No people in history were as obsessed with the power of the ring as the Vikings. The ring was wealth, honour, fame and destiny to these warrior people. Under its sign they charted unknown seas, waged barbarous wars, sacrificed man and beast, pledged their faith, made great gifts of it, and, finally, died for it. Their gods were ring lords of the heavens, and their kings were ring lords of the earth.

In the ring quest myths of the Vikings, that ferocious warrior culture of Norsemen, we see one of the primary sources of inspiration for Tolkien’s fantasy epic, The Lord of the Rings. Although the symbol of the ring was widespread and prominent in many far more ancient cultures, it was the Norsemen who brought the ring quest to its fullest expression, and to the very heart of their cultural identity. Virtually all subsequent ring quest tales in myth and fiction are deeply indebted to the Norse myths. The Lord of the Rings, although striking in its originality and innovation, is no exception.

Among the Vikings, the gold ring was a form of currency, a gift of honour, and sometimes an heirloom of heroes and kings. (Such a ring belongs to the Swedish royal house, the Swedish kings’ ring known as Svíagríss.) At other times, when great heroes or kings fell, and it was thought none other would be worthy of the honour of the ring lord, the ring-hoard (the treasury of a nation or people, often made up of rings of gold) was buried with its master.

So, in barrow and cave, in mere and grave, upon burial ship sunk beneath the sea, the rings slept with their ring lords. Afterward, tales were told of dead men’s curses and supernatural guardians. In Norse myth and in Tolkien’s tales, guardians of treasures and ring-hoards take many forms: damned spirits, serpents, dragons, giants, dwarfs, barrow-wights and demon monsters.

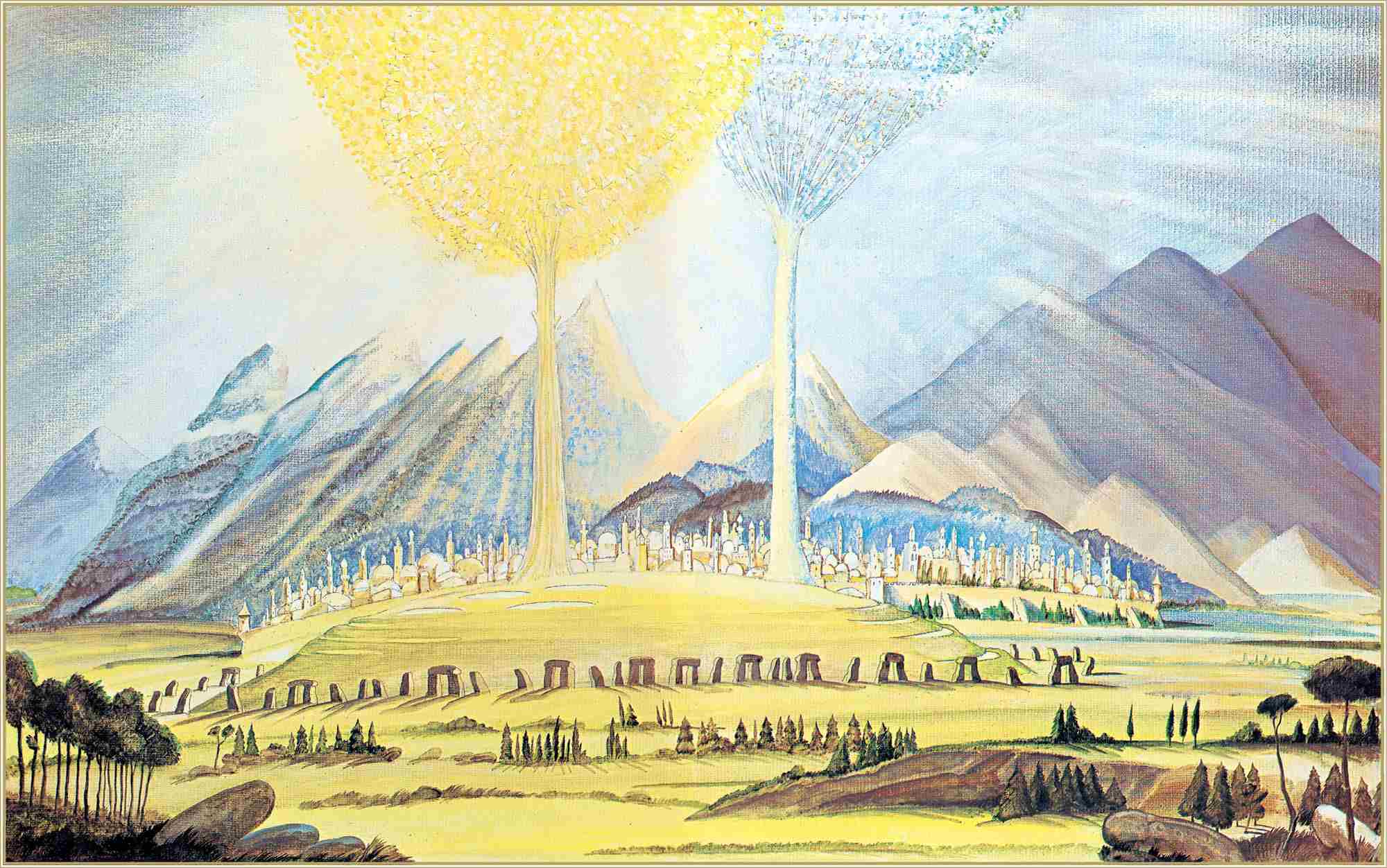

The rings of Norse mythology – like Tolkien’s – were commonly magical rings forged by elves. These gold rings were tokens of both power and eternal fame. They were also symbolic of the highest power: destiny, the cycle of doom. Indeed, the Domhring, the Ring of Doom – the ring of monolithic stones that stood before the Temple of Thor – was perhaps the most dreaded symbol of the violent law of the Vikings. (In Tolkien, an identically named “Ring of Doom” stands outside the gates of Valmar, the city of the Valar.) In the centre of this ring of stones was the thunder god’s pillar, the Thorstein. The histories tell us of its use. In the 9th century, the Irish king Maelgula Mac Dungail was made captive in the Viking enclave of Dublin. He was taken to the Ring of Doom and his back was broken upon the Thorstein. Of another such ring in Iceland, a scribe in the Christian 12th century wrote that bloodstains could still be seen upon the central stone.

