Beckett performed extremely well in Trinity College’s School of Modern Languages. He became Rudmose-Brown’s favourite student. Early in 1927, Rudmose-Brown suggested that he allow his name to be put forward as Trinity College’s exchange lecturer in English for the coming year at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris. In the event, the man he was supposed to replace, Thomas MacGreevy, clung on for another year, and Beckett was not in the post until November 1928. He arrived to find MacGreevy still occupying his room.

MacGreevy even contrived to stay at the École Normale for another couple of years, during which he and Beckett embarked on what would turn out to be a lifelong friendship. MacGreevy’s reluctance to be squeezed out is understandable enough. He was a poet with serious intellectual appetites and a love of modern art. In 1928 there was nowhere better to be than the rive gauche. Beckett himself quickly saw what it might offer. In Paris in Dream of Fair to Middling Women, Belacqua spends his money on ‘concerts, cinemas, cocktails, theatres, apéritifs’ (notably ‘the potent unpleasant Mandarin-Curaçao’ and ‘the ubiqitous Fernet-Branca … like a short story by Mauriac to look at’, DFMW, p. 37). Beckett behaved in a similar fashion. He also began an enduring habit of visiting art galleries. It was to his first years in Paris that he owed his growing interest in the avant-garde and his involvement in avant-garde circles. In the Paris of the late 1920s, the Surrealists were in full cry. The little magazines were going from strength to strength. These included Eugene Jolas’s transition, which was publishing Joyce’s Work in Progress. It would eventually serve as Beckett’s first publisher, notably in the case of his short story, ‘Assumption’.

That Beckett met Joyce had nothing to do with any arcane law of irresistible forces impelling two pioneering modernists towards one another. It was more a question of Irish connections. Beckett admired Joyce and his work before he got to Paris. He arrived with a letter of introduction from his uncle Harry Sinclair, who had known Joyce in Dublin. But the instrumental figure was MacGreevy. By the late 1920s, Joyce had surrounded himself with an established group of friends, amongst whom the Irish held a special place. The friends were also a support team: they put themselves at his disposal, kept him company on his outings, went on errands and performed little tasks for him. At his behest, they even looked after other friends. Above all, they worked as amanuenses and researchers for ‘Work in Progress’, reading books for Joyce and reporting back to him. With Brian Coffey and Arthur Power, MacGreevy was one of a small group of younger Irish writers and poets who were now congregating around the great man, and sometimes contributing to his project.

MacGreevy brought Beckett into Joyce’s orbit. Before very long, Beckett, too, was functioning as a kind of research assistant on the project that would eventually be known as Finnegans Wake. Indeed, Joyce obviously spotted part at least of the young man’s potential distinction, for he quickly invited him to write an essay for the volume Our Exagmination round his Factification for Incamination of Work in Progress. It turned out to be the most illuminating and arrestingly written of the twelve contributions, though it sheds light quite as much on what were to become Beckettian preoccupations as it does on Joyce’s.

Whether or not a mutual recognition of spiritual kinship was at stake, then, the relationship began very promisingly. It did not continue in the same vein. In 1928–30, Joyce’s daughter Lucia had yet to descend into the mental and psychological disarray that would so harrow her (and her family) in the 1930s. Since Beckett had become a family friend, it was logical that the two of them should be rather thrown together. Apart from meeting him in the Joyces’ apartment, she would call on him in the École Normale, and they would go out together. Since they sometimes appeared as a couple, that was what others took them for. Lucia was inclined to take them for one, too; at the very least, she clearly imagined that coupledom might be just around the corner. But Lucia was already showing signs of volatility, and Beckett’s devotion was to Joyce himself. Haplessly, clumsily, with more than a touch of what, shortly afterwards, he would call ‘the lout-ishness of learning’ (CP, p. 7), the young man disabused the daughter. The pain Lucia suffered was extreme. In a fury, Joyce barred Beckett from any further contact with himself and his family. As he discovered the full extent of Lucia’s predicament, he would gradually relent. For the moment, however, Beckett was left with the dismaying conviction that he had betrayed the trust, not just of a great modern writer, but a man he thought of as a ‘heroic being’ and fit object of reverence.1.

