Samuel Beckett was born in Foxrock, a select and eminently prosperous southern suburb of Dublin, in April 1906. He was of solidly Protestant middle-class stock. His father, William, was quite probably a descendant of Huguenot refugees fleeing religious persecution in France in the late seventeenth century.1 If so, however, the French connection had long since ceased to count. William Beckett was an affluent, successful building contractor. He became accustomed to a certain milieu and style of life, climbing just about as high as was possible for a scion of the Dublin Protestant bourgeoisie. The Becketts’ house, Cooldrinagh, was well-appointed, with quarters for servants, a tennis court, lawns and a stable. William was a member of the powerful, Protestant-dominated Freemasons and the exclusive Kildare Street Club, bastion of the Anglo-Irish and famous for its aristocracy, claret and whist.

We should distinguish carefully between the Dublin Protestant middle-classes and the landed Anglo-Irish.2 But Beckett’s mother, May Roe, was of a family who had formerly been landowners. Though the family had gone into decline, producing clergymen, her father still held tenanted land. The class to which the Becketts belonged identified with England, and tended to share the Anglo-Irish gentry’s conviction of their own superiority. They had little or nothing to do with the Catholic majority, to whom their attitude was condescending at best. Their unionism, ‘their loyalty to the Crown and the Union Jack’ was ‘automatic and unquestioning’.3 In his German Diaries, Beckett remembers a Union Jack handkerchief from his childhood (GD, 6.10.36). As we shall see, though loyalty was one of his more conspicuous traits, the Unionist adherence was not one that he was greatly concerned to sustain.

Unionist allegiances were not the only feature of his background which he was later to shrug off, or to which he was to prove indifferent. His parents themselves, however, certainly mattered to him. William seems to have loved his two sons, Frank, the elder, and Samuel, straightforwardly, and the feeling was straightforwardly reciprocated. May was religious, moody, turbulent, demanding. Samuel’s relationship with her was complicated, and at times conflict-ridden, but there was obvious closeness in the torment, and she was to loom large in his psychic life for a very long time. When the poet John Montague asked him whether he had found much that was worthwhile on his journey through life, he singled out his mother and father, if in a characteristically sardonic tone, and in less than cheering terms. ‘Precious little’, he replied. ‘And for bad measure, I watched both my parents die’.4

Beckett’s educational career was not untypical of a product of his class. He went first to a genteel kindergarten near Cooldrinagh, where he mixed with children from very similar backgrounds to his own. Earlsfort House School, again in Foxrock, was equally respectable, but admitted Catholic children. However, his most significant early move was to Portora Royal School. Portora was in Enniskillen, in Northern Ireland. It was one of five Royal Schools. These had been founded in 1608, by Royal Charter, in the wake of the Tudor plantation of Ireland. James I‘s wish was that ‘there shall be a free school at least in each county, appointed for the education of youth in learning and religion.’5 In the event, five schools were established, providing an education to the sons of local merchants and farmers during the plantation of Ulster. They were sites for the production of a colonial class, enclaves of civilized value in the savage wilds. Portora eventually turned out large numbers of colonial administrators. Though diluted by the passage of time, the sense of purpose this involved still clung about the school that Beckett attended.

‘The Eton of Ireland’: Portora Royal School, Enniskillen, Co. Fermanagh.

But Beckett began at Portora in 1920. Portora was sometimes known as ‘the Eton of Ireland’. It had much of the ethos of an English public school. If the civilized virtue of the English presence in Ireland can ever be categorically distinguished from barbarism, 1920 was not a good year to try to do it. For Ireland was in the grip of the Anglo-Irish War. The New Year had begun with the recruitment of the Royal Irish Constabulary Reserve Force, otherwise known as the Black and Tans, followed (in July) by the ‘Auxies’, the Auxiliary Division of the RIC. Most of the recruits were British, many of them First World War army veterans. In Roy Foster’s phrase, they behaved like ‘independent mercenaries’.6 Initially, at least, the Black and Tans were not subject to strict discipline, and avenged their losses by burning and sacking towns and villages and conducting arbitrary reprisals against the civilian population. The Auxies were if possible more brutal. Together with the Black and Tans, in December, they responded to an ambush by destroying Cork city centre. Thus ended a year that had also witnessed ‘Bloody Sunday’ (21 November), on which the Black and Tans had started firing into a football crowd. In Ulster it self and above all in Belfast, the year had also seen anti-Catholic pogroms.

