FOUR

I’M NOT ONE OF YOUR LITTLE FRIENDS

Have you ever spent a substantial amount of time around a tiny human? Not “I’m the auntie who pops in for a couple hours once a year” time, but wiping butts, building castles, and catching sneezes in your mouth time. If so, then you know that those little people are positively aspirational when it comes to the art of not giving a fuck. They don’t need T-shirts or memes that proclaim their willingness to do and say exactly what they want; their lives are testaments to their philosophy.

Not here for somebody’s overdose of perfume at church? Scream that it’s making it hard to breathe just as the choir finishes singing “Now Behold the Lamb.” Incredulous that a man two parking spots over just swept garbage off his raggedy passenger seat and onto the ground? Gon’ head and loudly tell Mama that “He needs to take better care of the earth!” Not feeling the guy in the White House? Inform your classmates over lunch that he doesn’t like them because they are brown and offer up your strategy for making him be nicer. (Hint: it involves personally presenting him with a letter of advice and taking Mama along for backup in case he tries it.)

That drive to speak the truth typically evokes one of three responses in parents: rebukes, apologetic murmurs, and stifled cackles. But when we are intentional about cultivating this fearlessness in a way that balances children’s innate bent toward justice with a strong sense of self, we can raise natural leaders who ease into their personal brand of activism. The young people in this chapter are proof that as Whitney—and Randy Watson—once put it, “the children are our future.”

“I’m Not One of Your Little Friends” celebrates our children, spotlights those who are fighting for their lives, and highlights the work of the youngest activists among us.

The Accidental Activist

In the fall of 2015, eighteen-year-old Niya Kenny shot video and spoke up when a school resource officer threw one of her classmates across a room, sparking the #AssaultAtSpringValleyHigh hashtag and amplifying the national conversation about the school-to-prison pipeline. Kenny was subsequently arrested and charged with “disturbing a school.” She decided to leave Spring Valley High School and earn her GED: “I was ready to get this entire high school experience over with,” she says. Now Kenny is working with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) to challenge the South Carolina law that allowed her to be taken into custody and that sends disproportionate numbers of students of color to jail each year. Here she tells Kenrya about the day she became an activist.

What made you stand up for your classmate that day?

I can’t really say there was a thought that went through my head before I stood up and started yelling. It was just my natural reaction.

Why do you think it wasn’t a natural reaction for the adults in the room?

My guess is that maybe the adults felt they had to stick together in this situation, whether it was right or wrong. I mean, the administrator who came in before the officer, he was like, “I don’t got time to play with y’all kids today.” Like, we already different from him in his head.

What was going through your head when school resource officer Ben Fields put you in handcuffs after you stood up?

Honestly, My mama is gonna kill me. That was my biggest fear, because I was my mom’s problem child. I would get into trouble with my teachers, and I was just like, Dang, this is the first time that I never really did anything, and I just need my mama to believe me! I was just so scared at what she was going to think, and sad because I knew it would be embarrassing for her to come get her child out of jail.

How did she react?

My little sister said that when she told my mom, her initial reaction was, “I’m gonna kick her behind. I send y’all to school to learn, not to be getting in people’s business.” Because the officer told my mom, “Oh, Niya got in someone else’s business and now she’s being arrested.”

What a piece of shit. How did she react when she found out what really happened?

She was very supportive, just letting me know that everything is going to be okay. She wasn’t really telling me like, “Oh, we’re not gonna let him get away with this,” but I could tell that was her attitude. “You’re not gonna put my child in jail for no reason and then not suffer any kind of consequence.” Her biggest thing was getting justice for me, because she felt like her child had been done so wrong. That’s every parent’s nightmare.

How long were you in jail?

I was there for between eight and nine hours. That’s a full school day, in a holding area with men.

What was your first thought when you got out?

Thank God I didn’t have to spend the night!

Why do you think Solicitor Dan Johnson ultimately dropped the charge?

Honestly, I feel like there was no wrongdoing on my end, you know? He had no choice but to drop those charges. This girl was assaulted, she was taken to jail. Yelling and cursing in the classroom is disturbing school, I won’t take that away, but the environment had already been disturbed before I started protesting.

Why did you decide to challenge the constitutionality of South Carolina’s disturbing school and disorderly conduct laws with this ACLU lawsuit?

