CHAPTER

14

To the consternation of Freddy and Jinx, the imprisonment of Simon and Mr. Garble had little effect on the course of the revolution, which spun along under its own steam. The newspapers published the story of Simon’s capture, but Ezra proclaimed himself dictator in his father’s place, and farm after farm continued to be taken over without resistance. The Governor had a regiment of soldiers sent into the area, but there wasn’t anybody to shoot at; only animals grazing quietly in the fields. The wolves faded off into the woods, and the other animals refrained from violent acts while the soldiers were in the vicinity. There was nothing for them to do.

The Camphor house was in a state of siege. The Indians stayed on and their guns kept the wolves at a distance, but such supplies as were needed had to be fetched from Centerboro under armed convoy. Fortunately, there was a large quantity of food stored in the house. The committee wanted to get back to their homes, but there was no way of taking them there. They had finally run out of funny stories, and this made them cross and snappish, as there was nothing else to talk about. Only Miss Anguish seemed to be enjoying herself; she read and crocheted, and spent a good deal of time talking with Simon, where he hung from the drawing-room chandelier. He tried every way he could think of to get round her and persuade her to set him free, but she always managed to refuse on some pretext or other.

Freddy and Jinx had not been mentioned in the newspaper stories of the capture of Simon, and they were consequently free to move about the country without being challenged. Ezra had made several speeches from the Grimby cellar hole, but he was a poor speaker and with no microphone to increase the sound of his voice, the enthusiasm of his followers had definitely fallen off. It was this that encouraged Jinx and Freddy to persuade Mr. Camphor to go down under armed guard one evening and make a speech giving the human point of view. Ezra was to speak that night, but the Indians and the Bean animals drove him and his guards away, and then Mr. Camphor stood at the top of the cellar steps and spoke.

“Fellow animals,” he said, “—for remember that, though a man, I too am an animal—I have come to speak to you tonight because there are two sides to every question, and so far, only one side has been presented to you. Simon has ably presented the side which believes that the animals should take over. I wish to present the side which believes that men should be left in charge.

“This does not mean that I believe animals should have no hand in running things. I will take that up a little later. For the moment, let us consider what will happen in a world run by Simon the Dictator.

“In the first place, paws and hoofs cannot be used in many operations which are necessary on a farm—in running machinery and so on. Men will have to be kept on to do all this work—which now they do willingly. But will they do it well or willingly if they are under the orders of a cat or a horse? Men will have to be slaves, and there will be hatred between men and animals, as always between masters and slaves. Will life be as pleasant for either men or animals under those circumstances?

“Again, Simon has told you that you will live in the houses and the men will occupy the barns. I don’t believe any horse or cow wants to live in a house, any more than any man wants to live in a barn. Every animal likes to live in the type of structure which is built for him. Men in houses, cows in barns, horses in stables.”

Mr. Camphor developed this idea at some length, as you can do for yourself if you have the patience. Then he went on to remark that Simon had much to say about slavery. But the relationship between men and animals was a partnership, he said, not slavery. Cows were free to wander about the pastures; they did no work. Horses worked, but their hours were not long; they were simply doing their share of the work that produced food for both them and the farmer. Dogs were sometimes tied up, but only when they were cross and might bite somebody.

The animals listened in silence. Now and then, there was a buzz of agreement. The audience seemed to be composed mostly of farm animals; no wolves were in evidence, and Jinx reported that he could find only a few of the gaunt hill cattle and horses from the north.

When he had spoken for some time, Mr. Camphor said: “Many of you, I suppose, support Simon because you feel that in our present form of government, animals have no vote. But if you believe that under a dictator you will have some say in the government, you are making a great mistake. There will be one party: Simon’s. If you vote at all, you will vote for Simon. There will be nobody else to vote for. You will have no freedom of choice and very little of action. You will be worse off than you are now.

“Apparently, you have the choice between being slaves to a rat, or what some call slaves to humans. This is a bad situation. But there is a cure for it. I can tell you what it is in three words: Votes for animals!”

There was some scattered applause at this, and Mr. Camphor went on to talk, as he had to the committee, about what he called “full representation.” He said nothing about being a candidate for governor, but stated that he intended to use his influence to have a bill presented in the next legislature admitting animals to the vote. And this, he asserted, would be far better than having the animals take over under a dictatorship. “Animals must govern with men,” he said. “It is no more fair for animals to have all the power than it is for men to have it.”

There was a good deal of applause at the end of the speech, and it was plain that Mr. Camphor had made a good impression. “Fine campaign speech, Mr. Camphor,” said Jinx. “Give the men as good as you give the animals and you’re cinch for the governor’s chair next fall.”