Of course, the other side in the war also bore responsibility for its share of the general mayhem. But it did not preen itself on being one of the world’s great civilizing powers. Nor did it come fully armed with institutions like Portora that boasted their commitment to ‘honour, loyalty and integrity’.7 Beckett had little respect for the kind of elite the school produced: when, for a very short spell in 1928, he taught at (the more recently founded, but similar) Campbell College, Belfast, he was critical of certain students. The then headmaster, William Duff Gibbon, MA, DSO, MC, suggested he remember that the boys at Campbell were ‘the cream of Ulster’. ‘Yes, I know’, retorted Beckett, ‘rich and thick’.8 His name does not appear in the old Campbellians’ college history.

Beckett in the Portora Royal School cricket team in 1923 (seated, at right).

More importantly, like the writer who was to become his great mentor, Joyce, Beckett was painfully aware of the obscurity of any line supposedly demarcating civilization and barbarism, and wilfully blurred it in his work. The voice of the one insistently reverses into the voice of the other. Beckett’s most illustrious predecessor at Portora was Oscar Wilde. However, he would not have found Wilde’s name on the school honours board. It had been deleted after the scandal and trial of the 1890s. The school website still remarks on Wilde’s infamy. The young Beckett was a fine sportsman, and seems to have accommodated himself quite smoothly to life at Portora. Yet his work amounts to a far more comprehensive assault on the spirit of Portora than Wilde’s. Beckett’s characters are remarkable for their lucid, disabused refusal to jack themselves up to flattering levels of self-deception. They owe some of their acrid tone and hilariously bleak clarity of vision to what Beckett saw around him in and after 1920, and the contradiction between Portora and its environment.

Portora had strong ties with Trinity College, Dublin. If Portora was a distinguished Anglo-Irish educational institution, TCD was the most eminent one. Founded in 1592 by Elizabeth I, it was the traditional university of the Protestant Ascendancy, Ireland’s best (and for a long time its only) university institution. In principle at least, it had opened up to Catholics from 1794. But it did not feel open. The great Irish Catholic genius of his age, James Joyce, would not even have entered its superb library.9 A gulf yawned between Trinity and the Catholic majority in Ireland, not least the Catholic intelligentsia, that was not merely religious, cultural and economic but also one of class. Some sense of what was at stake in this can be gleaned from J. P. Mahaffy’s view of Joyce as ‘a living argument in favour of my contention’ that it was a mistake to establish a university ‘for the aborigines of this island – for the corner boys that spit in the Liffey’.10 In the early twentieth century, Mahaffy was one of the great Trinity luminaries, its Professor of Ancient History and, eventually, its Provost. He was a learned, gifted, eccentric and genuinely witty man. This did not save him from certain automatic responses, or the failures of intelligence they implied. Joyce and Beckett worked partly to destroy the assumptions underlying Mahafffy’s ‘contention’, the one from without, the other from within.

Beckett attended TCD from 1923 to 1926. He went up to study for an Arts degree. Here he came under the influence of another imposing Trinity character, Thomas Rudmose-Brown, Professor of Romance Languages. In some ways, Rudmose-Brown rather resembled Mahaffy (though Mahaffy appears to have viewed him with some contempt). Rudmose-Brown was a snob who claimed a family coat of arms and royal descent, and vituperated against the consequences of Catholic majority rule. But he was also a wayward man, never really a member of the Trinity establishment. He was decisive for Beckett’s development. Before Trinity, there was little or nothing in Beckett’s Protestant background and education that might have nourished imagination or a speculative cast of mind. The claim that ‘Rudmose-Brown made an intellectual out of a cricket-loving schoolboy’ does not seem unduly extravagant.11 The professor, whom Beckett referred to chiefly by his faintly Woosterish nickname of ‘Ruddy’, turned him in a vivifyingly un-Woosterish direction. For he particularly fostered Beckett’s love not only of France, but of French intellect and French literature. In effect, he made it possible for Beckett to exchange one version of himself for another.