To focus on this ‘Left Bank Beckett’, however, is to narrate the beginnings of his French career from a familiar perspective whose very currency gives one reason to doubt it: the great modernist-to-be swiftly establishes himself within an international, cosmopolitan, avant-gardist crowd which is where, of course, he naturally belonged.2 Joyce, above all, is his passport both to international modernism and a world where, in Robert McAlmon’s phrase, everyone was busy ‘being geniuses together’.3 The piece may fit into the picture rather awkwardly: Beckett is nothing if not a melancholic modernist, and therefore something of a fringe figure, ill at ease. He haunts the milieu, rather than being at its centre. All the same, it is where he belongs. But his dislike for quite a lot of expatriate modernists, from Hemingway (as a man) to Wyndham Lewis (as a writer), is merely one of a number of aspects of Beckett that do not quite square with this conception of him. In any case, there was more than one culture on the Left Bank.

Unlike other expatriates, Beckett was to settle in Paris for good. He also immersed himself in both the language and the culture. At length, he became as much French as he was Irish. His partner and many of his closest friends were French. Beckett was not a deracinated figure in the sense that, say, Pound was, and did not lead a deracinated life in the sense that Pound did. He was a man of strong loyalties, who put down roots, if rather eccentrically. He rooted himself in Paris as other expatriates did not. In particular, at a time when he still saw himself as a university man rather than a writer, he spent two years living and working in the École Normale Supérieure.

The École Normale is quite distinct from the other great university institutions in Paris. It was born of the Revolution, on the ninth Brumaire, Year III (30 October 1794). Joseph Lakanal, one of its co-founders, announced that it was to be a source of pure and abundant light. Dominique Joseph Garat, disciple of Condorcet and its second co-founder, declared that it embodied an educational project possible ‘for the first time on earth’, to wit, ‘the regeneration of human understanding’ in a society of equals.4 According to baron and statesman Prosper de Barante, its goal was the transformation of ‘the laws of reason and intelligence’ themselves.5 In more practical terms, Garat and Lakanal also wanted it to create not only an Enlightenment-oriented intelligentsia, but a national elite and a cadre of teachers for the new republic. Heady, adventurous, chaotic, it was quickly suppressed, but Napoleon revived it. The intake of the new institution, however, was small, marked out by merit and subject to quasi-military discipline.

The ensuing history of the institution exactly captures its spirit. Its fortunes depended on political regimes. After the Restoration in 1814, it soon became suspect again, as a ‘nest of liberalism’ fomenting ‘a spirit of insubordination’,6 and was suppressed once more. With the July Revolution in 1830, it made a swift comeback, but the Second Empire distrusted it. Minister of Education Hippolyte Fortoul aimed ‘to lower [its] level of intellectual sophistication’.7 He duly presided over the collapse of philosophy into logic, the disappearance of history teaching, a reduction of library hours and the introduction of government spies in classrooms. Not surprisingly, the École Normale once more declined into relative obscurity.

By no means necessarily given to revolutionary politics – in 1848, most of them enlisted in the Garde Nationale, and opposed the revolutionary cause – the normaliens nonetheless repeatedly proved their republican credentials by turning orthodoxies on their heads and defying institutional constraints and repressive measures. Above all, they asserted the principle of intellectual independence, of what normalien Jean Giraudoux was to call ‘the particularly and passionately individual life’.8 The École Normale developed an implicit code of moral judgement which indeed sought to function as though it were in existence ‘for the first time on earth’. It was ‘normal’ proleptically, in hope. Thus, whilst not always or even frequently of the Left, normaliens were almost invariably hated by the official right. They also responded splendidly to the great French moral crises of the nineteenth century, notably in the case of Dreyfus in the 1890s.

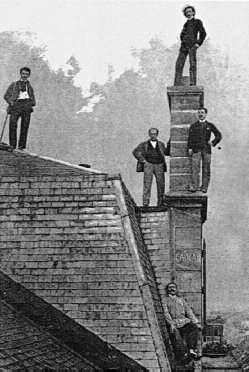

Normaliens taking to the roofs of the École Normale Supérieure, as was traditional.

