leapt into the ditch beside the verge, whence he returned the German fire. Sergeant McDowell joined him.

‘Take the blokes, sergeant!’ yelled Paddy. ‘Get them out of here - back through the woods. I’ll cover you.’

‘You sure of that, sir?’ asked McDowell.

‘Yes,’ answered Paddy. ‘Get out! That’s an order!’

Somehow or other Sergeant McDowell got most of the platoon together inside the edge of the wood. Three or four lay writhing and screaming on the road. There was blood everywhere. Paddy, who had several magazines, continued firing. The platoon retreated on foot. After a minute or two they stopped to listen. Sergeant McDowell told me how you could hear the rrrrip, rrrrip of the German Schmeissers against the slower rat-tat-tat of the Bren - a dreadful counterpoint. Suddenly there was an explosion, and then nothing more.

Paddy lies among the others in the divisional cemetery at Oosterbeek.

Let other pens dwell on guilt and misery; the misery of that weekend at Nijmegen, anyway. Until the very end we continued to believe - not just to hope, but to feel sure - that we would get to the Neder Rijn and reach the division at Oosterbeek. On Thursday evening the Polish Independent Parachute Brigade dropped on the south bank of the Neder Rijn at Driel, more or less opposite the 1st Airborne perimeter, and were joined next day by some of the Household Cavalry from Nijmegen. Only a few of the Poles, however, managed to get across the river in the mere couple of amphibious vehicles (DUKWs) available. The Somerset Light Infantry, the D.C.L.I. (Durhams) and the Worcestershire went forward from Nijmegen. Heavy fighting in the Betuwe - the low-lying area between Nijmegen and Arnhem - went on all Saturday and Sunday. The long and short of it was, however, that the Germans couldn’t be entirely driven away and no effective link could be established between 2nd Army at Nijmegen and 1st Airborne in the box.

Throughout all this the ‘seaborne tail’ of 250 Company had nothing to do but to wait, uselessly, at Nijmegen. We might as well not have been there. It was on Sunday evening, the 24th, that John Gifford said to me ‘Apparently, if it’s no better by tomorrow night they’re going to pull the division out, back over the river.’

‘Pull them out, sir? You mean, the whole thing’s off? We’re not going to Arnhem at all?’

‘Looks like it.’

And as everyone knows, that is what happened. Of the 10,000 men who had landed at Arnhem, about 2,160 got back during the Monday-Tuesday night, the 25-26 September. Among them was Jack Cranmer-Byng, with a handful of our lot, including Sergeant McDowell. Jack subsequently got the M.C.

It is interesting to record what was going to happen if they hadn’t. Generalfeldmarschall Model wasn’t going to send in his soldiers - even with armour - finally to reduce the starving Oosterbeek box. He knew what they could expect. 1st Airborne was going to be destroyed by heavy artillery at long range. Very brave and prudent, I’m sure.

At some time in the early evening of Tuesday, the 26th, I was sent down to the centre of Nijmegen to ask the Divisional Camp Commandant, Major Newton-Dunn (generally known in 1st Airborne as Hoo Flung Dung), about certain arrangements made for 250 Company. I asked him whether, as the survivors had come in during the night, he had happened to see Jack Cranmer-Byng. Hoo Flung replied that he hadn’t been able to notice any one particular person more than another. Then he said ‘And if you like I’ll show you why.’ He guided me a short distance to a huge building - I think it must have been a gymnasium - with a wooden floor and no tables, chairs or any other furniture in it at all. That’s all I can recall about it. It was all in twilight, so you couldn’t see much anyway. As we approached the open door, Hoo Flung laid a finger to his lips.

Inside, those who had got back from Oosterbeek were lying on the floor, huddled asleep under grey army blankets. The majority had not slept for a week. At Driel, during the previous night, they had been given a light, hot meal (they had been starving for about five days) and then, having got to Nijmegen, been put in the gym. to sleep.

On account of the dim light in the big building, visibility was limited. The grey rows of unconscious, motionless shapes stretched away until they blurred and you couldn’t make out the far end.

As well as Paddy, we had lost two other officers killed: Lt. Daniels, the big chap whose blokes C Platoon had succeeded at Edale: and Thompson, who had been subaltern in one of the other para. platoons.

Later, looking at the lists, I learned that people whom I had known well at Horris Hill and Bradfield were also among those killed: Roddy Gow; David Madden. Their names are on the appropriate war memorials.