“But you ought to have told them who you are, and that you’re a candidate,” said Freddy, with a wink at Jinx. “If you can get the Senator to jam that animal suffrage bill through before election, you’ll have the biggest plurality in history.”

“Good gracious!” Mr. Camphor exclaimed. “I don’t want to be governor.” He thought for a moment. “Or do I?” he said. “You know, if I thought they’d always applaud, it would be kind of fun. But what does a governor do, Freddy? I don’t know the first thing about it.”

“Oh, he just signs bills and opens poultry shows and has his picture taken. I should think you’d get a kick out of it, Jimson. You make a dandy speech. And you’ve got the committee if you get stuck.”

“It’s always kind of scared me,” Mr. Camphor said. “At first I thought it would be nice, but then I got worried, and that’s why I tried to get out of it. But I don’t know—maybe I’d enjoy it at that.”

“You really wanted to be governor all the time, I think,” said Freddy. “Naturally, you were nervous about it. But I tell you, Jimson: if you go out and stump the state for votes for animals, in no time at all, you’ll be the best known politician in the country. Goodness’ sakes, you might even get to be president. President Camphor! Wouldn’t that be something?”

Freddy realized that the applause had gone to Mr. Camphor’s head. The pig was sure that he still really didn’t want to be governor. But if he made a lot of speeches in favor of animal suffrage, it would turn a great many animals against Simon. That was the important thing now. But he decided not to say any more about it for a while.

They had left their car on the back road, with an armed Indian to guard it, and after the meeting, Mr. Camphor drove Freddy and Jinx down to the Bean farm, then left for the Indian village. The house was dark. It was too late to report to the Beans, so the two friends went up to the pig pen. The door was locked, and they had to hammer on it for some time before a quavering voice said: “Who—who’s there?”

“It’s me—Freddy,” said the pig. “Come on, Charles, open up.”

“I—I don’t think I can move this bolt,” said the rooster. “It seems to be stuck.”

“If you moved it to bolt it, you can move it to unbolt it,” Freddy replied. “Come on, we want to get to bed.”

“Who’s we?” Charles asked.

“We is us,” Jinx said. “And for your information, rooster, my claws are half an inch long and if you don’t open up in three seconds, the first time I catch you in the open, they’ll pull your wings off. You want to go through the rest of your life as Charles, the Wingless Wonder, hey?”

“Yeah?” said Charles. “Well how do I know who you are—come banging on the door in the middle of the night. I’ve a good mind to just let you stay there.”

“Listen, Charles,” said Freddy. “Want me to prove who I am? Remember the time we were talking, and I was congratulating you on what a fine wife you had in Henrietta, and you said: ‘Oh sure, she’s a good wife, but that’s because I trained her. She used to try to run things,’ you said, ‘but after I slapped her down a few times and showed her who was boss—’”

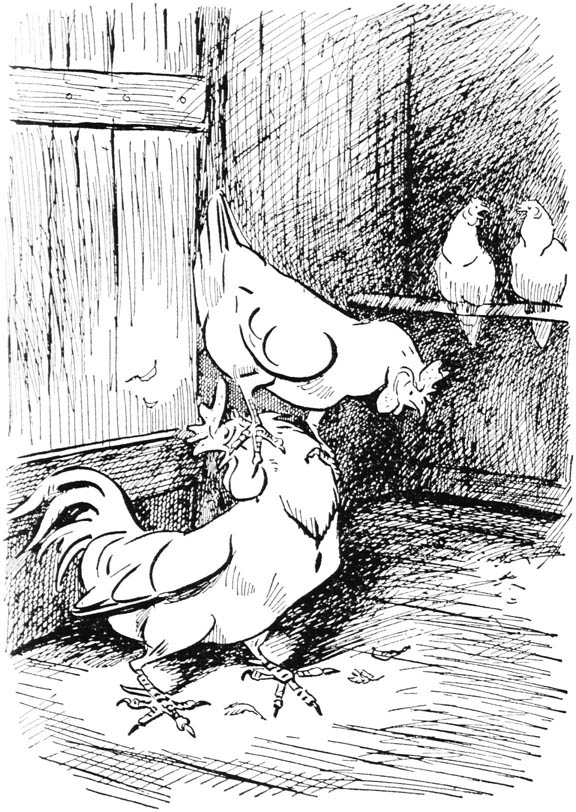

Charles interrupted with a sharp squawk. “Ouch, Henrietta!” he squealed. “Quit! Freddy’s lying; I never said any such thing.” There was a flutter of wings and more squawks; evidently, Charles was getting his ears soundly boxed.

Evidently Charles was getting his ears soundly boxed.