The École Normale produced a series of eminent figures, from Michelet and Cousin in the 1830s to Pasteur, to Bergson and Jaurès in the 1870s, Durkheim in the 1880s and Blum and Péguy in the 1890s. The figure, however, who perhaps loomed largest at the modern École Normale was Lucien Herr, polyglot, polymath, socialist, man of deep principle and librarian extraordinaire. It was Herr who, on Dreyfus’s behalf, leapt on his bicycle to awaken the conscience of normaliens. Herr was a profound influence on the École Normale that Beckett knew, dying just two years before Beckett arrived. Another was Ernest Lavisse. Under the direction of Lavisse (1904–19), the ethos of the École Normale became one of anarchic freedom, with virtually no discipline. Normaliens of the 1920s would walk on the rooftops long into the night, go out for drinks in their pyjamas, dangle their feet in the goldfish pond and squat in three-franc cinemas on the Avenue des Gobelins watching Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd.9 Beckett captures something of the tone in the Parisian passages in Dream of Fair to Middling Women, when the Wagnerite Liebert wears plus fours to a performance of Die Walküre (only to be refused entry: ‘“Go home” they said gently, “and get out of your cyclist’s breeches”’, DFMW, p. 37). So, too, the École Normale was a magnet for idiosyncratic talent. André Maurois, René Clair and Tristan Tzara all paid visits. The emphasis, above all, was on unfettered intellectual development in its own lights and for its own sake.

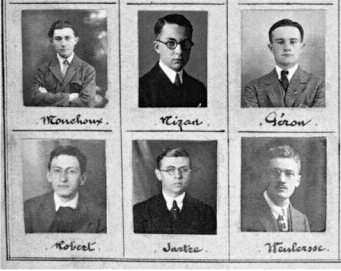

Indeed, in the 1920s, the École was a ‘brilliant and animated’ if increasingly dilapidated institution.10 Aron, Nizan, Sartre, Merleau-Ponty, Simone Weil, Lautman, Canguilhem and Cavaillès all attended during this decade. Add the names of later luminaries, and the roll-call of intellectual honour is staggering: Césaire, Lévy-Bruhl, Althusser, Foucault, Derrida, Badiou, Rancière … The list is by no means exhaustive, and dwarfs other, comparable lists. Anglophone Beckett scholars sometimes play down the importance of the École Normale in his life. The same cannot be said of normaliens, who regularly claim him as one of their own. That fact should not be slighted. Since both Francophone and Anglophone sides have their own kind of authority, the contradiction in itself tells us something very important about Beckett and his œuvre.

The products of the École Normale made much of the famous esprit normalien. They were especially proud of their humorous view of life. Normaliens positively sought out antitheses. They made a virtue of chronic (and comic) inconsistency. Before he joined the Party in 1926, for example, Paul Nizan contrived to be an arch-conservative defender of the Church, committed Communist, dandy and avant-gardist, all at the same time.11 The esprit normalien particularly manifested itself in the canular, an of ten extremely elaborate form of witty, ironical, practical joke. According to Alain Peyrefitte, it was ‘the very symbol’ of the place itself.12 Canulars could be Pantagruelian or Ubuesque. They revelled in paradox and outrageous contradiction, wresting sense from nonsense, luxury from decrepitude, intellectual wealth from poverty and filth.13 They deceived by intention. Some of the most successful ones were virtually indistinguishable from serious intellectual endeavours. Alternatively, serious concerns shaded into canulars. Bourbaki eventually became the collective signifier of a major group of mathematicians. But it was originally the name of a mysterious bearded figure who appeared in a lecture-room one day and bewildered a group of hapless first-years with an entirely spurious disquisition. At moments like this, the École Normale of the twenties seemed to be a Carrollian world where learning was scarcely separable from its naughty double, and parodic forms of intellectual discourse might actually anticipate their more serious versions.

The ‘celebrated generation of 1924’ at the École Normale Supérieure included Nizan, Péron and Sartre.

But there was also an extremely serious side to the normaliens’ self-image that was almost the reverse of canular humour, an ethical limit at which flinty inflexibility abruptly became imperative. Françoise Proust calls this the ‘granite point’.14 The ‘granite point’ was the point at which one stuck and absolutely refused to budge. It involved intellectual principle, and required demanding and even extreme forms of consistency. Herr and the Dreyfusards provided an inspiring example of this. The normaliens ‘brilliant record in the Resistance’ offers a later one.15 True, normaliens collaborated, too; the École Normale always had its right.16 Nonetheless, it was left and liberal normaliens who were chiefly responsible for its reputation. Their implacable pursuit of their causes, often to the disgrace of a more official culture, lent them enormous prestige. The Sartrian concept of engagement self-evidently belongs within this tradition.