Because it’s regular kids whose lives are really affected by this law, and it’s not fair. You can be arrested and taken to jail for anything that a teacher considers disturbing their classroom, like chewing gum loudly, passing gas, burping, whatever. This is a teacher, not a judge. Oh God, now I’m just thinking about it all again. Those people made me so mad.

With good reason. What do you hope the outcome will be?

We want this disturbing schools law completely taken away. No child should be charged with disturbing the school. Charging them with that is basically just charging a child with being a child.

Did you think of yourself as an activist before October 26, 2015?

No. Never.

Did you think of yourself as an activist after that?

Yes, but not until I was told that I was one. I never knew how significant it was until the video went viral. It was just me naturally reacting to what I saw in front of me. This whole organizing world was introduced to me after the incident. I didn’t even know about the organization I intern for, African American Policy Forum. Kimberlé Crenshaw reached out and asked me to come work for her. I didn’t even know what intersectionality was before then.

What issues feel most important as you come into your activist self?

I’m definitely still focused on the school-to-prison pipeline because I have a personal experience with it. That’s always going to be an issue that I care about the most, because I had to experience that myself.

Do you want to continue working in organizing?

I think I will do this work forever. But it won’t be the only thing that I do, you know? I’m young. I want to experience everything that life has.

I fight White supremacy by working with writers on the forefront of dismantling racist, sexist, homophobic, and classist ideology. Every book that envisions a truly integrated future while challenging narratives of oppression is a meaningful intervention with the power to change minds.

—Tanya McKinnon, literary agent

“The goal of White supremacy is to make people feel less than human, to dehumanize us. As a photographer, I’m looking for the natural essence in things, something that gives you a peek into the humanity of people. This photo was part of a project called I Am Here: Girls Reclaiming Safe Spaces. But what does it mean to create and reclaim a mental safe space? There are some things that you have to be conscious of every day, or else you’ll get sucked into this world of White supremacy and never see yourself. We have to fight it, but if it takes up your whole life, then when are you supposed to live? This photo shows the power in these young, living girls, which is the power in us. They are living in their element, and they possess so much. There is so much joy in who they are—in who we are.”—Delphine Adama Fawundu

Delphine Adama Fawundu is a New York City–based multimedia visual artist whose work examines the theory of social constructivism within the development of identity.

Sidney Keys III Wants to Give the World a Book

When Sidney Keys III’s mom, Winnie Caldwell, surprised him with a visit to the St. Louis bookstore Eye See Me, he had no idea that it would make him a digital star and an entrepreneur. Caldwell shot a video of her then-ten-year-old son reading Danny Dollar Millionaire Extraordinaire by Ty Allan Jackson, and it went viral, racking up more than sixty-five thousand views. “We were like, ‘Maybe we can do something with this,’” Keys says.

That something was creating the Books N Bros club, which works to increase literacy among boys ages seven to thirteen, with a focus on African American–centered literature. “We started with this age group because boys are specifically behind in reading, and seven to thirteen is the age range where we typically stop picking up books,” Keys explains. “I don’t want reading to be something you get made fun of for doing, or something that scares boys.”

It took just one month to organize the group’s first meet-up in September 2016, where seven boys came together at the bookstore to read and discuss Danny Dollar. “I had my own lemonade stand there because in the book, the boy made a million dollars from a lemonade stand,” Keys says. “We had snacks and then we discussed the book in a little circle. It was a really cool experience.”

Keys says he was drawn to the book because Danny Dollar reminded him of someone he knew: himself. “I saw someone who looked like me. Usually that only happens with nonfiction things, like books about Martin Luther King,” he said. “Don’t get me wrong, those are good stories—but it’s nice to see fiction, just regular stories, with people like you in them.”

Keys quickly expanded Books N Bros to include a subscription service. Each month, subscribers get a book, a related worksheet, and a bookmark that nets them free treats in exchange for reading. But Keys has even bigger plans for Books N Bros: he wants to flex his entrepreneurial muscle and create an after-school curriculum so that kids can hang out and read books about Black protagonists.

