Chapter 6

PRIDE AND PROFITS

FROM ST. PETERSBURG TO ST. LOUIS AND BEYOND, CITIES THAT DID not have a big-league baseball, football, hockey, or basketball team have built stadiums and arenas in the hope that they would come. Smaller cities, like Rochester, New York, built stadiums for less popular sports like professional soccer, even when there was no hope the facilities could pay for themselves. Often there was no sign that team owners had put their own money at risk.

The beneficiaries of this spending pepper the Forbes 400 list of the wealthiest Americans. At least 27 of these billionaires own major sports teams. Nearly all of them have their hands out.

Arthur Blank, a founder of the Home Depot, owns the Atlanta Falcons football team. Mark Cuban, the Internet entrepreneur, owns the Dallas Mavericks basketball team. H. Wayne Huizenga, who made a fortune in trash hauling and another with Blockbuster, owns the Miami Dolphins football team. Mickey Arison, whose Carnival line carries half of all cruise passengers, owns the Miami Heat basketball team. They are just a few of the billionaire owners of commercial sports teams who have stuffed gifts from the taxpayers into their already deep pockets.

The billionaire team owners seek these payments because commercial sports is not a viable business, at least not as it is operated in America. Although baseball, basketball, football, and hockey teams are all privately held, they disclose limited information about their finances. From that data, one crucial fact can be distilled: while some teams are profitable, overall the sports-team industry does not earn any profit from the market. Industry profits all come from the taxpayers.

In a market economy, the team owners would have to adjust or cover the losses out of their own deep pockets. Instead they rely on the kindness of taxpayers to enrich themselves at the expense of the vast majority who never attend these sporting events.

Subsidies for sports teams have grown steadily. From 1995 through 2006, local, state, and federal governments spent more than $10 billion subsidizing more than 50 new Major League stadiums and countless minor league facilities. “This trend is only accelerating: Government spending on sports facilities now soaks up more than $2 billion a year,” Neil deMause, author of the book and Web site Field of Schemes told Congress in 2007.

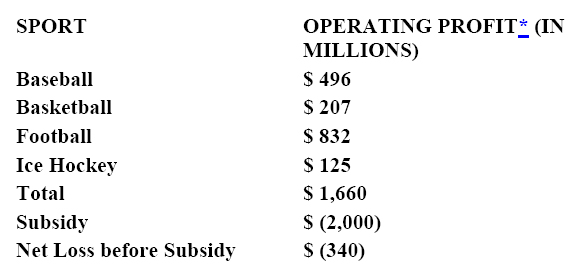

According to Forbes magazine, the Big Four sports had revenues in 2006 of $16.7 billion. They counted a tenth of that, slightly less than $1.7 billion, as operating income, which is one way to measure profits.

Putting together the estimates by Forbes and deMause shows that the entire operating profit of the commercial sports industry comes from the taxpayers. The subsidies, in fact, cover a third of a billion dollars in operating losses before this boost from the taxpayers pushes the industry into the black.

COMMERCIAL SPORTS

* Before interest, taxes, depreciation, and debt repayment

Sources: Forbes; Field of Schemes

Another way to look at these figures is to consider the subsidy a discount on the prices fans pay for tickets. There are about 135 million tickets sold by the Big Four commercial sports each year, so the subsidy equals about $15 per ticket. As we shall see, however, the subsidies do not actually flow to the ticket buyers, who instead pay above-market prices.

Also, the figures from Forbes cover only operating profits and losses, not all costs. No business or industry can continue in the long run without covering all of its costs. Not taken into account by Forbes were interest paid on borrowed money, taxes, and paying down debt. Add in those costs and the actual losses for the commercial sports industry, absent subsidies, are far greater than $340 million a year.

Subsidy economics tends to drive prices up, not down, as recipients chase subsidies more than customers. Adam Smith figured this out in 1776. He examined the subsidies in his day for commercial fishing. In his era the word bounty referred to gifts the government bestowed on the owners of herring ships. He concluded that to collect subsidies, people will appear to engage in a commercial activity. Smith wrote:

The bounty [subsidy] to the white-herring fishery is a tonnage bounty; and is proportioned to the burden [size] of the ship, not to her diligence or success in the fishery; and it has, I am afraid, been too common for vessels to fit out for the sole purpose of catching, not the fish, but the bounty.