Freddy called: “Open up or I’ll tell the rest of it,” and at that, the bolt was quickly pulled back and the door opened.

“Let him alone, Henrietta,” said the pig, for the hen was still taking occasional swings at her husband. “Charles didn’t say that; I made it up to make him let me in.”

“Maybe you said it so he’d let you in,” Henrietta said, “but that doesn’t mean you made it up. The big blowhard! It sounds just like him!” And she took another swipe at her husband’s head with her claw.

The twenty-seven chickens, ranged on improvised perches along one wall of the pig pen, paid little attention to the disturbance; evidently, they were used to hearing their father get scolded. Even when Freddy turned on the light, only a few of them pulled their heads out from under their wings, and recognizing the familiar faces of the newcomers, tucked them back again.

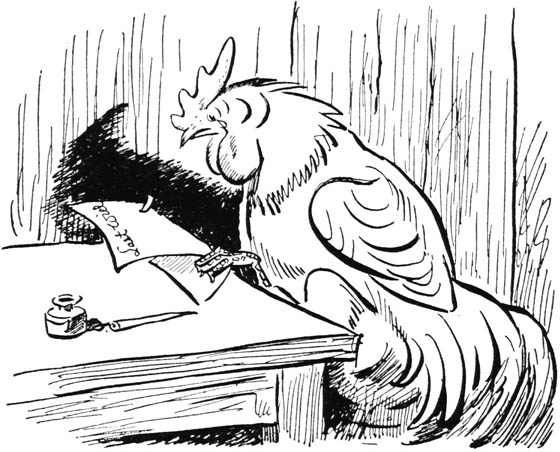

While Henrietta was still clucking indignantly at her husband, Freddy went over to his typewriter and looked at a piece of paper on which someone had started to write something. “I, Charles, rooster of this parish,” he read, “being of sound mind and not crazy or anything, do hereby declare this to be my last will and testament. To my beloved wife, Henrietta, I leave—” Here the typing stopped.

Jinx had come over and read the paper too. He and Freddy grinned at each other, and then the cat turned to Charles. “Been making your will, eh, rooster? How about leaving me a couple of million?”

“I ought to leave you a dose of poison,” said Charles. “Anybody that would go back on Mr. Bean the way you did! Anyway, what’s so funny about making my will? With these wolves around here, what chance have I got? They’ll eat me sooner or later.”

“Well, they’ll eat Henrietta too, then. So what’s the good of leaving anything to her? Better leave it to somebody that can enjoy it. Like me.”

“You feel that it is foolish of me to attempt to provide for my family?” Charles asked stiffly.

“Not if you’ve got anything to provide with,” said the cat. “But I bet that’s why you stopped writing your will where you did: you couldn’t think of anything to leave ’em.”

“I could too!” Charles snapped. “I’ve got—well, I’ve got money in the First Animal Bank.”

“Eighteen cents—you told me so yourself when I wanted you to go to the movies a couple weeks ago. Give or take a nickel—I suppose you may have picked up a few cents since then. Eighteen cents and a bunch of tail feathers—that’s what your estate will amount to, old boy.”

“Oh, quit picking on him, Jinx,” said Freddy.

“Heck, I’m just advising him,” said Jinx. “If he wants to leave his tail feathers to Henrietta, it’s all right with me. I don’t suppose anybody will contest the will.”

“Let’s get some sleep,” said the pig. “I’ve got things to do in the morning.”

But instead of going to bed, he sat down in front of the typewriter, rolled in a sheet in place of Charles’s unfinished will, and began thoughtfully pecking away at the keys. This is what he wrote. And if you ask me why, at this time and place, he wrote it, don’t expect me to explain the working of a poet’s mind.

Thoughts on Teeth

The teeth are thirty-two in number.

You’d think so many would encumber

The mouth, but they fit neatly in

Below the nose, above the chin,

Behind the lips, a double row,

So strong and sharp, and white as snow.

To keep them shining, clean and bright,

You scrub them morning, noon and night.

The teeth are used in chewing steaks

And pickled pears and angel cakes—

A list of all the things they chew

Would reach from here to Timbuctoo.

O think of all the tons of food

Which in your life your teeth have chewed!

Though birds lack teeth and cannot chew

Their victuals up like me and you,

Gizzards, it’s generally conceded,

Do all the chewing that is needed.

A gizzard no cause for discontent is:

Birds never need to see the dentist.

The use of toothpicks is thought rude

And should in public be eschewed.

To animals, both pigs and men,

Teeth only seem important when

They’re not around. If you have not

Got ’em, you miss them quite a lot.

So keep your teeth, don’t let them go;

Replacements cost a lot of dough.