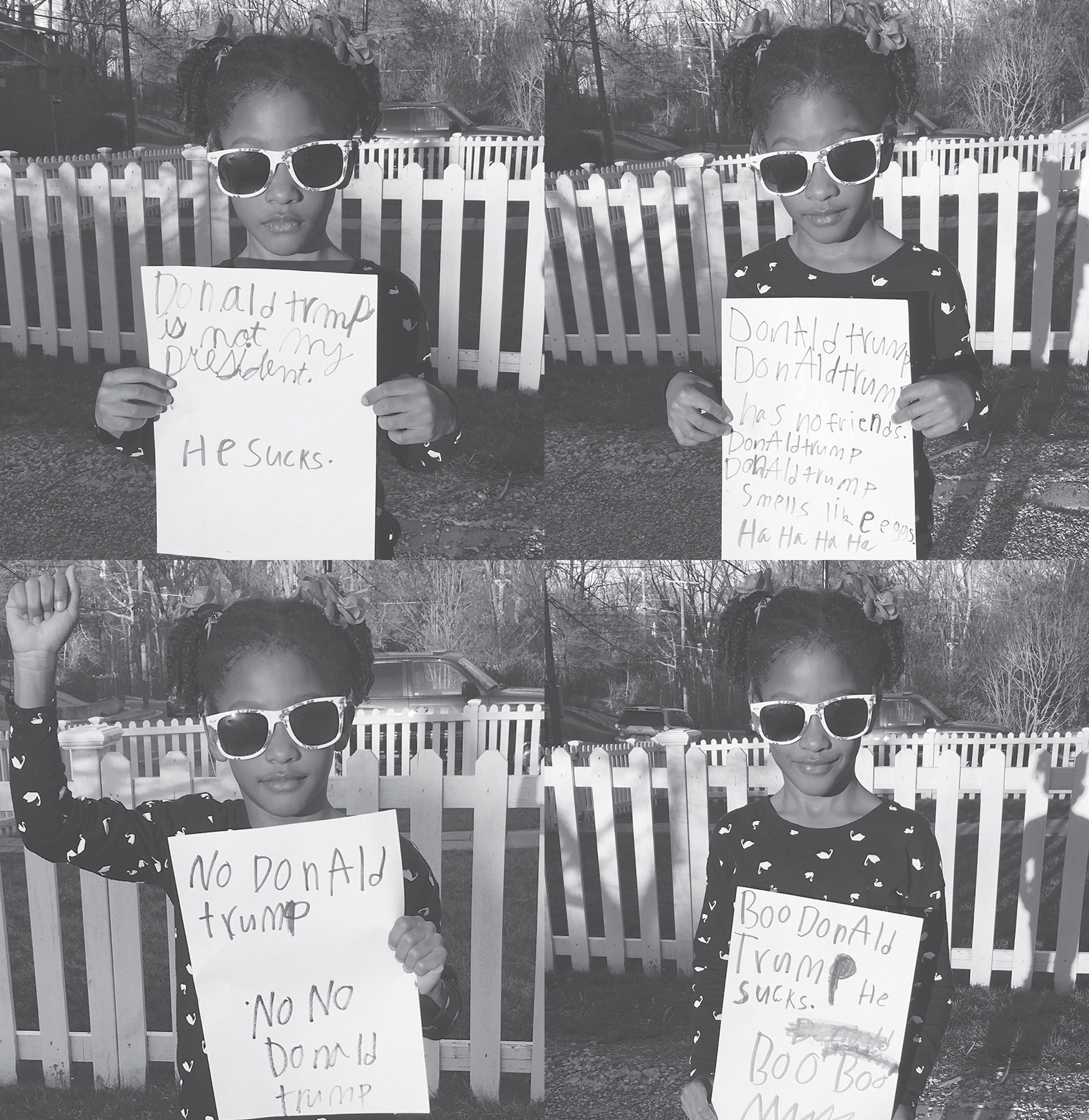

Imagine walking into an art space and seeing a group of small brown girls marching by, waving signs, pumping their fists, and chanting, “Donald Trump, Donald Trump, has no friends! Donald Trump, Donald Trump, smells like eggs!” That’s the sight that greeted visitors to an art camp in Hyattsville, Maryland, where six-year-old Saa Rankin Naasel organized five other girls—ages three to eight—for an anti-45 march. Struck by inspiration after lunch on an afternoon in late December 2017, Rankin Naasel said she organized the march “because Donald Trump is bad. He doesn’t like brown people.” The pint-sized activist said that the way he treats people makes her mad, but that marching made her feel happy because she was doing something to push back against him.