To see how that observation applies to commercial sports, consider the failing Montreal Expos baseball team. Major League Baseball, which is a corporation jointly controlled by the team owners, bought the Expos in 2002. They kept the team in Canada for three more years, sustaining losses equal to what they paid for the team. Then Major League Baseball moved the franchise to the District of Columbia, renaming the team the Washington Nationals. The next year the league sold the team to a group of politically connected investors led by Theodore N. Lerner, a billionaire Maryland real estate developer. The Lerner group paid $450 million. Selling to the Lerner group allowed the other owners to recover what they had spent and make a profit of about $210 million. That is an extraordinary return on investment, nearly doubling the league’s money in four years.

What caused the value of the team to more than double in four years? Did the market for baseball suddenly turn red-hot with fans eager to attend? Not at all. Major League Baseball attendance in 2005 was virtually the same as in 2000, the league’s statistics show. Instead, the billionaires who own Major League Baseball went fishing for a subsidy.

Even before they moved the team, Major League Baseball sought taxpayer money for a new stadium in Washington. Eventually the city government agreed to spend $611 million on a new stadium. More than anything else, it was that subsidy that made the value of the team rise. In effect, the billionaire owners of the 30 Major League Baseball teams received a transfer of wealth from the taxpayers just by moving a failing team to a city willing to lavish more than a half billion taxpayer dollars on a new stadium.

Lerner’s group appeared to pay a lot of money for the team. In reality, they got the team for free and may even turn out to have been paid to buy the team. How? The purchase price was $450 million while the subsidy is worth $611 million, or $161 million more than the purchase price.

If Lerner’s group can capture just three-fourths of the subsidy, they will have effectively acquired the team for free. As we shall see in the next chapter, even a badly managed team was able to capture 80 percent of its subsidy, more than the Lerner group needs to make its effective purchase price zero. If the Lerner group captures more of the subsidy, then they will in effect have been paid to acquire the team.

Further, the Lerner group gets to sell the naming rights for the new stadium, a gift from the taxpayers worth many tens of millions of dollars. Citigroup, the bank and insurance company, is paying $20 million a year for two decades to have its name on the new Mets stadium in New York. A British bank, Barclays, agreed to pay the same amount once a new arena is built in Brooklyn for the New Jersey Nets basketball team, which plans to change its name to the Brooklyn Nets. (While that basketball arena benefits from free land and all sorts of tax breaks, it is mostly privately funded.)

But even that is not the end of it. The Washington Nationals have announced that when they move into their new stadium in 2008 they will raise ticket prices to almost the highest among the 30 Major League teams. The average price for season tickets will rise 42 percent, from $21 a game to $30. The most expensive seats will nearly triple to $400 from $140. Baseball teams moving into subsidized new stadiums and arenas on average raise ticket prices by 41 percent and some have doubled their average admission price, deMause calculated.

These increases will mean less spending by consumers on other recreational activities, from nightclubs and movie theaters to video arcades. One proof of this was observed by economists who study commercial sports subsidies. During the long baseball strike of 1994, business at bars and nightclubs in league cities boomed, cash registers filling with dollars not spent on expensive baseball tickets and stadium hot dogs.

What is truly perverse in the case of the Nationals is the reason that this particular team can charge so much for its best seats. These seats are not, as one might imagine, those closest to the action on the field. Instead, they are the seats that are in the sight lines of television cameras. Getting on television is valuable to politicians trying to implant a memory of their faces in the same way that shampoo bottles come in distinctive shapes, as visual clues to encourage purchases without thinking. Also, being seen with powerful officials has value for the rich and their lobbyists. A leading sports marketing consultant, Marc S. Ganis, noted that any sports franchise around the nation’s capital can command sky’s-the-limit prices for seats that enhance this symbiotic relationship between elected and corporate powers. “There is always a market for those great seats, especially those that are in the television camera angles,” Ganis said. “With a new stadium in the nation’s capital, where visibility and proximity to power is most important, these seats should sell very easily.”