The traditions of the canular and the ‘granite point’ had one feature in common: both were affirmations of the power and autonomy of the intellect, triumphs of the mind over ordinary circumstance. Robert Brasillach described the École Normale as an astonishing haven ‘of poetic anarchy … a fragile masterpiece of freedom’.17 When Beckett’s Murphy asserts that a factual resolution to a problem may resolve it, but ‘only in fact’ (MU, p. 101), he sounds close to the culture from which Cavaillès learnt the importance of not accepting facts, ‘for, after all, they are only facts’.18 Georges Pompidou (of all people) thought of the École Normale as offering a kingdom not of the world but of the spirit.19 In effect, the Idea came first. This would also be the case with Beckett; and if it was so in a weirdly distinctive way, then that was normalien too.

It is extremely unlikely that Beckett spent any time at the École Normale discussing phenomenology with Merleau-Ponty (though Husserl lectured in Paris in 1929).20 Nor did he engage in earnest conversations with Sartre, of a kind in which a prescient eavesdropper might have detected the first small seeds of existentialism. They would have been more likely to talk about Synge and James Stephens, whom Sartre was enthusiastically reading at the time.21 But whilst certainly rather detached, Beckett was not a solitary figure on the edge of the institution. He had two particular friends there, Georges Pelorson and Jean Beaufret, neither of whom were marginal figures, both of whom belonged to particular circles of normaliens and appear routinely in others’ memoirs. Beckett continued to see Pelorson after his time at the École. Since 1926, he had also been friends with Alfred Péron, a normalien whom he had first met at Trinity in 1926, and who first introduced him to various aspects of normalien culture. Péron had been a friend (since school) of Nizan and Sartre, who had an affair with his cousin. He was later to take on an austere and finally a sombre significance in Beckett’s life.

Beckett’s interest in continental philosophy began at the École, which is where he became a serious reader of it.22 In the Parisian section of Dream of Fair to Middling Women, Lucien quotes one of the normaliens classic points of philosophical reference, Leibniz’s account of the infinitesimal structure of matter.23 Material traces of normalien culture also flicker here and there in Beckett’s work. Lucky’s extravagantly absurd monologue in Waiting for Godot may owe a debt to canulars: figures with ropes around their necks certainly recurred in them. If ‘pseudo-couples’ throng Beckett’s works, they were also around in the École Normale. Sartre and Nizan, for example, were so close as to be popularly known as Nitre and Sarzan. Normaliens also had a special argot, and Beckett, with his gargantuan appetite for language, was no doubt aware of it. The French word ‘pot’, for example, the English form of which so exercises Beckett’s Watt, had so many different meanings at the École as to leave normaliens themselves scratching their heads. The word ‘clou’, on which the name of one of the two principal characters in Endgame is often thought to be a pun, was a key term in normalien slang. A normalien was a cloutier, meaning he wasn’t worth tuppence (‘il ne vaut pas un clou’).24 Normaliens had a particular taste for self-deprecation: this, again, was an affair of intellectual honour. The young Beckett was both temperamentally and culturally disposed to self-effacement. This disposition would later produce a writing remarkable for its extraordinarily subtle dismantlings of the ego. It was doubtless reinforced by the École.

But above all, the spirit of the canular, its irreducible, wry irony, its reverse injection of wild inventiveness, was clearly important for Beckett. Few features of his literary, philosophical and cultural experience seem closer to his intricately, bizarrely, endemically ironical cast of mind than the canular. Early in 1931, after returning from Paris, as part of the annual presentation of the Modern Languages Society at Trinity, in what was obviously a fit of nostalgia for the esprit normalien, he and Pelorson staged Le Kid, a one-act burlesque of Corneille’s Le Cid. Le Kid was ‘an intellectual “canular”’.25 Normalien playfulness, however, did not go down well everywhere in Trinity. Rudmose-Brown, in particular, was hugely infuriated.

Just a couple of months before this, Beckett had also given a paper on ‘Le Concentrisme’ to the Modern Languages Society that Ruby Cohn describes as recognizably ‘a canular normalien’ (DI, p. 10). To start with, it appears to be a casual skit on modern movements and the manifestos promoting them. It delights in surrealist extravagance and inconsequence, and pours out a stream of more or less mystifying definitions. Thus where Stendhal classically defined the novel as a mirror carried down a highway, Beckett’s Jean du Chas declares that ‘concentrism is a prism on a staircase’ (DI, p. 41). There are hints of Poundian tirade in the paper, laced with the appropriate obscurities and a dash of Eliot: ‘Under the crapulous aegis of a Cornelian valet the last trace of Dantesque rage is transformed into the spittle of a fatigued Jesuit Montaigne bears the name of Baedeker, and God wears a red waistcoat’ (DI, p. 39). The paper dismisses a vast expanse of cultural history, particularly the nineteenth century, with a negligent grandeur that also calls certain modernist self-promotions in mind.