Rudmose-Brown, however, did not instil the will to change. This only gradually took hold of Beckett. But it had its roots in his social position in Ireland, and the historical circumstances that gave that position a very precise form at the time he was growing into adulthood. The Anglo-Irish War came to an end with the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty on 6 December 1922, and the birth of an independent Ireland. The trouble was that, for many, the new, independent Ireland was not independent enough. The Treaty granted Ireland only the freedom of a British dominion, gave Britain continuing rights in security and defence, and proposed a Boundary Commission that might pave the way to a permanent separation of Ulster from the Republic. The real sticking-point, however, was that the Treaty required an oath of allegiance to the British crown. This was too much for those who increasingly became known as the irrecon-cilables, notably Eamon de Valera. A split between ‘Treatyites’ and ‘anti-Treatyites’ was soon inevitable, and was followed by the Irish Civil War of 1922–3.

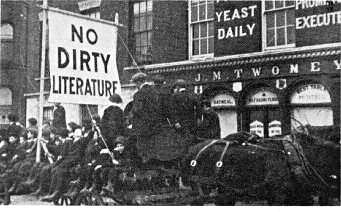

The Treatyites won. De Valera was arrested. William Cosgrave’s government and party rapidly consolidated their power. Since the anti-Treatyites did not take up their seats in the Irish parliament, the government enjoyed considerable legislative authority. Of course, this tended to provoke resistance as much as quell it. There was an army mutiny, for example, in 1924. It was nonetheless clear that, whilst markedly reluctant to break with the political and administrative models of the old colonial master, the new government represented a triumph for the Catholic bourgeoisie and the patriots. It was also a triumph for the Roman Catholic church in Ireland. Whilst, as was traditional, the Church supported the government rather than those who dissented from it, for its part the State did not question the Church’s authority in matters of health, education and sexual morality. Before long, the Irish government was passing singularly dismal laws on divorce, contraception and censorship. The Censorship of Films Act, with its restrictions on material ‘unfit for general exhibition in public by reason of its being indecent, obscene or blasphemous’, became law as early as 1923.12 This was very much in line with the Church’s proclamation that ‘everything contrary to Christian purity and modesty’ in modern cinema was alien to Catholic and Irish ideals, as though the two were in principle one.13 The same kind of thinking applied to literature, though Ireland did not get its Censorship of Publications Act until 1929.

‘Contrary to Christian purity and modesty’: an Irish demonstration in the 1920s.

In another of the greyly serendipitous moments with which Beckett’s life seems punctuated, he returned from Northern Ireland in 1923, when it was about to become a haven of sorts for a residual, Protestant-dominated culture in Ireland, to the South, at a time when its Protestant culture was entering a final, twilit phase and the new Catholic culture was failing to offer any adequate replacement for it. Some Southern Protestants – W. B. Yeats, Andrew Jameson, Henry Guinness – were to play a very important part in the new Republic. But these were men of a very particular class or stamp and were already distinguished figures. In fact, Ireland had been leaking Protestants since before the First World War. The Anglo-Irish War and the Civil War only aggravated the trend. From the death of Parnell onwards, Protestant Ireland more or less consciously knew that it was playing an endgame, that the vector of history was no longer on its side. From 1923, it was clear that the power of Catholic nationalism, the Catholic bourgeoisie and the Catholic church was steadily growing and would continue to grow. The formation of the Irish Free State deprived the Beckett household of any politics ‘except a silent and unexpressed loyalty to a regime which had vanished forever’. They therefore ‘lived in a sort of political vacuum’.14

At the same time, however, in the period running from Beckett’s birth in 1906 to his first major departure from Ireland in 1928, what Lionel Fleming called the question of ‘identification’ became crucial to the Anglo-Irish Protestant middle classes.15 One of the recurrent themes of Dublin-suburban Protestant middle-class writings after 1922 – Fleming’s Head or Harp, Terence de Vere White’s A Fretful Midge, Patrick Campbell’s An Irishman’s Diary, Brian Inglis’s West Briton, W. F. Casey’s The Suburban Groove, Niall Rudd’s Pale Green, Light Orange, Lennox Robinson’s The Big House (a play) – is just how decisively the Anglo-Irish Houyhnhnms had separated themselves off from the Yahoos, how far they had asserted and confirmed their identity through militant segregation, or what Rudd calls ‘an unstated system of “yes’s” and “no’s”’.16 These people ‘remained almost unaware of [the] other Ireland’.17 Tramps often came to the Flemings’ door, as they did to the Becketts’, trying on old boots and trousers.18 The door itself nonetheless marked a frontier between two worlds.