Less visible are commercial sports-team finances. In 1997 Paul Allen, cofounder of Microsoft and at the time the fourth-richest man in America, with a net worth of at least $21 billion, put 18 lobbyists to work engineering $300 million of Washington State taxpayer money for a new football stadium. The total cost to taxpayers for this gift is far larger than the advertised figure. By some estimates it totals close to three times the amount advertised. Once this public gift was assured, Allen bought the Seattle Seahawks football team.

This gift came with a condition, however. The law authorizing the subsidy requires that “a professional football team that will use the stadium” must disclose its revenues and profits as a condition of its lease to use the stadium. But Allen makes public only the finances of the shell company that signed the lease, First & Goal, not the team itself. Christine Gregoire, when she was state attorney general, promised that she would enforce the disclosure clause. But after the Democrat was elected governor in 2004, she had other priorities. (The Seattle Mariners baseball team, which is subject to a similar requirement, discloses team profits.)

The huge gifts of money that wealthy owners of sports teams wheedle out of taxpayers are a free lunch that someone must fund. Often that burden falls on poor children and the ambitious among the poor. Sports-team subsidies undermine a century of effort to build up the nation’s intellectual capacity and, thus, its wealth. Andrew Carnegie poured money from his nineteenth-century steel fortune into local libraries across America because he was certain it would build a better and more prosperous nation, which indeed it did. These libraries imposed costs on taxpayers, but they also returned benefits as the nation’s store of knowledge grew. That is, library spending is a prime example of a subsidy adding value.

Many people born into modest circumstances have risen to great heights because they could educate themselves for free, and stay out of trouble, at the public library. To cite one example, Tom Bradley, the son of a sharecropper, learned enough at the local library as a boy to join the Los Angeles Police Department. He rose to become its highest ranking black officer in 1958 when he made lieutenant. Bradley went on to be mayor for two decades. But today library hours, as well as budgets to buy books, have been slashed in Los Angeles, Detroit, Baltimore, and other cities, yet there is plenty of money to give away to sports-team owners.

Art Modell, who pitted Cleveland and Baltimore against each other in a bidding war for his football team, was asked in 1996 about tax money going into his pocket at a time when libraries were being closed. It was a well-framed question. His Baltimore Ravens is the only major sports team whose name is a literary allusion, to the haunting poem by Edgar Allan Poe for his lost love Lenore.

“The pride and the presence of a professional football team is far more important than 30 libraries,” Modell said. He spoke without a hint of irony or any indication that he had ever upon a midnight dreary, pondered weak and weary the effect of his greed on the human condition. How many Baltimore children who might have become Mayor Bradleys will instead end up on the other side of the law? That may not be measurable, but that some will because of Modell’s greed is as certain as the sun rising in the east.

We starve libraries—and parks, bridge safety, and schools—to enrich sports-team owners. Yet that industry does not produce a profit from the market, although some teams may. This would not surprise Adam Smith. Likewise, he would not be shocked to learn that instead of adjusting the pay of the employees who labor in the field to reflect market realities, player wages have soared. The average baseball salary is more than $2 million annually, and a few make 12 times that much. Subsidies, Smith wrote, embolden the imprudent and encourage waste:

When the undertakers of fisheries, after such liberal bounties [subsidies] have been bestowed upon them, continue to sell their commodity at the same, or even at a higher price than they were accustomed to do before, it might be expected that their profits should be very great; and it is not improbable that those of some individuals may have been so. In general, however, I have every reason to believe they have been quite otherwise. The usual effect of such bounties is to encourage rash undertakers to adventure in a business which they do not understand, and what they lose by their own negligence and ignorance more than compensates all that they can gain by the utmost liberality of government.

A few team owners have, however unintentionally, acknowledged that building new stadiums and arenas is not a viable investment.

In Seattle, Howard Schultz, the billionaire chairman of the Starbucks chain of coffee bars, wanted taxpayers to spend $202 million to expand Key Arena, where his Seattle Sonics basketball team played mediocre games. Schultz was not a pure beggar, unwilling to risk any of his own money like so many other team owners. He offered to put up $18 million of the estimated $220 million cost. In effect, he was seeking a 12-to-1 return on his money. But at least he had some of his money in the game. Sonics president Wally Walker explained that the team needed the taxpayers to pick up 92 percent of the cost because the team simply could not afford it. “I wish there was a way for it to work privately,” Walker said.