The Fight to Free Black Children

Rickell Howard Smith

I am a civil rights attorney working to dismantle the school-to-prison pipeline and eliminate the mass incarceration of Black children in America. I represent children in civil rights cases and policy initiatives, focusing my efforts on reducing racial disparities in education and the juvenile justice system. I used to think my goal was to get favorable decisions in court, help children avoid expulsion, and reduce racial profiling of Black children and their subsequent contact with the system. But time, experience, and raising two children of my own helped me realize the true purpose of my work: I fight for Black children to be free.

Freedom is defined as possessing the power or right to act, speak, or think as one wants without hindrance or restraint. But my vision for Black children is more nuanced than that. They should be free to be children and do childlike things without fear. They need the freedom to be bratty, sad, confused, self-centered, and combative teenagers without fear that the system will punish their age-appropriate behavior with lifelong or life-ending consequences. The freedom to live without being subjected to race-based trauma. The freedom to throw a temper tantrum without fear that the cops will be called. The freedom to look at their phone in class without concern that a law enforcement officer will body-slam them. The freedom to play cops-and-robbers without being killed by one. The freedom to experiment and find themselves without the suffocating intrusion of institutional racism into their lives.

I became a mother during my second year of law school, and motherhood has guided all of my personal and professional decisions since the birth of my oldest child. For me, parenthood and civil rights advocacy have a symbiotic relationship. I am, without a doubt, a better lawyer and a better mother because I am both.

As a parent, I fight for my own freedom to teach my children that they have dominion over their own bodies, the freedom to teach them that they do not have to comply with a stranger’s order. However, my ability to teach them how to be confident, strong-minded, and informed is restricted by the exhaustive list of lessons that I have to teach them to ensure that they aren’t seen as threats. I am fully aware that these lessons chip away at their ability to be carefree, but I need them to make it home. I want to be free to raise my children with the lessons and guidance necessary for them to realize their full potential and be amazing people without fear.

Working in courtrooms has taught me that Black children are especially vulnerable to becoming victims of injustice simply because of who they are. They are simultaneously subjected to age-based prejudice and systemic racism. The American legal system does not afford the same constitutional rights to children as adults. They are taught to respect and comply with authority figures at home, in the community, and at school, to be seen and not heard. The system is designed to stifle and silence them. On top of this, Black children experience the same barriers to freedom as Black adults. They often feel powerless to self-advocate because their spirits are suppressed by systemic racism, and they lack the legal protections and opportunities to advocate for themselves.

Case in point: Even though the American juvenile justice system has been undergoing systemic reform for nearly twenty years, Black children have barely benefited from those efforts. National youth incarceration rates have dropped significantly over the last decade, but racial disparity in the juvenile justice system continues to grow as Black children are victimized by systemic racism. They face harsher school discipline consequences, at higher rates, and they are more likely to be arrested, charged, and punished severely for engaging in the same age-appropriate behavior as their White counterparts.

Of course, this is no secret to Black folks. We don’t need data reports to tell us what’s happening in our own communities. But being entrenched in this work reminds me that no matter how well they were raised, or how wealthy or educated their parents are, our precious kids are not immune from this. This understanding shapes the way I advocate for all Black children and raise my own. Rearing children as a civil rights advocate makes me view everything through a dual lens. As an advocate: how do I use the outcome of this court case to help Black children be free? As a mama: how will this make things better for my babies?

I once thought that being a Black woman civil rights attorney was the height of my personal revolutionary action. Now I know that parenting my children is the most revolutionary thing that I can do in this world. Parenthood transformed me from a lawyer to a freedom fighter for Black children. They need all of us more now than ever. They need our collective love and support. They need us to see them as children. They need the change agents in the world to focus on their voices, needs, and desires. They need us to create space and opportunity for them to advocate for themselves. They need us to tear down the suffocating force of systemic racism so that they can be free. So they can live.

Rickell Howard Smith is the litigation and policy director at a nonprofit child advocacy organization. She specializes in civil rights litigation aimed at reforming the criminal and juvenile justice systems and was a 2017 Youth Justice Leadership Institute Fellow of the National Juvenile Justice Network.

I fight White supremacy by teaching my children about Black power, excellence, and magic. The same way that White supremacy is a learned behavior, our children need to learn that their ancestors were great leaders and innovators whose contributions impact the world in a major way.

