CHAPTER

19

Mr. Garble’s car was in his sister’s garage, but Mr. Camphor’s car was not in the driveway where it had been left last night. “He doesn’t know that we know about the cave,” said Freddy. “That’s where he’ll be.”

“We’d better mobilize one of the dog regiments,” said Mr. Camphor. “We can attack the cave. Get the sheriff to go along and take him right to jail.”

The sheriff, who had come to the fire, objected. “I don’t want that fellow in my jail. We’ve got a nice crowd there now—nice lot of boys—no murderers or kidnappers. Mostly just burglars. They don’t want to associate with crooks like Garble.”

“Don’t you call burglars crooks?” Mr. Camphor asked.

“Why, in a way, I suppose they are,” said the sheriff. “But to tell you the truth, most of ’em don’t make much out of burglary, they just practice it mostly so they can get caught and sentenced to another term in my jail. More like a club, it is.”

“Well,” said Freddy, “maybe we can turn him over to the F.B.I. I expect that kidnapping is a federal offense, and then he’d be sentenced to a state prison—not a county jail.”

This made the sheriff feel better, and he drove them up to Mr. Camphor’s house. In the past two or three days, the dogs had rounded up a lot of the revolutionists, and the garage was now crammed to bursting with cows and horses; there were even a dozen or so on the top floor, which had at first been reserved for wolves and coyotes.

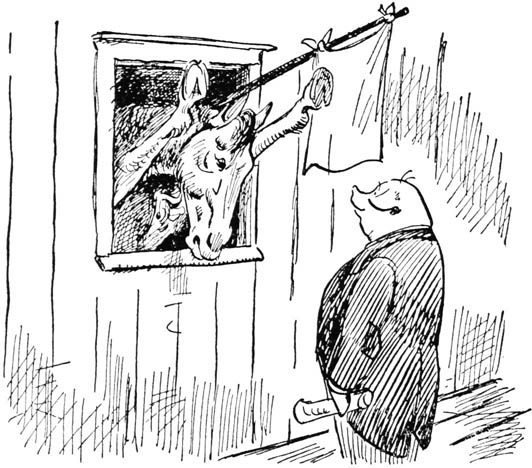

When they saw their captors looking in the window, they all began shouting at once, begging to be let out.

“Who speaks for you?” Freddy asked, and a big tough-looking bay horse pushed forward. He was Chester, formerly leader of the northern horses and cattle.

“Look, mister,” Chester said, “this Garble, he said it was going to be a bloodless revolution. What’s bloodless about it? Look at my ankles. I tell you what, pig, you let us out and we’ll promise to go back north where we came from —all of us. I’ll personally give you my word for it. We’re fed up. There’s nothing for cows and horses to eat in the woods, and if we go out in the fields, the dogs are on us. We want to go home.”

“Your revolution’s over anyway,” said Freddy. “Sure, I don’t see why you shouldn’t go.” And he unlocked the door.

Nearly all the cows thanked him when they left. The wolves simply slunk out and loped off up the lake. But Chester said: “Thanks, pal. Ever get up around Ringtail Pond, just look me up. We’ll throw you a party.” And then he too clumped off.

So then the sheriff drove Freddy and Jinx back home. The farm was free of the rebels, and the animals all piled out to shake paws and hoofs and congratulate them on their escape. Everyone knew now that Jinx had not really gone over to Simon’s party, and Henrietta in particular apologized handsomely for all the names she had called him when she’d thought him a traitor.

Mr. Pomeroy, who was getting hourly reports from the bumblebees on the mopping-up operation of the two dog regiments south of the lake, sent word for them to push on to the sand beach near the cave and wait there. “They’re meeting no resistance,” he said. “They’ll be there in an hour. Then we can attack the cave.”

“We can’t use ’em to attack the cave,” Freddy said. “Unless we want some of ’em to get shot. Garble has a pistol. And the door to the inner cave, he said, is five feet from the floor of the big hall. See if Jacob and his family are around, will you, J.J.?”