Schultz threatened that his Sonics would fly off to Oklahoma City if he did not get this bounty. The tactic, which had worked so well for Modell and others, failed Schultz. Local voters overwhelmingly rejected his demands in 2006, a sign that at least some citizens have grown weary of making gifts to billionaires whose sports teams cannot turn a market profit. Schultz then sold the team to a group of Oklahoma investors.

Threatening to move a team unless the public pays up has become a finely developed enterprise. Arranging to collect this legal loot employs lobbyists, economists, and marketing firms, all charging hefty fees for their help in digging into the pockets of taxpayers. When Modell was playing Cleveland off against Baltimore, Betty Montgomery, then the Ohio attorney general, came up with a one-word description of this tactic: blackmail.

Such tactics work only because of one of the great economic ironies of our time. Commercial sports games are about competition, but the leagues themselves are exempt from the laws of competition.

The baseball, football, basketball, and hockey leagues control entry into the market, including who can buy a team and where it can play. The leagues deny membership to any team taken over by local government, effectively nullifying the constitutional power of eminent domain for any city that wants to buy its team to make sure it stays put. The power of eminent domain to force the sale of property is, however, used to acquire land cheaply for new stadiums, as we shall see in the next chapter.

Normally these restraints on trade would be a crime under the antitrust laws. But the Supreme Court in 1922 and again in 1953 exempted Major League Baseball from the laws of competition. The other three leagues—basketball, football, and hockey—are effectively exempted from most of the laws of business competition, as well. This exemption from the laws of competition is crucial to their power to extract subsidies. Without their power to control who can own a team and where it plays, the ability of team owners to extract subsidies would weaken and perhaps even evaporate.

The sports leagues are also exempt from the tax laws, although the individual teams are not.

In a free market anyone with the necessary capital could start a team and compete. That is just how soccer works in Britain. It also explains why Britain has so many more teams, 13 in greater London alone at last count. Their admission prices are much lower than American commercial sports teams. Even in the mega-market that is New York, commercial sports consists of just two teams each for baseball, basketball, and football, and three ice hockey teams. In a free market there would be many more.

The value of the leagues’ exemption from the laws of competition is illustrated by the odd fact that Los Angeles, the nation’s second-largest city, has no football team. So long as that city remains teamless, the owners of football franchises use the threat of moving to the nation’s second-largest market to extract money through public financing of new stadiums, rent rebates, and other official favors. Surely this would seem incongruous to the settlers who called their community El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora de los Angeles de la Porciuncula.

The Town of Our Lady the Queen of the Angels of Porciuncula is named for a small chapel run by Francesco di Bernardone, the son of a rich twelfth-century textiles merchant. As a young man sporting about with the sons of noblemen he came upon a beggar. The others refused alms, but young di Bernardone emptied his pockets and gave all that he had, following the admonition of Jesus in Luke 18 to “go and sell that thou hast, and distribute unto the poor.” This generous man came to be known as St. Francis of Assisi, the founder of the Franciscan order devoted to serving the poor, which began in his little chapel, called Porciuncula, or “little piece of land.”

In New York City, the new economic order of taxing the many to give to the richest few drew sustained support from Rudy Giuliani, who likes being called America’s mayor. Giuliani cut and trimmed the budget for parks and libraries. Over the years he slashed the very amenities and tools that enabled people to enjoy urban life and rise above their circumstances. Giuliani showed no such need for restraint when it came to funneling taxpayer money to George Steinbrenner, who made sure the mayor always had the most visible seats in the house. Giuliani, a self-described Yankee superfan, pressed for a new Yankee stadium in Manhattan, despite the economic reality that land in midtown is so valuable that all new buildings there are skyscrapers.

While high-rise office buildings create economic activity year-round, sports stadiums drain public resources while creating economic dead zones around their edges. Stadiums are to urban economies what surge tanks are to rivers.

