The swan ships of the Elves sailing from the world of mortal Men over the “Straight Road” to Eldamar

The swan ships of the Elves sailing from the world of mortal Men over the “Straight Road” to Eldamar

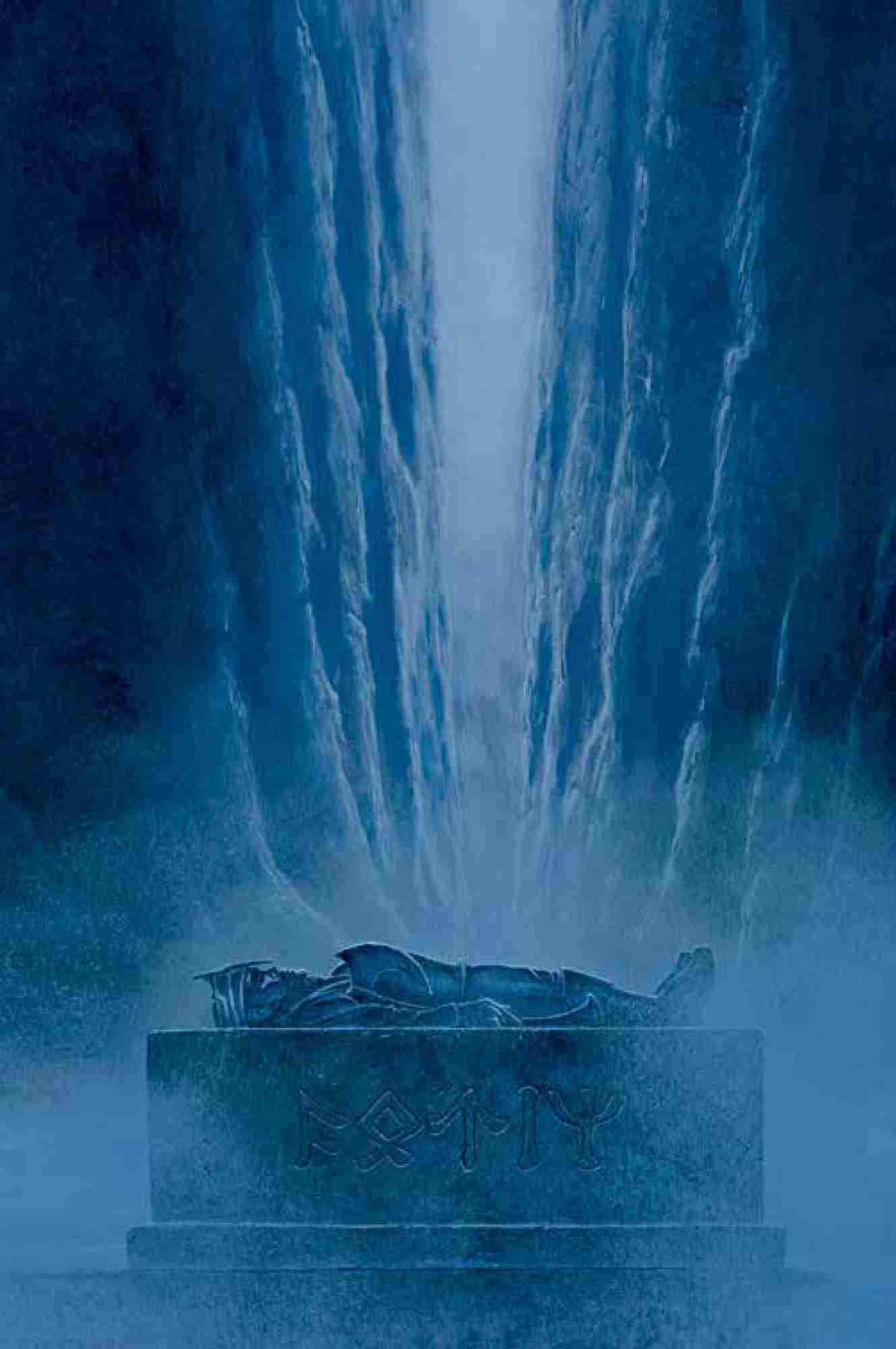

First of the Seven Fathers of the Dwarves – King Durin the Deathless

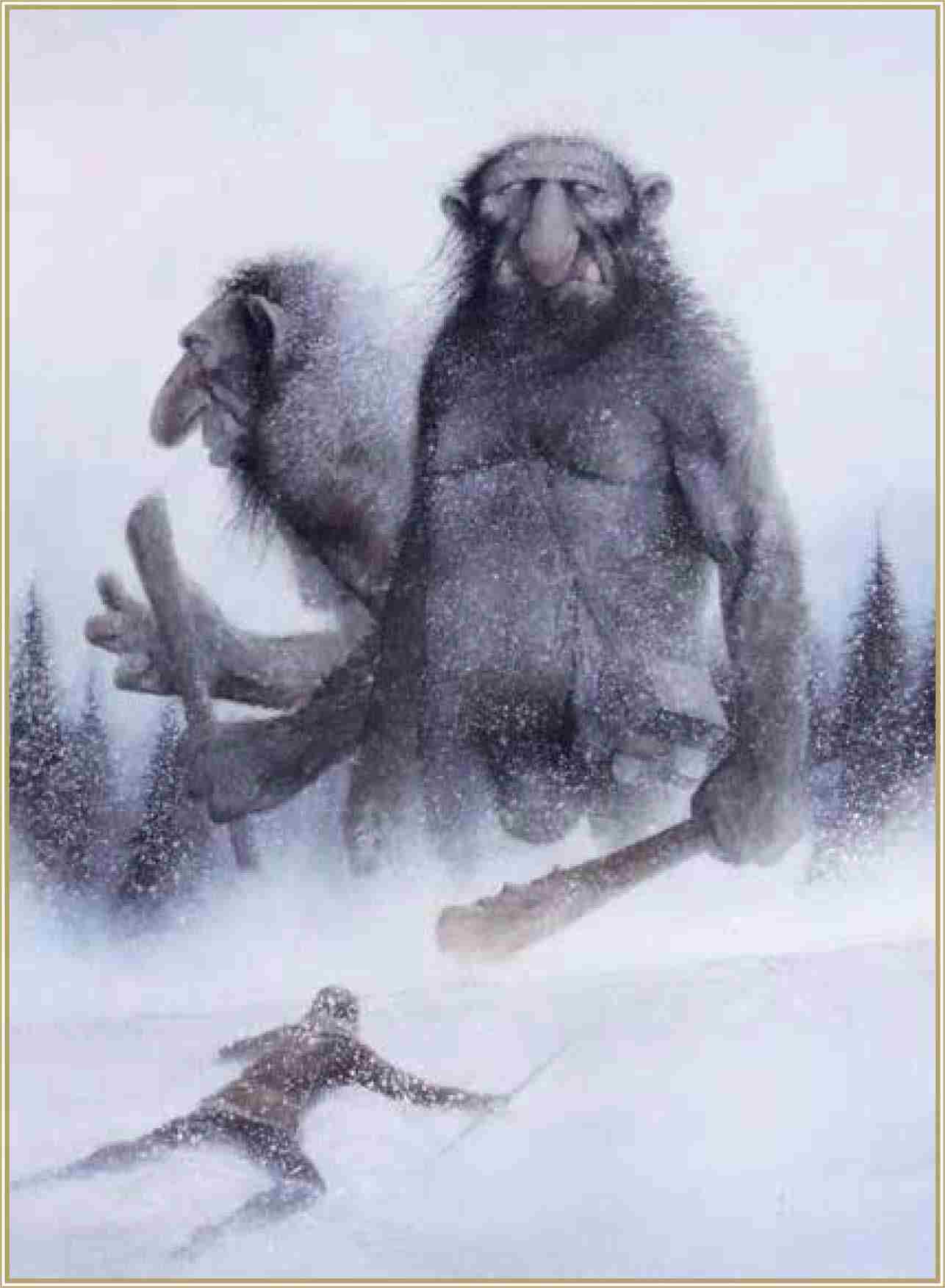

The Norsemen gave two worlds to their races of giants: Jötunheim and Muspelheim. Jötunheim was the home of the cave-dwelling rock and frost giants. In them we see the recognizable characteristics of the large, stupid and easily outwitted monsters that evolved into the trolls of Scandinavian fairy tales. In Tolkien, these became his similarly stupid Stone Trolls and Snow Trolls.

In the world of Muspelheim, however, we find the far more formidable fire giants. Undoubtedly fire giants are personifications of volcanic subterranean powers. For once released from Muspelheim, fire giants were virtually unstoppable. In Ragnarök, the final battle of gods and giants at the end of time, they played a major part in the destruction of the world. In Tolkien, we see something of these terrible titans in his creation of the Balrogs, the fiery “demons of might”.