But the other Ireland ‘was coming into its force’.19 From 1922 onwards, the Protestant middle classes could hardly ignore this. They developed an increasingly uneasy if ambivalent sense of the need to make an effort, to bridge the gulfbetween the worlds. Undoubtedly, they frequently resented ‘the State’s effort to impose what to us was an alien culture’.20 The young Beckett himself was occasionally capable of expressing this resentment. All the same, the distance that separated Anglo-Ireland from England was growing. By the late 1920s, Beckett’s class might hate the new Irish national anthem, the Black and Tans, Gaelic sports, the Belfast bowler, de Valera and ‘humbuggery’ (the vice anglais) with equal vehemence.21 As Robert (‘Bertie’) Smyllie, distinguished editor of the Irish Times, insisted, the Protestant middle class had to reach some kind of accommodation with the Free State.22 Thus middle-class Protestants who remained in Ireland tended to experience a long, slow erosion of Anglo-Irish attitudes.

Beckett was to leave Ireland. This does not necessarily mean that his work is not partly an allegory of ‘the process of [the] decay’ of Anglo-Ireland,23 or an allegory of Irish Protestant self-effacement and destitution after 1922. But the question of identification is most obviously crucial in his early collection of stories More Pricks Than Kicks. This is set in Dublin and focuses on Dublin milieux. It is concerned with the (intellectual, social and sexual) opportunities the city appears to offer (or fails to offer) to a clever young Protestant Irishman in a newly independent Ireland. The protagonist, Belacqua, is a Dublin, middle-class, Protestant intellectual. This places him in a profoundly equivocal position relative to Ireland in general and Dublin in particular. Heedlessly, with a quite conscious, deliberately cultivated indifference, the book freewheels among sometimes starkly contradictory positions.

Irish Protestant destitution: the ruins of a ‘big house’, 1923.

‘La Mancha’, site of the 1926 ‘Malahide murders’.

Belacqua is deeply uncertain how far to shrug off the culture from which he stems. Take the first story in More Pricks than Kicks, ‘Dante and the Lobster’. The figure of Henry McCabe, the so-called Malahide Murderer, is central to it. McCabe had worked as the gardener for a well-to-do family in Malahide, on the outskirts of Dublin, with two household staff. On 26 March 1926, he summoned the Civic Guard, telling them that the house was on fire. The Guard discovered the six bodies of the family and staff. The authorities deduced that the house had been set on fire intentionally, and the bodies showed traces of arsenic and violence.

McCabe was accused of the murders. His arrest, trial, and appeal caused a sensation in Ireland and received extensive press coverage. The evidence was at best inconclusive, and the prosecution’s explanation of the accused’s motives were ludicrously weak. Nonetheless, McCabe was sentenced to death. ‘Dante and the Lobster’ tells us that the sentence caused outrage, leading to a ‘petition for mercy’ which was ‘signed by half the land’ (MPTK, p. 17). This is doubtful. What is most important is that Beckett depicts the Ireland of1926 as divided down the middle over a legal case involving capital punishment. For Irish republicans and nationalists were very much exercised by questions of the law in Ireland. Ireland had had an ancient legal system of its own, Brehon Law, which survived from the first English invasion in 1169 to the seventeenth century. From 1169 onwards, however, it was increasingly replaced by the colonizer’s law, Crown Law, and the British system of judicial procedures, procedures for the establishment of guilt and innocence and for punishment, including capital punishment.

In dissident and nationalist Ireland, however, there persisted a conviction of the foreignness of British law, the fact that it had been imposed on an unwilling people. This conviction was much enhanced by nineteenth-century historians, antiquarians and scholars, who rediscovered Brehon Law. This led to the creation of a Brehon Law Commission which produced Ancient Laws of Ireland, a six-volume set which made it possible to understand what Irish legal tradition had been before colonization, and therefore to imagine what it might have been without the colonial presence. In particular, as opposed to Crown Law, Brehon Law had had no state-sponsored system of enforcement. The issue over which Ireland was most divided in the 1920s was how far it ought to throw over, to finish with the presence of English traditions, and allegiance to the British Crown. The question of continuing with a state-administered death penalty was a question of adherence to Crown Law. Broadly speaking, to call British legal tradition into question was nationalist, to defend it a position identifiable with the English in Ireland, including Beckett and Belacqua’s class.