Surge tanks are a byproduct of nuclear power plants, which generate electricity at a steady rate 24 hours a day. In the dead of night and morning, when demand for power is low, surplus electrical power is used to power gigantic pumps that lift vast amounts of water from rivers to storage reservoirs and tanks, like those on the Hudson River Palisades upstream from New York City. On hot afternoons and evenings, when demand for power peaks, the water is released, spinning turbines to generate electricity as the water flushes back into the river. Sucking water up and then flushing it back creates dead zones because fish and fowl cannot survive the fierce artificial currents. In the same way, having 50,000 or so people flow into a ballpark and then rush back out again 81 times a year kills economic activity in the immediate surrounding area. The logical place for a ballpark is where the foreseeable uses for the land are very low in value, like the edge of a city or a spit of land off the beaten track. Proposals for a ballpark in midtown Manhattan, or the downtown of almost any major city, are best filed away under “economic idiocy.”

Teams seeking subsidies come up with reports purporting to show huge economic gains if a new stadium is built. Often the claims are uncritically accepted. The crucial issue when a subsidy is proposed is the impact on the finances of the local government, known as fiscal impact. Unless the annual flows of tax revenues more than pay for the bonds being issued, then some other part of the municipal budget will suffer. Even then it will probably suffer because people’s budgets for recreation are limited. A dollar spent at the ballpark is a dollar not spent at a restaurant, bar, or other place of leisure time activity, thus transferring the jobs and economic effects from many businesses to a single sports team.

Joyce Hogi laughed when she read the reports claiming that the city would be tens of millions of dollars ahead, and her neighborhood would experience big economic gains. You don’t have to be an economist to figure out that this is nonsense, she thought. “The Yankees have been here for almost a century. Look around at how they have made the South Bronx prosper,” she chuckled. Hogi grinned at the thought that anyone would believe Steinbrenner. Besides, she noted, the new stadium would have fewer seats than the old one. And while the luxury boxes, fancy restaurants, and sports memorabilia shops might create more jobs, they were low-wage and seasonal, with no benefits or future.

New York City’s Independent Budget Office, which analyzes city spending, did review the Yankee numbers. The experts could not find any hard underlying facts to support some of the Yankee figures, which grew larger in each new report. Ronnie Lowenstein, who ran the office, concluded that any gains from a new stadium were minor, if not imaginary.

Most of the news about Giuliani savaging the budgets for public parks while working to lavish money on commercial ballparks came as discrete events in separate stories. But a few writers started connecting the dots, like Charles V. Bagli in The New York Observer and later in The New York Times, and the team of Neil deMause and Joanna Cagan writing for an irregularly published Brooklyn zine. Soon deMause made commercial sports subsidies his specialty and began tracking stadium deals for the Village Voice, eventually pulling the public record together in Field of Schemes. Much of that record is cleverly obscured so that few have an appreciation of how thoroughly market principles have been trounced by this form of socialist redistribution to the richest.

One of the most interesting tidbits deMause dug up involved an unannounced gift of $25 million of public funds that Giuliani gave the Yankees during his last days in office. The mayor gave the Mets baseball team the same gift. What the mayor did was to let each team hold back $5 million a year on their rent for Yankee and Shea Stadiums, which the city owns, and use the money to plan new stadiums. The economic effect was the same as if Giuliani had ordered the New York police to stop every city resident at gunpoint and demand six bucks.

What Giuliani kept secret, and deMause uncovered, was that the Yankees used some of this money to hire lobbyists to arrange a further taxpayer subsidy for their new stadium. The team even billed taxpayers part of the salary paid to Randy Levine, the Yankees president. During Giuliani’s term in office Levine was his economic development deputy, in effect the city official whose job was to arrange gifts from the taxpayers to rich investors who had curried favor with the mayor. Whether the Mets did the same is unknown because the city has spurned requests for records detailing how the Mets spent their $25 million.

The chutzpah required to bill taxpayers for lobbying against their interests was just one sign of how giveaways for the rich erode moral values. While our cultural myths include imaginary welfare queens driving Cadillacs, the reality is that many of our nation’s richest take from those who have much less without losing a wink of sleep.

Levine, the mayoral aide turned Yankees president, revealed one aspect of this truth in 2006, as the city council prepared to formally approve the new Yankee stadium subsidy. Levine asserted in an interview that there was no subsidy. Reminded that the Independent Budget Office for the city had concluded that public gifts were the equivalent of immediately writing the Yankees a check for $275.8 million, Levine smoothly shifted gears. He said the budget office was not competent to measure the subsidy, which he valued at “only $229 million.”