Another world was Vanaheim, the home of the second race of gods, the Vanir, a race of nature spirits of the earth and air who are also magicians capable of casting terrifying spells. In Norse myth these magician gods are not clearly defined as the dominant Æsir gods, but they seem to resemble Tolkien’s Valar in their early manifestations as elemental spirits or “forces of nature”.

The deepest world of all was Niflheim, the dark and misty land of the dead. In this cold and poisoned land was the great walled citadel of Hel, the goddess of the dead. The gate of the fortress of Hel was guarded by Garm the Hound, and within were imprisoned the damned spirits of the dead. This is comparable in Tolkien’s Silmarillion to the cold and poisoned land of Angband (“iron fortress”), which is ruled by Morgoth, the spirit of darkness. The gate of the fortress of Angband was guarded by Carcharoth the Wolf, and within were imprisoned many Elves who were hideously tortured and transformed into a race of damned beings called Orcs. By the time of the War of the Ring, Morgoth’s disciple Sauron attempts to recreate Angband in his dark and evil land of Mordor.

Ultimately, Norse myth and Tolkien’s fiction both had cosmologies that share a stoic fatalism in their ultimate destiny. In Viking myth, the spirits of slain warriors are gathered in the Hall of Valhalla in Asgard, while, in Tolkien’s tales, the spirits of slain Elves inhabit the Halls of Mandos in Aman. Both remain there and await the time when they are called to participate in the cataclysms that will end their worlds. This is the great conflict of elemental forces that the Vikings called Ragnarök and Tolkien called the World’s End.

Tolkien’s vision of his World’s End is deliberately veiled, but we see some comparisons between the Viking Ragnarök – when the rebel god Loki led the giants into battle against the gods – and Tolkien’s cataclysmic Great Battle in The Silmarillion. When Eönwë, the Herald of the Valar, blows his trumpet, the Valar go into battle against the rebel Vala Morgoth and his monstrous servants at the end of the First Age of Sun. The Viking Ragnarök was a battle between the gods and the Giants, which similarly commenced when Heimdall, the Herald of the Gods, blew his horn. Ragnarök ended with the destruction of all the Nine Worlds. Tolkien’s Great Battle results in the total destruction of Morgoth and his evil kingdom of Angband, but it also tragically causes the beautiful Elvish realms of Beleriand to sink beneath the sea.

Norse Gods in contention with the Giants and monstrous elemental forces for domination over the Nine Worlds