However, the paper doesn’t really focus on Concentrism. Firstly, it is more concerned with what one might putatively call the Life and Thought of Jean du Chas and their eccentricities. Secondly, its baroque and elaborate form is not that of a manifesto. The main document appears to be composed by a third party who is addressed, in a prefatory letter, by a second party whom du Chas accosted in a bar in Marseilles, and to whom he finally left his papers. It is not clear that the addressee of the letter and the third party are in fact one person. With some justification, Cohn sees ‘Le Concentrisme’ as mocking ‘pedantry’ or learning (DI, p. 10), ‘the reduction of [du Chas’s] substance to university hiccups [hoquets universitaires]’ (DI, p. 41). But here again there are problems: the form of the piece is not that of a mock-learned essay but a biographical sketch. The presentation of the piece is not scholarly, and nor is its learning. It is, again, more Poundian than that: rich, individual, diverse, unpedantic but untidy. So, too, the presentation of the materials is modernistic: ‘Le Concentrisme’ provides us with an elegantly tiered narration, a structure of boxes within boxes with complicating points of indeterminacy, like Gide’s Les Faux-Monnayeurs. Gide is a repeated point of reference, and du Chas keeps a Gide-like journal.

There are even difficulties with thinking of ‘Le Concentrisme’ as a canular: quintessentially, the canular was a hoax. It hoodwinked people. Beckett does not appear to have seriously intended a deceit, and no-one at the Modern Languages Society was taken in.26 But a strain of the canular runs deep in the paper. Firstly, a multiplication of forms of irony was typical of the more sophisticated canulars; so, too, in ‘Le Concentrisme’, the irony turns both outward and inward. Like canulars, the piece delights in contradicting itself. The Gide to whom it might seem to pay substantial homage is casually dismissed in the middle of it. Similarly, its offhand non-sequiturs overflow any satirical purpose, expressing a pervasive indifference to logical criteria, if not despairing of them. The result is a minor instance of a form of irony that has haunted European tradition at least since Erasmus, an irony without foundations, spinning on itself like a whirligig in a void. Canular irony was like this. However much Beckett inherited from a vertiginously ironic tradition in Anglo-Irish literature supremely exemplified in Swift and Sterne, he also owed a debt to the normaliens.

There is a third example of the influence of the canular on Beckett: not long before ‘Le Concentrisme’, in June 1930, he composed a work that the paper seems quite often to echo, the poem ‘Whoroscope’. He wrote it for a competition sponsored by two figures prominent in the Parisian avant-garde, McAlmon and Nancy Cunard, and the poem effectively connected the two Left Bank cultures with which he was familiar. In effect, Beckett exploited what the École Normale was able to give him for avant-garde purposes. At first sight, ‘Whoroscope’ looks like a patently modernist piece of work. Its sports a set of endnotes, for example, purporting to explain some of its more obscure allusions, which obviously calls T. S. Eliot’s ‘The Waste Land’ to mind. Indeed, the poem itself is rather like a collection of notes, consisting largely of scraps from source-texts, if in radically attenuated form. Here Beckett’s working method appears to resemble Joyce’s, or Pound’s in the Cantos.

