CHAPTER

6

The news that Uncle Solomon had for Freddy was indeed important. Mr. Bean had been arrested. Mr. Herbert Garble’s sister, Mrs. Underdunk, with whom he lived, had found a handkerchief marked W.F.B. in front of her bureau that morning, and on looking through the bureau drawers, claimed to have missed several valuable rings. She had at once called the sheriff, who had had no choice but to go out and arrest Mr. Bean and take him down to the jail.

“Why, that’s outrageous!” said Freddy. “And I suppose the handkerchief was clean and unironed.”

The screech owl said it was.

“H’m,” said Freddy thoughtfully. “There were four handkerchiefs stolen from the Beans’ clothesline, I think.”

“That means that whoever stole them will probably burglarize two more houses, leaving a handkerchief in each one,” said Mr. Camphor.

“Not while Mr. Bean’s in jail, if they have any sense,” Freddy said.

“Correct,” said Uncle Solomon in his precise little voice. “That would merely be confirmation of your theory of Mr. Bean’s innocence. For while in jail, Mr. Bean could certainly not be engaged in burgling, and so could not have left the third handkerchief. And if he could not have left the third handkerchief, one could assume it much less likely that he had left the first and second.”

“I don’t need ’em to leave any more handkerchiefs around to prove that Mr. Bean isn’t a burglar,” Freddy said a little crossly.

“To prove it, that’s just what you do need,” said the owl. “I think it is unlikely that Mr. Bean stole anything. But that is an opinion; it is not knowledge. Knowledge is something you know, and I do not know that he is innocent.”

“Well, I do,” Freddy said. “For that matter, I don’t know that you’re innocent either, Uncle Solomon. Maybe you stole the things. You could get in a window and steal something and leave a handkerchief.”

But if Freddy hoped to make the owl mad, he failed. “Dear me,” said Uncle Solomon, giving a cold little tittering laugh; “now you’re beginning to think. And if you’ll only think a little more along that line, you’ll think of a way to get Mr. Bean out of jail.”

“Golly,” Freddy exclaimed after a minute. “I know what you mean. But I can’t climb up into any window. Look, if I get the handkerchief for you, will you do it?”

Freddy expected that the owl would refuse, and probably laugh at him for suggesting such a dangerous mission. But for once, Uncle Solomon was serious. “You get the handkerchief,” he said. “I’ll do it tonight. I like your Mr. Bean,” he continued. “And though you probably don’t realize it, he’s in a very dangerous situation.”

“This handkerchief trick will get him out of it,” said Freddy.

“Oh, I don’t mean his being in jail. Matter of fact, he’s probably safer there than he would be back in his own home.”

“Good gracious,” said Mr. Camphor, “you mean this revolt among the animals that Freddy has told me about? But it’s silly of them to think they can take over and run things. It’s—”

“Listen,” the owl interrupted. “I know more about this than you suspect. I’ve heard a great deal, and I’ve put two and two together, and I do not like the answer. These talks that someone is giving up at the Grimby house—they are only part of it. They are being given for the purpose of turning farm animals against the men who own the land they live on. So that on the day when the revolution begins, there won’t be much local resistance.

“But the leader of this revolution knows quite well that farm animals alone cannot seize the power. Up in the woods, across Otesaraga Lake, in the foothills of the Adirondacks, he is training an army—an army of wild animals who are no friends to humans. Animals that humans have hunted and trapped. And with them are a good many discontented farm animals. Mr. Witherspoon’s horse, Jerry, is one of them. You’ve probably heard that he’s been missing for a month. He got sick of not having enough to eat at Witherspoon’s and he joined the revolutionists. And some of your Bean farm rabbits are there too.

“When the signal is given, they’ll come down and drive the farmers from their farms. They’re going to start right in this neighborhood around Centerboro. As soon as the farmers are driven off, they’ll turn over the management of the farm to those of the farm animals who have joined up with their organization, and they’ll go on to the next farm. They believe in a year, they’ll have the whole state under animal control.”

“My goodness,” said Mr. Camphor, “that would let me out of being governor, wouldn’t it?”

“It would also let you out of living on this nice estate,” said the owl. “Unless you get busy, a year from now, perhaps two months, there’ll be cows and horses and porcupines sitting in the comfortable chairs out there on your terrace, instead of politicians.”

“Much rather have them there, too,” Mr. Camphor muttered.

“But Uncle Solomon,” said Freddy, “do you really think they can get away with it? Do you believe that Mr. Bean’s animals will turn against him and drive him out of his home?”

“Your Mr. Bean is a special case, I admit,” said the owl. “He’s been nicer to his animals, and more thoughtful for their comforts, than most farmers. I think they may put up a fight for him. But suppose now that you’re a pig on any of these other farms around here. You live in a dirty pig pen, and the farmer feeds you plenty, but what kind of food is it? The least you can say is that it’s pretty coarse stuff, and not very daintily served either. And then somebody comes along and says: ‘How’d you like to change places with this farmer, and have him live in the pen and eat out of a trough, and you sit down at the table with a nice white tablecloth with only a few spots on it, and sleep between nice clean sheets—’ Well, what are you going to say to that?”

“I guess you’re going to say: ‘I’m for it,’” Freddy replied.

“Goodness’ sake,” said Mr. Camphor, “it looks as if the animals were going to get the vote whether I run for governor or not.”