—Khalfani Walker, dentist

Author and Journalist Denene Millner on Why She Has Dedicated Her Career to Making Books for Black Children

When I got pregnant with my first baby, I promised that my child wouldn’t have to spend the most impressionable part of her life longing for herself in literature. The books I publish through Denene Millner Books all celebrate Black children. What I love about these books—including Crown: An Ode to the Fresh Cut, There’s a Dragon in My Closet, and Early Sunday Morning—is that they shine a light on our babies and their everyday lives. There’s no focus on civil rights icons. No big-ups for famous jazz singers or sports figures. No nods to slavery. There’s no overcoming or struggling to get by, or Black “firsts” we force children to revere. They are just good old-fashioned tales about the lives of little human beings with brown skin—my love letter to children of color who deserve to see their beauty and humanity in the most remarkable form of entertainment on the planet: books.

QUESTION, ANSWERED

Much of who we are starts when we are tiny humans. So we explored the question: what’s your activism origin story?

Kenrya

A play in four acts.

Act I

It’s 1989 at Aurora Road Elementary School in Bedford Heights, Ohio. I’m in the third grade, and I am decidedly my father’s child. He had settled into paycheck-to-paycheck-class life in a suburb across town from my cousins where we could get a good public school education and still see Black people, but before I was born, he was a beret-wearing, rifle-toting, school breakfast program–starting Black nationalist. And though his strong moral compass meant that he left that organization when internal corruption surfaced, he never stepped away from his love for his people and contempt for the system that brutalized us. Accordingly, he was very honest about what it meant for my sister and me as Black children growing up in a nation that has, from the very beginning, treated us as less than human. So after I learned from him while I was still in single digits that this supposedly “indivisible” country was fueled by disregard for our lives and that the actual words of the Pledge of Allegiance were drafted with xenophobia and White supremacy in mind, I decided that I was not pledging my allegiance to shit, thanks. Every morning the entire school says the pledge as someone recites it over the intercom system. Every morning I stand, hands at my sides, mouth closed. No one says a word to me about it.

Act II

It’s seven years later, and I join the NAACP because my friends are in the youth chapter and it looks fun. We hold a ton of voter registration drives at skating rinks and parks, but the first time I feel like an actual activist is during a national convention. That’s when I participate in my first sit-in. The details are hazy—I’m old, y’all—but the national board is planning to reduce funding for youth field coordinators, the folks who provide training and support for local youth chapters like mine. Being a kid in this elders-dominated space feels like engaging in a never-ending game of Mother May I? The organization is granted giant steps forward for publicly holding up young people as the next front in the movement. But when it withholds the support we need to actually lead, it feels like we’re bounding backward when no one is looking. So we use the tactics of those who came before us and hit the floor outside the boardroom, vowing to stay there until they make it rain. I go on to hold leadership positions with my college NAACP chapter.

Act III

The summer after my freshman year at Howard, I spend my afternoons interning at an advertising firm in Cleveland where I am, of course, the only Black person in the entire office. One Friday, my supervisor, a young White woman, gives me a task. “Can you please take this box of client contacts and put it in alphabetical order?” I cheerfully accept the box of maybe one hundred notecards, sit at my desk, and proceed to put them in order in a few minutes. When I arrive back at her cubicle with the cards, she looks confused. “Do you have a question?” she asks. “No. I’m done,” I say, handing her the box. “Done?! How?” she asks, still puzzled. “It was alphabetical order,” I say, eyebrow raised, also puzzled. “Wow! You’re amazing! Thanks so much for doing this so quickly!” she says. I squint at her, then walk back to my desk, wounded, but not really understanding why. The soft bigotry of low expectations is some insidious shit.

Act IV

It’s 2014 and I’m somebody’s mama. Police shootings of unarmed Black men and boys like Eric Garner and Michael Brown are forcing us to beg the world to assign value to our lives, and the National Action Network holds the Justice for All march in Washington, DC. I hit the ground with a couple of my linesisters and our kids and try not to cry as they march—literally, because my three-year-old isn’t fucking with you if you’re not high-stepping it through the streets—holding handmade signs that read, OUR LIVES MATTER. I tell an interviewer that day: “I wanted her to know, even at her young age, that we are our most powerful when we are united. I wanted her to see what it looks like when thousands of people come together to advocate for themselves. I wanted her to feel the energy that is generated when people have had enough and decide to do something about it. So we took to the streets.”

Akiba

I did a decent amount of community service growing up. I participated in walkathons, collated stuff for my mother’s meetings, served as a peer educator at Planned Parenthood, and took part in an “Africentric” curriculum effort called African Youth for Education. On the get-shine side, I sang the Negro National Anthem at an anti–Desert Storm rally. And because I was “conscious,” I was also quoted in the newspaper, once for citing the fatal flaws of an all-White newsroom and once for pointing out that “a dangerous psyche of materialism” explained why a Black girl had been shot over a pair of gold earrings.