Yet the great pillared temple of the fierce, red-bearded thunder god housed another very different – but to Norse society infinitely more important – ring. Thor’s weapon was the hammer called Mjölnir, “Destroyer”, but Thor’s most valued gift to humankind was the altar ring that was housed in his temple. This was the Oath Ring of Thor, the emblem of good faith and fair dealing.

On the sacred altar was a silver bowl, an anointing twig, and the Oath Ring itself. Whether of gold or silver, it had to weigh more than 20 ounces. Thor’s statue, mounted in his goat-drawn chariot, dominated the sanctuary while around the altar were grouped the 12 figures of his fellow gods, their eyes fixed upon the ring.

When an oath was to be taken, an ox was brought in and slaughtered, and the hlaut, the sacred blood, was sprinkled on the ring. Then the man laid his hand upon the ring and, with Thor gazing down on him, faced the people and said aloud: “I am swearing an oath upon the Ring, a sacred oath; so help me Freyr, and Njörthr and Thor the Almighty…”

For the Vikings, such an oath was legally binding, and when the world’s first democratic parliament, the Althing, was established in Iceland in 930, the temple priests brought out the Oath Rings to reinforce its law.

Yet Thor was not the only ring lord among the gods, nor was the power of his ring supreme. The greatest power was in the ring on the hand of Odin, the magician and king of the gods. Odin was the Allfather, Lord of Victories, Wisdom, Poetry, Love and Sorcery. He was Master of the Nine Worlds of the Norse universe, and through the magical power of his ring he was, quite literally, “The Lord of the Rings”.

But Odin was not always almighty, and his quests for power and for his magical ring were long and achieved at great cost. He travelled throughout the Nine Worlds on his quests and hid himself in many forms, but most often he appeared as an old man: a bearded wanderer with one eye. He wore a grey or blue cloak and a traveller’s broad-brimmed slouch hat. He carried only a staff and was the model for the wandering wizard and magicians from Merlin to Gandalf.

Before delving more fully into the myth of Odin’s ring, it is important to first take a look at an overview of Tolkien’s cosmology and compare it to that of Norse mythology. Although Tolkien’s world is profoundly different in many of its basic moral and philosophical perspectives from that of Viking mythology, similarities are numerous and significant.

The most immediate parallel for anyone even mildly familiar with Norse myth is that the world of mortal men in both Norse myth and Tolkien’s world have the same name: the Norse “Midgard” literally translates to “Middle-earth”.

The immortal gods of the Norsemen are made up of two races: the Æsir and the Vanir, while Tolkien’s “gods” (we should properly call them entities or spirits) are originally called the Ainur, but become known as the Valar in their earthly form. In both systems, the gods live in great halls or palaces in a world apart from mortal lands. The Æsir live in Asgard, which can be reached only by crossing the Rainbow Bridge on the flying horses of the Valkyries. Tolkien’s Valar live in Aman, which, after the reshaping of Arda at the end of the Second Age, can be reached only by crossing the “Straight Road” in the flying ships of the Elves.

Mahanaxar the “Ring of Doom” – the sacred circle of standing stones before the gates of Valmar, the city of the Valarian “gods” of Arda

Norse cosmology was rather more complex than Tolkien’s in its elemental structure. Asgard and Midgard were just two of its nine “worlds”. However, Tolkien’s “worlds” are far more cosmopolitan and most of the inhabitants of the nine Norse worlds are recognizable within his two.

Besides the worlds of Midgard and Asgard, Norse myths tell of the worlds called Alfheim and Swartalfheim: the realms of the light elves and the dark elves. These were parallel to Tolkien’s Elves, who are divided into two great races: the Eldar, who are (for the most part) Light Elves, and the Avari, who are Dark Elves.

The dwarfs of Viking mythology were also given their own world. This was a dark underground world of caves and caverns called Nidavellir, which was found beneath Midgard, where the dwarfs constantly worked their mines. These dwarfs share many of the characteristics of Tolkien’s Dwarves, although in Tolkien both Dwarves and Elves are more highly defined and individual, and their genealogies are far more complex.

It is notable that Tolkien took the names of most of his Dwarves directly from the text of Iceland’s 12th-century Prose Edda. The Edda gives an account of the creation of the dwarfs, then lists their names. All the Dwarves in The Hobbit appear on this list: Thorin, Dwalin, Balin, Kíli, Fíli, Bifur, Bofur, Bombur, Dori, Nori, Ori, Óin and Glóin. Other names of Dwarfs which Tolkien found in the Prose Edda included Thráin, Thror, Dáin and Náin. The Edda also gives the name Durin to a mysterious creator of the dwarfs, which Tolkien uses for his first Dwarf king of “Durin’s Line”. Rather surprisingly, another of the Icelandic dwarfs is named Gandalf. Undoubtedly, however, it was the literal meaning of Gandalf – “sorcerer elf” – that appealed to Tolkien when choosing this name for his Wizard.