“Those who think they’re going to have a vote under an animal dictator are very much mistaken,” said Uncle Solomon. “The country will be run the way Russia is; every animal will be told what to do, and if he knows what is good for him he’ll do it. Animals that try to remain loyal to their human masters will be moved out and replaced by rough characters from the Adirondacks.”

Freddy said: “Jimson, I think I ought to go back to the farm and have a talk with Mrs. Wiggins and Jinx, and with Mrs. Bean, too. If you’ll come with me, Uncle Solomon, we’ll get that handkerchief and plan where to use it.” He turned to Mr. Camphor and said: “I’m afraid I haven’t been much help, but I’ll come back later if you want me to. Maybe I can think of something.”

“I’ll drive you down,” said Mr. Camphor. “And don’t worry about me. After all, a governor only serves two years.”

“But maybe they’ll re-elect you for another term.”

“You leave that to me,” said Mr. Camphor with a grin.

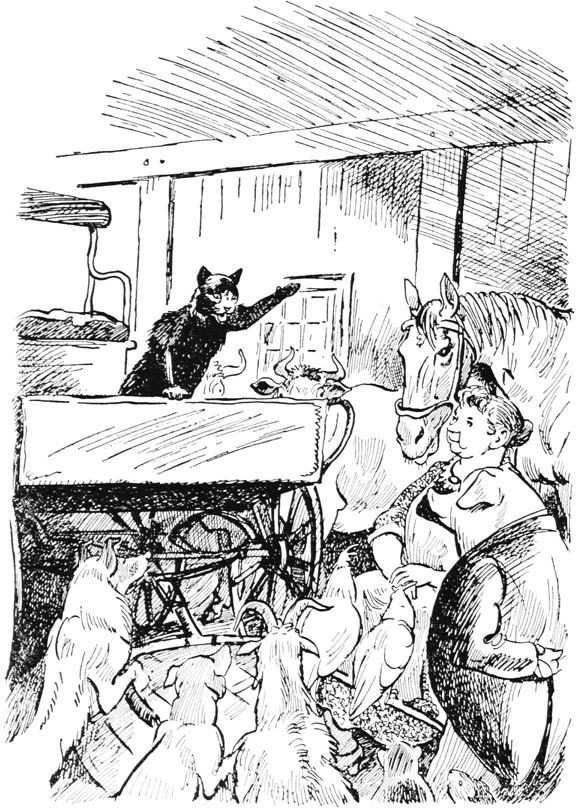

Freddy got an unironed handkerchief marked W.F.B. from Mrs. Bean and gave it to Uncle Solomon. He and Mr. Camphor had a long talk with Mrs. Bean, and later in the afternoon he quietly notified all the animals whose loyalty he was sure of, and held a meeting in the cowbarn that evening. For the first time, Mrs. Bean was present at one of these meetings. While Freddy told of the danger that hung over the farm, and while they discussed plans for fighting off the revolutionists, she didn’t say anything; but when at the end, all the animals filed past and pledged loyalty to the Bean farm, and swore to fight to the death to defend it, she cried. None of the animals had ever seen her cry before, and they were very much affected. Even Jinx, who was a pretty hard-boiled cat, was so deeply moved that for the first time in his life he made a speech.

When they had all sworn, he leaped up onto the dashboard of the old phaeton, from which the other animals who had addressed the meeting had spoken, and said: “You animals, tonight you’ve heard a lot of plans discussed. I’ve got nothing against that. You’ve heard a lot of patriotic talk. I’ve got nothing against that either. But talk is easy; talk alone ain’t worth five cents a scuttleful. What we want is action. Are we just going to sit here and let these folks take our homes away from us? Or are we going to go up and take their homes away from them? Oh sure, sure—we’re going to fight to the death to defend this farm. Well, why wait and let them bring the fight to us? Why not let them fight to the death to defend their own homes? How about it, boys; shall we sit here and wait for ’em, or who’ll follow me up to their next meeting at the Grimby house tomorrow night? We’ll clean up that gang, and then we’ll go on up around the lake into the Adirondacks and find the rest of ’em and drive ’em back where they came from. Eh? How about it? Who’s with me?”

“What we want is action!”

There was a roar of applause, and a number of the more hot-headed animals crowded up towards the cat. But Mrs. Bean got to her feet; and immediately the uproar subsided.

“Animals and friends,” she said, “I thank you from the bottom of my heart for this wonderful demonstration of loyalty. But I ask you to consider this: If you attempt to strike now, without organizing, without planning carefully, you may very well bring down on our heads just the fate that you are trying to escape. Before you do anything, get Mr. Bean’s advice. I’m sure he’ll be back home in a day or two, and then you can talk to him.”

“He’ll be home tomorrow,” said Freddy emphatically.

“I hope you’re right,” Mrs. Bean said. “Goodness, I just baked him an apple pie, and it makes me want to cry every time I look at it and think of him sitting down in that old jail, gnawing at a dry crust—”

“The sheriff sets a good table, ma’am,” said Freddy. “He’s probably gnawing at roast turkey and plum pudding. But I’ll take that pie down to him if you say so.”

“Why, thank you, Freddy. That would be real nice. But what I was saying,” she went on: “Talk to Mr. Bean before you do anything. If more people would talk to Mr. Bean before they do things, there’d be less trouble in the world.”