It is thus no accident that More Pricks Than Kicks begins with a question involving Crown Law. Henry McCabe died on Thursday, 9 December 1926. ‘Dante and the Lobster’ is set on 8 December. The story traces Belacqua’s conversion to a position on the death penalty that is strictly more of a nationalist than an Anglo-Irish one. At the beginning of the story, Belacqua is sufficiently indifferent to MacCabe to cut into a loaf of bread on his picture in the newspaper. By the end of the story, by contrast, he has grown more rueful:

And poor McCabe, he would get it in the neck at dawn. What was he doing now, how was he feeling? He would relish one more meal, one more night. (MPTK, p. 20)

‘Mercy in the stress of sacrifice, a little mercy to rejoice against judgment’ (ibid.): this is the emphasis on which the story ends. In ending it thus, however discreetly, Beckett calls into question a philosophy of law bequeathed to a newly independent Ireland by its colonizer.

But if, at the end of the story, we see a Belacqua shrugging off one of the habits of thought more or less automatic in his class, elsewhere, we see him abundantly continuing in those habits. Furthermore, his sympathy for McCabe is itself finally ambivalent. He can properly feel for a creature abruptly thrust into sudden death only in the instance of a living lobster about to be boiled, on to which he displaces any nascent emotions he may feel on McCabe’s behalf. Indeed, in the very last line, Beckett himself even has to correct Belacqua’s responses. Belacqua shrugs off the impulse to care: ‘Well … it’s a quick death, God help us all’. To which his author retorts, smartly, ‘It is not’ (MPTK, p. 21). Belacqua is finally non-committal, lukewarm, and therefore mired in unimportance.

In the late 1920s, Belacqua is placed in a profoundly equivocal position relative to Ireland by virtue of being a middle-class Protestant intellectual. There is a good deal of fun, in More Pricks Than Kicks, at the expense of the Anglo-Irish Revival’s literary stock-in-trade. But if Belacqua treats various features of Anglo-Irish revivalist culture with scorn, he is equally dismissive of the new national culture. The name of Patrick Pearse half puts him off the ‘most pleasant street’ that bears it (MPTK, p. 43). Law and order are maintained by brutish Civic Guards. One of the dominant features of newly independent Dublin is its ‘Star of Bethlehem’, advertising that notable British export, Bovril (MPTK, p. 53). The narrator adds that philistines have clamped a ‘glittering vitrine’ over the Perugino Pietà in the National Gallery (MPTK, p. 93). Faced with a historical fiasco, it is not surprising to find Belacqua hoping that Trinity College will endure in perpetuity. In the nooks and crannies of More Pricks Than Kicks, there lurks a sense of a catastrophic history that will equally haunt Beckett’s later work. Here, however, the catastrophe is chiefly indicated in the catastrophic inability of the present to come to any kind of significant terms with historical catastrophe. Thus Dublin is ‘the home of tragedy restored and enlarged’ (ibid.).

Belacqua is both inclined and disinclined to shrug off the culture from which he stems. This ambivalence is endemic to the book. More than anything else, Belacqua is unserious. For he inhabits a cultural no man’s land. Belacqua’s women, his marriages and affairs have the same quality of indeterminacy (or lack of determination) about them. This sexual Laodiceanism is not only a principal theme in the long unpublished predecessor to More Pricks Than Kicks, but is also precisely conveyed in (if hardly mitigated by) the archness of its title, Dream of Fair to Middling Women. In the later text, however, Belacqua’s relationships exemplify a range of choices that are sexual and cultural together: Winnie the good young Protestant bourgeoise, Lucy the Ascendancy horsewoman, Thelma one of the rising class of the Dublin petit bourgeoisie, Ruby the Irishtown working-class girl, the Smeraldina the exotic foreigner. This is partly a reflection of Beckett’s own situation during the twenties and early thirties. He fell amateurishly in love with Ethna MacCarthy, a magnetically attractive fellow student at Trinity College (later to marry his good friend Con Leventhal). He fell romantically in love with his half-Jewish cousin Peggy Sinclair, whose family had moved to Germany. Later, in Paris, he had a somewhat ambivalent if clearly not sexual relationship with Joyce’s daughter Lucia. Other women featured more or less significantly within the Beckettian psychodrama.