But this is to fit the poem into a ready-made frame. ‘Whoroscope’ won the competition. If it met with success outside the École Normale, however, the poem was very much composed within it. Matthew Feldman has recently shown that Beckett’s drew on source-texts that were either in the École Normale library, or that he borrowed from Beaufret.27 Furthermore, the subject of the poem is the life of Descartes. In other words, it addresses a philosopher of towering importance within École Normale culture. Of course, the significance of Descartes in the École Normale during the 1920s is hardly a simple matter. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century Gabriel Monod, Joseph Bédier and Gustave Lanson had achieved ‘official recognition’ for various aspects of the Cartesian tradition within the École,28 and this persisted into the 1920s. The young Sartre, for example, was an enthusiastic Cartesian.29 At the same time, however, those who espoused Cartesian tradition repeatedly collided with defenders of Pascalian sensibility and promoters of Bergsonian anti-rationalism. Nonetheless, according to Robert Smith, a Cartesian insistence on ‘the priority and independence of the mind remained the central strand’ of the École Normale’s tradition ‘throughout the Third Republic’.30 This was the case, not least, because of the work of Léon Brunschvicg, who was using Cartesianism as the foundation for a new idealism, particularly in the 1920s. Yet normaliens also treated Descartes with their customary irreverence. In Dream of Fair to Middling Women, Lucien tells stories ‘about the grouch of Descartes against Galileo’ that are ‘mostly of his own invention’ (DFMW, p. 47). Singing chansons with lyrics by Descartes was a favourite pastime. In other words, Descartes was by no means exempt from the spirit of the canular.

Feldman has superbly demolished a tradition in Beckett studies which discovered a protracted engagement with Cartesian thought in his work. He demonstrates convincingly that Beckett’s knowledge of Descartes was ‘cursory’ and that he ‘generally sought out synoptic secondary sources’.31 ‘Whoroscope’ is the one Beckett text ‘indisputably created with Cartesian sources to hand’.32 In other words, Beckett’s treatment of Descartes in the poem is precisely historical. Firstly, with ‘Le Concentrisme’, it belongs to a period when he is meditating ironically on the form of the short life (which incidentally makes both of interest to anyone trying to write one). Secondly, it positions itself in relation to a highly contested and in large part contemporary terrain.

For if Beckett’s poem draws heavily on his sources for its detail, it also radically departs from their larger theses regarding the meaning of Cartesianism. J. P. Mahaffy, no less, had written a book on Descartes, and Beckett seems to have discovered it in the École Normale library (if he did not know about it already). Whilst Mahaffy could hardly turn Descartes into a Protestant, he nonetheless placed him in the vanguard of a modernity that he also associated with Protestantism. By contrast, Adrien Baillet’s classic La vie de Monsieur Des-Cartes (1691) – much scorned by Mahaffy, but still cited today, by Rancière among others33 – presented Descartes as a good, faithful, practising Catholic. Furthermore, if Beckett read Volume 12 of Descartes’s Œuvres complètes, Charles Adam’s biography, which Lawrence Harvey took to be important for ‘Whoroscope’,34 he would have encountered a Descartes much more central to and in tune with the École Normale (and which he would have therefore been much more likely to encounter anyway): an Enlightenment man, revolutionary philosopher of progress and founder of modern science.

Beckett’s Descartes is none of these figures. On the surface of things, his irreverence towards the Mass might make him seem closest to Mahaffy’s version. But Descartes’ most beautiful lines in a notably un-beautiful poem actually evoke Dante’s God. The biggest influence on Beckett’s life of Descartes is none of his sources, but Stephen Dedalus’s life of Shakespeare in Ulysses (which it echoes). Beckett sharply demystifies Descartes, as Stephen does Shakespeare. His positions often seem wilfully heterodox, like Stephen’s. Where the standard account makes of Descartes a man, above all, of ‘powerfully linked ideas’,35 Beckett’s ‘biography’ of him is diffuse and marked by inconsequence. The poem is itself strikingly un-Cartesian, above all, in its inconsistencies. Certainly, as a recklessly un-Cartesian life of Descartes, it looks very like a canular.

However, there are further levels of irony in ‘Whoroscope’. If Baillet, Mahaffy and Adam all differ wildly in their understanding of Descartes, they also all agree on the huge significance and massive coherence of Cartesian thought. By contrast, Beckett’s emphasis falls on Descartes’s preference for omelettes made from eggs ‘hatched from eight to ten days’ (CP, p. 5). Consistency and ‘linkage’ are reduced to the level of a dottily fussy if not neurotic taste. Yet ‘Whoroscope’ is not just a reductio ad absurdum of the iron determination of the Cartesian project. ‘The shuttle of a ripening egg combs the warp of his days’, writes Beckett (ibid.): the hatching of the egg also becomes a metaphor for the development of Descartes’ work and the progress of his life. But it remains an embryonic metaphor, even an ‘abortion of a fledgling’ (CP, p. 4). The poem has its ‘granite point’. But it is a granite point of the granite point itself, a kind of degree zero of persistent will. Here as so often later, to adapt Heidegger, Beckett’s concern was with the limit of something as where its life begins.