I asked Levine about the morality of this gift, whatever its size, and its coercive nature. Levine said he agreed that taxes are taken by threat of force, that they are not voluntary. So how did Steinbrenner the billionaire justify taking tax money from people with so much less? Levine, not missing a beat, replied that gifts from taxpayers to those who invest in big projects “are the way government works today.”

There it is, plain as day, what subsidies for the richest are doing to America. Levine said he did not see any other dimension to the question. The government rules say that the rich can take from the poor and the middle class, so some among the rich do, and without qualms. To those doing the taking, that’s that. Since the rules allow it, what’s the beef?

Left out of Levine’s cold calculus is how we arrived at these rules and who arranged for them. Left out is the role of campaign contributions in gaining the hearts and minds of politicians who make the rules and who know, if they want the money to keep flowing, that they must demonstrate fidelity, if not fealty, to their donors. Also left out of this calculus is any question about whether the rules we have are right, moral, or even practical.

For the recipients of money taken from others for private benefit, the rules act as a moral salve, allowing them to feel justified without examining their conduct. After all, they are just following the rules.

Remember, rules define a civilization. Rules tell us what kind of conduct is acceptable and what kind of people we choose to be. Policies that work against the general welfare undermine a society.

That Steinbrenner would eagerly stuff hundreds of millions of dollars from taxpayers into his own pockets with no qualms is not surprising. Steinbrenner has spent a lifetime soliciting subsidies with such gusto that even weakening national security has not tempered his lust for tax dollars.

During President Reagan’s term a major national security goal, aimed at intimidating the Soviets, was building the Navy up to 600 ships. Projecting more American military power across the seas required new vessels to refuel other ships at sea. The Navy awarded a contract for two refueling ships at a cost of almost $100 million each to a Louisiana shipyard. It built them on time and within budget.

Two other oilers were to be built in Philadelphia, but the contractor went broke. Steinbrenner lobbied to get the hulls towed to his Tampa shipyard to be completed. Capt. Karl M. Klein, the Navy officer overseeing the contract, flew down to Tampa to check out Steinbrenner’s shipyard. “I was shocked,” Klein recalled. “I knew it wouldn’t work.

“This shipyard was full of debris,” he said. “It was literally littered with excess and unusable materials, some of which didn’t even belong in a shipyard. There was no indication of any attempt to keep the shipyard clean.” To qualify for the contract, Steinbrenner was required to own software that scheduled the complex tasks of building a ship to ensure an orderly flow of work and payments to suppliers. But the captain said, “They had no usable scheduling software.” More amazing was that Steinbrenner was no newcomer to shipbuilding. He had spent his entire adult life pocketing subsidies under a federal law designed to make sure that the nation had the infrastructure and skills to build ships, even if it was cheaper to build them overseas.

Captain Klein started documenting all the violations and failures in Tampa. But his diligence was nothing compared to what Steinbrenner had—friends in high places. Steinbrenner met with Senator Daniel Inouye of Hawaii, a Democrat. Another Democrat, Representative John Murtha, a former Marine officer and a power on military spending, came down to Tampa. “Where’s the Navy, why are they doing this and causing all these problems” for Steinbrenner? Murtha demanded. Congress ordered the Navy to keep feeding money to Steinbrenner. Soon a special appropriation, a classic congressional earmark, sent millions of extra tax dollars to Steinbrenner, despite the fact that the ships were not being completed and Steinbrenner was not even paying his vendors.

Steinbrenner had his own version of events, one that goes to Adam Smith’s observations about outfitting for the subsidy, not the fish. “When you buy a shipyard,” he observed repeatedly, “you hire one welder, one fitter, one painter, and 12 lawyers.”

Klein thought, That’s true because you’re not building or fixing ships; you’re getting contracts and fighting not to finish them.

Before long the Navy had paid out more than $450 million. All it had to show were two useless hulls, which to this day sit rusting in the James River. The Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations held a hearing in 1995. On a claim of ill health, Steinbrenner escaped appearing. Captain Klein did show up, eager to tell the truth about Steinbrenner. Just as Klein eased into the witness chair, Steinbrenner’s lobbyist called a press conference outside the Senate hearing room. The reporters hustled out into the hallway to get that story, not Klein’s.