Beckett extracts certain features of his own early experience with women and injects them into More Pricks Than Kicks. But he also makes them Irish-focussed. He works on a principle that will repeatedly be evident in his later work: he organizes the indeterminacy of his own experience, but as indeterminacy. He abstracts Belacqua’s inchoate emotional life, but as drift. He produces a version of the long-established Irish tradition of allegorizing women. But he also treats this predominantly nationalist tradition ironically, making it serve purposes for which it was never intended, whilst expanding it, too. He makes it express, not the aspirations of what were by now the victorious classes in Ireland, but the desperations of a historically defeated and obsolescent class. The full range of the choices finally available to Belacqua matters little. The point is that ‘the forces’ in Belacqua’s mind will ‘not resolve’ (MPTK, p. 136). He makes no decisive choice. He has been deprived of any cultural foundation that might make such an act of self-definition possible. All his women are in some sense equivalent, because nothing of itself defines Belacqua in relation to them. Choice itself implodes, and Belacqua’s death arrives inconsequentially, at the random end of what is, in principle, an indefinitely extendable series.

‘These old crones, Ireland is full of them’.

In the long run, Beckett’s work was to take a quite different direction to More Pricks than Kicks. It would bear a different kind of witness to the readjustment that, from 1922 onwards, the Dublin Protestant middle classes increasingly found themselves constrained to make.24 But this is a drably clinical way of evoking a magisterially traumatized and impotent art. By and large, Beckett’s class had either exploited, patronized or ignored those subjected to a condition of ancient dispossession and deprivation. After More Pricks than Kicks, however, Beckett himself is more and more powerfully drawn towards identifying with the historical lament of the ‘other Ireland’. His childhood world was crammed with insubstantial presences, in the sense that it was full of people who didn’t count, who were not supposed to matter: the itinerant beggars, the tinkers in the back roads of Foxrock, the slummy stonecutters of nearby Glencullen. He declared of the maddened woman in his play Not I that ‘there were so many of these old crones, stumbling down the lanes, in the ditches, beside the hedgerows. Ireland is full of them’.25 His childhood had left him ‘aware of the unhappiness’ of others around him.26 He saturated his work in this unhappiness.

The Protestant middle classes had refused to assume any historical responsibility for the other Ireland. Beckett can hardly be said to assume it, either. But it nags away insidiously within his characters’ monologues and speeches. He was far too scrupulous and too subtle to imagine that any true ‘identification’ with the other Ireland was finally possible. There was therefore ‘nothing to be done’ (CDW, p. 11); nothing, that is, save accept a certain ‘obligation to express’ (DI, p. 139). True, in Beckett, expression breeds suppression. Lucky’s majestically nonsensical monologue in Waiting for Godot is so compulsive that, in the end, the other characters have violently to floor him. But the obligation to express implacably reasserts its hold. The claim of the other voice can never be stilled, because its historical condition leaves it beyond all possibility of being appropriated. It is, par excellence, ‘Not I’.

‘When it’s over, ma’am’, said the maid to de Vere White’s mother of the upheavals in Ireland in the twenties, ‘yous will be us and us will be yous’.27 As history repeatedly showed and Beckett was acutely aware, this was not to be. It is Kate’s vain hope in The Big House. She learns that ‘the gulf remain[s]’ and is absolutely unbridgeable.28 If she is to stay and commit herself to Ireland, she must do so in that knowledge. If she finds any new identity for herself, it will be partial and incomplete. Beckett’s interests are very different to Kate’s.29 But he expresses the same point as she does, perhaps above all, in Hamm’s impatient repudiations of others’ suffering in Endgame. In so far as Endgame can be thought of as alluding to Ireland – we will encounter a different way of reading it later – Hamm’s mixture of misery and callousness is a double irony directed at the hypocrisy of a class for whom, in Inglis’s phrase, the ‘other Irish’ were ‘a people to extol in conversation around a tea table, but still savages’.30 Hamm has no truck with the trivial, self-cleansing fantasy that one might atone for historical suffering by proclaiming one’s solidarity with the oppressed. For Beckett, any concept of finding a new identity for himself within Irish culture was bound to be acutely problematic. Not surprisingly, he looked elsewhere.