Fortunately the wasps were home, hard at work chewing up wood to build a new house. But like all wasps and most people, they were glad of an excuse to knock off work for a little while. “Specially as I’ve got a grudge against that Garble. Bent my sting on his collarbone last time we met,” he said.

So they drove up and met the dogs at the sand beach, and the dogs went up and surrounded the cave while Freddy and the wasps went in. Everything went smoothly—though perhaps not for Mr. Garble. “The door’s behind that big stalagmite,” Freddy said, and the wasps disappeared behind it. There was a short silence, then a loud yell from Mr. Garble and a terrified squeaking from the rats, and out they all tumbled. The dogs rushed in and pounced, and in no time, they were all prisoners.

—and out they all tumbled.

So Mr. Garble went off to prison and after a good deal of discussion, Simon and his family were piled into the crate intended for Freddy and shipped off, collect, to Mr. Garble’s uncle in Montana. When they got there, Mr. Garble’s uncle wouldn’t accept them and pay the charges, so they were sent back to Centerboro again, and there Mrs. Underdunk wouldn’t accept them and shipped them off again. They shuttled back and forth across the continent half a dozen times, and for all I know they are travelling yet.

Mr. Camphor’s suggestion to do away entirely with taxes was taken up by the committee, and soon the newspapers were full of pictures of him with such headlines as: “Camphor to run on no-tax platform,” “Overwhelming popularity assures Camphor victory,” and “Camphor most popular candidate in history.” For the general acclaim, the cheers and congratulations, that greeted his first appearance on the platform, had made him change his mind about running. “If they want me so much,” he said, “then I must be the man for the job.”

He did not, of course, abandon the cause of votes for animals, and when he spoke in a hall, there was always a section of seats reserved for animals, and it was always well filled. Occasionally, Freddy appeared on the same platform, pleading the cause of animal suffrage. The pig was a very convincing speaker—not eloquent, but very matter-of-fact and practical, and therefore convincing. Even then, I suppose, he had political aspirations, though it wasn’t until some years later that he actually ran for office.

Although the revolt had been suppressed, there was still a good deal of discontent among the woods animals. Campers and hunters were occasionally attacked and chased. Freddy spent the rest of that summer and fall in the woods, camping out and addressing groups of wild animals wherever he could get them together, urging them to seek a political remedy for their troubles, through votes for animals, rather than by the use of violence. Simon, he told them, stood for violence, and see what had happened to him.

With strong Republican pressure, a bill authorizing animal suffrage was rushed through the state legislature, and on election day, the Bean animals, led by Hank, carrying the flag of the F.A.R., marched into Centerboro and voted. And Mr. Camphor was elected governor by some seven million plurality over the Democratic candidate, Mr. Feebler. The animal vote was overwhelmingly Republican, and although no separate count was kept of animal and human votes, it was estimated that some twelve million animals voted.

Of course, after this, Freddy became a pretty powerful political figure. He controlled the animal vote in Otesaraga County and, consequently, since there were several times as many animals as humans, was political boss of the county. For a number of years, however, he resisted all attempts to persuade him to run for office. Some of the more influential animals in the state wanted to run him for governor, following Mr. Camphor. With the solid animal vote behind him, he was sure to win. But an animal, he felt, should not accept high political office, and although in the first few years of animal suffrage, there was a scattering of animal judges and mayors, Freddy fought the idea.

Also, Freddy remembered what Governor Camphor said to him on one of his frequent visits to Albany. “Darn it, Freddy,” the Governor said, “there’s a lot of work to this job!”

Like most lazy people, Freddy could work and work hard when he wanted to. But when he didn’t want to—well, he just didn’t want to. And he had a hunch that being governor was a full-time job. But several years later, he did run for office. He served a term as mayor of Centerboro, and it was during his administration that he solved the traffic problem which had so snarled everything up in most American cities. The Frederick Bean Traffic Plan has now been adopted in nearly every city and town in the nation. The solution was surprisingly simple: no parking within the city limits at any time. This made cars practically useless, and people gave them up and took to walking, thus improving the general health, and cutting down the cost of living. Indeed, its benefits have not been exhausted yet.

Freddy is now working on a bill to be brought up before the State Legislature, which will do away with all schools.