Three weeks later Steinbrenner was healthy enough to travel to Washington. The billionaire was allowed to testify in private, out of the glare of lights, cameras, and microphones. Harold Damelin, the chief investigator, asked Steinbrenner, “Did you ask Senator Inouye to assist you in connection with the problem you were having with the Navy?”

How Steinbrenner interpreted the question goes to the way that superrich subsidy seekers rationalize reaching into your pocket. “When I went in, no,” Steinbrenner said. “I said to every single person I went to—all I would like to have is fair treatment. I would like to be playing on a level field. I never asked them specifically, ‘Do this, get me the money, do that.’”

Of course Steinbrenner did not directly ask, any more than the serpent told Eve what would follow if she tasted the apple. Steinbrenner’s denial is on a par with the chairman of Exxon Mobil saying he does not pump gasoline and mob boss Joseph Bonanno saying he had never seen heroin. But then, could even George Steinbrenner live with himself if he had to admit that he took from the poor so that he could have even more?

In building the new Yankee Stadium, Steinbrenner yet again exploited the taxpayers, this time by getting around a law written to protect them. In 1986, Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan sponsored a law banning the use of tax-free bonds to finance stadiums, exactly the financing being used by the Yankees and the Mets. So how did Steinbrenner and the Mets owners get around that law? How did they manage to benefit from triple tax-free municipal bonds that add to the burdens of federal, state, and city taxpayers?

First, the Yankees and the Mets will not pay rent on their new stadiums, which the city will own. If they paid rent, the Moynihan law would prohibit the sale of tax-exempt bonds to finance the stadiums. But since the stadium bonds must be paid for, where will the money come from?

“These bonds depend upon an unusual arrangement for repayment,” New York City’s Independent Budget Office explained in a report. They sure do. Instead of paying rent, the Yankees and Mets bond interest and principal will come from PILOTs. That is an acronym for payments in lieu of taxes. Just as businesses that move to China have figured out how to make their tax dollars benefit themselves, so is the concept of private gain from taxes being applied with growing success within the United States by some of the richest Americans.

What happened next illustrates how thoroughly our government has been captured by the rich and powerful, how the assumption that favors must be granted to the rich permeates government today. The Yankees and the Mets went to the Internal Revenue Service for a special dispensation known as a private letter ruling. Anyone who is given such a letter can proceed knowing his or her tax breaks will be honored. This is true even if the letter is bad policy and even if it contradicts the law. These letters are issued by the IRS office of chief counsel.

IRS chief counsel Donald Korb, a lawyer as brilliant as he is contentious, gave the team owners what they wanted. Representative Dennis Kucinich, Democrat of Ohio, who wanted an explanation, summoned Korb to Capitol Hill.

Prickly as a cactus pear, Korb said that the law against municipal bond financing of commercial sports arenas was quite clear. It was not allowed. However, during the Clinton administration, someone had written regulations that created an unintended loophole. Korb adamantly insisted that the IRS did the right thing, giving the Yankees and the Mets approval under the flawed regulations. He said that once the teams got what they asked for, he did the right thing by ordering up new regulations to close the loophole.

There was just one problem with Korb’s reasoning—the IRS is under no obligation to issue a private letter ruling. Indeed, just days before Korb had complained that he did not have enough lawyers to issue all of the private letter rulings and other guidance sought by taxpayers. His solution was to ask private interests to draft new tax regulations and rulings, which government lawyers would then review and amend before making them official. Paul C. Light, a New York University scholar who studies the federal workforce, succinctly described Korb’s proposal: “It’s not the fox guarding the henhouse; it’s the fox designing the henhouse.”

Korb could have turned the fox away. He could have just deferred the Yankee and Mets requests, especially given the shortage of lawyers to issue such rulings. Then he could have sought to fix what he believed was an error in the regulations. Instead, Korb allowed the richest among us to get what they wanted, even though he had concluded that the law itself did not allow this result.

When it comes to finding ways to mine the Treasury, Steinbrenner is a master. But he has never pulled off the trick of one Texas man who championed a tax increase that flowed into his own pocket and then promoted himself as the champion of tax cuts.