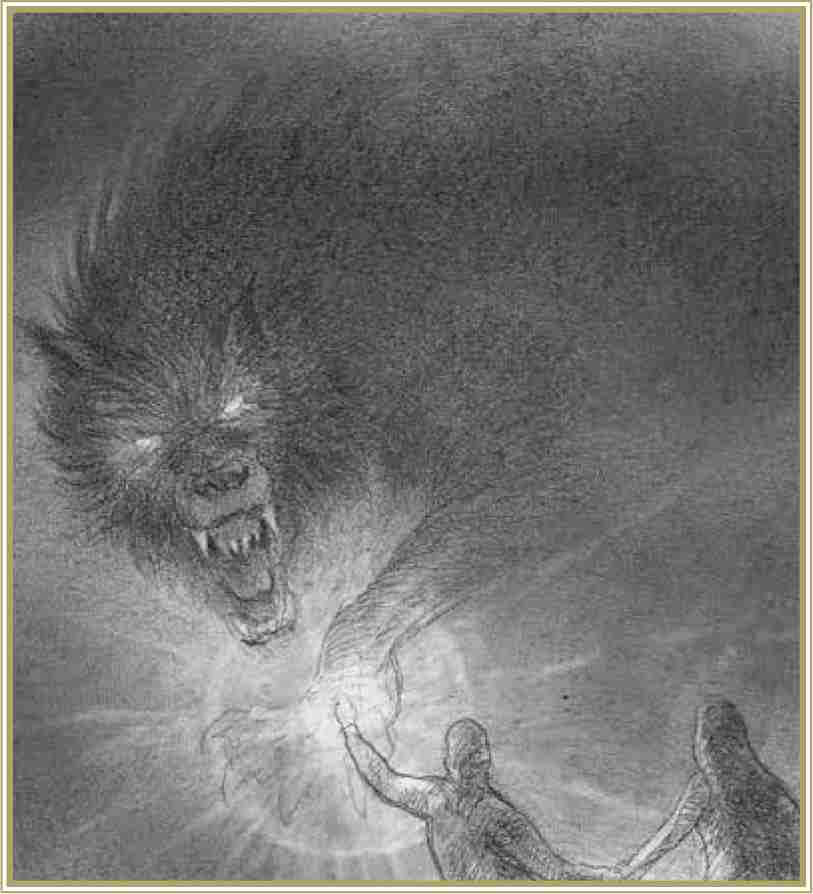

Battle of the great wolf Carcharoth and Beren Erchamion at the Gates of Angband

Some tales in Tolkien’s writing directly echo episodes in that cataclysm of Ragnarök. In the Quest of the Silmaril, the hero Beren attempts to use the fiery Silmaril to drive back Carcharoth, the Giant Wolf of Angband. However, the beast bites off Beren’s hand at the wrist and swallows both hand and the flaming jewel. Carcharoth, the Red Maw, is filled with horrific pain as the jewel sears his accursed flesh and consumes his evil soul from within. The great beast is like a raging meteor loose in the land, full of pain and wrathful power until at last he is slain.

In Tolkien’s tale, Carcharoth is comparable to the Norse myth of Fenrir, the Giant Wolf who bit off the hand of Tyr, the heroic son of Odin. Fenrir was the monstrous offspring of the evil rebel god Loki and, like Carcharoth, was the largest and most powerful wolf in the spheres of the world. During Ragnarök, Fenrir devoured the sun, which burned and consumed him from within but filled him with wrathful power until at last he was slain.

In The Lord of the Rings, Gandalf’s battle with the Balrog of Moria mirrors another duel in Ragnarök. In the giant Balrog of Moria, who fights the Wizard Gandalf with a sword of flame on the stone bridge of Khazad-dûm, we have a diminished version of Surt, the fire giant, who fights the god Freyr with a sword of flame on the Rainbow Bridge of Bifrost. Both duels end in disaster when the bridges collapse beneath them, and both the combatants hurtle down in a rage of flame.

Although both Tolkien and the Norsemen share a cataclysmic vision of the end of their cosmologies, this vision is not without hope. Out of these conflicts, both promise that this ending is also a transition: a newer, better and more peaceful world is to be reborn from the violent old one.

Tolkien’s inspiration is drawn from a far wider range of sources than this brief comparison of cosmologies suggests. However, the influence of Norse myth in the shaping of Tolkien’s world is undeniable. This becomes even more evident when we examine ring myths of that civilization, and especially those myths that relate to the king of the Viking gods, Odin.