Still, it wasn’t until my senior year of high school that I attempted to organize people to fight White supremacy.

The public school my sister and I attended was considered the best in the city and one of the top in the state of Pennsylvania. Coming out of a predominantly White, single-sex prep school, this elite public school I will call Super Selective College Preparatory Magnet Academy (SSCPMA) had many appealing features: boys, boys who were Black, and a bevy of Latinx, Asian, and South Asian kids.

But in this public school, where I desperately wanted to fit in, I was incensed by the racism of some of the teachers.

First, there was a phrase I only saw Black kids being disciplined with: “This is not your neighborhood school! This is SSCPMA!” Within this context, “neighborhood school” was coded language for an inferior “ghetto” institution that accepted just any old person. The trope suggested that Black students should go back to their natural habitat—a school with low standards.

In another case, an elderly White teacher who I was told had tenure would routinely make blatantly ignorant mistakes about Black history. No, sir. Malcolm X was not murdered in 1950. And slavery didn’t end after a “few decades.” When I tried to clarify, he would kick me out of class.

Another teacher, we heard, was overtly racist. He once told a Black student eating an apple that she should be eating a banana instead. Another time he told a Black girl wearing a headwrap that she looked like Aunt Jemima.

My headwrap-wearing, conscious Afrikan crew had been commiserating about the subtle racism of the school, but the Aunt Jemima comment compelled us to do something.

I truly don’t remember whose idea it was to distribute daily anonymous flyers demanding that racist teachers be fired or at least forced to undergo diversity training. I also can’t recall whose idea it was to tell students to wear black armbands in solidarity with our movement and come to a speakout we’d be holding at the end of the week.

I do remember writing the text for our missives, which I photocopied on hundreds of pieces of colored paper at my mother’s job. Each installment included a subversive quote that could be read as empowering, vaguely threatening, or a declaration of race war, depending on your vantage point. Apparently White students into neo-Nazi punk culture took our movement as a war cry—we heard they were planning to bring knives to our speakout.

After we promoted it with a week’s worth of flyers secretly dropped in various locations throughout the school, the speakout was lit!

As planned, we in the vanguard of the movement sanctioned our racist teachers and called for them to be fired or retrained. But somehow the discussion drifted to interpersonal racism among students. (This is my adult retelling. I didn’t know the phrase “interpersonal racism” until I was like forty.) One of the Nazi girls started an impassioned speech about how scared she was about what “you people are doing here.”

“You people? ” we vanguards hissed.

“Let her explain!” said unaffiliated centrists of color in the room. The girl got to make her point about how “we” wouldn’t get anywhere if we focused on race so much. People clapped. I felt sick, then checked out.

After our speakout ended, I found myself enveloped in the arms of a non-vanguard brother who had helped us set up the chairs. “We did it!” he said joyously.

“We did not do it at all,” I said. “We let that racist White girl disrespect us.”

He looked at me strangely and said, “You’re never satisfied.”

A few days later, it got back to me that at least two girls in our little Afrikan organizing crew were calling me full of shit and saying that I only “did this to get famous.” I was so crushed by their betrayal that I got sick with flulike symptoms.

I was out of school with the flu and what was very likely a bout of depression so long that I missed the school gospel choir’s big performance at the Gallery Mall downtown. I was a soloist and had been plotting for weeks how I would impress this college-age gentleman who designed and sold conscious Black T-shirts at the mall. Not only had organizing made me sick, but it ruined my (imagined) chance with T-shirt jawn.

Months later, the four White Los Angeles police officers caught on video camera savagely beating Black motorist Rodney King—Stacey Koon, Laurence Powell, Timothy Wind, and Theodore Briseno—were found innocent. It was an early ’90s precursor to today, when ubiquitous cell-phone and police video footage of officers beating, Tasing, choking, setting up, sexually assaulting, and fatally shooting Black people ensures the trauma of both victims and viewers—and too often leaves the apathetic justice system unmoved.

As Los Angeles burned, students of all races held a walkout. School authorities accused me of orchestrating the protest, but it certainly wasn’t me. It was, however, the moment when vanguard and oblivious alike agreed that there was something very, very wrong with America.